There is evidence that patients who are admitted to hospital at the weekend are at increased risk of dying compared with patients admitted at other times, Reference Bray, Cloud, James, Hemingway, Paley and Stewart1–Reference Ruiz, Bottle and Aylin5 but the reasons for this are unclear. Reference Lilford and Chen6 In England it has been suggested that the ‘weekend effect’ could account for 6000 excess deaths per year. Reference McKee7 One explanation relates to reduced hospital staffing on Saturday and Sunday, and it has been argued that some deaths could be prevented if patients had continual access to high-quality care. A ‘7-day National Health Service’ (NHS) is currently a policy priority in the UK. Reference England8 However, it is likely that the potential for prevention varies from speciality to speciality and between settings. Reference Lilford and Chen6 Previous studies have examined mortality following any admission, Reference Freemantle, Ray, McNulty, Rosser, Bennett and Keogh3 emergency and elective surgical admission Reference Ruiz, Bottle and Aylin5 and after stroke, Reference Bray, Cloud, James, Hemingway, Paley and Stewart1 but the weekend effect is a relatively unexplored phenomenon in mental health. A study carried out in a single London hospital suggested no increase in all-cause mortality for patients admitted to a psychiatric bed at the weekend. Reference Patel, Chesney, Cullen, Tulloch, Broadbent and Stewart2 Suicide is a key outcome for mental health services, Reference Harris and Barraclough9 and has previously been used as a marker of the quality and safety of care. Reference While, Bickley, Roscoe, Windfuhr, Rahman and Shaw10 Some groups of patients, such as current or recent in-patients, Reference Kapur, Hunt, Windfuhr, Rodway, Webb and Rahman11,Reference Qin and Nordentoft12 or those receiving intensive treatment at home as an alternative to admission, Reference Hunt, Rahman, While, Windfuhr, Shaw and Appleby13 are at particularly high risk of dying by suicide.

In this study we investigated the timing of suicide in a national patient sample. Temporal variations in suicide by season of the year or day of the week have been investigated in a number of studies previously. Reference Plöderl, Fartacek, Kunrath, Pichler, Fartacek and Datz14–Reference Simkin, Hawton, Yip and Yam16 However, our aim in this study was not to describe the timing of suicide in the general population, but to examine the specific weekend v. weekday incidence of suicide in very high-risk patient groups who might be most vulnerable to changes in service provision. We hypothesised that a weekend effect would manifest itself as an increased incidence of suicide on Saturday and Sunday compared with other days of the week. Another point in the calendar where there may be significant staffing disruption is the changeover point for junior doctors, Reference Young, Ranji, Wachter, Lee, Niehaus and Auerbach17 particularly in August in the UK when many start work for the first time. We hypothesised that an August effect might result in a higher incidence of patient suicide in that month compared with others.

Method

Data acquisition

Suicide data were collected as part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). Reference Appleby, Shaw and Amos18 Data collection has been described in detail elsewhere. Reference Windfuhr, While, Hunt, Turnbull, Lowe and Burns19 Briefly, it occurred in three stages. First, national data on people who had died by suicide in the general population in England were obtained from the Office of National Statistics. Second, NHS mental health services identified which of these individuals had been in contact with services in the 12 months before death. These trusts also identified the clinician who had been caring for the patient prior to their suicide. Third, detailed questionnaires were sent to the clinicians to obtain demographic and clinical data (including care at the time of death). Case ascertainment is relatively complete with a response rate for questionnaires of over 95%. Reference Windfuhr, While, Hunt, Turnbull, Lowe and Burns19

Deaths that received either a suicide or open verdict at coroner's inquest were considered to be suicide deaths in the current study, as is the convention in suicide research in the UK. Not including open verdict deaths has been shown to underestimate the number of suicides by up to 50%. Reference Linsley, Schapira and Kelly20,Reference Gunnell, Bennewith, Simkin, Cooper, Klineberg and Rodway21 Both the cases that received a suicide verdict and those that received an open verdict are collectively referred to as ‘suicides’ in the rest of this paper.

Study sample

The present study included individuals aged 10 years and over who died by suicide between 2001 and 2013 in England. The National Confidential Inquiry does not collect data on young children, where intentions and motivations may be difficult to establish. Reference Windfuhr, While, Hunt, Turnbull, Lowe and Burns19 Previous studies of acute hospital mortality have used data collected over a single financial year, Reference Freemantle, Ray, McNulty, Rosser, Bennett and Keogh3 but because of the comparative rarity of suicide as an outcome we used data collected over a longer period. Some groups of patients with mental health disorders are at particularly high risk of suicide. They include psychiatric in-patients and those recently discharged from in-patient care, Reference Kapur, Hunt, Windfuhr, Rodway, Webb and Rahman11,Reference Qin and Nordentoft12 and those under the care of crisis resolution home treatment (CRHT) teams (a service intended as an alternative to admission). Reference Hunt, Rahman, While, Windfuhr, Shaw and Appleby13 These groups are in close proximity to care and may be more affected by weekend changes to staffing or service availability than other patients. We therefore chose to focus on them in the current study.

Main outcome

Our main outcome was risk of suicide in relation to day of death. Previous investigations of the weekend effect in hospital settings have examined the risk of death by day of admission. Reference Freemantle, Ray, McNulty, Rosser, Bennett and Keogh3 Suicide commonly occurs in the context of complex difficulties, but the final act may be relatively impulsive and in response to an acute stressor. Reference Turecki and Brent22 Care at the time of death may therefore be a more important determinant of outcome than care at the time of admission. In addition, lengths of stay for in-patient mental health services are much longer than for acute medical or surgical specialities, 23 and so care immediately following admission may be less critical in terms of mortality risk.

Statistical analysis

We initially examined the timing of suicide by day of the week. We expressed the incidence of suicide as the number of suicide deaths per 100 days at risk (for example, the number of suicide deaths on a Monday per 100 Mondays at risk throughout the study period or the number of suicide deaths in January per 100 January days at risk). Suicide deaths are statistically rare events that can generally be expected to follow a Poisson distribution. Consequently, Poisson regression models were fitted with the number of suicides on each day as the dependent variable. Models were tested for overdispersion (where variation is high and violates the use of a Poisson model), and if this was evident, negative binomial regression models were fitted to account for high variation. The use of these models allowed the calculation of incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals, comparing the suicide incidence at the weekend with the suicide incidence during the working week. P-values less than 5% were considered significant. Levels of missing data were low – only two patients in the whole sample did not have details of the care they had been receiving at the time of death.

Although our main focus was on risk of suicide in relation to day of the week, we did also examine the risk of suicide by day of admission for the in-patient sample only. In order to investigate a possible August effect we examined the timing of suicide by month of the year. The ‘August effect’ (or its USA counterpart, the ‘July effect’) refers to the possible reduction in the quality and safety of care when final-year medical students become doctors and junior doctors become a grade more senior. Reference Young, Ranji, Wachter, Lee, Niehaus and Auerbach17,Reference Blakey, Fearn and Shaw24 There are other potential transition points, but the summer one is the best described and some of the other changeovers in the UK (for example every 4 months) are comparatively recent developments (post 2005).

Results

Over the study period there were 1621 in-patient suicide deaths, 2819 suicide deaths within 3 months of in-patient discharge and 1765 deaths under CRHT teams. Although in-patients were a distinct group, 592 (21%) of the post-discharge deaths were also under CRHT. Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients who died by suicide between 2001 and 2013 in the study

| Characteristics | In-patients (n = 1621) |

Within 3 months of discharge (n = 2819) |

Under care of CRHT team (n = 1765) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 44 (15–96) | 45 (15–95) | 48 (15–95) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1031 (64) | 1800 (64) | 1082 (61) |

| Female | 590 (36) | 1019 (36) | 683 (39) |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Schizophrenia and other delusional disorders | 483 (30) | 455 (16) | 229 (13) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 190 (12) | 300 (11) | 161 (9) |

| Depressive illness | 602 (37) | 990 (35) | 845 (48) |

| Other diagnosis | 346 (21) | 1074 (38) | 530 (30) |

| Method, n (%) | |||

| Hanging/strangulation | 728 (45) | 1175 (42) | 813 (46) |

| Self-poisoning | 143 (9) | 644 (23) | 357 (20) |

| Other methods | 750 (46) | 1000 (35) | 595 (34) |

| History of self-harm, n (%) | 1227 (76) | 2124 (75) | 1223 (69) |

| History of drug and/or alcohol misuse, n (%) | 759 (47) | 1492 (53) | 743 (42) |

CRHT, crisis resolution home treatment.

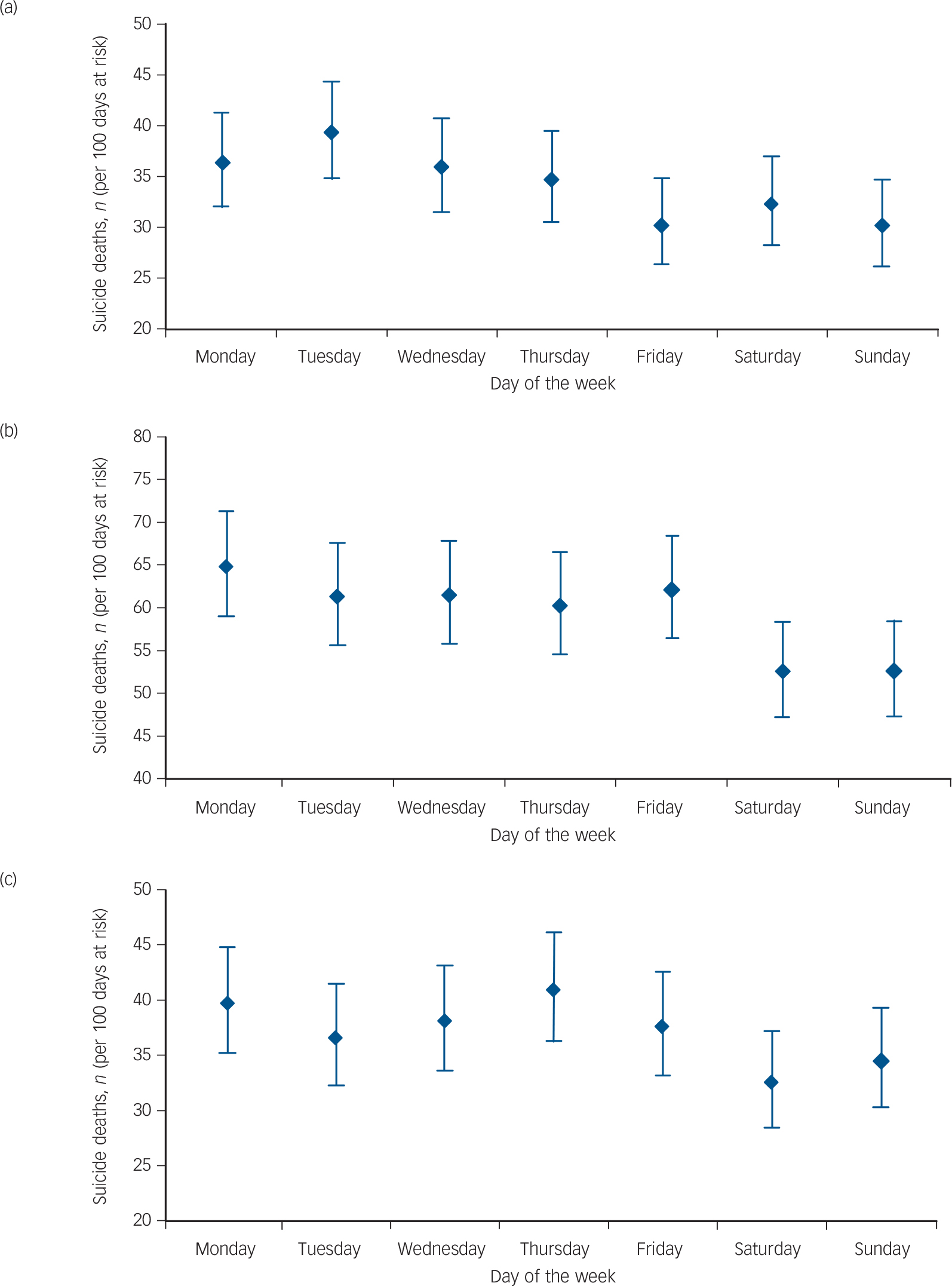

Figure 1 shows the timing of suicide in relation to day of the week. There was a significant difference in the incidence of suicide between weekdays and weekends for all patient groups, with a lower suicide risk at weekends (in-patients: IRR = 0.88 (95% CI 0.79–0.99); post-discharge patients: IRR = 0.85 (95% CI 0.78–0.92); patients under CRHT: IRR = 0.87 (95% CI 0.78–0.97)).

Fig. 1 Patient suicide in England by day of the week (2001–2013).

(a) In-patients: weekend v. weekday incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.88, 95% CI 0.79–0.99, P = 0.03. (b) Post-discharge patients (suicide within 3 months of in-patient discharge): weekend v. weekday IRR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.78–0.92, P<0.001. (c) Patients under crisis resolution home treatment (CRHT): weekend v. weekday IRR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.97, P = 0.01.

Figure 2 shows the timing of suicide in relation to month of the year. There was no evidence of an August peak in suicide. The peak month for incidence of suicide was May for in-patients, September for post-discharge patients and November for CRHT team patients.

Fig. 2 Patient suicide in England by month of year (2001–2013).

(a) In-patients: August v. other months incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.99, 95% CI 0.83–1.18, P = 0.93. (b) Post-discharge patients (suicide within 3 months of in-patient discharge): August v. other months IRR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.88–1.15, P = 0.90. (c) Patients under crisis resolution home treatment (CRHT): August v. other months IRR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.96–1.37, P = 0.14.

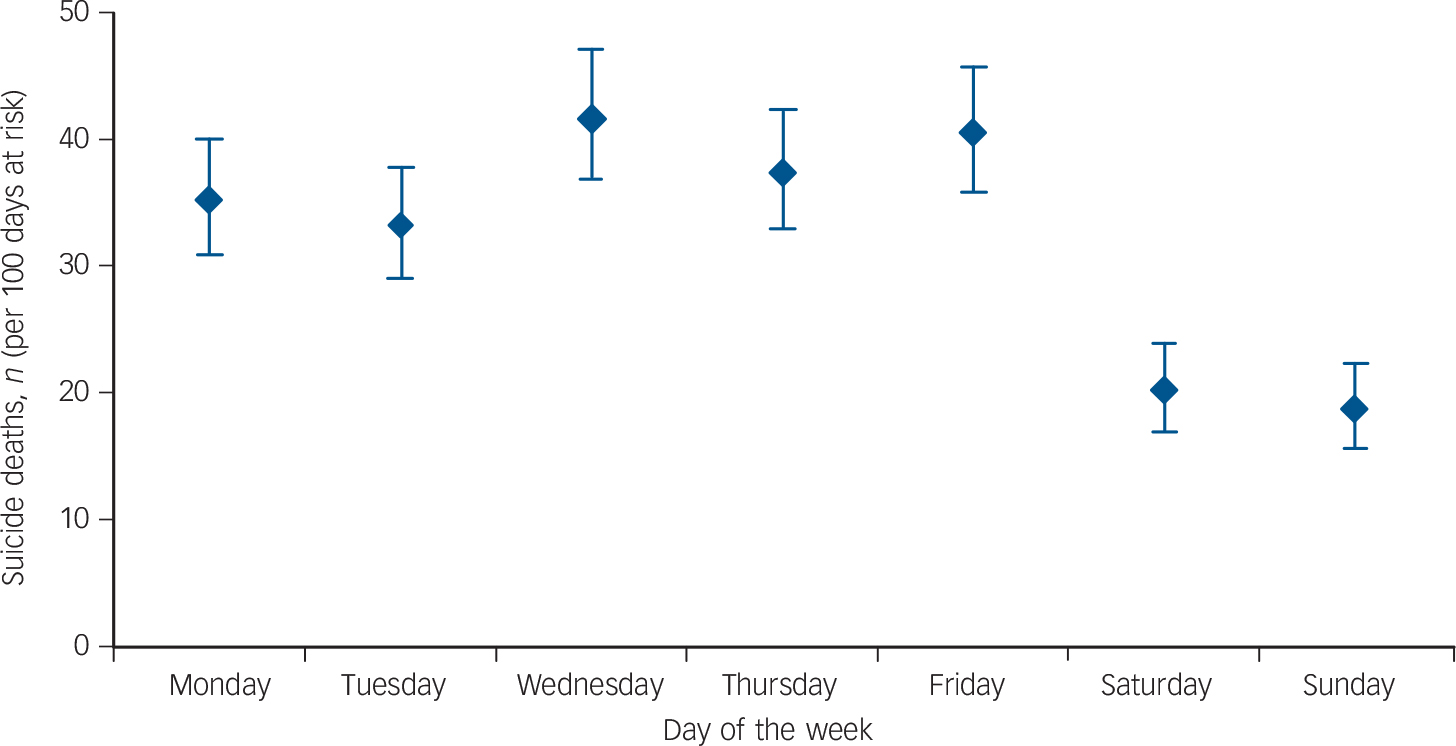

Figure 3 shows the timing of suicide in psychiatric in-patients in relation to day of admission. Patients who died by suicide were less likely to have been admitted to hospital on a Saturday or Sunday than during the week (IRR = 0.52 (95% CI 0.45–0.60), P<0.001). We obtained similar findings when we restricted the analysis to people who had died within 30 days of admission: IRR weekend v. weekdays = 0.65 (95% CI 0.54–0.78), P<0.001; or people who had died within 7 days of admission: IRR weekend v. weekdays = 0.70 (95% CI 0.53–0.94), P = 0.02.

Fig. 3 Suicide in England by day of admission (in-patients 2001–2013).

Weekend v. weekday incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.52, 95% CI 0.45–0.60, P<0.001.

Discussion

Main findings

We found clear evidence of a weekend effect for suicide deaths among mental health patient groups, but contrary to our hypothesis, the incidence of suicide was actually 12–15% lower at the weekend. Similarly, when we re-ran our analysis for in-patients only based on the day of admission, the incidence of suicide for patients admitted on a Saturday or Sunday was much lower than for those admitted during the week. We found no evidence for an August peak in suicide related to the changeover of junior doctors.

Strengths and limitations

Our study involved national data collection with excellent coverage, but our findings need to be interpreted in the context of a number of methodological limitations, the most important of which is the purely descriptive design. We were, of course, unable to investigate causal mechanisms using this approach. We did not adjust for potential case mix differences as our analyses were based on people who had died by suicide rather than an at-risk cohort. It is therefore possible, although we think unlikely, that our findings are the result of patients under mental healthcare at the weekend being at lower risk than patients during the working week. The reduced IRRs could reflect fewer people under mental healthcare at the weekend, but in-patients on weekend leave would be captured in our figures (and in fact the proportion of in-patients who died while on agreed leave at weekends and during the week was similar (56% v. 52%, χ2 = 1.69, P = 0.19)). Of course if many more patients were formally discharged from in-patient wards on a Friday this might partly account for the findings, but this would not apply to post-discharge or community patients or our analysis based on day of admission.

Another potential weakness is that we considered the day of death as our main outcome rather than the day of the actual episode of suicidal behaviour. Self-poisoning is one method of suicide for which there may be a lag between the suicide episode and death. However, when we ran additional analyses, we found no significant difference in the temporal pattern of suicide by different methods (interaction terms for self-poisoning v. other methods were non-significant). It is also possible that some deaths were not discovered until after the weekend and so an inaccurate date of death was recorded on the death certificate. However, this is unlikely to apply to the in-patients and patients under the care of home treatment teams (who should have been seen by staff on a frequent basis) or to post-discharge patients who lived with others (around half the post-discharge sample).

Interpretation of findings

How might we explain our findings? If reduced medical staffing does indeed account for the weekend effect in acute medical and surgical specialities, Reference Ruiz, Bottle and Aylin5,Reference Lilford and Chen6 it may be that mental health is relatively protected from this because it is more community focused, more multidisciplinary in nature and perhaps less reliant on on-call medical staff out of hours. It could also be that increased social contact with families and others at weekends helps prevent some suicide deaths at this time. Reference Bradvik and Berglund25 It is also worth noting that some previous studies that reported an elevated mortality related to weekend hospital admission actually found a slightly reduced weekend mortality among people who remained in-patients that is consistent with our study. Reference Freemantle, Richardson, Wood, Ray, Khosla and Shahian26

The much lower incidence of suicide in people admitted at the weekend in our study is interesting. It could relate to a possible reduced threshold for admission in the absence of high-quality weekend cover in community services, which results in ‘lower-risk’ patients being admitted. A recent paper that suggests shorter admissions for patients admitted to a psychiatric bed at the weekend is consistent with this. Reference Patel, Chesney, Cullen, Tulloch, Broadbent and Stewart2

Suicide is a complex phenomenon with a variety of causes, and another explanation for our findings could be that wider societal and environmental factors are more important determinants of suicide than mental health service provision. However, aspects of psychiatric services can be related to suicide, Reference While, Bickley, Roscoe, Windfuhr, Rahman and Shaw10 and we have previously shown an association between staffing turnover and suicide rates in UK mental health services. Reference Kapur, Ibrahim, While, Baird, Rodway and Hunt27 The patients included in this study had high levels of morbidity and need – the majority had significant psychiatric illness and a history of previous suicidal behaviour, and almost half had a history of alcohol or drug misuse. They died in close proximity to care, and we focused on them in the current study because they might be expected to be the groups most vulnerable to changes in care and supervision. We think it is unlikely that the drivers of temporal variation in suicide in these complex clinical groups are identical to the drivers in the general population. Nonetheless, it is possible that any service-related changes in this study were masked by the more general temporal variations in suicide. Previous general population and clinical studies have also found peaks in suicide at the beginning of the working week and in spring. Reference Cavanagh, Ibrahim, Roscoe, Bickley, While and Windfuhr28–Reference Ajdacic-Gross, Bopp, Ring, Gutzwiller and Rossler32 However, when we ran a post hoc analysis based on all suicide deaths in the general population in England (2001–2013) we found that the weekend v. weekday difference was actually slightly smaller than the one we found in the clinical groups – incidence of suicide around 8% lower at the weekend in the general population v. 12–15% lower at the weekend in the patient groups (although these differences were not statistically significant when examined using tests of interaction, P-values ranging from 0.18 to 0.56).

Seven-day working for medical staff is currently a policy priority in the NHS and has a number of potential advantages, such as improving access to care, enhancing continuity of support and reducing morbidity. A key aim of such models is to improve quality and save lives. However, our study does not support the claim that safety is compromised at weekends, at least in mental health services.

Funding

The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) commissions the Mental Health Clinical Outcome Review Programme, NCISH, on behalf of NHS England, NHS Wales, the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorate, the Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), and the States of Jersey and Guernsey. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not the funding body. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH); our thanks to the other members of the research team: Sandra Flynn, Cathryn Rodway, Alison Baird, Su-Gwan Tham, Myrsini Gianatsi, Rebecca Lowe, James Burns, Philip Stones, Julie Hall, Nicola Worthington and Huma Daud.

We acknowledge the help of district directors of public health, health authority and mental health service contacts, and all respondents for completing the suicide questionnaires.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.