1. Introduction

In 1977, Bruce Metzger reported that ‘[e]xcept for the Sinaitic and Curetonian manuscripts no other copy of the Gospels in the Old Syriac version has been identified with certainty’.Footnote 1 The situation changed in 2016 when Sebastian Brock introduced the extant part of a third manuscript, based on multi-spectral images produced by the Sinai Palimpsests Project.Footnote 2 Six folios from a Gospel manuscript are present as undertext in Sin. syr. M37N, and another seventeen and a half folios of the same manuscript were identified in Sin. syr. M39N. According to Brock, the Gospel manuscript is datable to the sixth century.Footnote 3

In the course of my recent study of the Syriac undertexts present in the manuscript Vat. iber. 4, it has been possible to identify the Syriac Gospel text on ff. 1 and 5 as containing Matt 11.30–12.26 in the Old Syriac version.Footnote 4

Vat. iber. 4 was likely acquired by the Vatican library in the mid-20th century.Footnote 5 Although – thanks to a brief note by a Georgian scholar M. Tarchnišvili – scholars were already aware of it in 1953, since then the manuscript has been considered lost.Footnote 6 In 2010 the manuscript was re-discovered and in 2020 it was digitised, and the resulting natural light and UV images were added to the Digital Vatican Library.Footnote 7

The Vatican manuscript is, in fact, only a membrum disjectum that originally belonged to a Georgian manuscript kept at the monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, under shelf mark Sin. geo. 49 and containing the Iadgari (collection of liturgical hymnography).Footnote 8 This Georgian manuscript is a palimpsest throughout and was produced from multiple parts of originally independent manuscripts in various languages. In its present form, codex Sin. geo. 49 is defective and lacks the first twenty quires, as well as some leaves at the end, including a colophon. Despite the loss of the colophon, analysis of the manuscript's handwriting led specialists to propose that it was copied by a well-known Georgian scribe, Iovane Zosime, who was active during the second half of the tenth century, first at the monastery of St. Sabas in Palestine, and later at the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai.Footnote 9

The remaining part of the manuscript kept at the monastery does not seem to contain other leaves that belonged to the same Gospel manuscript as the fragment preserved in Vat. iber. 4.Footnote 10 The identification of further membra disjecta may bring to light additional leaves of the same Gospel manuscript.Footnote 11

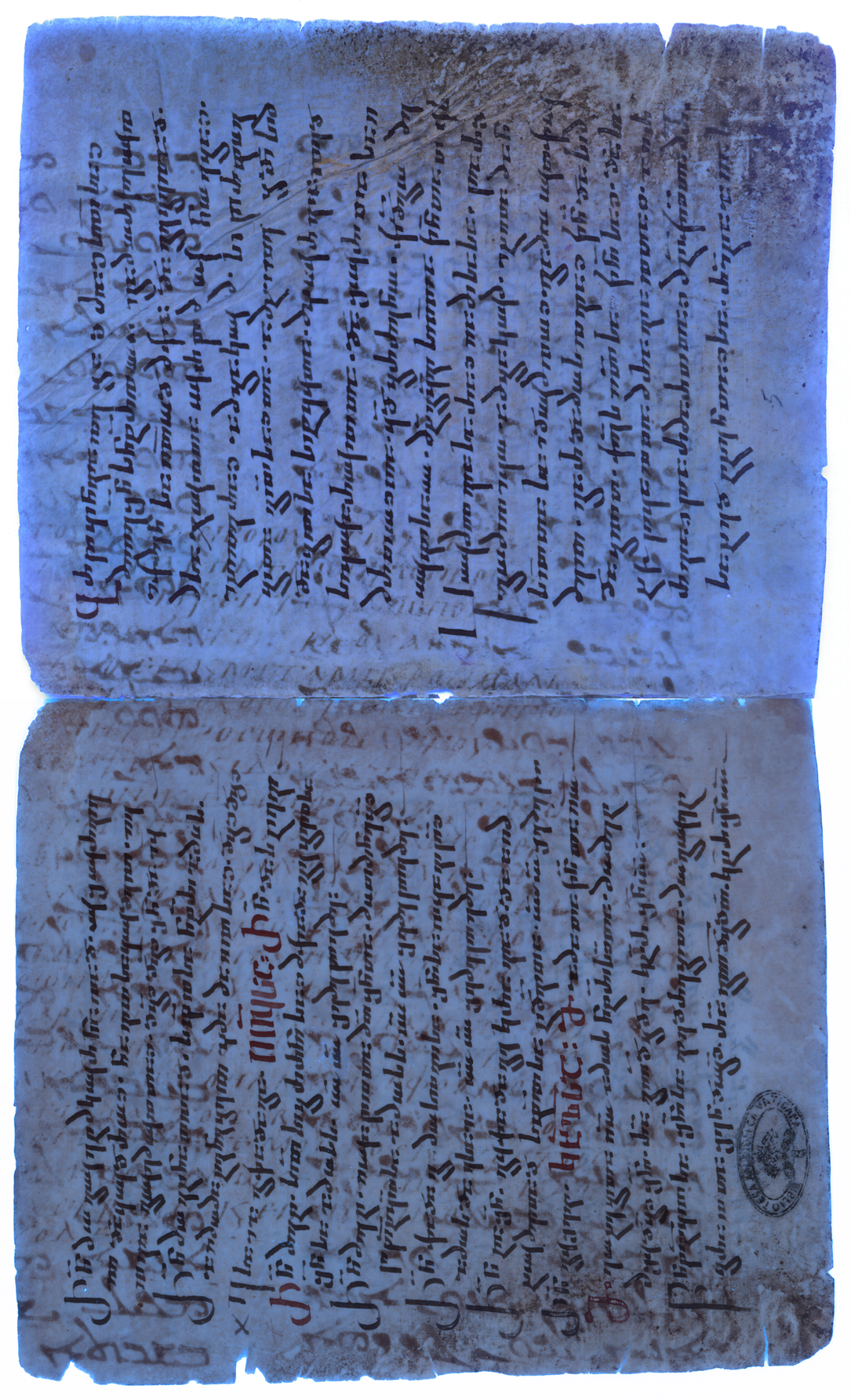

Ff. 1 and 5 of Vat. iber. 4 constitute a bifolium. Within the original Syriac Gospel manuscript, this bifolium was a single leaf, with Gospel text arranged in two columns with 28–30 lines. The recto side of the leaf is today ff. 5r+1v, whereas the verso side is 5v+1r. The presence of two sewing stations on the right-hand side of f. 5r and f. 1v enables us to posit that within the original Gospel manuscript this leaf formed the left-hand side of the bifolium.

Thus, an original bifolium from a Gospel manuscript was cut in two, trimmed, and folded for reuse as a bifolium in the production of the Georgian manuscript. As a result of the trimming, about half of one of the columns was cut off, as well as a side and a lower margin.

In its present form, the size of the trimmed Syriac leaf is 27 × 15.7 cm (the page size of Sin. geo. 49 is 15.7 × 13.5 cm). In its original form – before it was trimmed – a folio must have measured ca. 30 × 23 cm. A Gospel book Vat. sir. 12, dated to 548 CE, is roughly the same size, 30.4 × 23.6 cm. The Curetonianus (British Library, Add. 14451) likewise has similar dimensions, 30 × 24 cm. On the other hand, both the Sinaiticus and the fragmentary manuscript of the Old Syriac Gospels studied by Brock are of somewhat smaller size, ca. 22 × 16 and 22 × 17 cm respectively (the folios of both manuscripts were trimmed but only slightly). Hence, the original Gospel manuscript to which the Vatican fragment once belonged, was of significantly larger size than both the Sinaiticus and the fragmentary Gospel manuscript.Footnote 12 Consequently, there remains no doubt that the original Gospel manuscript of the Vatican fragment is different from that whose fragments are today preserved in Sin. syr. M37N + M39N.

Given that the text of the Vatican folio represents roughly 0.6% of the complete text of the Four Gospels, the original Gospel manuscript must have occupied some 160 folios, or sixteen quires.Footnote 13 For the sake of comparison, one might mention that the Sinaiticus in its original form consisted of some 164 folios; Curetonianus, 177 folios; and the fragmentary manuscript of the Old Syriac Gospels, 150 folios.Footnote 14

As far as the dating of the Gospel book is concerned, there can be no doubt that it was produced no later than the sixth century. Despite a limited number of dated manuscripts from this period, comparison with dated Syriac manuscripts allows us to narrow down a possible time frame to the first half of the sixth century.Footnote 15

The Syriac Gospel manuscript, in its turn – or at least the folio under consideration – was reused for the Apophthegmata patrum in Greek.Footnote 16

Collation of the Gospel text based on the UV images produced by the Vatican library, enables us to establish that the extant text is identical to the Curetonianus (British Library, Add. 14451). Although in a number of instances the Curetonianus and the Sinaiticus agree against the Peshitta (Matt 12.5, 12.6, 12.7a, 12.7b, 12.8, 12.10a, 12.11b, 12.12, 12.13, 12.19a, 12.24b), there is significant evidence to demonstrate the absolute agreement of the Vatican fragment with the Curetonianus as against the Sinaiticus (Matt 12.1b, 12.2, 12.3, 12.4, 12.9, 12.10b, 12.11a, 12.16, 12.17, 12.19b, 12.21, 12.22, 12.23, 12.24a, 12.25).

It goes without saying that a discovery of a new witness to the Old Syriac version, and specifically its remarkable agreement with the Curetonianus, deserves to be studied in the context of the transmission history of the Gospel text in Syriac.Footnote 17 It is particularly worthy of consideration, if this new witness can contribute to the evaluation of the text attested by the Curetonianus as being more widespread and authoritative, as opposed to the text of the Sinaiticus. Before any definitive conclusions are drawn, it is, however, greatly hoped that further leaves of this Syriac Gospel book will be detected among the yet-to-be-found membra disjecta of codex Sin. geo. 49.

Collation:Footnote 18

Diplomatic editionFootnote 19

Figures 1–2. Vat. iber. 4, ff. 5r + 1v (= recto)

© Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Reproduced by permission of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved.

Figures 3–4. Vat. iber. 4, ff. 5v + 1r (= verso)

© Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Reproduced by permission of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to Dr David G. K. Taylor who read the earlier draft of the paper and made valuable suggestions that helped to improve my reading of the palimpsest.

Funding statement

The Institute for Medieval Research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences generously supported publication of this article in open access.

Competing interests

The author declares none.