Introduction

Given that most dairy products are now industrialised, thermally treated and have to undergo sanitary inspection during processing, is it still necessary to be concerned about diseases related to consumption of dairy products? This issue is often discussed amongst food safety researchers and industry professionals, but it is not always possible to reach a consensus (O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, Sugrue, Hill, Ross, Stanton, Nero and de Carvalho2019).

In a multitude of scientific articles (over 900 000 Google Scholar search results typing ‘raw milk consumption’) it is possible to notice a remarkable convergence of ideas: the knowledge and the awareness of milk-borne infections are key requirements to decrease the risks associated with raw milk. The national regulations, the inspection service and the market surveillance are perennial strategies and cannot be neglected. However, food safety is only maximised when adopting simultaneous knowledge intensive practises. Here, we aim to clarify some relevant points related to dairy-borne diseases, providing information regarding the current scenario of the clandestine sale of raw milk and its products, in order to allow improvements in food safety.

Current relevance of milk-borne pathogens

There are three main reasons why it is still important to be aware about milk-borne pathogens. The first reason is because the sale of raw milk is regulated in some countries and direct sale to consumers is, therefore, possible. Raw milk is a product that has not undergone any thermal processing. Even milk from healthy cows, without any alterations, can still contain pathogenic microorganisms and transmit pathogens. Some of these diseases can be lethal, such as tuberculosis and listeriosis, whilst others may be incurable such as brucellosis (Claeys et al., Reference Claeys, Cardoen, Daube, De Block, Dewettinck, Dierick, De Zutter, Huyghebaert, Imberechts, Thiange, Vandenplas and Herman2013). In recent times, the consumption of bulk milk sold directly from producers was found to be associated with a higher probability of haemolytic uraemic syndrome (Ntuli et al., Reference Ntuli, Njage, Bonilauri, Serraino and Buys2018). Thus, raw milk can pose a risk to public health.

In view of this concern, the pasteurisation of milk for direct human consumption and for the production of fresh cheese is mandatory in many countries, including Australia and Brazil (Baars, Reference Baars, LA and de Carvalho2019). However, more flexible conditions are found in other countries, like USA, where some states allow the sale of raw milk, while others still prohibit such sales (Mungai et al., Reference Mungai, Behravesh and Gould2015). In some countries, such as the UK, the situation can be more permissive and raw milk can be sold directly to consumers. However, strategies in the UK to reduce risks are well established, and raw milk must be from official brucellosis and tuberculosis-free herds (Abernethy et al., Reference Abernethy, Upton, Higgins, McGrath, Goodchild, Rolfe, Broughan, Downs, Clifton-Hadley, Menzies, de la Rua-Domenech, Blissitt, Duignan and More2013). In addition, such milk must carry a health warning and can only be sold by registered milk producers or by milk roundsmen.

Can such permissive behaviour have an impact on consumer health? Prior to the 1950s, about a quarter of all foodborne infections were associated to milk consumption. Following the introduction of regulations recommending milk pasteurisation, milk was attributed with less than 1% of reported outbreaks of foodborne diseases (Mungai et al., Reference Mungai, Behravesh and Gould2015). However, in recent years this figure seems to be increasing as more countries have allowed the legal sale of raw milk. For example, in the USA the average number of outbreaks linked to raw milk each year was four times higher from 2007 to 2012 than from 1993 to 2006. Furthermore, the percentage of outbreaks associated with raw milk increased from 2% (2007–2009) to 5% (2010–2012) (Mungai et al., Reference Mungai, Behravesh and Gould2015). The infection risks associated with the consumption of raw milk are clear and undisputed; throughout history, mandatory pasteurisation has been linked with decreased numbers of outbreaks of milk-borne pathogens (Alegbeleye et al., Reference Alegbeleye, Guimarães, Cruz and Sant'Ana2018).

The second reason to continue to be vigilant about milk-borne pathogens is that even where governments restrict legal sales, raw milk and its products can be purchased clandestinely, such as in street markets or from roundsmen (Paraffin et al., Reference Paraffin, Zindove and Chimonyo2018). Compared to places where the sale of raw milk is regulated, the clandestine market poses more risks to public health because such locations are not checked by official inspection agents. In such locations there is no guarantee of food safety. In addition to the diseases that can be transmitted, these products may also be fraudulent (Tibola et al., Reference Tibola, da Silva, Dossa and Patrício2018). These frauds are economically motivated and may breach the rights of consumers regarding the authentic purchasing of dairy products. Examples of this include adding water to increase volume and chemicals to preserve their shelf life, selling milk as belonging from one species when it is actually produced by another, adding non-dairy fats, and so on (Tibola et al., Reference Tibola, da Silva, Dossa and Patrício2018). Consequently, clandestine dairy products are highly likely to be adulterated

The third reason to continue to be aware of milk-borne pathogens relates to the consumers themselves. Why do consumers continue to buy these products? Is it due to a lack of information? Because of the flavour? A lack of choice? The price? A mistrust of industrialised products? The most commonly cited motivations behind the consumption of clandestine dairy products are the taste and the purity of such products (Buzby et al., Reference Buzby, Hannah Gould, Kendall, Jones, Robinson and Blayney2013; Raymundo et al., Reference Raymundo, Bersot and Osaki2018; Waldman and Kerr, Reference Waldman and Kerr2018). However, the motivations that might drive European are not necessarily the same as for Americans, but are strongly influenced by culture. Socio-cultural aspects, such as regulatory history, cultural norms, socio-economic status, perception of health and risk and even social justice, also contribute to individual and population preferences regarding raw milk consumption (Meunier-Goddik and Waite-Cusic, Reference Meunier-Goddik, Waite-Cusic, Nero and de Carvalho2019).

There has been much popular discussion about the risks and benefits derived from the consumption of raw milk, but all current scientific studies and reviews have categorically concluded that there is no evidence that raw milk has any inherent health or nutritional benefits that outweigh the risks associated with its consumption (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Brett, Kelton, Majowicz, Snedeker and Sargeant2011). Thus the idea that raw milk might be a super food is misplaced (Alegbeleye et al., Reference Alegbeleye, Guimarães, Cruz and Sant'Ana2018).

It should be stressed that consumers receive information and make purchasing decisions based on non-scientific criteria, without consideration for factors such as safety and risk (Jay-Russell, Reference Jay-Russell2010). In a recent study, about 17% of raw milk samples tested positive for antibiotic residues, and over 21% were found to be adulterated with water, which contradicts the concept that clandestine raw milk is pure and without chemical modifications (Ondieki et al., Reference Ondieki, Ombui, Obonyo, Gura, Githuku, Orinde and Gikunju2017).

Main threats associated with raw milk and its products

The consumption of raw milk and its products may pose risks to the health of those who consume them, so much so that warning labels are required on raw milk sold in some countries such as UK and some U.S states, such as California. However, what are the risks of using raw milk and its products as ingredients in thermally processed food, such as bread, cookies, cakes and other baked goods? If milk and its products are obtained from the clandestine market, then the hazards and risks are those mentioned above. These issues can result in low quality products, low yields, microbiological fermentation failures due to possible antibiotic residues and taste defects (Fleischer et al., Reference Fleischer, Metzner, Beyerbach, Hoedemaker and Klee2001; Novés et al., Reference Novés, Librán, Licón, Molina, Molina and Berruga2015). These taste defects may be of microbiological origin, caused by bacteria that produce proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes, and/or physical factors such as oxidative rancidity caused by exposure to light (Cadwallader and Singh, Reference Cadwallader, Singh, McSweeney and Fox2009).

If raw milk and its products are obtained from the formal market, then the problem of adulteration is minimised. However, there will still be microbiological risks. As an example, a monitoring survey of raw milk sold through vending machines in Italy from 2009 to 2011 found that of the 618 samples tested, 1.6% were positive for Listeria monocytogens, 1.5% for Campylobacter spp., 0.3% for Salmonella spp. and 0.2% for E. coli O157 (Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Barbaro, Gallina, Vitale, Chiavacci, Caramelli and Decastelli2013). It is important to highlight that all samples came from health and vaccinated herds and the selling vending machines were in accordance with the enactment of an Italian law that allows the sale of unpacked and unpasteurised cows milk on the farm and at markets. More recently (2016), an outbreak with 69 cases of campylobacteriosis was linked with raw milk from vending machines in England (Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Inns, Aird, Swift, Astbury, Forester and Decraene2020). These findings raise the question of whether some national regimes for unpasteurised milk are fit for purpose.

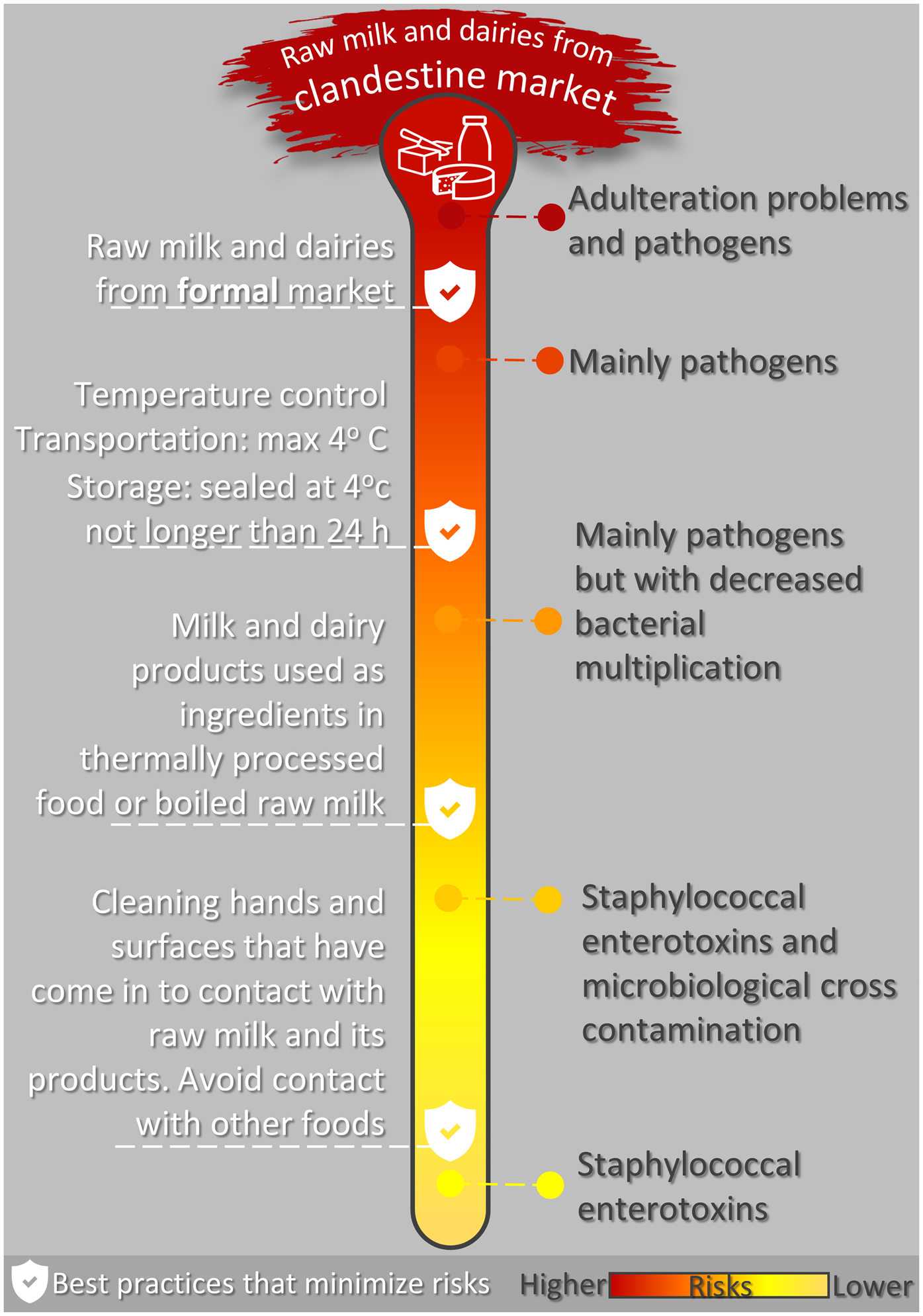

Due to the influence of the food matrix on the viability of bacterial pathogens, the dairy products most commonly involved in milk-borne infections are raw milk, fresh cheeses (without maturation) and fatty products such as cream and butter (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Jiang and Gobius2018). Despite the fact that most cooked foods usually uses temperatures higher than 180 °C there are still three basic threats: staphylococcal enterotoxins, Brucella spp. and cross contamination. Figure 1 summarises the main health risks associated with raw and dairy products.

Fig. 1. Main threats associated with raw milk and its products and effective guidance strategies to reduce them.

Staphylococcal enterotoxins

The vegetative cells of all pathogenic microorganisms are completely inactivated during pasteurisation. Various times and temperatures can be used to ensure safety, the most common being 72–75 °C for 15–20 s or 62–65 °C for 30 min. Boiling raw milk ensures the safety of the product from this point of view (Tremonte et al., Reference Tremonte, Tipaldi, Succi, Pannella, Falasca, Capilongo, Coppola and Sorrentino2014). The remaining problem lies in the presence of staphylococcal enterotoxins, that are resistant to boiling and pasteurisation. They are only inactivated at 120 psi for twenty minutes, and this condition can only be achieved using autoclaves. When ingested, staphylococcal entorotoxins cause staphylococcal gastroenteritis, a rapidly evolving type of food poisoning (from thirty minutes to six hours after the ingestion of contaminated food), as well as clinical symptoms of nausea, vomiting, headaches, abdominal pain and diarrhoea (Artursson et al., Reference Artursson, Schelin, Thisted Lambertz, Hansson and Olsson Engvall2018; Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2019).

Brucella spp.

Cream and whipped cream are widely used in food services, whether for making Chantilly, to cover cakes, in ice cream, for creamy fillings, etc. Cows, goats and sheep that are infected with brucellosis excrete Brucella cells in farmed milk with no visible alterations (LeJeune and Rajala-Schultz, Reference LeJeune and Rajala-Schultz2009). These microorganisms have an affinity for milk fat globules, and the dairy derivatives that pose the greatest risk are cream and whipped cream. The higher the level of fat, the greater the risk of transmission. This problem is enhanced because the cream is not usually baked with the dough, resulting in the continuing presence of viable cells in these products (Kaden et al., Reference Kaden, Ferrari, Jinnerot, Lindberg, Wahab and Lavander2018). Brucellosis is an incurable chronic disease that causes arthritis, meningitis, endocarditis, orchitis, fevers and night chills (Doganay and Aygen, Reference Doganay and Aygen2003).

Cross-contamination

This threat is related to failures in the food safety procedures and may only occur when a pathogenic microorganism is present. In this case, raw milk and its products can be sources of contamination in food services and industrial kitchens. Some pathogenic cells, such as L. monocytogenes, can spread to all surfaces through cross-contamination. The frequency of this microorganism in milk is considerable: of 861 samples of raw milk, almost 7% contained L. monocytogenes (Van Kessel et al., Reference Van Kessel, Karns, Gorski, McCluskey and Perdue2004). Furthermore, this microorganism has adapted to stainless steel surfaces, where it can set and form biofilms (Herald and Zottola, Reference Herald and Zottola1988; Oliveira et al., Reference Oliveira, de Brugnera, Alves and Piccoli2010). Even in industrial plants with excellent levels of cleaning the occurrence of L. monocytogenes is 7%; in places where cleaning is deficient the occurrence can reach almost 28% (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Jensen, Kinde, Alexander and Owens1991). Listeriosis is a disease of high mortality but low morbidity: immunosuppressed people are most affected. In addition to causing death, listeriosis also causes miscarriages, arthritis and encephalitis; in its non-invasive form it can result in gastroenteritis.

Another aetiological agent of foodborne diseases linked to dairy products is Campylobacter jejuni (Paramithiotis et al., Reference Paramithiotis, Drosinos and Skandamis2017). Over the past decade this pathogenic bacterium has been detected worldwide in raw milk. Recently, almost 12% of raw milk purchased from individual suppliers were positive in Poland (Andrzejewska et al., Reference Andrzejewska, Szczepańska, Śpica and Klawe2019). In New Zealand, Campylobacter is the most common pathogen reported in association with raw milk-related disease outbreaks (Davys et al., Reference Davys, Marshall, Fayaz, Weir and Benschop2020). The primary reason is the use of unpasteurised milk for the production of dairy products (Paramithiotis et al., Reference Paramithiotis, Drosinos and Skandamis2017).

Although pasteurisation can effectively eliminate vegetative cells (including C. jejuni) (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Carroll and Jordan2003), it should not be regarded as the only line of defence, especially since the contamination may occur during the subsequent processing steps. One of the consequences of cross-contamination is the growing number of recalls of dairy products, increasing from 4% (in 2015) to 17% in USA (2017) (Paramithiotis et al., Reference Paramithiotis, Drosinos and Skandamis2017).

Reducing the risks associated with raw milk in food services

In order to reduce the risks associated with raw milk and its products, there are five highly effective guidance strategies for food services: (1) Never buy milk and its derivatives from clandestine sources; the latter are not inspected, and in addition to transmitting pathogens these products may be adulterated; (2) When buying raw milk from legally approved sources always boil the raw milk before use or consumption, once even inspected raw products can harbour pathogenic bacteria. (3) Fatty dairy products pose considerable risks: only use industrialised cream, whipped cream and butter; (4) Clean hands and surfaces that have come into contact with raw milk and its products to minimise cross-contamination: hands and surfaces should be cleaned with soap and water and then sanitised; (5) It is essential to strictly control the temperature regarding raw milk and its products; this practice is not only linked to spoilage bacteria, but it can also minimise the presence of pathogenic microorganisms (Leclair et al., Reference Leclair, McLean, Dunn, Meyer and Palombo2019). The temperature of transport and refrigeration should never exceed 4 °C. Use recyclable ice and thermal containers during transport. Do not use products stored for more than 24 h, even if refrigerated at 4°C. Products should be sealed when stored, should not come into contact with other foods, and should be consumed as soon as possible. Freezing does not guarantee safety: some microorganisms such as L. monocytogenes can survive for more than 365 d in frozen raw milk (Leclair et al., Reference Leclair, McLean, Dunn, Meyer and Palombo2019). Figure 1 summarises the main strategies discussed above.

However, knowledge is the best way to reduce the risks associated with raw milk and its products. A recent study concluded that the ability to understand the risks associated with the consumption of unpasteurised dairy products was linked to the health status of the population. We found that consumers who are aware of milk-borne pathogens were twice as likely not to have abdominal pain. For the first time, it was observed that the awareness of milk-borne pathogens provides benefits for consumer health and is a protective factor in relation to abdominal pain (Fagnani et al., Reference Fagnani, Eleodoro and Zanon2019).

Other examples also show a positive association between general knowledge and health status. Mosalagae et al. (Reference Mosalagae, Pfukenyi and Matope2011) stated that by improving the level of awareness for zoonoses, teaching and training of population, both human health and food safety could be enhanced. In addition, Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Hillers and Thomas1999) also concluded that educational workshops were a successful food safety intervention to reduce the incidence of Salmonella Typhimurium associated with eating fresh cheese. This leads us to reinforce that knowledge can promote health-seeking behaviour and good health, as reported by Aaby et al. (Reference Aaby, Friis, Christensen, Rowlands and Maindal2017).

More recently, a study conducted in Tanzania evaluated how narrative and technical risk and health messages impacted the hygiene practices and the milk quality in a pastoral community (Caudell et al., Reference Caudell, Charoonsophonsak, Miller, Lyimo, Subbiah, Buza and Call2019). The results suggest that the use of narrative messages can promote healthy behaviour even when cultural norms are contrary to best health practices (Caudell et al., Reference Caudell, Charoonsophonsak, Miller, Lyimo, Subbiah, Buza and Call2019). In low income and/or developing countries there is a strong association between educational level and the knowledge of the population on milk borne zoonosis (Mandefero and Yeshibelay, Reference Mandefero and Yeshibelay2018). These regions face challenges to increase the educational level of the whole population, and consequently reduce the incidence of diseases assocaited with raw milk consumption (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Dahia, Yadav, Kumar and Tomar2017). However, it is common to find people aware of the raw milk consumption risks in developed countries, but still consuming raw milk. Here, the challenge is not only to increase the awareness about milk-borne infections, but to understand why the health risks are ignored by this segment of the population. Then, the strategies to promote knowledge should be in line with the demographic condition. Not only milk-borne diseases but any dietary-related condition are more easily preventable if consumers understand the factors that support their dietary choices.

Regardless of whether a country regulation allows or prohibits the trade of raw milk and its products, knowledge of the risks associated with these products is critical to assure the population health. Consumers should be kept informed and alerted regarding this issue, whether via product labels, through advertising campaigns promoted by official inspection and regulatory offices or via university outreach programmes. In addition, it is clear that this is not the time to be negligent regarding raw milk and its products because of the health risks that they represent, especially those that are purchased clandestinely.

Future progress

As in other areas, knowledge is the key to promoting health. But how to achieve it? Traditionally, it can be achieved by ongoing and continuous training of food handlers. Each food sector should develop specific didactic and pedagogical techniques providing realistic examples (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Lemos, Silva, Hora and Cruz2014). Not least, teaching and training of the population is also essential to strengthen awareness for better food safety. But first, studies about the demographics, perceptions and behavioural attributes of consumers can be helpful in targeting educational efforts and better strategies on consumer education.

In the absence of massive scientific dissemination in this area, it is very likely that distorted information can be spread easily through the population, mainly through the web and social media platforms. However, false information would be ineffective if readers were able to identify it as such. Thus, the exteriorisation of regulations, science and technology out of its own sphere of production is a key requirement for better food safety. The university, organised civil societies, and mainly the government, can bridge the gap between trusted information and society at large through scientific dissemination to ensure a better understanding of food safety (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Yuelu Huang and Manning2019).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.