Lithium is a well-established and highly effective treatment for patients with bipolar disorder. Lithium use has steadily declined since the early 1990s, partly because newer, branded, alternative treatments became available. Reference Coryell1–Reference Young and Hammond3 Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) is an enzyme with a multitude of effects on neurotrophic response, autophagy, oxidative stress, inflammation and mitochondrial function, and it has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's disease. Reference Forlenza, De-Paula and Diniz4 Lithium inhibits GSK3 and has been hypothesised to protect against the development of Alzheimer's disease, which is the most common cause of dementia. Reference Klein and Melton5,Reference Phiel, Wilson, Lee and Klein6 Empirical evidence regarding the hypothesised protective effect has been promising but mixed. Reference Forlenza, de Paula, Machado-Vieira, Diniz and Gattaz7 After small observational studies in the mid-2000s produced contradictory findings, Reference Dunn, Holmes and Mullee8,Reference Nunes, Forlenza and Gattaz9 reports from a large Danish population-based registry data-set reported a significant protective effect of lithium against dementia. Reference Kessing, Forman and Andersen10,Reference Kessing, Sondergard, Forman and Andersen11 Two studies, the first inclusive of all patients prescribed lithium in Denmark, the other restricted to the subset with psychiatric hospital services for bipolar disorder, reported strong protective effects (as large as a 62% reduction in relative risk) of continued lithium use among lithium users. Two randomised controlled trials of adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease did not observe a protective lithium effect, Reference Hampel, Ewers, Burger, Annas, Mortberg and Bogstedt12,Reference Macdonald, Briggs, Poppe, Higgins, Velayudhan and Lovestone13 whereas another trial in participants with mild cognitive impairment but without manifest Alzheimer's disease reported significant protective effects on biomarker (cerebrospinal fluid phosphorylated tau (CSF P-tau)) and cognitive outcomes, Reference Forlenza, Diniz, Radanovic, Santos, Talib and Gattaz14 suggesting that lithium's neuroprotective effects may be limited to very early stage Alzheimer's disease. Notably, the positive clinical trial examined lithium exposure of 12 months' duration and the authors argued that longer-term exposure may be necessary to demonstrate a protective effect of lithium. Reference Forlenza, Diniz, Radanovic, Santos, Talib and Gattaz14 Another recent, small, randomised controlled trial reported that lithium at extremely low doses (300 μg once daily) Reference Nunes, Viel and Buck15 was efficacious in preventing cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease, a key finding given concerns regarding lithium toxicity in elderly patients at standard doses. Reference Sproule, Hardy and Shulman16 The present observational study examines the association of lithium therapy and dementia risk in the largest and most diverse data-set of older adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder to date. We hypothesised that continuous but not sporadic or intermediate treatment with lithium would be associated with reduced dementia risk, whereas exposure to anticonvulsants (a negative control) would show no association at any level of exposure.

Method

We conducted a retrospective, population-based, observational cohort study among people ≥50 years of age who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. As bipolar disorder has been linked with increased dementia risk and lithium is predominantly used to treat bipolar disorder, we restricted the study population to those diagnosed with bipolar disorder to reduce confounding by indication. Reference Kessing and Nilsson17–Reference Kessing, Olsen, Mortensen and Andersen19

Data sources and study cohort

Our study used combined service and pharmacy claims (Medicaid Analytic Extract, Medicare Parts A and B) from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2004 from eight large US states (California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Texas). These data include over 44 million individuals and represent approximately 40% of the Medicaid insured US population. Medicaid is a social healthcare programme for US residents with low incomes or various disabilities. Because Medicare is the primary payer for physician and hospital services for most individuals ages ≥65 years in the USA, Medicare Part A and B data were matched for all Medicaid insured individuals who were dually eligible for Medicare. People entered the study upon meeting the following criteria at the index date: (a) continuous Medicaid eligibility during the previous 395 days, (b) a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (one in-patient or two out-patient claims with ICD-9-CM codes 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x in any position) 20 during the pre-index period, and (c) age ≥50 years. Because our lithium exposure definition is calculated based on the medication supply during the preceding 365 days, we required a 395-day period of prior eligibility to facilitate the calculation of exposure from day 1 of follow-up (365 days plus 30 days to capture prescription claims in the month prior to the 1-year exposure period). Patients with a diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (any claim with ICD-9-CM 290.0x-290.4x, 294.1x, 331.0x, 331.1x-331.2x, 331.82-3, 331.9x), treatment for dementia (any prescription claim for donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine or memantine) or a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychoses (any claim with ICD-9-CM 295.xx, 290.8x, 290.9x, 297.xx-299.xx, 780.1x) during the 12-month pre-index period were excluded.

Exposure and outcome

Lithium was the primary exposure. Because the hypothesised protective effects require prolonged exposure, we examined cumulative exposure over a 1-year period. Specifically, exposure to lithium was defined time-dependently for each day of follow-up as the cumulative number of days of medication supply over the previous 365 days in 4 categories: none (0 days), sporadic (1–60 days), intermittent (61–300 days) and continuous (301–365 days). Anticonvulsants that may be used in this population as mood stabilisers served as a negative control and were operationalised in a manner analogous to lithium (online Table DS1).

Anticonvulsants were selected as a negative control because among available pharmacological treatments for bipolar disorder (i.e. lithium, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics), anticonvulsants are most comparable with lithium in anti-manic and antidepressant properties, Reference Ernst and Goldberg21,Reference Nemeroff22 thus reducing the potential for confounding. Reference Setoguchi and Gerhard23 Study outcome was incident dementia, defined as one in-patient or two out-patient claims for any listed ICD-9-CM diagnosis of 290.0x-290.4x, 294.1x, 331.0x, 331.1x-331.2x, 331.82, 331.9x. Reference Hebert, McBean, O'Connor, Frank, Good and Maciejewski24 Medicare claims have been found to demonstrate 61% sensitivity and 82% specificity compared with expert panel diagnoses of dementia. Reference Gruber-Baldini, Stuart, Zuckerman, Hsu, Boockvar and Zimmerman25

Covariates

Demographic variables included age, gender, ethnicity and reason for Medicaid eligibility (disability, poverty, other). In addition, we included residency in a long-term care facility, psychiatric comorbidity (depression, anxiety, alcohol-related, and drug-related disorders), cardiovascular comorbidity (arrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, other acute ischemic heart disease, other chronic ischemic heart disease, and hypertension), cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and Parkinson's disease (online Table DS2). Medication classes included antidepressants, antipsychotics and anti-anxiety medications (online Table DS1).

Statistical analysis

We calculated sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at baseline for the full cohort and stratified by use of lithium and anticonvulsants at any point during the study period. We then calculated event rates and 95% confidence intervals for the full cohort as well as for non-use (referent), sporadic use, intermediate use, and continuous use of lithium and anticonvulsants. Cox proportional hazard models with time-dependent exposure were then fit to estimate the hazard ratios for prior year exposure (sporadic use, intermediate use and continuous use) to (a) lithium and (b) anticonvulsants (negative control) compared with non-use. Follow-up began on the index date and ended at loss of service eligibility, death, end of the study period or occurrence of the study outcome, whichever came first. We fit an unadjusted model; a model adjusted for gender, age and ethnicity; and a fully adjusted model. The fully adjusted model controlled for all covariates presented in online supplement DS1. Age was categorised into 5-year age bands beginning with age 50–54. Age categories and medication treatments for bipolar disorder were included as time-dependent variables and updated for each day of follow-up.

Results

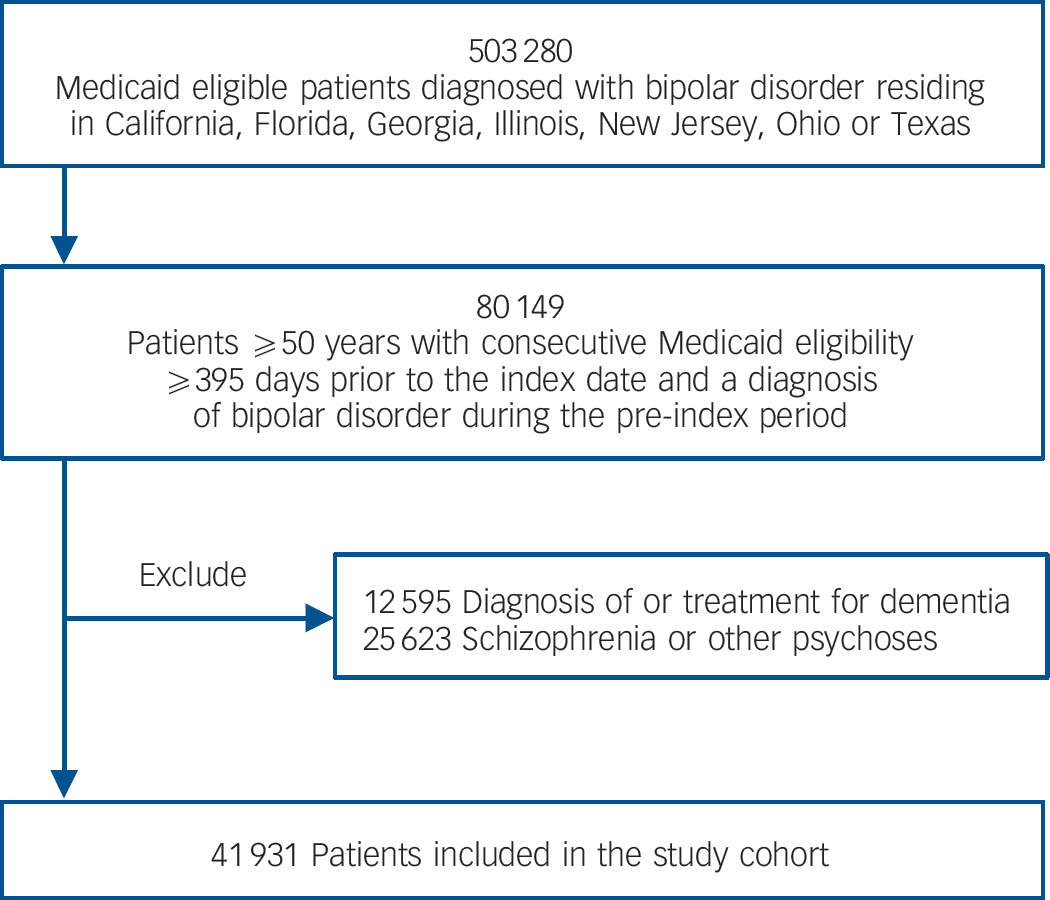

The study cohort included 41 931 people ≥50 years of age who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Figure 1 depicts the cohort assembly process. The cohort was predominantly female and White with a mean age of 60.4 years at index date. Three-quarters were eligible for Medicaid through disability and 18% resided in long-term care. Table 1 presents detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort overall and stratified by exposure to lithium and to anticonvulsants at any point over follow-up.

Fig. 1 Assembly of the study cohort.

Table 1 Selected demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder a

| Full cohort (n = 41 931) |

Lithium

b

(n = 6900) c |

Anticonvulsants

b

(n = 20 778) c |

No lithium or anti-convulsant b (n = 18 119) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 11 973 (28.6) | 2 004 (29.0) | 5 647 (27.2) | 5 402 (29.8) |

| Age, mean (s.d.) | 60.4 (9.9) | 59.0 (8.5) | 59.2 (8.8) | 61.9 (11.0) |

| Race ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 27 853 (66.4) | 4 778 (69.3) | 14 173 (68.2) | 11 657 (64.3) |

| African American | 4 697 (11.2) | 491 (7.1) | 1 990 (9.6) | 2 469 (13.6) |

| Hispanic | 3 276 (7.8) | 458 (6.6) | 1 519 (7.3) | 1 541 (8.5) |

| Other | 6 105 (14.6) | 1 173 (17.0) | 3 096 (14.9) | 2 452 (13.5) |

| Medicaid eligibility, n (%) | ||||

| Disability | 32 202 (76.8) | 5 727 (83.0) | 16 989 (81.8) | 12 795 (70.6) |

| Poverty | 8 596 (20.5) | 1 005 (14.6) | 3 274 (15.8) | 4 781 (26.4) |

| Other | 1 133 (2.7) | 168 (2.4) | 515 (2.5) | 543 (3.0) |

| Long-term care, n (%) | 7 381 (17.6) | 801 (11.6) | 3 384 (16.3) | 3 672 (20.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Depression | 15 451 (36.8) | 1 955 (28.3) | 7 846 (37.8) | 6 886 (38.0) |

| Anxiety | 5 841 (13.9) | 648 (9.4) | 2 844 (13.7) | 2 772 (15.3) |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 2 668 (6.4) | 359 (5.2) | 1 410 (6.8) | 1 146 (6.3) |

| Substance-related disorders | 4 806 (11.5) | 622 (9.0) | 2 481 (11.9) | 2 112 (11.7) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Arrhythmias | 3 422 (8.2) | 425 (6.2) | 1 587 (7.6) | 1 664 (9.2) |

| Heart failure | 4 611 (11.0) | 436 (6.3) | 2 172 (10.5) | 2 259 (12.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 447 (3.5) | 153 (2.2) | 663 (3.2) | 728 (4.0) |

| Other acute ischemic heart disease | 3 111 (7.4) | 358 (5.2) | 1 511 (7.3) | 1 458 (8.1) |

| Other chronic ischemic heart disease | 6 233 (14.9) | 679 (9.8) | 2 896 (13.9) | 3 042 (16.8) |

| Hypertension | 18 548 (44.2) | 2 427 (35.2) | 8 950 (43.1) | 8 570 (47.3) |

| Other comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4 218 (10.1) | 458 (6.6) | 2 028 (9.8) | 2 014 (11.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 226 (24.4) | 1 382 (20.0) | 5 091 (24.5) | 4 568 (25.2) |

| Parkinson's disease | 1 096 (2.6) | 170 (2.5) | 548 (2.6) | 483 (2.7) |

| Psychotropic medications, b n (%) | ||||

| Antidepressants | 27 201 (64.9) | 4 383 (63.5) | 15 183 (73.1) | 10 349 (57.1) |

| Antipsychotics | 22 478 (53.6) | 4 411 (63.9) | 13 052 (62.8) | 7 654 (42.2) |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 20 743 (49.5) | 3 581 (51.9) | 11 901 (57.3) | 7 572 (41.8) |

a. Data from eight states of Medicaid claims.

b. At any point during the study period.

c. Not mutually exclusive.

Compared with non-users of any mood stabilisers, lithium users were younger, less likely to reside in long-term care or have diagnosed psychiatric, cardiovascular or other somatic comorbidities, and more likely to receive other classes of psychotropic medications. Characteristics of users of anticonvulsants generally fell between those of lithium users and mood stabiliser non-users. Alcohol and substance-related disorders, and use of antidepressants or anxiolytics/hypnotics, were more common in users of anticonvulsants than in the other two groups.

The study cohort accrued a total of 66 258 person-years of follow-up (mean follow-up of 19 months). End of study period was the most common reason for censoring followed by loss of Medicaid eligibility and death (online Table DS3). Lithium use was observed in 6900 patients, who contributed 12 748 person years of follow-up. There were 20 778 patients with one or more prescription fills for anticonvulsants, with a total of 35 221 exposed person years. In total, 3866 patients were exposed to both lithium and anticonvulsants over the course of follow-up. For both lithium and the anticonvulsants, intermittent exposure was most common, followed by continuous and sporadic exposure (Table 2). A total of 18 119 patients were not exposed to either lithium or any of the study anticonvulsants at any point during follow-up. Members of the study cohort commonly filled one or more prescriptions for other psychotropic medications including antidepressants (64.9%), antipsychotics (53.6%) and anxiolytics (49.5%) at some point during the study period (Table 1).

Table 2 Dementia diagnosis during follow-up period for baseline cohort of patients with bipolar disorder a

| n b | Person-years | Event | Incidence rate (95% CI) c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full cohort | 41 931 | 66 258 | 1 538 | 2.32 (2.21–2.44) |

| Lithium, cumulative exposure d | ||||

| 0 day | 37 485 | 56 164 | 1 377 | 2.45 (2.32–2.58) |

| 1–60 days | 2 925 | 990 | 18 | 1.82 (0.98–2.66) |

| 61–300 days | 4 808 | 4 460 | 79 | 1.77 (1.38–2.16) |

| 301–365 days | 3 766 | 4 644 | 64 | 1.38 (1.04–1.72) |

| Anticonvulsants, cumulative exposured | ||||

| 0 day | 28 046 | 37 656 | 925 | 2.46 (2.30–2.61) |

| 1–60 days | 8 604 | 3 344 | 78 | 2.33 (1.82–2.85) |

| 61–300 days | 13 920 | 12 114 | 251 | 2.07 (1.82–2.33) |

| 301–365 days | 11 014 | 13 145 | 284 | 2.16 (1.91–2.41) |

a. Data from eight states of Medicaid claims.

b. Not mutually exclusive. As a result of the time-dependent specification of exposure, one individual can appear in multiple exposure categories.

c. Rate expressed per 100 person-years.

d. Cumulative exposure in past 365 days for each day in the follow-up period beginning on the index date and ending at end of study period, occurrence of outcome, death or loss of eligibility, whichever comes first.

There were 1538 individuals (3.7%) newly diagnosed with dementia during follow-up (2.32 cases per 100 patient-years). Table 2 displays unadjusted incidence rates stratified by cumulative past-year exposure to lithium and anticonvulsants. The numerator is the number of newly diagnosed cases of dementia; the denominator is the person-time at risk. Compared with lithium non-use, increasing duration of lithium exposure in the past year was associated with a continuing decrease in the unadjusted incidence rate of dementia. A similar, but much less pronounced, decrease was observed for the anticonvulsants. Results of the time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models (unadjusted; gender, age, ethnicity adjusted; fully adjusted) are presented in Table 3. In the fully adjusted model, continuous (301–365 days; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.77, 95% CI 0.60–0.99) but not intermediate (61–300 days; HR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.83–1.31) or sporadic (1–60 days; HR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.67–1.71) exposure to lithium compared with lithium non-use (0 days of exposure in the preceding 365 days) was associated with a significant decrease in dementia risk. For the anticonvulsants, none of the exposure categories were significantly associated with dementia risk. Among the covariates, age was the strongest predictor of dementia ranging from HR = 1.72, 95% CI 1.32–2.23 for age 55–59 to HR = 19.07, 13.54–26.87 for age 90+ (referent age category: 50–54). Male gender, Black ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility through poverty, long-term care residency, depression, alcohol-related disorders, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and Parkinson's disease were also significant predictors of dementia (data not shown).

Table 3 Risk of Dementia in patients with bipolar disorder by cumulative exposure to lithium and anticonvulsants a

| HR (95% CI), unadjusted | HR (95% CI), gender, age, ethnicity adjusted | HR (95% CI), fully adjusted b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative 365 day exposure | Lithium | Anticonvulsants | Lithium | Anticonvulsants | Lithium | Anticonvulsants |

| 0 days (referent) (non-use) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1–60 days (sporadic) | 0.74 (0.47–1.18) | 0.95 (0.76–1.20) | 1.16 (0.73–1.86) | 1.42 (1.13–1.79) | 1.07 (0.67–1.71) | 1.26 (0.99–1.60) |

| 61–300 days (intermittent) | 0.72 (0.58–0.91) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | 1.24 (1.08–1.43) | 1.04 (0.83–1.31) | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) |

| 301–365 days (continuous) | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) | 0.88 (0.77–1.01) | 0.70 (0.54–0.90) | 1.13 (0.99–1.30) | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) |

a. Data from eight states of Medicaid claims. Results presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

b. The fully adjusted model includes the following covariates: gender, ethnicity (Black, White, Hispanic, other), age (time-dependent, years, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90+), Medicaid eligibility (disability, poverty, other), long-term care residency, depression, anxiety, alcohol-related disorders, drug-related disorders, arrhythmia, heart failure, myocardial infarction, other acute ischemic heart disease, other chronic ischemic heart disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, Parkinson's disease, antidepressant use (time-dependent), antipsychotic use (time-dependent), use of anti-anxiety medications (time-dependent).

Discussion

Main findings and comparison with findings from other studies

We demonstrate that continued lithium use in older adults with bipolar disorder is associated with a reduced incidence of dementia diagnosis. This finding contrasts with the result for the negative control (use of anticonvulsants) for which no such effect was observed. Our cohort is broadly representative of publicly insured older patients with bipolar disorder in the USA and is one of the largest to date to examine the association between lithium use and dementia risk in bipolar disorder. These results are consistent with previous reports from Danish population-based registry data. The magnitude of the observed protective lithium effect in our study is smaller than that observed in the Danish registry data, Reference Kessing, Forman and Andersen10,Reference Kessing, Sondergard, Forman and Andersen11 particularly the >50% reduction in risk reported in individuals with bipolar disorder. Reference Kessing, Forman and Andersen10 Differences in effect size between studies may stem from the longer follow-up duration of the Danish study, differences in cohort composition and treatment patterns for bipolar disorder, or chance, as confidence intervals in both studies are wide. Although rates of psychotropic medication use are not directly comparable between our cohort and the Danish cohort, our observations underscore marked differences in psychopharmacological treatment patterns in the two studies. Whereas lithium was commonly used in Danish patients with bipolar disorder (50.4% over 10 years), it was more selectively used in the USA (18.3% over 4 years). The pattern was reversed for use of anticonvulsants with higher use rates in the USA (53.2% over 4 years) compared with Denmark (36.7% over 10 years). Antidepressants and antipsychotics were used in a majority of patients in both countries. The incidence of dementia was higher in the US cohort than in the Danish cohort (2.3% v. 1.0%), possibly because the US cohort was older and restricted to individuals on Medicaid.

As this is a non-randomised study from administrative claims data, our findings are open to alternative explanations. We employed multiple time-dependent exposure categories for lithium as well as a carefully chosen negative control exposure to examine the plausibility of the most pertinent potential sources of bias. First, the observed protective lithium effect could be attributed to channelling bias; i.e. the preferential selection of lithium over anticonvulsants for patients at lower risk for dementia. This possibility is supported by the fact that lithium-treated patients had lower baseline rates of cerebrovascular disease and diabetes than those treated with anticonvulsants, both of which have been associated with increased rates of dementia. Reference Crane, Walker and Larson26–Reference Skoog28 However, if channelling were the cause for the observed protective effect associated with lithium, then this protective effect would be expected to be present in all treatment durations relative to anticonvulsants rather than limited to continuous use as observed. Second, previous studies reported a protective lithium effect after only two prescriptions, which is suggestive of confounding by patient characteristics associated with lithium tolerability. By contrast, our finding of a lithium protective effect limited to continuous use over the previous year reduces concerns regarding such confounding. Third, a protective effect of maintenance medication treatment with lithium could reasonably be attributed to what has been described as the ‘healthy adherer effect’, in other words, confounding by healthy behaviours that correlate with medication adherence. Reference Shrank, Patrick and Brookhart29 Our finding of an absence of a beneficial effect for continued use of anticonvulsants reduces this concern.

Patients with bipolar disorder are at increased risk of developing dementia. Reference Kessing and Nilsson17–Reference Kessing, Olsen, Mortensen and Andersen19 Because several medication options exist for managing bipolar disorder, Reference Nemeroff22 it is important to evaluate whether they differ with respect to risk of dementia. Although consistent treatment with lithium appears to lower the risk of dementia, a similar protective association was not observed following treatment with mood stabilising anticonvulsants considered as a group. In practice, clinicians often make medical decisions not only on the basis of individual patient considerations such as treatment history, current presentation, patient preferences and known drug sensitivities, but also on the basis of comparative safety and effectiveness research. Reference Johnson, Sheard, Maraveyas, Noble, Prout and Watt30 In this context, the present findings add to the accumulating clinically relevant evidence that maintenance lithium treatment may delay or reduce the risk of dementia onset in older patients with bipolar disorder.

Limitations

Our study is also subject to limitations related to the use of automated claims data. First, dementia is underdiagnosed and undercoded in clinical practice, which raises concerns regarding the accuracy of our claims-based outcome definition. Reference Fillit, Geldmacher, Welter, Maslow and Fraser31 However, non-differential misclassification of the outcome from under- or delayed diagnosis or undercoding is expected to result in a conservative bias towards the null hypothesis. Reference Rothman, Greenland and Lash32 Similar claims-based definitions have been used in previous research and shown acceptable measurement characteristics. Reference Hebert, McBean, O'Connor, Frank, Good and Maciejewski24,Reference Gruber-Baldini, Stuart, Zuckerman, Hsu, Boockvar and Zimmerman25 In addition, the fact that established dementia risk factors, including age, alcohol use, cerebrovascular disease and diabetes, Reference van der Flier and Scheltens33 were associated with increased dementia in our sample provides empirical face validity to our claims-based dementia definition. Second, as with all claims-based studies, prescription fills only indicate medications dispensed, not those ingested. This could result in exposure misclassification and would, again, probably introduce a conservative bias towards the null hypothesis. Third, because of concerns regarding the accuracy of medical claims records in establishing dementia subtype, we did not differentiate between Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia. Fourth, with a maximum follow-up of less than 3 years, our study duration is relatively short compared with the lifetime duration of bipolar disorder and gradual onset of dementia. Similarly, lifetime exposure to lithium and anticonvulsants cannot be established from the data. Fifth, our study does not address the mechanism of the observed lithium-associated protective effects on dementia. Sixth, despite statistical methods to lessen concerns regarding confounding, we cannot completely rule out confounding in this non-randomised study.

Implications

The present findings support and strengthen the hypothesis that lithium exerts a protective effect on the development of dementia in patients with bipolar disorder. Because dementia has a devastating impact on the lives of patients, families and caregivers, and no curative or preventive treatments exist, our findings strengthen the rationale for extending clinical research on the potentially neuroprotective effects of lithium, including studies in patients who do not necessarily have bipolar disorder. The clinical trials with lithium in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia have been limited, and whether lithium exerts its protective effect through reduction in affective episodes, Reference Kessing and Nilsson17 inhibition of GSK3 Reference Klein and Melton5,Reference Phiel, Wilson, Lee and Klein6 or some other mechanism remains unknown. Systematic prevention or treatment trials to investigate the neuroprotective effects of lithium may be warranted.

Funding

This work was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (T.G.), AHRQ CERTs award U19 HS021112-02 for the Rutgers Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics (S.C.) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (D.P.D. and M.O.). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.