Introduction

At the turn of the 21st century the concept of ‘new social risks’ became a focus of welfare state literature. First elaborated by Taylor-Gooby and co-authors (Reference Taylor-Gooby2004), Bonoli (Reference Bonoli2005; Reference Bonoli, Armingeon and Bonoli2006) and Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1999; Reference Esping-Andersen2005), the concept was based on the claim that mature welfare states, designed to meet the social needs and risks of the industrial era, had become ineffective in the face of recent economic and social shifts, as well as long-term structural trends that were affecting labour market, demographic and other socio-economic structures. Proponents of the ‘new social risks’ perspective argued that the transition to post-industrial, knowledge-based globalised economies had undermined stability of labour markets, producing unemployment and precarity. Fertility was declining, societies were ageing, and families were becoming less stable, less able or willing to provide care for young children and the burgeoning numbers of older people. Large, new and unintegrated immigrant populations were entering welfare states that were already dealing with austerity. The old social risks of the industrial era (periods of unemployment, retirement) had been predictable and could largely be managed on Bismarckian insurance principles. New risks, by contrast, affected societies and life stages that had not traditionally presented risk. By the early 2000s new social risks were recognised as shared major challenges to mature welfare states.

Studies of new social risks focused first on the older European Union (EU) states (EU15) (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2005; Armingeon and Bonoli, Reference Armingeon and Bonoli2006; Kitschelt and Rehm, Reference Kitschelt, Rehm, Armingeon and Bonoli2006) but soon extended to include the EU8 Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) states that joined the EU in 2004 (EU8) (Cerami, Reference Cerami2006, Reference Cerami2008, Reference Cerami and Palier2010; Kuitto, Reference Kuitto2016). Our State of the Art article (SOTA) brings Russia into the dialogue on ‘new social risks.’ Since 2000, Russia has also experienced destabilised labour markets, declining fertility and population ageing, social security crises and large-scale international labour immigration. Whilst the history and current regime in Russia differ greatly from those further West, all confront a set of broadly-shared new challenges to sustainability of their welfare states. The purpose of this article and themed section is to show the sources and the extent of shared new risks across the cases. We explain how different welfare and political legacies produce convergence and divergence in governments’ responses to three major policy challenges: pension system reforms, demographic (pro-natalist and family) policies, and integration of immigrants.

Defining the welfare state

Whilst we acknowledge the long tradition of debate around the term ‘welfare state’ (Briggs, Reference Briggs1961; Titmuss, Reference Titmuss1963; Offe, Reference Offe1984; Clarke, Reference Clarke and Sandermann2014; Garland, Reference Garland2021), we consider it useful to provide a working definition that applies across the cases covered in our themed section, in order to highlight selected comparative aspects. We define the ‘welfare state’ as an established and authorised collectivity or network of political and governing institutions that provides or facilitates the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of citizens of a bounded territorial unit, typically a nation state. We focus on those goods and services that are provided in the public sector, i.e. administered by national states or sub-national levels of government. These typically include public education, health care, social insurance, transfer payments (social benefits), public housing sectors, and other partly or fully subsidised social goods and services (Hill, Reference Hill1996; Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Welfare services and programmes are funded by public budgets or state-mandated schemes such as contributory social insurance, rather than privately-funded, though the distinction is not always clear. Welfare states may be more or less inclusive, generous, redistributive or status-maintaining with governments playing larger or smaller roles (George, Reference George, George and Taylor-Gooby1996; Gough, Reference Gough, Dani and de Haan2008; Muñoz de Bustillo, Reference Muñoz de Bustillo2019).

The ’golden age’ of the welfare state: West and East

The Russian, EU8 and EU15 polities that are compared in this themed section all feature mature welfare states that followed a post-WWII trajectory of expansion and contraction. They experienced a ‘Golden Age’ from the 1950s and through the 1970s, when governments increased welfare expenditures (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1996; Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Social payments and protections were extended to citizens throughout the life cycle, from maternity and child benefits to disability and pension insurance (Haggard and Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008). Both living and welfare standards were much higher in the West and social provision much poorer and more basic in the East, but both EU15 and communist states created broadly-inclusive welfare systems. Systems were characterised by nearly full employment for men in all cases as well as most women in the communist states. ‘Standard’ employment, i.e. full-time, long-term jobs that provided a living wage and social insurance, was the norm across the cases. Social security, including pension systems, were funded by workers’ and employers’ contributions over decades of employment. In the EU15 states, a ‘male breadwinner’ model dominated; the majority of women were not in the labour force (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Fink, Clarke, Fink, Lewis and Clarke2001). Levels of women’s employment were much higher in communist states, typically more than 70 per cent, producing ‘dual-earner’ systems that imposed a ‘double burden’ of both employment and home/care work for mothers, though governments provided more public childcare.

From the 1980s, welfare throughout the region deteriorated under structural and financial pressures. In the EU15, economic growth slowed, energy prices increased, and the 1998 and 2008 financial crises shocked government budgets and produced welfare retrenchment and austerity. The collapse of communism in 1989 led to deep transitional recessions and radical cuts in welfare states. Post-communist governments cut back welfare provision, progressively withdrawing from post-war commitments to redistribution and social protection. These trends deepened with the 1998 and 2008 financial crises and ensuing austerity policies. While both EU15 and communist welfare states contracted, the deep post-communist economic crises further widened the gap between West and East (Deacon, Reference Deacon2000; Korpi, Reference Korpi2003; Kivinen and Li, Reference Kivinen, Li and Pursiainen2012). In comparison with the post-war decades, both sets of welfare states faced what Paul Pierson (Reference Pierson2001) called ‘permanent austerity’.

Though their trajectories were broadly similar, the political sources and contexts of EU15 and communist welfare states were fundamentally different. Under Europe’s post-WWII ‘class compromise,’ benefits of economic growth were distributed broadly through tripartite or corporatist bargaining structures, which were shaped in turn by competitive elections and democratic demand-making. Elites responded to citizens’ felt needs and policy preferences; citizens were legally entitled to services and programmes for which they qualified. Communist welfare states, by contrast, were created top-down by authoritarian elites and shaped by the priorities of the state. Welfare provision played a legitimising role for communist governments as part of a tacit ‘social contract’. The contract allowed communist leaders to buy political quiescence with limited use of state violence in the late communist decades (Cook, Reference Cook1993; Ghodsee and Orenstein, Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021). But welfare was not an entitlement as in the West. Rather it was provided contingent on compliance. Communist governments assumed rights to require that their citizens’ behaviour comply with the orthodoxies and needs of the state, by coercion if necessary. The legacies of these political differences would affect governments’ responses to new social risks.

Shared new social risks and policy challenges

By 2000 the set of new social risks identified above – destabilised labour markets, population ageing, unsustainable social security systems – were shared to varying degrees by all states of the EU15, EU8 and Russia. The EU8 and Russia lagged the EU15 by about a decade in labour market destabilisation and declining birth rates, but confronted similar problems. Large-scale, uncontrolled immigration also emerged as a risk to welfare states in the EU15 and Russia after 2000. Since WWII international labour migration had been largely controlled by governments, and flows of asylum seekers remained modest and stable until the 1990s. By 2000 both were growing steadily. There was large-scale labour immigration to Russia during the 2000s and large-scale immigration of both asylum seekers/refugees and labour migrants to Europe after 2010. Russian and EU15 governments were faced with the challenge of managing and integrating hundreds of thousands of migrants of different backgrounds. The problems created by these shared new risks – growing labour precarity, pension system crises, below-replacement fertility, and large immigrant populations presenting integration challenges – were recognised as major policy issues by all governments and stood at the top of welfare policy agendas. (The EU8 largely controlled and limited international immigration until 2022, when they, along with the rest of the EU states, voluntarily accepted refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in numbers exceeding any previous post-WWII migration into Europe.)

Destabilised labour markets

By 2014, the full-time long-term jobs with contributory social security benefits that had been dominant for post-war generations gave way to insecure and precarious forms of employment for growing numbers of workers, especially women and young people entering labour forces (Ciccia and Sainsbury, Reference Ciccia and Sainsbury2018). Labour markets were de-regulated by a combination of global competition and liberalising government policies. A large literature analyses changes in labour markets in Europe and Russia since the 1980s, documenting growth of non-standard work (i.e. part-time, temporary and self-employment) (ILO, 2016; Matsaganis et al., Reference Matsaganis, Özdemir, Ward and Zavakou2016; Schmid and Wagner, Reference Schmid and Wagner2017; Agarwala, Reference Agarwala2018; European Commission, 2018). By 2014, slightly above 40 per cent of those employed in EU states were in non-standard employment and all categories (i.e. short-term, part-time, self-employment) had increased significantly since the 1980s (Matsaganis et al., Reference Matsaganis, Özdemir, Ward and Zavakou2016: 10; Eurofound, 2018). In Russia the proportion of non-standard workers was lower, approximately 15 per cent, but the level of yet more insecure informal employment stood at an estimated 20 per cent. Guy Standing (Reference Standing2016) termed these workers a new ‘precariat’. Labour scholars described a shift to ‘dual’ labour markets featuring full-time, securely employed and insured workers on the one hand, and part-time, precariously-employed and un- or under-insured workers on the other. The second group experienced higher rates of unemployment, insecurity and poverty. Many failed to qualify for labour pensions, disability and other forms of social insurance, leaving them disconnected from established social security mechanisms as either contributors or recipients, shrinking both insurance funds’ contributions and coverage. Governments were faced with growing risks of social insecurity, working poor and destitute retirees.

Declining fertility and ageing populations

Concern about negative demographic trends and their implications for welfare states also emerged as a prominent issue across the cases. EU15 fertility rates began to decline in the mid-1960s, fell below replacement levels (2.1 children per woman) in the following decade, and have remained slightly above 1.5 to the present (see Figure 1). Decline has been driven partly by women entering labour forces in larger numbers. In CEE (EU8) states and Russia, fertility fell later but more sharply and has remained below EU15 levels for most of the period under study (Figure 1). As birth rates fell, life expectancy was in many cases increasing in EU15 and EU8 states (Kazimov and Zakharov, Reference Kazimov, Zakharov, Goerres and Vanhuysse2021; Vanhuysse and Perek-Bialas, Reference Vanhuysse, Perek-Bialas, Goerres and Vanhuysse2021). In Russia, by contrast, life expectancy fell in the post-transition years because of comparatively high rates of alcohol consumption and other factors (Titterton, Reference Titterton2006). Mass blood-borne virus and sexually transmitted infections, driven by adverse risk behaviours such as illicit drug use, exacerbated morbidity and mortality, challenging governments and public health officials (Titterton, Reference Titterton2006). Most governments in all three regions faced persistently low birth rates.

Figure 1. Fertility rates (%) in EU15, CEE and Russia 1960-2021.

Source. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022).

Note. EU-15 refers to Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom. CEE countries are Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

Together the impacts of these labour market and demographic trends undermined financing of social security systems. With societies ageing, birth cohorts and labour forces shrinking, pension funds’ obligations grew as contributions declined. In the regions’ mostly pay-as-you-go pension systems, current workers’ contributions were used to pay current pensioners. Ratios between contributors to pension funds and recipients were worsening to varying degrees across the cases. As Figure 2 shows, the old age dependency ratio increased steadily and in parallel across the EU15, EU8 and Russia, from 14.8 per cent in 1960 to 33 per cent in 2021 in the EU15, 11.3 per cent to 30.7 per cent in the EU8, and 9.6 per cent to 24.4 per cent in Russia. Growth of non-standard employment exacerbated deficits, depressing levels of contributions into pension and other social insurance funds by those in the labour force. Governments faced new risks of pension financing crises and declining pension payments. In the view of the World Bank, by the early 1990s mature industrial states were experiencing a shared ‘Old Age Crisis’ (World Bank, 1994).

Figure 2. Old Age dependency ratio, (ratio of those ages sixty-four plus to working population ages fifteen to sixty-four) in EU, CEE and Russia, 1960-2020.

Source. World Bank (2019).

Note. Old Age dependency ratio, (old as % of working-age population) – is the ratio of older dependents – people older than sixty-four – to the working-age population – those ages fifteen to sixty-four. Data are shown as the proportion of dependents per 100 working-age population.

International immigration

Immigration of international labour migrants and asylum seekers constituted the third major ‘new risk’ for EU15 and Russian welfare states. The first decades of the 21st century brought to Europe and Russia labour and refugee migrations on a very large scale, exceeding any since WWII. In Russia, where international migration had been held to very low levels during most of the communist period, the transition opened borders and immigration ballooned after 2000. Large-scale labour migration from Central Asia to Russia began in the early 2000s, spurred by the rapid take-off of Russia’s economy while economic decline continued in most of the post-Soviet Central Asian periphery (Schenk, Reference Schenk2018). By 2010, Russia had become ‘the center of a regional migration system encompassing the countries of the former Soviet Union, second in global importance only to the migration system centered on the United States and encompassing Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean’ (Light, Reference Light2016: 51). It is difficult to estimate the overall numbers in Russia because many were circular or seasonal migrants, but the scale of entries grew to several million by 2007 (Schenk, Reference Schenk2018). Immigration was uncontrolled because of Russia’s visa-free regime with the former Soviet states. Most migrants remained and worked in Russia without registration or legal status.

In the EU15 the post-war era of controlled, largely legal labour immigration, often from former colonies, and migrants’ integration into most welfare states had ended by the 1990s (Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury2012). Beginning with the Yugoslav Wars, the modest numbers of asylum seekers who had arrived through the post-war decades increased dramatically. After 2010, hundreds of thousands fleeing war and repression in Syria, Iraq, Libya and other Middle-East and North African (MENA) states came annually, peaking at a million in 2015, much of it irregular and uncontrolled. Most irregular migrants came across the Mediterranean and initially concentrated in Greece and Italy, but eventually dispersed through most of the EU15, with Germany accepting the largest number. As of this writing thousands continue to arrive every month. A minority have been granted asylum under the Geneva Convention; larger numbers hold one of several subsidiary temporary protected statuses; many remain unregistered and largely unintegrated. Immigration has been a major and contentious issue in the majority of EU15 elections since 2015, fuelling the rise of populist challenges to mainstream governing political parties. It has also been a major issue in Russia’s national and regional politics (Cook, Reference Cook2022).

Convergent and divergent responses to new social risks

Confronting shared new social risks in an era of austerity, governments have often responded with policies of liberalisation, privatisation and social exclusion. Similarities in the nature and timing of challenges faced by mature EU15, EU8 and Russian welfare states have pushed them in broadly similar policy directions – toward deregulating labour markets, privatising social security, and withdrawing the state from sectors of the social sphere (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen and Palier2010: 12). Additional factors reinforce the waves of welfare retrenchment. Ideological influences contributed to this, including the ‘hegemony of liberalism’ and market fundamentalism, especially in the transitioning states of CEE and Russia after communism’s collapse (Lendvai and Stubbs, Reference Lendvai and Stubbs2015; Ghodsee and Orenstein, Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021). Institutional and political factors also played some role. In the EU15, and after 2004 the EU8, Brussels promoted retrenchment through caps on member states’ budget deficits and promotion of austerity. EU institutions arguably created a ‘democratic deficit’ that limited political elites’ accountability to electorates, constrained electoral pressures to maintain welfare programmes and enabled greater influence of monetarist ideologies among established parties across the political spectrum (Sissenich, Reference Sissenich2007). The influence of the World Bank and other International Financial Institutions (IFIs) promoting liberal welfare policy was also strong in this period.

The degree of convergence and divergence has, however, varied across policy areas. We find much similarity in privatising social security reforms across the cases. In pro-natalist and family policies, some states have turned away from liberalisation to increase state interventions and expenditures. Here we find great divergence between EU15 states on the one hand, and post-communist states on the other. While both sets of governments have sought to raise birth rates, EU15 policies have relied on incentives that promoted work-family reconciliation and increased gender equality. Post-communist states, by contrast, have supplemented pro-natalist incentives with increased restrictions on women’s reproductive rights and relied on nationalist, neo-familialist ideological pressures intended to re-traditionalise women’s roles. Policies toward immigration present a mixed picture, with both Russia and EU states relying to different degrees on integration, social exclusion, and coercion in efforts to control migrant inflows.

Below we discuss reforms in the three major areas mapped above: policies to address crises of social security systems; pro-natalist and family policies; and policies toward international migrants and refugees.

Reforming social security systems: convergent policies

Pension reforms provide the most striking example of policy convergence across the cases. According to Taylor-Gooby (Reference Taylor-Gooby2004) citing an OECD (2000: 46) report, ‘strengthening of private pensions is the most important trend in the current reform of pension systems’. Initiatives to establish mandatory private (individual) invested pension tiers were legislated in Russia, Poland, Hungary, Great Britain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Bulgaria, the Baltic States and others (Sokhey, Reference Sokhey2020). Such partial privatisation was supposed to reduce governments’ responsibilities for providing social security, the single most expensive welfare programme, relieve current workers from the need to fully finance current pensions, and increase the size and adequacy of retirement benefits through market earnings (Muller, Reference Muller2004). Here analysts stressed external influences, particularly the World Bank, as the key actor leading a broader ‘transnational advocacy coalition’. The Bank’s touchstone publication Averting the Old Age Crisis (World Bank, 1994) promoted partial privatisation as the solution to pension fund viability problems (World Bank, 1994; Orenstein, Reference Orenstein2008). Specifics of the reform – its pace, size of the private tier, state regulation of its investment – varied from case to case, but the broad parameters as well as flaws of the model were shared (Sokhey, Reference Sokhey2020). Comparative study showed how the mechanism for financing transition to a private tier broke down in several cases, including Russia, Poland, Hungary and Great Britain, under severe financial stress of the 2008 financial crisis. Governments responded by declaring moratoriums on privatisation, raiding private tiers to pay current pensions, and in several cases abandoning or scaling back pension reform (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Aasland and Prisyazhnyuk2019). Heneghan (Reference Heneghan2022) has claimed to detect paradigmatic change in World Bank pension programme policy since the publication of Averting The Old Age Crisis. While we are less sure of a paradigm shift as such, there has been a gradual, uneven, yet shared shift by IFIs and governments from the ‘pillars cum privatisation’ approach towards more emphasis on the need for social forms of pension and assistance schemes.

Governments adopted other shared approaches to retrench social security systems – raising age and other criteria for pension eligibility, reducing entitlements, limiting cost-of-living indexation – in Russia and across much of Europe (Myles and Pierson, Reference Myles and Pierson2001). Reforms were regularly contested by pensioners’ organisations in both EU states and authoritarian Russia. Proposed reforms were often delayed or scaled back because of protests but the trends toward benefit contraction persisted (see Prisiazhniuk and Sokhey, Reference Prisiazhniuk and Sokhey2022). Research by Ebbinghaus (Reference Ebbinghaus2019) and others found that reforms increased inequality and poverty among pensioners, while many non-standard workers failed to quality for any benefits from insurance-based pension schemes. Under current labour market and demographic conditions, however, governments face inescapable trade-offs between financially self-sustaining pension systems and growing poverty, inequality and exclusion among retired populations (Zuk and Zuk, Reference Zuk and Zuk2018).

Trying to reverse demographic decline: divergent policies

Many of the governments under study adopted pro-natalist and family policies in efforts to slow or reverse declining birth rates. At a superficial level many of these policies appear similar – increased child benefits, longer and better-compensated parental leaves, preschool childcare, etc. – but approaches differ fundamentally between the EU15 on the one hand, Russia and major EU8 states on the other. EU15 states, in keeping with the Union’s socially liberal norms, have initiated or expanded policies to support work-family reconciliation as increasing numbers of women enter labour forces. Policies are generally designed to ease the burden of women’s care work while encouraging their labour market participation and promoting gender equality (Pascall and Lewis, Reference Pascall and Lewis2004; Ciccia and Sainsbury Reference Ciccia and Sainsbury2018). Policies support a dual-earner (rather than male breadwinner) model, and accommodate diverse family types including single-parent, LGBTQ and others. As noted above, these policies depart from the principles of welfare retrenchment. Increasing public expenditures to expand and subsidise care for preschool children and extend paid parental leaves, for example, are mainstays of EU15 approaches (Castles and Obinger, Reference Castles and Obinger2008). Success of these policies in raising birth rates has varied across EU states – the Scandinavian/Nordic states that have the most comprehensive family supports are most successful. However, success has been modest, with experts’ doubts that they would be sufficient to restore population growth (Frejka and Gietel-Basten, Reference Frejka and Gietel-Basten2016) borne out by Figure 1, which shows that overall EU15 fertility remained well below replacement levels.

Pro-natalist policies in Russia, Poland and Hungary, by contrast, combine family supports and baby bonuses with restrictions on women’s reproductive rights and nationalist, neo-familialist ideological pressures intended to re-traditionalise women’s roles. While making some concessions to the reality that most mothers are employed, governments of these three states sanction women’s roles as primarily caretakers and homemakers (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Iarskaia-Smirnova and Kozlov2022). Monetary incentives for childbearing and home-based care models play a major role in these cases. All three states have introduced progressive restrictions on access to abortion (which was generally available during the communist period), with Poland legislating, though not yet implementing, a total ban. There is also a strong ideological component to post-communist pro-natalist policies, which are couched in neo-familialist discourses that emphasise women’s responsibility to reproduce the nation. This approach has, however, produced only modest, temporary increases in fertility (Figure 1) and has largely failed to re-traditionalise women’s lives.

The difference in approaches to demographic policy across the cases merits explanation. Pronatalist policies in all cases are state-led – reversing demographic decline is a priority for governments concerned with maintaining labour forces and social security systems, not of citizens. But the liberal-democratic governments of the EU15 are self-limited by democratic norms to using incentives and supports in trying to influence citizens’ private behaviour. Governments have not used ideological pressures or coercive restrictions to produce more children for the state. The post-communist cases, by contrast, whether EU members or not, retain a strong historical legacy of welfare constructed by authorities to serve the state’s needs, as well as nationalist, traditionalist, and religious cultures that have grown stronger in the past fifteen years.

Integrating or excluding immigrants

International immigration is broadly recognised as a major political challenge in the EU15: a prominent and contentious issue in virtually every national election from 2015 to the present. As indicated above, Russia has also experienced massive labour migration since 2000, and it is a prominent issue in both national and regional politics (Cook, Reference Cook2022). Governments have made many efforts to limit and control these migrations. During the height of the MENA (Middle Eastern and North African) migration both the EU and individual member states tried to reduce and constrain the number of migrants reaching Europe. In the aftermath, most have restricted their asylum policies. With exceptions for Germany, Sweden, and to a lesser extent Finland and Norway, EU states have made limited efforts to integrate migrants, many of whom remain unregistered, with precarious statuses, living on the margins of societies, sometimes in refugee camps. Immigration has in several cases generated popular opposition, antipathy to migrants, welfare limitations, and support for nationalist and populist parties that challenge mainstream governing parties and militate against the success of integration efforts.

Russia’s large population of labour migrants also remains in precarious positions, most unable to register or legalise their status, working in informal sectors without rights, and confronting hostility and xenophobia in society as well as from political elites. In sum, in both the EU15 and Russia, immigrants have been subject to social exclusion and in some cases human rights violations. Here too, though, as with demographic policies, there are significant divergences between EU15 and Russian policies and practices. Unregistered labour migrants in Russia are subject to much greater degrees of popular violence, police abuses, extortion, arbitrary arrest and deportation. Many remain at risk of exploitation (Buckley, Reference Buckley2018). While many migrants have also been subject to violations of rights in EU15 states, rule of law and at least partial compliance with international and regional agreements sets some limits on infringements. Here too, different historical legacies shape what we have termed ‘welfare polities’ in contrast to ‘welfare regimes’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1996; Fenger, Reference Fenger2007; see our Introduction), and produce divergent approaches to broadly similar challenges. (With the exception of some intra-regional migration, EU8 states have largely refused to accept international refugees until the war in Ukraine in 2022.)

COVID-19 and ‘emergency Keynesianism’

Whilst it is too recent to be included in most of the analytical literature on ‘new social risks,’ the COVID pandemic is recognised as a major social policy challenge in all cases studied. The virus represents an exogenous shock that does not obviously derive from structural changes, though the intensity of global integration and cross-border exchanges across Russia and Europe homogenises populations’ exposure to its risks. The pandemic produced economic contraction, massive job losses, large-scale illness and premature death. Its sudden, intense impact challenged governments of mature welfare states to prevent economic collapse and mitigate social costs. The fallout of the current war in Ukraine may be expected to pose even greater challenges to social well-being (The International Economy, 2022).

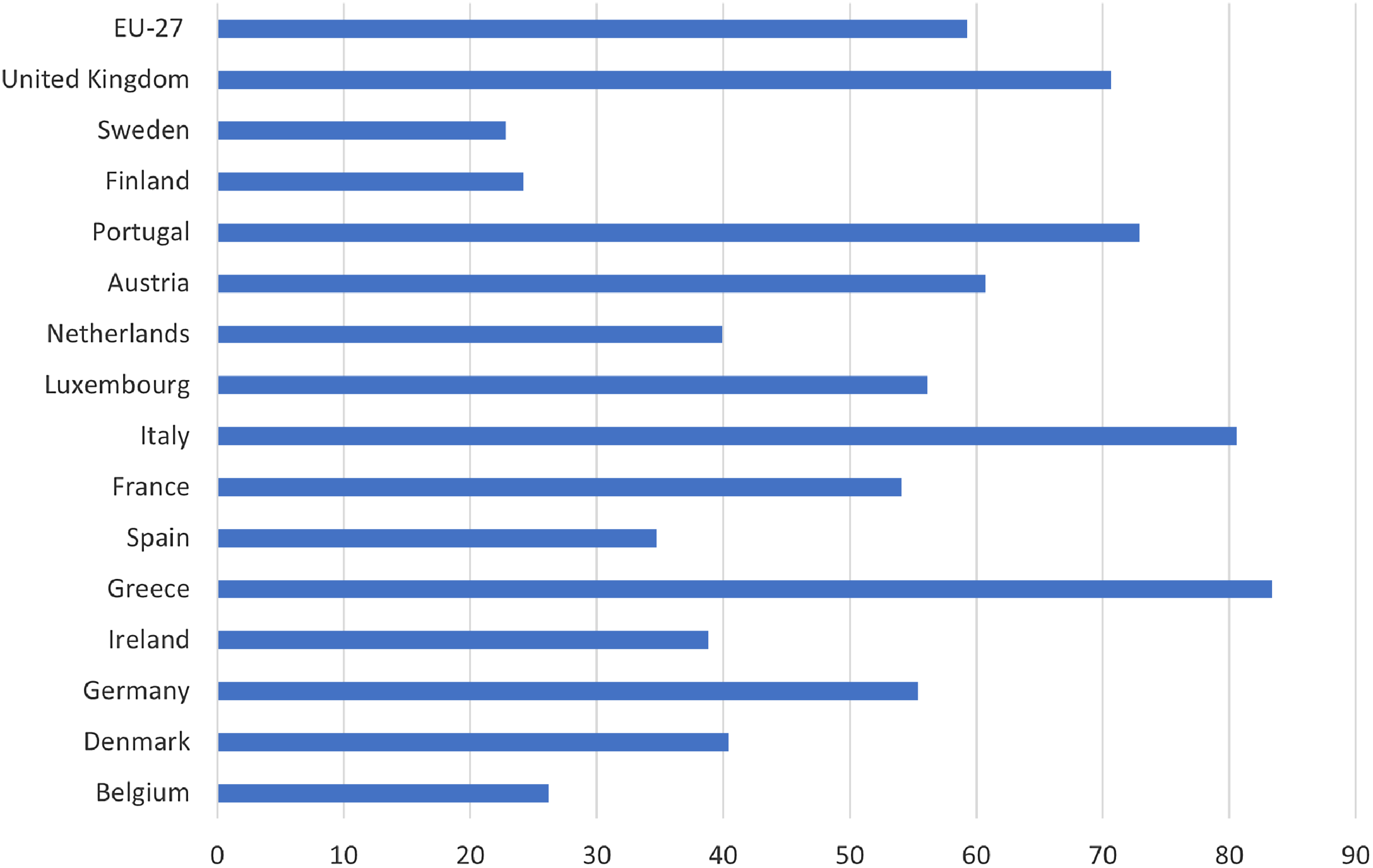

The sudden and intense shock of the COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic effect on welfare policy, producing what Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick and Moreira2021: 249) call ‘emergency Keynesianism’ across Russia and Europe characterised by massive use of deficit spending during economic crises, with the aim of supporting rather than challenging capitalist institutions’ (see Figure 3). In the face of the pandemic, austerity policies were halted and reversed. Russia as well as most EU8 and EU15 governments rapidly approved large-scale increases in social spending to fund job retention programmes, unemployment payments, minimum income schemes, sickness benefits, housing protections, new supports for working parents, and others (Aidukaite et al., Reference Aidukaite, Saxonberg, Szekewa and Szikra2021; Tarasenko, Reference Tarasenko2021). Figure 3 shows the amount of expenditures as percentages of GDP for all EU states in 2020. As the figure indicates, levels of expenditure were significant though they varied widely, from almost 4 per cent to less than 1 per cent of GDP across the cases. By comparison the Russian government spent about 2.7 per cent of GDP on COVID relief in 2020 (Dugarova, Reference Dugarova2022). Figure 4 presents Covid-related expenditures as a percentage of total state aid expenditures for the EU15, again showing the variations across cases.

Figure 3. Total State aid expenditure by Member State, as % of 2020 national GDP, breakdown between COVID-19 and other State aid measures.

Source. European Commission (2021).

Figure 4. COVID-19-related expenditure in EU-15 countries in 2020 (% of the total State aid expenditure).

Significantly, many of these programmes raised benefit payments or replacement levels, temporarily relaxed eligibility rules and/or extended inclusion in established programmes to additional population groups. New ad hoc benefits were created for workers in precarious (non-standard) employment. The account by Moreira and Hick (Reference Moreira and Hick2021: 261) ‘stresses the agility of crisis responses and this agility must be regarded as welcome, mitigating a great deal of social harm during the initial phase of the pandemic’. While, as shown above, levels of expenditure, structure, targeting and generosity varied across cases (see also Dugarova, Reference Dugarova2022), there was a remarkable common about-face from extended periods of austerity, privatisation and state withdrawal to ramped-up government intervention and large-scale social spending.

Both the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 and mitigation policies revealed the deep inadequacies of contemporary welfare states, showing starkly the effects of decades of labour market liberalisation and welfare retrenchment. They revealed that large swathes of citizen-workers would not meet eligibility requirements for unemployment and sickness insurance in a crisis. Benefit increases in mitigation policies implicitly acknowledged the insufficiency of existing benefit levels. In sum, the pandemic showed that after years of austerity, social insurance and benefit programmes provided too little and excluded too many. COVID also exposed the presence of significant socially-excluded populations. Except for some universal measures to cover vaccinations and treatment, most mitigation programmes did not reach informal, migrant, and seasonal workers, who often could neither work nor return home. Despite large-scale social expenditures, the pandemic produced increases in poverty, hardship and unemployment. Questions have been raised whether these programmes will be extended past COVID-19 and replace austerity, or whether they have been a temporary hiatus that will be followed by yet more stringent austerity to compensate for the high levels of emergency spending (Moreira and Hick, Reference Moreira and Hick2021). The impacts of the current war in Ukraine, especially the ‘cost of living’ crisis, large-scale energy shortages and movement of Ukrainian refugees into the EU, again bring into sharp focus questions of how costs will be spread across social strata and how much governments will intervene (The International Economy, 2022).

Bismarck and Beveridge

This themed section is part of a series intended to mark the eightieth anniversary of the famous 1942 Beveridge Report, Social Insurance and Allied Services. Beveridge’s model is relevant to several of the new social risks and policy challenges discussed herein. First, it presents an alternative to the Bismarckian social insurance systems that are based on standard employment and employment-linked contributory social insurance schemes (Glennerster Reference Glennerster1995; Lowe Reference Lowe1993). The pay-as-you-go pension systems in most of the studied cases follow Bismarckian principles. As the discussion has shown, both casualisation of labour markets and ageing populations have made these systems less and less sustainable. Moreover, efforts to slow population ageing by increasing fertility rates have largely failed. As well, governments have had to abandon some attempts to reform existing pension insurance system by partial privatisation. In fact, growth of non-standard employment has excluded increasing numbers of workers from contributory insurance schemes and from earning an adequate income through employment. Beveridge’s welfare model conceptualised an alternative system of social support that is arguably better-adapted to the realities of contemporary socio-economies.

Beveridge’s model relies more on universalistic and solidaristic principles. Though the system laid out in the 1942 report, which was never fully realised, assumed full employment and contributory social insurance, it was based on a guaranteed (i.e. not means-tested) basic income. Its key principles were universalism in social provision and a guaranteed minimum income below which no one should fall – a universal income floor (Deacon, Reference Deacon and Jones1993; George, Reference George, George and Taylor-Gooby1996). Current conditions of welfare states have produced renewed interest in Beveridge’s ideas as ways to address growth in inequality, poverty and social exclusion. The United Nations Research Institute on Social Development (UNRISD) has promoted basic income, as have the public intellectual Guy Standing and many other policy-makers and scholars.

While they usually lack the Beveridge label, in the real world prominent welfare reform proposals, experiments and policies follow Beveridge’s principles. Universal basic income is a fundamental platform of Italy’s Five Star Movement, which governed as part of a coalition from 2018 until 2021 and performed well in the fall 2022 national elections. Finland’s government has run an experimental program with basic income. Governments in several EU15 states, including Germany, have instituted basic pensions for workers in non-standard employment who do not qualify for traditional employment pensions. Poland’s government in 2016 initiated a generous universal child benefit that halved child poverty (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Iarskaia-Smirnova and Kozlov2022). Many of the COVID-era mitigation programmes were based on universal or equalising principles (even in the United States, where a broad program of flat payments to most households temporarily decreased high rates of child poverty). Basic income and flat-rate social pensions and other benefits have been used in partial and ad hoc approaches, to address immediate problems with current welfare systems. Some view the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis and the current cost-of-living crisis as an opportunity to address the accumulated deficiencies of contemporary welfare states with universalist policies, first and foremost a guaranteed basic income (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2020). However, even universal programmes would be limited to citizens and others with legal residence. Many immigrants to the EU and Russia are today informal, unregistered and typically excluded from all but emergency social provision.

Conclusion

This article has argued that EU15 and EU8 states and Russia have faced shared social risks, and that variations in policy responses derive from differences in historical policy legacies and welfare polities of these states. Whether convergent or divergent, however, these policy responses have for the most part failed to resolve the problems. The ‘new social risks’ considered here – namely, insecure employment and income, population ageing, unsustainable social security systems and large-scale international immigration – present both threats and opportunities for national governments and international actors. Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that governments could intervene at least somewhat effectively to mitigate social costs in crises. The current rapid integration of several million Ukrainian refugees into European societies, even in the face of growing domestic hardship in Europe, indicates that these governments and their populations do have the capability to include and provide for large numbers of people driven from their homes by war. The threats to living standards and well-being posed by historically high inflation and energy shortages in Europe are obvious; they present opportunities for government activism to again mitigate effects. Shared learning about successes and failures in the current geopolitical context is of vital importance. This will not be an easy task but it is now, we contend, a pressing priority for policy and research communities.

Acknowledgements

This article is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University).

The authors would like to thank Professor Elena Iarskaia-Smirnova as well as the reviewers for their helpful comments.