As evidence has accumulated regarding democratic backsliding, scholars of both comparative and American politics have turned their attention to scrutinizing the public's commitment to democracy and democratic norms. While it has been argued that the public's support for democracy is declining (Mounk, Reference Mounk2018), support for democracy from public surveys remains high, including in the US (Voeten, Reference Voeten2018). However, a growing body of evidence indicates these positive attitudes may be held less firmly than it seems. Along these lines, in this note we examine if a social norm to support democracy has led to an overestimate of positive attitudes toward democracy.

Although expressed support for democracy remains high, a substantial portion of the public expresses openness to “at least one nondemocratic approach—expert rule, autocracy, or military rule—as a good way to govern...” including “many in economically advanced nations”—this includes 53 percent in the United States (Wike and Fetterolf, Reference Wike and Fetterolf2018, 140). That is, there exists a portion of the public who could be termed “democrats in name only” in that they express support for democracy but also endorse processes incompatible with liberal democracy (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022, 426).

These observational findings are consistent with experimental evidence demonstrating the limits of the public's commitments to democratic norms. For example, partisans fail to punish their leaders for espousing undemocratic positions (Graham and Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020). Failure to punish co-partisans in power is particularly notable as voters’ knowledge of democratic norms was pre-tested. In short, partisans support their preferred parties despite the knowledge that their policies would undermine democracy (Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022) and may even be willing to compromise on the constitutional process underpinning a democracy if their supported leaders believe it is appropriate for political expediency (Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021). It has become increasingly clear that partisanship can trump support for democracy—a key component of which is accepting electoral outcomes, particularly when preferred parties or candidates face defeat. Elite rhetoric may play an important role in this regard: exposure to elite allegations of electoral irregularities may lead to public disillusionment with the process of transition of power in a democracy (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021).

Taken together, both survey and experimental findings suggest that public support for democracy is less firmly held than the existing literature supposed. An assumption that underlies much of this literature is that there exists a norm around expressing support for democracy (Svolik, Reference Svolik2019). If such a norm exists, this implies that responses to questions about democracy will be influenced by the presence of an interviewer as there is an expectation to express support for democracy.

It has long been recognized that characteristics of the survey process can influence responses (Deming, Reference Deming1944). Among these characteristics, the presence or absence of an interviewer has been identified as a source of variation in survey responses (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman1972). As such, the potential for survey mode effects was recognized since the advent of surveys administered over the internet (Joinson, Reference Joinson1999), confirmed by more recent evidence (e.g., Chang and Krosnick, Reference Chang and Krosnick2009).

If a particular response to a question is perceived as socially undesirable, a respondent may avoid being entirely honest when answering (Locander et al., Reference Locander, Sudman and Bradburn1976) as individuals engage, consciously or not, in a process of image management whereby they answer questions so as to present themselves in the most positive light (Millham and Kellogg, Reference Millham and Kellogg1980; Paulhus, Reference Paulhus1984). If respondents are less susceptible to the pressures that drive social desirability when surveys are self-administered, those interviewed via the internet will be more honest as the perceived cost of social sanctions is diminished. Social desirability effects are pervasive (Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski2000, ch. 9) and their relevance is well established for both political attitudes (e.g., Krysan, Reference Krysan1998) and behavior (e.g., Karp and Brockington, Reference Karp and Brockington2005). Different patterns of responses between internet and face-to-face surveys are similarly well documented—for example, levels of partisan acrimony are higher among respondents interviewed via the internet (Iyengar and Krupenkin, Reference Iyengar and Krupenkin2018).

We combine insights from the literatures on social desirability and support for democracy. We argue if it is the case that (1) there is a norm to support democracy and (2) that respondents feel freer to be honest in internet surveys then differences should emerge in reported satisfaction across survey mode. Specifically, we hypothesize that those interviewed in-person will express greater satisfaction with democracy. We test this hypothesis with surveys that are nearly identical with the exception of the mode of administration. We find support for our hypothesis and identify a politically relevant difference in self-reported satisfaction. We conclude that absent the possibility of an immediate social sanction, respondents report less satisfaction with democracy indicating a lower level of support than was often appreciated. Our result is robust to different measures and estimation strategies. Reassuringly we demonstrate that substantive relationships—we examine winner–loser status and satisfaction—are not necessarily altered by survey mode.

Our focus on satisfaction with democracy warrants some discussion as the ubiquitous satisfaction item does not directly tap the sort of illiberal attitudes associated with deconsolidation. While there exists disagreement among scholars as to what precisely the item measures, there is some degree of consensus: it is thought to be an intermediate-level variable for measuring political support, that lies between diffuse support variables such as regime-type preferences and specific support variables such as executive approval of an incumbent political leader (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Collins2020). Nevertheless, the lack of specificity in the question wording of the measure is an issue (Canache et al., Reference Canache, Mondak and Seligson2001). Literal interpretations of this measure run into problems arising from subjective evaluations of what democracy is, and its consistent evolution of what it has come to be at the time of research (Ferrin, Reference Ferrin2016). However, as indicated by Foa et al. (Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Collins2020), satisfaction with democracy reliably measures individual assessment of the democratic performance in the country. In this sense, satisfaction with democracy can be interpreted as an individual's assessment of the country's political system in their experience more than a generalized experience of democracy (Linde and Ekman, Reference Linde and Ekman2003) if not quite “ an expression of approval of the democratic process” (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012, 205). As a practical matter, the item is related to a host of relevant indicators, including satisfaction with democratic institutions (Lundmark et al., Reference Lundmark, Oscarsson and Weissenbilder2020) and the performance of democracy, including the rule of law and corruption (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Schneider and Halla2009). Thus, even if dissatisfaction is not synonymous with illiberalism, the item can be utilized to test our hypothesis of a norm to express support for democracy.

1. Data

We utilize the 2012 and 2016 American National Election Studies (ANES) conducted by the Center for Political Studies (CPS). In each year, the CPS obtained two separate nationally representative samples—one of which was conducted with face-to-face interviewers (FTF) and another over the internet. In 2012, 3567 respondents (65 percent of the total) who completed both the pre- and post-wave surveys were interviewed by internet compared to 1880 who were interviewed FTF. In 2016, 2566 respondents (71 percent) were interviewed over the internet compared to 1040 FTF respondents. While different sampling techniques were used to obtain the samples (e.g., cluster sampling was used for the FTF interviews), this does not necessarily pose an issue for our purposes. We acknowledge that a research design in which mode was randomly assigned after respondents agreed to be interviewed is necessary to obtain a clean causal estimate of mode on satisfaction (Gooch and Vavreck, Reference Gooch and Vavreck2019). While we cannot treat survey mode as truly random, we may be able to treat mode “as if” randomly administered (Dunning, Reference Dunning2008) allowing us to estimate the impact of mode—and thus, social desirability—on self-reported satisfaction.

We scrutinize the appropriateness of the assumption of “as if” random assignment by examining if demographic differences exist across modes, perhaps resulting from different patterns of response rates. This is essential as it has been argued that studies of mode effects may be conflated with other aspects of the survey process such as “sampling method, response rates, or sampling frame” (Gooch and Vavreck Reference Gooch and Vavreck2019, 144). Indeed, in both years, there are slight sampling frame differences as the FTF sample only includes respondents from the 48 contiguous states and Washington D.C. However, only 0.23 percent of respondents are from Hawaii and Alaska and as such the decision to include them does not alter the results we present. A larger issue is that the 2012 FTF sample included an over-sample of Black and Latino Americans.Footnote 1 We address this issue by utilizing survey weights and, as we discuss in more detail momentarily, by adjusting for a set of demographic covariates, including race, potentially related to survey mode. While we utilize the survey weights provided by the CPS in each of our analyses, this decision does not drive our results.

To examine if there are any demographic imbalances across the two samples, we estimate a model where the dependent variable is survey mode. We include age, income, sex, marital status, education, race, and Census Bureau region; coding instructions for each variable are included in the supplementary material (Appendix A). None of the demographic variables are associated with survey mode at the 5 percent significance level in either year.Footnote 2 Full results of the balance tests are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix B). While we observe balance between the samples, we estimate the relationship between mode and satisfaction while adjusting demographic covariates as we cannot treat mode as truly random; moreover, doing so increases the precision of the estimated relationship. We avoid including any variables that themselves may be influenced by mode.

As noted, we utilize the standard satisfaction item in which respondents are asked, “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in the United States?” While it is argued the measure “gauges people's responses to the process of democratic governance” (Anderson, Reference Anderson1998, 584) and can “be thought of as more concrete than measures that tap citizens’ views of democratic principles but as more diffuse than evaluations about the government in place” (Nadeau et al., Reference Nadeau, Daoust and Dassonneville2021, 6), we investigate the robustness of our results using two related attitudes—outlined later—given conceptual ambiguity discussed earlier. We initially examine the effect of mode by dichotomizing the satisfaction item so that all those who reported being at least somewhat satisfied as one and all others as zero. We test the robustness of our results by utilizing the original four-category coding (coded so that larger values represent greater satisfaction).

2. Results

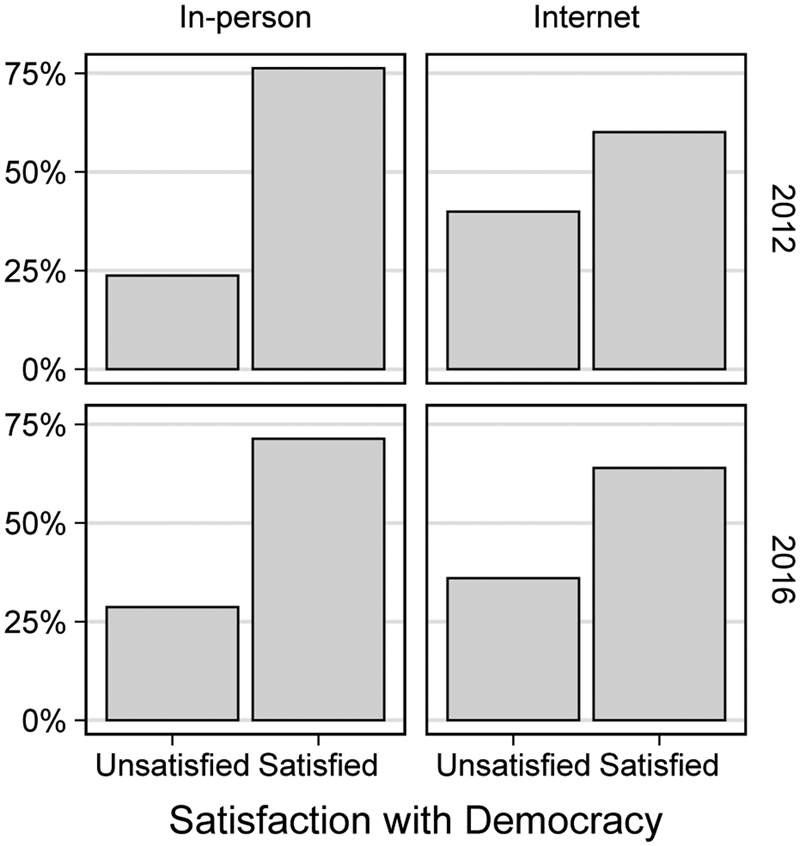

We begin by presenting the distribution of satisfaction conditioned on survey mode in Figure 1, where the satisfaction measure is coded dichotomously.Footnote 3 The columns represent survey mode, while each row presents the data for a particular year. The gap between the percent who are satisfied and unsatisfied is noticeably smaller in the internet sample in both years. For example, in 2016 the gap is 35 percentage points in the FTF sample compared to 28 percentage points in the internet sample.

Figure 1. Satisfaction with democracy conditioned on survey mode. Satisfaction is measured dichotomously—the precent satisfied represents those who are at least “somewhat satisfied” with democracy.

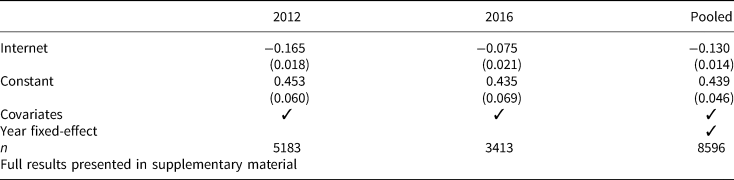

We estimate a linear regression model with a dummy variable representing survey mode to estimate the effect of mode on self-reported satisfaction. We code those interviewed by internet as one and those interviewed FTF as zero. A negative coefficient therefore indicates a lower likelihood of being satisfied among internet respondents. We present results for each year separately as well as for a pooled model. The result of interest, the coefficient for mode, is presented in Table 1. Full results are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix B). In 2012, being interviewed in person increases the probability of being at least somewhat satisfied by 16.5 percentage points (p < 0.001) and in 2016 by 7.5 percentage points (p < 0.001). This shift is similar in magnitude to known sources of satisfaction, including winner–loser status (e.g., Bernauer and Vatter, Reference Bernauer and Vatter2012; Halliez and Thornton, Reference Halliez and Thornton2022,5). Models estimated with logistic regression—presented in the supplementary material (Appendix C)—return identical results.

Table 1. The relationship between survey mode and satisfaction with democracy

The different sampling frames used for the two samples in each year do not influence our results. Models excluding respondents from Alaska and Hawaii return identical coefficients to those in Table 1. Full results are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix D).

Given the oversampling in the 2012 FTF sample discussed earlier, we assess if the decision to utilize survey weights is driving our results. We unsurprisingly identify demographic differences across the two modes when we examine the 2012 data without weights. When we estimate the relationship between survey mode and satisfaction while adjusting for demographic characteristics without weights, the estimated coefficient is quite similar to those reported in the first column in Table 1: −0.153 (p < 0.001). A model without weights using the 2016 data returns a coefficient of −0.071 (p < 0.001). Full results of these analyses are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix E).

We further examine the robustness of our main result by retaining the original four category coding of satisfaction. We again observe a meaningful shift as a result of survey mode. Being interviewed via the internet leads to a decline of 0.244 (p < 0.001) in 2012 and 0.130 (p < 0.001) in 2016. Further, our substantive conclusions remain the same when explicitly taking the ordered nature of the satisfaction item into account. Full results of each of these analyses are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix F).

Finally, our main analyses did not adjust for partisanship, ideological self-identification, or vote choice, as each variable itself might be driven by survey mode. Reassuringly, we observe balance for each of these three variables across the samples in either year. Further, results from models that adjust for all three return similar results: the coefficient for mode is −0.147 (p < 0.000) in 2012, −0.084 (p = 0.001) in 2016, and −0.120 (p < 0.001) in a pooled model. Full results are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix G).

3. Extensions

Here we extend our analysis in two ways. First, we estimate models with alternative measures of attitudes about democracy. Second, we examine if the relationship between winner–loser status and satisfaction varies by mode.

3.1 Alternative measures of democratic attitudes

Given the ambiguity as to what precisely the satisfaction item measures, we examine if our result extends to other indicators tapping democratic goodwill. Lamentably, the ANES does not include measures of illiberal attitudes in either year. We are, however, able to examine political trust and efficacy. Political trust is a dichotomous measure of if the respondent thinks the federal government is run for the benefits of a few, or for all; efficacy is measured using a two-item scale.Footnote 4 Coding details are included in the supplementary material. As before, we estimate the model in each year as well as in a pooled model. Survey mode is related to both attitudes: those interviewed by the internet report lower levels of trust and less belief that their vote matters. We present results of these analyses in the supplementary material (Appendix I). While this analysis increases confidence that our results are not limited to the quirks of the satisfaction question, future research should more thoroughly examine mode effects on items more directly linked to illiberal attitudes—for example, support for military takeover or the preference for a less constrained executive.

3.2 Does the winner–loser satisfaction gap vary by mode?

If survey mode influences satisfaction, it is possible that it also influences the substantive relationship between it and known predictors. To assess this possibility, we examine if the well-established winner–loser relationship satisfaction varies by mode. To do so, we estimate a standard model of satisfaction examining the relationship between winner–loser status (coded by presidential vote) and satisfaction where we interact winner–loser status with mode. We control for interest, perceptions of the economy, ideology, income, education, and gender (coding instructions are presented in the supplementary material).

A significant coefficient for the interaction term would indicate the relationship varies by mode. Reassuringly, we fail to reject the null hypothesis in both years (p2012 = 0.724; p2016 = 0.430) and with a pooled model (p = 0.663). Full results are presented in the supplementary material (Appendix H). While it is worthwhile to further investigate if well-established relationships vary by mode, these results suggest scholars are on reasonably firm ground when examining substantive determinants of satisfaction no matter the mode.

4. Conclusion

Across different measurement and estimation strategies, we identify a meaningful difference in self-reported satisfaction with democracy between those interviewed face-to-face compared to over the internet. Respondents’ expressed attitudes about democracy are influenced by the presence of an in-person interviewer suggesting there exists a norm to support democracy. Consequently, existing estimates of the public's satisfaction with democracy may be biased upward when relying on in-person samples. With that said, we stress that even internet respondents are, on average, satisfied with democracy. We also demonstrated that our result extends to two other items tapping attitudes toward democracy, political trust, and efficacy. While survey mode influences levels of satisfaction, a subsequent analysis demonstrated that reassuringly substantive relationships are not necessarily altered by mode—the relationship between winner–loser status and satisfaction is similar across both FTF and internet samples.

As scholars have charted the global retreat of democracy over the last several decades, attention has also turned to the public's commitment to democracy. While our results do not speak directly to issues of democratic consolidation or backsliding, our results indicate that expressed support for such institutional regimes is influenced by the manner in which such attitudes are measured. In particular, measures tapping public support of democracy conducted using in-person interviews may be prone to overestimation due to perceived social sanctions and “social image” issues. That is, a portion of the public has internalized the norm that democracy is “good” but it is less clear what precisely their expressed support entails.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2023.32. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HNYJTA.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Shane Singh for helpful feedback.