Background

Paediatric to adult health care transition is a major event for patients with chronic health conditions requiring lifelong care. Preparation processes have been described but without outcome evaluation details. Reference Dahdah, Kung and Friedman1–Reference McManus, White, Pirtle, Hancock, Ablan and Corona-Parra5 Children with Kawasaki disease resulting in coronary artery complications, specifically coronary artery aneurysms, require health care transition for lifelong follow-up with an adult care specialist to avoid cardiovascular morbidity. Occasional feedback from post-health care transition young adults with Kawasaki disease and coronary artery aneurysms (for the purpose of this report either “complex Kawasaki disease” or “Kawasaki disease with coronary artery aneurysms”) suggested that the transition was very difficult. Given the gap in the literature Reference Moons, Skogby, Bratt, Zühlke, Marelli and Goossens6 and our feedback, programme redevelopment began with a closer examination of the patient experience.

In North America, the estimated annual Kawasaki disease incidence is ≈25 cases/100,000 children < 5 years of age (males to females ≈ 1.5:1). Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4 Those with large coronary artery aneurysms (Z-score ≥ 10) risk outcomes which can lead to myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, or sudden death. Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4,Reference Tsuda, Hamaoka and Suzuki7 An International Kawasaki disease Registry review of patients with coronary artery aneurysms (n = 1,641) identified complications such as luminal narrowing and/or coronary artery thrombosis among those with large or giant aneurysms. Reference McCrindle, Manlhiot and Newburger8 Long-term follow-up is, therefore, recommended. Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4,Reference Dimitriades, Brown and Gedalia9,Reference Manlhiot, Niedra and McCrindle10 Similar to children with chronic CHD, the majority of those with complex Kawasaki disease are expected to survive into adulthood. Reportedly, >50% of those with CHD are lost to follow-up post-health care transition, Reference Heery, Sheehan, While and Coyne11,Reference Warnes, Williams and Bashore12 but post-transition follow-up for those with complex Kawasaki disease remains underexplored. Reference Denby, Clark and Markham13 Forty per cent of respondents from the Japanese Society of Kawasaki disease identified health care transition losses to follow-up for patients with complex Kawasaki disease. Reference Kamiyama, Ayusawa, Ogawa, Saji and Hamaoka14 The 2017 American Heart Association guidelines stressed the importance of assessing psychosocial needs in addressing gaps in Kawasaki disease transition. Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4

Kawasaki disease cardiovascular complications and long-term management

The Kawasaki disease mortality rate is reportedly < 1%, Reference Chang15–Reference Singh, Vignesh and Burgner17 but the risk for morbidity is significant for complex Kawasaki disease patients (coronary artery aneurysms, Z-score>2.5) Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4 such as aneurysmal arterial wall calcification in giant aneurysms, and a ∼ 64% risk for a major cardiac event within 30 years of their Kawasaki disease diagnosis. Reference Tsuda, Hamaoka and Suzuki7 A 50% risk is associated with thrombotic coronary occlusion, progressive stenoses revascularisation, acute coronary syndrome, myocardial ischaemia, and later, serious arrythmias and heart failure. Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4,Reference Suda, Iemura and Nishiono18

Health care transition and transition from adolescence to adulthood

Successful health care transition has been defined as achieving continuity of optimal health care across the lifespan through learning self-management skills to undertaking independent responsibility of health care and other personal responsibilities. Reference Kovacs and Webb19 Preparing for health care transition is a process that should assist adolescents in taking independent control of their lives, including their health management. Reference Knauth, Verstappen, Reiss and Webb20,Reference Knauth, Bosco, Tong, Fernandes and Saidi21 The transition from adolescence to adulthood is a critical period involving physical and psychosocial changes and decision-making obligations Reference Knauth, Verstappen, Reiss and Webb20–Reference Wood, Crapnell, Lau, Halfon, Forrest, Lerner and Faustman24 for independently managing ongoing health care in a new clinical setting. Recently, the World Health Organization expanded the age range for adolescents from 10–19 years to 10–24 years, owing to rapid biological growth, changes in social roles, new demands and responsibilities, and ongoing brain development, all of which compound their chronic condition. Reference Brenhouse and Andersen25–Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton28 To face the physical changes, societal demands and expectations, adolescents are required to master specific developmental tasks, in establishing their identity. Reference Luyckx, Goossens, Van Damme and Moons29,Reference Miatton and Sarrechia30 Lapses in care during the transition period are unfortunately common and associated with poor health outcomes Reference Kovacs and McCrindle2 that may result from insufficient disease knowledge, lack of essential skills for self-care, Reference Varty and Popejoy31 or other psychosocial issues.

Readiness for change has long been identified as the essential mediator and motivator of behavioural change. Reference Boswell, Sauer-Zavala, Gallagher, Delgado and Barlow32,Reference Stein, Minugh and Longabaugh33 Readiness is a central phenomenon and a key step in health care transition assessment and preparation Reference Cooley and Sagerman34–Reference Straus36 and considers the adolescent’s age, capacity, capability (self-efficacy) for self-care, and their attitude about leaving paediatric care. Reference van, van der, Jedeloo, Moll and Hilberink37 Transition programme recommendations have been laid out with age-appropriate core elements, Reference Dahdah, Kung and Friedman1,Reference McManus, White, Pirtle, Hancock, Ablan and Corona-Parra5 but follow-up outcome evaluation is not included within the health care transition elements.

The importance of an evidence-based and theoretically informed research (replete with the myriad behavioural constructs) is established as a cornerstone of clinical care. Reference Schwartz, Tuchman, Hobbie and Ginsberg38 A theory-based research approach is recommended for the design, intervention, and the analysis, enhancing both a programme’s effectiveness and generalisability. Reference Cowdell and Dyson39,Reference Glanz and Bishop40 The Theoretical Domains Framework for behaviour and behavioural change specifically related to self-care was chosen for this study. Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam41 The Theoretical Domains Framework includes a constellation of factors with three key components at interplay in self-care change: capability, opportunity, and behavioural motivation (COM-B). Reference Michie, Atkins and West42 Due to the effectiveness of the Theoretical Domains Framework in other screening intervention studies and its suitability for a qualitative approach, the Theoretical Domains Framework was used to support this exploration, the research question of which was what are the post-health care transition, complex Kawasaki disease participants’ experiences (concerns, expectations, preferences, disease knowledge, perspectives, and recommendations) regarding transition readiness, motivation, and self-management?

Methods

Methodological approach

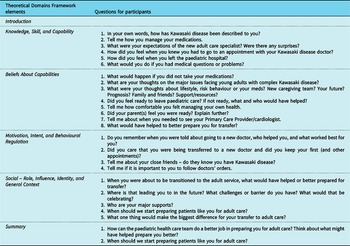

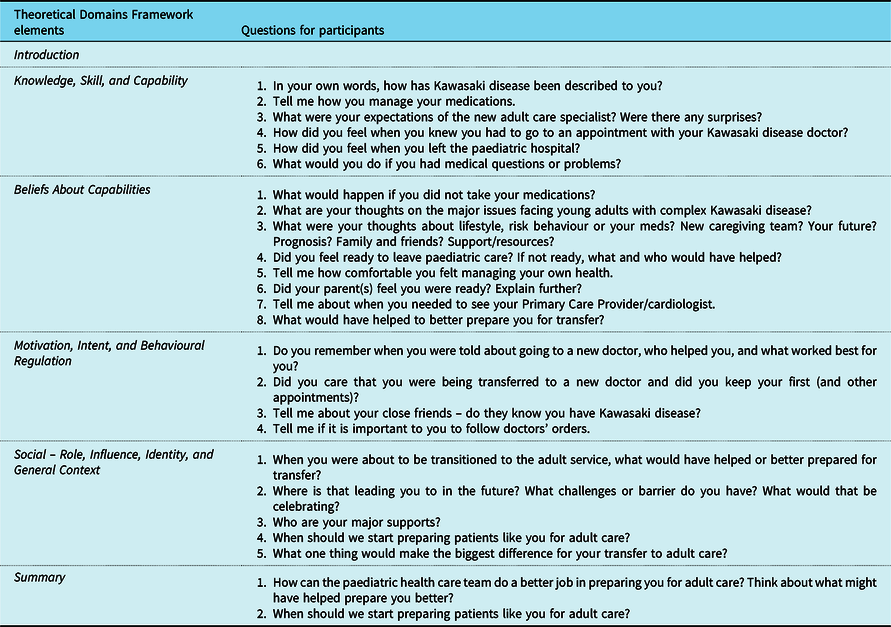

A qualitative description research method Reference Sandelowski43 was used to understand and describe how those with complex Kawasaki disease experienced their transition to adult care. This method is used when little is known about the phenomenon of interest and when a baseline understanding of the issue is warranted. The interview questions followed a predeveloped guide informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (Table 1). Directed content analysis Reference Hsieh and Shannon44 was employed to align the categories of expressions and experiences with the Theoretical Domains Framework. Anticipated was a deeper understanding of how young adults with complex Kawasaki disease experienced transition. Virtual interviews via MS Teams® with consenting young adults with complex Kawasaki disease were conducted.

Table 1. Interview guide questions were generated using the Theoretical Domains Framework.

Inclusion criteria and sample

Included were post-health care transition individuals with complex Kawasaki disease (age 18–30 completed years), at least 1-year post-diagnosis, and able to speak English. Complex Kawasaki disease was defined as those with coronary artery dilatation or aneurysm(s) (z-score ≥ 2.5 per the American Heart Association 2017 Kawasaki Disease Guidelines), Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4 and taking antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant medications at the time of transition. Non-English-speaking individuals, those with known developmental delay, or those who may have a diagnosed mental health concern were excluded. Our sample size was purposeful, one of “convenience,” and included those interested in participating over the months of November and December 2022 time frame.

Sample size determination was based on the current literature and pragmatic considerations; a sample of ∼ 12 participants is likely sufficient to reach data saturation when the sample is alike. Reference Guest, Namey and Chen45–Reference Vasileiou, Barnett, Thorpe and Young47 Our aim was to interview up to 15 participants or until data saturation was obtained.

Recruitment

Potential participants were obtained through informal and post-transition connections with the Nurse Practitioner at the paediatric centre, from adult care partner(s), or web-based Kawasaki disease advertisements (websites: Kawasaki Disease Canada Parent Awareness Group [https://www.facebook.com/KDCanadaPA/], Kawasaki disease Support [Facebook group], and Children with Aneurysms [https://www.facebook.com/groups/KDaneurysms/]), the latter being a closed parental group for parents of children with complex Kawasaki disease. The online administrators posted study details and investigator contact details. An information letter was available in the (adult) cardiology clinic. The study Research Assistant communicated with interested volunteers via telephone to provide the study’s purpose and details and determine eligibility. Eligible participants were provided with an electronic consent form via REDCap®. Interviews were scheduled after full consent.

Data collection

All interviews were scheduled for 60 minutes, facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher (JR). The Research Assistant (AL) was present for all interviews to document background characteristics. Both took field notes of verbal and non-verbal behaviours. Effort was undertaken to bracket interviewer reactions (e.g., nodding, frowning, and smiling). Reference Tufford and Newman48 The Theoretical Domains Framework, a review of the literature, and expert input informed the semi-structured interview questions (Table 1).

The interview script was pilot-tested for language and clarity by two individuals from the complex Kawasaki disease roster. No amendments were required. At the end of the interview, key points were summarised with each participant for validation and to provide an opportunity to offer any additional commentary. Interviews were audio-recorded, then transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy (JR, AL). All data were stored on a password-protected computer within the hospital’s Microsoft OneDrive and could only be accessed by the study team. Participant data were de-identified using a unique study identifier and was stored in the Master Logbook on the Microsoft OneDrive that linked the participants’ names with their alphanumeric identifier.

Results

Every attempt was made to assure maximum variation including those with disparate characteristics such as cultural diversity, geographical distance from the clinic, age, and gender, among other variables. For most reported qualitative studies exploring patient experiences, saturation is usually achieved at approximately 7–12 participants. A directed content analysis method was used, Reference Hsieh and Shannon44 “directed” per the elements of the Theoretical Domains Framework. All data were read multiple times by three researchers (NC, JR, and AL) who individually selected common terms (code words) that represented key terms and exemplars that were organised within the Theoretical Domains Framework categories. Discussion and consensus served to develop the themes that emerged; several categories were merged. Two additional categories were added to describe the personal experience of transition and recommendations for comprehensive health care transition programme development. Descriptive exemplars were selected and identified by alphanumeric labels (P1, P2, etc.).

In total, 15 young adults were eligible to participate and 4 were not eligible. Of the 15 eligible, 11 young adults consented to participate and were interviewed for the study. The other 4 were either unable to be contacted (3) or could not participate due to a critical family illness (1). Saturation was observed by the eighth participant; however, three additional interviews were conducted to assure the strength of the saturation. The Theoretical Domains Framework elements describe the processes necessary for change and independent self-care (Table 1). The elements of knowledge, emotion, beliefs, consequences, social and physical/environment combined to identify the capacity, motivation, and opportunity for independent self-care management.

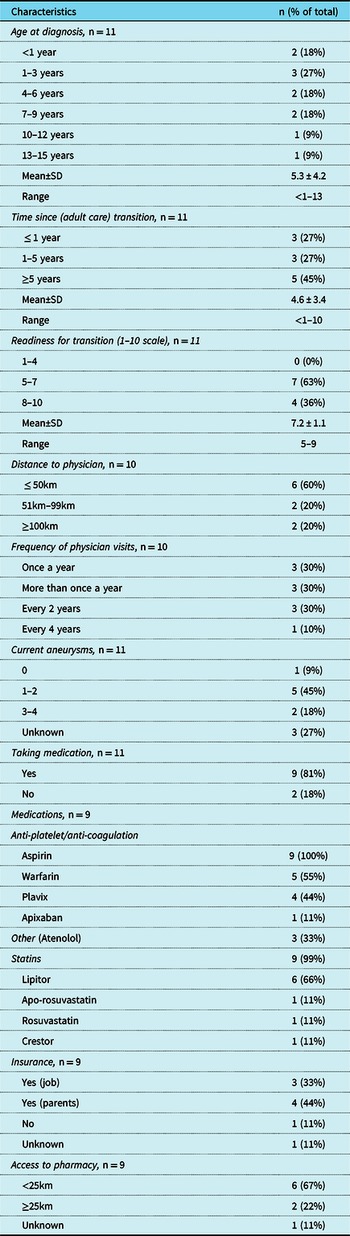

Participant background characteristics are described in Table 2. Their mean age was 22.4 ± 3.5 years (range, 18–28), and 8 (73%) were male. Almost half (45%; n = 5) reported Caucasian, while the others had varied ethnicities (Indigenous [1], Southeast/west Asian [4], and mixed ethnicity [1]). Most were single with no children, and one was living with a partner. Participants mostly lived in urban locations (n = 8, 73%), were living with parents (n = 5, 55%), and had a modest annual household income. All had completed high school and six were in college or university, with four having completed college or university programmes. Among those who stated either still being in school or have completed school, five (45%) were employed full-time, five (45%) were full-time students, and one (9%) was both employed and a student.

Table 2. Participant demographic characteristics (n = 11).

Self-reports of clinical and other relevant data were documented (Table 3). The mean age at the time of Kawasaki disease diagnosis was 5.3 ± 4.2 years (range, <1–13 years). The length of time since transition varied from 1 to 5 years. Ten participants (90%) had a physician that they regularly visited either once a year (30%, n = 3/10), more than once a year (30%, n = 3/10), every 2 years (30%, n = 3/10), or every 4 years (10%, n = 1/10). Over half (60%) were ≤ 50 km (60%, n = 6/10) away from their physician, while the rest were much further (were 51 km – >100 km) from their specialist. Over half (63%, n = 7/11) reported currently having one or more known aneurysms, one reported no known aneurysms, and 27% (n = 3) were unaware of any current coronary artery aneurysms. While all had been discharged from paediatrics with medications as listed, only nine were taking medications at the time of the interview. All but four had insurance for their prescription medication(s). Access to a pharmacy for medication(s) was mostly < 25 km from their residence (67%, n = 6/9).

Table 3. Clinical and other relevant characteristics*.

* All but one participant attended the same paediatric hospital and was referred to the same adult hospital.

Theme 1: knowledge, skill, capability, and readiness – “I take care of it”

These categories as combined from the Theoretical Domains Framework reflected their knowledge of Kawasaki disease, and their intent and capacity to maintain their health. All participants knew their diagnosis of Kawasaki disease, and most reported their specific complexities (aneurysms, treatments, past surgeries, and medications). Taking their medications was variously described by terms such as “habit,” “routine,” and “second nature.” The following are exemplars:

“It’s almost like you’re in long-term care treating cardiac disease…something you grow into.” (P1)

“My routine is 3 things [night-time routine] remove contacts, take meds, brush teeth.” (P2)

“I have aneurysms…meds are a habit, second nature kind of a thing…autopilot.” (P4)

“It’s my thing. I take care of it.” (P10)

“You have to hold yourself accountable…[Kawasaki disease] never got in the way.” (P1)

“I advocate for myself.” (P5)

“I’m 100% motivated to stay on my medications.” (P4)

Theme 2: readiness - ready but reluctant

Readiness for health care transition precedes motivation. During each interview, the participant was asked the question: “On a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means you were definitely not ready for health care transition and 10 means you were absolutely ready, what would be your number?” No participant answered “10” (Table 3), rather their answers ranged from 5 to 9 (mean 7.3). One participant initially answered 8/10, but after reflection, stated “in reality it was really a 2.” One who responded 6–7/10 said “generally, I think I wasnʼt ready because I have been at [pediatric hospital] for years… it was going to be a whole change in my life.” Another participant said “I was getting to an age when I was ready to graduate to an adult hospital [but] my parents’ grasp of the situation was stronger.”

Theme 3: consequences and emotion – it’s the hand you’re dealt with

In line with knowledge and capability, the participants were asked about what would happen if they did not manage their condition or did not attend the adult care appointments. Several noted the possibility of accident or illness:

“Clots.” (P1)

“Heart attack or stroke…it’s good to know what I should stay away from.” (P3)

“If I wasnʼt on meds, my blood would get thicker.” (P4)

“I’m conscious of my body and what happens if I drink or cut myself while on blood thinners.” (P7)

“I know to do cardio to keep my heart healthy.” (P10)

“I know I will have issues when I am older…things start breaking down.” (P8)

Emotional aspects and their state of mind when faced with health care transition were considered when asking about having complex Kawasaki disease and their loss of the family-centred paediatric clinic, as illustrated by the following:

“It’s the cards you’re dealt with…you just gotta roll with it.” (P1)

“It is what it is…I know I’m starting with a bad hand.” (P8)

“Kawasaki Disease doesnʼt hold me back.” (P7)

“I always have a looming fear in the back of my mind.” (P5)

“I focus on gratitude. I enjoy what I have and am grateful for the moments [I have].” (P11)

“I was sad to go [to adult care] …I grew attached…I had a great relationship… [pediatric hospital] knew what was going on all the time.” (P1)

“I miss [pediatric hospital] … I still stay in touch with [Nurse Practitioner].” (P2)

Theme 4: social influence and support – i look normal. Mother is key

While most participants shared their diagnosis with long time or new friends, they withheld disclosing their diagnosis unless necessary per the following:

“I donʼt tell new people unless there’s something I cannot do … I’ve always told my friends donʼt play scary tricks on me…I had to explain why I couldnʼt go to a [paintball] party this week.” (P6)

“Having [Kawasaki disease] is an easy way to refuse drugs, like it shuts down peer pressure…I only would tell if it came up.” (P3)

“Friends know but it’s a non-issue to them because I look completely normal, and I act completely normal to them.” (P9)

“I donʼt usually wear it on my sleeve [Kawasaki disease] when I first meet people…usually people donʼt know … they canʼt tell.” (P11)

In contrast, one participant stated, “I donʼt keep quiet about it…I like to spread the word” (P5).

The predominant response when asked about supportive and influential people was “mom” or “family.” Mothers typically accompanied the participant to clinic appointments and managed the administration of medications, ordering or picking up prescriptions, kept track of appointments, transportation to the clinic, and rendered support during tests or operative procedures. Following high school, many secured paid jobs, engaged in further education, and/or moved away from home; all transitions in themselves. While some embarked on an independent role in managing their condition, some continued to rely on their mothers. After mothers, other supportive people included their family, close friends, family doctor, intimate partner, or roommates. To illustrate, the following were expressed:

“Mom is my best support…I would call Mom first if I had a problem…she pushed me to be my own advocate… Even without the [pediatric hospital] I knew my mom was there. Even my mom said [to boyfriend], sit down I need to know you’re going to protect my girl.” (P3)

“I donʼt call the pharmacy on my own.” (P2)

“Mom would advocate for me.” (P5)

“My mom is my reminder… she and my family would guide me with adult transition.” (P6)

“My family is 100% my biggest support…parents remind me about my meds…I would go to the family doctor if I had problems.” (P9)

“I would call my mom if I had any problems… it’s just been me and mom… mom supporting me.” (P10)

“My mom started a binder of medical information …she was keeping track. We did our own research together.” (P11)

Theme 5: behavioural regulation/resources – structure matters

Notwithstanding parental support and guidance, most desired to follow their doctor’s advice. A few identified that teens do not always adhere to the advice and others used online sources to learn or joined an online Kawasaki disease group. Four participants noted that they or their parents had searched online (“googled”) the new doctor at the adult hospital. Statements include:

“I googled the doctor to see what he looked like.” (P4)

“I googled the doctor…read up on him…I really wanted my new doctor to be like [pediatric cardiologist].” (P6)

“Knowing them, my parents probably googled [new doctor].” (P10)

“I want my new doctor to not be super stern…I follow doctors’ orders.” (P4)

“As a teen, I didn’t always adhere to the advice.” (P7)

“There’s a lot of information online.” (P9)

Theme 6: the transition experience – transition is an upheaval, i’m not a kid anymore

Multiple overlapping transitions simultaneously impacted health care transition success. Our overall aim was to learn from the participants which elements combined to achieve the capability, motivation, and opportunities for self-care and to use their information to build a Complex Kawasaki Disease Transition Program. We began by asking their opinion on the “right” age to begin health care transition discussions. Most felt that 17 years of age was appropriate for focused discussions. One felt that they were capable at the age of 15 or 16 years. Another suggested age 15 but begin in-depth discussions at the age of 17 years. Some exemplars follow:

“Start at 17…at 17 everything is changing … you’re taking on a little more responsibility, but you still had your pediatric team who was right there if you needed them.” (P1)

“Have an introductory appointment at 17, just to know what to expect… whenever I had meetings with [the Nurse Practitioner], she’d be like, when you’re 18 what are you going to do…she’d always bring up theoreticals, so I was always preparing.” (P2)

“The [Nurse Practitioner] set me up for success … but there was a process finding someone who will take you on with [request for birth control pills] and again the blood thinner issue… [the Nurse Practitioner] would ask me questions as I got older, not my mother.” (P3)

“At 17…that’s when it starts to set in.” (P10)

Discussing the actual transition experience provoked much anxiety. The participants were firmly attached to the paediatric hospital and their team and felt a strong sense of anxiety and loss following transfer of care. Adult care was different and not as expected. Terms such as “tough,” “worry,” “unsure,” “anxious,” and “difficult” threaded through this part of the interviews. Illustrative exemplars were selected:

“It was tough…expected consistency…it’s not like [pediatric hospital] …was like going from high school to university … [new doctor] always asks me if I am going to have a family and I donʼt know why.” (P1, a male participant)

“I expected a smooth transition, but everything was off.” (P2)

“It’ll never be the same as [pediatric hospital] …I will never be as well monitored.” (P2)

“Lack of communication…you seem to get forgotten.” (P3)

“[when at an appointment for MRI] …they didnʼt know a thing about me…could I trust them? …my documents should be in the system.” (P6)

“The new doctor told me it was my responsibility to call with any problem, [the doctor said] I donʼt want to hear from your parents.” (P7)

“That’s the one thing – not seeing everyone you’re used to…I was unsure what would happen.” (P9)

“I was anxious. I didnʼt have too much trouble but it’s still a maze to me [new hospital]. I even forgot the name of the new doctor…my mind has been preoccupied with other things like passing my classes.” (P10)

“Biggest struggle was with birth control…it’s a difficult process where multiple doctors didnʼt want to refer me… I felt out of place [at the new cardiology clinic]. At [pediatrics], you’re the old one in the waiting room but when I changed over, I noticed the demographics…I was in a room with all old white men…I was a female and the young one.” (P11)

“I’m not a kid anymore. It was like taking ownership over my health care and having to be an advocate for myself…a big transition.” (P11)

“There’s a lot that went wrong…like everyone in that hospital abandoned me…the moment I hopped over to the [adult hospital], everything changed…no reminders – it’s a simple thing but it would make a big difference…every time…I had to re-educate them…you’re the young one in the waiting room and everyone is going to look at you kinda weird, like oh dear, why are you here…it took a while not to be affected by that.” (P8)

Overall themes summary and participants recommendations

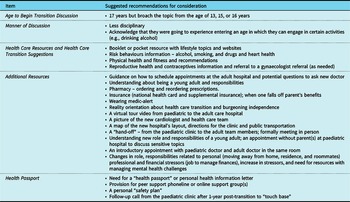

In total, there were six overall themes: I can take care of it; ready but reluctant, it’s the cards you’re dealt with; I look normal/mother is key support; structure matters; I’m not a kid anymore; and the upheaval of transition. The latter two themes related to participant recommendations for transitional programme elements (Table 4). Overall, participants were well versed on Kawasaki disease, their medical history, and current medications and knew the consequences of not adhering to their medications and limitations. One had not had an adult care appointment for 4 years. They were resolved to the notion that their condition was chronic. For most, health care transition was not a positive experience and was laced with anxiety and a feeling of being faceless or abandoned. The suggested recommendations reflected the overlapping transitions into adulthood, including lifestyle and psychosocial adaptation to both health care transition and adulthood overall.

Table 4. Participant recommendations for a Kawasaki disease transitional programme.

Discussion

With new advances in research to understand the impacts for those with complex Kawasaki disease and their families, evaluating health care transition for young adults while crucial has been underexplored. Reference Toulany, Gorter and Harrison49 According to the Society for Adolescent Medicine, the period of transition for young adults with a chronic condition involves purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults from a child-focused to an adult-focused health care system. Reference Toulany, Gorter and Harrison49–Reference Urkin, Bilenko, Bar-David, Gazala, Barak and Merrick51 This is the first known qualitative study examining the unique perspectives and experiences of young adults with complex Kawasaki disease having undergone health care transition. The results of this study indicate that it is beneficial to create a structured transition plan for adolescents that provides sufficient time to learn and emotionally prepare. Several participants expressed not being emotionally equipped to leave their paediatric team, especially relevant given their early age at diagnosis. One participant noted that their paediatric hospital was “sort of…a second home” (P7) and another reiterated that, “it is literally like my second home… I grew up there” (P8). The depth of their attachment to the paediatric centre reinforced the need for tangible reality orientation to the adult clinic. Major life transitions were occurring simultaneously, such as pursuing higher education, moving away from home, obtaining medical insurance, new interpersonal relationships, introspection, and career, among the many other challenges.

Achieving an age when the individual “graduates” to an adult hospital is a milestone. It is a critical period where new responsibilities arise. Consistent with previous studies, a major challenge among our participants was the need to create a new role for themselves that consisted of taking charge of health and lifestyle responsibilities, psychosocial management, and self-advocacy. Reference Morsa, Lombrail, Boudailliez, Godot, Jeantils and Gagnayre52 Disclosing their condition was not a priority when engaging with existing or new relationships because they looked and acted “completely normal” (P9). Contrary to previous studies conducted among youth with chronic illnesses, our study revealed that young adults with complex Kawasaki disease presented as normal and did not want to actively acknowledge their condition until withdrawing from strenuous activities, a cardiac/health-related event occurred, or until a follow-up assessment was required. Reference Ferro and Boyle53 This was represented by one of the themes (“it’s the cards you’re dealt with”) and an overall optimism for the future, whereas previous studies reported that youth with chronic illnesses had a compromised self-concept with a distinction seen in females. Reference Ferro and Boyle53,Reference Helgeson and Novak54 Despite the optimistic views expressed, there was still a sense of occasional underlying fear of morbidity. Participants’ facial and body expressions changed when they mentioned a “looming fear in the back of [their] mind” (P5) when specifically asked about any future health challenges. This further supports the notion that discussions about health care transition and the ensuing years should be viewed as an opportunity for engagement in their health, regulating their emotions, and navigating their life with Kawasaki disease. Reference Dahdah, Kung and Friedman1,Reference Kovacs and McCrindle2,Reference McCrindle, Rowley and Newburger4

Consistent with our findings, several studies exploring health care transition described that more health care transition support is needed and that acclimating to the new setting is difficult and lengthy. Reference Moons, Skogby, Bratt, Zühlke, Marelli and Goossens6,Reference Toulany, Gorter and Harrison49,Reference Hilderson, Saidi and Van Deyk55,Reference Schor56 To date, there is no consensus regarding the manner in which health care transition should be provided or organised; however, learning first-hand from young adults with complex Kawasaki disease about how we can help is positive first step. Reference Moons, Skogby, Bratt, Zühlke, Marelli and Goossens6,Reference Hilderson, Saidi and Van Deyk55 Suggestions were very similar between our male and female participants in their desire to learn more about risk behaviours. Family planning and/or contraception were expressed more with female participants. Their primary care physician, while copied on all appointment and referral letters, could be valuable in this respect; however, distance may prevent access to their usual primary care physician (e.g., moving out of the family home for education or independence) or finding a new primary care physician may be a challenge. The importance of peer support was a recommendation for managing both health care and lifestyle that were consistent with previous studies involving adolescents with chronic conditions. Reference Morsa, Lombrail, Boudailliez, Godot, Jeantils and Gagnayre52,Reference Bomba, Herrmann-Garitz, Schmidt, Schmidt and Thyen57–Reference van Staa and Sattoe60 Some of the participants expressed that talking to other adolescents (either in person, virtually, or anonymously) could have helped. A handout or “health passport” was a consistent recommendation which was previously reported as a useful resource during transition. Reference Andrade, Bassett and Bercovici61,Reference Kerr, Widger, Cullen-Dean, Price and O’Halloran62 Before transition to adult care, the sentiment of having a joint consultation with the paediatric and adult doctor was discussed in previous studies Reference Harden, Walsh and Bandler63 . Post-transition follow-up phone call with the paediatric team may help to promote psychological well-being and satisfaction with health services. Reference Colver, McConachie and Le Couteur64

Summary

This study advances our previous research and answers the research question regarding the experiences of health care transition for individuals living with complex Kawasaki disease. For this unique population, health care transition should be deliberate, well planned, and coordinated, acknowledging the importance of their developmental, academic, vocational, and psychosocial needs. This is the first known study exploring the experience of young adults with complex Kawasaki disease who have undergone transition to an adult care specialist. Our findings provided essential information required for a novel Kawasaki disease transition programme involving Kawasaki disease patients as ambassadors, one that would address the evolving personal and professional growth, self-management, health care system navigation issues, and a validation of their disease knowledge, ultimately aiming to minimise lapses in health care transition and maximise medical and psychosocial outcomes. A comprehensive health care transition programme including readiness assessment and follow-up outcomes may serve as a flagship for other regional centres across Canada and beyond.

Strengths and limitations

This study is theoretically underpinned by the Theoretical Domains Framework, and methodologic rigour was demonstrated. Several themes were identified and supported by exemplars throughout. Researcher bias could not be excluded but was mitigated by data saturation, bracketing, and triangulating results. Although the sample size and selection were appropriate for this qualitative study, the generalisability is limited to mainly a single academic centre in Ontario and was motivated volunteers. Those consenting were likely more motivated than those who did not consent to participate; thus, volunteer bias is recognised. Future directions could incorporate multiple institutions with participants from a wider variety of ethnicities. Future studies could employ clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of important components of the transition process (e.g., education and psychosocial interventions). Several participants reported virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic as a less personal when first meeting with the adult cardiologist. This may have resulted in some negative sentiments regarding health care transition. The interviews were limited to young adults with complex Kawasaki disease and did not include the perspectives of parents and health care providers, a consideration for future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the study participants, Ayan Hasan (volunteer), and Ms. Carin Lin (Kawasaki Disease Facebook administrator).

Funding support

The project was funded by the SickKids Heart Centre Innovation Fund.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at both the paediatric and adult sites involved. The study, as explained to participants, followed all principles of privacy, confidentiality, and voluntary participation. No risks or discomforts were associated with this study, and no direct health benefits to participants; however, the data would contribute to health care transition programme recommendations.