Generalised anxiety disorder is a common disorder in the elderly, with 1–6 month prevalence estimates in the community ranging from 2 to 7%. Reference Schoevers, Beekman, Deeg, Jonker and van Tilburg1–Reference Blazer, George, Hughes, Salzman and Lebowitz3 In primary care, prevalence rates are even higher. Reference de Beurs, Beekman, van Balkom, Deeg, van Dyck and van Tilburg4,Reference Kessler, Zhao, Katz, Kouzis, Frank, Edlund and Leaf5

Unlike other anxiety disorders which have an overwhelmingly early age at onset, the age at onset of generalised anxiety disorder appears to be after 40 years in about a third of individuals, with up to 10% of cases having a first onset after the age of 50. Reference Kessler, Andrade, Bijl, Offord, Demler and Stein6 Generalised anxiety disorder appears to be most common in older age groups, Reference Lieb, Becker and Altamura7 steadily rises until age 50, and may be the most common anxiety disorder in adults aged 55 and over. Reference Beekman, de Beurs, van Balkom, Deeg, van Dyck and van Tilburg8

In younger adults, prospective studies have found that generalised anxiety disorder has notably higher chronicity than major depression, with remission rates at 12 years of approximately 42%. Reference Bruce, Yonkers, Otto, Eisen, Weisberg, Pagano, Shea and Keller9 In older adults it also appears to be chronic, with 6-year remission rates of 31%. Reference Schuurmans, Comijs, Beekman, de Beurs, Deeg, Emmelkamp and van Dyck10

Generalised anxiety disorder in the elderly is frequently comorbid with both major depression (in 30–90% of cases) and with physical illnesses. Reference Beekman, de Beurs, van Balkom, Deeg, van Dyck and van Tilburg8,Reference Flint11 Risk factors for generalised anxiety disorder in the elderly, based on a multivariate analysis in a community-based sample, include increased life stressors or recent losses, increased illness burden and related functional limitations, and absence of social support. Reference Beekman, Bremmer, Deeg, van Balkom, Smit, de Beurs, van Dyck and van Tilburg2

Across all age groups, the presence of generalised anxiety disorder has been found to be associated with a more than 8-fold increase in the annual utilisation of both out-patient medical and psychiatric services. Reference Kessler, Zhao, Katz, Kouzis, Frank, Edlund and Leaf5 In elderly people with the disorder, utilisation of healthcare services continues to be significantly elevated, though relatively few are treated outside primary care settings. Reference de Beurs, Beekman, van Balkom, Deeg, van Dyck and van Tilburg4

In the past 25 years, only one small (n=17 per treatment group) placebo-controlled study has been reported that evaluated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment of DSM–III/IV generalised anxiety disorder in the elderly. Reference Lenze, Mulsant, Shear, Dew, Miller, Pollock, Houck, Tracey and Reynolds12 This study reported significant anxiolytic benefit for citalopram. A second analysis of pooled data (n=195) from five adult generalised anxiety disorder trials found improvement in an elderly subgroup (mean age 65 years) after 8 weeks of treatment with venlafaxine extended release, but the degree of improvement was not significantly better than with placebo. Reference Katz, Reynolds, Alexopoulos and Hackett13 Benzodiazepines continue to be the predominant treatment of generalised anxiety disorder in the elderly, despite the absence of specific evidence for efficacy in this population and the associated risks, including cognitive, memory and psychomotor impairment, and risk of injury due to falling. Reference Madhusoodanan and Bogunovic14

Pregabalin is a novel compound that has been shown to have efficacy in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Reference Montgomery, Tobias, Zornberg, Kasper and Pande15–Reference Feltner, Crockatt, Dubovsky, Cohn, Shrivastava, Targum, Liu-Dumaw, Carter and Pande18

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pregabalin in elderly out-patients diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder.

Method

Study design

This was a randomised (2:1 pregabalin:placebo), double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week parallel group comparison following a 1-week drug-free screening period. At study end, treatment was discontinued during a double-blind, 1–5 day taper, with a final follow-up visit at 1 week.

Pregabalin treatment was initiated at 50 mg/day, followed by an increase to 100 mg/day on day 3, and 150 mg/day on day 5. Dosing was flexible from weeks 1 to 6 in the range of 150–600 mg/day, administered either twice daily or three times daily. Patients were maintained on the same dose of medication from weeks 6 to 8.

The study was conducted at 13 US and 69 European centres in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. 19 The protocol was approved at each centre by the appropriate ethics panel, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrolment. Patients were recruited through clinic referrals and by ethics panel-approved advertisements in local media.

Participant selection

Male or female out-patients aged 65 years or older, who met DSM–IV 20 criteria for generalised anxiety disorder based on a structured Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar21,Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar22 who had screening and baseline Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HRSA) Reference Hamilton23 scores ⩾20 and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ⩾24, were eligible for entry. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

(a) current or past DSM–IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, psychotic, or bipolar disorder

-

(b) current DSM–IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder (generalised type), panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder or acute stress disorder, borderline or antisocial personality disorder, eating disorder, delirium, dementia, amnestic disorder, alcohol or substance dependence and/or misuse (in the past 6 months)

-

(c) positive urine drug screen

-

(d) any clinically significant acute or unstable medical condition (including current seizure disorder, even if stable on treatment) or clinically significant electrocardiogram (ECG) or laboratory abnormalities

-

(e) alanine/aspartate aminotransferase levels >3 times the upper limit of normal or creatinine clearance rates ⩽45 ml/min

-

(f) concurrent psychotherapy for generalised anxiety disorder, unless in stable treatment for >3 months

-

(g) concomitant treatment with psychotropic medication during the study and for at least 2 weeks prior to the screening visit (5 weeks for fluoxetine)

-

(h) current suicide risk, based on the clinical judgement of the investigator

-

(i) depressive symptoms predominating over anxiety symptoms.

Medical evaluation, physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), laboratory data and pregnancy test were carried out at screening.

Efficacy measures

The primary efficacy measure was the change from baseline to end-point (week 8 or last observation carried forward (LOCF) in double-blind phase) in the 14-item, clinician-rated HRSA. The HRSA was performed at screening, baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 (or at the time of early discontinuation), and at week 9 (the post-taper follow-up visit). The original HRSA has shown acceptable internal consistency and construct validity in elderly people with generalised anxiety disorder. Reference Bech, Stanley and Zebb24

Secondary efficacy measures were:

-

(a) 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD–17), Reference Hamilton25 completed at baseline and week 8 (or early termination)

-

(b) the Clinical Global Impression – Improvement Scale (CGI–I), Reference Guy26 completed at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 (or early termination)

-

(c) the Symptom Checklist–90, revised (SCL–90–R), Reference Bech, Allerup, Maier, Albus, Lavori and Ayuso27 completed at baseline and week 8 (or early termination)

-

(d) the MMSE, completed at baseline, week 8 (or early termination), and at the week 9 post-taper visit.

The following derived outcomes were also analysed:

-

(a) HRSA psychic anxiety factor (items 1–6, 14)

-

(b) HRSA somatic anxiety factor (items 7–13)

-

(c) individual HRSA anxiety (item 1) and tension (item 2) items

-

(d) the SCL–90–R anxiety sub-scale (consisting of 8 items)

-

(e) responder criteria (defined as CGI–I ⩽2 ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved, and ⩾50% reduction from baseline in the HRSA total score)

-

(f) HRSA remission criteria (HRSA ⩽7). A repeated-measures analysis was also performed on the HRSA and CGI–I scales.

Experienced raters were used and rater training was provided. Linguistically validated versions of efficacy measures were administered in the native language of the study patient.

Safety and tolerability measures

Spontaneously reported or observed adverse events were recorded with regard to onset, duration and severity. Adherence was monitored by counts of returned medication, and patients were counselled if they were found to be non-adherent. Vital signs were obtained at each visit. The ECG, physical examination, and laboratory testing were repeated at week 8 (or early termination).

Statistical methods

As preferred by regulatory bodies, the primary efficacy analysis, which compared the HRSA change scores at end-point, was carried out at end-point on the intent-to-treat population (all randomised patients who received at least one dose of study medication) using the LOCF for missing values. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical package (Version 8) for Windows. A sample size of 261 evaluable patients per treatment group would provide 80% power to detect a mean difference of 3.0 with a standard deviation of 8.1 in the HRSA score between placebo and pregabalin with an experiment-wise α-level of 0.05. The HRSA change score was also analysed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model that included the effects of treatment and centre, with baseline HRSA total score as a covariate. Reference Neter, Wasserman and Kutner28 Least-squares means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Weekly HRSA change scores were analysed separately at each week by ANCOVA using a model that included the effects of treatment and centre, with baseline HRSA total score as a covariate.

The treatment effects of pregabalin on the HRSA psychic and somatic sub-scales, and on HRSA items 1 and 2, were evaluated by ANCOVA analyses. The HRSD change scores were analysed using ANCOVA with treatment and centre in the model, and HRSD score at baseline as the covariate (α=0.05, two-sided).

Logistic regression adjusting for centre was performed to compare the percentage of HRSA responders/remitters by treatment group in the intent-to-treat population (α=0.05, two-sided). Reference Hosmer and Lemeshow29,Reference Stokes, Davis and Koch30 Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for pregabalin relative to placebo were computed. The CGI–I responder rates were analysed in the same manner as the HRSA responder rates.

A secondary post hoc mixed-model repeated-measures analysis, which is increasingly recommended as an alternative method to assess the impact of missing data, was carried out. No adjustment for multiple comparisons of the secondary measures was made as these are usually regarded as exploratory.

Results

Participant characteristics and disposition

Of the 366 patients screened, 273 were randomised and received study treatment (Fig. 1). There were no significant between-group differences in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics (Table 1). A similar proportion of participants in the pregabalin and placebo groups (75.1% v. 71.9%) completed double-blind study treatment (Fig. 1). Reasons for premature discontinuation were approximately similar in both treatment groups.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of participants through study. DB, double-blind; ITT, intent-to-treat. a. Did not enter taper phase because of dosing error (n=1), non-adherence (n=1), and administrative reasons (n=2). b. Patients who did not complete the 8 weeks of double-blind treatment could nevertheless enter taper phase.

Table 1 Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of patient sample

| Pregabalin n=177 | Placebo n=96 | |

|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 79 | 75 |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (s.d.) | 72.4 (5.6) | 72.2 (6.4) |

| ⩾75 years, % | 35 | 32 |

| White, % | 98 | 99 |

| Weight, kg: mean (s.d.) | 70.7 (12.2) | 74.4 (17.2) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder history | ||

| Estimated age at onset, years: mean (s.d.) | 56 (17) | 56 (17) |

| Estimated number of prior episodes, mean (s.d.) | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.9) |

| Duration of current episode, months: mean (s.d.) | 16 (30) | 14 (25) |

| Previous psychiatric diagnoses, % | ||

| Major depression | 11.3 | 12.5 |

| Dysthymic disorder or depression NOS | 12.4 | 9.4 |

| Other anxiety disorder | 1.7 | 4.2 |

| HRSA, mean (s.d.) | ||

| Total score | 27 (4.8) | 26 (4.1) |

| Psychic factor score | 14.3 (2.9) | 14.2 (2.4) |

| Somatic factor score | 12.3 (3.1) | 11.9 (3.1) |

| HRSD–17, mean (s.d.) | 14 (3.7) | 14 (3.5) |

| MMSE, mean (s.e.) | 28.3 (0.1) | 28.3 (0.2) |

HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HRSD–17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NOS, not otherwise specified

Efficacy

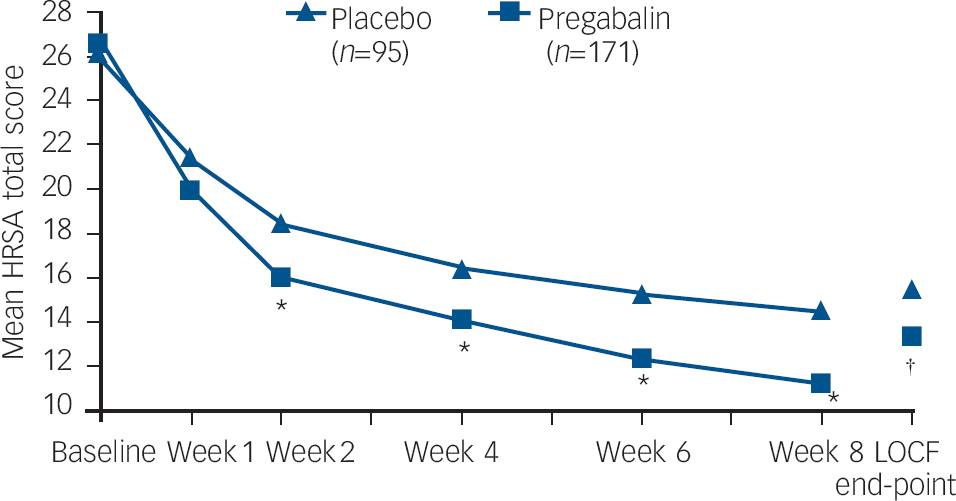

On the primary outcome, change from baseline to end-point LOCF in HRSA total score, treatment with pregabalin was significantly superior to placebo: pregabalin −12.8 (s.d.=0.7); placebo −10.7 (s.d.=0.9); P=0.044. Additionally, from week 2 through the end of double-blind treatment, pregabalin showed statistically significant greater changes in HRSA score compared with placebo patients (Fig. 2 and Table 2; a more detailed version of Table 2, showing results from baseline to end-point, appears as online Table DS1).

Fig. 2 Mean HRSA total score over 8 weeks of study treatment. HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; LOCF end-point, last-observation carried forward ANCOVA model. Weeks 1–8 P-values based on a repeated-measures mixed-effect model. * P<0.01; P=0.0437.

Table 2 Efficacy variables: results of repeated measures and LOCF end-point analyses

| Pregabalin | Placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy variables | n | LS mean change (s.e.) | n | LS mean change (s.e.) | P a | ||

| HRSA total score | |||||||

| Week 8 | 120 | –14.4 (0.6) | 62 | –11.6 (0.8) | 0.0070 | ||

| LOCF end-point | 171 | –12.8 (0.7) | 95 | –10.7 (0.9) | 0.0437 | ||

| HRSA psychic factor | |||||||

| Week 8 | 120 | –7.8 (0.4) | 62 | –6.3 (0.5) | 0.0111 | ||

| LOCF end-point | 171 | –7.0 (0.4) | 95 | –5.6 (0.5) | 0.0242 | ||

| HRSA somatic factor | |||||||

| Week 8 | 120 | –6.6 (0.3) | 62 | –5.4 (0.5) | 0.0248 | ||

| LOCF end-point | 171 | –5.9 (0.3) | 95 | –5.0 (0.4) | 0.0956 | ||

| CGI–I | |||||||

| Week 8 | 121 | 2.3 (0.1) | 62 | 2.7 (0.1) | 0.0075 | ||

| LOCF end-point | 171 | 2.5 (0.1) | 95 | 2.8 (0.1) | 0.0382 | ||

CGI–I, Clinical Global Impression – Improvement Scale. HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; LOCF, last observation carried forward; LS mean, least-squares mean

a. Nominal P-values are shown for secondary efficacy measures, unadjusted for multiplicity

There was a significant advantage for pregabalin compared with placebo from week 2 onwards on the HRSA psychic anxiety factor and from week 4 onwards on the HRSA somatic anxiety factor (Fig. 3 and Table DS1). There was a significantly greater improvement on the CGI–I with pregabalin compared with placebo (Table DS1).

Fig. 3 Mean change in HRSA psychic and somatic factor scores: results of mixed-model repeated-measures analysis. HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01.

There were significantly more responders (HRSA ⩾50% reduction from baseline) on pregabalin compared with placebo at week 4 but not at week 8 on either a completer or LOCF analysis (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference at end-point in responders on the CGI–I (‘much’/‘very much improved’: 58.4% v. 48.4%; P=0.117). There was no significant difference in remission rates (HRSA ⩽7: 29.8% v. 24.2%; P=0.368).

Fig. 4 Mean HRSA responder rates at 4 weeks and 8 weeks. HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; OC, observed case; LOCF, last observation carried forward. * P<0.05; P⩽0.07.

An ANCOVA of patient-rated anxiety was consistent with the investigator-rated HRSA: there was significantly greater improvement on the SCL–90–R anxiety sub-scale least-squares mean change score at end-point for pregabalin compared with placebo (–5.6 (s.d.=0.4) v. −4.2 (s.d.=0.5); P=0.0412). There was no difference in end-point change on the SCL–90–R total score with pregabalin compared with placebo (–29.7 (s.d.=2.7) v. −27.9 (s.d.=3.5); P=0.6574).

An ANCOVA of secondary baseline depressive symptoms (mean HRSD–17=14 (s.d.=3.6) found significantly greater improvement at end-point for pregabalin compared with placebo (–5.5 (s.d.=0.5) v. −4.0 (s.d.=0.6); P=0.0414).

Efficacy in clinically relevant subgroups

To address the regulatory request for information on efficacy in patients with more severe generalised anxiety disorder, a post hoc analysis was carried out in the subgroup of participants with high anxiety severity, defined as a baseline HRSA total score ⩾26. The magnitude of improvement (least-squares mean change score at 8-week end-point) was numerically greater for pregabalin compared with placebo (–15.4 (s.e.=1.0) v. −12.7 (s.e.=1.4); P<0.096). A comparison of effect sizes (pregabalin v. placebo at end-point) showed comparable benefit as the severity of baseline HRSA total scores increased from HRSA ⩾20 (Cohen's d=0.26), to ⩾22 (d=0.28), to ⩾24 (d=0.32), to ⩾26 (d=0.30), to ⩾28 (d=0.33).

The influence of baseline severity of depressive symptoms was also examined. The magnitude of end-point improvement in the HRSA total score for pregabalin was similar in participants with high v. low levels of subsyndromal depression at baseline (HRSD ⩾15 v. HRSD<15: −12.5 (s.d.=1.1) v. −13.0 (s.d.=0.9)), a finding mirrored in those on placebo (–11.0 (s.d.=1.4) v. −10.3 (s.d.=1.2)).

Tolerability and safety

Pregabalin was well-tolerated on a mean maximal dose of 270 mg/day (s.d.=145). The great majority of adverse events were mild to moderate in intensity and transient, with tolerance typically developing within the first 1–3 weeks of treatment (Table 3). Discontinuations due to adverse events were similar for pregabalin and placebo (10.7% v. 9.4%). The mean change in weight at end-point was slightly higher for pregabalin (+0.8 kg (s.d.=2.5)) compared with placebo (–0.2 kg (s.d.=2.5)).

Table 3 Treatment-emergent adverse events (all causes, with pregabalin incidence ≥5%)

| Pregabalin, n=177 | Placebo, n=96 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | Total incidence (severe), % | Onset, a day | Duration, a days | Total incidence (severe), % | Onset, a day | Duration, a days | ||||

| Dizziness | 20.3 (1.1) | 5.5 | 8 | 11.5 (0) | 10 | 6 | ||||

| Somnolence | 13.0 (0) | 4 | 16 | 7.3 (0) | 5 | 14 | ||||

| Headache | 10.2 (0) | 10 | 3.5 | 8.3 (2.1) | 22.5 | 3 | ||||

| Nausea | 9.0 (0.6) | 26.5 | 6 | 6.3 (1.0) | 9 | 7 | ||||

| Infection | 5.6 (0) | 24.5 | 10 | 3.1 (0) | 7 | 7 | ||||

a. Reported as median days

Serious adverse events occurred in nine patients during study treatment, three (3.1%) on placebo and seven (4.0%) on pregabalin (two serious events occurred in one patient on pregabalin: an ulcer of the toe, and progression of chronic arteritis). One death due to cerebral haemorrhage occurred in an 82-year-old woman (this was judged by the investigator as not related to pregabalin). Three of the serious adverse events in patients on pregabalin were judged by the investigator to be related to pregabalin: increased anxiety, somnolence, and a fractured arm secondary to a fall. There was no difference in the incidence of treatment-emergent changes in ECG or laboratory tests for pregabalin compared with placebo.

During rapid taper, the incidence of discontinuation-emergent adverse events was very low for pregabalin and placebo, respectively: dizziness 0.6% v. 0%; insomnia 0.6% v. 0%; pruritus 0% v. 1.0%; and peripheral oedema 0% v. 1.0%.

Discussion

The results of the protocolled intent-to-treat LOCF analysis demonstrate that pregabalin is effective in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder in adults aged 65 and older. Pregabalin treatment was associated with significant improvement on the HRSA total score from week 2 through to end-point. About 50% of patients on pregabalin met HRSA responder criteria at week 4, which increased to 64% by week 8, although only the week-4 response rate was significant compared with placebo.

Treatment with pregabalin resulted in significant improvement in both psychic and somatic symptoms of anxiety. The broad-spectrum improvement in both psychic and somatic symptoms is consistent with data from studies in younger adults and contrasts with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor anxiolytics, which do not always reduce somatic anxiety symptoms.

Patients in the current study reported a relatively late first onset of generalised anxiety disorder, at a mean age of 56 years. Although this is consistent with emerging epidemiological data, Reference Kessler, Andrade, Bijl, Offord, Demler and Stein6 which suggest that generalised anxiety disorder may frequently begin after age 50, the reliability of retrospective assessment of age at onset is uncertain. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether early- v. late-onset generalised anxiety disorder have different presentations or a different course of illness or treatment response.

In the current sample, approximately 50% of participants presented with severe anxiety, defined as a minimum HRSA score of 26 at baseline. Treatment with pregabalin was comparably effective regardless of baseline anxiety severity, with effect sizes that showed a marginal increase (from 0.26 to 0.33) as baseline anxiety severity increased. Similarly, pregabalin was equally effective in the subgroup (∼40%) of patients who reported higher baseline levels of depressive symptoms (HRSD ⩾15).

The end-point difference in the HRSA total score (<3 points) is in line with the difference from placebo reported with other recently licensed treatments for generalised anxiety disorder, such as escitalopram and venlafaxine. Reference Stein, Andersen and Goodman31 Although these differences might appear modest, they are clinically relevant and have been used to justify the licensing of treatments for generalised anxiety disorder. This is the first large, placebo-controlled pharmacological treatment study in elderly people with generalised anxiety disorder and it is reassuring to have convincing evidence of the efficacy of a treatment for adults of all ages.

Pregabalin was well-tolerated at a mean dose of 270 mg/day (s.d.=145). The proportion of patients who discontinued because of poor tolerability was similar for pregabalin and placebo (∼10%). Severe adverse events for pregabalin were rare, occurring with a frequency above 1% only for dizziness (2.1%). Tolerance rapidly developed to most adverse events, with a median duration in the range of 4–16 days. No unexpected safety events were noted on ECG or laboratory tests. During rapid taper, the incidence of discontinuation-emergent adverse events was the same for pregabalin and placebo.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Study entry criteria excluded patients with comorbid major depression and/or other Axis I anxiety disorders, which reduces the generalisability of the results to clinical practice, where such comorbidity is relatively common. Future research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of pregabalin monotherapy in generalised anxiety disorder presenting with comorbid affective and anxiety disorders. The exclusion of more severe medical illness and psychiatric comorbidity is required in all pivotal studies seeking evidence for a licence for treatment in generalised anxiety disorder in order that the therapeutic benefit observed may be attributable to the effect on generalised anxiety disorder alone. However, the exclusion of patients with comorbid conditions is a limitation and future research is needed to establish the safety of pregabalin in elderly patients with more severe medical comorbidity. In light of the chronicity of generalised anxiety disorder, the current study is limited by the relatively short duration. A final limitation is the use of nominal P-values, unadjusted for multiple comparisons, for secondary efficacy measures. However, the study was designed for the analysis of the primary efficacy measure; the secondary analyses are usually regarded as exploratory. We consider the consistency of the findings with the secondary measures to be reassuring in supporting the efficacy demonstrated with the primary measure.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that pregabalin, in a dosing range of 150–600 mg/day, is a safe and effective treatment of generalised anxiety disorder in the elderly regardless of generalised anxiety disorder severity or level of sub-syndromal depression. The anxiolytic efficacy of pregabalin had an early onset (by 2 weeks) and significantly improved both psychic and somatic symptoms of anxiety.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.