Research questions and expectations

Broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) is thought to have been introduced into Europe from Asia as early as the Neolithic period, although this has recently been challenged (see Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute et al. Reference Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute, Staff, Hunt, Liu and Jones2013). It had most probably become a cultivated crop by the Middle or Late Bronze Age (Stika & Heiss Reference Stika and Heiss2013), as its significant presence—often in the form of large deposits of grains—has been observed at some Bronze Age sites (Figure 1). Furthermore, isotopic and biomolecular evidence from this period suggests the preparation and consumption of food that included millet (e.g. Lightfoot et al. Reference Lightfoot, Liu and Jones2013; Heron et al. Reference Heron, Shoda, Barcons, Czebreszuk, Eley, Gorton, Kirleis, Kneisel, Lucquin, Müller, Nishida, Son and Craig2016).

Figure 1 Modern broomcorn millet plant and grains, and a potsherd from the Late Bronze Age site of Bruszczewo, Poland, showing imprints of millet grains (photograph courtesy of S. Jagiolla, UFG Kiel).

Innovations need time to spread and become established. Once millet had arrived in Europe, it may have taken time to recognise its potential and incorporate it into the existing annual crop-production cycle. A new crop, however, could be adopted quickly, if the social, economic and agricultural requirements were favourable (Thirsk Reference Thirsk1985: 542). Which, if either, of these two scenarios is applicable to the arrival and diffusion of millet in and across Northern Europe?

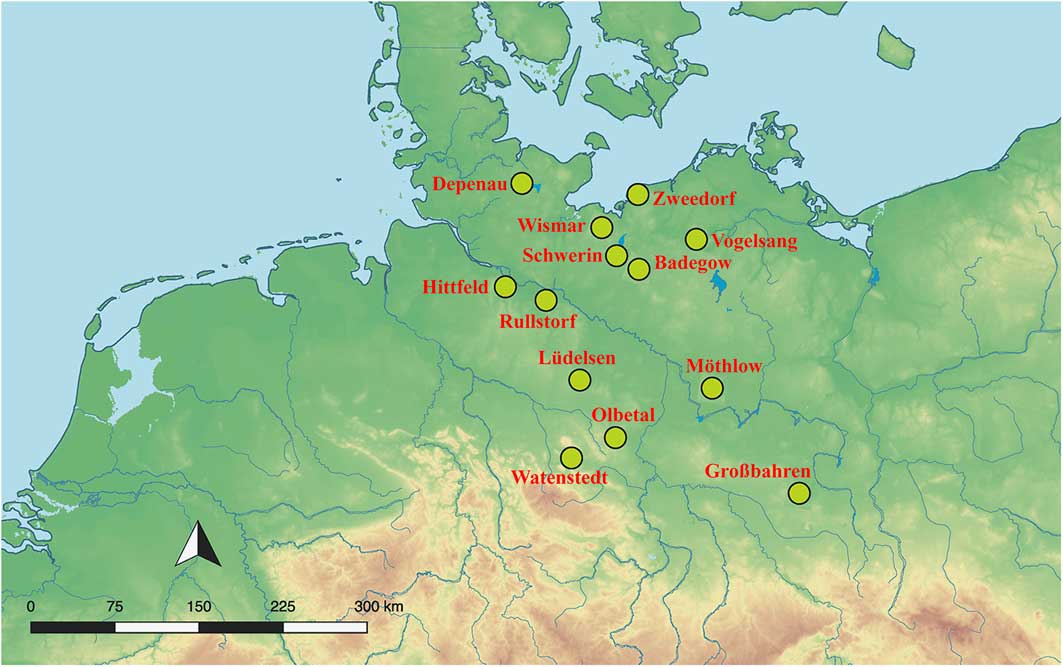

We will address this question through AMS radiocarbon dating of broomcorn millet grains recovered from Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in northern Germany (Figure 2 & Table 1). We expect these analyses to identify the earliest presence of millet in this part of the world, to estimate the ‘start date’ of millet cultivation based on the precise age of large millet deposits and to recognise potential intra-regional differences. The targeted material includes both small occurrences of millet (1–2 grains per deposit) and ‘mass’ (high-density) finds. The dating is being performed at the radiocarbon laboratories in Poznań and Kiel following standard protocols (i.e. there is no modification in pre-treatment to account for small grain size, unlike Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute et al. Reference Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute, Staff, Hunt, Liu and Jones2013). As a strict rule, single grains are dated.

Figure 2 Map showing the location of the sites that produced millet grains for dating (figure by D. Filipović).

Table 1 Northern German sites from which millet grains have been dated

Initial results and ways forward

Until now, AMS dates on single millet grains from seven Neolithic and/or Bronze Age sites have been obtained (Figure 3). Results suggest that it is unlikely that millet appeared much before 1200 cal BC—the very beginning of the Late Bronze Age in Germany. The earliest date, for now, is from the mass find of millet from Rullstorf (Figure 4); this may represent the earliest example of millet cultivation in the region (Kirleis Reference Kirleis2003). The majority of the dates are from grains deriving from small millet deposits. If deposit size is taken as reflecting the crop or no-crop status of millet, it seems as though millet was cultivated at some sites by or at the start of the Late Bronze Age, but not at others. Thus, there may not have been a general adoption of millet cultivation across the region.

Figure 3 The site of Olbetal, with Neolithic (large, triple ditch) and Bronze Age (small, single ditch) enclosures; millet grains found in both derive from the mid Late Bronze Age (photograph courtesy of C. Rinne, UFG Kiel).

Figure 4 Charred broomcorn millet grains from Rullstorf (photograph courtesy of W. Kirleis, UFG Kiel).

As broomcorn millet is a short-season plant, its sowing and harvest can take place within the summer months. Well adapted to a range of soils and climatic conditions, it is drought and heat resistant, and can grow at high or low altitudes (e.g. Miller et al. Reference Miller, Spengler and Frachetti2016). Archaeobotanical data suggest that the cultivation of several other species, including spelt wheat (Triticum spelta L.), gold of pleasure (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) and faba beans (Vicia faba L.), probably began in northern Germany in the Late Bronze Age (Effenberger Reference Effenberger2018). In this period also, weed species became more abundant and diverse across the study region (Effenberger Reference Effenberger2017). This development perhaps pertains to the addition of millet (and other ‘new’ crops) to the former (Neolithic) crop suite. It may reflect changes in agricultural practice, such as a shift to more extensive agriculture, increased variability in cultivation intensity (e.g. infield-outfield farming; Christiansen Reference Christiansen1978), and/or cropping in newly established arable areas, such as those that were waterlogged in winter and only available for summer crops (e.g. millet).

Acknowledgements

The millet dating programme is part of the ‘Dynamics of Plant Economies in Ancient Societies’ project carried out at the Institute for Pre- and Protohistory of the University of Kiel, within the Collaborative Research Centre 1266 ‘Scales of Transformation’, and is funded by the German Research Foundation. Dating is being performed at the Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory, Adam Mickiewicz University and the Leibniz-Laboratory for AMS Dating and Stable Isotope Research, Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel.