1. Introduction

1.1 ADHD and emotional lability

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a pervasive neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 5–6% of children and 3–4% of adults [Reference Fayyad, De Graaf, Kessler, Alonso, Angermeyer, Demyttenaere, De Girolamo, Haro, Karam, Lara, Lepine, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Zaslavsky and Jin1, Reference Polanczyk, de Lima, Horta, Biederman and Rohde2]. In both children and adults ADHD is characterized by age-inappropriate and impairing levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity [Reference Faraone, Asherson, Banaschewski, Biederman, Buitelaar, Ramos-Quiroga, Rohde, Sonuga-Barke, Tannock and Franke3]. According to DSM-5 measures of emotional lability can be used in a supportive capacity to help establish the diagnosis of adult ADHD. This can include a number of symptoms such as high irritability, changing moods or low frustration threshold [Reference APA4]. Emotional lability is also a prominent feature of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder [Reference APA4], which are both common comorbidities of ADHD [Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Conners, Demler, Faraone, Greenhill, Howes and Secnik5, Reference Moukhtarian, Mintah, Moran and Asherson6]. However, it has been argued that emotional lability in adults with ADHD is not related to comorbid conditions, but is a core feature of the disorder [Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde7]. This is supported by multiple lines of evidence: emotional lability is present in adults with ADHD without psychiatric comorbidities [Reference Skirrow and Asherson8], it responds well to ADHD medication [Reference Skirrow, McLoughlin, Kuntsi and Asherson9, Reference Moukhtarian, Cooper, Vassos, Moran and Asherson10] and is related to functional impairment beyond other symptoms of ADHD [Reference Barkley and Fischer11]. Moreover, genetic studies indicate shared genes explain the strong link of ADHD to emotional lability [Reference Merwood, Chen, Rijsdijk, Skirrow, Larsson, Thapar, Kuntsi and Asherson12].

1.2 ADHD and mind wandering

Mind wandering is an omnipresent life experience, when our mind drifts away from a primary task and focuses on internal, task-unrelated thoughts and images. It has been defined as a shift of attention from the external environment towards inner, self-generated, task-unrelated and stimulus-independent thoughts, decoupled from immediate sensory perceptions [Reference Stawarczyk, Majerus, Maquet and D’Argembeau13, Reference Smallwood and Schooler14]. It is estimated that up to 50% of our daily lives are spent in a mind wandering state [Reference Kane, Brown, McVay, Silvia, Myin-Germeys and Kwapil15, Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert16]. Mind wandering can be spontaneous and unintentional, which is often detrimental to the task at hand and have little strategic value to the individual; or deliberate, when it may be related to strategic thinking about future plans [Reference Seli, Risko and Smilek17]. Excessive spontaneous mind wandering has recently been proposed as a candidate mechanism leading to the symptoms and impairments of ADHD, as it correlates strongly with ADHD symptom domains and impairment scores [Reference Seli, Smallwood, Cheyne and Smilek18–Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21], and mind wandering is closely associated with default mode network (DMN) activity [22–Reference Fox, Spreng, Ellamil, Andrews-Hanna and Christoff24] and dysregulation of the DMN is a prominent feature of ADHD [Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21]. Mind wandering and ADHD symptoms have been examined predominantly in populations of college students not diagnosed with ADHD [Reference Shaw and Giambra25, Reference Seli, Smallwood, Cheyne and Smilek18, Reference Franklin, Mrazek, Anderson, Johnston, Smallwood and Kingstone20, Reference Jonkman, Markus, Franklin and van Dalfsen26]. These studies found that spontaneous mind wandering is positively associated with ADHD symptom severity [Reference Seli, Smallwood, Cheyne and Smilek18], both when measured in the laboratory as well as in daily life [Reference Franklin, Mrazek, Anderson, Johnston, Smallwood and Kingstone20]. Participants with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD reported more task-unrelated thoughts compared with other participants [Reference Shaw and Giambra25].

1.3 ADHD and sleep quality

Poor sleep quality and the resulting sleep deprivation have profound consequences on daily human functioning, negatively affecting cognition and emotion [Reference Krause, Simon, Mander, Greer, Saletin and Goldstein-Piekarski27]. Lack of good quality sleep disrupts normal wakefulness resulting in inattention [Reference Pilcher and Huffcutt28–Reference Durmer and Dinges30]. Excessive daytime sleepiness due to disrupted sleep is extremely common in the general population [Reference Lund, Reider, Whiting and Prichard31] as well as in children and adults with ADHD [Reference Cortese, Faraone, Konofal and Lecendreux32, Reference Hvolby33]. Furthermore, adults with ADHD report higher excessive daytime sleepiness relative to healthy controls [Reference Bjorvatn, Brevik, Lundervold, Halmoy, Posserud and Instanes34]. A variety of sleep problems are associated with ADHD [Reference Konofal, Lecendreux and Cortese35]. It is estimated that up to 78% of adults with ADHD experience sleep problems [Reference Yoon, Jain and Shapiro36, Reference Kooij and Bijlenga37] and report lower sleep quality than neurotypical controls [Reference Boonstra, Kooij, Oosterlaan, Sergeant, Buitelaar and Van Someren38–Reference Surman, Adamson, Petty, Biederman, Kenealy, Levine, Mick and Faraone41]. Sleep problems are thought to add to lower quality of life in ADHD, and are also associated with poorer academic performance, obesity, as well as more negative relations with carers [Reference Um, Hong and Jeong42]. Sleep disorders may also generate ADHD-like symptoms which can make differential diagnosis challenging [Reference Oosterloo, Lammers, Overeem, de Noord and Kooij43, Reference Bioulac, Micoulaud-Franchi and Philip44]. There is a positive correlation between mind wandering and poor sleep quality or difficulty falling asleep in the general population [Reference Ottaviani and Couyoumdjian45] and a single night of sleep deprivation can increase mind wandering. Poor sleep quality as well as a range of sleep problems has also been linked to difficulties in emotion regulation and negative mood [Reference Gruber and Cassoff46–Reference Palmer and Alfano48].

1.4 Default mode network activity

The DMN consists of interconnected cortical regions, including ventromedial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, which are activated (positively correlated) during rest and deactivated (anti-correlated) in response to attentional demands [Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter49]. Individuals with ADHD have disturbed DMN connectivity leading to hyperactivation of DMN during daily activities [Reference Christakou, Murphy, Chantiluke, Cubillo, Smith, Giampietro, Daly, Ecker, Robertson, Murphy and Rubia50], which is hypothesised to lead to excessive mind wandering [Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21]. Connectivity in the DMN can also be altered by any sleep-related reduction of consciousness [Reference Horovitz, Braun, Carr, Picchioni, Balkin and Fukunaga51], such as sleep deprivation [Reference Gujar, Yoo, Hu and Walker52–Reference Dai, Liu, Zhou, Gong, Wu and Gao54]. DMN is also one of the crucial brain networks responsible for self-referential processing and emotion regulation [Reference Andrews-Hanna55–Reference Pan, Zhan, Hu, Yang, Wang, Gu, Zhong, Huang, Wu, Xie, Chen, Zhou, Huang and Wu57] and failure to downregulate the DMN activity has been linked to depressive ruminations [Reference Sheline, Barch, Price, Rundle, Vaishnavi, Snyder, Mintun, Wang, Coalson and Raichle58]. Finally, mind wandering is well-known to cause transient dysphoric mood [Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert16].

1.5 Impairment

ADHD, mind wandering and poor sleep quality are all associated with increased rates of car accidents while driving [Reference Lyznicki, Doege, Davis, Williams and A. Am Med59–Reference Yanko and Spalek62] and together with emotional lability they contribute to poor academic performance [Reference Doi, Minowa and Tango63, Reference Barkley and Fischer11, Reference Dewald, Meijer, Oort, Kerkhof and Bogels64, Reference Smallwood and Schooler14]. Emotional lability leads to multiple functional impairments 0 [Reference Barkley and Fischer11].

1.6 Aim and hypotheses

In summary, it is striking that ADHD, excessive mind wandering, poor sleep quality and emotional lability bear such a close resemblance in their negative effects on everyday functioning and share a close association with disrupted activity within the DMN. Despite this, these concepts have never been investigated together. Therefore, in the present study we aim to investigate the effect of mind wandering, emotional lability and sleep quality on the severity of symptoms of ADHD in a sample of adults diagnosed with ADHD. Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesize that all three variables will significantly exacerbate the symptomatology of ADHD. We further hypothesize that the independent variables will be causally linked: 1) mind wandering will lead to emotional lability [Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert16] which would lead to ADHD symptom severity [Reference Skirrow, McLoughlin, Kuntsi and Asherson9, Reference Barkley and Fischer11, Reference Skirrow and Asherson8, Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde7]; and 2) poor sleep quality would lead to emotional lability [Reference Gruber and Cassoff46–Reference Palmer and Alfano48] and mind wandering [Reference Carciofo, Du, Song and Zhang65, Reference Poh, Chong and Chee66], which would lead to ADHD symptom severity [Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde7, Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21].

2. Methods

2.1 Sample

The data presented here is part of a larger study (Oils and Cognitive Effects in Adult ADHD Neurodevelopment, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01750307). In total 81 English-speaking adults with ADHD volunteered to participate in the study (60 male, 51 female, mean age 32.4 years, SD 10 years, mean IQ 110, SD 13). Diagnosis was made according to the DMS-5 criteria [Reference APA4]. Participants were recruited via South London and Maudsley Adult ADHD Outpatient Services (see Table 1 for detailed characteristics).

Table 1 Background, clinical and cognitive variables of the study sample.

Note. MEWS: Mind Excessively Wandering Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ALS: Affective Lability Scale; CAARS: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales.

2.2 Clinical measures

ADHD symptoms were measured using the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) [Reference Conners, Erhardt and Sparrow68], a self-report 18-item scale assessing the level of inattention and hyperactivity/ impulsivity consistent with the DSM-5 criteria for adult ADHD [Reference APA4]. Emotional Lability was measured with the Affective Lability Scale (ALS) [Reference Oliver and Simons69] a self-report 18-item scale sensitive to swift changes in emotion and mood.

Mind wandering was measured with the Mind Excessively Wandering Scale (MEWS) [Reference Mowlem, Skirrow, Reid, Maltezos, Nijjar, Merwood, Barker, Cooper, Kuntsi and Asherson19], a reliable self-report 12-item questionnaire developed on the basis of ADHD patients’ descriptions of their thought processes: capturing thoughts constantly on the go, thoughts flitting from one topic to another and multiple overlapping thoughts at the same time. The MEWS is thought to be especially sensitive in detecting unintentional and uncontrollable mind wandering that is closely related to ADHD [Reference Mowlem, Skirrow, Reid, Maltezos, Nijjar, Merwood, Barker, Cooper, Kuntsi and Asherson19, Reference Seli, Risko and Smilek17, Reference Jonkman, Markus, Franklin and van Dalfsen26]. MEWS has been validated against experience sampling data in daily life (Moukhtarian et al., unpublished data), and was significantly correlated with measures of spontaneous but not deliberate mind wandering in a community sample (Mowlem et al., unpublished data).

Sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer70], a 19-item questionnaire with high validity and reliability in retrospective self-assessment of disturbed sleep quality over the last month, including the ensuing daytime dysfunction [Reference Carpenter and Andrykowski71]. PSQI broadly assess both quantitative (sleep latency, number of awakenings) and qualitative (restlessness, functioning) aspects of sleep and its utility is established in both clinical and non-clinical populations [Reference Mollayeva, Thurairajah, Burton, Mollayeva, Shapiro and Colantonio72]. PSQI covers several indications for sleep disorders using the following seven component scores: 1) subjective sleep quality; 2) sleep latency; 3) sleep duration; 4) habitual sleep efficiency; 5) sleep disturbances; 6) use of sleeping medication; 7) daytime dysfunction [Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer70]. People with ADHD who additionally suffer from sleep problems show difficulties across all these seven components [Reference Mulraney, Sciberras and Lecendreux73].

2.3 Statistical analyses

We conducted serial multiple mediation modelling using ordinary least squares path analysis in PROCESS [Reference Hayes74]. For the estimation of the indirect effects of the independent variables on the outcome variable via the intermediary variables we used 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) based on 10,000 bootstrapping samples. A confidence interval was considered statistically significant when it was entirely above or below zero. The two-tailed alpha was set at 0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

A multiple regression was run to predict ADHD symptom severity from mind wandering, sleep quality and emotional lability. There was linearity as assessed by partial regression plots and a plot of studentized residuals against the predicted values. There was independence of residuals, as assessed by a Durbin-Watson statistic of 1.970. There was homoscedasticity, as assessed by visual inspection of a plot of studentized residuals versus unstandardized predicted values. There was no evidence of multicollinearity, as assessed by tolerance values greater than 0.1. The assumption of normality was met, as assessed by a Q-Q Plot.

The multiple regression model statistically significantly predicted ADHD symptom severity, F(3, 74) = 86.969, p <.001. R2 for the overall model was 77.9% with an adjusted R2 of 77.0%, a large effect size according to Cohen (1988). Mind wandering and emotional lability added statistically significantly to the prediction, p <.05. Regression coefficients and standard errors are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis.

Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SEB = Standard error of the coefficient; β = Standardized coefficient.

All study variables were significantly positively correlated, see Table 3.

Table 3 Summary of Correlations.

Note. MEWS: Mind Excessively Wandering Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ALS: Affective Lability Scale; CAARS: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales. All correlations are statistically significant at the level 0.001, two-tailed.

As mediators in model A (emotional lability and sleep quality) were significantly correlated, r(78) = 0.377, p < 0.001) as well as in model B (mind wandering and emotional lability), r(78) = 0.575, p < 0.001 we run a serial multiple mediation models (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A) Serial multiple mediation model of sleep quality and emotional liability on the effect of mind wandering on ADHD symptom severity; B) Serial multiple mediation model of mind wandering and emotional liability on the effect of sleep quality on ADHD symptom severity.

Note. MEWS: Mind Excessively Wandering Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ALS: Affective Lability Scale; CAARS: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales.

3.1 Model A

The model (see Table 4) was statistically significant, R = 0.65, R2 = 0.42, F(1,76) = 54.84, p < 0.001. We found a significant direct effect of mind wandering on ADHD symptom severity (c’ = 0.42, p = 0.003). There was a strong association between mind wandering and emotional lability (a2 = 0.46, p < 0.001) as well as between mind wandering and sleep quality (a1 = 0.33, p = 0.000). We found a significant effect of emotional lability on ADHD symptom severity (b2 = 1.61, p < 0.001), but no effect of sleep quality on ADHD symptom severity (b1 = 0.07, p = 0.634). The effect of mind wandering on ADHD symptom severity was mediated by emotional lability (Ind3 = 0.74, 95% CI 0.49–1.04), but not sleep quality (Ind1 = 0.02, 95% CI: -0.07 to 0.13). However, the interaction between the mediators also yielded a statistically significant mediatory effect where sleep quality affected emotional lability (Ind2 = 0.10, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.25).

Table 4 Results from the serial multiple mediation model of the intermediary effect of sleep quality and emotional lability on the relationship between mind wandering and ADHD symptom severity.

Note. MEWS: Mind Excessively Wandering Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ALS: Affective Lability Scale; CAARS: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales; CI: 95% Bootstrapping Confidence Intervals.

c’: direct effect of the independent variable (Emotional Liability in A or Sleep Quality in B) on the outcome variable (ADHD Symptom Severity);

a: effect of the independent variable on the intermediary variable (Emotional Liability in A or Sleep Quality in. B);

b: effect of the intermediary variable on the outcome variable; c: total effect, which is the sum of the direct and indirect effects;

d: serial effect of mediator 1 (Sleep Quality) on mediator 2 (Emotional Lability);

Ind: indirect effect of the independent variable on the outcome variable via the intermediary variables;

Ind1: MEWS ---> PSQI ---> CAARS.

Ind2: MEWS ---> PSQI ---> ALS ---> CAARS.

Ind3: MEWS ---> ALS ---> CAARS.

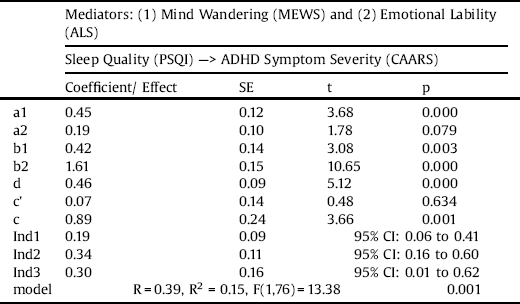

3.2 Model B

The model (see Table 5) was statistically significant, R = 0.39, R2 = 0.15, F(1,76) = 13.38, p = 0.001. There was no statistically significant direct effect of sleep quality on ADHD symptom severity (c’ = 0.07, p = 0.634). There was a strong effect of sleep quality on mind wandering (a1 = 0.45, p < 0.001), but no significant effect of sleep quality on emotional lability (a2 = 0.19, p = 0.079). Again, we found a significant effect of mind wandering on ADHD symptom severity (b1 = 0.42, p = 0.003), as well as emotional lability on ADHD symptom severity (b2 = 1.61, p < 0.001). As there was no significant direct effect, the influence of sleep quality on ADHD symptom severity was completely mediated by mind wandering (Ind1 = 0.19, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.41) and emotional lability (Ind3 = 0.30, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.62). The interaction between the mediators was also statistically significant (Ind2 = 0.34, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.60).

Table 5 Results from the serial multiple mediation model of the intermediary effect of mind wandering and emotional lability on the relationship between sleep quality and ADHD symptom severity.

Note. MEWS: Mind Excessively Wandering Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ALS: Affective Lability Scale; CAARS: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales; CI: 95% Bootstrapping Confidence Intervals.

c’: direct effect of the independent variable (Emotional Liability in A or Sleep Quality in B) on the outcome variable (ADHD Symptom Severity);

a: effect of the independent variable on the intermediary variable (Emotional Liability in A or Sleep Quality in. B);

b: effect of the intermediary variable on the outcome variable;

c: total effect, which is the sum of the direct and indirect effects;

d: serial effect of mediator 1 (Sleep Quality) on mediator 2 (Emotional Lability);

Ind: indirect effect of the independent variable on the outcome variable via the intermediary variables;

Ind1: PSQI ---> MEWS ---> CAARS.

Ind2: PSQI ---> MEWS ---> ALS ---> CAARS.

Ind3: PSQI ---> ALS ---> CAARS.

4. Discussion

We found that mind wandering and emotional lability predicted ADHD symptom severity and that mind wandering, emotional lability and sleep quality are all linked and significantly contribute to the symptomatology of adult ADHD. The mediation models supported both our prior hypotheses. Mind wandering was found to lead to emotional lability which in turn leads to ADHD symptom severity; and poor sleep quality was found to exacerbate mind wandering leading to ADHD symptoms.

Our findings fit well into the previous findings. We confirmed that mind wandering and emotional lability are significantly linked with core deficits in adult ADHD [Reference Skirrow, McLoughlin, Kuntsi and Asherson9, Reference Barkley and Fischer11, Reference Skirrow and Asherson8, Reference Seli, Smallwood, Cheyne and Smilek18, Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde7, Reference Mowlem, Skirrow, Reid, Maltezos, Nijjar, Merwood, Barker, Cooper, Kuntsi and Asherson19, Reference Franklin, Mrazek, Anderson, Johnston, Smallwood and Kingstone20, Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21] and that poor sleep quality may lead to emotional dysregulation [Reference Gruber and Cassoff46–Reference Palmer and Alfano48] as well as exacerbate mind wandering [Reference Carciofo, Du, Song and Zhang65, Reference Poh, Chong and Chee66]. We have also confirmed an influential result that mind wandering could lead to emotional lability and negative emotions [Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert16].

4.1 Limitations

It should be noted, that even though we would like to hypothesise that the links between the variables are causal and despite the fact that the mediation model itself encourages a causal interpretation of the links between the variables [Reference Hayes74], the cross-sectional nature of our data limits the causal inferences that can be drawn from these analyses [Reference Winer, Cervone, Bryant, McKinney, Liu and Nadorff75]. Therefore, we based our model on a specific a priori hypothesis developed based on a theoretical model that arises from empirical observations linking the constructs investigated here [Reference Axelrod, Rees, Lavidor and Bar76, Reference Gallo and Posner77]. To investigate the causal nature of these hypotheses, further studies using a longitudinal design or experimental manipulations will be required.

4.2 Mind wandering and emotional lability

In this study, we have investigated a specific hypothesis that mind wandering leads to emotional lability. This is based on one of the most influential studies in the field, investigating mind wandering in a neurotypical group, where it has been found that mind wandering was the cause, and not a consequence, of negative feelings [Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert16]. However, another prominent study found that negative mood can lead to more mind wandering [Reference Smallwood, Fitzgerald, Miles and Phillips78] and today it is generally acknowledged that emotional processes play a major, if not the central, role in generation of mental content during mind wandering [Reference Smallwood and Schooler14]. It seems that mind wandering and emotional lability are so closely linked that a two-way process might be a best explanation for the existing data. Mind wandering is a cause of emotional dysregulation when the negative content of the thought, or the intrusive nature of mind wandering itself, leads to higher levels of stress, including emotional distress, which in turn enhances the level of task-unrelated, negatively-valanced thoughts. Such a mechanism seems to be especially plausible in adults with ADHD, as the mind wandering experiences in ADHD are more intrusive and excessive [Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21], and there is emotional overactivity to stressful events [Reference Skirrow and Asherson8]. Mind wandering and emotional lability in adults with ADHD are both an integral part of the disorder [Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde7], and this may be underpinned by abnormal activity in the DMN [Reference Shaw, Stringaris, Nigg and Leibenluft79, Reference Bozhilova, Michelini, Kuntsi and Asherson21]. This reasoning can be additionally supported by the fact that mindfulness-based treatments for adults with ADHD seem to be promising and the preliminary data suggest high efficacy [Reference Cairncross and Miller80]. Mindfulness and meditation practices are known to normalize activity and connectivity in the DMN and lead to decreased mind wandering and improved emotion regulation [Reference Mitchell, Zylowska and Kollins81]. Further work is however needed to test the hypotheses arising from our study.

4.3 Sleep, emotional lability and mind wandering

We found a similar bi-directional relationship between sleep quality and mind wandering, which is in line with previous findings in neurotypical subjects [Reference Carciofo, Du, Song and Zhang65]. It seems that not only poor sleep quality and the resulting sleep deprivation leads to higher incidence of mind wandering [Reference Poh, Chong and Chee66], but also a restless wandering mind makes it harder to fall asleep. It should be noted that one of the items on the MEWS scale, which was used to measure mind wandering in our study, reads: “Because my mind is ‘on the go’ at bedtime, I have difficulty falling off to sleep” [Reference Mowlem, Skirrow, Reid, Maltezos, Nijjar, Merwood, Barker, Cooper, Kuntsi and Asherson19]. Mind wandering and sleepiness are similar in terms of the EEG signal and are both linked to the DMN activity [Reference Braboszcz and Delorme82]. Moreover, poor sleep quality results in negative affect [Reference Carciofo, Du, Song and Zhang65], which is also in line with our findings regarding sleep quality and emotional lability. As discussed above, because mind wandering and emotional lability are so closely linked via negative affect, even when poor sleep quality exacerbates one of the variables, inevitably both of them will be increased [Reference McVay, Kane and Kwapil83, Reference Ottaviani and Couyoumdjian45], especially in adults suffering from ADHD.

4.4 Future directions

In summary, this study aimed to link the currently mostly independently investigated concepts of emotional lability, mind wandering, sleep quality and adult ADHD. Future studies should employ experimental on-task measures of mind wandering (experience sampling), sleepiness (event-related potentials, quantitative electroencephalography and polysomnography) and frustration tasks to objectively measure emotional lability; and link them to the activity of the DMN using neuroimaging and experimental designs involving ADHD medication and mindfulness training. Investigating these concepts in diverse samples, across developmental stages and diagnostic categories, holds a big promise in fully uncovering the causal mechanism behind these impairing deficits.

Declaration of interest

Professor Asherson has received funds for consultancy on behalf of King's College London to Shire, Eli-Lilly, and Novartis, regarding the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD; educational/research awards from Shire, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Vifor Pharma, GW Pharma, and QbTech; speaker at sponsored events for Shire, EliLilly, and Novartis. All funds are used for studies of ADHD. Ruth Cooper has received funding from Vifor Pharma. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank The National Adult ADHD Clinic at the South London and Maudsley Hospital (SLaM) and all study participants. The OCEAN study was funded by Vifor Pharma (PADWUDB), awarded to Philip Asherson with King’s College London as sponsor. Bartosz Helfer is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 643051. Professor Asherson is supported by NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health, NIHR/MRC (14/23/17), Action Medical Research (GN 2315) and European Union (643051, 602805 and 667303). This study reflects the authors’ views and none of the funders holds any responsibility for the information provided.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.