On arriving in the town, I was much exhausted, and for the first time since my sickness, a period of nearly five months, took some brandy. I had abstained from both wine and spirits, or other stimulants of any kind, from a mistaken notion that they were injurious: I am convinced that on that night a strong dose of brandy and opium saved my life.

Macgregor Laird, in Narrative of an Expedition into the Interior of Africa (1837)Footnote 1Previous literature on tropical medicine emphasized that doctors recommended abstinence and sobriety to Europeans travelling to warm climates in the nineteenth century.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, scholars working on the history of exploration stressed the social and psychological effects of drinking on expeditions, rather than its medical role.Footnote 3 Yet as the epigraph shows, some British explorers of Africa clearly viewed alcohol as an important – and perhaps even lifesaving – medicine. This paper examines these beliefs by responding to two questions: why did British travellers in Africa often write about drink as medicinal? What does this tell us about understandings of health and environment in this period? In answering these questions, we argue against the idea that there was a dramatic change in conceptions of tropical environments in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Scholarship often presents this period as foundational in the emergence of an ‘imperial tropical medicine’ that differed significantly from earlier approaches in presenting the diseases of warm climates as avoidable if the correct precautions were taken.Footnote 4 Such works often emphasize the importance of ‘germ theory’ in a shift away from broader climatic explanations.Footnote 5 We show that while the use of alcohol as medicine came under growing scrutiny in this period, the growing opposition to drink did not mark a theoretical shift in attitudes towards tropical environments but instead reflected the idea that alcohol was potentially a dangerous substance, and that less risky stimulants were preferable. Consequently, devoting attention to this subject allows us to offer broader insights on the development of tropical medicine and scientific views of climate. Specifically, we concentrate on drink to demonstrate continuities in medical practice in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This continuity was also expressed in the continuing importance of questions of identity and race within attitudes towards drink, with medicinal drinking often presented as the preserve of Europeans.

This paper focuses on practices around medicalized drinking on British expeditions to Africa between c.1850 and c.1910, and draws on travel advice manuals from the same period. This temporal and geographical focus is particularly revealing, as this is the era widely described as the period when modern tropical medicine emerged, at the same time as British engagement with tropical Africa grew.Footnote 6 Studying these two processes together offers insights on the relationship between political and scientific changes. We have chosen to analyse travel narratives, as there is a growing recognition that explorers and expeditions played an important role in scientific research about the human body in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 7 Explorers’ writings frequently discuss medical matters, meaning that they offer important insights into understandings of climate and health outside domestic scientific institutions. Consequently, studying their works alongside medical guidebooks allows us to focus on the discrepancy between institutional approaches to drink and lay attitudes to the subject. Some of the medical textbooks we address do also discuss other areas of the ‘tropics’, and we include such comments even though they fall outside our specific geographical focus, because they illustrate that the views of travellers in Africa were far from an aberration. We also demonstrate the diversity of thought within approaches towards drink in this period. Doctors, tropical travel ‘experts’, and frontline explorers often disagreed about the type and timing of alcohol consumption. Their debates reflect the somewhat nebulous nature of the symptoms which alcohol was used to treat, the difficulties of separating medicinal from social drinking, and the ambiguous role of many food and drink products within medical thought in this period. As such, studying this issue offers insights into changing conceptions of climate and drugs as well as the relationship between scientific theories and medical practice in the field. More broadly, we show that alcohol was an important, if contested, tropical medicine in a variety of different contexts, deserving of further attention by historians of science and medicine.

Medicinal alcohol and tropical acclimatization

Alcohol has long been used as a medicine in its own right and as a vehicle for administering other drugs. It has been used for its pain-relieving, stimulating and – in larger doses – sedative qualities. Others have used drinks because they believe they have some specific therapeutic activity, e.g. wine for digestion or brandy for shock.Footnote 8 Alcohol has been recorded in Western medicinal literature since the first century, when the Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides devoted the fifth volume of his De Materia Medica to the use of wine.Footnote 9 However, in the late eighteenth century, alcohol alone was not one of the main medical treatments used by doctors, who instead preferred ‘heroic’ interventions which produced more visible effects upon the body.Footnote 10 Such treatments included purging and bloodletting, though sometimes alcohol was paired with medicines as a solvent and a pleasant vehicle to aid their dosing.Footnote 11 The use of beverage alcohol (and particularly spirits like brandy) as a medical treatment increased over the nineteenth century due to the decline of older medical systems. Prescriptions for drinking were often a product of the idea that it had stimulating qualities, which could help to revive a patient. The Scottish physician John Brown (1735–88) was a particularly strong advocate of ‘wine therapy’ as a medical treatment, viewing it as a useful stimulant that could help rebalance the body.Footnote 12 Such practices were shaped by galenic medicinal theories, which blurred boundaries between prevention and cure. Galenical ideas were based on the view that health could be maintained by balancing inherent elements, or ‘humours’, of the body.Footnote 13 Treatments focused on heating, cooling, stimulating and sedating tissues, organs or whole bodies. The specific properties of alcohol meant it could be applied to a wide range of diseases and disorders, leaving its use up to interpretation by each user, continuously adapted depending on how, when, where and by whom it was being used. For example, smaller doses could be considered a stimulant, reviving patients, whereas larger doses could have a sedative or pain-relieving action. Other doctors thought that alcohol's stimulating qualities could help protect against diseases. In the eighteenth century, several medics argued that small doses of spirits taken before contact with a sick person could help protect against infection – an idea that the naval medic Thomas Trotter discussed (but did not endorse) in his pioneering study of drunkenness.Footnote 14

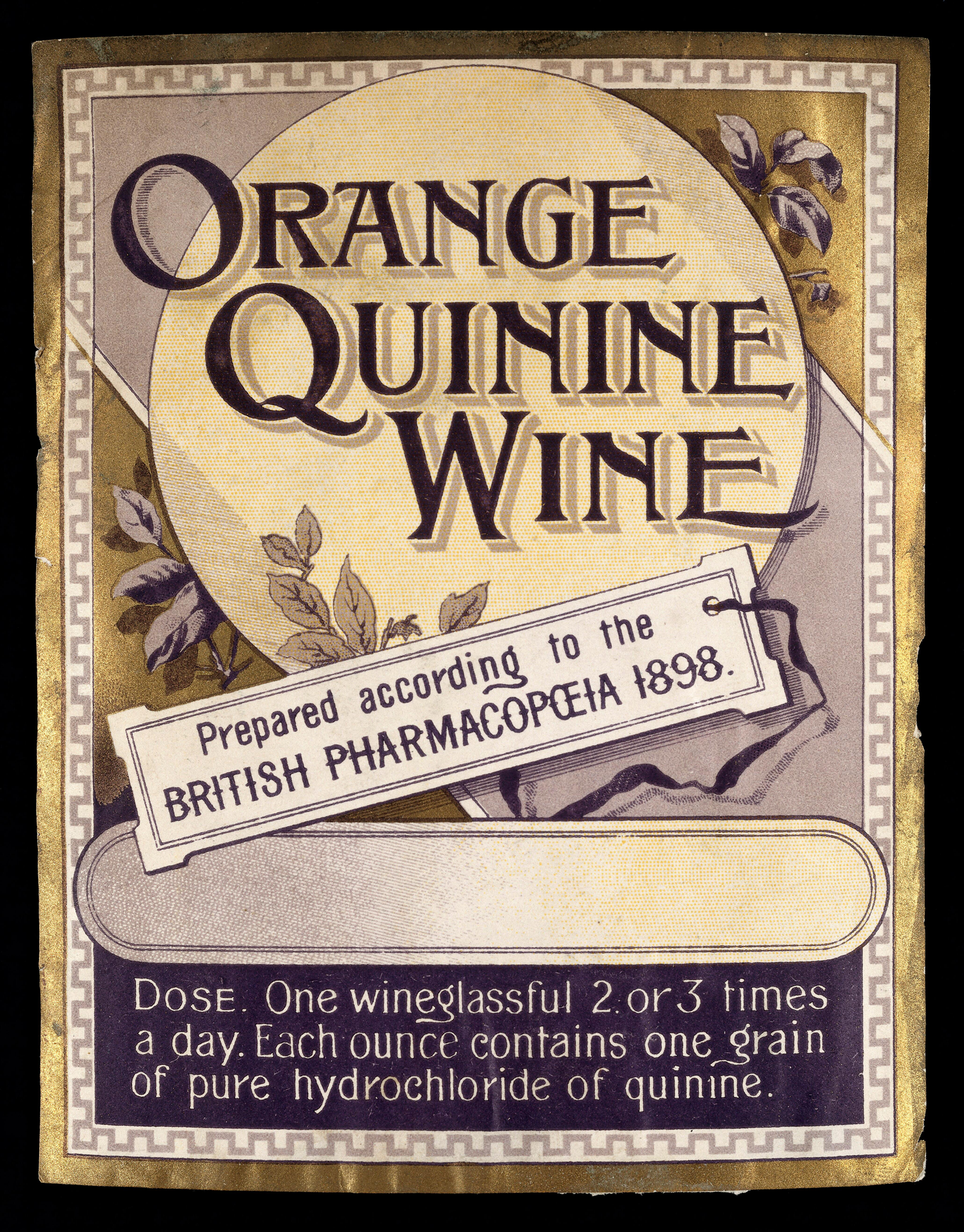

Previous scholarship leaves us with a strong understanding of changing attitudes to drink and health within Britain. From the mid-nineteenth century, ideas around the cause of infection in Western medicine gradually shifted towards a new paradigm of ‘germ theory’ and the spread of microbes as a cause of disease and infection.Footnote 15 Drug research also mirrored these developments, with more specific chemical medicines competing with more general approaches, such as tonics, which aimed to improve health in a broader sense.Footnote 16 Spirits were often used as a mixer or carrier for other medications, such as opium or quinine.Footnote 17 Indeed, quinine, the important antimalarial, was frequently administered in spirits, partly because of its ability to dissolve the quinine crystals, but also because they helped to induce the patient to take the bitter substance (see Figure 1).Footnote 18 As the century went on, alcoholic beverages were increasingly used as a medical treatment in their own right.Footnote 19 Paradoxically, this change was partly a result of the development of domestic temperance campaigns in Britain. Rooted in working-class evangelical Christianity, the temperance movement sought to change attitudes towards drinking through demonstrating its harmful effects on human health and morals. In displacing the idea that alcohol was an ordinary part of diet, the movement helped to render it a substance with ‘special’, and possibly medicinal, powers.Footnote 20 Within society more broadly, brandy was viewed as a particularly ‘medical’ drink due to its purity. It was often prescribed because of its ‘stimulating’ qualities, which increased both heart rate and blood pressure, but in larger doses it was used as a sedative.Footnote 21 The temperance movement also led a growing number of medics to adopt directly pro-abstinence views.Footnote 22 While some physicians opposed drinking altogether, others tried to find an acceptable moderate level of alcohol consumption. Most notably, Francis Edmund Anstie (1833–74) conducted experiments with brandy to try and find a ‘safe’ level of alcohol consumption. He also conducted a widely cited experiment on labouring men to see the effects of alcohol on their ability to work, concluding that alcohol harmed their production.Footnote 23 Alcohol, this research suggested, should be consumed after exercise rather than before – an idea that we see implicitly echoed in some of the discussions about tropical drinking below. This work also influenced the drinking habits of polar explorers in this period.Footnote 24 There is thus a strong scholarly understanding of the medicinal use of alcohol in Britain, but far less is known about similar practices in warm climates.Footnote 25

Figure 1. An advert for ‘Orange Quinine Wine’ illustrated the use of alcohol as a mixer for other drugs. Image used courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Conversely, while there is a significant body of scholarship on tropical medicine, little of it has devoted attention to alcohol. The advent of this branch of medicine was linked to the development of broader climatic theories and the expansion of European empires.Footnote 26 In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the idea of ‘the tropics’ as a zone that extended between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn emerged in Europe, including portions of Africa, Asia, Australasia and the Americas.Footnote 27 In grouping together these diverse environments, discourses of ‘tropicality’ emphasized the difference between these regions and ‘temperate’ zones in the north and south, and played an important role in legitimizing broader imperial ideologies.Footnote 28 The construction of these warm climates as a place uniquely different from Europe contributed to the development of tropical medicine as a specific discipline in the latter part of the nineteenth century.Footnote 29 Initially, British explorers and imperialists in Africa, Asia and the West Indies had high mortality rates, suffering from malaria, dysentery and other diseases, to the extent that tropical Africa was often referred to as ‘the white man's grave’.Footnote 30 Accordingly, these regions were constructed as uniquely dangerous to Europeans.Footnote 31 As Mark Harrison has demonstrated in the context of India, after 1800, British medics increasingly drew on climatic explanations of disease, portraying the subcontinent as a space specifically unsuitable for the white European body. Central to the debates about the ability of Europeans to live in the tropics was the question of ‘acclimatization’. Throughout the nineteenth century, some writers argued that white Europeans were inherently unsuited to warm climates – a view that was shaped by geographically racist and determinist world views that saw certain bodies as suited to certain environments.Footnote 32 Proponents argued that Europeans could not hope to spend long periods in the tropics without negative (and possibly irreversible and hereditary) effects on their physical and mental health.Footnote 33 Others argued that white bodies could adapt to life in the tropics through a process of acclimatization and ‘seasoning’ – where the body became gradually used to a new environment.Footnote 34 Schemes for protecting the European body in the tropics involved the creation of hill stations and sanatoria in which Europeans could more gradually adjust to life in India.Footnote 35 As previous scholarship has examined, proponents of European settlement suggested that strict disciplinary regimes, emphasizing exercise and diet, could reduce the negative impacts of climate.Footnote 36

Existing literatures generally agree that concerns about the effects of the tropics on the body went through several distinct phases in the nineteenth century, shaped by different theories. Initially, medics portrayed the tropics as dangerous spaces in which ‘malignant miasmas emanated from every swamp, graveyard, paddy field and jungle, summoned up by tropical humidity and a powerful sun, wafted along on insalubrious winds, or rising up in invisible clouds from rotting vegetation, human detritus, and putrid mud’.Footnote 37 Later, the identification of microbes as the cause of diseases such as malaria and cholera in the second half of the nineteenth century reduced the importance attached to climatic determinism, as it highlighted specific vectors of transmission and prevention.Footnote 38 Meanwhile, supporters of hygiene theory argued that perfect health could be preserved if the correct sanitary precautions were taken.Footnote 39 Techniques including attention to diet, exercise and hygiene were promoted to allow travellers to strengthen the body and adapt it to the climate and its influences, and alcohol was part of such discussions.Footnote 40 As the geographer David Livingstone has argued, the emerging regimes of hygiene had significant ethical dimensions, meaning that ‘the tropics were habitually presented as a moral arena. It was a risky space where circumspection and temperance were as essential to survival as acquired immunity and medication.’Footnote 41

The next major phase saw the emergence of a specific field of ‘imperial tropical medicine’ in the late nineteenth century characterized by an increasingly strong relationship between medical knowledge and colonial power. This culminated in the development of the discipline of ‘tropical medicine’ in the 1890s and 1900s by individuals such as Patrick Manson (1844–1922), who founded the London School of Tropical Medicine in 1899. As David Arnold has argued, and as we examine further below, the development of this new discipline drew on older ideas about medicine in warm climates. What changed, however, was the relationship between these medical theories and the colonial states. As Rod Edmond summarizes, ‘The new science of tropical medicine … can be understood as an attempt to put a fence around Europe and around the European in the tropics.’Footnote 42 Moreover, this ‘imperial tropical medicine’ generally involved ‘the research of vector-borne parasitic diseases in metropolitan Britain, and programmes in the tropical colonies for their control’.Footnote 43 Overall, the general trend was towards a more specific understanding of the causes of disease. However, as Harrison shows, British medics did not totally give up the belief that climate played a key factor in causing disease; many also refused to abandon the idea that different racial ‘types’ were better suited to different environments, although these ideas were inflected in different ways.Footnote 44 For example, a number of writers were concerned about the effects of the sun's rays on white skin, leading to the development of protective clothing in the latter part of the nineteenth century.Footnote 45 But even these initiatives were focused on trying to identify (and remedy) the specific factors that made warm climates unhealthy to Europeans.

Discussions of alcohol within recent scholarship on tropical medicine often emphasize the link between sobriety and health. The emphasis has been on the efforts of medics, officers and colonial administrators to deal with the problem of ‘intemperance’ amongst British travellers and soldiers, particularly ‘white subaltern’ groups.Footnote 46 Similarly, David Livingstone has briefly noted how debates about acclimatization addressed the issue of alcohol consumption.Footnote 47 More promisingly for the present study, the historian Sam Goodman has examined drinking habits in colonial India, emphasizing the paradoxical approach towards alcohol and the division between medical expertise and lay practice during the siege of Lucknow in 1857.Footnote 48 In general, as we have shown, broader literatures on tropical medicine emphasize the replacement of climatic explanations for disease by more specific preventative measures shaped by germ theory. Consequently, one would expect prescriptions for drink to decrease in the late nineteenth century. However, the picture is not so straightforward, as we now show.

Alcohol, a tropical medicine

Throughout the nineteenth century, prominent physicians prescribed certain alcoholic drinks as useful medicines when travelling in warm climates. One of the most detailed explanations for this recommendation was included in the 1883 edition of the Royal Geographical Society's travel advice manual Hints to Travellers – essentially, the guidebook on how to be an explorer. Published from the 1870s, the 1883 edition was expanded considerably and included a section titled ‘Medical hints’ authored by the British Army surgeon major George Dobson.Footnote 49 His chapter advised the would-be explorer on how to care for their body while travelling overseas, with several pages devoted to his views on drink.Footnote 50 At home, he advised against the use of ‘intoxicating liquors’, claiming that the use of them ‘rarely benefits and often proves injurious’.Footnote 51 However, in ‘tropical regions’ he argued that certain kinds of alcohol were useful for dealing with ‘the depressing effects of the climate’, which were manifested in ‘general feelings of lassitude, attended with a feeble intermitting of the pulse and a sense of sinking in the region of the heart.’Footnote 52 As Jeffrey Auerbach has argued, lethargy, boredom, and sadness were common complaints amongst European travellers, settlers and soldiers in the British Empire.Footnote 53 Now, we might view many of the symptoms described by Dobson as psychological in origin, but in his description, they are embodied through the action of both heart and pulse, showing his knowledge of the links between physical and mental health. In such situations, he advised that ‘the use of pure spirit (whisky or brandy) in small quantity, copiously diluted, acts like a charm, and may be regarded as a true medicine’.Footnote 54 He summarized his views, saying,

The writer, himself practically a teetotaller at home, has experienced abroad the benefit of the use of alcohol in moderation when travelling and collecting in tropical parts of the three great continents … continued labour, such as that of the sportsman and traveller, cannot be maintained for any length of time unassisted by the occasional and judicious use of alcohol.Footnote 55

Dobson's analysis is revealing in a number of respects. He thought about the health effects of alcohol in environmental terms. In warm climates, certain spirits could be used for their stimulating qualities, helping to combat feelings of depression and physical exhaustion. Consequently, ways of drinking that would be ill-advised, or even harmful, in a temperate climate were considered beneficial for Europeans in the tropics, helping them deal with both the physical and emotional effects of travel. Dobson's senior medical position within the British Army and his inclusion in this official publication suggest that these views were far from marginal.

Given that tropical depression was also ill-defined, alcohol was perhaps the ideal medication for its nebulous symptoms, because it had general and perceptible effects on both the mind and body of the traveller.Footnote 56 The concept of ‘medical comforts’ might be useful for understanding Dobson's prescription, though he does not use the term directly. Henry Guly defines medical comforts as ‘dietetic food for the treatment and prevention of illness … it was [also] “luxury” food and drink for ill, injured and convalescing soldiers and sailors’.Footnote 57 Certain forms of food and drink could be considered ‘medicinal’ in very general terms without being therapeutic in any more specific sense. In short, certain drinks were medicinal because they built up your strength and made you feel better. The concept of ‘stimulant tonic’ is perhaps even more revealing. Tonics were an important category of medicine that helped to ‘tone’ or strengthen the body, treating or preventing debility in general terms. Jonathan Pereira, who wrote the widely used Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics (1843), stated that ‘tonics give strength, stimulants call it forth’.Footnote 58 Certain alcoholic drinks could be both stimulants and tonics. These concepts thus help us to understand why travellers drank, if only in that they demonstrate the blurry line between food, drink and medicine in this period. The ambiguity about the ways in which drink gave an individual strength perhaps also reflected broader medical debates about how muscles actually produced energy.Footnote 59

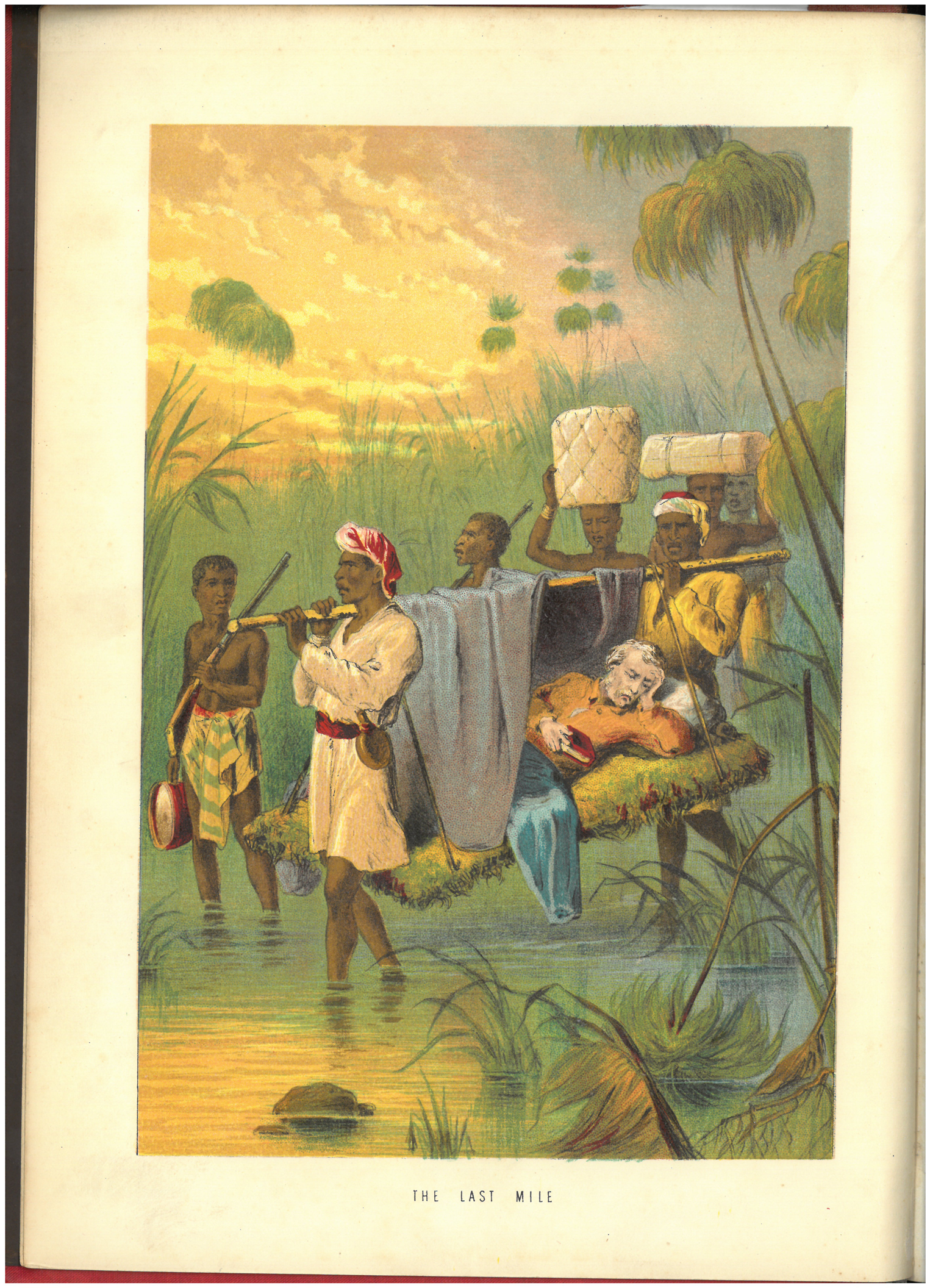

A close reading of African explorers’ accounts suggests that travellers heeded such advice. Dr David Livingstone (1813–73, Figure 2), the missionary, consul and explorer, also saw the regular but very moderate consumption of alcohol as a protection against the effects of fever. In his book about his Zambezi expedition in the late 1850s, Livingstone described its use: ‘We usually carried a bottle of brandy rolled up in our blankets, but that was used only as medicine; a spoonful in hot water before going to bed, to fend off a fever and chill.’ Again, alcohol is being used as a prophylactic, helping to protect Livingstone's body from both changes in temperature and tropical diseases. In public, he cautioned that alcohol should only be used as a preventative rather than a treatment, arguing that ‘[s]pirits always harm, if the fever has fairly begun; and it is probably that brandy-and-water had to answer for a good many deaths in Africa’.Footnote 60 In private, on another expedition, he wrote about the ‘wonderful effect’ a spoonfull of brandy mixed with hot water and sugar had on him when recovering from fever.Footnote 61 Despite including such passages, Livingstone was widely considered an exemplar of temperance. One temperance writer noted that ‘from youth in his teens up to the end of his first great journey the doctor was a consistent pledged abstainer, and if as appears … he only took it occasionally as medicine, then it may be safely said he was an abstainer to the end of his life’.Footnote 62 Such passages demonstrate how many domestic audiences – even those opposed to drink in other contexts – accepted the idea that moderate tropical drinking was genuinely medicinal.

Figure 2. ‘David Livingstone, suffering from fever, carried through the jungle by his men’, lithograph, 1874. Used courtesy of Library & Archives, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The fact that domestic audiences viewed expeditionary drinking differently was a product of travellers’ efforts to emphasize how they had only drunk in very particular ways. For instance, despite his support for the use of spirits, Dobson claimed that they must be used with ‘great caution’ – instructions echoed by other travellers who supported medical drinking.Footnote 63 Dobson also recommended that alcohol ‘should be considered a medicine, to be employed only when absolutely necessary’.Footnote 64 Similar motivations also resulted in his devoting considerable attention to the type of alcohol drunk. Alongside diluted whisky or brandy, he recommended ‘the best brands of champagne’. Claret ‘of good quality’ was also acceptable, but he complained that it ‘can rarely be obtained by the traveller’.Footnote 65 In contrast he saw beer and porter as dangerous, suggesting that they were liable to ‘provoke liver derangements’.Footnote 66 The different effects ascribed to beverages show how class hierarchies were reflected in medical knowledge. Indeed, both brandy and champagne were also used as ‘medical comforts’ on polar expeditions.Footnote 67 Dobson saw cheaper drinks as damaging, while expensive and high-quality products were portrayed as having health-giving effects. Within his writing, there seems to have been no fixed core underlying theory, apart from questions of quality and taste, dictating which drinks were beneficial. The lack of a strong explanatory theory meant that the medical value of different alcoholic beverages was an area of vigorous debate.

Mary Kingsley (1862–1900), who travelled in West Africa in the 1890s, addressed the ‘vexed question of stimulants’ in one of her books, arguing that ‘alcohol, of a proper sort, taken at proper times, and in proper quantities’, was ‘extremely valuable’.Footnote 68 Kingsley backed this claim up by citing the apparently high death rates amongst teetotal missionaries in the tropics. Her discussion focused on the relative merits of different kinds of drinks. She claimed that a ‘heavy, but sound’, red wine had positive effects, while the use of beer was linked to outbreaks of disease.Footnote 69 The explorer Captain Richard F. Burton (1821–90) was a firm believer that regularly drinking port wine helped to protect him from the effects of fever both as a solider in India and while a consul on the West Coast of Africa. He also brought brandy on the East African expedition (1856–9) but does not give much detail about how it was used.Footnote 70 Similarly, Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904) brought ‘medicinal brandy’ with him on his 1871 expedition to find Livingstone. He described brandy to local leaders as the ‘white man's beer’ and used it to treat people of colour who fell sick on expeditions.Footnote 71 Brandy and wines thus seem to have been classed as particularly medicinal drinks, but a broader reading of medical literature in this period suggests that medics prescribed different forms of alcoholic drinks for different areas and debated the merits of various beverages. An article in The Lancet by a doctor in Jamaica in 1877 stated, ‘whatever you drink, drink moderately; but don't drink brandy’.Footnote 72 In 1863, James Henderson, a writer living in Shanghai, recommended the avoidance of port and spirits, which were too heating and astringent, and instead suggested cooling and refreshing wines from the Rhine region.Footnote 73 Such contradictory advice reflects the fact that medics thought alcohol was only useful if used properly and not excessively, but they disagreed on what sorts of drinks should be consumed in different climates. Indeed, much of the advice seems to depend on personal preference rather than on any underlying medical theory.

In contrast to specifically medical drinks, African beers were seldom considered medicinal by European travellers. On the East African expedition, Burton drank much locally produced millet beer, called pombe, but he never wrote of it as having any protective effects against climate or disease. Like Burton, Stanley also distinguished between his own ‘medicinal brandy’ and locally produced alcohols, which he does not refer to as having any therapeutic or prophylactic effects.Footnote 74 This was perhaps because it was lower in alcoholic strength, and hence had weaker stimulating properties.Footnote 75 The medicinal nature of Western drinks also demonstrates the link between Western, urban-manufactured drinks and modernity, commented on by historians of drink in Africa.Footnote 76 Alcohol thus had an ambiguous position within Victorian and Edwardian medicine. Certain types of tropical drinking were clearly considered useful but many other forms were not. Distinguishing medicinal use from unacceptable and excessive drinking required attention to the type of beverage consumed and questions of frequency and location.

Overall, a significant number of Victorians saw small and properly administered doses of alcohol as an important stimulant, helping the body of the European traveller adapt to life and labour in the tropics. Some even saw alcohol as an obligatory part of a successful expedition. This view had the support of some prominent medics, but seems primarily to have been practised by travellers, explorers and soldiers despite changing scientific views of alcohol – a tenacious ‘cultural’ medicine. What type of alcohol should be consumed was a contested issue amongst medics and travellers. Such debates meant that alcohol's medicinal uses were loosely defined, the only common theme being a general rejection of beer. Nevertheless, having some preference in terms of drink does seem to have been a means of separating medicinal drinking from social consumption. Supporters of tropical drinking argued that staying healthy meant avoiding extremes: neither abstaining nor overindulging and making careful choice of specific alcohol based on its properties. Underlying this thinking were broader scientific theories about bodily and environmental difference. Medicinal drinkers viewed some sort of stimulant or tonic as necessary to help the European body cope with the strains of travel in a tropical environment. The use of alcohol in this way rested on an implicit acceptance that white bodies were ill-suited to life in Africa. Consequently, travel there required drinking in ways that would be inadvisable and even dangerous at home. While we have focused on African exploration, the influence of these theories amongst prominent explorers, soldiers and medics suggests that they were far from marginal ideas at the time.

Was African drinking medicinal?

As with ideas of tropical medicine more broadly, medical approaches to alcohol were often shaped by contemporary understandings of racial difference. A close reading of travellers’ accounts and guidebooks exposes debates over this subject. Sir Francis Galton (1822–1911), the Victorian polymath and eugenicist, seems to have shared the idea that the moderate and occasional use of alcohol was beneficial to the health of a European traveller. In his advice publication, The Art of Travel (1855), Galton advised that ‘[f]or each white man’ six pounds (2.72 kilograms, or around 3.5 litres) of brandy or rum should be taken and ‘occasionally served out’ over a sixth-month journey.Footnote 77 However, no alcohol was listed in the supplies to be taken ‘[f]or each black man’ over the same period.Footnote 78 Many of the other provisions listed are the same for both white and black travellers; alcohol is one of the only major differences. His views about drink were a product of his broader ideas about race, hierarchy and inheritance – although he does not explicitly acknowledge this. Galton viewed human capacities as innate, defined by heredity rather than environment, and used statistics to grade allegedly different ‘races’ according to perceived physical and mental capacities.Footnote 79 He argued that white Europeans had greater physical and intellectual capacities than African people with black skin.Footnote 80 The different approach to the question of brandy demonstrates how ideas about race influenced expeditionary drinking practices. In this case, Galton thought that a ‘white man’ travelling in the tropics needed brandy in a way that a ‘black man’ did not.

Explorers did occasionally give alcohol to the local African people who made their expeditions possible. As they travelled, European explorers often depended on hundreds of people to carry their supplies, and their bodies, across the continent, as well as other individuals acting as guides, intermediaries and military protection.Footnote 81 However, they seldom described their drinking as medicinal, unless the drink was administered by a white medic or expedition leader.Footnote 82 When explorers wrote about Africans and drink, it was often in racist terms highlighting incidents of drunkenness and disorder – in contrast to their own allegedly medicinal and moderate drinking.Footnote 83 As noted, Livingstone considered his own drinking medicinal. But he complained that East African Muslims he encountered on one of his expeditions frequently asked him for brandy in a ‘sly way – as medicine’, suggesting that he viewed their drinking with some suspicion.Footnote 84 What is unclear is the degree to which Livingstone viewed the dangers of alcohol in moral or medicinal terms; although, as we argue below, for many Victorian medics these two categories often overlapped. Either way, implicit in such discussions are ideas about racial difference and acclimatization. Proponents of medical drinking argued that alcohol could help white bodies cope with the depressing effects of the tropics, but suggested, for either medical or moral reasons, that it should not be used by Africans in the same way.

In general, the use of alcohol fits into the broader concern of tropical medicine with white bodies, identified by historians of the discipline.Footnote 85 Yet the writings of a few travellers, including John Hanning Speke (1827–64), do give some suggestions that the picture was not quite so binary. On his 1859–63 expedition with James Augustus Grant to the Lake Regions of central Africa, ten South African Cape Coloured riflemen of mixed heritage formed part of the expeditionary party. When David Livingstone heard about the decision, he argued that they were unlikely to ‘escape fever’ on expeditions as ‘people of colour are as liable to it as whites’.Footnote 86 Livingstone was proved right, and the men suffered severely. In his book on the expedition, Speke reported that the Cape riflemen ‘could only be kept alive by daily potions of brandy and quinine’.Footnote 87 Speke afterwards conceded that ‘if I ever travel again, I shall trust none but natives, as the climate of Africa is too trying for foreigners’.Footnote 88 That these men of mixed heritage, born in more temperate regions of the continent, were not considered ‘natives’ by Speke and used alcohol in medicinal ways suggests that in some circumstances explorers became aware of the deficiencies of broad deterministic explanations of the relationship between body, climate and health.

Kingsley was one of the few writers to write about African drinking practices in medicinal terms. She claimed that an African man also required alcoholic drinks to get ‘the stimulus that enables him to resist this vile climate’.Footnote 89 Kingsley suggested that commercial gin or rum offered these stimulating effects when consumed in small quantities.Footnote 90 In contrast, she claimed that copious quantities of locally produced palm wines had to be consumed to get the same effects, with worse physical and moral effects on the drinker.Footnote 91 On one level, these comments fit into broader demonization of both tropical climates and African people. Problems of drunkenness are presented as an inevitable product of the effects of environment. On another level, Kingsley's comments are revealing in that, unlike most other travellers, she viewed alcohol as potentially useful for Africans as well as Europeans. Moreover, she directly compares the effects of West African and European drinks, emphasizing the ‘stimulating’ qualities of the latter. Again, we see the positive role that spirits could play within medicine in the tropics. Her writings also draw further attention to the importance of questions of identity, location and type of beverage in shaping how the health effects of different drinks were understood.

The relationship between tropical drinking and ideas about white bodies and acclimatization meant that explorers seldom wrote about African drink as medicinal. There were, however, some exceptions. Speke's description of the Cape riflemen and Kingsley's accounts of West African travel suggest that at least some writers had more complex views. Again, the dominant idea seems to have been that people living or travelling in tropical environments required a stimulant to stay active and healthy. Certain forms of alcohol seemed to provide this stimulation. As we now show, even those who opposed tropical drinking did not totally reject this view.

Tropical temperance: tea, coffee and other stimulants

The use of alcohol as a prophylactic tropical medicine was consistently contested, particularly within medical circles.Footnote 92 As we now show, many physicians took the view that alcohol harmed rather than helped the European body in the tropics, while others emphasized how difficult it was to maintain a ‘moderate’ consumption. What is remarkable in studying the writings of those who opposed drinking is that they did not contest the idea that tropical travel required physical and psychological stimulants, but merely suggested that other beverages could provide this with fewer risks. Often, changing advice had more to do with shifting ideas about alcohol than revised assessments of tropical environments. The temperance movement and medical temperance writers helped to displace the idea that alcohol was a useful supply, arguing that alcohol was harmful in all circumstances. William B. Carpenter (1813–85) discussed the idea that alcohol helped to protect against the effects of tropical diseases in his influential book On the Use and Abuse of Alcoholic Liquors in Health and Disease (1850). He argued that many of the examples cited by supporters of drinking only showed that alcohol helped to protect against disease in cases where their bodies had already become dependent on it.Footnote 93 Carpenter even conceded that a stimulant might be useful in helping to protect against fever, but suggested that the same benefits could be enjoyed with fewer risks through the consumption of tea, coffee, cocoa or nourishing food.Footnote 94 Unlike proponents of tropical medicine, though, Carpenter argued that the same basic rules of good health applied in tropical, temperate or cold climates which did not differ ‘in any other particular than their temperature’.Footnote 95 In all cases, alcohol was harmful. In some senses, though, Carpenter's arguments neatly summarize one predominant approach to alcohol, not that far removed from advocates of drinking. Like them, he suggested that alcohol might be useful in some situations, but he had a different assessment of the relationship between risk and reward.

Other physicians opposed tropical drinking on the basis that these environments posed a specific threat to the white body and that it was more dangerous to drink there than at home. In his 1856 book on tropical diseases, the British military surgeon James Ranald Martin (1796–1874) advised Europeans in the tropics that to stay healthy they ‘must be temperate’, cautioning that alcohol, particularly if taken in excess, caused ‘contamination of the blood’ and predisposed the drinker to attacks of diseases.Footnote 96 These negative effects were described in specifically environmental terms: ‘the abuse of ardent spirits proves so baneful in hot climates’.Footnote 97 To be sure, Martin seems to have viewed this as a precaution against drunkenness and immoderate consumption, suggesting that he was not against giving ‘a moderate spirit ration to the seasoned soldier’ in the tropics.Footnote 98 There was also concern that alcohol reduced the ability to work effectively, a concern borne of his awareness of the depressing rather than the stimulating qualities of drink.Footnote 99 Influential military medics, such as Edmund Parkes (1819–1876), claimed that while moderate consumption of alcohol might be acceptable in some circumstances, it was not recommended in hot climates. ‘It seems quite certain’, he cautioned, that ‘not only is heat less well borne, but insolation [overheating] is predisposed to’.Footnote 100 More broadly, he advised that the tropics were specifically dangerous to the white body and questioned whether total acclimatization was possible, while still suggesting that some of these effects were in fact the result of ‘bad diet’.Footnote 101 Indeed, Parkes complained that despite the negative effects of drink, ‘nothing is more common than to hear officers, in both India and the West Indies, assert that the climate requires alcohol’, demonstrating the enduring power of this belief across the British Empire.Footnote 102 More generally, Parkes emphasized that while very small quantities of alcohol might aid digestion, drink also caused a ‘blunting of the nervous system’ and reduced an individual's muscular power.Footnote 103 His analysis of alcohol also addresses the importance of ‘moral considerations’ and emphasizes ‘the misery’ which drink produced.Footnote 104 These comments echo Livingstone's observation that regimes of hygiene were shaped by ethical as well as physical considerations.Footnote 105 As Parkes's comments show, debates about the effectiveness of alcohol focused not only on the relationship between body and environment but also on the physical and psychological qualities of alcohol as a drug. These qualities were the same everywhere but were particularly visible in the especially inhospitable tropical environment.

Moral concerns about the effects of alcohol were shaped by the expansion of European empires. Indeed, drunkenness had been a long-standing problem in British India, where many soldiers drank excessively in part because of feelings of loneliness and boredom.Footnote 106 One Edwardian report on drinking in India recorded that the average daily consumption of spirits for a ‘moderate drinker’ was between a quarter and half a bottle of spirits.Footnote 107 Drunkenness amongst Europeans exposed the mythical nature of the British ‘civilizing mission’ and authorities made efforts to confine excessive drinking to private spaces.Footnote 108 As we now show, the expansion of the British Empire into sub-Saharan Africa in the 1890s meant that similar concerns emerged in this context.

Prolonged European colonization made clear how many European residents of the continent were using the idea that alcohol protected against the effects of climate as an excuse for excessive drinking. In his travel narrative The River Congo (1895) the African explorer Sir Harry H. Johnston (1858–1927) suggested that Europeans in the tropics were drinking too much, using the medicinal properties of alcohol to excuse this overindulgence. Johnston cautioned,

The mental depression consequent on the enervating climate is more healthily dispersed by interesting and entertaining literature, especially when this is enjoyed together with a cup of fragrant coffee, than by the continual glasses of grog, the ‘nips’ of brandy, the ‘gins and bitters’ … which to react on the deadening senses, have to be continually increased in alcoholic strength.Footnote 109

As can be seen from Johnston's quote, many of the critics of drinking did not question the need for a stimulant in the tropics – but merely argued that alcohol was not the best treatment. Indeed, he clearly recognizes ‘mental depression’ as an acute problem. Like supporters of prophylactic drinking, Johnston saw warm climates as placing an inevitable strain upon a European resident. Consequently, there was a search for other suitable stimulants. He summed up his advice to Europeans in Africa by calling for ‘more books, less brandy’, and, as noted above, also wrote positively about the effects of coffee.Footnote 110 These comments again highlight the psychological as well as physical nature of tropical depression. The tropics are seen to place a strain on the mental as well as the physical health of the traveller – and treatments addressed the mind as well as the body. Johnston's assessment of drinking is not, therefore, based on a fundamentally different view of the tropical environment, but on a different assessment of alcohol as a drug. Rather than emphasizing its stimulating qualities, he saw it as desensitizing and depressing. Yet even he saw it as having some important medical uses. He wrote that ‘alcohol is simply invaluable as a tonic when weak from fever or other causes’.Footnote 111 Here, then, we again see alcohol used as a substance to build up the strength of a convalescent person – emphasizing how it might still be understood as a tonic or ‘medical comfort’, if properly used. Consequently, his recommendations again demonstrate the ambiguity of alcohol in this period and the fact that there were key points of agreement between supporters and opponents of tropical drinking.

Numerous advice manuals recommended caffeinated drinks instead of alcohol. Parkes advised that ‘warm tea’ was the best beverage in hot climates.Footnote 112 The idea that there were better alternatives was shared by Patrick Manson. His writings about alcohol show how close many of his recommendations were to earlier theories about disease prevention. In his medical manual Tropical Diseases (1898), Manson argued that ‘small doses of alcohol are of decided service’ in preventing malaria but included this advice in a section titled ‘Other prophylactics’ behind tea and coffee.Footnote 113 Manson also suggested that alcohol's effects in helping the European body adapt to the tropics might not be solely positive, advising that alcohol should only be drunk ‘in strict moderation … being taken only after the work of the day is over, and when there is no longer any necessity of going out in the sun’.Footnote 114 For Manson, alcohol was still a prophylactic, but had to be used at the right time and in strict moderation. Moreover, other beverages appeared increasingly able to play a remarkably similar role but with fewer risks. Advice for travellers given by the then late William Henry Cross (1856–92) reflected these broader changes. By 1906, William Cross was the author of the medical section of Hints to Travellers. He cautioned that ‘[e]xcess in the use of alcoholic stimulants is one of the most fatal errors into which a tropic resident can fall, and its use as a beverage is totally unnecessary, tea, coffee, and cocoa being the best beverages for ordinary use’.Footnote 115 The preference for tea and coffee over water was (at least implicitly) shaped by the fact that, being boiled, they were less likely to spread disease. The prescription of boiled drinks shows the growing influence of microbial disease causation within medical thought – a development noted by previous scholarship on tropical medicine.Footnote 116 However, we should not ignore the other substance mixed with the boiled water. The recommendation for caffeinated drinks suggests that while alcohol was no longer considered useful, stimulants or ‘medical comforts’ were still important tools for tropical travellers because of the specific strains of the climate.

The difference in emphasis between supporters and opponents of tropical drinking was relatively subtle. As noted, even advocates of drinking claimed that excesses should be avoided. Conversely, Cross prescribed brandy for a limited number of health conditions, but discouraged its use as a general aid to help deal with the strains of tropical travel. Drinking too much was also seen as something that could cause or compound other health problems. For instance, while emphasizing that dysentery was ‘caused by drinking impure water’ he suggested that ‘[a]lcoholic and other excesses render people particularly liable to contract the disease’.Footnote 117 Such advice also held for travellers on their way to the tropics. Cross argued that overindulgence in alcohol and rich foods on the ship out ‘frequently ends in the traveller arriving in a flabby bilious condition, in which state he is predisposed to attacks of malaria, dysentery, and other diseases’.Footnote 118 In part, this comment is demonstrative of a broader concern that ships travelling to the tropics were becoming spaces of intemperance.Footnote 119 However, it also reflected shifting domestic attitudes towards medical prescriptions of alcohol. As Thora Hands notes, doctors ‘came under attack from temperance campaigners both inside and outside the medical profession because a prescription to drink had medical and moral implications and by the end of the century its usage within hospitals and asylums had declined’.Footnote 120 Equally, the late nineteenth century also saw growing numbers of scientists trying to scientifically understand articles of diet and the physical effects of alcohol, which led to the reassessment of alcohol as a drug.Footnote 121 Overall, it seems that changing social and scientific understandings of drinking changed much more dramatically than did medical assessments of tropical environments.

The arguments put forward by many critics of tropical drinking suggest that both sides of this debate often had an underlying agreement that warm climates placed stress on the white body. This develops previous literature on tropical medicine which focuses on the development of specific causes of disease, such as microbes and parasites and preventive measures such as sanitation and hygiene.Footnote 122 This is certainly part of the story. However, those opposed to tropical drinking were so not because they rejected the usefulness of stimulants in the tropics or because they thought that these climates were safer. Instead, many viewed these climates as exposing alcohol's inherent dangers, which were less visible in more salubrious climates. They argued that other stimulants – tea, coffee and even, as Johnston suggested, ‘entertaining literature’ – could have similar effects as alcohol but without the same risks.Footnote 123 Both supporters and opponents often shared a similar view of the relationship between the white body and the tropical environment. Equally, the fact that medical writers had to keep repeating arguments against drink hints at the enduring cultural belief in the usefulness of alcohol in warm climates.

Conclusion

It is often tempting to view the regular and medicinal use of alcohol as a strange quirk, reflecting explorers’ taste for brandy rather than any serious medical or scientific theory. However, as we have shown, the role of alcohol in helping explorers adapt to different environments illustrates broader debates and changes within the nineteenth-century understanding of medicine, alcohol, climate, health and the body. Indeed, many explorers saw drink as a tool that helped them to deal with the physical and psychological strains of life in warm climates. They viewed its stimulating or strength-building qualities as particularly useful, helping to relieve the symptoms of exhaustion and depression. Others suggested that it actively treated and prevented certain diseases such as fever. But whether alcohol should be embraced or avoided was hotly debated over the course of the nineteenth century. What types of drink were most useful and exactly when they should be taken were also contested issues. Precisely because its status as a medicine was ambiguous, the type of alcohol used and the ways in which it was administered became important ways of separating ‘medicinal’ alcohol from more everyday drinking. Similarly, portrayals of African drinking were a source of debate. Travellers suggested that the drinking habits of African people were not medicinal, but there were a few notable exceptions, again suggesting that climatic theories of health had an important purchase. We thus suggest that ideas of racial difference and climatic adaptation were central to medical understandings of alcohol in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The importance of racism and ideas of racial difference in Victorian and Edwardian medical thinking demonstrates how early tropical medicine was far from being a universal science but devoted specific attention to white bodies.

As we have shown, medical manuals increasingly challenged the idea that spirits and wines were an aid to the tropical travellers, partly because drinking in warm climates seems to have been a common and persistent practice amongst European travellers. The reassessment of drink was a result of changing attitudes to alcohol as a drug rather than of shifting assessments of tropical climates. Indeed, most opponents of drinking in warm climates objected to the practice for the same reason as supporters advocated it: because the tropical climates placed extra strains on the white body. The debate was about the nature of alcohol as a drug rather than about the healthiness of life in hot countries. Many advocates of temperance also argued that white travellers needed some kind of stimulant to help them cope with the ‘depressing effects’ of the tropical climate. As such, our analysis foregrounds the continuities in European medical practice in warm climates in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and throws into question the idea that ‘imperial tropical medicine’ resulted in a dramatic change in underlying scientific theories around climate. This is not to say that there were not broader changes in the relationship between colonial states and medicine in this period, but these changes did not necessarily reflect a different assessment of the dangers of tropical environments. Instead, there was a shift in attitudes towards alcohol as a drug shaped by temperance campaigns and accusations of European drunkenness. Indeed, the other important point to remember is that much of the advice against drinking was a result of the apparent popularity of this remedy amongst travellers. Despite the growing opposition to drink, many British people travelling in the tropics continued to view it as useful. These ideas also had purchase within the empire more broadly, cropping up in reports on soldiers stationed in a variety of locations. Our analysis thus highlights how historians interested in the changing practices of consumption need to be attuned to the differences between medical advice given in textbooks and actual practice in the field. Many drank alcohol because it made them feel better, even if they disagreed about the exact reasons for these positive effects.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to AHRC Techne, and the Techne National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF). Additional thanks to the members of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, in particular Briony Hudson, and to the Herbal History Research Network, particularly Alison Denham, for advice. Ed Armston-Sheret would like to thank the Royal Historical Society and the Huntington Library in California for grants that made this research possible. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for perceptive comments that substantially improved this paper.