After considerable effort, the diarist Samuel Pepys and his wife, Elizabeth, finally secured seats on October 15, 1667, to the eagerly awaited production of Thomas St Serfe’s Tarugo’s Wiles: or, The Coffee House (1668). Based on a Spanish script entitled No puede ser (1661), by Agustín Moreto y Cavana, this adaptation by a “Stranger” showcased the recent urban craze for caffeinated drinks.Footnote 1 First introduced to London in 1650, coffeehouses, according to Ross W. Jamieson, grew “into the thousands” by 1700.Footnote 2 Other playwrights referenced this new fad, but no one to date had set an entire act in a coffeehouse.Footnote 3 St Serfe thus deployed a dramaturgical tactic that would become widespread in Restoration comedies: using settings and dialogue to invoke fashionable commodities, pastimes, and entertainments, thereby affiliating the theatre with the latest urban trends.Footnote 4 In The Mulberry-Garden (1668), Sir Charles Sedley draws upon the passion for landscaping, a fad William Mountfort would later exploit in Greenwich Park (1691). John Dover gestures toward a more citified space for intermingling, the recently rebuilt Pall Mall, in The Mall (1674). Thomas Southerne mocks global trade in act 3, scene 3, of The Maid’s Last Prayer; or, Any, rather than Fail (1693). Set in “Siam’s House” – an “India shop” specializing in the latest imports from Asia – the scene depicts fashionable Londoners trying to swindle the hapless shopkeeper out of her goods.Footnote 5 William Wycherley pokes fun at the popularity of dance instruction in The Gentleman Dancing Master (1673), while Edward Howard celebrates the appetite for horse racing in The Man of Newmarket (1678). Thomas Shadwell spoofs the mania for spas in Epsom-Wells (1672), as does Thomas Rawlins in Tunbridge-Wells (1678).

In addition to referencing the latest urban trends, comic playwrights stressed the timeliness of their plays by including in titles the words “fashion” and “mode,” the latter a recent addition to the English language.Footnote 6 One finds well into the next century titles such as The Damoiselles a la Mode, Marriage A-la-Mode (1671), The Man of Mode, Friendship in Fashion (1678), Courtship A-la-mode (1700), The Modish Husband (1702), The Old Mode and the New (1703), and The Fashionable Lover (1706). Creators of modish dramatic forms were especially keen to announce their embrace of the newfangled. Peter Motteux’s concoction, The Novelty: Every Act a Play (1697), encompasses five one-acts, each modeled on a different genre (pastoral, comedy, masque, farce, and tragedy) to create a mélange sufficiently innovative to have “caught the town’s fancy, and [give] Motteux two benefit nights.”Footnote 7

As an additional lure, comedies married fads to the forbidden. Like other urban spaces that encouraged transgressive social mingling, coffeehouses were lampooned for “endanger[ing] hierarchy.”Footnote 8 Tarugo’s Wiles capitalizes upon these tantalizing dangers by likening its coffeehouse to Noah’s Ark for receiving “Animals of every sort” and for serving “several Customers of all Trades and Professions.”Footnote 9 The circulation of bodies and commodities pervades the comedy. Tarugo enters the heroine’s chamber “disguis’d like a Taylor with several Indian-Stuffs,” most likely imported samples from India of calico cotton used for bedding.Footnote 10 In act 2, scene 2, the servant, Alberto, serenades the audience while “a Baboon” – another exotic import – “imitates the Musick.” Subsequently, a “Negro-Girl” joins the baboon in a dance “at the corner of the Stage.”Footnote 11 Targuo hawks coffee beans that are “the first fruits brought home from the Gardens of Sestos and Abidos,” two “Houses of Pleasure four miles from Constantinople.”Footnote 12 Virtuosi debate blood transfusions and the purchase of family arms, additional signifiers of circulation, as are the news gazettes and book advertisements mentioned in passing. Indeed, the conjunction in the play’s title specifically equates entrepreneurial wiles with the coffeehouse, that site of social and global medley. Just as Tarugo, “late arriv’d from England” via South America and the Caribbean, peddles a wide choice of international products, so does he make it possible for young characters to select their own mates in the circulating marketplace of love.Footnote 13

Despite its topicality, St Serfe’s perky tribute to coffeehouses, social mingling, and global trade did not resonate with spectators. Pepys damned the script as “the most ridiculous, insipid play that ever I saw in my life,” consoling himself that at least Thomas Betterton, the company’s much-admired star, “had no part in it” and therefore did not suffer any loss to his reputation.Footnote 14 Audiences concurred; according to John Downes, the play “[e]xpired the third Day.”Footnote 15 So utterly had Tarugo’s Wiles vanished thirteen years after its premiere that John Crowne did not even know of its existence when he set out at the behest of Charles II to write Sir Courtly Nice, yet another adaptation of No puede ser.Footnote 16 We do not know what doomed Tarugo’s Wiles – certainly, neither the plot nor the dialogue sparkles – but its fate was all too common. As the analysis of repertory in Chapter 2 argues, Restoration acting companies relied heavily on revivals and long runs. The ensuing repetition made any premiere of especial interest to spectators, as Pepys discovered when he tried to secure tickets to see Tarugo’s Wiles. Few new works were staged during the Restoration and many quickly disappeared, as occurred with Richard Flecknoe’s Love’s Kingdom, the Earl of Orrery’s Mr. Anthony (1669), Shadwell’s The Royal Shepherdess (1669), and Joseph Arrowsmith’s The Reformation (1672), to name but a few titles produced around the time of Tarugo’s Wiles. Novelty, as playwrights would discover, is ultimately self-consuming. By definition, a play can only be “novel” momentarily, especially in a culture that prized the next shiny thing, as did the Restoration. Unless a play is sufficiently powerful to catalyze the cultural and aesthetic mechanisms that ensure its place in the dramatic repertory – a dialectical process of mutual determination – an ingénue hovers in the wings, eager to replace what has grown stale.

Rapidly morphing tastes and the Restoration appetite for novelty should have resulted in a plethora of new plays that would balance revivals. As the packed premieres attest – especially of opulently produced shows – audiences craved the latest and the best. However, as Chapters 2 and 3 argue, a host of managerial decisions curbed the ability of the companies to respond dexterously to the audience desires they had primed. Complicated playhouses, high overhead, expensive stagecraft, and even more expensive dramatic operas exhausted budgets. Siting the theatres exclusively in the West End made playgoing expensive and inconvenient for anyone living outside of that immediate neighborhood. Curtain times overlapped with work schedules, while ticket prices put the theatre out of reach for most consumers. The acting companies may have chased after the culture of improvement, but they simply could not deliver on the promise of new scenes, new costumes, new effects, and, most importantly, new plays. Strapped for money and shackled by the economic logic implicit to the duopoly, the companies were hard pressed to match the surfeit of new experiences and commodities whispering alluringly to consumers outside of playhouse walls. So plenteous were the products flooding into the exchanges and so inviting the pastimes springing up around town that, for the first time, commercial theatre faced the dilemma that still bedevils it today: how to convince consumers to spend considerable money on the embodied representation of a fiction – an evanescent delight – when so many other pleasures tempt the pocketbook.

Tarugo’s Wiles exemplifies one – albeit failed – strategy for surviving the tsunami of rival urban pleasures. Referencing the latest trend, especially in a play by an unknown, was an inexpensive way to make the case that the theatre was keeping up – except that it wasn’t. For one-sixth the price of the cheapest seat to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, spectators could spend several hours in one of several hundred coffeehouses in London and read the latest political pamphlets, engage in conversation, and sip caffeinated drinks. Convenience, variety, and good value for money were precisely what emergent pastimes and entertainments such as coffeehouses, spas, parks, and music concerts offered consumers. Moreover, the purveyors of rival pleasures had more flexibility and less overhead, which in turn made it easier for them to turn a profit. Musicians could play in taverns, private homes, or specially outfitted halls; dances could be held in any sufficiently large space. The Restoration acting companies, by contrast, were permanently tethered to technologically complex playhouses that required costly maintenance and considerable manpower to operate. They also depended upon their storehouse of valuable possessions. Unlike a merchant unloading a poorly selling commodity, the companies could not liquidate the expensive assets – playbooks, costumes, scenery – necessary for their art form.

For thirty-five years, management clung to the decisions made at the outset of the Restoration about company practices and playhouse infrastructure. Why they refused for so long to change course in the face of competition and poor returns is, of course, one of the central preoccupations of this book. Behavioral economic theory suggests that optimism bias leads us to exaggerate gains while confirmation bias inclines us to make information fit our preconceptions.Footnote 17 A succession of managers may indeed have been hardwired to underestimate the threat to playgoing posed by new pastimes and commodities, but as postmodernists such as Gilles Delueze and Félix Guattari point out, historically determined conditions are also constitutive of the desire driving social production.Footnote 18 The aristocratic sheen of the duopoly and its accompanying aura of exclusivity and improvement undoubtedly contributed to managerial méconnaisance.Footnote 19 Generationality played its part too. Early in the century, few were the options for commercial entertainment, a decided advantage for acting companies that competed with bear baiting, pugilism, seasonal fairs, and taverns. Sixty years later, consumers had an unprecedented array of goods, pastimes, and entertainments upon which to spend their disposable income. Failing to acknowledge the new economic reality – in addition to internal mismanagement – collapsed the King’s Company and decimated audiences for the United Company, the sole enterprise operating in London between 1682 and 1695. That no one came forward between these years to start a second patent company suggests how etiolated demand had become. The theatre indeed was not keeping up.

Expenditures for Playgoing

Tarugo’s Wiles may have touted the benefits of global trade, but ironically, the very prosperity it extolled gave consumers in real life more choices than ever – and they were not spending that money on playgoing. Even the laboring class, according to John Spurr, “were beginning to buy more of the modest niceties of life such as knitted stockings and linen sheets, earthenware dishes and brass cooking pots.”Footnote 20 Although higher wages and falling prices produced more disposable income for consumers, most people still had to exercise considerable restraint. Hume notes in his influential article on patterns of consumption in the period that “for a very high percentage of the population of London between 1660 and 1740, a sum of, say, 5 shillings was far from negligible.”Footnote 21 According to the eighteenth-century economic theorist Jacob Vanderlint, a “family in the middling Station of Life,” a group that included a “husband, wife, four children, and one maid,” would spend £4 on entertainment out of an annual income of £315.Footnote 22 Historian Peter Earle puts the figure somewhat higher, at £16.Footnote 23

To attend a Restoration performance, a family would quickly burn through 4s. for the cheapest seats to a revival – not a premiere – and certainly not a lavishly produced machine play or dramatic opera. Oranges, an expensive playhouse treat, cost another 6d. each.Footnote 24 Hiring a hackney coach in bad weather added 12d. per hour, while traveling by boat could run anywhere from 1–4d. per person, depending on the point of departure.Footnote 25 Assuming the family used transport and treated themselves to refreshments during the show, a single excursion to the playhouse would exhaust Vanderlint’s estimated annual budget for entertainment by one-eighth. The addition of a decent tavern meal bumps that figure up to one-fourth.Footnote 26 By contrast, that same family in 1600, especially if they lived within walking distance of the amphitheatres (which many did), could attend an afternoon performance for as little as 4d. if they were willing to stand in the pit. Beer for the parents – a cheap form of playhouse refreshment that seems to have disappeared at the Restoration – would have added another 1–2d. to their bill.Footnote 27 In brief, a family of four could see a performance at the Globe, drink beer, and nibble on hazelnuts for half of what a single seat in the second gallery cost at the Restoration. Even if one accepts Earle’s more generous estimate of disposable income, a London family of comfortable means in the late seventeenth century could not afford more than one monthly outing to the theatre – and only if they were willing to sacrifice all other pleasures and superfluities.

Complaints of half-empty houses, not to mention the eventual collapse of the King’s Company, suggest that many “middling” consumers were indeed spending their money elsewhere or staying at home. The problem was this: in addition to charging exorbitant ticket prices, the companies vied increasingly with “modest niceties,” many of which were cheaper than an afternoon at the playhouse. This is not to suggest that citizens in 1600 lacked luxury goods: Linda Levy Peck put this notion to rest over a decade ago in her excellent overview of seventeenth-century consumer culture.Footnote 28 Patterns of consumption, however, changed over the course of the century in response to higher wages, lower inflation, and falling prices. Simply put, people had more money to spend on goods that had dropped steeply in price. Prior to 1620, a pound of tobacco cost 20s.–40s., making a full pipe a luxury only for the very wealthy. By the Civil War, plantation prices dropped to a penny per pound. The resulting demand by the Restoration was astronomic: importation of tobacco went from £50,000 in 1618 to £9 million in 1668, reaching upwards of £22 million by 1700.Footnote 29 So common was the craving for “the Indian Weeds” that the prologue to The Humorous Lovers (1667), the collaborative comic effort between Newcastle and Shadwell, imagines the author contentedly smoking a pipe of tobacco outside, completely oblivious to the company’s having spoken the wrong prologue.Footnote 30

The coffee drinking celebrated by St Serfe had also skyrocketed in popularity. Like tobacco, it was by the Restoration both ubiquitous and affordable. In 1663, there were over sixty coffeehouses in London; by the end of the century, that number, according to Markman Ellis, had risen to over 2,000.Footnote 31 Coffee-drinking overlapped with the intellectual production and consumption of theatrical culture and undoubtedly benefited from geographic contiguity.Footnote 32 The coffeehouses in Drury Lane and Temple Bar quickly garnered a reputation for theatrical clientele. Will’s, a coffeehouse located at the corner of Russell Street and Bow Street, was frequented by the actor Henry Harris but mainly by playwrights such as John Dryden, William Wycherley, George Etherege, and, in the 1690s, Thomas Southerne and William Congreve.Footnote 33 The growth of coffeehouses, however, was coincident not merely with theatrical life but also with the development of commercial space: both the London Stock Exchange and Lloyd’s of London began life as coffeehouses.Footnote 34 The newly rebuilt Royal Exchange in 1669 prompted the opening of several coffeehouses on nearby Lombard Street: then, as now, consumers could partake of caffeinated drinks to revive themselves for more shopping. Above all else, coffeehouses had on offer sociability, their “paramount characteristic,” according to Lawrence E. Klein.Footnote 35 Coffeehouses gave citizens, as well as writers and actors, a public space for conversing on topics of general interest and public import. They offered an additional advantage the playhouses could not rival: value for money. For one-sixth the price of the cheapest gallery seat at the playhouse, customers could participate in civic discourse while sipping at leisure a dish of coffee or hot chocolate, “pleasure goods,” in the words of S. D. Smith, possessed of “mood-altering properties.”Footnote 36

Diaries from the Restoration reveal the considerable lure of coffeehouse culture. The polymath Robert Hooke was especially entranced; he recorded “excursions to and discussions in London coffeehouses, visiting over 60 different establishments in the 1670s.”Footnote 37 By contrast, Hooke attended the patent theatres on only eight occasions over the same period, from 1672 to 1680. Personal circumstances further qualify this modest pattern of attendance: two out of eight visits were motivated by, first, the desire to verify a disturbing rumor and, second, an almost compulsive need to revisit a traumatic event.Footnote 38 On May 25, 1676, Hooke heard from Abraham Hill that Shadwell had satirized him in The Virtuoso (1676), a send-up of the Royal Society and its more outlandish experiments.Footnote 39 Hooke stayed away for a week; then, succumbing to morbid curiosity, he went to see himself represented in the figure of Sir Nicholas Gimcrack, the maddened inventor. Hooke’s rage and embarrassment spilled over into his diary (“Damned Doggs. Vindica me Deus. People almost pointed”), but, like a bystander at a car crash, he could not avert his eyes.Footnote 40 He returned to Dorset Garden a month later to see himself impersonated once again, but – understandably – future visits to the theatre ceased shortly thereafter.

Diaries and letters belie the assertion that during the Restoration “amongst most professional people and certainly gentlemen of leisure, theatre-going is too much of a habit to be noted in any but the fullest of diaries.”Footnote 41 Contemporary accounts reveal the expenditure of time as well as money that spectatorship required, and that duple investment could put off peers and professionals with other commitments. Sir John Reresby, for example, went to one of the playhouses on May 15, 1679, an activity, he notes, “which I had not leisure to take the diversion of for some time.”Footnote 42 His memoirs bear out that statement. Previously he had attended the theatre on March 19, 1678, and January 6, 1679, and drunken quarrels in the playhouse marred both visits. John Ashburnham, 1st Baron Ashburnham, attended a revival of Dryden’s Secret Love on December 14, 1686, but the performance was long (“I came home before 8 at night”) and evidently unrewarding: he irritably records in his diary that “I am now not charm’d with Playes &c.”Footnote 43 He made six more visits to the playhouse over the next six weeks, but he never once mentions enjoying a performance. Instead, Ashburnham notes whether “there was a great deal of company” and the timeliness of the show: “I came home good time a very rayny night.”Footnote 44 In his diary, Reresby states explicitly that he “had not leisure” to attend the theatre, hinting not only at the paucity of available time but also at scheduling conflicts, an issue for Hooke as well.

With one exception, Hooke attends the theatre only in the summer, a time of the year when many gentry and courtiers left London for the countryside, and establishments such as the Inns of Court and the Royal Society shut down. The acting companies responded accordingly by thinning their performance calendars with occasional revivals and the odd play by an unknown. Important scripts and expensive productions premiered in fall or winter, the same pattern still followed today in London and New York. While summer did not offer the best theatre, it was the time of year when professional demands eased. We might recall that Hooke during the 1670s held simultaneously the posts of Professor of Geometry at Gresham College, Surveyor to the City of London, and Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society, while also writing books and conducting experiments. For much of the year, he was simply too busy to bother with an art form that conflicted with work. Like Pepys, Hooke also wanted good value for money. He notes down prices paid – three shillings for the Davenant/Dryden Tempest – and he is especially annoyed when a play proves costly and offensive. Hooke finds Shadwell’s retelling of the Don Juan story in The Libertine (1676) to be an “Atheistical wicked play,” a comment in his diary followed by two spaces and the amount “2½ sh.”Footnote 45 In that gap, Hooke silently registers the displeasure convenience and variety might have mitigated.

Vying with the World of Goods

By the mid-1670s, the two licensed acting companies had rebuilt their playhouses, expanding their footprint and outfitting them with the latest technologies, as detailed in Chapter 3. They also had fresh scripts cycling into the repertory from a new generation of professional playwrights. The Restoration stage had truly arrived – except that it crashed upon the shoals of the new commodity culture. The timing was unpropitious, to put it mildly. According to Peck, the 1670s was the decade when “luxury consumption was deeply imbedded in English culture, society, and economy, despite political and religious conflict.”Footnote 46 Fine goods such as china, clocks, and looking glasses appear in the probate inventories of the lower gentry and tradesmen, as do silver and pewter objects.Footnote 47 Affordable, colorful fabrics, such as the calicoes, chintzes, and muslins imported by the East India Company, so quickened consumer desire that artisans in the 1670s were dispatched to India to show factory workers how to design patterns to English tastes.Footnote 48 By the 1690s, the importation of calicoes reached “epidemic proportions.”Footnote 49 These inexpensive fabrics, maintains Beverly Lemire, “allowed even the less affluent to own vivid, floral patterned, checked, or plaid clothing or soft furnishings.”Footnote 50 Shops stocked inexpensive, attractive products, which ensured that “not only did more people own more ordinary things, but they also chose more decorative and expressive household goods, many of them imported from the Far East.”Footnote 51

The importation of chintz and silks may have reached astronomic levels by the 1690s, but global commodities were already very much in evidence early in the Restoration. On November 16, 1665, Pepys descended into the hold of an “India Shipp” that had just docked in London. Dazed by the superfluity of goods surrounding him, he recounts seeing “pepper scatter[ed] through every chink, you trod upon it; and in cloves and nutmegs, I walked above the knees – whole rooms full – and silk in bales, and boxes of Copper-plate, one of which I saw opened.”Footnote 52 It was, he concluded, “as noble a sight as ever I saw in my life.”Footnote 53 An entry from a trade manuscript listing goods imported between October 19, 1668, and October 20, 1669, confirms Pepys’s description and again testifies to the astonishing array of global commodities pouring into Restoration London:

Almonds, almond cake, amber, aniseed, water, anchovies, apples, argal, ashes pot, balls for washing, basket rodds, coral, crystal … beads, belts, bodkin steel, books, boxes for combs, bracelets of glap and pearl, brandy, brass rings and sword hilts, brick, brushes for hair and bear, buckrams, burrs for millstones, camaletts, camlet hair, candles of tallo, milld, quilted and capps with ribbons, old woolen cards, capers, leather cases for needles … Orangeflower Water, Oyle of Turpentine, Pellitory, Pepper long, Prunella, Psylium … wrought and thrown silk, calf, goat, kidd, sheep and Spanish leather skins, screens, soap … vinegar, walnuts, watches, weld, silver wire work, wire ringes, wood for wainscoating, comb boxes, walnut tree root, whale finns, worsted and mohair yarn.Footnote 54

Even people on the lower rungs of the “middling sort” could afford many of these goods. As Keith Wrightson points out, by the Restoration many products were no longer considered to be luxuries but “decencies” that made everyday life tolerable for the masses: “more and better clothing, ceramics, clocks, mirrors, and other domestic goods.”Footnote 55

So keen was the appetite for these goods that the House of Lords Committee on the Decay of Rents and Trade recorded in 1669 that “the gentry and generality of people [were] living beyond their fortunes by which the consumptive trade is greater than that of the manufacture exported.”Footnote 56 English manufacturers complained about the imported chintzes and silk that threatened native production of wool, an understandable reaction to what Melinda Watt calls “the staggering statistics of importation between the 1660s and the 1680s” to satisfy the demand for cheaply produced foreign fabrics.Footnote 57 Farmers objected to the French food and wine that endangered their livelihood, which led to a ban on imported foodstuffs in 1678. In the meantime, the government encouraged foreign manufacturers to set up shop in England and employ local laborers to satisfy consumer demand. John Ariens van Hamme was lured from The Hague to “exercise his art of makeinge tiles, and porcelane, and other earthen wares, after the way practised in Holland.”Footnote 58 English entrepreneurship was especially encouraged. George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham – who happened to pen The Rehearsal in 1671 – secured a patent for making glass in 1663 and promptly imported Venetian workmen. On September 18, 1676, John Evelyn visited Buckingham’s glassworks factory, where he saw “huge Vasas of metal as cleare & pondrous & thick as Chrystal, also Looking-glasses far larger & better than any that come from Venice.”Footnote 59

Aside from making available tantalizing goods at an affordable price, the products pouring into London from Europe, the American colonies, and Asia offered a pleasure hitherto known only to the rich: the possibility of changing what Sara Ahmed calls “the skin of the social.”Footnote 60 Some of this pleasure had to do with refashioning social identity. If a handsomely patterned calico fabric announced a shopkeeper’s claims to ornamentation, so did decorative prints, table linens, and imported china advertise a merchant’s success. The embodied behaviors encouraged by these new products were also instrumental to creating new social identities. As Ahmed points out, objects function as “orientation devices,” moving us through space and remaking our sense of the immediate environment so that one feels “at home” or “in place.”Footnote 61 For the “middling sort” especially, the importation of inexpensive and modest luxuries changed how people extended themselves bodily and emotionally into domestic space.Footnote 62 Imported “decencies” transformed domestic spaces from utilitarian sites for sleeping, eating, and taking shelter to comfortable habitations that felt like “one’s own.” Additionally, by encouraging patterned behaviors, new products made it possible for citizens to become the gentle folk they wanted to be, shaping identity through repeated movements.Footnote 63 Navigating a room occupied solely by a large trestle table differs considerably from the delicacy of movement required by a dining room filled with tea tables, card tables, china figurines, and decorative storage pieces.

Urban spaces and architecture do the same, encouraging through repetition and habitation a sense of belonging – or estrangement. Certainly, this was true of seventeenth-century playhouses. Standing room in the Globe may have cost only a penny, but that space also gave the denizens of the yard, the so-called groundlings, the closest access to the players. From the entrances into the playhouse, they moved into a space immediately proximate to the stage, a privileged position where they could reflect back to the players their pleasure or boredom with the performance. Available light shone down through the rooftop opening on the groundlings, further illuminating their 800-strong presence for everyone in the playhouse, not just the actors. That collective visibility vanished after the Restoration. People of modest means, assuming they could afford to attend at all, retreated to the dim confines of the uppermost gallery where they were part of an anonymous mass.Footnote 64 By contrast, the privileged young men overtaking the pit – the benched area immediately in front of the stage – were now the most visible group in the auditorium, and their critical and oftentimes obnoxious pronouncements on the show were dreaded by players and playwrights alike. Expensive box seats also afforded visibility to those spectators willing to sit in “the foremost rows” who “were separated from those facing them by as little as fifteen feet, with the front rows of faces visible in the light which entered through the long rows of side windows.”Footnote 65 Effectively, wealthy spectators in boxes “sat looking at their fellows” who were framed theatrically by “the boxes and galleries opposite.”Footnote 66

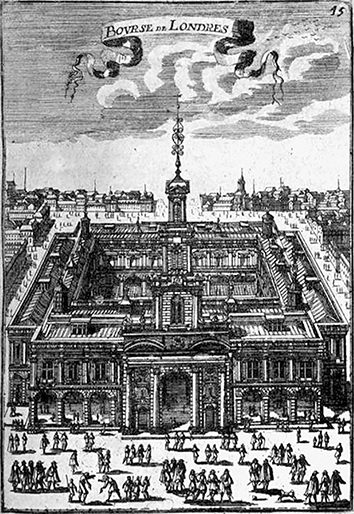

In the new enlarged, elegant shopping venues, Londoners of modest means found an opportunity for the visibility that Restoration playhouse architectural design now denied them – unless they could afford 2s. 6d. for a seat in the pit or an expensive box. Prior to the Great Fire of 1666, the Royal Exchange had featured 190 shops in the upper levels for consumers and “walks” organized around the central quadrangle for the roughly 1,000 domestic and foreign merchants involved in trade.Footnote 67 These numbers increased exponentially; by 1666, according to Richard Grassby, over 3,000 merchants “were said to frequent the Exchange.”Footnote 68 To accommodate this brisk uptick in trade and domestic consumption, the City seized the opportunity when rebuilding after the Great Fire to enlarge the footprint of the original exchange by 700 feet and increase the number of shops (Figure 4.1).Footnote 69 Additionally, expanses of plate glass were installed in both the New and Royal Exchange for the first time, an innovation that allowed consumers to gaze through shop windows after hours.Footnote 70 Increasingly shopping was not simply a necessity but a performative leisure activity, with glassed-in windows framing goods in much the same way a proscenium arch frames a performance. This time, spectators were now part of the show. Repeated amblings through public shops and walkways encouraged a very different sense of being “in place” than did the dark reaches of the upper galleries in a Restoration playhouse.

Figure 4.1 Allain Manesson Mallet, The Second Royal Exchange, 1683, book engraving

Bucolic Pleasures and Dwindling Audiences

Pleasure gardens, parks, and spas tendered new experiences, as well as choice and convenience. And, like the newly expanded exchanges, they offered citizens lovely public settings in which they could parade their newly acquired manners and clothing. The New Spring Gardens in Vauxhall was just a stone’s throw from the South Bank neighborhood, where, before the Civil War, locals could have seen plays and bear-baiting at large amphitheatres like the Globe and the Rose. Now, from any of the landing stages in Westminster, Londoners living north of the river could hire a ferryman for a half-hour crossing that would deposit them at the Vauxhall landing-stairs, just a few steps away from the entrance to the gardens. Balthasar de Monconys describes this very journey in May 1663, when he took a “boat to the other side of the Thames to see two gardens, where everyone can go and walk, have something to eat in the restaurants or in the cabins in the garden. They are called Spring Gardens, that is to say Jardin du Printemps, and the new one is more beautiful than the old.”Footnote 71 A popular attraction, the gardens drew large crowds from their inception. Evelyn records going in 1661 “to see the new Spring-Garden at Lambeth a pretty contriv’d plantation.”Footnote 72 Pepys visited on twenty-three occasions between May 1662 and July 1668 and noted with delight the crowds, the tumblers, the musicians, the nightingales, and the food for sale.

These pastimes, unlike the playhouses, were also economical. The gardens did not charge admission until the next century. The money-minded Pepys especially liked that it was not only “very pleasant” but also “cheap going thither, for a man may go to spend what he will, or nothing, all as one.”Footnote 73 That same freedom for the consumer “to spend what he will” made parks similarly attractive during fine weather, as did their ability to extend a “confidential membership” in spaces that embodied leisure as well as royal authority.Footnote 74 Charles II imported the great landscape gardener, André Le Nôtre, from Paris to extend St. James’s Park by 36 acres and lay it out anew. Once the exclusive preserve of royalty, the park, now freshly stocked with fruit trees, deer, and fowl, opened to the public after the Restoration. The park in Greenwich, although further afield, also drew Londoners to meander at will and “eat some fruit out of the King’s garden,” as did Pepys with some friends on 4 September 1665.Footnote 75 By the 1690s, parks were sufficiently fashionable among the beau monde to qualify as the first place of resort, according to The Humours, and Conversations of the Town (1693). In that popular dialogue, the typical “Beau” is imagined as first attending Covent Garden Church (assuming he can roll out of bed in time for the service), then touring the park in search of other fashionable acquaintances, and finally going to the coffeehouse. If all else fails, he then tries the playhouse, which, by 1693, was no longer the pastime of first choice.Footnote 76

Those with the means to venture outside of London could partake of racing, another pastime banned during the Interregnum that made a comeback after the Restoration. On horseback, it would have taken two days to travel to the newly expanded racing green in Newmarket, located roughly 104 kilometers outside of London.Footnote 77 A keen horseman, Charles II had to rebuild the sport from scratch, which, like playgoing, had its venues destroyed by the Puritans. Indeed, the similarities between the two forms of entertainment are striking in several respects. Charles not only rebuilt Newmarket but also drew up twenty articles of rules for the races, which was entirely unprecedented.Footnote 78 Like the patents issued to Davenant and Killigrew, these, too, detailed the codes of behavior the reinstated sport was required to uphold. And, just as he did with the London theatres, Charles not only patronized the races but also used the pastime to showcase his easygoing accessibility. He built himself a residence on Newmarket High Street in 1671, constructed a second racecourse, the Rowley Mile, named after his favorite stallion, and competed in several races, winning the Newmarket Town Plate in 1671 and 1675.Footnote 79 The races drew the court and, according to Evelyn, attracted “English gallants”: the privileged denizens of Westminster who came for their “autumnal sports.”Footnote 80 Evelyn spent a fortnight in October 1671 at Newmarket with the court, which “entertained at least 200 people and halfe as many horses, besides servants and guards at infinite expence.”Footnote 81 The Duke’s Company clearly understood how the absence of this demographic would affect their bottom line. While the court and “English gallants” bet on the horses at Newmarket, the company that fall refrained from investing in a new show. Instead, they ran Dryden’s popular (and, by then, four-year-old) comedy, Sir Martin Mar-all for thirty days straight at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.Footnote 82

Unlike the strict curtain times at performances, spas such as “Sadler’s Wells, Islington Spa, St. Pancras and Lambeth Wells, Mulberry, Marylebone, Cupers, Vauxhall, and Ranelagh Gardens” had leisure on offer.Footnote 83 These enclosed gardens and fields, according to Laura Williams, featured “the pleasures of a countrified air, al fresco eating, and pleasing prospects without straying too far from, or sacrificing, the sociability of the city.”Footnote 84 Outside of the city, Epsom and Tunbridge Wells – forerunners of Bath – rented cabins that offered city-dwellers a break from London pollution and dirty streets. The Dutch tourist William Schellink attested to the popularity of Epsom Wells, noting that it was “a very famous and much visited place, very pleasant, and that because of the water which lies not far from there in a valley, which is much drunk for health reasons.”Footnote 85 Pepys marveled at the number of “[c]itizens; which was the greatest part of the Company,” although he added, “there were some others of better Quality.”Footnote 86 He was also taken by the unstructured atmosphere: “[It] was very pleasant to see how they are there without knowing almost what to do, but only in the morning to drink waters.Footnote 87 On his second visit to Epsom Wells in July 1667, Pepys took the waters, chatted with tradesmen, then went to the King’s Head Inn for a light repast, followed by church, a big mid-day meal, and a “good nap.”Footnote 88 Later that afternoon he enjoyed with his clerk, Will Hewer, a coach ride through the countryside, a hike through woods and meadows, and an encounter with a shepherd listening to his boy read the Bible. It was, Pepys concluded, one of “the most pleasant and innocent sights that ever I saw in my life.”Footnote 89

Although Pepys may have delighted in the bucolic pleasures of Epsom Wells, playwrights like Thomas Shadwell took aim at the new pastime hiving off attendance from the playhouses. Produced in December of 1672, Epsom-Wells resurrects the well-worn comic formula whereby the “Men of Wit and Pleasure,” Raines and Bevil, humiliate country “coxcombs” – only this time in a spa setting.Footnote 90 From the outset, the play distinguishes “the life of a Gentleman” from that of “dull spleenatick sober Sots.”Footnote 91 Raines and Bevil revel in “lusty Burgundy” and boast about “the Honourable wounds we receive in Battle.” These gentlemanly attributes stand in utter contrast to the “Company … from the Wells”: Mrs. Woodly, a “Jilting, unquiet, troublesom, and very Whorish” wife; Bisket, “a quiet, humble, civil Cuckold”; Mrs. Bisket, “An impertinent imperious Strumpet”; Mrs. Jilt, “a silly affected Whore that pretends to be in Love with most men … a Pretender to Vertue”; Clopate, “a Country Justice … [and] immoderate hater of London”; and Kick and Cuff, “Two cheating, sharking, cowardly Bullies.”Footnote 92 The witty heroines, Carolina and Lucia, disparage especially the “impertinent ill-bred City-wives” frequenting Epsom Wells: these “have more trading with the youth of the Suburbs, than their Husbands with their Customers within the walls.”Footnote 93 The fashionable young men and women of the comedy disdain this new pastime, thereby confirming their gentility. Wycherley and other playwrights would use the same tactic against other forms of entertainment encroaching upon the theatre: repudiation as a marker of class status. Citizens, however, had no such compunction. In addition to revitalizing themselves at spas and strolling through pleasure gardens, they were, as the following section details, attending the vastly popular music concerts that would engulf the playhouses by the end of the century.

Music Concerts

In contrast to the expensive dramatic operas produced from the 1670s onwards were the affordable music establishments springing up throughout London. From the outset of the Restoration, music was performed for free in local taverns. Penelope Gouk lists the Mitre, just northwest of St. Paul’s, the Black Swan in Bishopsgate, and the King’s Head in Greenwich as venues visited by Pepys over the nine-year course of his diary.Footnote 94 John Harley states that the popular house at Stepney was “said to have been the resort of seafaring people, as well as others.”Footnote 95 Music concerts began as semi-private gatherings, with the composer Ben Wallington organizing the first meeting at the Mitre Inn in 1664.Footnote 96 At some music concerts, amateurs and professionals played together. In the Castle Tavern, a society of musically inclined gentlemen met for their own “private diversion,” but they also paid for several “hired base-violins … to attend them.”Footnote 97 The stationer John Playford dedicated his 1667 edition of Catch that Catch Can to “his endeared Friends of the late Musick-Society and Meeting, in the Old-Jury, London,” another private gathering of amateur and professional musicians.Footnote 98 In 1672, John Banister transformed these informal pub gatherings into commercial concerts. Six years later, Thomas Britton, a merchant coalman, followed suit in hosting “consorts” in a small room above his warehouse. These concerts provided local entertainment to Whitefriars and Clerkenwell, neighborhoods that had been served by resident playhouses prior to the Civil War. Bereft of theatre, people now had the opportunity to wander over to a tavern or private room to hear popular airs and catches or even to play along with the musicians.

Of the new music impresarios, Banister was especially savvy in capitalizing on the latest trends. He immediately seized upon the opportunity afforded by the London Gazette, one of the earliest British newspapers, to publicize his concerts. Banister placed his first advertisements in the Gazette at the end of 1672 for the musical performances he inaugurated in Whitefriars. It would, however, be another twenty-five years until the theatres placed similar advertisements in newspapers such as the Post Boy.Footnote 99 Instead, the acting companies fell back on old-fashioned means of advertising, such as announcing forthcoming shows from the stage after the play had concluded. Sometimes these were prefaced by a sung or dance; Pepys, for instance, relates how “little Mis Davis did dance a Jigg after the end of the play, and there telling the next day’s play.”Footnote 100 These announcements could backfire, especially when the discommodious reality of a bad play undermined the actor’s sales pitch. William Beeston at the end of a performance told the audience that the King’s Company would reprise Richard Flecknoe’s execrable comedy The Damoiselles a la Mode,the following day, but the play, according to Pepys, was “so mean a thing, as when they came to say it would be acted again tomorrow, both he that said it, Beeson, and the pit fell a-laughing – there being this day not a quarter of the pit full.”Footnote 101 There was an additional drawback to live announcements: the small scale of the Restoration playhouses and spotty attendance throughout the period minimized their reach.

Limited market penetration undermined the other time-honored custom used to advertise upcoming shows: plastering playbills outside the theatres and near Parliament and the Inns of Court. To check for upcoming shows, Pepys on Christmas Day in 1666 walked to the Temple, which straddled the line dividing Westminster from the westernmost limits of the City.Footnote 102 His account suggests that playbills were not plastered east of the Temple in Farringdon-without-ward or further into Billingsgate ward. These districts were home to artisans, the working poor, hospitals, prisons, markets, and slaughterhouses – a demographic largely ignored by the Restoration acting companies. By contrast, when Banister turned to advertising in the London Gazette for his music concerts, he could rely on a print run of 11,000–15,000 per issue, a rate that remained constant from 1666 to 1705.Footnote 103 He could also avail himself of the variety of outlets. Hawkers, booksellers, shipping agents, tavern and coffeehouse keepers, and government officials, as Thomas O’Malley points out, “all were involved in distributing the paper either by direct sale or through the Post Office.”Footnote 104 London received the bulk of the print run, but issues were also posted to “Newcastle, Carlisle, York, Hull, Boston, Oxford, Bristol, Gloucester, Dublin, and Paris,” which made it possible for visitors to London to plan ahead to attend a Banister concert.Footnote 105 Moreover, the first issue of the Gazette declared that it was written expressly “for the use of some Merchants and Gentlemen, who desire them.”Footnote 106 Ignored by the acting companies and mocked in comedies, these were the very consumers courted by music entrepreneurs.

Banister was clearly ambitious, but he was also motivated by acrimony. Like other members of the King’s Musick, he had been reduced to “great misery and want” over a salary that was in arrears for nearly five years.Footnote 107 Banister especially resented Charles’s well-known preference for continental musicians. Anthony à Wood records that Banister, overcome by anger, delivered “some saucy words spoken to His Majesty (viz. when he called for the Italian violins, he made answer that he had better have the English).”Footnote 108 The court retaliated by handing over management of the violins to a foreign musician, Louis Grabu, who would later collaborate with Dryden on Albion and Albanius. On February 20, 1667, Pepys visited the Duke of York’s apartments and heard “how the King’s viallin, Bannister, is mad that the King hath a Frenchman come to be chief of some part of the King’s music – at which the Duke of York made great mirth.”Footnote 109 The Duke of York’s mockery was bad enough, but Killigrew, who shared Charles’s preference for foreign musicians, may very well have had a hand in Banister’s demotion after this incident.Footnote 110 If so, it was not a good decision: Banister’s ensuing departure from the King’s Company affected the quality of their performances as well as their bottom line.Footnote 111

In a desperate attempt to replace Banister, the King’s Company jumped frenetically from one composer to another, as they sought a musical formula that might draw a steady stream of spectators.Footnote 112 Another strategy entailed throwing money at continental imports they could not afford. On October 12, 1668, Pepys went to hear the Italian eunuch Baldassare Ferri, who was featured in a new production of Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess.Footnote 113 Pepys was sufficiently enraptured with his “action as much as his singing, being both beyond all I ever saw or heard” to return two days later.Footnote 114 Well might he have hurried back: imported singers, especially eunuchs and sopranos, commanded breathtaking salaries, which meant the companies could afford them only for the briefest of runs. Moreover, their presence exerted the same paradoxical effect as expensive stagecraft and spectacle: these virtuoso singers primed audience desire for a rarified experience the companies could underwrite only for brief runs. In the case of Ferri, attendance plummeted after his departure. The following spring, when Pepys returned to see The Faithful Shepherdess – this time without Ferri – he was astonished by the contrast: “But Lord, what an empty house, there not being, as I could tell the people, so many as to make up above 10£ in the whole house.”Footnote 115 Importing continental stars might briefly shore up a wobbly box office, but short-term gain hardly compensated for the loss of an in-house composer whose talent would attract repeat visitors to the playhouse.

Unlike the Restoration acting companies, Banister did not pursue an economic policy predicated on scarcity and prestige. Rather, he made his product as inexpensive, homey, and accessible as possible. By keeping overhead low – he hosted his first concerts in his rented rooms against a tavern – Banister could offer free admission, the time-honored capitalist ploy to interest consumers in a new product. Once interest was established, he moved to larger spaces and charged a shilling for admission, the same price as the cheapest seat for a theatrical revival and certainly far less than the doubled or tripled prices for premieres or dramatic operas. Banister also moved start times from 4:00 p.m. to alternating between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m., a strategic decision in several respects. First, a later performance slot did not overlap with “Exchange time” and thus made it possible for merchants and shopkeepers to hear music after finishing business for the day. Second, a start time of 5:00 p.m. forced consumers to choose between venues insofar as the theatres would not yet have concluded their performances. And, finally, by allowing clients to have some say over the choice of musical program, Banister made audience participation part of the aesthetic experience. According to the Restoration lawyer and amateur musician Roger North, “1 s was the price and call for what you pleased.”Footnote 116 Given the fixed nature of dramatic repertory, the theatres clearly could not respond in kind.

Banister’s music concerts quickly became “well known to London society,” according to David Lasocki.Footnote 117 The advertisements Banister placed in the London Gazette indicate the rapid growth in their popularity: over the brief span of seven years, he moved to increasingly large venues to accommodate demand. He started in “the Musick-School, located over against Tavern in White Fryers,” where concerts “this present Monday, will be performed by excellent Masters, beginning precisely at 4 of the clock in the afternoon, and every afternoon for the future, precisely at the same hour.”Footnote 118 Early in 1675, Banister advertised his move to “Shandois-Street [Chandos Place], Covent-garden,” the more fashionable neighborhood first developed by the 4th Earl of Bedford in the 1630s.Footnote 119 Banister in all likelihood occupied No. 5, a large dwelling previously leased by a succession of gentlemen. It had fine woodwork and a balcony opening from the dining room, making the space an excellent setting for music concerts.Footnote 120 It was during this period that he switched to 5 and 6 p.m. curtain times. By 1678, so popular were Banister’s concerts that they were moved again to the “Essex Buildings, over against St. Clements Church in the Strand.”Footnote 121 According to A New View of London (1708), the Essex Buildings ran from Devereaux Court to the Thames, an area of 900 yards in length by 160 yards in width or 2,700 by 480 feet.Footnote 122 By contrast, Dorset Garden, the largest playhouse to date, encompassed a footprint of something like 148 by 57 feet.Footnote 123 We do not know if Banister used all of the space or a room specifically earmarked for the “Musick School.” Even so, the massive proportions of the Essex Buildings point to an ever-increasing demand for music concerts at a time when the much smaller Dorset Garden struggled to fill its auditorium. Moreover, their popularity rendered unnecessary the theatrical policy that permitted dissatisfied spectators to ask for their money back if they departed “before ye end of ye Act.”Footnote 124 There is no evidence of the same at music concerts, which hints at a profit margin the acting companies could only envy.

Contemporaries marveled at the meteoric rise of the music concerts. Roger North, an amateur musician who wrote extensively about the Restoration music scene, claimed that music concerts “shot up in to such request, as to croud out from the stage even comedy itself, and to sit downe in her place and become of such mighty value and price as wee now know it to be.”Footnote 125 By the last decade of the seventeenth century, “Consorts of Musick” could be found in Bow Street; in the York Buildings in Villiers Street; in Freeman’s Court in Cornhill; in Exeter Change in the Strand; at the Outropers-Office in the Royal Exchange; in Stationers Hall; and in Charles Street, Covent Garden. Paratexts to plays confirm North’s sense that music concerts were overtaking “even comedy itself.” A prologue written for a revival of Jonson’s Volpone (1606) imagines that if “Ben” were “now live, how would he fret, & Rage, / To see the Musick-room outvye the Stage?”Footnote 126 In 1678, the same year Banister serenaded listeners in the outsize Essex Buildings, the companies moaned about paltry audiences in their considerably smaller spaces. “Will nothing take in these Ill-natured times?”, queries the prologue to John Leanerd’s play The Rambling Justice (1678), which was produced at the struggling King’s Company.Footnote 127 In an unusually irritable prologue to Durfey’s Trick for Trick (1678), the comic actor Joe Haines, dressed “in a Red Coat like a Common Souldier,” berates audiences for their miserliness:

Lackluster attendance was hardly confined to the King’s Company, as the fate of Shadwell’s A True Widow (1678) reveals. Indeed, he was a long way from the success he had enjoyed six years earlier with Epsom-Wells. Whether due to “the Calamity of the Time” or “want of taste,” the Duke’s Company production “met not with that Success from the generality of the Audience, which I hop’d for,” as Shadwell admits in the dedication to Sir Charles Sedley.Footnote 129 The prologue written by Dryden sarcastically welcomes “Gallants … to the downfal of the Stage” and complains how “In vain our Wares on Theaters are shown, a tacit acknowledgement of the commodities with which the stage now competed.”Footnote 130

By the 1690s, music concerts, spas, and coffeehouses were no longer regarded as nipping annoyances: these now bared considerable tooth. In 1667, a newcomer like St Serfe felt sufficiently optimistic about his prospects to pet a rival pastime like coffeehouses. The same was true in 1672, when Thomas Ravenscroft gently stroked the growing fad for music concerts. In his comedy The Citizen Turn’d Gentleman (1672), Mr. Jordan, who was “formerly a Citizen, but now sets up for a Gentleman,” is urged by “Maistre Jaques” to host a weekly “Musick Club” at his house, an undertaking that “will much benefit” his upwardly mobile aspirations.Footnote 131 Twenty-five years later, Thomas Southerne would cast a far more captious eye on the beast tracking his steps. The Wives’ Excuse; or, Cuckolds Make Themselves (1692) savagely indicts the competition that has crowded out the theatre by the end of the century. The Wives’ Excuse opens in the “outward Room to the Musick-Meeting,” during which bored footmen play at hazard while mocking the concert within. In the play’s opening line, the First Footman asks, “Will this damn’d Musick-Meeting never be done? Wou’d the Cats-guts were in the Fidlers Bellies.”Footnote 132 After “[t]he Curtain drawn up, shews the Company at the Musick-Meeting,” one guest admits he “did not understand a word” of the Italian song just sung.Footnote 133 “They sung well,” corrects the play’s villain, Mr Friendall, “and that’s enough for the pleasure of the ear.”Footnote 134 Friendall’s preference for luscious sound detached from meaning emerges again later in the scene, when he commands the Musick-Master to “sing the Ladies the Song I gave him,” an impossible demand given that the “Words are so abominably out of the way of Musick.”Footnote 135

The concert that opens The Wives’ Excuse functions as Southerne’s shorthand for everything aesthetically and morally wrong with contemporary tastes, which elevate foreign music over native drama and licentiousness over decency. Tough-minded plays written in English have the potential to teach lessons, whereas the incomprehensible songs in Italian favored by Mr Friendall please only the ear. Southerne claims with a straight face in the dedication to Thomas Wharton that he introduced the device of the music meeting “as a fashionable Scene of bringing good Company together, without a design of abusing what every body likes; being in my Temper so far from disturbing a publick Pleasure, that I wou’d establish twenty more of ’em, if I cou’d.”Footnote 136 The dim auditors, the footmen’s acid commentary, and the concert-loving villain nonetheless belie this disclaimer. “Abusing what every body likes” – the music concerts that prevailed by the 1690s – is precisely what Southerne serves up in a comedy so acrid that it lay dormant for centuries.

Others shared Southerne’s resentment at the incursion of music and dance. Thomas Brown complained in a letter written on September 12, 1699, to George Moult that “an author will not much trouble himself about his thoughts and language, so he is but in fee with the dancing-masters, and has a few luscious songs to lard his dry compositions.”Footnote 137 The patent companies, according to Brown, “set so small a value on good sense, and so great a one on trifles that have no relation to the play” that it is as though “Smithfield had removed into Drury-lane and Lincolns-Inn-Fields.”Footnote 138 Even Thomas Durfey, who had happily composed songs for the stage since the 1670s, shifted his attentions toward the increasingly popular music concerts. In 1694, he dedicated The Songs to The New Play of Don Quixote to the “Much Honoured and Ingenious Friends (Lovers of MUSICK) That frequent the Rose, Chocolate-house, Coffee-houses, and other places of Credit, in and about Covent-Garden.”Footnote 139 He pointedly did not dedicate the play to anyone at the United Company. Indeed, in the preface to part 3, Durfey claims that even though he had “prepar’d by my indefatigable Diligence, Care, [and] Pains … [t]he Songish Part which I used to succeed so well in, by the indifferent performance the first day, and the hurrying it on so soon, being straitned in time thro’ ill management … was consequently not pleasing.”Footnote 140 The contrast between the dedication to the “ingenious Lovers of MUSICK” participating in music meetings around town and the blame leveled at the United Company could not be more striking. Although Durfey would go on to pen several more plays, including The Famous History of the Rise and Fall of Massaniello (1699–1700), he turned increasingly to poetry, stories, translations, and the songs that would sustain his final years.

Amateur Music and Dance

The theatre competed not only with these vastly popular commercial concerts but also with private musical performances. Invited guests could hear the very best English and foreign musicians play at the homes of nobility and gentry. Henry Purcell performed at the London home of Francis North, 1st Baron Guilford and the brother of Roger, who would prove an invaluable source of information about music in the period.Footnote 141 Musical celebrities, as Ian Spink points out, frequently augmented their public concerts with private appearances.Footnote 142 John Evelyn, who liked music far more than the theatre, attended concerts at the homes of Henry Howard, Earl of Norwich, and Sir Joseph Williamson, among others. On December 1, 1674, he was especially delighted to hear several luminaries of the music world perform at the home of Henry Slingsby.Footnote 143 Pepys, too, was ardent about the contemporary musical scene. Tellingly, when Pepys invited actors from the King’s Company to sup at his home, it was exclusively for their musical abilities. Several times he records large, festive meals followed by singing and dancing, as occurred on January 24 and May 29, 1667, and January 6, March 23, March 26, April 26, and August 26, 1668. Invariably present were Henry Harris, one of the leads (and eventual co-managers) of the Duke’s Company, and Elizabeth Knepp, a star of the King’s Company known for her fine voice. On New Year’s Day 1666, Pepys first heard Knepp sing privately “her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen.”Footnote 144 Never does Pepys seek out assistance from actors in memorizing a passage from a play, but he asks playhouse musicians to help him procure and learn scores. On January 22, 1667, “Darnell the Fidler,” one of the violinists at the Duke’s Company, offered to get for Pepys “the music of The Siege of Rhodes.”Footnote 145 On another occasion, he asked Banister, who attended several of Pepys’s private soirées, to “prick me down the notes of the Echo in The Tempest.”Footnote 146 By the 1670s, Pepys had largely given over playgoing; however, for the remainder of his life he would collect music avidly, especially ballads.Footnote 147

According to Bryan White, scholarly focus on court sponsored “polite arts,” such as theatre and painting, has overshadowed the extent to which the business community supported and consumed amateur music during the Restoration.Footnote 148 The City audience that Killigrew claimed had largely abandoned the playhouses after the Great Fire were very much involved in the burgeoning music scene. The merchant segment of that audience that “made music together also shared commercial interests,” and the resulting sociability “fostered personal networks in a community for which the exchange of information was of crucial importance.”Footnote 149 At the upper end of the economic scale, wealthy Levant merchants such as Rowland Sherman and Philip Wheak were members of the “Gentlemen of the Musical Society” that sponsored an annual feast at Stationers’ Hall celebrating St. Cecilia, the patron saint of music.Footnote 150 They also acquired instruments and skills abroad; Rowland, for instance, learned to play continuo from Catholic missionaries while he was in Aleppo.Footnote 151 Networks encompassing mutual business and musical interests often crossed class boundaries. The Old-Jewry “Musick-Society,” celebrated by John Playford in the dedication to his 1667 The Musical Companion, numbered among its membership gentlemen, merchants, and artisans, including a cloth worker, a goldsmith, and an apothecary.Footnote 152 At the other end of the social scale were everyday people looking for musical diversion. The narrator of The London Spy (1703) describes how he and a schoolfellow entered a tavern and came upon “half a Dozen of my Friends Associates, in the height of their Jollitry … After a Friendly Salutation, free from all Foppish Ceremonies, down we sat … my Friend and I contributed our Mites to add to the Treasure of our Felicity. Songs and Catches Crown’d the Night, and each Man in his Turn pleased his Ears with his own Harmony.”Footnote 153 Ward emphasizes the homeliness of the setting: these are common people, “free from all Foppish Ceremonies,” playing popular tunes and catches, the latter a simple type of round that entails two or three voices singing the same melody at different times.

The ubiquity of musical instruments by the Restoration made possible the sort of spontaneous “Jollitry” that Ward describes taking place in taverns. Their relative affordability also accelerated the making of music at home, a way to avoid muddy streets filled with ruffians or playhouses packed with pickpockets. For these additional reasons, as John Harley observes, “music was, indeed, a familiar thing in many Restoration homes … in a well-known passage Roger North … testified to the great sport of music in private society, ‘for many chose to fidle at home, then to goe out and be knockt on the head abroad.’”Footnote 154 In his peregrinations around London, Pepys heard music in churches and in homes: he estimated that one in three houses owned a virginal.Footnote 155 He also heard street organs, harps, dulcimers, bagpipes, whistles, guitars, drums, and trumpets, both in the streets and wafting through open windows of homes.Footnote 156 Amateur musicians played flageolets, a wind instrument Pepys took up in 1667, as well as guitars.Footnote 157 Especially popular were recorders, which did not require reeds or special embouchure, nor did they fatigue amateur players.Footnote 158 In 1673, the introduction of the late-style baroque recorder from France into London so heightened demand that Peter Bressan, famed for making these fine instruments, later testified in a lawsuit how the manufacture of “musical instruments and particularly of recorders” built his reputation and fortune.Footnote 159

The rapid development of music publishing provided inexpensive sheet music for these new purchasers of instruments.Footnote 160 Stephanie Louise Carter demonstrates that of the 159 titles of English printed music books in the period, over 70 percent “appear to have been primarily conceived for the amateur musician.”Footnote 161 Many of these amateur musicians were complete novices, relying on “printed beginner instrumental lesson books” designed for both sexes.Footnote 162 To further accessibility for the middling sort, Playford shifted “the musical content of his books away from repertory that required the relatively high level of skill characteristic of early seventeenth-century printed music toward simpler material.”Footnote 163 Price and iterability further enhanced the appeal of print music. Most commercial editions cost between 2s. and 4s., which meant that, for less than the cheapest seat to a dramatic opera, a consumer could own a book of scores to be played repeatedly at home. Elaborate publications, such as Louis Grabu’s score for Albion and Albanius, were advertised to subscribers at one guinea, half the price of an equivalent subscription to Dryden’s The Works of Virgil (1697).Footnote 164 Ballads retailed for a halfpenny to a penny each and thus proved far more affordable than the cost of either a play quarto or a gallery seat at the playhouse.Footnote 165

Given what we know about the demographics of late seventeenth-century England, with no more than 5 percent of the population possessing “the money to buy any but the cheapest books,” it would stand to reason that expensive music publications would languish in bookshops.Footnote 166 So keen was the demand, however, that even pricey tomes sold quickly. On December 11, 1676, the London Gazette advertised the publication of Nicola Matteis’s airs for violin and bass, which were “cut at the Desire, and Charge of certain well-wishers to the Work.”Footnote 167 Two months later, the first run was nearly gone. Consumers were informed that “the Musick Books of the first Impression of S. Nichola Matteis are almost all sold; and the remainder of them will be disposed of at 12s. a Book; or the first Part only, at 7s” before the second imprint appeared.Footnote 168 For that same 12 s., a middling family of four could attend the playhouse three times over the course of a year – but only if they purchased the cheapest seats and avoided refreshments. Theatrical performances, of course, were also one-off experiences unlike the iterability of a music book. Moreover, books retained value insofar as they could later be sold or bartered. Before he achieved prosperity, Pepys oftentimes swapped books with publishers or put used ones toward the purchase price of a new book of music: “I went to Playfords; and for two books that I had and 6s. 6d. to boot, I had my great book of songs, which he sells always for 14s.”Footnote 169 Playford also appears to have lent expensive books for a fee.Footnote 170 Certainly, his books of songs were ubiquitous by the end of the century. North describes entering a tavern near St. Paul’s and realizing that “their musick was chiefly out of Playford’s Catch Book.” This he took as “an inclination of the citisens to follow musick.”Footnote 171

Dance also spread rapidly after the Restoration, yet another non-theatrical diversion for gentry and citizens with disposable income. Pepys records seeing dancing schools in Broad Street, Fleet Street, “the city,” and even in the town of Bow, a hamlet in Stepney, Middlesex.Footnote 172 The desire to move well and execute a finely turned coranto was so pervasive that Wycherley spoofed it in The Gentleman Dancing-Master. Like Shadwell’s Epsom-Wells, which appeared just a few months later, The Gentleman Dancing-Master signaled its timeliness by referencing a contemporary urban fad it would defensively denigrate. Just as the witty, privileged young gentlemen in Epsom-Wells refrain from taking the waters – thereby distinguishing themselves from vulgar citizens – so do gentlemen in The Gentleman Dancing-Master pointedly refuse to learn how to dance. That social distinction is made abundantly clear throughout: Mr Parris (or “Monsieur De Paris”), a “rich City-Heir,” and Don Diego, an “old rich Spanish Merchant,” obsess about the social requirement to dance well. Mr Parris, for instance, vows “he wou’d never marry a Wife who cou’d not dance a Corant.”Footnote 173 By contrast, Garrard, the “Gentlem[a]n of the Town” intent on secreting away Hippolita, disdains this fashionable pastime and worries about impersonating a dancing master convincingly since “I know not a step, I cou’d never dance.”Footnote 174 Dancing schools come in for their share of abuse as well. Don Diego sends his daughter Hippolita to an academy that will “furnish [her] with terms of the Art” but not basic literacy: she cannot write a coherent sentence. Even the dance instruction seems questionable insofar as Hippolita has already forgotten the “Corant” she learned the previous year.Footnote 175 As for the purveyors of dance instruction, “are they not,” as Don Diego queries, “better dress’d and prouder than many a good Gentleman?”Footnote 176 The comic action, however, frames the oxymoron implicit in the title of the play: one cannot be a dancing master and a gentleman.

Wycherley had good reason to pillory this rival pastime, which was increasingly being taken up by rising government factotums such as Pepys. On April 25, 1663, the diarist retained the expensive dancing master, Mr Pembleton, for lessons, initially for his wife, Elizabeth, and then for himself. Although Pepys grumbled at the cost – a down payment or “entry money” of 10s. alone – and eventually suspected a flirtation between Pembleton and his wife, he nonetheless felt dancing to be so important a social skill that he continued lessons for over a year. Dancing, he reasoned, “is a thing very useful for any gentleman and sometimes I may have occasion of using it,” a statement that sounds precariously close to the views expressed by Don Diego in The Gentleman Dancing-Master.Footnote 177 This moment in the diary also provides insight into the choices even well-paid civil servants like Pepys made when deciding how to spend disposable income. He complains that the music lessons “cost me, which I am heartily sorry it should” but resolves, “to get it up some other way.”Footnote 178 One “other way” to offset the expense of dance lessons was to cut back on trips to the playhouse. Prior to hiring Pembleton, Pepys attended the patent theatres at a frenetic pace and made fifty-nine trips to the King’s Company and forty-five to the Duke’s Company between October 1660 and March 1663, for a total of 104 visits over two and a half years. Over the period of Pembleton’s employment, Pepys attended the patent theatres only thirteen times, a diminution of spectatorship that allowed him to recoup the cost of dancing lessons and focus on his career. Then, as now, consumers selected amongst pastimes and commodities: most could not afford everything on offer.

The Dividends and Drawbacks of Intermediality

In several respects, the burgeoning music industry benefited the acting companies. Certainly, the circulation of talent between venues produced delightful results, from the incidental theatre music created by talented composers such as John Eccles and John Blow to the overtures, suites, and songs devised by the brilliant Henry Purcell for his dramatic operas. With the exception of the aggrieved John Banister, composers set music for the court, for the theatres, for the churches, and, of course, for the music concerts. Music and dance instruction showcased talent the acting companies were quick to secret away. Prior to employing Pembleton, Pepys in 1662 hired a Mrs Gosnell, “who dances finely,” to instruct his wife.Footnote 179 Gosnell’s skills also caught the eye of the Duke’s Company, which hired her shortly thereafter to act, sing, and dance in their shows.Footnote 180 After Josiah Priest staged at his girls’ school in Chelsea a successful production of the dramatic opera Dido and Aeneas (1689), the United Company employed him to set the dances for Betterton’s adaptation of The Prophetess (1690), for the Dryden/Purcell opera, King Arthur (1691), and for Purcell’s follow-up opera, The Fairy Queen.Footnote 181 Performers moonlighted as teachers, instructing professionals and peers alike in the art of public speaking.Footnote 182 Intermediality also offered opportunities for popular songwriters to feature their music in plays. Durfey inserted songs into his crowd-pleasing farces whenever possible. A Fond Husband; or, The Plotting Sisters opens with the maid, Betty, serenading the errant lovers, Emilia and Rashley, with an erotic song as a backdrop to their “roving and uncontrolled way of love.”Footnote 183 Dryden borrowed this device the following year for The Kind Keeper; or, Mr. Limberham. At the beginning of act 3, the maid, Judith, who “sings at sight,” performs a “SONG from the ITALIAN” accompanied by onstage “Musick.”Footnote 184 As with modern musicals, the barest of pretexts – such as singing maids – occasioned a tuneful break in the action.

Both companies understood the need to keep up with the newest trends in music. When Killigrew crowed to Pepys about the improvements he had wrought since the outset of the Restoration, high on his list was the replacement of “two or three fiddlers” with a minimum of ten properly trained musicians.Footnote 185 He also fantasized about erecting another playhouse in Moorfields that would produce opera on a regular basis, thus positioning London as a musical destination site equivalent to Venice.Footnote 186 Although the theatre was never built – money again – both companies realized their ambition of larger, better-equipped musical ensembles, which were sometimes augmented by violinists on loan from the King’s Musick. Certainly, larger ensembles made it possible for spectators to enjoy more complex compositions, such as the two contrasting instrumental pieces, known as the “first” and “second musick,” before the overture.Footnote 187 As Kathryn Lowerre notes, of the nine pieces customarily played as part of a Restoration performance, these first two showcased the latest developments in instrumentation and vocalization.Footnote 188 Specially composed act tunes, which helped muffle the sound of scene changes, provided additional diversion between the acts.Footnote 189 Between 1660 and 1705, overlap between the worlds of theatre and music resulted in over 600 stage works, including operas and masques, that incorporated songs and instrumental pieces into theatrical performance.Footnote 190

Intermediality undoubtedly enhanced playgoing, but it also added enormously to production costs. High salaries made dramatic operas and imported singers the most occasional of treats. As such, they hardly vied with the music concerts that by the late 1670s were held at least once, if not twice, a week at increasingly large venues around London. At Dorset Garden, only three dramatic operas were staged in the 1670s (The Tempest, Psyche, and Circe), one in the 1680s (Albion and Albanius), and three in the 1690s (The Prophetess, King Arthur, and The Fairy Queen). Repetition dogged theatre music as much as it did stagecraft and repertory. Incidental music was composed for new works exclusively, and too often act tunes were “all but indistinguishable from others.”Footnote 191 Even the migration of popular theatrical tunes into published collections, such as Covent Garden Drollery (1672), failed to benefit the companies. If anything, divorcing music from live performance worked far more to the economic advantage of publishers. Songs in theatrical performances effectively functioned as promotionals in the 1670s and 1680s for enterprising publishers such as John Carr, John Playford, and his son, Henry Playford. Spectators enamored of a Durfey song they saw performed on stage could purchase the score in the new, easy-to-read format increasingly marketed during the Restoration. They could subsequently play these tunes repeatedly at their homes rather than spending a shilling to listen to an ensemble play them at the theatre.

The Playfords were exceptionally quick to cannibalize live theatre for their own ends. John Playford’s Choice Songs and Ayres for One Voyce to Sing to a Theorbo-Lute, or Bass-Viol (1673) was the first to advertise on its title page “Most of the Newest SONGS Sung at Court, and at the Public THEATRES.” The volume featured simple music notation that would make it possible for an amateur to sing what she had heard in Dorset Garden while accompanied by a lute or bass-viol, both popular instruments for domestic use. Choice Songs and Ayres quickly went through multiple printings and expanded editions in 1675, 1676, and 1683. In 1685, as the music industry increasingly elbowed aside theatre, Henry Playford repackaged the volume as The Theatre of Music, a new title that baldly predicated the subsidiary role of the theatre to music. Five years later, Playford would not even bother to associate his published scores with the commercial theatre. His compilation Apollo’s Banquet: Instructions, and Variety of New Tunes, Ayres, Jiggs, and several New Scotch Tunes advertises the “Tunes of the newest French Dances, now used at Court and in Dancing Schools” (1690). The theatre has vanished utterly.