In recent years, the Monuments Men have become historical celebrities. Their belated and, in most cases, posthumous rise to fame is thanks in large part to current celebrities George Clooney, Matt Damon, Hugh Bonneville, and Jean Dujardin, among others, who portrayed them in a 2014 feature film directed by Clooney. One woman, Cate Blanchett, joined the heavily male production to play a character based on French officer Rose Valland. Together, the star-studded cast helped the film generate more than $180 million gross box office and home video sales worldwide in five years.Footnote 1 The history of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFA&A) division also has reached popular audiences through books published by retired oil entrepreneur Robert Edsel, including a New York Times number one bestseller, on which the film is based.Footnote 2 The Monuments Men Foundation, established by Edsel in 2007, further promotes public awareness of the history and legacy of the MFA&A and spearheaded an initiative to honor the officers with a US Congressional Gold Medal, bestowed on 22 October 2015. While the US government awarded the medal to men and women from 14 nations, the design itself, with input from Edsel, depicts American male soldiers in a mine, recovering a panel of the Ghent altarpiece, a Rembrandt self-portrait, and Vermeer’s Astronomer. Footnote 3

Framed in a similar narrative, the Monuments Men film above all celebrates the role of American men in the recovery of Nazi-looted art during the final days of the Third Reich. While one should not expect a feature film to convey history in all its complexities, this Hollywood portrayal oversimplifies American greatness to the brink of hagiography. The film narrative – US-centric, largely masculine, and triumphant – distorts the history of the MFA&A by eliding the role of Western Allies and women, while failing to acknowledge the plunder of Jewish assets in the context of the Holocaust and their incomplete restitution to the rightful owners.

The scholarly literature on the MFA&A and art restitution, while reaching far smaller audiences, has grown dramatically since the mid-1990s. Following the 1994 publication of writer Lynn Nicholas’s pioneering book The Rape of Europa, numerous studies have elucidated the administrative machinery of Nazi art plunder, the US-led Allied recovery effort, national restitution policies in Western Europe, and the belated, inadequate restitution of Jewish assets.Footnote 4 Building on this ample body of research, this article places the heroic narrative of the Monuments Men in a broader historical context through a case study of British Major Anne Olivier Popham (1916–2018). The first section addresses British art recovery and restitution services within the broader MFA&A, drawing on British and US national archives. The second section introduces three Monuments Women: US Captain Edith Standen, French Captain Rose Valland, and British Major Anne Popham. The third section addresses Popham’s service in Bünde, Germany, from November 1945 to October 1947, based on firsthand testimony provided in a professional diary housed at the Imperial War Museum in London and my 2014 interview conducted at her cottage in East Sussex. A fourth and final section analyzes Popham’s perspectives in light of the incomplete restitution of Jewish-owned works of art, as national interests overrode the MFA&A’s mission of restitution to rightful owners. At stake in this study is a greater recognition of Allied cooperation among women and men, all of whom served the noble goal of restitution that ultimately was thwarted by national interests in the early postwar years. The experiences of Major Anne Popham pointedly illustrate the goodwill of many Allied cultural officers, bringing into sharp relief the ongoing need for transnational cooperation in our own times – beyond rhetoric – in the restitution of Jewish assets.

Transnational art recovery and repatriation

Clooney’s film focuses on the role of American men in the art recovery process, featuring dramatic rescues in the heat of battle as the Third Reich was crumbling. The film gives merely token roles to foreign characters played by Briton Hugh Bonneville and Frenchman Jean Dujardin. Both are killed during rescue operations, rather conveniently leaving American characters played by Clooney, Damon, John Goodman, and Bill Murray to pursue their proclaimed mission to save Western civilization. The work of the actual Monuments Men who rescued art in war zones, including James Rorimer, Thomas C. Howe, and George Stout, was indeed heroic and worthy of a great feature film. Yet their own firsthand accounts repeatedly acknowledge the indispensable role played by officers from other Allied countries.Footnote 5 While the MFA&A was a US-led operation, established by President Franklin Roosevelt at the end of 1943, the art restitution effort relied on the leadership, talent, and dedication of some 350 officers from 14 Western Allied nations.Footnote 6

British experts and diplomats, in particular, played a key role in the division’s early operations and in formulating postwar restitution procedures. One individual was Sir Leonard Woolley, a renowned archaeologist best known for his excavations in the 1920s in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur. His resulting publication, Ur of the Chaldees (1929), earned him international esteem in the early 1930s and a knighthood in 1935.Footnote 7 With the outbreak of war, he was commissioned to serve in the Intelligence Division at the War Office with the acting rank of captain. In his spare time, he began compiling a card index of British art and monuments in the event of war damage.Footnote 8 Woolley’s efforts quickly extended beyond Britain, however, as the military sought his expertise in Italian Libya, where Italy had regained territory in the summer of 1941 that had been held briefly by the British. Fascist propaganda accused British soldiers of vandalizing heritage sites with graffiti and destroying statues and provided photographic evidence. Whether the photos were staged by the Italians themselves, as Woolley later claimed, the propaganda had the intended effect and further stoked Italian and Libyan animosity toward British occupation forces. The incident forced British political and military leadership to recognize the strategic value of heritage protection, and Woolley was named archaeological adviser to the Directorate of Civil Affairs in October 1943 at the rank of lieutenant colonel.Footnote 9

Another top British MFA&A officer was Colonel Geoffrey Webb, Slade Professor of Fine Art at Cambridge. In December 1943, as plans for the invasion of Normandy were underway, Woolley appointed Webb as British MFA&A adviser at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in London. In early 1944, he became the overall head MFA&A adviser.Footnote 10 A short biography prepared by US authorities described Webb as “very capable,” “energetic,” “a very straight thinker,” with “a wide range of interests.”Footnote 11 American Monuments Man Thomas C. Howe later depicted Webb in more colorful terms – a “tall, rangy colonel who reminded me of a humorous and grizzled giraffe.”Footnote 12 An effective leader, he oversaw the drafting of the first MFA&A directives distributed to cultural officers and would later head the MFA&A’s operations in the British occupation zone in Germany.Footnote 13

Just as civilian and military conservation efforts developed during the war, so did Allied planning for the restitution of assets seized by the Axis powers. In early 1943, the British government spearheaded a declaration that would serve as a warning to Axis and neutral powers that the Allied countries would not recognize transfers of property carried out in Axis-occupied territories. On 5 January, 17 governments, including the Big Three powers and the French National Committee, signed the Inter-Allied Declaration against Acts of Dispossession Committed in Territories under Enemy Occupation and Control, vowing “to do their utmost to defeat the methods of dispossession practiced by the governments with which they are at war against the countries and peoples who have been so wantonly assaulted and despoiled.”Footnote 14

As the war against Germany continued, Allied diplomats debated proposals to create an international restitution commission charged with advising national governments, an idea widely supported by cultural advisors in the US and Western Europe.Footnote 15 A group of British experts who served in the advisory Macmillan Committee reported to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden in September 1944 that such an international commission was a sine qua non of the envisioned restitution process: “[I]t is essential that it should derive its power from the national Governments concerned” and “should be created at the earliest possible moment so that it can advise the Allied Governments during the period of military control and, in the meantime, under direction prepare a programme of restitution of loot and stolen material.”Footnote 16

Yet the prospect of a supranational restitution organization raised thorny questions about the sovereign control of property. Eden considered the control of assets fundamental to state sovereignty: “We regard these Governments as solely responsible for the treatment of property within their own borders.”Footnote 17 Richard Law of the British Foreign Office similarly argued that “the Allies would never consent to allowing questions of ownership of works of art in their territory of arising out of transactions which had taken place in their territory to be determined by an ‘Allied international authority.’” He found it “difficult to see on what legal principles such an authority could work, except upon the rules of local law,” which only could be “interpreted by local courts and not by any external body.”Footnote 18

Eventually, top officials in all four occupying countries rejected proposals for an international restitution commission with broad powers. The French, who were granted an occupation zone at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, opposed giving such a body the power of trusteeship, while British and American authorities feared that an international organization might lead to intelligence leaks and civilian interference in military operations. Most important, the Soviets wanted full control over “trophy art” in their occupation zone and rejected all plans for an international body charged with cultural restitution.Footnote 19 The failure to establish an international restitution commission left national governments ultimately in control over cultural assets repatriated to their territories, creating a tension between the national interest of enriching cultural patrimony and ensuring restitution to the rightful owners.

After the German surrender and division of the country into four occupied zones, the Allies continued to debate the very definition of restitutable property amid broader reparations negotiations. The French intended to recover a broad range of assets, while the United States and Britain aimed to spur German economic reconstruction and limit the burden of restitution. Meanwhile, the Soviets refused to allow the shipment of goods from their zone without established parameters.Footnote 20 All sides finally approved a compromise proposed in December 1945 by General Lucius Clay, then deputy military governor of the US zone. Restitution would be “confined to cultural objects whose identification is easy and whose ownership is well known,” allowing the program to broaden to other assets with improvements in procedures and facilities. Claimant countries – not individuals – would submit claims to restitution headquarters in each occupation zone, and experts from the Allied countries would be invited to Germany “as representatives of the claimant Governments and not as representatives of firms or individuals of such countries.”Footnote 21

In the British zone, the investigation and restitution of plundered assets was overseen by the Property Control Branch of the Reparations, Deliveries and Restitution Division (RDR) in the Control Commission, British Element. Serving as the chief British investigator was Squadron Leader Douglas Cooper, an art collector and critic who notably discovered papers of the Schenker transport company in Paris with crucial information on art shipments from France to Germany.Footnote 22 British art recovery in the several weeks after the German surrender included artworks and archives found at the Schönebeck mine, which would become part of the Soviet-occupied zone in July 1945. In the few days prior to Soviet control of the mine, the British moved the stash safely inside their zone, sheltering the items in a former imperial palace in Goslar. By late August 1945, they consolidated all items recovered in their zone at Schloss Celle, some thirty miles northwest of Brunswick.Footnote 23 Many of these works had been evacuated from German universities, libraries, and museums, including the Berlin State Museums, though the caches also contained objects plundered from Jewish collections. In principle, the British Foreign Office, Colonial Office, and Trading with the Enemy Department agreed in August 1945 that “all Jewish identifiable property which is recovered will be restored to its rightful Jewish owners or their heirs or successors.”Footnote 24 In reality, however, the overriding mission of the RDR – as defined by the Allies in December 1945 – was repatriation of assets to countries of origin and not restitution to private owners, an objective reflected in the professional diary of Monuments Woman Anne Olivier Popham.

The Monuments Women

The very terminology of “the Monuments Men” elides the role of women in key leadership positions in the MFA&A. While male cultural officers carried out the first phase of recovery operations during and shortly after active combat, the MFA&A recruited men and women from Western Allied countries to assist with the subsequent mammoth task of repatriating millions of artworks, books, and archives to their countries of origin. US Captain Edith Standen, for example, oversaw the Wiesbaden Collecting Point from March 1946 to August 1947.Footnote 25 French Captain Rose Valland, who had spied on Nazi looting operations at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris, served the MFA&A in Baden-Baden and West Berlin. She played a central role in the repatriation of works of art to formerly occupied countries and worked closely with German curators to reopen art museums.Footnote 26

Valland inspired the only significant female character in the Monuments Men film: Claire Simone played by Cate Blanchett. The film narrative ends with dramatic art recovery scenes in May 1945, thus omitting the later restitution process, when Valland became a prominent figure in the MFA&A. In some ways, the film character captures the actual work of Valland in occupied Paris. Claire is a French patriot and seethes authentically as she watches Hermann Göring admire looted works of art on display for him at the Jeu de Paume museum and handpick pieces for his own collection. Yet, in a clumsy and entirely fictional Hollywood romance, the Claire character tries to seduce an upstanding married American officer played by Damon. The portrayal is all the more problematic given that Valland had a long-term female partner, Joyce Heer, and both were interred in the Valland family burial vault.Footnote 27

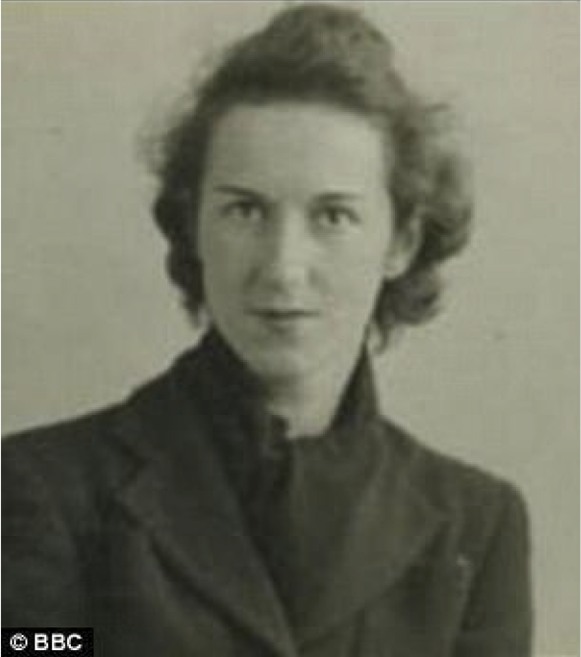

British Monuments Woman Major Anne Olivier Popham also served in a position of authority (see Figure 1). Her firsthand accounts, written in diary entries and told in an interview several decades later, provide rich evidence for social historians, conveying her interactions with Germans, foreign MFA&A officers, and her British male colleagues. Like all personal narratives, however, they provide the perspective of one individual and raise questions about the reliability of memory. They are, therefore, most effectively mined alongside other evidence – official reports, correspondence, and other officers’ memoirs. Taking a broader view of the MFA&A’s operations, this array of sources reveals a lacuna in Popham’s professional diaries and oral history: the plunder and restitution of Jewish assets.

Figure 1. Anne Olivier Popham (courtesy of the Estate of the late Anne Olivier Bell).

Like Standen and Valland, Popham was an educated, single woman at the end of the war who chose to take advantage of opportunities offered by the MFA&A. She joined the division amid a widespread belief in Britain that women should abandon wartime work and military service and return to the home, serving the country as wives and mothers.Footnote 28 Throughout her life, Popham alternated between respecting and bucking social conventions, a duality inherited from her parents. She was born in 1916 to Ambrose Popham, head of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, and her mother, Brynhild Olivier, a cousin of Laurence Olivier associated with the Neo-Pagans, a group of writers and Cambridge graduates who embraced “simple life” socialist practices of vegetarianism, camping, and nude bathing. Brynhild’s social circle included members of the intellectual and literary elite, such as Bloomsbury writer Lytton Strachey and economist John Maynard Keynes.Footnote 29

Popham received a varied education, with stints at a vegetarian school run by Marjorie Strachey, younger sister of Lytton, and at St Paul’s Girls School in West London.Footnote 30 Drawn to the arts, she briefly studied opera in Germany and acting at the Central School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art in London, but soon realized her true talents lay elsewhere. Her father encouraged her to enroll in a new school of the arts – the Courtauld Institute – where she studied with Geoffrey Webb, her future MFA&A supervisor. Popham studied a wide range of art historical topics, including ancient Egyptian art, the architecture of Westminster Abbey, and the Dutch Old Masters.Footnote 31 Through this cultural community, Popham met Graham Bell, a married South African artist associated with the Euston Road School of realist painters. The friendship developed into an affair, her first great romantic love. Bell painted her portrait in his characteristically spare, realist style, and the Tate Gallery purchased the canvas in 1944 (Figure 2).Footnote 32

Figure 2. Graham Bell, Miss Anne Popham, 1937–38 (© Tate, London/Art Resource, New York).

Bell promised to divorce his wife so he could marry Popham, but the war interrupted their plans. He joined the Royal Air Force and was killed in a training exercise in 1943, a loss so profound that she felt like a widow.Footnote 33 She plodded away at a government job in the Ministry of Information through the end of the war but grew tired of the work. Her fortunes changed when she met, in her words, a “very posh” young man at a party who had joined the MFA&A and encouraged her to do the same. She recalls that she was “concerned about all the bombing and destruction” on the continent and knew she “had something of value to offer.” Her training in art history at the Courtauld made her a strong candidate for the cultural officer corps, and with no romantic or family commitments keeping her at home, she became a civilian officer in the MFA&A at the rank of major.Footnote 34

A British Monuments Woman in Bünde

Popham arrived in Germany in November 1945 and was stationed at Bünde in Westphalia, the MFA&A Divisional Headquarters in the British zone. The MFA&A office was established in a requisitioned German home, part of a British-occupied sector cordoned off from the rest of the city with barbed wire. Although Popham spoke German, her interactions with German people were mostly limited to the office cleaning lady, whom she tipped with cigarettes. She felt some sympathy for the residents of Bünde and later observed: “It must have been miserable for them to see us taking over their homes.”Footnote 35 As the manager of the Bünde office, Popham coordinated the art recovery fieldwork of male officers and oversaw the office work of typists and assistants. Her four-volume professional diaries held at the Imperial War Museum in London record her daily tasks, conversations, and meetings. The entries convey little heroism in the officers’ day-to-day endeavors, characterized by a perpetual shortage of transportation and supplies. On one occasion, an officer phoned to tell her his car’s battery had died and the driver had to push it back to town; another reported clutch and steering problems with a Mercedes, another that his car’s tires had blown out.Footnote 36 She arranged these vehicle repairs, managed coal supplies to heat the MFA&A office, and reminded typists they needed to arrive to work on time.Footnote 37 Popham would later recall that much of her time was spent merely trying to reach people by telephone on faulty lines, a source of endless frustration.Footnote 38

More substantively, Popham also helped develop restitution procedures for Westphalia, ensuring that claims were centralized in Bünde, then forwarded to the RDR in Minden.Footnote 39 She and her British colleagues discussed French demands for German-owned works of art as “replacement in kind” to restore the French patrimony, an approach ultimately rejected by British and American authorities.Footnote 40 One of her key responsibilities was coordinating the restitution of bronze church bells that had been seized by the Nazis across Europe for recycling into bullet casings and other weapons. The Germans had shipped some 50,000 bells to the Third Reich and, by the end of the war, more than 2,000 were found intact in Hamburg scrap yards.Footnote 41 Popham fielded restitution requests by priests, local officials, and townspeople eager to recover their religious and sonic heritage.Footnote 42 The issue of bell restitution also interested US officials due to the metal’s value and potential impact on German reparations. In early November 1946, Popham oversaw a meeting to discuss the claims process, attended by American occupation authorities and British MFA&A officers stationed in other German cities. She later remembered this meeting as one of the most important moments in her service to the MFA&A, as she assumed a leadership role among male officers from various departments in both occupation governments.Footnote 43 Her diary entry notes that after the meeting, the attendees all had lunch together at the officers’ club, indicating her ability and willingness to socialize with male colleagues.Footnote 44

Popham’s position also required keen diplomatic skills, as she dealt directly with claimants from several European countries. When priests from across Western Germany showed up at the Bünde office to claim bells stolen from their churches, it was Popham who listened to their stories and told them they would have to wait for the restitution system to proceed along official channels.Footnote 45 She coordinated visits by French, Belgian, and Dutch MFA&A officers who submitted claims to works found in the British zone and, at times, attempted to circumvent the frustratingly slow restitution process. Her diary entry from 11 November 1946, for example, summarizes a meeting with Dutch cultural officers: “Long discussion over the same old ground, about slowness of restitution and necessity for Dutch investigations. Supported them but delivered a warning … against too much independence. [They] must work with and report to the MFA&A.” She added with some derision that the Dutch officers then enjoyed lunch in the officers’ mess and feasted on “100 oysters.”Footnote 46

Popham’s diaries also reflect efforts by Allied officers to thwart official restitution processes. An entry on 30 April 1946 notes the “irregular” release of two paintings from the Netherlands to an unnamed US representative. A British official at the RDR told her the transfer “was arranged in Berlin on a high-level old boy” network and that he had been “instructed to issue release authority.”Footnote 47 In July 1946, she noted a possible American theft of works from the Wallraf-Richartz museum in Cologne held for safekeeping at the Ehrenbreitstein fortress. She noted the affair was causing a “fuss in American papers,” with several high-ranking officers investigating the charges.Footnote 48 The New York Times ran the story, reporting that two American officers and one British officer were questioned about the disappearance of $250,000 worth of paintings, including a Rubens.Footnote 49

Popham faced even greater frustration dealing with British officers outside the MFA&A who felt entitled to dispose of German-owned cultural objects for their personal use. The commander-in-chief of the British Zone, Air Marshall Sholto Douglas, wished to obtain 15 paintings from the Krupp collection,Footnote 50 held by the Allies while Alfried Krupp faced war crimes charges for producing weapons with slave labor.Footnote 51 Popham noted on 19 October 1946 that her office was instructed to deliver the paintings to Douglas’s “blue special train,” due to arrive at Brunswick station in four days. An aide de camp informed her that the commander’s staff would supply 15 blankets, one to protect each of the paintings.Footnote 52 The request prompted a flurry of communications and concerns about which army division would insure the paintings. The commander “rang wrathfully” after a few months’ delay but did receive some of the pictures. His staff again contacted the Bünde office in March 1947 and requested to have them cleaned.Footnote 53 Douglas also told British Air Marshal Philip Wigglesworth, the head of the British Air Forces of Occupation, that he too might receive some nice pictures. Wigglesworth was displeased with the decor of his residence in Rinteln and coveted some landscape paintings from the Bückeburg palace, home of the Schaumburg-Lippe princely family.Footnote 54

The instrumentalization of German-owned art went beyond British top brass. At the end of 1945, General Lucius Clay, deputy governor of the US-occupied zone, approved the shipment of 202 paintings from the Kaiser Friedrich Museum and Deutsches Museum in Berlin to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Ostensibly, he was “disturbed by the possible future of Berlin” and did not wish to return the masterpieces “under such conditions.”Footnote 55 Most American MFA&A officers working in Germany were unmoved by Clay’s “safekeeping” argument, which was uncomfortably similar to rhetoric used by the Nazis, and strongly opposed the measure. Thirty-two of the 35 officers in the field supported a protest that became known as the Wiesbaden Manifesto; 24 of them signed the document, and eight otherwise expressed support.Footnote 56 According to then director of the Wiesbaden Collecting Point, Walter Farmer, it was “the only group protest by overseas officers against orders in the Second World War.”Footnote 57 US Captain Edith Standen distributed copies to offices in Germany and the United States, including Harvard’s Fogg Museum.Footnote 58 Despite the protest, the paintings were exhibited in major cities across the United States before returning to Wiesbaden in 1949, an operation that fuelled lasting resentment among MFA&A officers.Footnote 59

In contrast to this sense of competing interests with the top brass outside the MFA&A, Popham described a loyal camaraderie with her male colleagues within the division.Footnote 60 She felt respected by them and developed long-lasting friendships with several British officers, echoing Valland and Standen’s enduring cordial relationships with male cultural officers.Footnote 61 Through her upbringing and education, she had come of age within the British cultural elite and socialized easily with colleagues. She recalled dining at the officers’ mess hall, enjoying cocktails, and dancing. On weekends, she travelled with MFA&A colleagues in the British zone, visited cultural officers stationed in other cities, and danced at their officers’ halls. Despite some discomforts and material shortages, she remembered her time in the MFA&A as a rather grand adventure.Footnote 62

Nothing in Popham’s diaries contradicts her memories of camaraderie in the mixed gender division. In contrast to this positive account, historian Lucy Noakes paints a far different picture of women who served the British female-only Auxiliary Territorial Service in World War II, “described by male soldiers variously as ‘good time girls’, ‘sexually immoral’, ‘a league of amateur prostitutes’, and ‘bloody whores.’” Noakes finds that men who served in non-combat arenas defended their status the most against women, perhaps feeling their “masculinity was somehow lacking when compared to that of the male ‘heroes’ and ‘warriors’ in the front line.”Footnote 63 The MFA&A provides an interesting contrast, as the cultural officers – male and female – repeatedly were forced to assert their status and authority when dealing with other military divisions. Within this highly educated corps, the esteem enjoyed by Popham, Valland, and Standen may have been precisely due to their rank, credentials, and training. It is worth investigating whether typists, clerks, and soldiers of both genders in support positions felt similarly respected by male and female cultural officers.

Popham’s stint in the MFA&A was but one chapter in a storied life. She returned to England in 1947 and continued to work in cultural affairs, organizing exhibitions across Britain for the Arts Council. In 1952, she married Quentin Bell (no relation to Graham), son of Clive and Vanessa Bell and nephew of Virginia Woolf, further ensconcing Popham into the heritage of the Bloomsbury group. In some ways, she conformed to a conventional middle-class lifestyle, focusing her energies on domestic life and raising three children. Bloomsbury member Duncan Grant even called her “an exemplary housewife.”Footnote 64 By mid-life, however, she was drawn to literary pursuits and contributed to the Bloomsbury legacy by helping Quentin research his 1972 biography of Woolf. She then took on her own ambitious project, editing Woolf’s five-volume diary, published between 1977 and 1984. For this work, Popham was appointed a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and in 2014 was awarded a British Empire Medal for her service to literature and the arts. Together, she and Quentin continued to promote the Bloomsbury legacy and established an independent charitable trust to preserve the Charleston farmhouse, the group’s traditional gathering place near Lewes. During an annual Charleston festival, she sat in the front row for all of the events and corrected any errors uttered by speakers or attendees. She died on 18 July 2018 at the age of 102, the last living member of the British MFA&A.Footnote 65

As I spoke with Popham in her cozy East Sussex cottage in mid-December 2014, the sitting area brightened by late afternoon sunshine, she seemed delighted to share memories about her time serving in the MFA&A – the adventures, travels, and dancing as well as the daily frustrations and tensions with officers outside the cultural division. Oral history offers the researcher great personal reward, especially when conducted with such an exceptionally admirable subject. Yet it also produces inherent methodological dilemmas. Popham’s testimony – written and oral – reveals the limited perspective of an individual, as her position did not require her to confront the most significant failure unfolding in the MFA&A: the incomplete restitution of cultural assets to rightful owners, especially Jews.

The incomplete restitution of Jewish assets

At the end of the Monuments Men film, set soon after the German surrender, Clooney’s character reports tidily to President Harry Truman that “everything from paintings to sculptures, tapestries, even jewelry is being returned.” The film, like Edsel’s book, eschews the protracted and exceedingly complicated restitution process. Investigators knew a great deal about the machinery of Nazi art plunder by March 1945, as evidenced in an MFA&A report for the SHAEF distributed to the British Element Control Commission and the British political adviser. Even before the defeat of Germany, the MFA&A was aware that most of the plunder had been privately owned and, above all, had targeted Jews. While acknowledging that investigations were still underway, the report found that “Germany’s looting activities have been largely connected with her persecution of the Jews” and that “it is individuals of the occupied territories rather than the States themselves who have been robbed.” Showing an early awareness of the role of art sales in the plunder, the report also finds that, by “ruthlessly exploiting an artificially favorable exchange position, Germany was able to make an apparently ‘legal’ purchase almost as attractive as a bare-faced theft.” Thus “the ownership of the majority of works of art which appear on the international market must be considered in doubt until the contrary can be certified.”Footnote 66 Officers in the field recovered vast stashes of Jewish religious objects, books, and archives. By 1946, the Offenbach collecting point in the US zone specialized in managing the conservation and restitution of more than three million Jewish items.Footnote 67 All MFA&A officers thus were aware of the vast plunder of Jewish cultural and sacred objects.

Strikingly, the words “Jew” and “Jewish” rarely appear in Popham’s diary, though she was well aware of Jewish losses. Carrying out her first assignments with the MFA&A in London, before she left for Germany, she read extensive intelligence reports on the plunder of Jewish collections.Footnote 68 Yet her diary entries rarely specify Jewish dispossession. An entry on 27 December 1945 notes that the staff “discussed indexing of works of art in British zone acquired in occupied countries,” with no mention of likely Jewish ownership. Later that day, Popham noted: “General Robertson had ruled that objects found in British zone emanating from occupied countries, by whatever means acquired, should be made available for restitution.”Footnote 69 In May 1946, she wrote to Dutch and Belgian MFA&A officers about works of art that had been purchased in their countries during the occupation by museums in Kiel and Lübeck, without any indication they may have been plundered from Jewish collections. After Allied investigations helped return the objects to countries of origin, some German museums demanded compensation. The Germans, she noted, “will have to cope with questions of compensation sometime.”Footnote 70 An exceptional, but brief, mention of Jewish ownership appears in her entry for 26 August 1946: “[W]rote OMGUS about Jewish property,” with no further elaboration.Footnote 71

Why only the occasional, cursory references to Jewish assets when investigators had directly linked Nazi art plunder to anti-Semitic persecution? The nature of the diary itself has limitations as a historical source as it often reads like a meeting and telephone log – neither a journal with expansive observations nor a register with the sort of provenance information that MFA&A officers noted on index cards for individual objects. The professional diary thus neglects any more profound observations that Popham may have made. Moreover, many objects under British control had been evacuated from German institutions, including Berlin State Museums, and were not Jewish-owned.Footnote 72 Most important, when Popham refers to works originating from occupied territories, she addresses the country of origin and not private owners. This tendency reflects Allied restitution procedures, which repatriated items to countries of origin, not to individuals. A telling example involves works from Ribbentrop’s collection found in the British zone. On 17 January 1946, she wrote to the British RDR office in Minden that “the provenance of the pictures and textiles is unknown, though in the case of the former, there is (visible) proof of French residence in [the] case of 17 and a supposition that many more emanate from France.”Footnote 73 “Provenance” here refers to the country of origin, not the prior owner, which was entirely in line with the MFA&A’s repatriation objectives. France claimed 30 of the pictures, one of which – a Monet water lily painting – had been plundered in September 1940 from the temporary refuge of prominent Jewish dealer Paul Rosenberg near Bordeaux.Footnote 74 The French government held the canvas in trusteeship until the Rosenberg heirs identified and claimed the painting in late 1998, finally receiving it on 29 April 1999.Footnote 75 Popham’s emphasis on the works’ French provenance thus reflects a broader tension in the MFA&A mission between national repatriation and restitution to individuals.

By the late 1940s, the Western Allies began phasing out their restitution operations in anticipation of the transfer of sovereignty to West Germany. US civilian and military leadership, in particular, was eager to end Allied oversight of the restitution process. Yet the collecting points all still held numerous “heirless” cultural objects that had not been repatriated. Traditionally, heirless assets had reverted to state control, as they did in formerly occupied countries that received works of art from the MFA&A. But for American, French, and British authorities and Jewish organizations, this solution was morally and politically unjustifiable in the case of Jewish assets from the German Länder. Each of the Western powers designated successor organizations to serve as trustees of heirless assets and to distribute much of the recovered property to Jewish communities.Footnote 76

Unable to agree on a single restitution law for each of the three Western zones and West Berlin, the Western Allies created four different statutes. On 10 November 1947, the United States enacted Military Law 59, which provided for a successor organization that would distribute heirless assets to the Jewry worldwide. In June 1948, the US Military Government gave this authority solely to the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization (JRSO), founded in New York in 1947. Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, also created in New York the same year, became the cultural branch of the JRSO and distributed heirless objects.Footnote 77 The JRSO also served the three Western sectors of Berlin beginning on 9 May 1951 and, in all, distributed some half a million books, Torah scrolls, and ceremonial objects to the Jewish diaspora: 40 percent to the United States, 40 percent to Israel, and 20 percent to other communities around the world.Footnote 78

On 12 May 1949, the British Military Zone Government enacted its own Law 59 and set a restitution deadline for the following month, on 30 June.Footnote 79 The MFA&A continued to accept claims for several months past the official deadline, until Brigadier CFC Spedding of the RDR informed the Bünde office: “We are now under strict injunctions to accept no more restitution claims of any nature, however hard individual cases may be.”Footnote 80 In August 1950, the British Military Government established the Jewish Trust Corporation (JTC) as a successor organization in its zone, and the French established a branch in 1952.Footnote 81 Initially intended to serve Jewish communities outside Germany, the successor organizations also negotiated with new Jewish communities inside Germany, composed in part by foreign Holocaust survivors, to distribute heirless communal assets and compensation for indemnification claims.Footnote 82 Altogether, by 1957, the successor organizations had acquired assets worth some 300 million Deutschmarks.Footnote 83

Despite continued restitution efforts by the JRSO, the JTC, and the Federal Republic of Germany, the proclaimed mission of the Western Allies to restore works to rightful owners, especially to persecuted Jews and their descendants, remained elusive. For instance, the British government never compiled a list of assets lost by British subjects, such as Clarice de Rothschild, whose assets were stolen by the Soviets from their occupation zone of Austria, and no special measures were taken to prevent plundered works from being sold on the London market.Footnote 84 Restitution to individuals, moreover, depended on the efforts of national agencies after repatriation to countries of origin. The governments of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands considered heirless any object that had not been successfully claimed by the late 1940s and, altogether, selected thousands of pieces for display in state museums, ministries, embassies, and other public buildings. Of the three governments, the Dutch government appropriated the highest number of objects at around 5,000, followed by more than 2,000 in France, and 639 in Belgium. Cultural property disputes over works in the custodianships continue to this day.Footnote 85

An analysis of British contributions to the MFA&A, and, in particular, the work of Major Anne Olivier Popham, reveals dimensions of art recovery and restitution operations that are often neglected in popular narratives about the American Monuments Men. First, while the MFA&A was a US-led operation, the art restitution effort relied on the leadership, talent, and dedication of members from 13 other Western Allied countries, notably British art experts, diplomats, and officers. Second, the very terminology of “the Monuments Men” elides the role of women in important managerial positions. Third, art restitution to rightful owners, especially Jewish victims of the Holocaust and their heirs, remained incomplete due to the transfer of responsibility to national governments and successor organizations, such as the Western Allies, especially when the United States retreated from restitution procedures. Fourth, Popham’s firsthand testimony reflects a consistent instrumentalization of art by those in positions of power. British cultural officers found greater solidarity with American MFA&A colleagues who also opposed the tendency of top brass in both armies to dispose of cultural objects as they saw fit. Finally, from a methodological perspective, this case study underscores the importance of comparing firsthand accounts, on which much of the more heroic literature is based, to official reports, correspondence, international agreements, and other documentary evidence. Personal testimonies yield riveting detail, while government archives reveal the elaboration of policy that ultimately circumscribed the officers’ accomplishments.

In recent years, non-binding agreements emanating from international conferences held in Washington, DC, in 1998, Vilnius in 2000, Prague in 2009, and Berlin in 2018 have proclaimed a wide commitment to the continued restitution of Jewish assets. This ongoing mission requires even greater transnational cooperation, the revision of national laws that hinder restitution, such as statutes of limitations, and investment in provenance research with the open digitization of ownership records. Such complicated matters could not easily be captured in George Clooney’s film on the Monuments Men, but the production team knew the public relations value of inviting Anne Popham Bell to the London premiere. She was rather bemused by all the fuss as she glided along the red carpet in a wheelchair, and kept Clooney’s ego in check, telling him: “Sorry, but I don’t know who you are.” She found the glamour and media attention exciting but, in the end, was not terribly impressed by the film: “It was all about the Americans.”Footnote 86

Acknowledgments

The author thanks participants of the March 2017 conference, From Refugees to Restitution, held at the University of Cambridge, and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. Special gratitude goes to conference organizers Bianca Gaudenzi and Lisa Niemeyer, who also commented on several drafts and brought the entire special issue to fruition.