The verb “to conjure” is a complex one, for it includes in its standard definition a great range of possible actions or operations, not all of them equivalent, or even compatible. In its most common usage, “to conjure” means to perform an act of magic or to invoke a supernatural force, by casting a spell, say, or performing a particular ritual or rite. But “to conjure” is also to influence, to beg, to command or constrain, to charm, to bewitch, to move or convey, to imagine, to visualize, to call to mind, or to remember. —Rachael DeLue Reference DeLue2012, para 1.

When we create with our Brown hands, feminine energy, and full spirits, we conjure. To exist, survive, and thrive in these bodies is a continuous act of conjuring. Our walks conjure. Our smiles conjure. Our tears conjure. Our laughs conjure. Our words conjure. Our artworks are conjurings. We, a Black/Filipina-American woman, a Dominican-American, and a Black-American woman, are guided by our solidarity with one another and all other Black and Brown female identifying persons whose raced and gendered subjectivities exist both inside and outside of colonization, white supremacy, and patriarchy. We bring to life our colored imaginations and curiosities, and share them with the world. We are united by our need for safety, autonomy as beings, dissolution of trauma, and desire to ask, “What would happen if I…?” Imaginative, curious Women of Color (WoC)Footnote 1 founded the underground railroad, guided captured Africans and Tainos to the mountains, ignited the Civil Rights Movement, organized laborers and immigrants, birthed the #BlackLivesMatter Movement, conceived the #MeToo Movement, and so much more. Like our kindred counterparts, we have an unrelenting urge to examine, question, wonder, desire, speak to, lead, be curious, and “conjure.” As practicing artists and art educators, our critical arts-based practices are grounded in intersectional feminisms like Womanism, Black Feminist Theory, and Chicana Feminist Theory, which allow us to do these very things.Footnote 2

Critical arts-based practice is a research methodology that allows for evocative and critical engagement with and through intersections of aesthetics and historicized legacies of legalized, social and cultural oppressions (Wilson Reference Wilson2018). Practitioners of a critical arts-based inquiry (Wilson Reference Wilson2019; Wilson & Harris Reference Wilson and Lawton2019; Wilson Reference Wilson, Taylor, Ulmer and Hughesin press) draw from various arts disciplines (music, visual, performative, etc.) during all phases of social science research, including data collection, analysis, interpretation and representation. As art educators, we make sense of our world through aesthetic engagements, and as such find ourselves returning to our roots as visual artists. We see art-making as an extension of our pedagogy and as such, consider ourselves “liminal servants” (Garoian Reference Garoian1999, 43) whose responsibilities are the creation of educative and aesthetic entrances to emotional, spiritual and ephemeral spaces for ourselves and other WoC. We add to the existing arts-based methodological enactments by WoC art educators (Wilson Reference Wilson, Taylor, Ulmer and Hughesin press), whose work includes critical reflection and response to lived and embodied histories of the diaspora. We conjure by aesthetically representing our own musings, lived experiences and embodied histories, directly inspired by our engagement with the material and non-material world.

To these ends, critical arts-based inquiry has helped us find our center, our periphery, and our in-between spaces where we exist within and also beyond our earthly bodies that are policed day in and day out. Further, engaging in critical artmaking as a collective has allowed us to spiritually reconnect with lost experiences of consciousness, and hold each other down in the process. Further, with intersectional feminisms undergirding our work, we recognize the ways in which we theorize through our artmaking, thus countering “academic hegemony” (Christian Reference Christian1987, 53). We are interested in power, the power to come up with our own findings about what is salient in the experiences of WoC (Cooper Reference Cooper2015).

In essence, our work explores how we can make sense of Black and Brown subjectivities in/through the act of making. We ask: how might we aesthetically document the present by reflecting on the past, while in anticipation of unknown futures? To support and guide our critical arts-based practice, we first engaged in extended personal conversations in which we shared our minds’ vulnerable wanderings about the concept of “conjuring.” While many themes emerged throughout our dialogic engagements, three concepts were most prominent; memory, trauma, and joy. Therefore, we used critical arts-based practice as a “way-finding” tool to make sense of memory, trauma, and joy as WoC. In this paper, we 1) share brief summaries of our conversations that detail our understanding of the three essential themes that guided our artmaking, and 2) present the results of our visual “way-finding.” We conclude this paper with a brief discussion about the act of making and the gifts it provided us.

Memory

“What in the world do the experiences I have had actually mean? I've lived in the Gulf Coast, specifically Mobile, Alabama, which is where the last recorded slave ship illicitly transported African captives, and now I am here in Virginia where the first Africans were brought. And it has been a four-hundred-year span. And so, my life in these spaces has been literally bookended by these two moments. The first and the last.” —Gloria

Memory, the act of remembering, is vital to the human experience. Our brains encode, store and retrieve information as needed in the form of memories. We then utilize memories to inform future actions. Yet we know that memory lives not only in our minds, memory also lives in our bodies. Our conversation highlights the ways in which we seek to recall, remember, and reconnect - through our minds, bodies, family, sisterhood, water, art and music - to a larger (female) ancestral memory. We contemplate the circular, non-linear, complex nature of diasporic identities and experiences and the ways in which maternal lines physically, through the body, carry history, memory and ways of knowing. Our conversation began with us recalling our younger selves. Selves who we felt were free, soft and sensitive. Selves who instinctively remembered. Selves who live in the body of now, yet held the past and anticipate the future. We recognize the ways in which these selves endure through the desire to reconnect and remember. The body holds memory in its desire and erotic nature. The body remembers trauma and pain but also vividly remembers joy (Lorde Reference Lorde1984) and connection.

Trauma

“What is passed down through maternal lines and what happens when that line is severed?” —Vanessa

The body has a way of responding and holding on to distressing and disturbing experiences. Sharpe (Reference Sharpe2016) contends that the ocean and soil take up and hold memories of trauma (as in abandoned cargo of African bodies and remnants of lynchings). Our conversation reveals that we respond to and hold on to traumas in various ways, which has ultimately resulted in our on-going exhaustion. We recognize that we retreat during personal loss, are consumed by the exhaustion of code switching, carry guilt and heavy responsibility in mothering, feel the burdens of generational traumas, and question our responsibility in “holding court” with hegemonic masculinities.

We question how we as WoC might be consciously or unconsciously re-living these traumas, and perhaps, passing them on to others (children, colleagues, students). While navigating varied diasporic experiences (directly and indirectly), we acknowledge a historic memory that lingers, despite our attempts to protect ourselves from reminders (social and news media, for instance). In other words, our bodies are in constant f(l)ight mode.

Joy

“Joy is recognizing that we can exist outside of the violence that has been imposed upon our earthly bodies for centuries. We have a right to exist there.” —Joni

We crave joy. Unmediated, unabashed joy that we, WoC define, not others. Our conversation reveals that, for us, joy is significantly intertwined with the idea of “safety.” In our case, safety means not only protection from White hands that hold guns, batons, and pepper spray to harm our bodies, but safety from White minds and from White eyes. Unfortunately, in our past attempts at safety, we have resorted to running, both literally and metaphorically (Acuff, López & Wilson Reference Acuff, López and Wilson2019). We have had to “fold into ourselves,” avoid professional spaces and human interactions, even cross international waters, seeking ancestral guidance all in the name of finding joy. WoC should not be relegated to dark corners of a room, or dark corners of our minds in order to find safety, to find joy.

The potential to develop new ways of being seen and seeing ourselves excite us. We are exhausted from having to mediate our bodies and our minds for White acceptance. Further, understanding ourselves as WoC only in direct comparison to the dominant group is unfair, and violent. However, the clarity we gain from being tired, frustrated and enraged about White mediation can help us build joy (Cooper 2018). Cooper (2018) writes, “Joy arises from an internal clarity about our purpose” (274). As a collective of WoC in art education, our purpose in this White dominated field is to support each other's justice-oriented work, bolster one another up when we are worn, emotionally and psychologically, and praise the racial and ethnic nuances amongst us. Supporting each other in these ways brings us joy. We feel safety in one another, and thus, are joyous. This is an example of how joy can be simultaneously liberatory and an act of resistance.

Visual “Way-Finding”

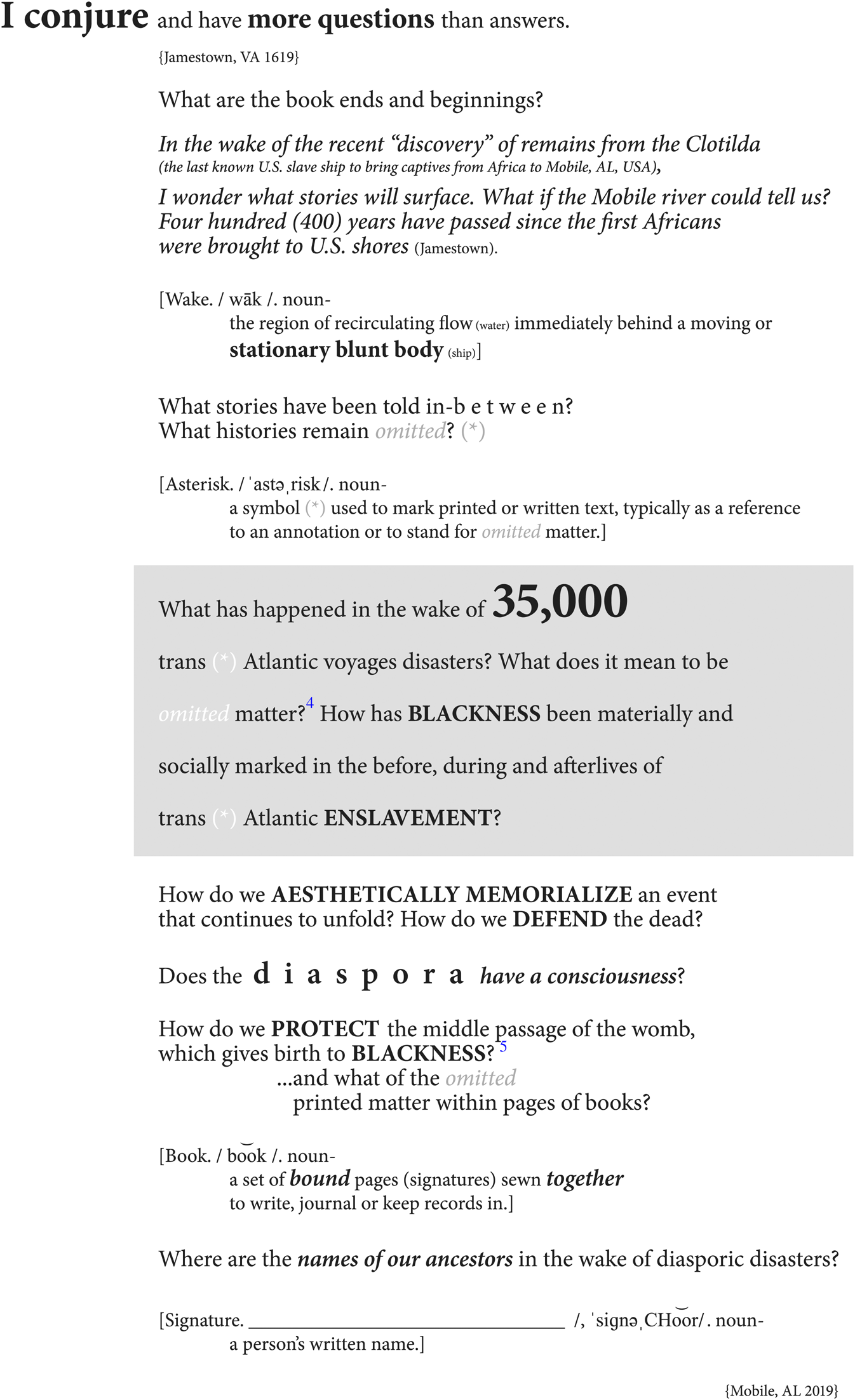

Gloria's Artwork and Artist Statement

Figure 1. Gloria J. Wilson. “In the Wake of Omissions and Inclusions.” 2019, Mixed media artist book (oxidized copper, leather, waxed linen thread, watercolor paper)

Joni's Artwork and Artist Statement

I forget the present. On earth, air can fill lungs and minds. The body wavers, moving fast, to nowhere. Toes stretched apart, grasping, clinching, trying with every bit of intention to hold the body steady on textured ground. The resistance is too hard, I tip, twistedly. Cumulus clouds, full with precipitation, catch me. As I lay, outstretched with my legs and arms spread apart like starfish, I feel nothing where a beating heart should be. It must be air there, too.

***

I remember the future. As I close my eyes really tight and sit in silence I can feel the cool and fast water rush over my caramel skin as the smell of fresh ocean life entertains my nostrils. I don't know where this place is, but my body is at home here, it belongs to this side of the earth, hot and wild, me. In this place, my melanin rich flesh is gritty sand, similar to that where my feet stand. In this place, my energy is divine and transcendent, it floats above earth. I sit and watch my earthly body “do what it do.” It has a womb, I call it “the sun.” Without it, earthly bodies cannot be. Like the starry, golden ball of fire in the heavens, my “sun” sustains life, life warm with blue blood and green veins, also of gritty sand, also of divine and transcendent energy. Duality.

***

I embody the past. Blood red dirt on tiny hands. Night sky mud pies on pursed lips. Rigged branches interlaced over head. Plush green grass between stubby toes. Snow white honeysuckle in nose. Knife sharp switches on butt. Juice filled blackberries on tongue. Redberry seeds in teeth. Honey-blond dog gone rabid. Up, then down, my Black body. Swinging brown legs from mature trees. Off-key singing from full belly. Grapefruit pink flesh exposed on dirty knee. Callused, heavy hands on fragile shoulders. Fresh cut grass in watery eyes. Fire red kisses tattooed on cold cheeks. Slick, warm bald head on hands. Virginia Slims smoke dances in air. Grown cursing tongues in young ears. Long, safe dirt road to home. Wide tire marks in pearl-gray gravel. Sharp, pointy rocks on orange heels. Decades old church hymns in mind. Contemplative walks to full mailbox. Salty, sticky sweat in damp clothes. Southern drawls in gossipy mouths. Consciousness.

Figure 2. Gloria J. Wilson. “In the Wake of Omissions and Inclusions.” 2019, Detail of inside cover and 1st page.

Figure 3. Gloria J. Wilson. “In the Wake of Omissions and Inclusions.” 2019, Detail of omitted/inserted pages.

Figure 4. Joni Boyd Acuff. “I am the Sun.” 2019, Mixed media (Found shoe horn, Acrylic paint, Pen, Muslin dyed with blueberries and hibiscus, honeysuckle branches, black thread, natural brown twine)

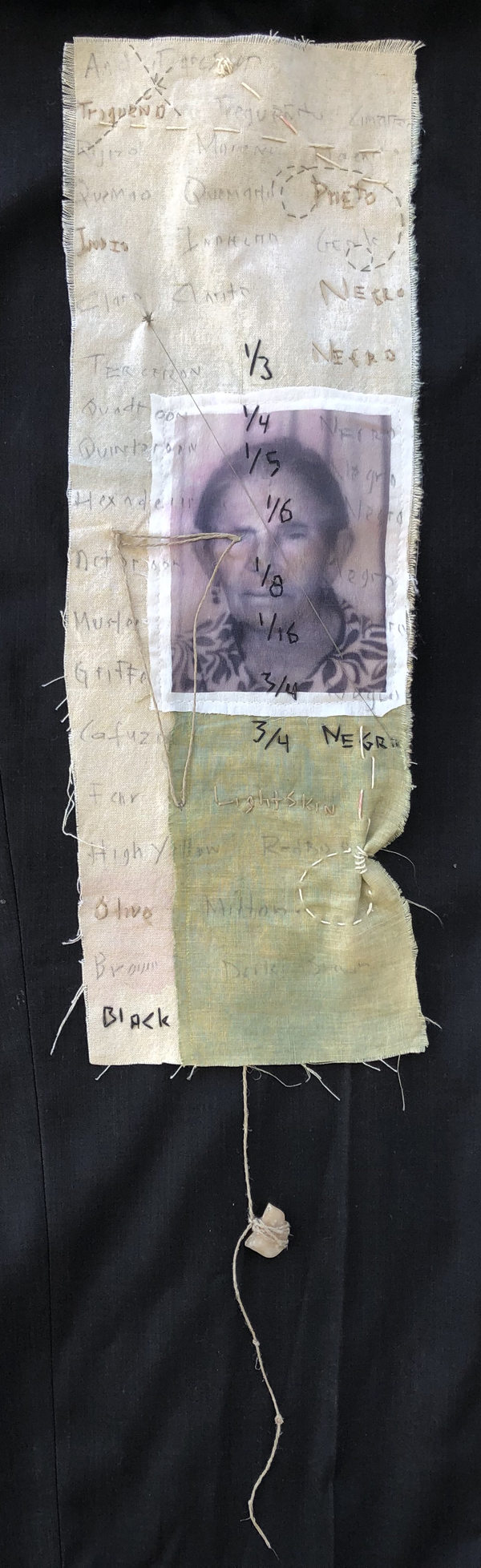

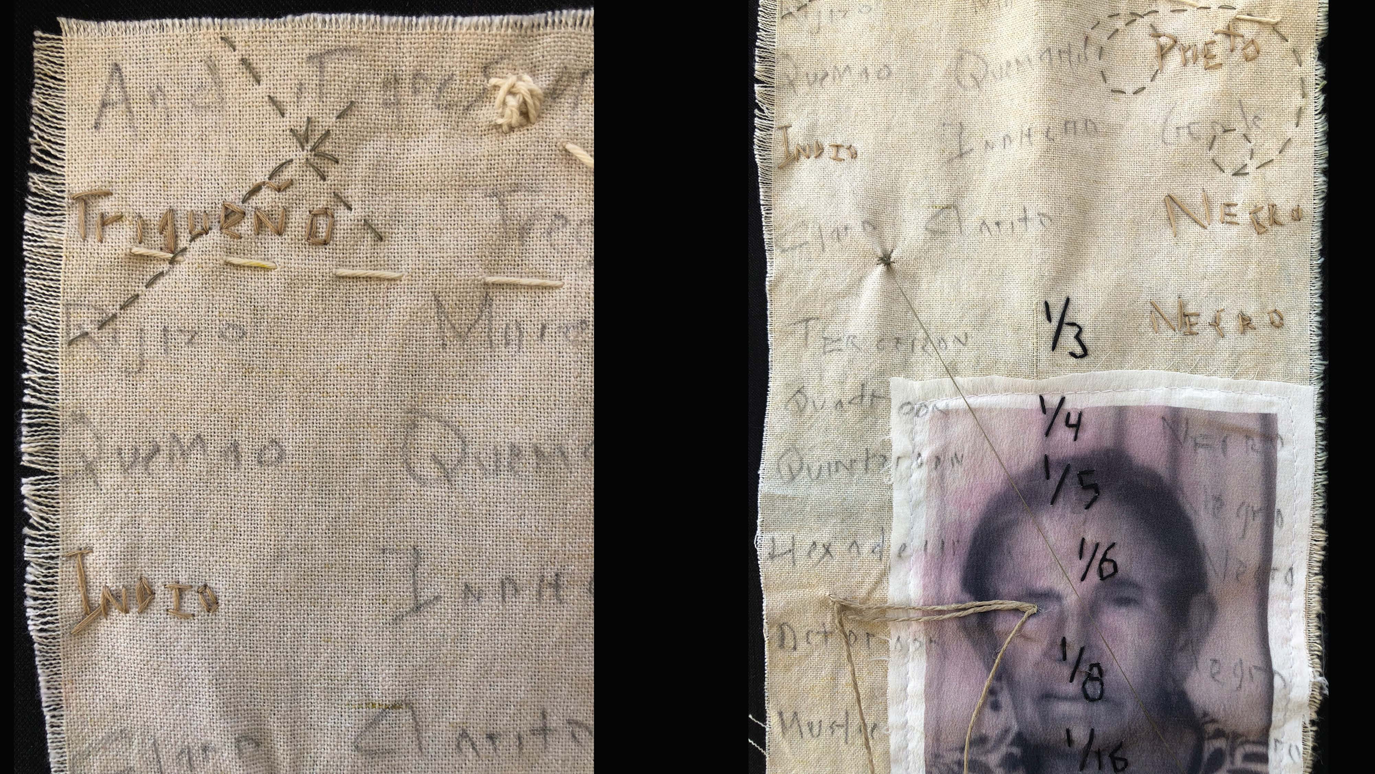

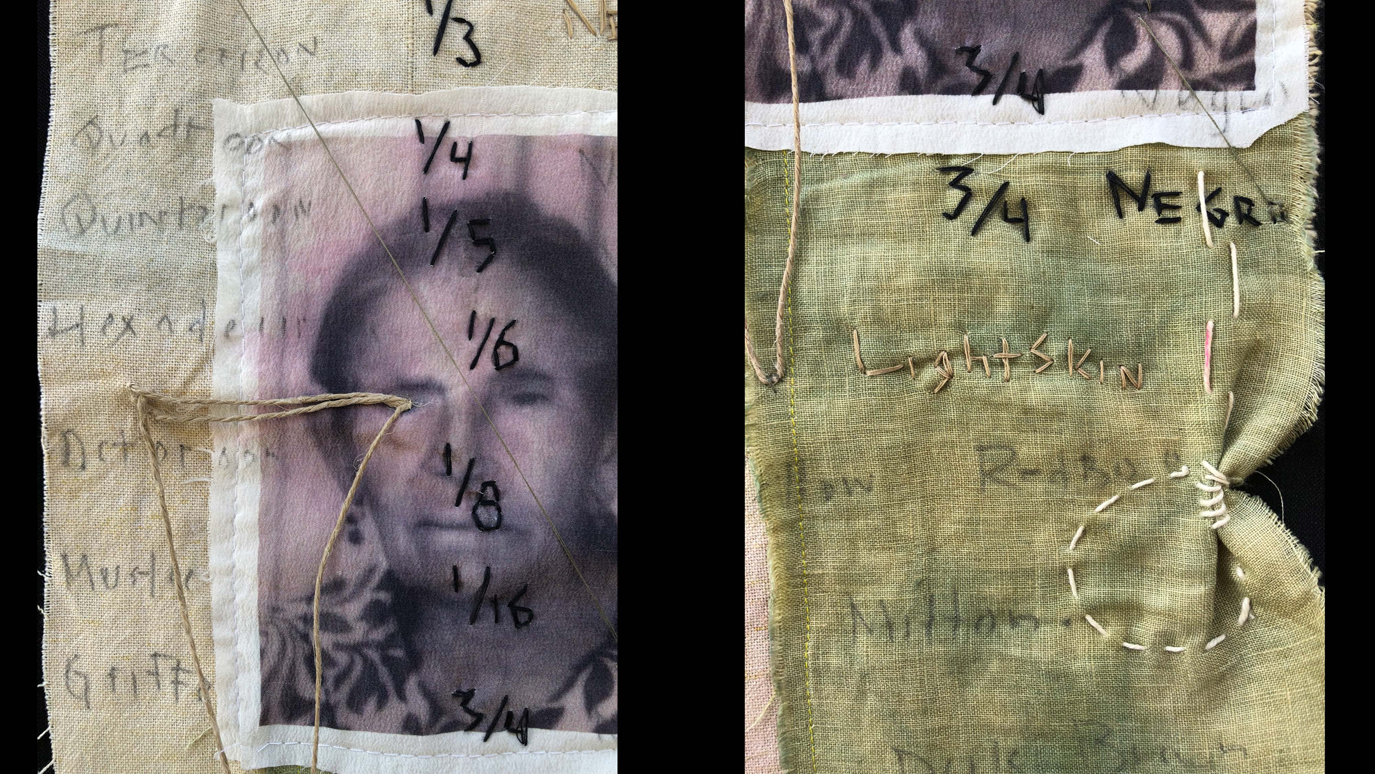

Vanessa's Artwork and Artist Statement

I remember feeling embarrassed of my mother's hands at parent teacher conference meetings.

Her hands exposed us.

Me.

That she worked too hard. That we were poor.

That her English was bad. That we were immigrants.

That I did not belong. Ni de aqui. Ni de alla.

I now adore her hands.

Trigueñito and spotted.

Hands that worked the land.

Hands that have travelled through time and space and land and water.

Hands that connect to the heart. Hands that know before the head can make sense of it all.

Hands that hold me together.

Hands that hold the history of conquest and rebellion and adaptation and resilience.

I now embrace the hand.

The work of the hand to dye the fabric from beige to black to brown to yellow to green.

The hand that pulls me apart and works to stitch/pull me back together.

The hand that creates connection.

To an old world. One where a small mulatto woman finds her way through colonization.

To create and stitch together a new clan - una nueva familia de negros, conquistadors, mulattos, indios, trigueñitos, claritos, mestizos.

To a new world. One where a rubia leaves her little island in search of something. More. To a new world full of dichotomies. With little room to breathe. And she too finds her way. Stitches together a life. With those hands. A life with concrete and cold and love and space to expand.

To now.

To stitching myself back together.

To her.

To here.

To now.

To free.

Figure 5. Joni Boyd Acuff. “I am the Sun.” 2019, Detail

Figure 6. Joni Boyd Acuff. “I am the Sun.” 2019, Detail

Discussion

As art educators, committed to our justice-oriented work, in response to historic marginalization, we necessarily centered the lens on ourselves, our lived experiences as WoC and our artmaking. Returning to our foundational training as visual artists allowed us to slip into familiar and unfamiliar artmaking processes, techniques and media. We used varied conceptual and tactile elements (color theory/symbolism, metals, fibers, found objects) in order to offer an aesthetic sensibility unique to visual arts communication. Our finished creations revealed that each of us was inspired by our immediate surroundings. Thus, our work was solidified not only by historical context but also by geo-spatial locations (i.e. homes and homelands). Paired with our impulse to create, these contexts helped us to make sense of our identities within the diaspora.

Figure 7. Vanessa López. “Everything but…”Footnote 3 2019. Mixed media (Naturally dyed fabric, scanned imagery, hemp, thread, pencil, stone), 8 x 24 inches

Our post-artmaking discussion further revealed how our in-depth exploration of the central themes (memory, trauma, and joy) conjured healing, self definition and expansion of self, and imagining beyond our current existence. For instance, Vanessa employed the restorative act of sewing as a metaphor for making connections among intergenerational maternal lineage, Gloria used oxidation processes on copper (patina) as a reference to the passage of time, to symbolize water and to draw attention to the healing properties of such a metal, and Joni embraced an evolution in her artmaking process by inviting a space to create alongside her children (as opposed to working in solitude or isolation). In what follows, we further detail each of the outcomes of our arts-based processes.

Figure 8. Vanessa López. “Everything but…” 2019, Detail

Figure 9. Vanessa López. “Everything but…” 2019, Detail

Creating as a Means of Healing

Through the process of writing and creating we strengthened our kinship ties (Acuff, López & Wilson Reference Acuff, López and Wilson2019; Wilson Reference Wilson2017) to each other and the greater African diaspora. As we reflected on this arts-based project, we agreed that our art-making allowed us to express our individual and collective remembrances of diasporic histories. These collective remembrances (which include individual memories), proved to be distinct while also proving to reach beyond a monolithic representation of diasporic identity. As result of slavery and colonialization, our pasts as people of color have been deliberately rubbed out and “our energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history” (Dery Reference Dery and Dery1994, 180). Therefore, the ability to (re)claim our individual and collective identities and connection to past, present and possible futures is an act of healing.

In various ways, we each expressed our reconnection to ancestral roots by working with and honoring our hands, our children, our chosen media/materials and processes. Further, we all agreed that our art work was heavily informed by the location of our bodies, with Brown skin and wombs, and with regards to geographical regions of the world. We reflected on our mothers’ wombs and on our own wombs, illustrating curiosities about the creation of life and beings. For us, remembering and reflecting constitute acts of healing. We were able to connect to and conjure stories that transcended our present traumas, like a diasporic umbilical cord that feeds, sustains and nourishes. Our creations also allowed us to occupy a metaphorical space of “forgetting,” (i.e. releasing ourselves from stagnant notions of identity) in order to liberate and heal ourselves from White patriarchal spaces. That is, in holding space for remembering and forgetting, we do not limit how our forward movements and/or how healing might occur. Remembering and forgetting was deeper than an intelletucal endeavor; remembering and forgetting was somatic, ancestral, erotic and sprirtual. In the words of M. Jaqui Alexander (2005), “we had forgotten that we had forgotten” (275). We forgot, in the exhaustion of day-to-day survival, that we could construct new whole selves, outside of Whiteness. Our creations, pieced together from the earthly and spiritual, made real through our own very hands, helped us remember our belonging.

Creating as a Means of Self Definition and Expansion of Self

Our musings and conjurings resulted in artworks in which we (re)visualized ourselves within various times and spaces. We asked: Who was I before this story I am currently living? Who am I here—in this place—now? How can I be all the things I am in this one body? Through the act of making we sought to literally (re)create ourselves—to make sense of the parts of our unknown history and the varied ways in which our stories have been rewritten and co-opted to benefit Whiteness, patriarchy and power. For example, in our post making discussion we all mentioned the ways in which, via the process of creating, we sought to reinterpret and expand definitions of self that we have imposed upon ourselves and/or have had imposed upon us, from recluse artist to artist-mother, from stranger-outsider to beloved-kin-family. Further, it was telling that even without discussing our plans for our individual works of art, all three of our artworks ended up being assemblages of mixed media. We assembled media, but we also (re)assembled our imaginations, our self definitions, and histories in an effort to make sense of our multidimensional worlds.

The act of creating has long been extolled as a means of self-expression and definition, but as WoC, the act of physically constructing a new self, made from our heads, our hands and our hearts, can be revolutionary. We need the time, space, and freedom to reconceptualize ourselves. To conjure. Black feminist theory supported our acts self definition, as the framework counters the negation and exclusion of Black women's experiences and our knowledge (Collins Reference Collins1990). Guided by intersectional feminists (Collins Reference Collins1990; Anzaldúa Reference Anzaldúa1997), we used our art to define ourselves, establish positive, multiple representations of ourselves, identify our cultural heritage as energy to resist daily discrimination, and confront interlocking structures of domination, such as race, gender, and class oppression (Acuff, Reference Acuff2018a). We were able to privilege our embodied ways of knowing.

Creating as Imagining Beyond Our Current Existence

Art making resulted in us being able to tap into and awaken dormant ancestral energy and consciousness that, as WoC, we are rarely able to engage with for many reasons. Tolle (as cited in Juline Reference Juline2019) writes, “In awakened doing there is complete internal alignment with the present moment and whatever you are doing right now. The doing is then not primarily a means to an end, but an opening for consciousness to come into this world” (para. 4). Critical art-based inquiry helped us explore our existence, “in the now,” both in our specific physical locations and in the intangible journeys within our minds. For example, in our post artmaking discussion, we acknowledged how we allowed our imaginations to wander outside of the limits of our initial sketches and conceptualizations of our art. We embraced the way material, people, family, and geographical location guided our minds and hands at the moment of creation. As WoC, our opportunities for being “present” and mindful are not bountiful, as we exist in protection mode most of the time, resulting in racial battle fatigue (Acuff, Reference Acuff2018b). Artmaking opened a portal in which we were able to engage in a world that did not depend on our current relationships with Whiteness, ridding us of stress and exhaustion. The works that we created are necessarily charged with and by our dedication to examine, elaborate, and ultimately emancipate ourselves from the racialized and gendered “mediation” we have experienced by societal norms and expectations (Moraga & Anzaldúa Reference Moraga and Anzaldúa2015).

As we made with our hands, we reflected and called upon maternal energies from our immediate bloodlines, on our African ancestors whose spirits are trapped on ocean floors, and on the earthly elements (i.e. land, trees, water) that inevitably will hold our remains one day (Sharpe, Reference Sharpe2016). Through our artmaking, we nurtured our relationship with the spiritual and natural world. We found that referencing earthly elements in our art supported our intention to see ourselves beyond our current existence, as a minoritized group in society. These materials supported our understanding that we are of the earth and are much larger than the narratives that have been imposed on our bodies.

In closing, we want to give thanks and express our gratitude to the Black and Brown women artists/creatives whose work we identify as conjurings. We have been inspired by the minds’ and hands of these WoC throughout our years of imagining and making with our hands. M. Jacqui Alexander, Janine Antoni, Gloria Anzaldúa, Firelei Báez, adrienne maree brown, Tina M. Campt, Ginetta E.B. Candelario, Elizabeth Catlett, Julie Dash, Cynthia Dillard, Jamea Richmond Edwards, Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Saidiya Hartman, Graciela Iturbide, Audre Lorde, Tamika Mallory, Santa Marta, Ana Mendieta, Trinh T. Min-Ha, Cherríe Moraga, Toni Morrison, Wangechi Mutu, M. NourbeSe Phillip, Howardena Pindell, Adrian Piper, María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Betye Saar, Lorna Simpson, Florinda Soriano “Mama Tingo,” Renee Stout, Luisah Teish, Christina Sharpe, Sonya Renee Taylor, Luisah Teish, Alma Thomas, Mickalene Thomas, Alice Walker, Kara Walker, Mami Wata, Carrie Mae Weems.

Acknowledgements

The author order does not represent the level of contribution. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of this paper equally from beginning to end. We emphasize the way we value process and equity, rather than a system of power. Specifically, we define “contribution” not only as pen to paper, or research hours, but as also emotional support to each other when needed, even for issues outside of this paper. Those lived experiences unequivocally contributed to this paper. The paper was produced over months of long girlfriend to girlfriend chats via video conferences, multiple manuscript read aloud sessions, late night and early morning text messages and, at times, some inappropriate, off topic voice messages. Thus, author order only represents the authors’ names, not their “contribution” to this work.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the love, support and kinship of crea+e (Coalition on Racial Equity in the Arts and Education).

gloria j. wilson, PhD is assistant professor of Art and Visual Culture Education at The University of Arizona. She is an artist, educator and public scholar whose work uses critical arts-based inquiry to examine the intersections of race, arts participation and equity in (arts) education. Her recent work uses a cultural studies lens to examine visual/popular culture as an informal curriculum and critical pedagogical tool in understanding the production and consumption of race/gender.

Joni Boyd Acuff, PhD is an artist, educator and pedagogical activist whose making, teaching, curriculum development and research explores the relationships amongst race, black womanhood and arts education in the US. Acuff is an associate professor in the Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy at The Ohio State University.

Vanessa López is Brave. Washington Heights. Sometimes artist. Always teacher. Latina. Angry af. Maryland Institute College of Art. 90s R&B. Mother. Bad and boujee. Dominican Republic. Published. Sexy. Rough around the edges. Connected. Tatted. Compassionate. Organic Intellectual. Four-minute planker. Ride-or-die b*tch. Wounded Healer. Role Model. Sometimes a rebel. Always a lady.