Standing on the corner of the intersection of Farm to Market (FM) 455 and FM 2450 roads, buffeted by the cold wind and stream of passing cars, Howard Clark spoke with warmth and curiosity as he handled the artifacts that likely passed through the hands of his ancestors. He considered his growing understanding and appreciation of blacksmithing through his own hobby work; Clark became interested in blacksmithing without knowing that his ancestor Thomas “Tom” Cook Sr., an African American freedman, was an important blacksmith along the Chisholm Trail in the late nineteenth century. Traversing a landscape of memories, Clark traced his family's history, which embodies the arc of rural and urban life in North Texas through the mid- to late nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, from enslavement through Reconstruction, Jim Crow and into the present. Reflecting on learning more about his family history, Clark remarked, “I didn't realize there was a whole other half of my family in [this] area. I'm driving by every other day or so [patrolling as a police officer]. Let alone a grave up there on that place. I had no idea any of this existed at all.” Folded into the archaeological team, Clark unearthed the iron craftwork and material remnants of his family and was a firsthand witness to the emerging image of the lives of his ancestors. A gregarious presence and avid storyteller, Clark would quip, “There we were. . .” to mark the beginning of a story and emphasize shared historical experiences, filled with both the joy and solemnity of life.

A car stopped along the side of the road, with its occupants stepping out and approaching the excavation site. Our archaeological team welcomed the visitors, offering them an informational handout. As we introduced the project and archaeological methods, we turned to Clark as he shared his family's story and his thoughts on the nonlocal specialists—whose team he joined too—who were meticulously digging on the street corner. By the end of the conversation, Clark and the visitors would usually discover that they had common acquaintances, and we would continue the work. Soon, another visitor would stop, and we would again share the story of Tom Cook and the communities of descendants and stakeholders who breathe life into the Bolivar Archaeological Project (BAP).

This article analyzes the research process of the BAP, illustrating how we can learn more together through archaeology as service and amplify an “undertold story” of African American blacksmiths on the Texas frontier through the material life of Tom Cook, an African American freedman living, working, and raising a family along the late nineteenth-century Chisholm Trail. Archaeologists working across governmental, academic, public, and private institutions have the capacity to impact descendant community members, stakeholders, and the broader public through practice designed to serve. The BAP demonstrates collaborative public archaeology as service by incorporating stakeholders into the project, thereby sharing authority and decision- making, developing relationships of trust and mutual respect, and co-producing knowledge. In this manner, the co-authors—including descendant community members Clark and Halee Clark Wright—bring people in to celebrate Black history by piquing curiosity and engaging community members with our research as it unfolds. The ultimate goal is to broaden the spectrum of empathy and support communities.

The BAP was conducted amid the broader urgency and growing awareness of long-standing historical inequities and the role of representation in archaeology (e.g., Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Franklin Reference Franklin1997). Considering this context, the BAP's research framework draws from the foundational Ransom Williams Farmstead Project. This was a Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT)–sponsored cultural resource management (CRM) project involving archaeology, archival research, descendant community collaboration, and oral history research (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Franklin and Myers2011, Reference Boyd, Norment, Franklin, Myers and Lee2014, Reference Boyd, Norment, Myers, Franklin, Lee, Bush and Shaffer2015; Juneteenth Jamboree 2010; Franklin Reference Franklin2012; Franklin and Lee Reference Franklin and Lee2020). Widely recognized for its community and public outreach, the project produced a two-volume oral history report highlighting recollections of descendant community members (Franklin Reference Franklin2012), a documentary film (Juneteenth Jamboree 2010), and an online educational exhibit (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Norment, Franklin, Myers and Lee2014) that includes lesson plans for fourth- and seventh-grade students (Schlenk and Liebick Reference Schlenk and Liebick2014). This exemplifies the substantial and rewarding impacts of incorporating descendants and stakeholders into the project.

The co-authors acknowledge the historical trauma of marginalized African American communities due to systemic and structural forms of racism and oppression. Building trust with descendant communities and engaging in the co-production of knowledge is a critical step toward a more socially just world. The BAP lies at the intersection of multiple historical, social, and disciplinary shifts convulsing the field and society at large, in addition to growing efforts to create collaborative and public archaeology (e.g., Ashmore et al. Reference Ashmore, Lippert and Mills2010; Bollwerk et al. Reference Bollwerk, Connolly and Mcdavid2015; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008; Dunnavant et al. Reference Dunnavant, Justinvil and Colwell2021; Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Skipper Reference Skipper2022; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2022). Through this, the collaboration centers on decolonizing and feminist critiques that destabilize historical systems of power by diffusing knowledge production across stakeholders and archaeological evidence (e.g., Atalay Reference Atalay2006; Franklin Reference Franklin2001; Haraway Reference Haraway1991; Liebmann Reference Liebmann and Stephen2018; Oland et al. Reference Oland, Hart and Frink2012). By practicing archaeology as service, the BAP and project members have become beholden to the descendants of Tom Cook and stakeholders as they are tied to their pasts.

To illustrate the collective voice that helped shape the BAP, this article was co-produced through the incorporation of conversations and interviews with Clark and Wright, descendants of nineteenth-century blacksmith Tom Cook. The authors represent the main collaborative groups for the BAP: Hanselka is the project manager for TxDOT, Menaker and Boyd are the co-principal investigators for Stantec; Franklin (Department of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin) is the community outreach coordinator and lead oral historian, and Clark and Wright are outreach liaisons with the local African American community. The BAP exemplifies the possibilities of practicing archaeology as service through building relationships of trust and mutual respect with stakeholders involved in the project, allowing for the co-production of knowledge. The article first outlines the process by which the project unfolded and focuses on the key themes emphasized by collaborators, including giving communities a voice and feeling heard by the archaeological team. Collaborators additionally reflected on their desire for the project to be responsive to the communities and to provide meaningful products for members. Moving forward, archaeological projects interested in archaeology as service can engage in community outreach at the earliest stages of project design and research, enacting inclusive practices that offer open-ended engagement and build relationships of trust and mutual respect, potentially leading to sharing authority and decision-making.

BOLIVAR ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT (BAP)

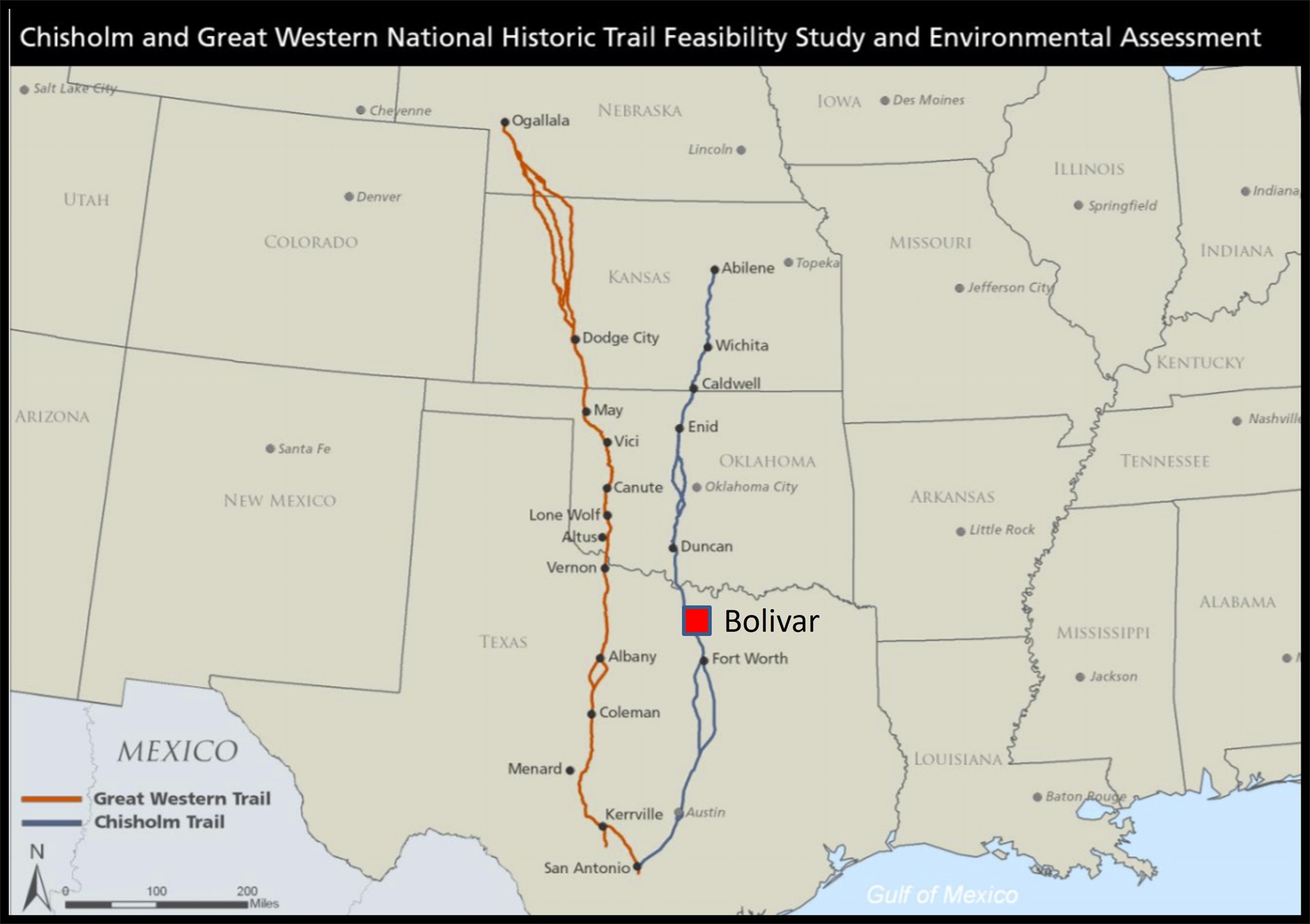

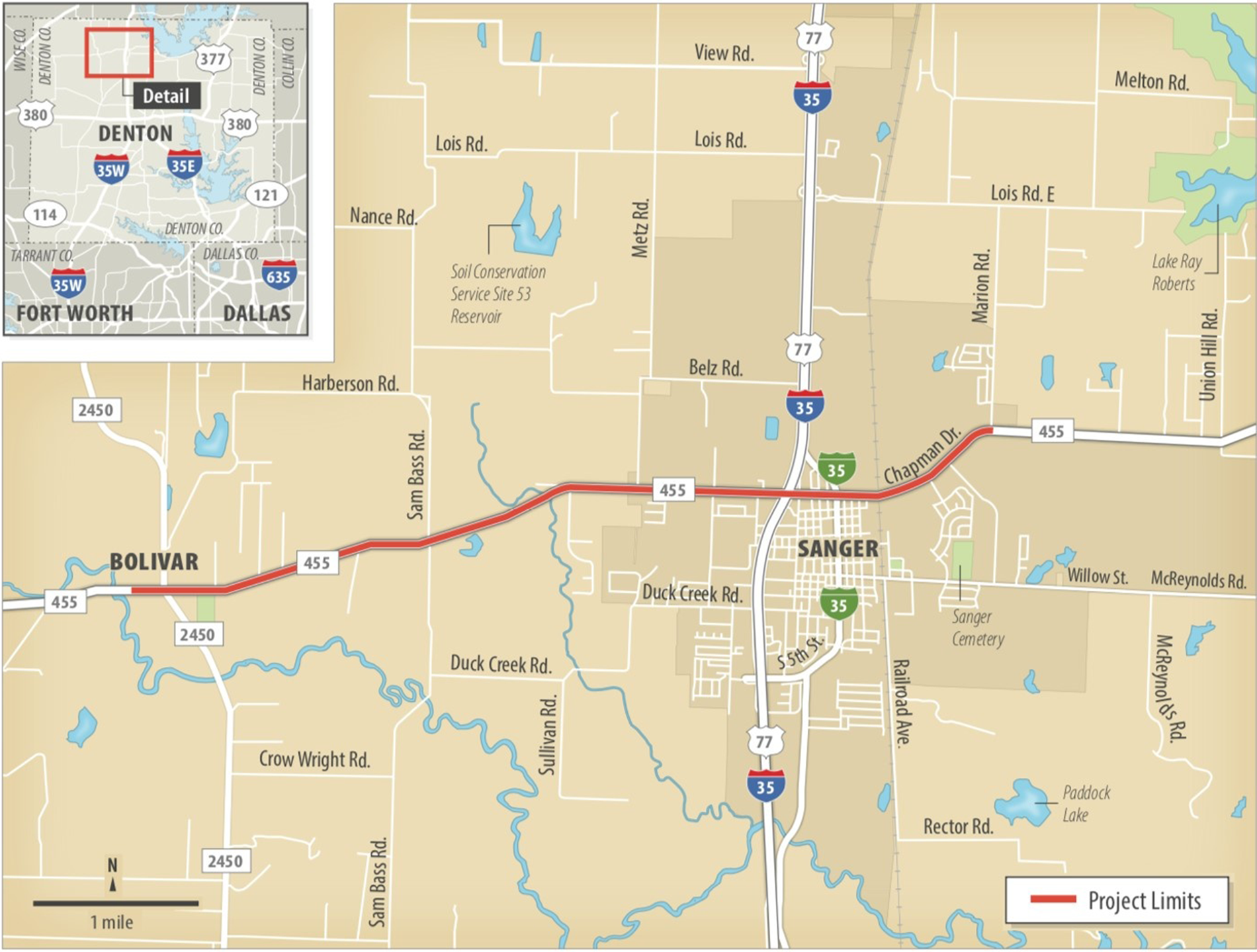

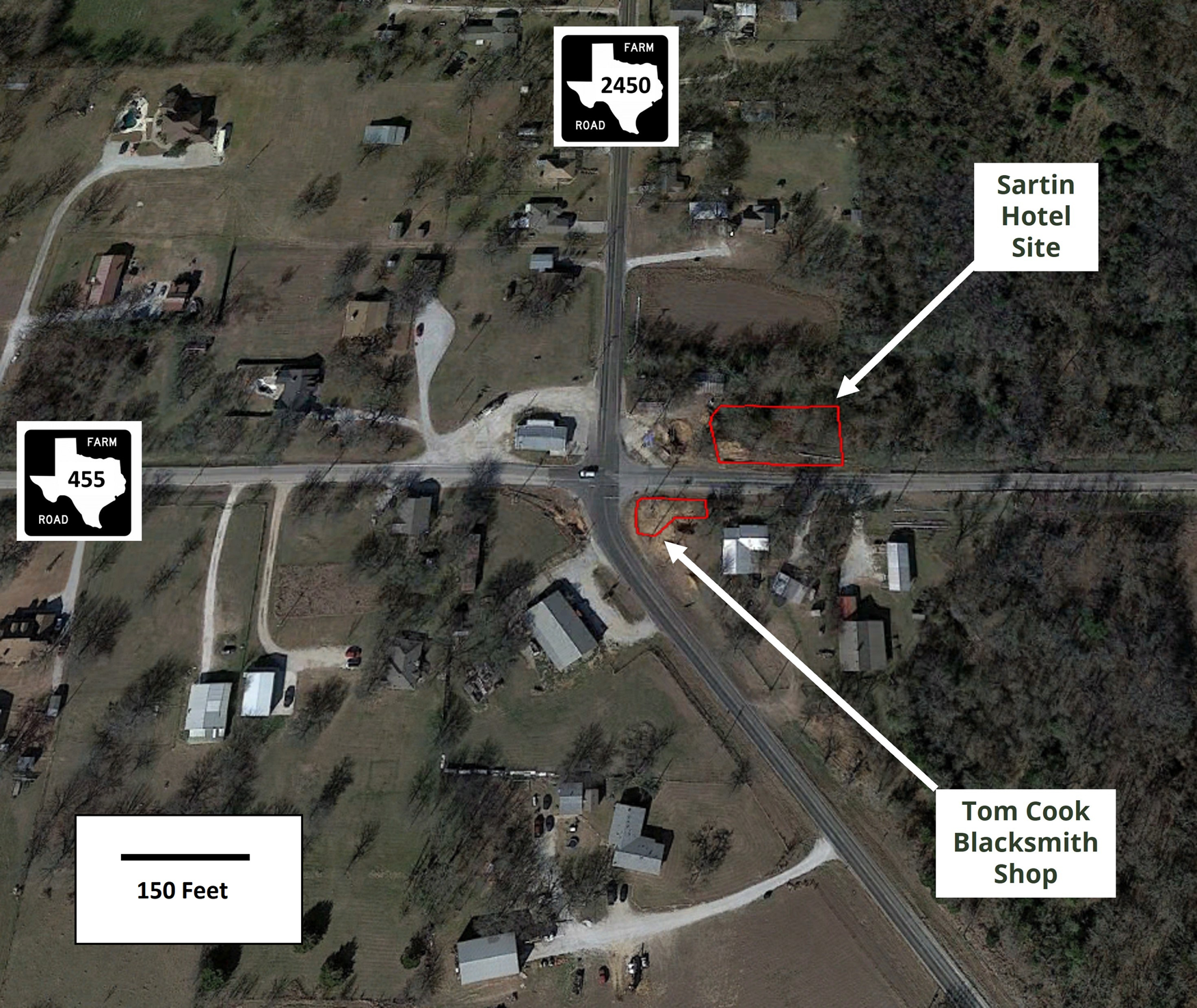

Proposed road expansion by TxDOT of FM 455 in northwestern Denton County, Texas, set in motion the initial archaeological surveys and testing between 2016 and 2019 of three nineteenth- to twentieth-century historic sites (Bonine and Parkin Reference Bonine and Parkin2019; Norment et al. Reference Norment, Parker and Wheaton2019). These sites were located in the Area of Potential Effects (APE) of road construction, with the project subject to state (Antiquities Code of Texas) and federal law and compliance of Section 106 under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). Following survey and initial testing, two nineteenth-century sites—the Tom Cook Blacksmith Shop (41DN617) and the Sartin Hotel (41DN593)—were found to be significant and warranted full-scale archaeological data recovery investigations prior to the road expansion project. The blacksmith shop consisted of a stone-walled dugout structure and artifact assemblages that offer insight into blacksmithing, commercial businesses, and ways of life on the Chisholm Trail and the Texas frontier. Although it was only in use as a cattle trail from 1867 to approximately 1886, Bolivar's location less than 4.8 km (3 miles) east of the Chisholm Trail made it an important stopping point for supplies and services (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

FIGURE 1. Map of Chisholm Trail (on the right) with Bolivar marked by red square (National Park Service 2010).

FIGURE 2. Map of broader TxDOT road project encompassing FM 455. (Credit: TxDOT Environmental Division.)

FIGURE 3. Aerial view of Tom Cook Blacksmith Shop and Sartin Hotel sites (Google Earth).

On June 10, 2020, TxDOT sponsored an online public stakeholder meeting and invited local groups, CRM firms, interested professionals, and the general public to participate. Although Menaker, Boyd, and Franklin watched the meeting, this was prior to their formal involvement in the project. Soon after the public meeting, Cox|McLain Environmental Consulting now Stantec (Stantec) was contracted by TxDOT to plan a multidisciplinary, collaborative public archaeology project for the sites. While the BAP is made possible and funded through a large state infrastructure project subject to public law and compliance, it is dedicated to public outreach and education, exemplifying the growth of a broader approach of public archaeology (e.g., Little Reference Little, Stig Sørensen and Carman2009; Tull Reference Tull2020). Hanselka notes that the BAP illustrates how collaborative archaeology projects under the auspices of a large state infrastructure institution—like TxDOT—are integral to the evolving breadth and opportunities toward complying with professional and regulatory standards, broadening project designs to serve multiple publics. In this way, the BAP has become a community-driven project expanding from traditional professional archaeology concerns through listening and incorporating the perspectives and interests of stakeholders into the project design. Before archaeological fieldwork, Stantec historians conducted in-depth archival research. Planning for the community outreach also began immediately, focusing on reaching out to the African American descendant community. This approach, emphasizing early outreach, recognizes the historical marginalization and inequalities of African Americans and their exclusion from participating in the production of history.

Following the lead of the Williams Farmstead project, the BAP was dynamic, allowing for considerable and meaningful opportunities for public outreach. Boyd and Franklin engaged the local community early in the planning stages, reaching out to Kim Cupit, the curator of collections with the Denton County Office of History and Culture, who shared her extensive historical research and knowledge of the African American community in Denton. This included research on the former Quakertown neighborhood in the nearby town of Denton, the residents of which were forced out in a racially motivated land grab in 1922 and replaced with a public park (Stallings Reference Stallings2015). With Cupit's research, the team possessed detailed information on the local descendant community, including the names of several of Tom Cook's descendants living in Denton. Franklin first contacted Clark, a retired law enforcement officer and the great-great-grandson of Tom Cook, who joined as an archaeological crew member, working on-site for the entire four months of fieldwork. Clark and Wright (a public schoolteacher and great-great-great-granddaughter of Tom Cook) were hired part time to serve as liaisons with the African American community in Denton. They became important team members and continue to work closely with Franklin on the ongoing outreach and oral history research (Figure 4). The oral history interviews with Tom Cook descendants complement the archival records that trace the family as its members moved from Bolivar to Quakertown and Denton. Their involvement provides a rich story of the family's post-emancipation journey, extending beyond the material culture from excavations and exemplifying the breadth and contributions of approaching archaeology as service.

FIGURE 4. Four generations of the Clark family—direct descendants of blacksmith Thomas “Tom” Cook Sr.—pose on the steps of the Quakertown House Museum in Denton: (clockwise from left) Halee Clark Wright, Betty Clark Kimble, Howard Clark, and Mylah Wills-Clark. (Photograph by Michael Amador. Courtesy of TxDOT [reproduced from Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Boyd, Hanselka, Clark and Wright2021].)

The archaeological team conducted extensive mechanical and hand excavations at the Tom Cook site (41DN617) from September 2020 to February 2021. This fieldwork incorporated the inclusive and collaborative approach through involving descendants, stakeholders, archaeology students, and publics. We also contacted colleagues about the opportunity for interested African American archaeologists to join the project. As a result, Anthony DeFreece, an undergraduate archaeology student at the University of North Texas at the time, joined the team as an archaeological crew member. North Texas Archaeological Society (NTAS) volunteers, including local youths who joined the NTAS to work on the BAP, assisted in screening artifacts. The BAP welcomed all visitors with a site tour (following appropriate COVID-19 safety protocols). These included unscheduled visits by curious local travelers, who observed our excavations, or others who “heard about the archaeologists” working there. Other site visits were arranged for interested parties and stakeholder groups, including a special visit by a large group of Tom Cook descendants (Figure 5). As recounted above, visitors were given handouts with historical information about the hotel and blacksmith shop, and they could access additional information via TxDOT's Beyond the Road web page, including Bolivar: The Once Wild West, which features summaries of archaeological and historical data from the project.

FIGURE 5. Four generations of Cook-family descendants visiting the Tom Cook Blacksmith Shop, with crew member Anthony DeFreece speaking about the project (reproduced from Franklin Reference Franklin2020).

Another significant component of our collaborative work was to incorporate an oral history program at the behest of descendants. This program served multiple, interrelated goals. First, it helped to build capacity among descendants to conduct research on their own past, including training Clark and Wright in oral history methodology. From the start, they both played an important role in the program by recommending interview questions and oral history themes, helping to identify interviewees, and conducting interviews. Second, it provided descendants with an opportunity to participate in the research directly and to co-produce knowledge regarding Black history and representation in Denton County. Consequently, the interviews were central to promoting “critical multivocality,” where “numerous perspectives and values are brought together to enlarge our shared understandings of the past” (Atalay et al. Reference Atalay, Clauss, McGuire, Welch, Atalay, Clauss, McGuire and Welch2014:11–12). Relatedly, the oral histories will help to contextualize and interpret the archaeological evidence from the Tom Cook site and will be integrated into a future museum exhibit that raises awareness of Black contributions to Denton's social, economic, and cultural life. Third, interviewees were asked for their perspective on Black representation in Denton County's public history narrative and on the Bolivar fieldwork. Their insights will hopefully assist local preservationists and public historians to address Black historical erasure moving forward. The oral history collection will be publicly accessible through the Oral History Program at the University of North Texas. In learning about Tom Cook, the BAP is working to broaden the archives of history for a more robust account of the past and present in North Texas.

WHO WAS THOMAS COOK?

The story of Tom Cook and his family has been at the margins of history for too long. The history of the Chisholm Trail has captivated the romantic imagination of the twentieth-century United States longer than the trail itself was in existence. While African Americans have often been omitted and underrepresented in the history of the cowboy past in the American West (e.g., Massey Reference Massey2000), an accurate historical account of the Chisholm Trail speaks of how Tom Cook, born enslaved, would eventually own land, practice a specialized craft, and become a leading figure in late nineteenth-century Bolivar, impacting generations. Clark and Wright did not know much about Tom Cook before the project began, and neither knew that he was a blacksmith. They were both aware of their ancestor, Jack Cook, who was Tom Cook's son and known for his work with horses. Through their expertise with horses, Tom Cook and his son Jack are emblematic of the cowboys of Texas. Clark notes that although American cowboys are commonly perceived as exclusively white men, Black cowboys were also integral to the past, wrangling animals on the landscape. Even though Tom Cook's life may be distant, Clark and Wright note how his story and life can resonate with people today. In this section, we offer accounts of Tom Cook across archival and historical documents, archaeological evidence, and the reflections of Clark and Wright.

There are few historical documents revealing information about the Bolivar blacksmith named Thomas Cook. Voter registration records indicate that Cook was enslaved when he was brought to Tarrant County, Texas, from South Carolina in 1857. The identity of his owner(s) remains unknown. Cook lived in Tarrant County at the time of emancipation and registered to vote there in 1867 (Ancestry.com 1867; Find a Grave Reference Grave2006). Tom Cook paid taxes in Tarrant County in 1870, but he had moved to Denton County and was paying taxes there by 1872 (Denton County 1870; Tarrant County 1874).

No historical data for Tom Cook or his family has been found in the 1870 US Census, and it is possible that he was missed by the census takers that year. However, the Ad Valorem tax records show that Cook paid taxes annually in Denton County from 1872 through 1897 (Denton County 1872–1897). The 1880 US Census population data show that Cook was a 40-year-old blacksmith in Bolivar, and that he lived with his wife Lethia (age 39) and eight children—Thomas Jr. (18), Samuel (14), Mary (13), Fanny (11), Walter (6), Kitty (5), Jack (3), and Toby (9 months; US Department of the InteriorCensus Office 1880a)Footnote 1. Cook also appears as a blacksmith in the manufacturer's schedule of the 1880 census (US Department of the Interior Census Office 1880b). The 1890 US Census data are missing (National Archives 2005), but a grave marker in the Knox Cemetery about 3.2 km (2 miles) northwest of Bolivar indicates that Thomas Cook died on January 5, 1898 (Find a Grave 2006)Footnote 2. A Texas State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1890–1891 lists all the commercial businesses in Bolivar, and it includes a listing for “Cook T, blacksmith” (State of Texas 1890:218).

Ad valorem tax and property deed records also show that Thomas Cook owned 0.4 ha (1 acre) of land in or near Bolivar in 1874, and in 1882, he purchased a 30.5 × 16.5 m (100 × 54 ft.) lot in Bolivar from James Barwis (or Barwise), who was an English blacksmith (Denton County 1882:V:36). This lot was situated at the main crossroads on the southern edge of town, directly across the street from the Sartin Hotel. It was an ideal location for a blacksmith shop, and it is likely that Cook purchased the lot and the blacksmith shop because he had been working there for many years. Although the relationship between Barwis and Tom Cook is unclear, the fact that both men were Freemasons is perhaps more than a coincidence (Dean and Scott Reference Dean, Scott, Dean, Grand Master, Scott and Grand Secretary1889:65; Find a Grave Reference Grave2008).

While these documents provide historical context, the historical record reveals little about the personality, achievements, and complexities of the man named Thomas Cook and is shaped by a lens that only recently claimed to recognize him as a full human with equal rights. Reading against the historical grain, we can glean some insight into the life of Tom Cook from a Denton County history from 1918, written approximately 20 years after his death. The document contains a brief history of Bolivar and a listing of prominent nineteenth-century Bolivar citizens that is compiled from various sources (Bates Reference Bates1918:87–89). This account notes, “Many of best citizens lived in this pioneer settlement who never failed to answer the roll call in time of danger, and we do not hesitate to call their roll now” This is followed by a listing of 136 white residents and 11 “colored” residents, including Tom Cook, who were considered the stalwart citizens of the community (Bates Reference Bates1918:87–89). This list of prominent Bolivar citizens was, of course, presented from a white historical perspective and would have been biased. Reading between the lines, however, this statement suggests that Tom Cook and 10 other Black men in Bolivar were effectively navigating life in a predominantly white frontier town.

Historical sources reveal a broader picture of Tom Cook beyond his craft of blacksmithing. He was also a Methodist minister, a Prince Hall Freemason, and a Worthy Patron of the Eastern Star, as well as a civil rights leader who influenced Fred Moore, a twentieth-century educator in Denton (Chambers Reference Chambers and Chambers1955, Reference Chambers and Chambers1965; Denton County News 1892, 1897; Grand Lodge of Texas 1889; Joppa Masonic Lodge Reference Lodge2022).Footnote 3 In 1892, the Rev. Thomas Cook was one of seven delegates selected to attend the “state conference of colored citizens to be held at Dallas on August 17” (Denton County News 1897). Apparently, Cook was also a barber, who would cut hair while patrons sat on his anvil (Waide Reference Waide1920–1930). It is likely that Tom Cook's blacksmithing skills were honed while he was enslaved. Prior to emancipation, blacksmithing and the people who held that knowledge and skill were among the highest-valued individuals within any plantation community (Berry Reference Berry2017; Burns Reference Burns, Abernethy, Mullen and Govenar1996). The historical record indicates that many other formerly enslaved blacksmiths from Texas and across the South went on to become community and church leaders, local city and county officials, or state legislators (Texas A&M 2002; Texas Historic Sites Atlas 1936, 1964, 1973, 1989, 2000).

Archaeological evidence in the form of blacksmithing artifacts and residues speak to the expertise of the smithy. After inspecting many of the forged iron artifacts and “drops” (cut or punched pieces that fall to the ground during forging), professional blacksmith Kelly Kring noted that Tom Cook was a “first-rate” blacksmith, who was adept at forge welding and other technical skills (Kelly Kring, personal communication 2021).Footnote 4 Burns (Reference Burns, Abernethy, Mullen and Govenar1996:180) notes that an African American blacksmith in East Texas said that forge welding was considered to be “the mark of a true blacksmith.” Artifact identification and analysis is ongoing, including continued collaboration with Kring to identify the personal forging marks of Tom Cook and possibly trace his shadow in hammerscale (the small particles that fly out as sparks during blacksmithing; Jouttijärvi Reference Jouttijärvi2009).

Through the years, Cook became an expert in a challenging craft and built a strong social web where he and his family thrived, despite living in a world that often viewed them as “less than.” Both Clark and Wright noted how his success provided a foundation for the family in the future. During conversations in preparation of this article, Wright emphasized how she considered Tom Cook “a badass,” and she noted the importance of Tom having purchased and owned his own land and blacksmithing business. Views encouraging owning land and a home were commonly stated by African American newspapers of central Texas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Lee Reference Lee, Boyd, Norment, Myers, Franklin, Lee, Bush and Shaffer2015). Despite many post-emancipation Blacks owning homes, land, and businesses, many contemporary and modern histories overlooked or ignored their success. Tom Cook, like countless others, worked hard to build a life and embodied the American dream. In the many public and private archaeology presentations describing the BAP, the Tom Cook story is always the most captivating part. The BAP embraces an approach to archaeology as service through engaging stakeholders as collaborators to co-author their histories, the history of the Tom Cook family, and Black history in Denton.

HAVING A VOICE

The co-production of knowledge is central to the shifting approaches and collaborative designs of archaeological projects that place representation as the cornerstone of collaborative engagement (e.g., Atalay et al. Reference Atalay, Clauss, McGuire, Welch, Atalay, Clauss, McGuire and Welch2014; Colwell Reference Colwell2016; Ferguson et al. Reference Ferguson, Koyiyumptewa and Hopkins2015; Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Franklin Reference Franklin2001; LaRoche and Blakey Reference LaRoche and Blakey1997; Lee and Scott Reference Lee and Scott2019; Oland et al. Reference Oland, Hart and Frink2012). In the BAP, descendants and local stakeholders were—and continue to be—woven into the fabric of the research design. This demands a good- faith effort grounded in an imperative to create space and transparency, allowing for listening, conversations, and collaborations with descendant communities and local stakeholders. Stakeholders and descendant communities are not singular but composed of multiple individuals and groups who may have varied reactions, interests, and agendas. In the case of the BAP, we had the privilege of working with direct descendants of Tom Cook, in addition to the broader African American descendant community and other local stakeholders. Stakeholders, in particular Tom Cook descendants, expressed shared and overlapping visions of archaeology as service implemented by the BAP, including representation, building relationships of trust, mutual respect and accountability, and the co-production of knowledge.

The BAP's flexible approach to public engagement gave community members and stakeholders different means of participating, ensuring that they felt involved regardless of time commitment and other factors, which allowed community engagement to blossom organically. Descendants of Tom Cook include Betty Kimble and Alma Clark, well-known community members and advocates. Both women were leaders in the Denton desegregation movement of the 1960s and had been previously interviewed to capture their recollections of Denton's Black history. Like these influential women, Clark and Wright are both authors of this story as well as part of the history. Clark and Wright note the archaeological team's respectful engagement with them and other stakeholders. Making time and acting with humility are at the core of these approaches. Wright, a working mother and schoolteacher, emphasized the archaeological team's consideration of her busy schedule and life, making time and accommodating accordingly. Ultimately, Clark and Wright expressed how they “never felt looked over.” The processes of forging relationships were crucial for the co-production of history through the BAP.

To create an inclusive account of history, it has long been a priority of the project to amplify and incorporate Clark's voice—from working together in the field to continuing conversations. Recently, Clark reflected on working on the archaeological dig at the site of the Tom Cook Blacksmith Shop—or “his Paw-Paw's,” as he would endearingly call it—and what the experience has meant to him. Menaker and Boyd asked Clark how they (the archaeologists) were able to build trust with him and the community during the BAP and to share his perspective of being involved in the fieldwork.

Clark recalls thinking dismissively when he first learned about the archaeological project. He shared that he received a phone call from Franklin and assumed that he “would be only a tool in the process” and that his involvement “would not amount to much.” Despite this, Clark joined the archaeological team on the first day of fieldwork and spent a week helping clear the overgrown vegetation at the site. He brought his own chainsaw and weed wacker, which ended up working better than the rental equipment. He acknowledged that he had “a guarded way” of interacting with the team at first. As the excavations began, connections and trust were forged, and Clark became increasingly encouraged by the archaeologists’ enthusiasm for and interest in the history and archaeological work. Clark noted how “open and free” the archaeologists were with information. He stated the following:

You weren't trying to make [the evidence] say anything or further any particular agenda. You just listened; whatever you uncovered, you tried to figure out what it was, catalogued it, placed it. We're trying to learn. You were kind of like how I try to be—open—and what is it going to tell me.

Through the process of co-laboring, Clark became invested in the project. In doing so, the project benefited from his presence in manifold ways. After years of sharp social observation and physical labor, Clark was well suited to screening the excavated fill and cultivated a feel for finding and identifying artifacts that had once passed through the hands of his ancestor. Clark, a retired police officer, brought practical awareness and thorough knowledge of the local people and landscape. When visitors stopped by, Clark would speak with the public, yielding important spaces to engage with Black history and communities in Texas.

Clark often speaks through humor when discussing difficult topics. He knows that this can be disarming, allowing for critical thinking to chip away at stereotypes and prejudices. He speaks through experience and discusses his active awareness of using humor to deliver uncomfortable truths. Through humor (“jacking with us”) and co-laboring, Clark came to embrace the project, “mainly because it was fun.” At the same time, Clark acknowledges navigating the fraught contemporary landscape, a world he inherited that viewed his ancestor as “living in a lower rung”:

I try not to stare it down and look for it, but yeah, it's noticeable. A lot of people don't think it is. My way of sometimes, like the humor. . . . You feed them with a little sugar coating that way you feed it to them in a way they can digest it and accept it and not know they are being fed.

Clark continued discussing his approach and the effects of using humor and joy in challenging people's perceptions:

A buddy of mine said, “Hey man, I think you change people. They haven't seen folks.” I said, “Well, they're conditioned to what's on TV and what they see on the media everywhere else and again what grandmammy and grandpappy told them when they were kids and coming up.” I'm doing everything I can to smash that. A lot of times when you attack somebody's family or their beliefs or whatever they've been brought up to think was right and you smash it with a hammer, yeah, they may have to accept the fact, but it usually just creates more resentment. But sometimes when you come at it with that odd angle and what you're saying is true, but it's wrapped in a little different package, they still have to think about it, but they can't get mad about it. There's no confrontation. And it's kind of easy. I do it because I enjoy the shock value, most of the time. With people, like you guys [archaeologists] I was working with, I would do that just to jack with you. It was fun and funny.

Clark consistently brought this thoughtful approach to communication with both visitors to the site and archaeologists. Co-laboring creates opportunities to foster mutual respect, solidarity, and shared empathy. It was widely viewed by the archaeology team that working with Clark and being involved with the project was a meaningful and rewarding experience.

The project found additional ways to engage other Tom Cook descendants and the broader local community. During the field phase, Franklin produced weekly “newsletters” that were emailed (and printed and handed out in some cases) to the African American descendant community. Additionally, the Cook and Clark families were invited to (and attended) a special personalized tour of the Bolivar excavations. On this tour, the research team highlighted the archaeological findings and displayed artifacts found at both sites for the four generations of Tom Cook descendants who were present at the site that day (Figure 5). In this way, history is not an abstract, distant concept but an embodied presence. In the short TxDOT documentary, Wright notes, “[Archaeology] brings out the intimate details of Black history so that it's more captivating, and I feel like if we were all more captivated by Black history, we'd know a little bit more” (Texas Department of Transportation 2022).

RAISING VOICES AND TELLING THE WHOLE STORY

The BAP strives to raise the visibility of the history of Tom Cook and the African American diaspora in North Texas through greater representation and the co-production of the history of Black life in the region. Betty Kimble and African American community members have long been aware of this local history, while many of their neighbors likely remain unaware. The erasure and marginalization of the history of Tom Cook and his family is exemplified by the location of the Texas state historical marker for the “Townsite of Bolivar,” which was installed in 1970. The marker was placed in a prominent location at the intersection of FM 455 and FM 2450, on top of where, 50 years later, archaeologists would identify the remains of his blacksmith shop and a dugout dwelling where his family once lived. No mention of Tom Cook is made on the historical sign. This section draws from extensive conversations with Clark and Wright to address the imperative of “telling the whole story,” as Clark refers to the process, and, through this, the politics and representation of Black history.

History is an active process that, by increasing representation, can produce more inclusive accounts of the past (e.g., Trouillot Reference Trouillot1995). The BAP deliberately moves away from archaeology's disciplinary roots in European colonialism and the continued marginalization of communities within the United States (e.g., Atalay Reference Atalay2006, Reference Atalay2012; Barkan Reference Barkan1999; Thomas Reference Thomas2004). In contrast, the BAP embraces a collaborative approach that yields both substantive research and meaningful opportunities for stakeholders. The project offers a richer understanding of the past and present by incorporating Clark's interpretations of archaeological evidence as well as his observations of the present landscape of North Texas while working alongside archaeologists during excavations.

In discussing Black history and identity, both Clark and Wright emphasized the often negative connotations associated with Blackness and Black history—if Black history is discussed at all. Through dehumanizing discourses that were central to systems of oppression, Black lives have been treated as static contradictions denied history and complexity (e.g., Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Blackmon Reference Blackmon2008; Gilroy Reference Gilroy1993; hooks 1992; Lee Reference Lee, Boyd, Norment, Myers, Franklin, Lee, Bush and Shaffer2015). Clark underscored how Black history is not reducible to slavery: “Slavery's not where we started. That's something we came through, we lived through.” Clark and Wright emphasized the value of “telling the whole story” and striving for a richer portrait of human life even if it may be uncomfortable. In these conversations, Clark and Wright further affirmed how learning this history has empowered them personally, and they noted how social and historical awareness through education are central to a thriving society.

Interviewing Clark, he reflected on learning about his family and Tom Cook, telling the whole story, and how the BAP served him:

This helped a whole lot. It was, like I said, it was emotional to me. Most Black folks, I say most, that may not be accurate, but most Black folks, they know a little bit, a short history, but once you get way back, it starts to go, well, because you don't know who they were, who they worked with, whose name they took when they got here. You know really it only goes back so far. Now I know not every Black person is a descendant of slaves either, and some of those can probably trace back to wherever, but most of us don't have that depth of history. That's just the way it is. That's the way it was intended to be, I think. To separate, cut you off from all that you know. It's easier to control you when you don't know anything about where you come from and who is on your side.

Clark further noted the importance of being uncomfortable and that part of telling the whole story involves teaching history: “If it happened, teach it. Even if it is uncomfortable!” At the same time, Clark recognizes people as multifaceted and living history:

I put a post one time on Facebook that said a lot of people are comfortable with history or stories as long as it makes them look good and like they are the heroes. They get uncomfortable when it starts to show either other folks in that role or the truth about where they come from. They don't like that part of it. They want to wipe it, but it's history. Everybody I know has done something they wish they hadn't. And they wish they could go back. But it doesn't change, doesn't make me think any different of you. You're here now.

Speaking of the Cook family history and narratives of Black history, Clark stated,

[Our family history] doesn't fit that narrative of we were just sitting around waiting on everyone to give us something and being lazy. I don't know where that came from. But if you're not careful, that's what people will hammer into you, and you'll start to believe it, whether you realize it or not. Anything like this, what we're talking about now, is enlightening. It's just more fuel for disproving some of the myths. It's not directed at anybody. There's no hate involved in this. It's just the truth.

I don't look at you [with a grin, Clark gestures at Menaker sitting across] and go, “You are my oppressor because I see you. You must have been.” That's not what it is. We have a story that's just as good as yours. Why are we so afraid of telling the whole truth? And my being able to participate, and actually there being almost a physical connection with the blacksmithing thing, that just made it all the sweeter. I'm doing something that I wish my great-great-grandfather could see. . . . This is about as close as I can get to [Tom Cook] on this side.

Clark and Wright emphasized the imperative of studying and teaching history. Black history does not involve erasing other histories but seeks to widen the scope of history. In this way, archaeology is uniquely poised to spur curiosity and cultivate empathy. The BAP is dedicated to continuing to share these histories with a range of audiences and amplifying the history of Tom Cook as well as the process of this project.

Beyond the site of the blacksmith shop, the BAP has led to several activities for Tom Cook descendants, including Clark and his family visiting the grave site of Tom Cook. This resulted in the publication of the article “Finding Tom Cook” in the Texas Heritage Magazine, a broadly read, public regional magazine (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Boyd, Hanselka, Clark and Wright2021). Future outreach efforts include, but are not limited to, roadside historical markers, educational curricula, publications, museum exhibits, and community outreach events. Designs for several interpretive road sign markers will tell the story of Tom Cook, presencing Black history and Tom Cook's role in blacksmithing on the Texas frontier and the Chisholm Trail. TxDOT has also produced a short documentary available to the public through the project web page. The project has been featured in the magazine American Archaeology, in an article titled the “Purpose of Archaeology,” which highlights the project as a model for collaboration moving forward (Lunday Reference Lunday2021). Project members also participated in the recent Texas Archaeology Fair in Denton, preparing several posters on the project as well as incorporating stakeholders and descendants into the event. This included a blacksmith exhibit by Kring and Clark, demonstrating how Tom Cook would have made some of the artifacts (see Givan Reference Givan2023). Continuing such community outreach, the BAP held another blacksmithing exhibit and artifact display incorporated in the Juneteenth parade in Denton.

Teaching histories that offer inclusive accounts of Black life, as Clark and Wright note, serve as counter-narratives to a history that negatively depicts and contributes to the erasures and marginalization of Black lives in both the past and present. Moreover, Clark and Wright emphasized that historical awareness is integral not only to their own growing understanding of their place in the world but also to everyone. This requires extending beyond traditional and institutional forms of historical knowledge production by reaching out to community members and descendant communities. Through the involvement of the Cook family, Betty Kimble, Clark, and Wright, the results and ongoing directions of the BAP affirm collaborative archaeologies dedicated to professional standards and compliance requirements under federal and state laws. Through greater representation of descendant communities and stakeholders in dialogue with archaeological research, a more robust history can be written that allows for people in the present to see their past, empowering their future.

CONCLUSION

The BAP exemplifies the possibilities of archaeology as service through an inclusive and collaborative project design and practice. Prior to conducting excavations, the project reached out to local institutional contacts to identify descendant and stakeholder community members. Although this initial contact was met with skepticism, the project incorporated descendants and stakeholders by offering people multiple ways to be involved and represented. This includes Clark co-laboring through the excavation of his ancestors’ blacksmith shop. The BAP shares research results with and continues to learn from different local and institutional sources, including by sending weekly newsletters and offering field and lab visits. In addition, descendant and stakeholder labor was and continues to be compensated. Through the collaborative process and creating spaces for accountability and shared decision- making, project members and stakeholders were able to develop relations of mutual trust and respect as we co-produce knowledge about the history of the site, Tom Cook, and Black history in Denton. The BAP is among a growing number of collaborative and public archaeology projects inviting archaeologists working across institutions to integrate community outreach and engagement into the life of a project. From Ransom Williams to the BAP, as a leading institution in the field of Texas CRM archaeology, TxDOT demonstrates how large public infrastructure institutions are committed to supporting and investing in collaborative, public archaeology projects.

Archaeology as service is a process made and remade through practice. A collaborative archaeology does not view archaeologists as the only arbiter of truth and history but rather decenters the position of power to give space and voice to descendants and stakeholders in writing their own histories. Attending to stakeholders’ perspectives in addition to technical, archaeological knowledge was critical to building trust with Clark, Wright, and the broader descendant and stakeholder community. While there is much more work to do, the collaborative, public, and inclusive approach of the BAP affirms the impacts and stakes of archaeology.

At the intersections of this history between Clark and Tom Cook is Quakertown. It was through historical research at Quakertown that led the Bolivar archaeology team to the Cook descendants. Quakertown was a thriving Black urban community in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and its erasure exemplifies the legacies and transformation of policies and practices that marginalized Black communities beyond the life of Tom Cook (Stallings Reference Stallings2015). While writing this paper, Clark joined Menaker and Boyd for a videotaped interview in the garden of the Quakertown House African American Museum in Downtown Denton. It is one of the few surviving Quakertown houses and was moved to its current location. To end, we draw from Clark's interview in Quakertown, as he spoke of the importance of archaeology, handling the artifacts, and what this project means to him personally and Black history more broadly:

This helped me a whole lot. It did give a me a sense of pride. I don't want to be a prideful person, that's not what I'm trying to say. Now I can speak a little further about, well, this is what we did. I knew we had people that were blacksmiths, not in my family necessarily, but I knew they were there. I knew there were business owners. I knew there were just about anything anybody else had maybe just to a smaller degree in a rural area. But this was kind of like, now I can speak of it kind of from a personal experience in my own family. It's just shedding more light on the story every day. Every time something like this unfolds. It makes that other story people want to tell a little bit harder to instill. . . . There's a whole truth that's out there.

Acknowledgments

The BAP is made possible through a range of institutions and people, with the Texas Department of Transportation supporting the investigation, collaborative approach, and community outreach for the project. We are grateful to all descendant community members and local stakeholders, Cook and Clark descendant family members, African American descendant community members, blacksmith Kelly Kring, the Curtsinger family, and many others. Thank you to Kim Cupit and the Denton County Office of History and Culture, and Gary Hayden with the Denton County Historical Commission. The project appreciates the contributions and support of Texas archaeological societies, in particular the North Texas Archaeological Society. Stantec Consulting Services, Inc. supported this publication and facilitates the investigation and collaborative approach of the project. The BAP is permitted under Texas Antiquities Permit No. 9649 by the Texas Historical Commission.

Funding Statement

The manuscript was completed by the authors on their own time and with funding support from Stantec Consulting Services Inc. The project is funded by TxDOT.

Data Availability Statement

This publication is based on ongoing research. Some of the information is already publicly available and cited accordingly in the document. The ongoing research and analyses will be made available to the public and interested parties per the permission of associated stakeholders.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.