Introduction

This action research project investigates the effects of the use of ‘free composition’ in the teaching of Latin to a group of Year 10 pupils. By ‘free composition’ I mean pupils were not given English sentences to translate into Latin, as is the case in many Latin course books (see, for example, Cullen and Taylor's Latin to GCSE (Reference Cullen and Taylor2016)), but were told to use simple Latin sentences to tell a story of their own devising. The focus of the study will be on analysing pupils’ perceptions of the value of free prose composition and how free prose composition can be used to analyse pupils’ understanding of grammatical features by investigating the types of errors which they made.

One of the reasons to focus on the teaching of prose composition was that it has been introduced into the Eduqas GCSE examination, to be taken from 2018 onwards (WJEC, 2016). The Year 10 class which is the focus of the study will therefore be the first year to take this examination and its prose composition element. Although it is an optional part of the GCSE, and of the OCR A level, my placement school has opted to prepare its pupils for the prose composition section in both instances.

A personal reason for pursuing this line of research arose from my experience teaching Latin prose composition at university in 2015-16. The course taught classicists with Latin A level, or those who had taken the university's beginner's Latin course. The course used Bradley's Arnold, a 100-year-old textbook. My experience of teaching from its antiquated English to Latin sentences and feedback from students who found the sentences they were being asked to translate opaque in meaning has prompted me towards this line of study.

The school is a non-selective girls’ school, rated as outstanding with very high levels of attainment with Ofsted noting that ‘the proportion of students gaining five A* to C grades including English and Mathematics has increased and is very high’ (Ofsted 2013, 4). ‘The large majority of students are of white British heritage and speak English as their first language’ and ‘The proportion of students who are eligible for the pupil premium is below average’ (Ofsted 2013, 3). In 2016, the school achieved a Progress 8 score of 0.6 which is well above the national average (UK Government, 2016)Footnote 1. The school has a successful Classics department. Uptake for Latin at GCSE is high. In the current Year 10 there are two classes: the one to which this sequence of lessons was taught has 13 pupils of varied prior attainment, with five pupils working at GCSE Level 8 or higherFootnote 2.The Year 10 Latin class was chosen for this project as they are in a unique position within the school regarding their experience of prose composition. Since the reformed GCSE was announced the department has changed its approach towards teaching prose composition, making it an ongoing focus from Year 7 onwards that the pupils should be able to manipulate Latin or write in Latin. However, this means that that current Year 10 class has not had the same preparation for the prose composition element of the exams as pupils who are moving through the lower years now. Most pupils in the class had limited experience of prose composition except for one pupil who had done a considerable amount of work on it during independent learning.

Literature Review

Prose Composition in Latin

Let us consider the reasons we have for teaching pupils to write in Latin. Firstly, it is required by the examination bodies. The WJEC exam board has a five per cent optional component of its GCSE examination based upon translating three short simple sentences from English into Latin (WJEC 2016, p. 2). When it comes to other reasons for asking pupils to write in foreign languages, we look at the rationale given for writing in modern foreign languages. In modern foreign languages, writing makes up a greater part of the assessment than in Latin and more weight is therefore given to the teaching of it. For GCSE French, following the AQA specification for example, pupils are asked on their written paper to answer three questions. The first two of these, worth 48/60 marks, require the pupils to freely compose in French with the content directed by a few introductory bullet points. The remaining 12 marks are for a direct translation from English into French. The language level expected of written French at GCSE is much higher than that expected of written Latin. Given the focus on free composition in French it will also be beneficial to consider the methods used by MFL teachers for instructing pupils in writing.

Grauberg (Reference Grauberg1997) offers three reasons for writing in a modern foreign language. Firstly, that writing reinforces learning. Secondly, that it is an important as a form of communication. Finally, that it ‘offers even to learners with limited proficiency a means of individual and sometimes quite personal expression’ (Grauberg, Reference Grauberg1997, p. 213). The second of these reasons is clearly redundant in the case of Latin. However, the first and the third of these reasons are applicable reasons for teaching pupils to write in Latin. It does, however, depend upon the manner of teaching as to the efficiency with which these reasons are realised. Teaching which demands pupils translate sentences from English into Latin provides very little room for individual self-expression. Indeed, textbooks which follow this route tend to focus only on the way in which writing in Latin reinforces understanding of the language. This is, however, the predominant means by which prose composition is taught and is the means by which pupils are assessed for composition in the GCSE examination. Following this model, the Latin prose composition textbook Bradley's Arnold argues that ‘when a student has himself [sic] employed the language as a tool, he is better able to appreciate the achievements of the great Roman writers’ (Mountford, Reference Mountford2006, p. 1). The purpose of writing here is solely focused on understanding and appreciating often highly complex language. This method of teaching leads pupils towards writing in a very literary style of Latin, which it is argued, can help with pupils’ critical appreciation of literature at a higher level. For example, Matz, asking his pupils to translate an English translation of Cicero back into Latin while competing with each other and ‘Cicero’ himself to write in the most Ciceronian style, noted a ‘steadily increasing awareness of Ciceronian prose style’ (Matz, Reference Matz1986, p. 353). But by focusing on translating from one language to another, pupils can get distracted by questions of translation rather than of composition. The reasons for choosing to use the ‘free’ method of composition, therefore, are to have the focus of the learning on the manipulation of the Latin language to create meaning so as to develop pupils’ language skills and to give the pupils some scope for self-expression which is intended to have a positive effect on their attitude to the work.

The narrow focus of the traditional manner of teaching of prose composition through translating English into Latin has been challenged as useless by Ball and Ellsworth (Reference Ball and Ellsworth1989) who base their objections to the teaching of Latin Prose Composition on four points:

1. Prose composition is a purely intellectual challenge.

2. It is elitist and scares off the less capable students.

3. Writing does not aid reading. Composition is not taught in small chucks.

4. Exercises should aid recognition of forms not their production.

They further argue that while prose composition can be taught to older pupils to teach more grammar, it cannot aim to recreate a given author's style (Saunders, Reference Saunders1993, pp. 385-6). There are ways of teaching prose composition which are guilty of these criticisms. But is it the manner in which it is taught, rather than the thing itself which is open to this criticism?

In designing this prose composition project, therefore, the aims have been informed by these criticisms. This project therefore aims to make Latin composition:

1. More than an intellectual challenge and into an opportunity for self-expression and creativity;

2. Accessible to students of all abilities by careful scaffolding for the weakest pupils and encouragement for pupils of higher ability to stretch themselves into using more complex grammar; and

3. An aid to pupils’ recognition of form by providing them with the forms, in table form, and asking them to use them in an appropriate context.

Free Composition

By ‘free’ composition I mean that pupils produce Latin not by direct translation from English into Latin. A compelling argument in favour of ‘free’ composition is put forward by Minkova and Tunberg (Reference Ward, Minkova and Tunberg2004) in their textbook Introduction to Latin Prose Composition:

We believe that learners who must think in Latin when they compose will acquire the ability to compose Latin more rapidly and effectively than those who are asked to convert thoughts communicated in another language into Latin words and phrases (Minkova and Tunberg, 2004, p. v).

This approach therefore allows the pupils to focus exclusively on improving their understanding of the Latin language rather than English. Minkova's textbook offers a range of exercises in free composition:

We may rework texts by asking questions and then answering them; by making a summary of the text and trying to find a good Latin title for it; by simplifying compound complex sentences into simple sentences or vice versa; by explaining the text in Latin using synonyms and different grammatical constructions; by rendering an implicit dialogue explicit; by converting poetic language into prose etc. (Minkova, Reference Minkova2009, p. 123).

These reworking activities are good as they ask for a response to a piece of Latin. This means that pupils must be practising their reading skills in the first instance. Pupils then also have much of the vocabulary and sentence structures in front of them which they can use to rework in their answers. However, comprehension answers and summaries are again limited in the amount of self-expression available.

At the end of each chapter there is a brief series of exercises in free composition. These exercises are quite unconnected with the readings in each chapter, nor do they necessarily relate to the grammatical principles highlighted in the chapter. The purpose of these exercises in to offer the learner a brief change of pace, an opportunity for greater freedom of expression, a chance to deploy not only imagination, but whatever resources of language s/he may have acquired up to that point (Minkova & Tunberg, 2004, p. vi).

These activities do therefore offer the sought ‘freedom of expression’ but the disconnect from the text read is an opportunity missed for allowing the pupils to recycle their vocabulary into the work. Minkova (Reference Minkova2009) outlines some other creative options:

A free composition may be a narration of historical facts, a character portrayal, a moral or philosophical treatise, an accusatory or a defensive speech, an autobiographical piece, a letter etc. (Minkova, Reference Minkova2009, p. 131).

Depending on the grammatical focus of the teaching some of these genres are more suitable than others. For example, letters require the use of 1st and 2nd person forms while historical facts would use 3rd person forms. Character portrayal requires descriptive language so could be the product of lessons focusing on adjectives, relative clauses and participles.

There is, however, a possible counterpoint to using free composition, related to pupil attitude. This was identified in a study which looked at an approach to writing in MFL which promoted creativity (Morgan, Reference Morgan1994). Schools in Cambridgeshire ran a creative writing project where pupils were encouraged to write poetry in other languages. This approach ‘moves beyond simply viewing poetry as a catalyst for communication in the foreign language and values creative writing in its own right’ (Morgan, Reference Morgan1994, p. 44). Pupils were given pictures or music as stimuli and wrote a creative response in another language. Two attitudes towards asking pupils to be creative which are identified: either it is a source of pleasure for pupils or pupils can find it alienating when they struggle with being creative. It will therefore be important in this study to monitor pupils’ reactions to being asked to be creative at the same time as writing in Latin.

Prose Composition – Designing the project

In order to design a series of activities to teach prose composition using the ‘free’ method I reviewed a number of pieces of literature in which other school teachers or university lecturers outline methods they have used and provide some analysis of them.

The most influential piece is that of Davisson (Reference Davisson2000). Their project asks pupils to rewrite a Latin passage from a different point of view. Initially pupils produce ‘seven or eight sentences, each beginning with the subject and ending with an indicative verb…When this draft has been corrected, students are given a list of “sophisticated” constructions and techniques, of which they must incorporate at least three…into their second draft. This usually contains about six slightly more elegant sentences instead of eight very simple sentences. In the third and/or fourth drafts, students play with word order for emphasis, insert transitions (igitur, relative pronouns, etc.), and add some rhetorical flourishes’ (Davisson, Reference Davisson2000, p. 4). The competency of the pupils who Davisson teaches is considerably above the Year 10 class in question so the core learning will be focused only on the limited forms required of the examination specification. However, extension work to push higher-attaining pupils will be designed using the redrafting process.

As a source of inspiration for their writing Davisson asked pupils to respond to a story written in Latin, for example the ‘Judgement of Paris…thus, the student should not be tempted to look up quantities of words or to invent many idioms’ (Davisson, Reference Davisson2000, p. 4). These reasons for responding to a Latin story were accepted and formed the basis of what pupils were asked to do in the lessons. Other studies also point to the importance of limiting vocabulary for pupils. For instance, teaching composition at a university-level course in America, Lord (Reference Lord2006) uses famous modern-day speeches and poems, such as Churchill's ‘We shall fight them on the beaches…’ oration, as the source of prose composition exercises. A problem Lord acknowledges with this approach is that it ‘sacrifice[s] the repetition of familiar vocabulary which can be beneficial to learning’ (Lord, Reference Lord2006, p. 4). Lord mitigates this by glossing rare words, but this adds to the difficulty of the activity. Based on this I decided to limit the vocabulary pupils would use. A possible way of doing this was suggested by Beneker (Reference Beneker2006). In this case pupils were first asked to compose in English using a controlled vocabulary and then translate their composition into Latin in stages correcting mistakes and adding complexity at each step. Assessing two samples of English essay which were produced, Beneker notes the generic nature of Sample 1 which draws on the same themes and characters as the course book. But there is a strong element of self-expression in Sample 2 which addressed and offers a personal response to contemporary world events at the time. Here is an example of pupils reacting with different types of responses to the greater level of freedom offered to their compositions. It was noted that ‘many of the students were clearly satisfied by having expressed original ideas in a foreign language’ (Beneker, Reference Beneker2006, p. 7). This suggests that there is generally a positive student response and increased engagement by students when they have the opportunity to self-express their creativity in their compositions. Beneker (Reference Beneker2006) identified that the process of translation was still initially daunting. A systematic approach to translation was explained in the classes and students who followed it were the ones who did well. In future, all pupils would be required to show their working through this process as well as a final result (Beneker, Reference Beneker2006, p. 7). This suggests the importance of providing a heavily scaffolded approach to the composition exercises and requiring all pupils to follow it. Another suggestion to incorporate into the study was peer reviewing of each other's translations. This was influenced by the work of Matz (Reference Matz1986). Pupils in this study translated English translations of Cicero back into Latin and then compared their products with each other and with Cicero's original. This idea of pupils evaluating the Latin of their peers for accuracy was taken on and incorporated into the project.

In order to prepare pupils to make their composition some further steps were identified as being beneficial. After the first class was taught it became clear that pupils needed further guidance on crafting forms of verbs or nouns needed when translating. The literature suggested a number of ways this could be done to aid in the pupils’ final compositions. Kavanagh and Upton (1994) detected in their research a three-step process to developing pupils’ writing abilities in foreign languages

(1) writing to learn: copy writing, note-taking, gap-filling;

(2) writing to a model: adapting a model text, working from one text type to another;

(3) learning to write: creating one's own texts suited to purpose and audience (Kavanagh and Upton, 1994).

What was needed then was some preparation exercises from step one. Davisson used a range of familiar transformation exercises such as taking ‘Latin-to-English sentences…translated in class and change[ing] the number, substitute different vocabulary items, etc.’ (Davisson, Reference Davisson2000, p. 2). Grauberg (Reference Grauberg1997) suggests gap fills as a way of consolidating grammar and vocabulary and which have value ‘whether the gap is to be filled with a verb form or an adjective’ as ‘it is part of a sentence and thus within a context’. The task can be made easier by ‘naming the alternatives, limiting them to two etc.’ (Grauberg, Reference Grauberg1997, p. 218).

From step one of Kavanagh and Upton's (1994) process pupils are then to move to step two where they are to be asked to respond to a model story. At this point pupils will ‘write whole sentences or short texts themselves. At the start such writing will not only be closely based on previous…work, but the actual content of what is to be written will be guided and choice limited. Guidance can be given through…written models’ (Grauberg, Reference Grauberg1997, p. 219). Pupils would be reading and responding to a Latin story and this was to provide the model for their answer. The ultimate product which pupils were to be asked to compose would be a text which was a response to a story in Latin:

What matters is that one should be clear about the meaning of the phrase ‘creating a text’. It is not a question of inventing something, for pupils will be using words and phrases learnt during their course, sequencing them according to the established patterns and rules of the language, perhaps just adapting models, as was shown earlier. Nor is it a question of using language in a novel or unusual way, let alone producing a poem or a literary text… It is simply a question of making a personal choice about what to write, and trying to ensure that whatever is written, however commonplace, makes sense (Grauberg, Reference Grauberg1997, p. 220).

That the text the pupils wrote ‘makes sense’ would therefore be the main assessment criterion used for judging pupils’ ability to write in Latin successfully.

Research Questions

Based on my knowledge of the class and informed by the reading undertaken, the research questions (RQs) investigated hereafter are:

RQ1. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition lead to an greater level of engagement in the process of learning to compose in Latin? This research question will be addressed by looking at how pupils valued the experience of writing in Latin in this way.

RQ2. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition produce a high level of accuracy in pupils’ work? This research question will be addressed by looking at the pupils’ written work for understanding of morphology and syntax.

Teaching Sequence

The teaching sequence was carried out over three lessons. In the literature review the importance of having material for pupils to respond to was identified. It was decided to use a set of stories from the class course textbook, the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC), as the response material in order that pupils would be familiar with the content and vocabulary. In choosing which set of stories to use there were a number of considerations. Firstly, the Latin had to be simple enough that the pupils would be encouraged to mimic its structure in their own writing. The Latin of Stage 6 of the CLC is largely of the standard that pupils are expected to be able to produce in their translations into Latin (WJEC, 2016, p. 23). By this stage, they have met the present, imperfect and perfect tenses in the third person singular and plural and they are also acquainted with nominatives and accusatives in the singular and plural. Therefore, any material after this stage would contain the core grammar that pupils are asked to reproduce in their own writing, except for adjectives. It was decided not to make adjectives a core component of the teaching but to offer them as a stretch activity for more able pupils to break down the pupils’ learning into smaller chunks.

The class had just finished studying Stage 27 of the CLC. The Latin in that Stage is a lot more advanced that what they are expected to produce and therefore was not suitable for being used as the response material. As I was keen to use stories from Book One for the standard of Latin it was important to pick a story they would remember and would enjoy reading again. The obvious choice of story, based on anecdotal feedback about the pupils’ favourite story was the final story in Book 1 at the end of Stage 12, finis, where Caecilius dies, Clemens is freed, and Cerberus stays with his master. Pupils tend to have a strong reaction to the death of the main character and especially his dog. As was discussed in the literature review the response had to be something that reworked the text, so that pupils were using familiar grammar and vocabulary, but also something that gave the pupils some freedom of expression. Pupils were therefore asked imagine the fate of Metella, under the title of mors Metellae.

It was decided to use two lessons for pupils to write their final story. In the first lesson pupils would respond to one of the earlier stories in the chapter, tremores. This story was more suitable than the other stories, ad urbem and ad villam, as the they contained a lot of 1st and 2nd person verb forms which are not part of the core learning for the examination. For the response to tremores pupils were asked to rewrite the story. This would provide a contrast with the second and third lesson in terms of pupil self-expression and engagement as rewriting requires less creativity than imagining a whole new outcome for a character.

Methodology

As this was a new way to using the course textbook it was necessary to design booklets for each composition task. Booklet One (Appendix A) covers the one lesson spend rewriting tremores and a second Booklet Two (Appendix B) covers the two lessons spent on writing the Metella story. The production of Booklet Two was influenced by the pupils’ response to Booklet One. The booklets were titled as a ‘Storytelling Project’. This was encouraging pupils to be creative with their work.

Booklet One, the tremores booklet, began with a questionnaire to gauge pupils’ perception of their enjoyment of writing in English, reading Latin, and also their ability to read Latin and write Latin.

The booklets were divided up into a series of exercises. In the tremores booklet pupils were asked in Exercise One to tackle prose composition questions of the same format and difficulty as expected in the examination. This was to gauge the pupil's aptitude for prose composition before the course began as some of the pupils had completed some work on prose composition previously in their independent learning classes. Exercise Two was a reading of part of the tremores story which the pupil would then rewrite. Exercise Three was a preparation table. This was set out in the word order that pupils were encouraged to write in: nominative, accusative, adverbial phrases, verb. Pupils were to fill in the table with the correct forms based upon some forms already given. They were then to use the table to compose their sentences by selecting the relevant forms from the boxes required. Exercise Four asked the pupils to produce a first draft in table form. Exercise Five asked the pupils to write out their story in continuous form. They were then to swap with another class member and translate each other's stories. This was inspired by a number of readings in the literature review which emphasised the importance of a feedback loop. It was also the intent that this would encourage pupils to share their rewritings of the story with one another and therefore an appreciation of each other's work.

Exercises Six and Seven ask pupils to add in adjectives, adverbs and link words to their story, without any scaffolding support offered by the preparation table. This was an extension activity designed for higher attaining pupils to complete.

At the end of the booklet pupils answered a short questionnaire to evaluate their perceived enjoyment of the lesson and the lesson's perceived difficulty.

Booklet Two was initially designed to be the same as Booklet One. However, based on the students’ use and feedback on the first booklet, changes were made. A final resource, consisting of a one-sheet table of key endings, was produced for the last lesson based on further student feedback. These changes will be discussed in the data and findings section.

The main change between Booklets One and Two was the addition of preparation exercises such as gap fills. Eight language activities were offered to the pupils, six from the CLC online activities focusing on either noun or verb endings and two sets of written activities in the booklet focused on forming nouns or verbs. In addition to this, on the front cover, was a box for pupils to keep a tally of their performance in a rapid-fire game of composition, where pupils were asked to compose sentences on the notepads on their ipads using only puella, servus, and expecto based on the teacher's orally delivered English sentences.

Another alteration in Booklet Two was a much-expanded preparation table which broke the verbs and nouns down into singular and plurals. This was in response to errors made by pupils in the first lesson, as will be discussed below.

Finally, the review element of the first draft was removed as pupils had not responded well to translating each other's work in the first lesson and it was not felt as beneficial to continue with that element.

Research Methods

The following data are used to answer the research questions:

1. an initial questionnaire taken by all 13 pupils.

2. a questionnaire at the end of the end of the first lesson taken by all pupils.

3. an end of project questionnaire taken by a self-selecting group of four pupils.

4. written work completed by pupils in their two ‘project booklets’.

5. observation notes by the class teacher.

6. observation notes by observing teacher.

Two questionnaires were used to gather data. In the first, questionnaire response scales were used. In the second, pupils answered open questions about the work they had done. One of the problems with response scales is that they are subjectively linked to individuals: one pupil's 7 might be another pupil's 5. A small number of questions were asked in each questionnaire with the hope that pupils would therefore spend a little more time thinking about their answers. The questionnaires on the whole are problematic in terms of their reliability as will be discussed further in the findings below.

Pupils’ classwork provides another source of data for this research. As the output of each pupil was unique there are fewer problems with this data being the product of group activity than might otherwise be the case. However, many of the pupils did ask the teacher for help with certain constructions during the lesson which the teacher then guided them through. Overall though these were mainly to do with writing Latin which went beyond the core learning.

Observation notes by the class teacher are only of limited use in answering the research questions. During a lesson, it much easier for any enthusiasm of the pupils to be detected and later noted than it is to recognise any apathy. A small number of pupils being enthusiastic about the work can generate an atmosphere of engagement in the classroom which is not necessarily representative of every pupil. Teacher observation notes might also ‘miss key events’ and may be ‘either much too self-critical or self-forgiving’ (Taber Reference Taber2013, 251). There is also the impact of teacher bias to be considered. Having taught a university prose composition course using English into Latin sentences and having seen low pupil engagement, I was hoping that a different approach would lead to greater engagement. Furthermore, I personally enjoy creative writing and again hoped that the same would be true for the pupils writing stories in Latin. Classroom observation was carried out by another teacher who was familiar with the class. This teacher was asked to specifically focus on observing pupil engagement in the form of free-form notes.

Data and Findings

RQ2. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition produce a high level of accuracy in pupils’ work?

In order to answer this question, the written work produced by the pupils in their project booklets was analysed to ask:

1. What type of errors do the pupils make?

2. How frequently are errors in the core learning made?

3. What causes these errors?

4. Is there something in the way the teaching was done which led pupils into making some of these errors?

One of the most common types of errors was pupils’ use of Latin with not quite the right meaning. This was often caused by the pupil not having the range of vocabulary to say what they wished or the semantic range of the English meaning of the Latin word not mapping perfectly bac k into Latin. This is a particular issue of giving the pupils freedom of expression with a language they are very raw at expressing themselves in. An example of this error is the sentence postquam tremores eum ad hortum duxit; however, the idea of the tremors leading someone to the garden is an English idiom and it does not match up with any of the uses of duco which pupil have met so far in their learning of Latin. Beyond these infelicities of expression, errors which the pupils made where assigned to two categories: core errors and non-core errors. Core errors were errors in grammar of the sort which would be tested on the GCSE Latin examination. Non-core errors were other types of error. It is primarily core errors which are discussed here. Between the two lessons the number of core errors grew from 11 to 17 and the number of total errors from 37 to 45. While some of this may be due to pupils writing more from one lesson to another some of these errors can reasonably be assigned to weaknesses in the teaching and resources used.

There were five types of core error identified:

1. errors in forming 1st conjugation verbs.

2. errors in forming 1st or 2nd declension nouns.

3. mixing up singular and plural verbs.

4. mixing up singular and plural nouns.

5. adjective errors.

In the first composition the pupils produced, in response to the tremores story, six pupils could write their first Latin story without making any core errors. These included Sian and Esme, two of the lower-attaining pupils in the class who responded well to teaching a process. The list below shows the types of core error made in the first lesson:

Error Types:

1) errors in forming 1st conjugation verbs (1 student).

2) errors in forming 1st or 2nd declension nouns (2 students).

3) mixing up singular and plural verbs (7 students).

4) mixing up singular and plural nouns (1 student).

5) adjective errors (0 students).

As can be seen the most common error was made by pupils mixing up singular and plural nouns. Seven core errors consisted of using singular verbs when a plural verb was required. For example, Adele wrote Caecilius et Iulius sacrificium ad larium fecit. This double singular subject requiring a plural verb is a more advanced concept to grasp than a single plural subject. Furthermore, the focus of the lesson had been on using singular verbs and the ‘preparation table’ in Exercise Three had only used singular forms of the verbs. Thus, the pupils did not have plural forms in front of them. The rationale behind this design was to introduce singular forms only in the first lesson and plurals in the second so that the pupils were not swamped with forms in their first lesson. Overall, this was successful and most pupils stuck to only using the singular forms they had been presented with. However, several pupils were led into writing sentences where plural forms were needed. The decision to have two people as the subject and thus require a plural verb is a stylistic choice on behalf of the pupil, but other singular-plural errors were caused by the preparation table. tremores and epistulae which are both plural nouns were given in the table for pupils to use. A note was placed below the table (Note: Plural nouns (tremores/epistulae) take plural verbs -bant/-erunt) to guide pupils with using these words and attention was explicitly drawn to it in the lesson by the teacher. Nevertheless, pupils still produced sentences which mixed up these plural nouns with singular verbs, for example: tremores terram sensit. Some of those seven core errors made by the pupils could be put down to difficulties with trying to teach singular and plural forms in separate lessons and the confusion caused by the appearance of plural nouns in the preparation table. Not all of the seven do fall into this category. For example, one high-attaining student stretching themselves wrote Iulius perterritus erant, using a verb which was not given in the preparation table.

Looking at the other errors, one of the weaker pupils in the class, Clare, wrote Iulius in horto ambulait. This error in forming a 1st conjugation verb was traced back to the preparation table where other incorrect forms such as dictait and legeit were present. This suggests that some of the weaker pupils required greater scaffolding when forming Latin verbs and nouns. A look at some of the preparation tables of other pupils confirmed this with incorrect forms such as duxibat and deleobat in Esme's table. Therefore, the design of the booklet for the second and third lessons was changed to incorporate more practice of the identification and creation of verb and noun forms. Overall these errors show that the pupils could recognise forms of the verbs such as the imperfect –bat ending. This is a key skill they have developed from and for reading Latin. The errors are in the formation of words but they can recognise important markers of the words they are trying to create.

The following chart shows the errors pupils made in their second story alongside the first (in brackets):

1. errors in forming 1st conjugation verbs (4 students [1]).

2. errors in forming 1st or 2nd declension nouns (4 students [2]).

3. mixing up singular and plural verbs (5 students [7]).

4. mixing up singular and plural nouns (0 students [1]).

5. adjective errors (5 students [0]).

One reason for the increase in errors is that the sheer number of forms in the preparation table seems to have overwhelmed some of the pupils. For example, Clare made one core and three non-core morphology errors and two singular and plural errors, producing Latin such as Metella ‘Caecilius! adiuvo mihi!’ clamoravit. The error with adiuvo is caused by the pupil being too self-expressive by introducing dialogue which was not the aim of the work. However, the confusion with clamoravit which is a 1st conjugation verb which the pupil would be expected to be able to put into the perfect tense suggests a continuing weakness in forming correct verb forms.

Another pupil, Adele, continued to make the error of using singular verbs with two singular subjects (e.g. Metella et Melissa ad portum curriebat). All other core learning was correct for this pupil suggesting that is was only this more advanced concept which had not been fully grasped and which had not been addressed appropriately in the teaching. Although other pupils were able to do this correctly Quintus et Metella in viam festinaverunt (Adele).

The lowest-attaining pupil in the class, Sian, who had made no errors in the first class and had used the preparation table correctly then, struggled in this case. The accusatives were consistently not made into that case but were left the same as the nominatives. Also, the preparation table did not fit with how expressive the pupil was starting to be. Similar to this Polly, while initially using the table correctly, started towards the end to slip into errors such as arbor Metella neco. Some pupils were rushing to finish their story at the end of the third lesson and this may have encouraged the pupil to rush and therefore not changing the endings but using the vocabulary as it was found.

The large rise in adjective errors, from zero to four, suggests that pupils could have used greater guidance in their use, especially with the idea of gender. Although attention was drawn to adjectives in the aid sheet (Appendix 3), guidance on how to use this effectively would have been beneficial. Pupils struggled to account for gender in their compositions, e.g., Clio, Metella motus iaceit. The adjective here has not been made to agree in gender with the noun. A more scaffolded approach to adjectives, especially as they are part of the core learning, would seem to be required.

Despite the specific errors discussed, many pupils, some without any aid from the teacher, accurately produced sentences of a complexity far beyond what was encouraged. For example, Charlie, servus pecuniam Metellae dedit. This showed a willingness on the part of even some of the weaker or less confident pupils to challenge themselves to see what they could write in Latin.

Overall, a number of the core errors can be accounted for by weakness in the teaching. Suggestions for further changes to the project which might mitigate them are discussed in the conclusion.

RQ1. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition lead to an elevated level of engagement in the process of learning to compose in Latin?

The lesson sequence was made up of a range of different activities. It is difficult to judge from pupils’ evaluation of the lesson sequence, or even of a single lesson, which part or parts they enjoyed or did not. For example, while we will see below that pupils did generally respond positively to the lessons, there was an overwhelmingly negative response to the initial measure of their base ability at prose composition. The observing teacher wrote that ‘Initially students are not trying the tasks and some very high achievers (Clio, Ellie, Adele) are simply loudly repeating that they cannot do it (defence mechanism, risk averse students).’ The class was observed by the teacher to respond negatively to the exercise and it produced a cautiousness in the pupils which took a large amount of the first lesson to overcome. The pupils became risk-averse, quiet and reserved until they had picked up the process of translation which the booklet was encouraging them to follow. However, by the end of the lesson all but one pupil ranked the lesson 6 - 9 out of 10 for enjoyment.

May, who responded very positively in the questionnaires about the lesson (9/10) at the end of Questionnaire 2 also wrote that the lesson ‘was better than any other English to Latin lessons’. This pupil also expressed a strong enjoyment of writing stories in English (10/10). She produced a story which was notably expressive, using three adjectives correctly, although they stretched the limits of their ability to be accurately expressive writing nemo Metellam miser for ‘nobody was sad about Metella’. Furthermore, when the opportunity was offered at the end of the third lesson for pupils to read out their story to the class May was observed as taking pride in sharing her work with her classmates. The other pupil to give a 9/10 score for their enjoyment of the first activity also took pride in reading out her final mors Metellae story for the class. There are, therefore, multiple pieces of evidence to suggest that these two pupils really enjoyed the lessons and engaged well it the content. If we then look at their performance in terms of accuracy of their translations, we see that May made two core errors in tremores and no core errors in mors Metellae, while Esme made no core errors in either activity. This is a higher level of accuracy than many of the other pupils. Given especially that Esme was a one of the weaker pupils in the class it was encouraging to see her both enjoying the lesson and performing well. Two other pupils felt confident enough to share their stories as well. Pupils were curious about what their classmates had written and some swapped booklets to read each other's. Some pupils were observed by the teacher encouraging their classmates to share their story after they had read it. This created a positive atmosphere of mutual appreciation of each other's work. However, as this was observed by the class teacher it is likely that only the behaviour of pupil engaged in sharing their stories was accurately perceived and recorded. Nine pupils did not share their story with the whole class. Partly this was an issue of time but also issues about not being comfortable sharing creative produce must be considered.

One pupil responded negatively to the survey of their enjoyment, Clio, who gave both enjoyment of story writing in English and the lesson a score of 3/10. No notes were made of her engagement in the lesson. It is possible that she represents pupils who are uncomfortable with being creative and sharing that self-expression but the lack of data makes it impossible to form any meaningful conclusions.

The rest of the scores, in the 6-7 range for the first lesson, indicate a generally positive experience by the pupils of the class. In all 12 out of 13 (92 per cent) gave the class a 6 /10 or more for enjoyment. However, given that this is a subject that they have all opted to take it is difficult to draw any firm conclusion as to whether it was this class particularly that they enjoyed or that expresses their underlying enjoyment of a subject they have opted for. Therefore, only the outlying results have been discussed in detail as representing strong opinions about the lesson. There is also the issue with using a numerical scale for pupils to represent something so subjective. It is hard to say whether one pupil's score of 7 is the same as another's 9 or 5. Fody (Reference Fody2009) that ‘when respondents are asked to indicate whether they ‘strongly agree’ – ‘strongly disagree’, etc., with the item, the researcher can neither be sure that the same answers from different respondents have the same weights nor that similar answers to different items given by the same respondent carry equal weights’ (Fody, Reference Fody2009, p. 162). It is hard therefore to draw any more exact conclusions from this data than that overall the pupils reported that they enjoyed the lesson.

The pupils’ responses to the end of project questionnaire do, however, add to the evidence that the pupils enjoyed the lessons. One pupil highlighted the novelty of the experience:

I liked doing these lessons, it was a change from what we normally do which was interesting. (Lily)

This raises the possibility that it was not the nature of the activity itself but the fact that it was the novelty which made it enjoyable for the pupils. Other pupils, however, did pick out the story writing element as being a source of enjoyment:

I liked doing the story writing, it was interesting. (Adele)

They also felt that the act of writing in Latin had been made easier for them but they had still found it challenging:

It has been made very simple and enjoyable yet challenging so I feel they have been beneficial. (Sian)

All pupils interviewed also felt that the project had deepened their understanding of Latin:

I have a stronger understanding of word order. (Sian)

I have learned how to translate Latin more accurately. (Clio)

To translate better and how to form sentences. (Tabitha)

I have learnt how simple it can be to translate English into Latin and I have a stronger understanding of word order. (Adele)

I also feel more confident with word order in a Latin sentence because of the grid format. (Nancy)

Overall, this agrees with the evidence from the survey that the pupils generally enjoyed the lessons. However, as this was a small self-selecting group who were willing to give up five minutes of their lunchtime to complete the questionnaire it is probable that the students who would undertake this would be one who did have a positive experience. Therefore, the data cannot be seen as representative of the whole class.

Observation notes, both by the class teacher and an observing teacher, support the rest of the data in suggesting that pupils enjoyed and engaged with the material in a productive way. The observing teacher noted that as the pupils were leaving the first lesson one pupil said, ‘that went quickly’. The pupil's tone was that it had been an enjoyable experience that they had got caught up in doing. This was a one-off comment that shows that the pupil felt there was something different about the lesson that had made it seem to pass quickly. By the end of the first lesson the observing teacher noted that ‘there is lots of good, positive work attitude developing towards composition by the end of the lesson and all students are trying hard’. After a difficult start to the lesson, which was caused by the inappropriate material used, and some difficulties with the teaching mid lesson the pupils did seem to engage positively with the core activity by the end of the lesson. As has been mentioned, the teaching and activities for the second and third lesson were altered to provide better structure and foundations for the ‘writing to learn’ stage.

In the subsequent lessons the observing teacher noted that the change in the planning to practise forming endings using iPad activities was good with ‘self-marking exercises to help all students to succeed’. The activity which pupils kept a tally of on the front of their books using only puella, servus and expectat was noted as being a ‘very good concept and allows students to focus on manipulation rather than vocabulary recall’. On the whole in the second and third lessons it was noted that ‘students work well and with minimal questions. They are confident and able to work independently.’ By the end of the three lessons pupils could write stories in Latin with a high level of accuracy and were proud enough of their achievements to share them with the class.

Conclusion

By the end of three lessons pupils could write stories of approximately 30 words making, on average, one core and two non-core errors, making 90 per cent of the Latin they were producing correct. Weaknesses in the teaching contributed to these. Pupils were engaged throughout the lessons and took pride in their work and shared it with their classmates.

However, the nature of the data collected leaves a lot of questions unresolved. Pupils who reported a predilection for creative writing enjoyed creative writing in another language and pupils who reported an ill disposition towards it likewise enjoyed the lesson less. However, based on three main data points (May, Esme and Clio), it is impossible to draw any firm conclusions about this.

To return to the research questions:

RQ1. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition lead to a greater level of engagement in the process of learning to compose in Latin? The data point towards pupils enjoying the lessons and working diligently. However, the circumstances of the study must limit the meaning of this. Pupils may have been responding to the novelty of the exercise. Repeating the exercise with the same group a number of times at intervals might reveal whether this novelty factor is an issue. Also, the issue of pupils being uncomfortable with expressing their creativity was not picked up by the data that was collected and so cannot be analysed.

RQ2. Does the use of ‘free composition’ as a means of teaching Latin prose composition produce a high level of accuracy in pupils’ work? With the scaffolded approach used in this study some pupils could produce a very high level of accuracy. Some pupils did make errors when their attempts to express something slightly beyond their grasp failed them but such subtleties take time to acquire. Better organisation of the teaching and more scaffolded extensions, for grammar such as adjectives, would also help to maintain a high level of accuracy as pupils stretched themselves.

In a climate where prose composition has returned to the examination at GCSE and continues at A Level, teachers need to find ways of teaching it that promotes pupils’ enjoyment of the subject and encourages them to write accurate Latin. This study could have looked at the impact of the teaching on pupils’ ability to translate the exam-style questions which pupils will meet at GCSE. However, many of the marks on the examination are for being able to recall vocabulary and this project was focused to a much greater extent on making pupils familiar and comfortable using grammar. Other studies have shown the value of giving pupils creativity in prose composition to increase engagement at the same time as developing language skills. It is hoped that this study has gone a small way towards supporting that hypothesis while also raising some important questions about pupil discomfort with creative responses.

Appendix 1: tremores workbook

Storytelling Project

Brief introduction: One of the options on your GCSE Latin language paper will be to write three sentences in Latin. This project is designed to allow you to practise writing Latin sentences and to allow you to retell the story of what happened in Pompeii when Vesuvius erupted and to tell some of the story left untold in the Cambridge Latin Course.

Questionnaire

Circle the appropriate score for each question:

1) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how much do you like writing stories in English? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how much do you like reading the stories in the Cambridge Latin Course? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

3) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how confident do you feel translating from Latin into English? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

4) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how confident do you feel translating from English into Latin? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Exercise I.

Translate these sentences into Latin:

1) The slave girls are walking.

2) The masters entered the long forum.

3) The terrified crowd was waiting for the god.

Give yourself a mark out of ten based on how well you think you have done: /10

Exercise II – Reading

1) Read the story tremores from book 1, stage 12, lines 1-19.

Exercise III - Preparation

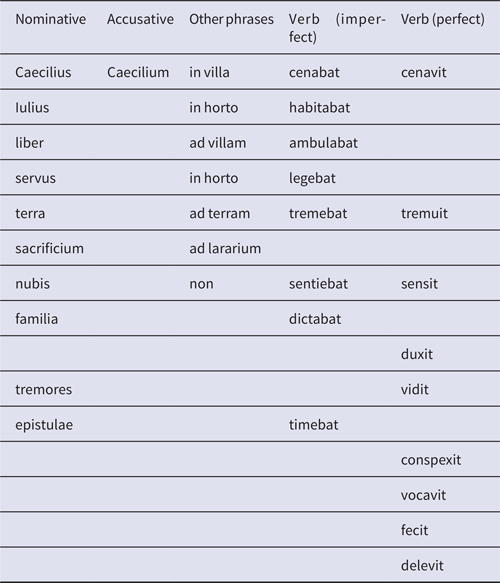

1) Complete the table below:

Exercise IV – First draft

Rewrite the story tremores in Latin using the table above. You must include at least a Nominative and one verb. You may include an accusative or one of the ‘other phrases’.

Exercise V – First Review

Write your sentences out into a continuous passage. Then give it to another member of the class to translate into English.

Exercise VI – Draft II – Adjectives, Adverbs and link words

Add to the table below from the story tremores or from the word list at the back of the booklet.

Exercise VII – Second draft

Write your sentences again, this time including at least one adjective, adverb or a link word in each sentence. Then give it to a different other member of the class to translate into English.

Make an illustration of your story:

Questionnaire II

Circle the appropriate score for each question:

1) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how much have you enjoyed this activity? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2) On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘very much’) how hard have you found this activity? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Do you have any other comments?

English to Latin Vocabulary

Appendix 2: mors Metellae by Esme

Metella pecuniam Caeilii clam portavit. Quae ad urbem fugiebat. Grumio Metellam conspexit. Grumio post Metellam venit. Metella sollicita erat. Grumio Metellam oppugnavit. Grumio iratus Metellam necavit quod Metella erat fugiebat cum pecuniam Caecilii.