A growing literature on authoritarian resilience and resurgence emphasizes the importance of strong economic performance in generating popular support for autocrats.Footnote 1 But what precisely constitutes strong economic performance in the minds of citizens living in autocracies? And how do processes of social and economic transformations shape judgements of the state's economic performances? Past research from China and the post-Soviet world suggests that relying on economic growth and expanding household incomes alone is not a viable legitimation strategy for the long run.Footnote 2 This is partly because citizens’ implicit benchmarks for evaluating autocrats’ economic performance are themselves in flux; public opinion of economic affairs is shaped by belief systems that shift with underlying changes in material circumstances. Processes of ideological and value pluralization that attend economic development can often lead to the emergence of new expectations of the state in its economic functions.Footnote 3 In particular, growing affluence may generate increased demand for relatively meritocratic and impartial “inclusive” economic institutions and a rejection of “extractive” institutions that channel particularistic benefits to regime insiders and supporters.Footnote 4

Our article contributes to the study of authoritarian legitimation in China by examining citizens’ views of two critical economic roles of the state beyond growth-promotion – state ownership and market regulation – that shape citizens’ overall impressions of the state's economic performance. While scholars have previously analysed public perceptions of the state's economic performances that are most directly tied to individual material well-being, for example growth and redistribution including public goods provision, public attitudes towards these other functions of the Chinese state have yet to be carefully studied. Since both the propriety of state ownership and suitable models of market regulation have stirred passionate debate among policy elites in China, we focus on these policy domains and examine the extent to which expert critiques of the so-called “China model” resonate in wider society.Footnote 5

Based on an original survey conducted in 2015–2016 in six Chinese cities, we find that Chinese citizens have a sophisticated and, on some issues, quite critical view of the state's economic performances in the domains of regulation and ownership. Our results show, first, that there is a high degree of implicit agreement within China about what economic roles the government ought to perform. Most respondents express support for an interventionist state that takes an active role in shaping market outcomes; however, there is a concurrent desire for these interventions to be inclusive, such that market players close to the state, especially state-owned enterprises (SOEs), do not benefit improperly. Further, respondents’ evaluations of actual economic performances suggest that the state is not always meeting expectations and this is particularly apparent in public opinion regarding competition policy and pollution control. Finally, statistical analysis shows that young people are, on the whole, both more doubtful about the state's highly interventionist stance in the economy and more likely to see it carrying out its duties poorly. This last finding raises questions about the efficacy of the state's legitimation efforts vis-à-vis urban youth in the coming years.

Economic Legitimation and Authoritarian Resilience

An overriding point to emerge from the recent surge in research on authoritarian systems is that autocracies are held together by much more than coercion and repression. Autocrats employ sophisticated means of managing competitive tensions between political elites, and they strive to secure regime stability by generating a degree of popular support for themselves.Footnote 6 The use of economic growth promotion and redistribution to produce “popular” autocracies is especially common.Footnote 7 Indeed, research on legitimation strategies employed by post-Soviet non-democracies finds that among a wide range of legitimating claims including reference to foundational myths, ideology, personalism, international engagement, rule-based procedures and economic performance, rulers are most likely to present themselves as “guardians of citizens’ socio-economic well-being.”Footnote 8

The People's Republic of China is arguably the world's best example of such economically “populist authoritarianism.”Footnote 9 While some might assume that the increasingly harsh repression of a widening circle of perceived opponents of the state – including artists, lawyers, dissidents, activists, journalists, liberal university professors and ethnic minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang – would weaken public support for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) within China, most available evidence does not support this view. The World Values surveys have consistently shown that Chinese citizens have among the highest rates of confidence in their government in the world.Footnote 10 The most recent data find that fully 85 per cent of Chinese respondents report a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in government, and this finding of broad public support is supported by a variety of survey-based academic research.Footnote 11 It bears noting, however, that preference falsification likely inflates these figures to some degree.Footnote 12

One commonly finds the claim, in both scholarly and popular discussion, that public backing for China's one-party rule is based, first and foremost, on the state's ability to deliver the goods in economic terms.Footnote 13 Yet, economic growth is an inherently shaky foundation of authoritarian stability. First, the occurrence of economic crisis can be extremely destabilizing if it serves to alter citizens’ perceptions of the costs and benefits of authoritarian rule leading to popular uprising and/or engendering divisions within the ruling elite.Footnote 14 In China's market reform period, effective macroeconomic management has kept the nation from falling into deep economic crisis at several critical junctures; however, it has now entered a period of secular slower growth and is struggling to steer around the middle-income trap. An open question regarding this “new normal” (xin changtai 新常态) is whether a prolonged economic slow-down in China, even if it follows a slow and gradual curve, could ultimately threaten the CCP's authoritarian survival.

Further, quite apart from the vagaries of markets, autocrats who base their authoritarian legitimation strategies on economic growth may ultimately wind up as victims of their own success. Processes of social transformation that attend rapid economic development typically lead to shifts in public expectations of the state in the marketplace. Whereas citizens of pre-industrial and industrializing societies tend to be supportive of a highly interventionist role for the state in the economy in line with “survival values” that emphasize deference to state authority, individuals in post-industrial societies are typically more circumspect about state interventions in the economy, in keeping with dominant “self-expression values” emphasizing personal freedom as well as fairness and tolerance in society.Footnote 15 Thus, while robust economic growth may have been a strong anchor of authoritarian legitimation in the early stages of China's reform-era economic development, citizens now accustomed to a higher base of economic well-being feasibly hold more complex expectations of the state. Further, demand for inclusive institutions may conflict with authoritarian survival imperatives since autocrats use economic levers to reward regime loyalists.

Contours of Economic Legitimation in China's New Era

Judging by debate within Chinese policy circles regarding which economic roles the state should rightfully assume and which activities should instead be left to autonomous market forces, evaluations of the Chinese state's economic performance are increasingly in the eye of the beholder.Footnote 16 In the early days of market reform, a powerful growth consensus meant that economic success was nearly synonymous with GDP growth. Today, China's leaders face a much longer and more challenging list of policy priorities, some of which stand in tension with one another. In addition to maintaining economic growth and steering around the middle-income trap, policymakers simultaneously aim to reverse a grave environmental crisis (without depressing growth), push China up the value chain, carefully liberalize the capital account, draw down local government debt, reign in industrial overcapacity, and increase social security and healthcare outlays, among other urgent policy challenges. In these vastly more complex circumstances, what are the state's economic performances that count in the eyes of Chinese citizens?

The impression that growth is no longer sufficient to generate a high degree of public consent for one-party rule is supported by Bruce Gilley and Heike Holbig's research on Chinese scholars’ discussions of legitimacy. Their analysis of academic articles on the topic of state legitimacy in China from 2002 to 2007 found that “half of all authors mentioned economic growth as a crucial component of a legitimation strategy, while over one third stressed the importance of social equality.”Footnote 17 Zeng Jinghan's follow-up study examining the discourse from 2008 to 2012 found that just 21 per cent of scholars saw economic growth as the key to the state preserving the right to rule.Footnote 18 Scholars “continuously warned about the fleeting nature of performance legitimacy and the necessity of establishing more solid legitimacy foundations, especially rational-legal legitimacy.” Zeng concludes that “it is a near consensus that the state should find sources of legitimacy other than economic performance.”Footnote 19 Furthermore, Chinese scholars deemed “changing values” along with “socio-economic inequality” to be the major threats to legitimacy, each of which was cited in almost half of the articles.Footnote 20

If growth is no longer enough to persuade citizens of the CCP's right to rule, which economic functions of the state do citizens care about most? Previous research has also shed light on this question. Based on a nationwide survey, one study finds that citizens place relatively more weight on the state's provision of pure public goods (public security, public safety and legal order) than they do on economic growth in their evaluations of the government's trustworthiness.Footnote 21 Another study suggests that the quality of economic governance is key: citizens’ judgements about the fairness of institutional arrangements are of primary importance in shaping their overall impressions of economic performance.Footnote 22

Relatedly, recent literature identifying an ideological spectrum in China would suggest that the particular economic roles the public demands from the state vary somewhat according to individuals’ economic beliefs.Footnote 23 The ideological spectrum divides between, on one end, individuals who hold “authoritarian-traditional-nonmarket” values – i.e. those who support authoritarian rule, traditional values and a high degree of state intervention in the economy – and, on the other end, those who embrace “liberal-nontraditional-market” values and who favour political liberalization, oppose traditional socio-cultural norms and support market-oriented policies.

Driven in part by shifting values and ideologies, Chinese citizens’ perceptions of the state's economic performance appear to be becoming increasingly varied, nuanced and critical. It would seem that growth alone is no longer sufficient to secure favourable impressions of the state's economic performance. This is especially the case for those who have grown up in a relatively secure economic period. Younger generations increasingly expect the state to extend the benefits of growth to all more deftly and also improve the fairness of market outcomes. In the remainder of the paper, we substantiate this claim through analysis of Chinese citizens’ views of two critical duties of the sovereign, state ownership and market regulation.

Methodology

To study citizens’ attitudes to the state's economic performance beyond growth and redistribution, we conducted a pilot online study in the summer of 2014 and followed up with a random digit dialling telephone survey that ran from late 2015 to early 2016. We targeted urban residents (aged 21 and above) located in six cities corresponding to varying levels of socio-economic development and tiers: Beijing and Shanghai (tier-one); Chengdu, Hefei, Hohhot and Wuhan (tier-two). Our sample size was 1,025 respondents, with a sampling scale of 131,291 persons involving 68,162 telephone numbers.Footnote 24 As shown in Table 1, the demographics of our survey sample and those of urban residents from the 2010 census are fairly close.

Table 1: Sample Demographics

Notes:

* from 2015 China Statistical Yearbook.

Our survey employed a seven-point Likert scale to measure the strength of respondents’ agreement/disagreement with queries. This analysis focuses on responses to ten question blocks relating to state ownership, competition policy, industrial policy, macroeconomic management and environmental protection.

Perceptions of State Ownership

In order to provide a detailed picture of public perceptions of state ownership in China, the survey included queries on a range of issues regarding the economic performance of SOEs, as well as the institutional environment encompassing state ownership. The data reveal that Chinese citizens are somewhat favourably disposed to the idea of state ownership, with 58 per cent of respondents expressing some degree of agreement with the statement “sectors related to national security and important to the national economy and people's livelihoods must be controlled by SOEs.”

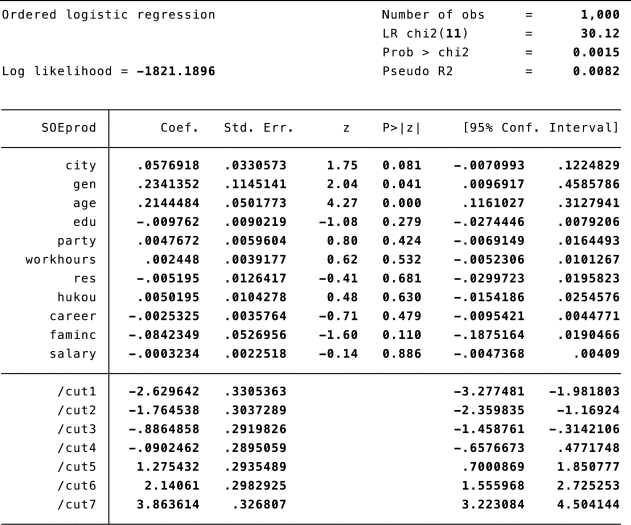

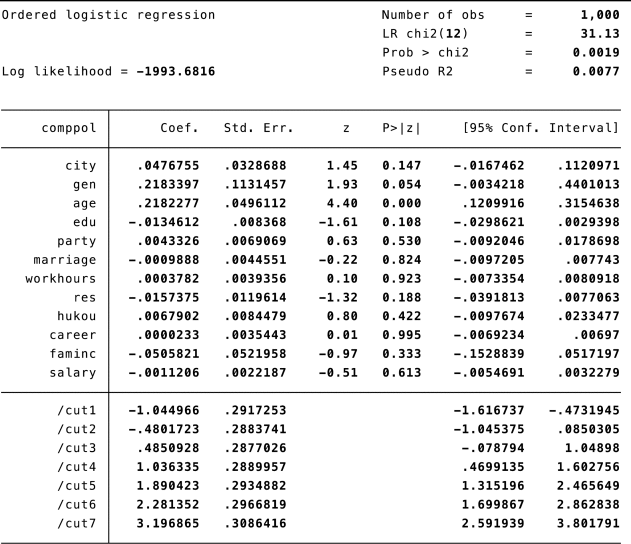

There is interesting demographic variation within the data. Statistically significant differences across age categories reveal that the youngest respondents (aged 21–30) in our sample, all of whom belong to the “one-child” generation born after 1980,Footnote 25 are significantly less likely to express firm support for state control of key sectors (see Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1).Footnote 26 Support for state ownership increases step-wise in the older age cohorts and is especially pronounced among the oldest participants (aged 51 and over), who are part of the “Cultural Revolution” generation.Footnote 27

Figure 1: Support for State Ownership by Age

While a large proportion of Chinese citizens express support for the idea of state ownership of the “commanding heights” (mingmai hangye 命脉行业) in principle, responses to other questions suggest a degree of latent dissatisfaction with the actual practice of state ownership in certain key sectors. In particular, there appears to be no strong social consensus about what sectors of the economy ought to fall under state ownership, a topic that has stirred considerable controversy in recent years.Footnote 28 Our data provide a detailed look at public opinion on state ownership of a group of SOE-dominated industries including defence, the power grid, petroleum and petrochemicals, telecommunications, coal, civil aviation and shipping.Footnote 29 Defence was the only industry for which a large majority of respondents (68 per cent) agreed that state ownership should predominate. Aggregate support for state ownership of power was 56 per cent, 53 per cent for petroleum and petrochemicals, 52 per cent for coal, 51 per cent for civil aviation and 50 per cent for shipping.

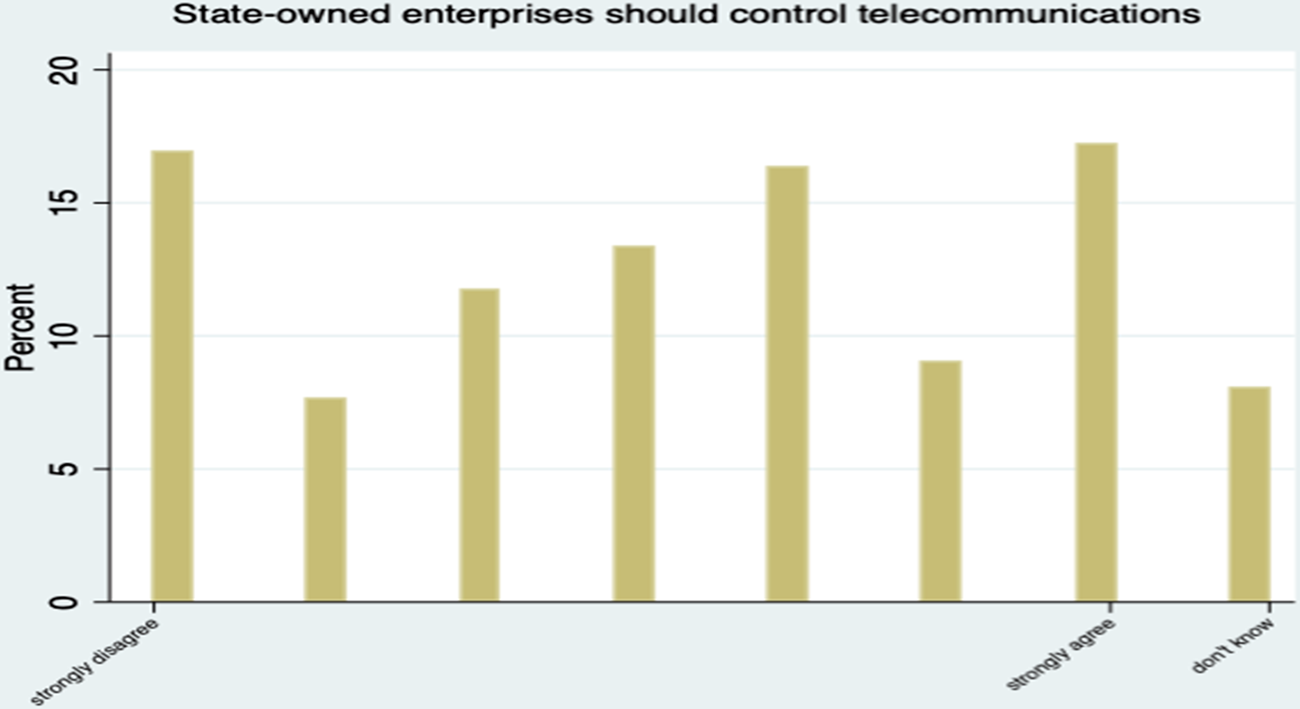

Notably, less than half of respondents agreed that state ownership should predominate in telecommunications, while 36 per cent disagreed (see Figure 2). China's telecommunications industry has been deeply embroiled in the anti-corruption campaign under the leadership of Xi Jinping 习近平 and these doubts about the state's ownership of telecommunications plausibly reflect, in part, the public impact of these scandals.Footnote 30 A higher degree of negative affect regarding state ownership of telecommunications may also reflect respondents’ misgivings about the state's monitoring and censorship of the internet and mobile communications as well as the popular view that mobile telecommunications costs are unacceptably high owing to the state's monopoly.

Figure 2: Views of Telecommunications Services

Regarding perceptions of the economic performance and competitiveness of SOEs, we find a curious discrepancy. While respondents express reservations about the capabilities of SOE managers, they convey much more faith in SOE products. Responses to the prompt “state-owned enterprises are well run” show a divided base of opinion with 38 per cent agreeing and 37 per cent disagreeing. Firms of every other ownership type rank above SOEs on this measure (Figure 3). Consistent with our other findings relating to perceptions of state ownership, younger respondents are significantly more likely to view SOE management critically (Appendix Table 2)

Figure 3: Perceptions of Enterprise Management by Ownership Type

Interestingly, the general pattern is reversed when we look at respondents’ confidence in the goods and services of firms of different ownership type (Figure 4). Almost two-thirds of respondents (66 per cent) express confidence in SOE products. There are also statistically significant differences across age categories in responses to the query about SOE products with younger respondents as well as men viewing them more critically (Appendix Table 3). How is it that large numbers of respondents perceive SOE management to be poor, but not so their products? The perception of SOEs as prone to corruption (more below) and inherently inefficient owing to the “soft budget constraint” is plausibly shaping respondents’ views on this issue.Footnote 31 Respondents may, for example, be relatively satisfied with the electricity supply they receive from the state-run power company and simultaneously regard it to be poorly run because the cost per unit produced is perceived to be too high.

Figure 4: Confidence in Enterprises’ Goods and Services by Ownership Type

While the benefits of SOE employment have been steadily rolled back in the market reform era, respondents continue to see employment in the state sector in a positive light (Figure 5). We found that 57 per cent of respondents agree that “employees are typically well-treated in SOEs” and only foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) were evaluated more highly in this category. Respondents’ positive impressions of SOE employment may reflect a shift in the preferences of university-educated job seekers towards state firms in the years following the global financial crisis and the beginnings of China's economic cooldown.Footnote 32 Analysts speculate that FIEs and private firms’ post-crisis struggles made the lure of stable employment in SOEs attractive enough to offset the perceived downsides of SOE employment: low pay and frequently unrewarding work. China's slowing economy likely adds to the appeal of SOE employment relative to employment in firms that are more vulnerable to the ups and downs of markets. Consistent with this view that changing economic circumstances have made SOE employment appear more positive to young people, there are no statistically significant differences across age categories in responses to the query on SOE employee treatment.

Figure 5: Perceptions of Employee Treatment by Firm Ownership Type

The data reveal a strong linkage between state ownership and corruption in the minds of respondents. More than two-thirds of respondents (69 per cent) report that among firms of different ownership type operating in China, corruption was a major problem in SOEs (Figure 6). On the one hand, this strong association in the minds of respondents between SOEs and corruption is surprising given that the official ideology has long sung the praises of state ownership and emphasized the indispensability of SOEs to the national economy. On the other hand, it is not unexpected when set against the background of a parade of corruption scandals in recent years, many of which have involved SOE leaders. Indeed, the timing of the survey coincided with the busiest phase of the recent anti-corruption campaign, when a new SOE general manager was being placed under investigation virtually every week.Footnote 33

Figure 6: Perceptions of Corruption by Ownership Type

Perceptions of Market Regulation

The survey produced rich data on many aspects of the state's various interventions in the economy under the banner of market regulation. We collected information exploring respondents’ expectations with regard to the state's duties in policing and guiding markets and specifically about the degree to which there is public demand for competition policy, industrial policy, Keynesian macroeconomic management, and managing pollution. The data also allow us to compare citizens’ expectations of the state against their judgements of actual performance.

Competition policy

Our data lend insight into Chinese citizens’ views of the role of the state in providing a level playing field between firms. Here, we observe a significant gap between citizens’ expectations of the state in carrying out this role and their assessments of the state's actual performance. With regard to expectations, a large majority of respondents see the state as having a “responsibility to regulate markets to ensure fair competition between firms” – more than three-quarters of those surveyed (77 per cent) agree with this statement, and within this cohort, half “strongly agree.”

However, respondents’ expectations are evidently not always being met in the actual practice of market regulation. When prompted to evaluate the state's performance in “ensuring fair competition between state-owned enterprises and private enterprises,” more respondents disagreed (43 per cent) that the state is doing a “good job” than agreed (40 per cent). This finding resonates with debate among scholars and policy experts regarding the “advance of the state, retreat of the private sector” (guojin mintui 国进民退) after the global financial crisis and up to the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress, when the government was criticized by liberal economists for disbursing stimulus funds largely through state-owned firms and sanctioning heavy-handed takeovers of private firms by central SOEs.Footnote 34 Lending further support to the view that younger Chinese tend to hold more pro-market views, there are statistically significant differences between age categories in responses to this question, with younger respondents more likely to evaluate the state's performance critically (Appendix Table 4).

Macroeconomic management

While many respondents view the state as lacking impartiality in the domain of competition policy, respondents were, on the whole, quite positive about the state's role as the manager of economic crises. Responses to two questions show that most citizens are highly supportive of interventionist measures in times of significant economic stress. Nearly 80 per cent of respondents expressed implicit support for Keynesian crisis management approaches in agreeing that it is the “state's responsibility to stimulate the economy during an economic crisis.” A large majority (71 per cent) further believed that “there are key enterprises, whether state-owned or privately owned, that are too big or important to fail, notably during an economic crisis.” Moreover, there is strong alignment between the expectations of the state and perceptions of its actual performance as crisis manager. Echoing widespread praise of China's macroeconomic management during the global financial crisis, 71 per cent of respondents agreed that “the state effectively managed China's domestic economy from the recent global economic crisis.”

Industrial policy

The broad support for interventionist measures extends to the expected role of the state in nurturing domestic firms through industrial policy. The vast majority of respondents believe that the state has a duty to support Chinese firms in their efforts to become global players. An overwhelming majority of 87 per cent of respondents agreed that “it is important for the state to develop and encourage a group of globally competitive large enterprises to compete in global markets.” This aligns with a finding of strong nationalist sentiment about Chinese firms “going out” into overseas markets (Figure 7). Together, the two results suggest that a vast majority of people expect the government to play the role of “developmental state.”Footnote 35 Further, they also see China's developmental state as functioning well.

Figure 7: Nationalist Sentiment Regarding Chinese Firms’ Going Out

Figure 8: Perceptions of Environmental Protection

Managing negative externalities

Another dimension of the state's regulatory role, managing pollution, reveals a pronounced disconnect between respondents’ expectations of the state and their perceptions of actual performance. There appears to be a consensus within China that the state should prioritize environmental protection, even when it involves painful trade-offs. In response to the prompt, “It is the state's responsibility to protect the natural environment, even when doing so could harm economic growth,” 86 per cent of the sample agreed, with 57 per cent strongly agreeing. This belief is consistent with the government's growing emphasis on energy savings, emissions reduction and, most notably, clean air since Premier Li Keqiang's 李克强 2014 “declaration of war on pollution” (xiang wuran xuanzhan 向污染宣战). While it is widely agreed that there have been tangible improvements to environmental governance in China, the remaining gaps between official policy and actual outcomes continue to generate controversy. In analysis of who bears the blame for this “green implementation gap,”Footnote 36 local governments are most often seen as the culprits since problems of local protectionism of polluting firms and lax enforcement of environmental regulations abound.Footnote 37

When asked about the state's performance in the area of environmental protection, respondents tend to be critical and are especially so of local governments. Consistent with the widely held view that the essential failings of China's environmental system emanate from the bottom of the administrative hierarchy, respondents perceived the central level as performing the tasks of environmental protection best: 60 per cent of respondents agreed with the statement that “the state, at the central level, does a good of protecting the natural environment”; however, younger people along with residents of Beijing and Shanghai are significantly less enthusiastic in their assessments (Appendix Table 5). Relatively positive appraisals of the centre contrast sharply with respondents’ views of local governments. Less than half of respondents (46 per cent) agree that provinces are doing a “good job” of environmental protection. A note of caution is due in interpretations of these data, however, since recent dramatic improvements in air quality in China's urban coastal areas, and above all in the Jing-Jin-Ji 京津冀 region (Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei province),Footnote 38 may have already generated more positive judgements of the state's environmental performance in targeted urban areas since the time of our survey.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the Chinese public expect the state not only to perform a wide range of functions in the marketplace beyond growth promotion but also to carry out these duties fairly. While the responses convey a general demand for “inclusive” market institutions, respondents’ evaluations of actual performance point to perceptions that state interventions are sometimes “extractive” in their results. This is especially evident in citizens’ evaluations of state ownership, which can be differentiated between two things: first, the actual business and products of SOEs, which most respondents see in generally positive terms; and, second, the institutional environment surrounding state ownership, which elicits more sceptical appraisals. While the results convey a strong support for the notion of public ownership overall, younger people in particular are significantly less supportive of SOE monopolies and oligopolies in key sectors of the economy. Furthermore, more specific prompts about what exactly the state should own elicit more critical views from all respondents. Survey questions that evoke the non-market privileges that accrue to SOEs in China's state capitalist system also generate sceptical responses. As a whole, the data suggest that not all citizens are convinced of the government's oft-repeated rationales for retaining the state's “controlling force” (kongzhili 控制力) of the economy through large SOEs, particularly central-level firms.Footnote 39

Similarly, our findings on the state's regulatory functions reveal points of agreement between Chinese citizens’ expectations and evaluations of the state but also disconnects. In the former category, we find the crisis management and industrial policy functions. A large majority of citizens expect the state to intervene in markets to ward off economic crises and to give domestic firms a leg up in global competition. They also perceive the state to be performing these developmentalist functions well. Yet, significant gaps between expectations and evaluations of actual practice are evident in respondents’ opinion of competition policy and environmental protection. In each case, large majorities agree that the state has a responsibility to carry out these duties, but they see much room for improvement in the state's actual performance of these tasks. The data on competition policy echo the findings on state ownership regarding concern about the extractive characteristics of market outcomes when the state serves as both player and referee.

The significance of age in shaping judgements about state ownership and regulatory functions warrants special comment. Our results echo findings in recent studies exploring the impact of age and generational effects on views of market reform and political attitudes in China. Critical attitudes towards one of the most contentious issues in contemporary China, privatization, have been found to increase with age in “nearly a linear, monotonic fashion,” with younger people exhibiting significantly stronger pro-market orientations than older cohorts.Footnote 40 An analysis of political attitudes based on survey data collected in 2008 finds that the “one-child” generation (born in 1980 and later) show a “greater openness to considering deviations from the political/governmental status quo” in addition to a “willingness to criticize and to consider change.”Footnote 41 Our results highlighting the strength of pro-market orientations, as well as critical assessments of the practice of state ownership and regulation among the youngest respondents (all of whom belong to the “one child” generation) are consistent with Robert Harmel and Yao-Yuan Yeh's conclusions.Footnote 42 Moreover, previous work on the strength of socialist views of economic issues within the Cultural Revolution generation, particularly among former “sent down” youth,Footnote 43 helps to contextualize the sharp upswing in support for state ownership among the oldest respondents, aged 51 and above (Figure 1).

While our analysis sheds new light on citizens’ views of key economic roles of the state beyond growth promotion, future studies on this topic could focus on refining this picture. A particular shortcoming of our dataset is the absence of rural respondents and future work should sample opinion from both cities and the countryside. With regard to the possible effects of rural/urban location on perceptions of the state's economic performance, a working hypothesis is that rural respondents are less critical of state performance in the areas of market regulation and ownership. Moreover, given the significant gaps in healthcare and education outcomes between rural and urban China, rural respondents are conceivably more concerned about the quality of public goods provision. Another line of inquiry would incorporate respondents’ ideology into the analysis. One would expect respondents subscribing to a “liberal-nontraditional-market” ideology to be relatively more concerned with the fairness of state ownership and market regulation practices but perhaps less attuned to distributional matters. Respondents with an “authoritarian-traditional-nonmarket” ideology are less critical of the state's performance overall, but are more in favour of social policies to be utilized to reduce inequality. Finally, future inquiry could analyse the relative importance that citizens attach to growth promotion, public goods provision, ownership functions and market regulation to discern the state's economic functions that contribute most/least to the state's legitimation.

Conclusion

While these data reveal a baseline of support for China's economic performances in the ownership and regulation categories overall, there are also indications of dissatisfaction with the “extractive” features of China's state capitalist system. We submit that the critical edge of public opinion revealed in our analysis may be a sign of diminishing political returns to a growth-based authoritarian legitimation strategy. While the extreme hardships and suffering of the Maoist period provided fertile ground for a reformist leadership intent on renewing its right to rule on the basis of “improving the people's livelihood” (gaishan minsheng 改善民生), the great transformation that followed has brought with it roiling social change and the emergence of new values and ideologies. This is especially true of the younger generations whose views are somewhat at odds with China's state-led approach to capitalist development. Increasingly, citizens (notably younger cohorts) expect the state to provide a level playing field whereby the firms that succeed in market competition accomplish this on the basis of their merits and not their connections; what some see is a state that unfairly backs poorly run, corrupt SOEs against a non-state sector superior in management capability, efficiency and dynamism. They believe that a state should stand up for environmental protection and bring an end to growth-at-all-costs; what some see are officials providing cover to industry and turning a blind eye to hazardous levels of water, air and soil pollution. In short, growth alone appears no longer sufficient to sustain positive views of the state's economic performances. If this trend continues to the extent of threatening authoritarian stability, the lessons learned from post-Soviet states is that the state will devote more resources to maintaining their rule and less attention to governance issues.Footnote 44

Herein lies a dilemma for the Communist Party: accommodating demands for inclusive market institutions would entail deep economic reforms of the sort that would effectively dismantle state capitalism.Footnote 45 Yet, doing so could irreparably damage Party patronage networks and possibly even destabilize one-party rule. We surmise that Xi Jinping's administration has decided to forgo deep economic reform – a policy option that appeared very much on the table at the beginning of Xi's tenureFootnote 46 – in favour of shifting its weight to a legitimation strategy that focuses, first, on reducing inequality through poverty alleviation measures and social policy investments; second, on addressing citizens’ concerns about environmental crisis and health hazardous pollution; and, third, on cultivating personalist and populist appeals based on the purposive framing of Xi Jinping as a charismatic leader on a par with the “Great Helmsman” Mao Zedong 毛泽东. Our analysis might suggest that this legitimation strategy will have only limited appeal for many younger citizens. As the older generation of dyed-in-the-wool CCP supporters begins to recede from the political equation, the CCP may well find legitimation work vis-à-vis the new generation of urban elites a more arduous task.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the valuable feedback received on earlier versions of this article when it was presented at the Association for Asian Studies 2017 Annual Meeting in Toronto; the department of government, Harvard University; the European Political Science Association 2017 Annual Meeting in Milan; the Social Science Research on China Working Group of the German Association for Asian Studies 2016 Conference in Bochum; the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’École Militaire; and the University Service Center for China Studies, Chinese University of Hong Kong. We are also thankful for the helpful comments from Genia Kostka and three anonymous reviewers.

Biographical notes

Sarah EATON is professor of transregional China studies at Humboldt University Berlin. Her research interests lie in Chinese politics and political economy from comparative and transregional perspectives. Before joining Humboldt University Berlin in October 2019, she held professorships at the universities of Göttingen, Oxford and Waterloo.

Reza HASMATH is a professor in political science at the University of Alberta. He has previously held faculty positions in management, sociology and political science at the universities of Toronto, Melbourne and Oxford, and has worked for think-tanks, consultancies, development agencies and NGOs in the USA, Canada, Australia, UK and China. His award-winning research looks at evolving state–society relationships in authoritarian contexts.

Appendix

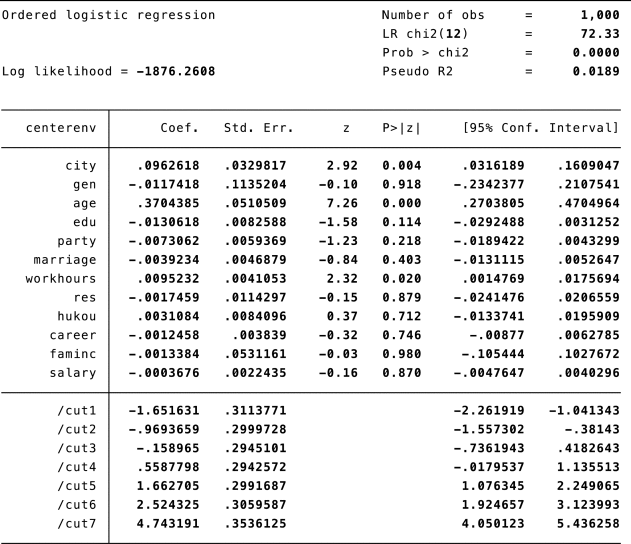

Table 1: Perceptions of State Ownership

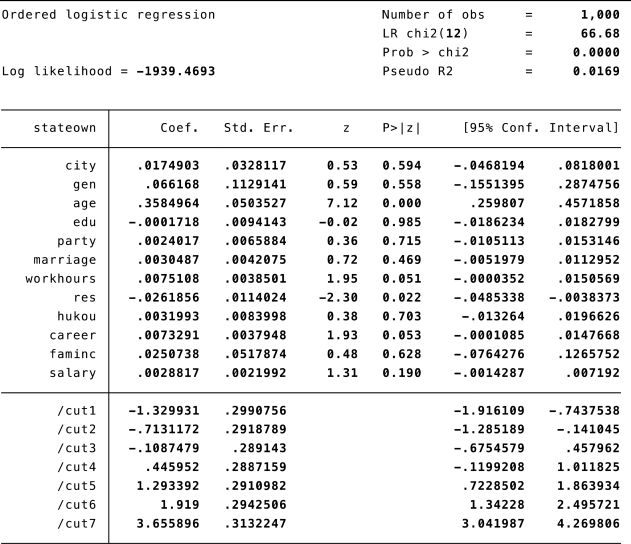

Table 2: Perceptions of SOE Management

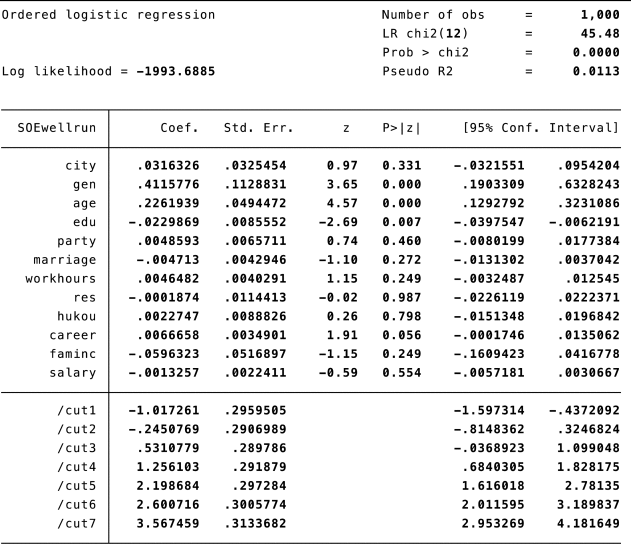

Table 3: Perceptions of SOE Products

Table 4: Perceptions of Competition Policy

Table 5: Perceptions of Centre's Environmental Performance