Introduction

It was long thought that women with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) had a more favourable course compared to male patients, but that idea should be reconsidered. Female patients have the same number of readmissions during their lifetime (Ceskova, Prikryl, Libiger, Svancara, & Jarkovsky, Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Libiger, Svancara and Jarkovsky2015; Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen, & Taipale, Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020), have similar recovery rates (12.9% for women and 12.1% for men) (Jaaskelainen et al., Reference Jaaskelainen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha, Isohanni and Miettunen2013) and similar functional outcomes 10 years after a first psychotic episode (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, de la Foz, Setién-Suero, Ramírez-Bonilla, Suárez-Pinilla, Son and Crespo-Facorro2020; Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Kebede, Fekadu, Medhin, Hanlon, Alem and Shibre2020). Although male patients experience more negative symptoms, females have more affective symptoms (Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad, & Kulkarni, Reference Ochoa, Usall, Cobo, Labad and Kulkarni2012). Aggression towards others is more common in males, whereas self-harm and suicide attempts are more common among female patients (Dama et al., Reference Dama, Veru, Schmitz, Shah, Iyer, Joober and Malla2019; Dubreucq et al., Reference Dubreucq, Plasse, Gabayet, Blanc, Chereau, Cervello and Dubreucq2021; Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride, & Jones, Reference Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride and Jones2019; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020). Although the later age of onset and lower comorbidity with substance abuse in women may lead to better functioning in the early stages of the illness (Usall, Ochoa, Araya, & Márquez, Reference Usall, Ochoa, Araya and Márquez2003), this benefit is not maintained in the more chronic phase and advantages for women even seem to reverse after the age of 50 (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Kebede, Fekadu, Medhin, Hanlon, Alem and Shibre2020; Shlomi Polachek et al., Reference Shlomi Polachek, Manor, Baumfeld, Bagadia, Polachek, Strous and Dolev2017; Thorup, Waltoft, Pedersen, Mortensen, & Nordentoft, Reference Thorup, Waltoft, Pedersen, Mortensen and Nordentoft2007). Hence, the idea that women have a better overall course of SSD compared to men is not correct. However, the vast majority of the literature and guidelines on antipsychotic treatment neglects differences between male and female patients and base their conclusions on studies with predominantly male participants (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019; Lally & MacCabe, Reference Lally and MacCabe2015; Lange, Mueller, Leweke, & Bumb, Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017; Phillips & Hamberg, Reference Phillips and Hamberg2016; Santos-Casado & García-Avello, Reference Santos-Casado and García-Avello2019; Zakiniaeiz, Cosgrove, Potenza, & Mazure, Reference Zakiniaeiz, Cosgrove, Potenza and Mazure2016).

Psychosocial differences in diet, smoking and substance abuse between men and women (i.e. gender differences), can influence the efficacy and tolerability of antipsychotics (Seeman, Reference Seeman2004). In addition, biologically determined differences (i.e. sex differences), such as body composition and hormonal transitions affect the drug pharmacokinetics, determined by the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion, and drug pharmacodynamics which involves receptor binding, receptor sensitivity and the receptor binding profile of a drug (Iversen et al., Reference Iversen, Steen, Dieset, Hope, Mørch, Gardsjord and Jönsson2018; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017; Zucker & Prendergast, Reference Zucker and Prendergast2020). The female sex hormones in general, and oestrogens in particular play a major role in these sex differences (Brand, de Boer, & Sommer, Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021; González-Rodríguez & Seeman, Reference González-Rodríguez and Seeman2019). However, current guidelines on the prescription of antipsychotics do not take these differences in account (Keepers et al., Reference Keepers, Fochtmann, Anzia, Benjamin, Lyness, Mojtabai and Hong2020; Ventriglio et al., Reference Ventriglio, Ricci, Magnifico, Chumakov, Torales, Watson and Bellomo2020). This review serves as a comprehensive overview of currently available literature on the differences in the action of antipsychotic medication in female v. male patients with SSD, with special considerations for female-specific pharmacotherapy regimens during different (hormonal) stages of life (i.e. menarche, pregnancy, lactation and menopause).

Gender differences in prescription

Although some patients prefer to be treated without medication, most psychotic episodes require pharmacological treatment with antipsychotics. Although classical antipsychotics such as haloperidol are still being used as second generation and other newer antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine, amisulpride and quetiapine are often preferred by psychiatrists given their better efficacy–tolerability balance (Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Fleischhacker, Boter, Davidson, Vergouwe, Keet and Grobbee2008). Clozapine is usually provided as a second or third line of treatment, when two other antipsychotics did not yield remission from psychosis. Although clozapine is superior in efficacy for these individuals, it does have some bothersome side-effects, such as being diabetogenic, inducing weight gain, severe constipation and (rarely) agranulocytosis (Nielsen, Damkier, Lublin, & Taylor, Reference Nielsen, Damkier, Lublin and Taylor2011).

Although no sex-specific guidelines currently exist for prescribing antipsychotics, notable differences are observed in prescription patterns between men and women, caused by preferences of both the physician and the patient. Women may experience some side-effects as more severe than men and may, for example, encounter more difficulties with antipsychotic-induced weight gain (Achtyes et al., Reference Achtyes, Simmons, Skabeev, Levy, Jiang, Marcy and Weiden2018; Connors & Casey, Reference Connors and Casey2006). The risk of weight gain is, in particular, of great influence in the decision to take medication in women, causing non-adherence to prescribed medications specifically in this gender (Achtyes et al., Reference Achtyes, Simmons, Skabeev, Levy, Jiang, Marcy and Weiden2018; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Conus, Eide, Mass, Karow, Moritz and Naber2004).

Based on a Finnish nation-wide cohort study, women are more often prescribed quetiapine and aripiprazole, whereas men are more often prescribed clozapine and olanzapine (Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020). Also, the use of additional psychotropic medication (e.g. antidepressants, mood stabilisers and benzodiazepines) is more common in women compared to in men (Ceskova & Prikryl, Reference Ceskova and Prikryl2012; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020). In the USA and European countries, prescription rates of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are lower in women (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Strakowski, Schwiers, Amicone, Fleck, Corey and Farrow2004; Mahadun & Marshall, Reference Mahadun and Marshall2008; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Montgomery and Marder2007; Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020), although the compliance to medication is similar in men and women (Caqueo-Urízar, Fond, Urzúa, & Boyer, Reference Caqueo-Urízar, Fond, Urzúa and Boyer2018; Castberg, Westin, & Spigset, Reference Castberg, Westin and Spigset2009; Leijala, Kampman, Suvisaari, & Eskelinen, Reference Leijala, Kampman, Suvisaari and Eskelinen2021).

Sex differences in the pharmacokinetics of antipsychotics

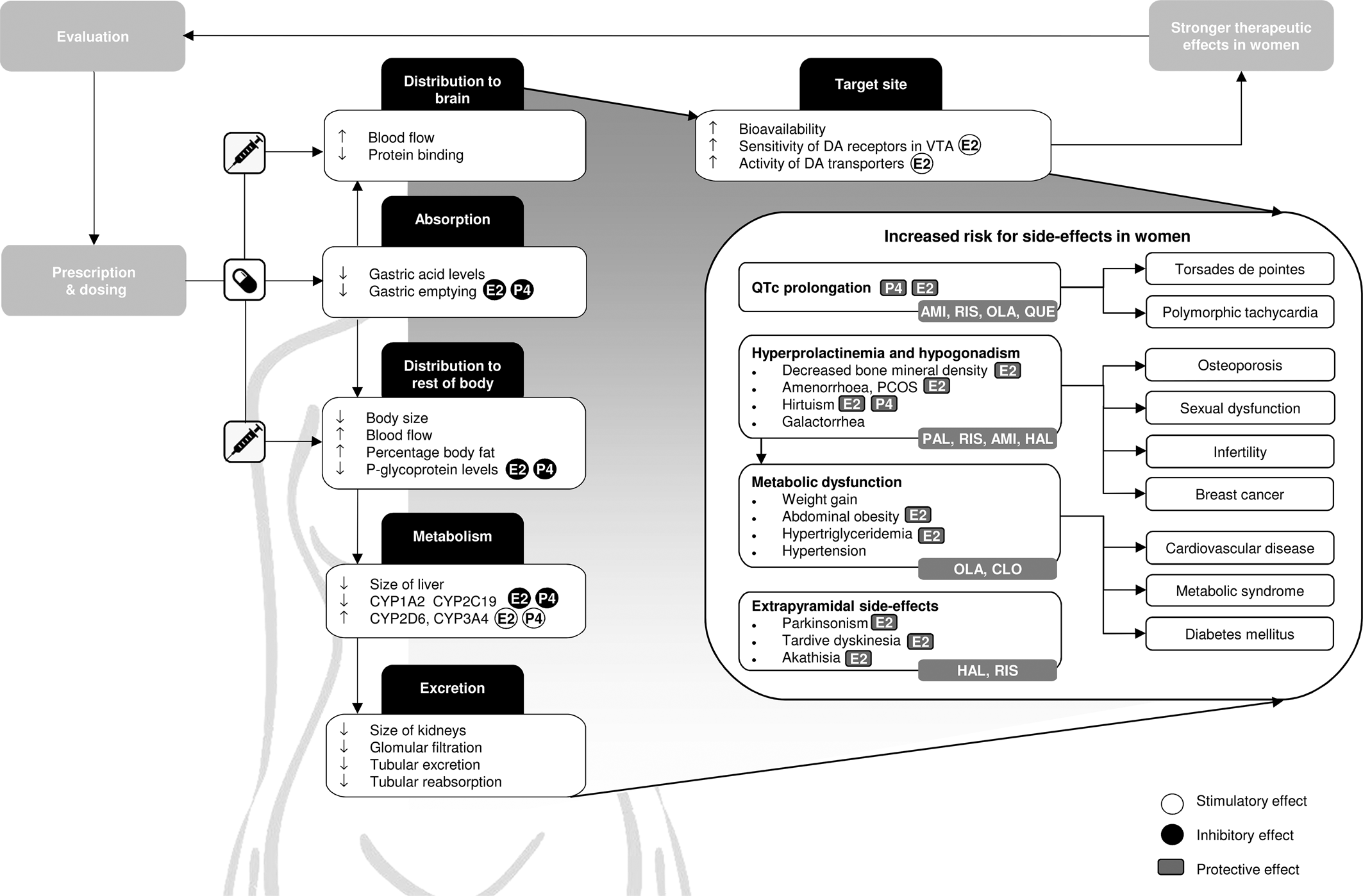

Body composition differs significantly between the sexes: women have smaller organs, more fatty tissue and less muscle tissue, which changes the volume of distribution, especially for lipophilic drugs (Seeman, Reference Seeman2018). In addition, women have some 10–15% greater blood flow to the brain, which makes it easier for a drug to reach their target receptor (Fig. 1) (Gur & Gur, Reference Gur and Gur1990). Castberg, Westin, Skogvoll, and Spigset (Reference Castberg, Westin, Skogvoll and Spigset2017) included 43 079 blood samples of patients between 18 and 100 years old using olanzapine, risperidone or quetiapine and concluded that women generally have 20–30% higher dose-adjusted concentrations, which is a proxy for bioavailability, compared to men. Another study, including 26 388 patients of all ages, reported higher dose-adjusted concentrations in women for 11 out of 12 antipsychotics (Jönsson, Spigset, & Reis, Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019), with the largest differences for olanzapine and clozapine (59.0% and 40.4% higher in women, respectively), whereas for quetiapine, dose-adjusted concentrations were 6.4% lower in women. Similarly, Eugene and Masiak (Reference Eugene and Masiak2017) reported dopamine receptor occupancy rates of 70% for male and female patients (mean age: 25.6 ± 7.9 for men; 28.9 ± 9.1 for women), whereas men were taking a higher dose (20 v. 10 mg/day). Since women are often treated with multiple psychotropic medications (Sommer et al., Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale2020), drug interactions are especially relevant for this sex and become even more crucial when women are overmedicated. For example, clinically relevant effects on serum levels of several antipsychotics have been reported for the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine (Spina & De Leon, Reference Spina and De Leon2014). In addition, sex differences in the pharmacokinetics of antidepressants should be taken into account in women with SSD who are also being treated for depression, which are discussed in detail in a review by Damoiseaux, Proost, Jiawan, and Melgert (Reference Damoiseaux, Proost, Jiawan and Melgert2014).

Fig. 1. Graphical overview of relevant differences in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and therapeutic effects of antipsychotics in women compared to men. Side-effects that should be obtaining additional attention in women are defined, together with commonly used antipsychotics that carry the highest risks for these side-effects. In addition, the stimulatory and inhibitory effects of oestradiol (E2), which is the predominant form of oestrogen, and progesterone (P4) on pharmacokinetic processes are shown, as well as the protective effects of E2 and P4 on specific side-effects. CYP, cytochrome P450; AMI, amisulpride; CLO, clozapine; HAL, haloperidol; OLA, olanzapine; PAL, paliperidone; QUE, quetiapine; RIS, risperidone; E2, oestradiol; P4, progesterone; DA, dopamine; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Absorption and distribution

When administered orally, the absorption of a drug largely depends on gut physiology. Female sex hormones reduce gastric emptying and intestinal motility (Freire, Basit, Choudhary, Piong, & Merchant, Reference Freire, Basit, Choudhary, Piong and Merchant2011), resulting in lower gastrointestinal transit rates in women (Hutson, Roehrkasse, & Wald, Reference Hutson, Roehrkasse and Wald1989; Jiang, Greenwood-Van Meerveld, Johnson, & Travagli, Reference Jiang, Greenwood-Van Meerveld, Johnson and Travagli2019). This enhances drug absorption and increases the bioavailability of oral antipsychotics (Stillhart et al., Reference Stillhart, Vučićević, Augustijns, Basit, Batchelor, Flanagan and Müllertz2020). After menopause, transit rates increase to a level similar to that of age-matched men (Camilleri, Reference Camilleri2020; Gonzalez, Loganathan, Sarosiek, & McCallum, Reference Gonzalez, Loganathan, Sarosiek and McCallum2020).

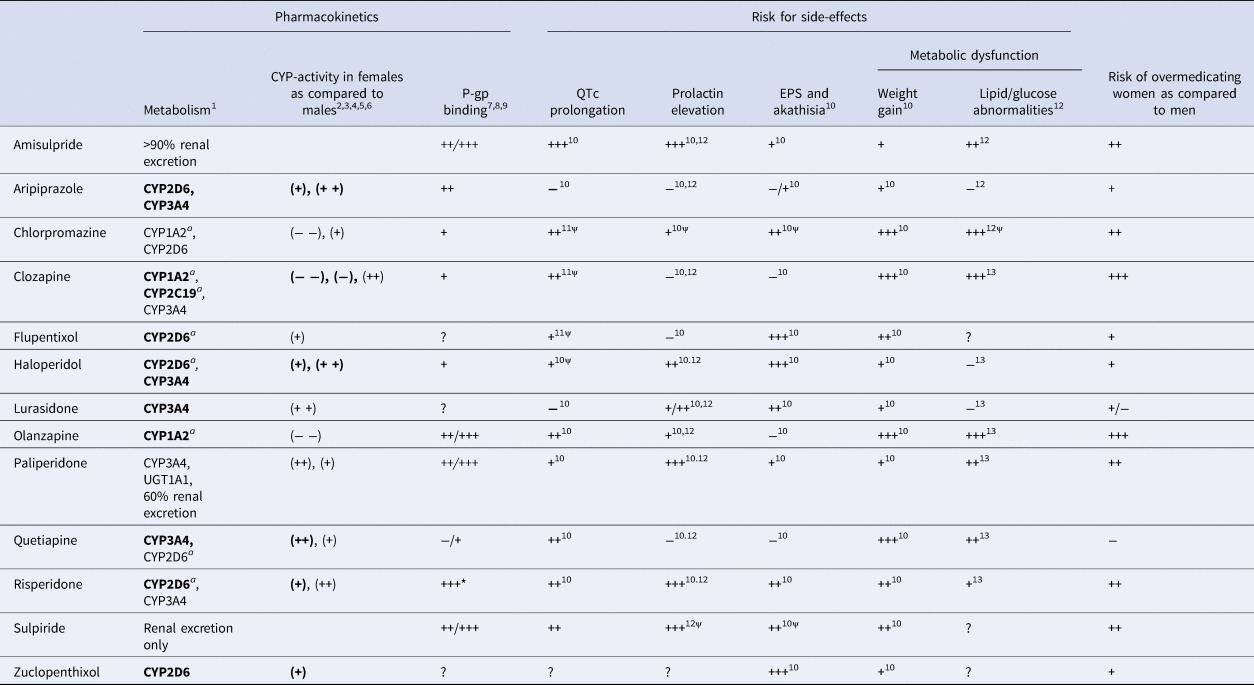

The absorption and distribution of antipsychotic drugs is influenced by P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an efflux transporter that is located on the cell membrane that limits the systemic exposure of its substrates (Elmeliegy, Vourvahis, Guo, & Wang, Reference Elmeliegy, Vourvahis, Guo and Wang2020). P-gp levels are some two-fold lower in women compared to that in men, being decreased by oestrogens and progesterone (Bebawy & Chetty, Reference Bebawy and Chetty2009; Nicolas, Espie, & Molimard, Reference Nicolas, Espie and Molimard2009). Although lower P-gp levels thus enable a drug to enter the brain more easily, non-target organs also become more accessible for the drug, potentially causing more side-effects (Fig. 1) (Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018). Sex differences in bioavailability of antipsychotics are expected to be more pronounced for drugs that bind P-gp more tightly (e.g. risperidone and aripiprazole) (Table 1) (Bebawy & Chetty, Reference Bebawy and Chetty2009; Doran et al., Reference Doran, Obach, Smith, Hosea, Becker, Callegari and Zhang2005; Linnet & Ejsing, Reference Linnet and Ejsing2008; Moons, De Roo, Claes, & Dom, Reference Moons, De Roo, Claes and Dom2011; Nagasaka, Oda, Iwatsubo, Kawamura, & Usui, Reference Nagasaka, Oda, Iwatsubo, Kawamura and Usui2012).

Table 1. Summary of drug-specific pharmacokinetic properties, side-effects and overdosing risks in women

CYP, cytochrome P450; EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; UGT, UDP glucuronosyl transferase.

The risk of overmedicating women as compared to men is estimated based on drug-specific metabolism, P-gp binding and CYP-activity in women compared to men. In addition, the risk of QTc prolongation, prolactin elevation, EPS and akathisia, weight gain and lipid/glucose abnormalities are also defined.

1, Hiemke et al. (Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018); 2, Scandlyn et al. (Reference Scandlyn, Stuart and Rosengren2008); 3, Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Koh and Jeong2013); 4, Piccinato et al. (Reference Piccinato, Neme, Torres, Silvério, Pazzini, Rosa e Silva and Ferriani2017); 5, Hagg et al. (Reference Hagg, Spigset and Dahlqvist2001); 6, Tamminga et al. (Reference Tamminga, Wemer, Oosterhuis, Wieling, Wilffert, de Leij and Jonkman1999); 7, Doran et al. (Reference Doran, Obach, Smith, Hosea, Becker, Callegari and Zhang2005); 8, Linnet & Ejsing (Reference Linnet and Ejsing2008); 9, Nagasaka et al. (Reference Nagasaka, Oda, Iwatsubo, Kawamura and Usui2012); 10, Huhn et al. (Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019); 11, Wenzel-Seifert et al. (Reference Wenzel-Seifert, Wittmann and Haen2011); 12, Peuskens et al. (Reference Peuskens, Pani, Detraux and De Hert2014); 13, De Hert et al. (Reference De Hert, Detraux, van Winkel, Yu and Correll2012).

(++), activity strongly higher in females; (+), activity higher in females; only of relevance during pregnancy; (−), activity lower in females; (− −), activity strongly lower in females; a, inhibited by oral oestrogenic contraceptives; +++, high incidence/high severity/strong; ++, moderate incidence/moderate severity/moderate; +, light incidence/mild severity/mild; −, low/very low/small; ?, unknown; *, main metabolite of risperidone 9-OH-risperidone. ψ, level of evidence is limited. When enzymes are indicated in bold, drug plasma concentrations will significantly increase or decrease when combined with strong to moderate inducers or inhibitors (see Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018).

Women naturally have more subcutaneous fat compared to men and this slows the absorption and perfusion of LAI antipsychotics (Soldin, Chung, & Mattison, Reference Soldin, Chung and Mattison2011; Yonkers, Kando, Cole, & Blumenthal, Reference Yonkers, Kando, Cole and Blumenthal1992). The accumulation of LAI antipsychotics in adipose tissue increases their half-life time, resulting in extended release to the blood (Soldin et al., Reference Soldin, Chung and Mattison2011; Yonkers et al., Reference Yonkers, Kando, Cole and Blumenthal1992). Short dosing intervals could lead to higher serum concentrations over time (Seeman, Reference Seeman2020). Female patients may, thus, benefit from longer dosage intervals for LAI compared to males.

Metabolism

Drug metabolism is generally lower in the female sex, as women have a smaller liver and differential functioning of the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) system compared to men (Soldin et al., Reference Soldin, Chung and Mattison2011). Most antipsychotics are metabolised by CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and/or CYP3A4 (Table 1) (Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018; Ravyn, Ravyn, Lowney, & Nasrallah, Reference Ravyn, Ravyn, Lowney and Nasrallah2013). Of note, fluvoxamine has an inhibitory effect on all CYP enzymes, especially on CYP1A2 and CYP2C19, whereas paroxetine and fluoxetine are both potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 metabolism. Co-medication with these SSRIs may, thus, require downward dosage adjustments (Spina & De Leon, Reference Spina and De Leon2014).

CYP1A2

CYP1A2 activity is lower in females compared to that in males (Scandlyn, Stuart, & Rosengren, Reference Scandlyn, Stuart and Rosengren2008). Clozapine and olanzapine are both mainly metabolised by this enzyme and with similar dosing, these antipsychotics reach 25–60% higher dose-adjusted concentrations in women (Bigos et al., Reference Bigos, Pollock, Coley, Miller, Marder, Aravagiri and Bies2008; Castberg et al., Reference Castberg, Westin, Skogvoll and Spigset2017; Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Mao, Li, Li, Chen, Jiang and Mitchell2007). Since both oestrogen and progesterone are substrates of CYP1A2, they have an inhibitory effect on this enzyme (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Shang, Zhong, Xu, Shi and Wang2020). Drug plasma concentrations are, therefore, specifically higher in the female sex when hormone levels are high (e.g. before menopause) whereas they decrease in relative terms when hormone levels fall (e.g. after menopause) (Soldin et al., Reference Soldin, Chung and Mattison2011).

CYP3A4

In contrast to CYP1A2, CYP3A4 activity is about 20–30% higher in premenopausal women as compared to the other sex (Greenblatt & von Moltke, Reference Greenblatt and von Moltke2008; Scandlyn et al., Reference Scandlyn, Stuart and Rosengren2008; Wolbold, Reference Wolbold2003; Yang & Li, Reference Yang and Li2012) and its activity is stimulated by oestrogens and progesterone (Choi, Koh, & Jeong, Reference Choi, Koh and Jeong2013; Piccinato et al., Reference Piccinato, Neme, Torres, Silvério, Pazzini, Rosa e Silva and Ferriani2017). CYP3A4 metabolism is especially relevant for female patients taking quetiapine and lurasidone since these drugs are only metabolised by this enzyme (Table 1). For CYP3A4 substrates, the previously discussed plasma concentration elevating processes are neutralised by this higher CYP3A4 activity, some of which was demonstrated in a large sample of adult patients (Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019). Jönsson et al. (Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019) found smaller sex differences in dose-adjusted concentrations for partial CYP3A4 substrates aripiprazole (n = 1610) and haloperidol (n = 390) than for CYP1A2 substrate olanzapine (n = 10 286), and even lower dose-adjusted concentrations for quetiapine (n = 5853). Moreover, Castberg et al. (Reference Castberg, Westin, Skogvoll and Spigset2017) showed that the blood levels of quetiapine (n = 4316) are similar in males and females before menopause; whereas after menopause, quetiapine concentrations are higher in females compared to that in males.

CYP2D6

Aripiprazole, haloperidol and risperidone are some of the antipsychotics that are primarily metabolised by CYP2D6 (Table 1). According to a population-based study (n = 1376, 23% females, 18–82 years), CYP2D6 activity is 20% higher in women as compared to men (Tamminga et al., Reference Tamminga, Wemer, Oosterhuis, Wieling, Wilffert, de Leij and Jonkman1999). The clinical relevance of this sex difference in CYP2D6 activity is probably small (Aichhorn et al., Reference Aichhorn, Weiss, Marksteiner, Kemmler, Walch, Zernig and Geretsegger2005), as individual differences largely depend on highly variable genetic variations in the CYP2D6 gene (Labbé et al., Reference Labbé, Sirois, Pilote, Arseneault, Robitaille, Turgeon and Hamelin2000). Sex differences may, therefore, only become apparent when female sex hormones reach significant heights (Gaedigk, Dinh, Jeong, Prasad, & Leeder, Reference Gaedigk, Dinh, Jeong, Prasad and Leeder2018; Konstandi, Andriopoulou, Cheng, & Gonzalez, Reference Konstandi, Andriopoulou, Cheng and Gonzalez2020), for example in pregnancy.

CYP219C

CYP219C is responsible for the metabolism of clozapine and other less commonly used antipsychotics (e.g. cyamemazine) (Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018). The population-based study by Tamminga et al. (Reference Tamminga, Wemer, Oosterhuis, Wieling, Wilffert, de Leij and Jonkman1999) (n = 2638, 30% females, 18–82 years) reported a 40% lower enzyme activity in females compared to that in males, which was most pronounced in the age range from 18 to 40 years. Yet, these findings were not replicated in a sample of 330 healthy individuals (n = 611, 18–49 years) (Hagg, Spigset, & Dahlqvist, Reference Hagg, Spigset and Dahlqvist2001).

Excretion

The three major processes that determine renal clearance [i.e. glomerular filtration rate (GFR), tubular absorption and tubular excretion] are all lower in women compared to that in men (Soldin et al., Reference Soldin, Chung and Mattison2011). Since P-gp facilitates renal drug efflux, lower P-gp levels lead to slower renal and hepatic clearance in women as compared to men (Elmeliegy et al., Reference Elmeliegy, Vourvahis, Guo and Wang2020; Nicolas et al., Reference Nicolas, Espie and Molimard2009). After adjusting for body size, GFR is 10–25% lower in females (Whitley & Lindsey, Reference Whitley and Lindsey2009). These differences in renal clearance are particularly relevant for amisulpride, sulpiride and paliperidone, which are cleared mainly by the kidney, leading to much higher plasma levels of these drugs in female patients of all ages (Hoekstra et al., Reference Hoekstra, Bartz-Johannessen, Sinkeviciute, Reitan, Kroken, Løberg and Sommer2021; Li, Li, Shang, Wen, & Ning, Reference Li, Li, Shang, Wen and Ning2020).

Differences in pharmacodynamics between men and women

Oestrogens can modulate the effect of dopamine (Gogos et al., Reference Gogos, Sbisa, Sun, Gibbons, Udawela and Dean2015; Shams, Sanio, Quinlan, & Brake, Reference Shams, Sanio, Quinlan and Brake2016; Yoest, Cummings, & Becker, Reference Yoest, Cummings and Becker2019). According to preclinical evidence, oestrogens influence the levels of dopamine transporters (DATs) and receptors in cortical and striatal regions and by increasing D2 receptor sensitivity in the ventral tegmentum (Vandegrift, You, Satta, Brodie, & Lasek, Reference Vandegrift, You, Satta, Brodie and Lasek2017). A single photon emission computerised tomography DAT study showed an effect of sex (effect size: 0.25), whereby female patients with schizophrenia had a higher ratio of specific striatal binding than male patients (17–53 years) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yang, Howes, Lee, Landau, Yeh and Bramon2013). These sex differences in the organisation of the striatal dopamine system result in higher D2 receptor occupancy in premenopausal women compared to that in men, even when plasma concentrations are similar, whereas postmenopausal women need higher dosages to reach the same efficacy (Fig. 1).

Differences in treatment response between men and women

Meta-analyses on the efficacy of antipsychotic drugs often do not take sex into account (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019; Leucht et al., Reference Leucht, Crippa, Siafis, Patel, Orsini and Davis2020). Yet, based on the limited number of studies that did account for sex, a better response in women has been reported for most antipsychotic drugs (Ceskova et al., Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Libiger, Svancara and Jarkovsky2015; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017; Usall, Suarez, & Haro, Reference Usall, Suarez and Haro2007), except for amisulpride (Ceskova et al., Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Libiger, Svancara and Jarkovsky2015; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Winter van Rossum, Leucht, McGuire, Lewis, Leboyer and Eijkemans2018; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Regenbogen, Sachse, Eich, Härtter and Hiemke2006), risperidone (Ceskova et al., Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Libiger, Svancara and Jarkovsky2015; Labelle, Light, & Dunbar, Reference Labelle, Light and Dunbar2001; Pu et al., Reference Pu, Huang, Zhou, Cheng, Wang, Shi and Yu2020; Segarra et al., Reference Segarra, Ojeda, Zabala, García, Catalán, Eguíluz and Gutiérrez2012; Usall et al., Reference Usall, Suarez and Haro2007) and perhaps clozapine (Alberich et al., Reference Alberich, Fernández-Sevillano, González-Ortega, Usall, Sáenz, González-Fraile and González-Pinto2019). As premenopausal women overall show better treatment response and fewer hospitalisations compared to postmenopausal women (Ayesa-Arriola et al., Reference Ayesa-Arriola, de la Foz, Setién-Suero, Ramírez-Bonilla, Suárez-Pinilla, Son and Crespo-Facorro2020; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Cohen, Horton, Lee, Andersen, Tohen and Tollefson2002; Seeman, Reference Seeman2019; Shlomi Polachek et al., Reference Shlomi Polachek, Manor, Baumfeld, Bagadia, Polachek, Strous and Dolev2017), inconsistent findings may be a result of heterogeneity in age and in duration and severity of illness between study samples. However, all of the abovementioned studies on antipsychotic efficacy fail to account for differences in dose-adjusted plasma concentrations, which may have confounded their results. Specifically, the pronounced sex differences in drug pharmacokinetics and D2 binding rates result in much higher plasma levels in women and especially premenopausal women compared to that in men, even when dose adjustments for body weight are performed (Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019).

The augmentative effect of oestrogens on treatment efficacy is also evident in other patient populations. For example, female patients with anorexia nervosa receiving antipsychotics may benefit from oestrogen augmentation therapy, as these women also have low oestrogen levels (Keating, Reference Keating, Neill and Kulkarni2010). In addition, when women are more sensitive to antipsychotics, they would also be more sensitive to other forms of dopaminergic medications. Levodopa is a precursor of dopamine and is the most potent medication for Parkinson's disease (PD). Indeed, levodopa appears to be more effective at reducing symptoms in female compared to that in male patients with PD (Lyons, Hubble, Tröster, Pahwa, & Koller, Reference Lyons, Hubble, Tröster, Pahwa and Koller1998), whereas female sex is also indicated as a risk factor for levodopa-induced side-effects, such as dyskinaesia and hallucinations (Hassin-Baer et al., Reference Hassin-Baer, Molchadski, Cohen, Nitzan, Efrati, Tunkel and Korczyn2011; Zhu, van Hilten, Putter, & Marinus, Reference Zhu, van Hilten, Putter and Marinus2013).

Side-effects and tolerability

Although higher plasma levels increase bioavailability and efficacy, they also increase the risk for adverse events (Fig. 1) (Castberg et al., Reference Castberg, Westin, Skogvoll and Spigset2017; Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017). Indeed, a large study of 1087 patients between 18 and 65 years with psychotic disorders (48% female) shows that female gender was one of the two main risk factors for severe side-effects, together with polypharmacy, which is also more common in women (Iversen et al., Reference Iversen, Steen, Dieset, Hope, Mørch, Gardsjord and Jönsson2018).

QTc-prolongation

Prolongation of the QTc interval is a side effect of several antipsychotics and may result in life threatening cardiac ventricular arrhythmia such as torsades de pointes (TdP) (Beach, Celano, Noseworthy, Januzzi, & Huffman, Reference Beach, Celano, Noseworthy, Januzzi and Huffman2013). QTc intervals are typically longer in women compared to that in men and female sex is an independent risk factor for developing drug-related TdP (De Yang et al., Reference De Yang, Wang, Liu, Zhao, Fu, Hao and Zhang2011; Makkar, Reference Makkar1993). Although testosterone appears to shorten the QTc interval in men, there seems to be a more complex interaction between progesterone and oestrogen in women (Vink, Clur, Wilde, & Blom, Reference Vink, Clur, Wilde and Blom2018). De Yang et al. (Reference De Yang, Wang, Liu, Zhao, Fu, Hao and Zhang2011) evaluated electrocardiograms of 1006 schizophrenia patients (32% female, 25–75 years) on typical and atypical antipsychotic medication and reported that QTc prolongation was more than twice as common in females (7.3%) compared to that in males (3.2%). Although most antipsychotics can cause QTc prolongation, amisulpride, risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine have the highest risk (Table 1) (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019). Elderly women are more vulnerable for developing TdP as a consequence of QTc prolongation, since sex hormone levels decline whereas additional risk factors for TdP, such as heart disease and electrolyte changes, become more common with increasing age (Danielsson et al., Reference Danielsson, Collin, Jonasdottir Bergman, Borg, Salmi and Fastbom2016; Wenzel-Seifert, Wittmann, & Haen, Reference Wenzel-Seifert, Wittmann and Haen2011). Clinicians should, thus, be wary of the increased risk of QTc prolongation in (older) women, especially those with a (family) history of heart disease.

Extrapyramidal side-effects

Antipsychotics such as amisulpride, risperidone, paliperidone and aripiprazole are associated with a high risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019). Although acute dystonia appears to be less common in premenopausal female patients (Mas et al., Reference Mas, Gassó, Lafuente, Bioque, Lobo, Gonzàlez-Pinto and Bernardo2016), women seem to have a greater risk of developing parkinsonism and akathisia compared to males (Divac, Prostran, Jakovcevski, & Cerovac, Reference Divac, Prostran, Jakovcevski and Cerovac2014), which is likely due to the higher dopamine receptor binding at lower dosages in women (Di Paolo, Reference Di Paolo1994; Seeman & Lang, Reference Seeman and Lang1990; Thanvi & Treadwell, Reference Thanvi and Treadwell2009). The higher risk for women of developing parkinsonism has also been reported in other patient populations that are prescribed antipsychotic medications, for example in patients with dementia (Marras et al., Reference Marras, Herrmann, Anderson, Fischer, Wang and Rochon2012). Multiple reviews indicate that an increased prevalence of EPS in women is associated with a postmenopausal oestrogen decline (da Silva & Ravindran, Reference da Silva and Ravindran2015; Leung & Chue, Reference Leung and Chue2000; Seeman & Lang, Reference Seeman and Lang1990; Thompson, Kulkarni, & Sergejew, Reference Thompson, Kulkarni and Sergejew2000). Long-term exposure to dopamine receptor-blocking agents can cause tardive dyskinaesia (TD), which is also more common in women compared to that in men of all ages (Divac et al., Reference Divac, Prostran, Jakovcevski and Cerovac2014; Yassa & Jeste, Reference Yassa and Jeste1992). The incidence of antipsychotic-induced TD is relatively low in premenopausal women (3–5%), possibly due to the protective antioxidant effects of oestrogens (Cho & Lee, Reference Cho and Lee2013; Wu, Kosten, & Zhang, Reference Wu, Kosten and Zhang2013), but can reach an incidence rate of 30% in postmenopausal women after 1 year of cumulative exposure to antipsychotics (Waln & Jankovic, Reference Waln and Jankovic2013).

Endocrine side-effects

By diminishing the inhibitory effect of dopamine on prolactin secretion in the pituitary gland, antipsychotics often cause hyperprolactinaemia (González-Rodríguez, Labad, & Seeman, Reference González-Rodríguez, Labad and Seeman2020), which can result in galactorrhoea, cessation of normal cyclic ovarian function and hirsutism (Malik et al., Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker2011; Peuskens, Pani, Detraux, & De Hert, Reference Peuskens, Pani, Detraux and De Hert2014). Premenopausal women have physiologically higher levels of prolactin compared to men and are therefore closer to the threshold for hyperprolactinaemia (Kaar, Natesan, McCutcheon, & Howes, Reference Kaar, Natesan, McCutcheon and Howes2020; Riecher-Rössler, Reference Riecher-Rössler2017). Consequently, they are more than twice as likely to develop antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia compared to postmenopausal women and men (González-Rodríguez et al., Reference González-Rodríguez, Labad and Seeman2020; Kinon, Gilmore, Liu, & Halbreich, Reference Kinon, Gilmore, Liu and Halbreich2003). Moreover, prolactin secretion suppresses the production of sex hormones and induces oestrogen deficiency, which is already more frequent in female SSD patients compared to healthy females before menopausal age (Brand et al., Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021; Gogos et al., Reference Gogos, Sbisa, Sun, Gibbons, Udawela and Dean2015; Lindamer et al., Reference Lindamer, Harris, Gladsjo, Heaton, Paulsen, Heaton and Jeste2000; Riecher-Rössler, Reference Riecher-Rössler, Bergemann and Riecher-Rössler2005). Oestrogen deficiency can lead to polycystic ovarian syndrome, infertility, osteoporosis, sexual dysfunction and an increased risk of breast cancer (De Hert, Detraux, & Peuskens, Reference De Hert, Detraux and Peuskens2014; Haring et al., Reference Haring, Friedrich, Volzke, Vasan, Felix, Dorr and Wallaschofski2014; Pottegård, Lash, Cronin-Fenton, Ahern, & Damkier, Reference Pottegård, Lash, Cronin-Fenton, Ahern and Damkier2018; Yum, Kim, & Hwang, Reference Yum, Kim and Hwang2014). For example, up to 48% of women receiving antipsychotic treatment report irregularities in their menstrual cycle (O'Keane, Reference O'Keane2008) and reduced bone mineral density is present in 32% of women treated with prolactin-raising antipsychotics for >10 years (Meaney et al., Reference Meaney, Smith, Howes, O'Brien, Murray and O'Keane2004). Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics (e.g. aripiprazole) should, therefore, be preferred over prolactin-raising antipsychotics (e.g. risperidone) for female patients of all ages (Table 1).

Metabolic side-effects and risk for cardiovascular disease

Women treated with antipsychotics are 1.7 times more likely to develop metabolic syndrome compared to men and are therefore at a higher risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Bener, Al-Hamaq, & Dafeeah, Reference Bener, Al-Hamaq and Dafeeah2014; Carliner et al., Reference Carliner, Collins, Cabassa, McNallen, Joestl and Lewis-Fernández2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lu, Tsai, Chen, Chiu, Jian and Chen2009; Ingimarsson, MacCabe, Haraldsson, Jónsdóttir, & Sigurdsson, Reference Ingimarsson, MacCabe, Haraldsson, Jónsdóttir and Sigurdsson2017; McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Meyer, Goff, Nasrallah, Davis, Sullivan and Lieberman2005). When taking antipsychotics, women are specifically more vulnerable to weight gain and abdominal adiposity (up to 73.4% in women v. 36.6% in men) (Alberich et al., Reference Alberich, Fernández-Sevillano, González-Ortega, Usall, Sáenz, González-Fraile and González-Pinto2019; Kraal, Ward, & Ellingrod, Reference Kraal, Ward and Ellingrod2017; McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Meyer, Goff, Nasrallah, Davis, Sullivan and Lieberman2005; Panariello, De Luca, & de Bartolomeis, Reference Panariello, De Luca and de Bartolomeis2011; Verma, Liew, Subramaniam, & Poon, Reference Verma, Liew, Subramaniam and Poon2009), which is worrisome as abdominal obesity is a strong predictor of diabetes (de Vegt et al., Reference de Vegt, Dekker, Jager, Hienkens, Kostense, Stehouwer and Heine2001). Increased appetite and food intake can be a result of the antagonistic effect of antipsychotics on several neurotransmitter systems (i.e. serotonergic, histaminergic and dopaminergic) (Bak, Fransen, Janssen, Van Os, & Drukker, Reference Bak, Fransen, Janssen, Van Os and Drukker2014). Since most antipsychotics are given at doses higher than required in women (Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Spigset and Reis2019), they are more vulnerable to gain weight from overeating, as high drug plasma levels lead to higher receptor occupancy and thus induce more appetite. Strong associations are particularly found between weight gain and histamine H1 antagonism (Vehof et al., Reference Vehof, Risselada, Al Hadithy, Burger, Snieder, Wilffert and Bruggeman2011). Since oestrogens modulate histamine neurotransmission (Provensi, Blandina, & Passani, Reference Provensi, Blandina, Passani, Blandina and Passani2016), the antagonistic action of antipsychotics on this receptor may also be enhanced by oestrogens, which could explain why the effects on appetite and food intake are stronger in premenopausal women compared to that in postmenopausal women and men. Special attention should be paid to clozapine and olanzapine, which both have the highest affinity for the histamine H1 receptor and the highest risk of being prescribed at doses higher than the required. Unsurprisingly, these antipsychotics are also the ones most strongly associated with weight gain (Kaar et al., Reference Kaar, Natesan, McCutcheon and Howes2020; Smith, Leucht, & Davis, Reference Smith, Leucht and Davis2019). Adequate dosing of all antipsychotics is, therefore, crucial (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019; Kraal et al., Reference Kraal, Ward and Ellingrod2017), and medications that induce minimal weight gain like aripiprazole, may be preferred (Table 1).

Oestrogen deficiency in women can induce several metabolic symptoms, including insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridaemia (Fitzgerald, Janorkar, Barnes, & Maranon, Reference Fitzgerald, Janorkar, Barnes and Maranon2018; Valencak, Osterrieder, & Schulz, Reference Valencak, Osterrieder and Schulz2017). The risk of metabolic dysfunction and CVD is, thus, increased by all factors that cause oestrogen deficiency (e.g. hyperprolactinaemia and menopause) (Regitz-Zagrosek, Lehmkuhl, & Mahmoodzadeh, Reference Regitz-Zagrosek, Lehmkuhl and Mahmoodzadeh2007). Moreover, low oestrogen levels cause abdominal fat accumulation, since oestrogens augment fat accumulation around the hips and thighs rather than upper abdominal areas (Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, Janorkar, Barnes and Maranon2018). This again highlights the importance of avoiding prolactin-raising antipsychotics in women to prevent hyperprolactinaemia.

Special considerations regarding pharmacotherapy in premenopausal women

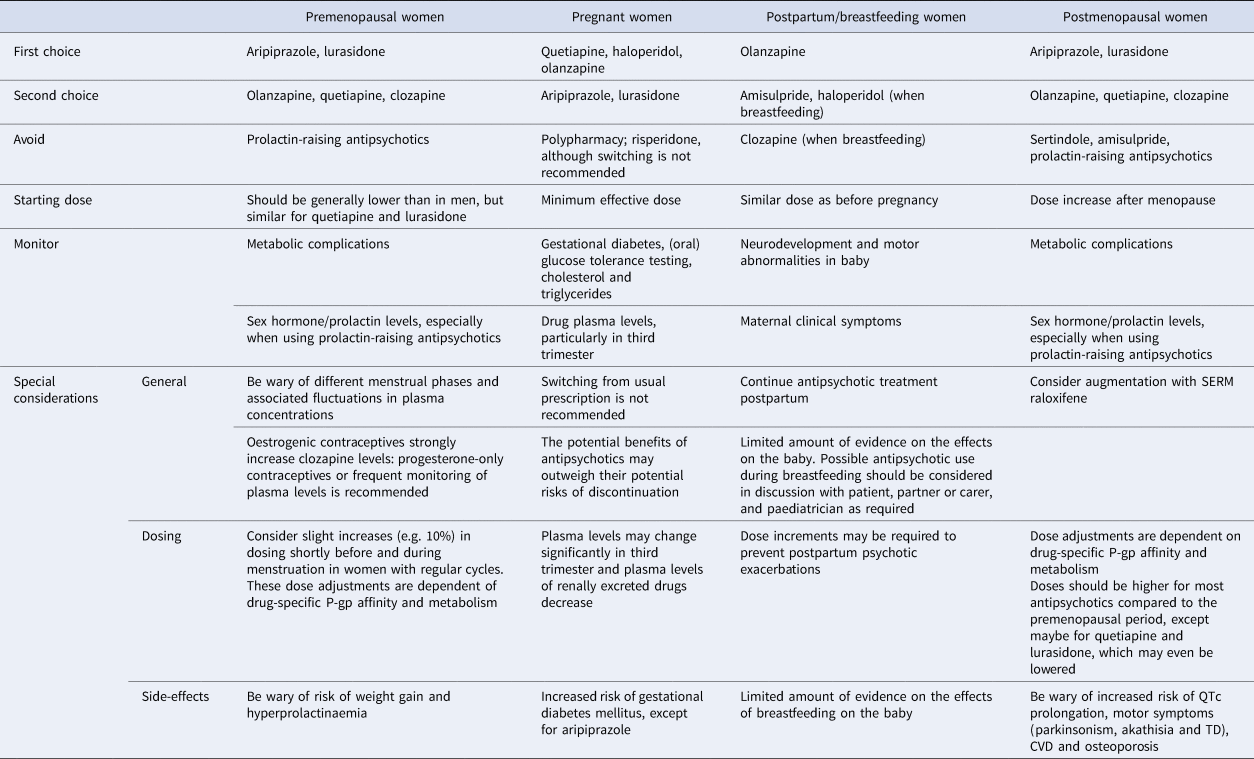

Since pharmacokinetic processes are generally lower in women whereas D2 occupancy rates are higher during high oestrogen phases, dosing of most antipsychotics should start lower in premenopausal women than in men, except for quetiapine and lurasidone. At times when oestrogen levels are high (i.e. during the ovulatory phase), premenopausal women are especially vulnerable to overdosing of drugs metabolised by the CYP1A2 enzyme (olanzapine and clozapine) (Table 1). Although further research is required, it is possible that premenopausal women may, on average, have enough antipsychotic protection from a dose of clozapine and olanzapine that is half of an average male dose (Eugene & Masiak, Reference Eugene and Masiak2017). The interaction between antipsychotics and the menstrual cycle is subject to individual differences and requires further investigation for each type of antipsychotic. In general, women with regular cycles who suffer from psychotic exacerbations during the menstrual phase may benefit from slight dose increments shortly before and around menstruation, although this is rarely done in practice (González-Rodríguez & Seeman, Reference González-Rodríguez and Seeman2019; Lange et al., Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017; Seeman, Reference Seeman2020; Yum, Yum, & Kim, Reference Yum, Yum and Kim2019). Side-effects of antipsychotic drugs that could be particularly relevant to younger female patients include weight gain, as obesity largely decreases self-esteem in women (Connors & Casey, Reference Connors and Casey2006; Lieberman, Tybur, & Latner, Reference Lieberman, Tybur and Latner2012) and hyperprolactinaemia, which reduces oestrogen levels. These low oestrogen levels not only increase the risk for somatic complications but also potentially have also a negative impact on psychotic symptoms (Brand et al., Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021). Aripiprazole and lurasidone may, therefore, be drugs of first choice in this phase and options of second choice are olanzapine, quetiapine and clozapine (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of clinically relevant treatment considerations across different hormonal phases

Interaction between antipsychotics and contraceptives

Women with SSD are usually prescribed contraceptives to decrease the probability of psychotic exacerbations during (pre)menstrual phases of the cycle. Considering the protective effect of oestrogens on psychosis, oestrogenic contraceptives may be preferred over progesterone-only contraception (Brand et al., Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021). Yet, oestrogenic contraceptives also increase the risk of CVD (McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, Wisner, Cattan, Betcher, Stika and Kiley2021; Seeman & Ross, Reference Seeman and Ross2011), making progesterone-only contraceptives (e.g. long-acting reversible contraceptives or intrauterine devices) preferred methods, especially in women over the age of 35 or in those who smoke or who suffer from hypertension (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Tepper, Jatlaoui, Berry-Bibee, Horton, Zapata and Whiteman2016). Oestrogenic contraceptives inhibit CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 activity, increasing plasma concentrations of their substrates (Table 1) (Granfors, Backman, Lattila, & Neuvonen, Reference Granfors, Backman, Lattila and Neuvonen2005; Hagg et al., Reference Hagg, Spigset and Dahlqvist2001; Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018; Ramsjö et al., Reference Ramsjö, Aklillu, Bohman, Ingelman-Sundberg, Roh and Bertilsson2010; Tamminga et al., Reference Tamminga, Wemer, Oosterhuis, Wieling, Wilffert, de Leij and Jonkman1999). For clozapine, plasma concentrations may increase two- to three-fold in the active hormone phase compared with the no-hormone phase, which may result in significant side-effects such as hypotension, sedation and sialorrhoea (Table 2) (Bookholt & Bogers, Reference Bookholt and Bogers2014; McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, Wisner, Cattan, Betcher, Stika and Kiley2021). Progesterone-only contraceptives may be preferable for women treated with clozapine (McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, Wisner, Cattan, Betcher, Stika and Kiley2021). Alternatively, frequent monitoring of plasma levels is recommended when using oestrogenic contraceptives, since oestrogenic birth control may have beneficial effects on the symptoms of SSD (Brand et al., Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021).

It should be noted that there is paucity in studies on this subject; therefore, the effects of hormonal contraceptives on antipsychotic plasma concentration are not clear for other antipsychotic drugs besides clozapine. Based on research so far, it seems there are no clinically relevant changes in the other antipsychotics when combined with contraceptives, although some studies suggest small changes in olanzapine plasma levels (Berry-Bibee et al., Reference Berry-Bibee, Kim, Simmons, Tepper, Riley, Pagano and Curtis2016).

Special considerations regarding pharmacotherapy in pregnant women

Women who take antipsychotics are generally at a higher risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes including congenital malformations, preterm birth, foetal growth abnormalities and poor neonatal adaptation. Compared to healthy, unexposed pregnant women, these women are also more likely to have poor living conditions, poor life-style habits (e.g. smoking, drinking and bad eating habits) and metabolic dysfunctions (McAllister-Williams et al., Reference McAllister-Williams, Baldwin, Cantwell, Easter, Gilvarry, Glover and Young2017; Terrana, Koren, Pivovarov, Etwel, & Nulman, Reference Terrana, Koren, Pivovarov, Etwel and Nulman2015). According to studies that control for these factors, antipsychotics themselves are not significantly associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, small/large-for-gestational-age births, preterm delivery or spontaneous miscarriage (Beex-Oosterhuis et al., Reference Beex-Oosterhuis, Samb, Heerdink, Souverein, Van Gool, Meyboom and Marum2020; Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, Reference Boden, Fergusson and Horwood2011; Cuomo, Goracci, & Fagiolini, Reference Cuomo, Goracci and Fagiolini2018; Damkier & Videbech, Reference Damkier and Videbech2018; Ennis & Damkier, Reference Ennis and Damkier2015; Huybrechts et al., Reference Huybrechts, Hernández-Díaz, Patorno, Desai, Mogun, Dejene and Bateman2016; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, McCrea, Sammon, Osborn, Evans, Cowen and Nazareth2016; Reinstein, Cosgrove, Malekshahi, & Deligiannidis, Reference Reinstein, Cosgrove, Malekshahi and Deligiannidis2020; Tosato et al., Reference Tosato, Albert, Tomassi, Iasevoli, Carmassi, Ferrari and Fiorillo2017; Vigod, Gomes, Wilton, Taylor, & Ray, Reference Vigod, Gomes, Wilton, Taylor and Ray2015). Of note, risperidone has been associated with a higher risk for congenital malformations (relative risk of 1.26) (Huybrechts et al., Reference Huybrechts, Hernández-Díaz, Patorno, Desai, Mogun, Dejene and Bateman2016). Quetiapine, haloperidol and olanzapine are the most frequently investigated antipsychotics in pregnancy, which may be the reason why they are most commonly prescribed during this period (Gentile, Reference Gentile2010; Hasan et al., Reference Hasan, Falkai, Wobrock, Lieberman, Glenthøj, Gattaz and Möller2015; McAllister-Williams et al., Reference McAllister-Williams, Baldwin, Cantwell, Easter, Gilvarry, Glover and Young2017). However, current knowledge on the foetal risks of individual antipsychotics is limited and based on non-randomised studies or case series reports, making it challenging to draw firm conclusions (Damkier & Videbech, Reference Damkier and Videbech2018; McAllister-Williams et al., Reference McAllister-Williams, Baldwin, Cantwell, Easter, Gilvarry, Glover and Young2017). In general, the potential benefits of antipsychotics may outweigh their potential risks of discontinuation. Switching a woman before or during pregnancy from their usual prescription may negatively affect clinical course and well-being. Careful consideration should, thus, guide clinical decisions in women with a diagnosis of SSD at this vulnerable time. In addition, polypharmacy, especially with SSRIs or mood stabilisers should be avoided, as it has been associated with more complications during pregnancy (Table 2) (Sadowski, Todorow, Yazdani Brojeni, Koren, & Nulman, Reference Sadowski, Todorow, Yazdani Brojeni, Koren and Nulman2013). Although lithium is considered to be relatively safe, valproate and carbamazepine are associated with major congenital malformations (Grover & Avasthi, Reference Grover and Avasthi2015).

Pregnant women taking antipsychotics have been reported to have up to a 20.9% higher risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus, especially when using olanzapine, risperidone, clozapine or high doses of quetiapine (>300 mg/day) (Galbally, Frayne, Watson, Morgan, & Snellen, Reference Galbally, Frayne, Watson, Morgan and Snellen2020). Two meta-analyses on this subject confirm this higher risk, although evidence remains insufficient due to significant heterogeneity across studies (Kucukgoncu et al., Reference Kucukgoncu, Guloksuz, Celik, Bahtiyar, Luykx, Rutten and Tek2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wong, Man, Alfageh, Mongkhon and Brauer2021). Pregnant female patients should, thus, be monitored to prevent metabolic complications, with glucose tolerance testing and assessment of cholesterol and triglycerides (Table 2) (Breadon & Kulkarni, Reference Breadon and Kulkarni2019).

Dosing during pregnancy

Physiological changes during pregnancy include increases in plasma volume, drug elimination rates and sex hormone levels (Payne, Reference Payne2019). The activity of albumin and P-gp decrease by 31% and 19%, respectively, in late pregnancy (Abduljalil, Furness, Johnson, Rostami-Hodjegan, & Soltani, Reference Abduljalil, Furness, Johnson, Rostami-Hodjegan and Soltani2012; Ke, Rostami-Hodjegan, Zhao, & Unadkat, Reference Ke, Rostami-Hodjegan, Zhao and Unadkat2014), whereas the blood–brain barrier permeability increases, together leading to higher drug bioavailability. Moreover, renal excretion increases (Segarra et al., Reference Segarra, Aburto, Acker-Palmer, Segarra, Uni-Frankfurt and De Acker-Palmer2020), which results in lower plasma concentrations of amisulpride, sulpiride and paliperidone (Ke et al., Reference Ke, Rostami-Hodjegan, Zhao and Unadkat2014). CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity increases up to 50–100% in the third trimester while CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 activity decreases to up to 40–50% (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Koh and Jeong2013; Hiemke et al., Reference Hiemke, Bergemann, Clement, Conca, Deckert, Domschke and Baumann2018; Payne, Reference Payne2019) (Table 1). Although research on this topic is limited, these metabolic changes appear to have significant consequences on the plasma levels of CYP3A4/CYP2D6 substrates quetiapine (in 35 pregnancies) and aripiprazole (in 14 pregnancies), which were found to be reduced by more than 50% in the third trimester whereas plasma levels of olanzapine (in 29 pregnancies) and clozapine (in 4 pregnancies) were found to be unchanged (Westin et al., Reference Westin, Brekke, Molden, Skogvoll, Castberg and Spigset2018). For clozapine, there is some evidence for increased serum levels in the third trimester (Nguyen, Mordecai, Watt, & Frayne, Reference Nguyen, Mordecai, Watt and Frayne2020). Summarising, drug monitoring and blood level assessment is required throughout pregnancy and becomes increasingly important in the third trimester (Table 2) (Dazzan, Reference Dazzan2021).

Special considerations regarding pharmacotherapy in postpartum women

After birth and especially in the first few weeks after delivery, women with bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or a history of postpartum psychosis are at an increased risk of postpartum psychosis due to hormonal alterations, neuro-immune changes and psychosocial factors (Hazelgrove et al., Reference Hazelgrove, Biaggi, Waites, Fuste, Osborne, Conroy and Dazzan2021; Meltzer-Brody et al., Reference Meltzer-Brody, Howard, Bergink, Vigod, Jones, Munk-Olsen and Milgrom2018). In these women, it is important to closely monitor clinical symptoms in this period and to consider continuation of antipsychotic treatment (Jones, Chandra, Dazzan, & Howard, Reference Jones, Chandra, Dazzan and Howard2014). Of note, pharmacological agents that suppress lactation are usually dopamine D2 agonists and are suggested to increase the risk of postpartum psychosis. This type of medication should, therefore, not be prescribed in postpartum women with SSD (Snellen, Power, Blankley, & Galbally, Reference Snellen, Power, Blankley and Galbally2016).

Breastfeeding

Although breastfeeding has clear benefits for bonding and immunity (Chandra, Babu, & Desai, Reference Chandra, Babu and Desai2015), women with SSD are currently encouraged to breastfeed, unless they are taking clozapine (NICE, 2014). Although all antipsychotics are excreted into the breastmilk, the amount of active ingredients that is transferred to the infant is relatively low (Pacchiarotti et al., Reference Pacchiarotti, León-Caballero, Murru, Verdolini, Furio, Pancheri and Vieta2016). Based on a systematic review of 49 studies, the highest penetration ratio has been found for amisulpride, followed by clozapine and haloperidol (Schoretsanitis, Westin, Deligiannidis, Spigset, & Paulzen, Reference Schoretsanitis, Westin, Deligiannidis, Spigset and Paulzen2020). Anecdotal evidence on clozapine has reported considerable concentrations in breast milk, risk of agranulocytosis in the infant and potentially delayed speech development low (Pacchiarotti et al., Reference Pacchiarotti, León-Caballero, Murru, Verdolini, Furio, Pancheri and Vieta2016). Based on the current literature, positive safety data are most consistent for olanzapine (Zincir, Reference Zincir2019). Apart from clozapine, other common antipsychotics are rarely associated with adverse events (Uguz, Reference Uguz2016), but monitoring of neurodevelopment and motor abnormalities is warranted due to the limited amount of evidence (McAllister-Williams et al., Reference McAllister-Williams, Baldwin, Cantwell, Easter, Gilvarry, Glover and Young2017; NICE, 2014). Taken together, the choice of feeding method and about which antipsychotic is best taken is difficult and should be part of a shared decision process involving the partner and paediatrician (Table 2).

Special considerations regarding pharmacotherapy in postmenopausal women

Most women require a higher dose of antipsychotic medication after menopause, when oestrogen levels decline and the sensitivity to dopamine reduces. In this phase of life, symptoms often increase and menopausal complaints such as sleep disturbances and mood swings can increase the risk of psychotic relapse (Brand et al., Reference Brand, de Boer and Sommer2021; Riecher-Rössler, Reference Riecher-Rössler2017). These dose increments are dependent on drug metabolism. Moreover, dose increments may be smaller or even redundant for lurasidone and quetiapine, since plasma levels of these antipsychotics increase significantly when oestrogen levels decrease.

Amisulpride and sertindole are not recommended as they induce QTc prolongation and typical antipsychotics or risperidone are not the best choice either, as they induce motor symptoms for which older women are more vulnerable (Table 1) (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Mueller, Leweke and Bumb2017; Leung & Chue, Reference Leung and Chue2000). Clinicians should also be wary of drugs more likely to induce metabolic dysfunction and hyperprolactinaemia (Seeman, Reference Seeman2012). This leaves aripiprazole and lurasidone as potential drugs of first choice for postmenopausal women. Quetiapine has a higher risk for certain side-effects and can therefore be drug of second choice. Olanzapine or clozapine are other possible alternatives, as they are associated with higher risks for side-effects as well (Table 2), but may also be more effective than aripiprazole, quetiapine and lurasidone (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter and Leucht2019).

Oestrogen augmentation should be considered at an early stage (i.e. at the beginning of menopause, or even earlier) as this can improve antipsychotic response, reduce psychotic symptoms and relief menopausal complaints (e.g. mood and sleep disturbances and osteoporosis) (de Boer, Prikken, Lei, Begemann, & Sommer, Reference de Boer, Prikken, Lei, Begemann and Sommer2018; Heringa, Begemann, Goverde, & Sommer, Reference Heringa, Begemann, Goverde and Sommer2015). As oestrogen replacement also increases bone mineral density, the prevention of antipsychotic-induced osteoporosis is a secondary benefit. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as raloxifene are more suitable for long-term use compared to oestrogens, since SERMs have oestrogenic effects on the brain and bone tissue but anti-oestrogenic effects on other tissues (such as breast and uterus) (Arevalo, Azcoitia, & Garcia-Segura, Reference Arevalo, Azcoitia and Garcia-Segura2015). As hormone replacement therapy with either oestrogens or SERMs is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic events (Ellis, Hendrick, Williams, & Komm, Reference Ellis, Hendrick, Williams and Komm2015), potential benefits and disadvantages should be balanced individually. For example, a (family) history of thrombo-embolic events may be a reason not to opt for oestrogen replacement therapy.

Conclusion

Women tend to have slower drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination rates, resulting in higher plasma levels and bioavailability of most antipsychotic medications. Since oestrogens induce dopamine sensitivity in the brain, the efficacy of antipsychotics is enhanced in premenopausal women, compared to men. Considering that current treatment guidelines are mostly based on data from men, women are likely to be overmedicated and it is therefore not surprising that adverse events are much more common in women. Additionally, women are more vulnerable to many side-effects, such as weight gain, EPS and hyperprolactinaemia, independently of dose. Defining the minimum effective dose in women is of utmost importance, as the risk of overmedicating increases when female sex hormone levels are high, specifically during ovulation and in the later stages of pregnancy. Conversely, effective doses of most antipsychotics (quetiapine and lurasidone are exceptions) may need to be increased during low-hormonal phases in life, specifically post-natal, during menstruation and during and after menopause. Optimal antipsychotic treatment for women is highly dependent on the different life phases. Premenopausal women should be prescribed lower dosages for most antipsychotics (except for quetiapine and lurasidone). During pregnancy, the most reasonable and less harmful choice appears to be maintaining future mothers with SSD at the minimum effective dosage of the drug they were already using before pregnancy. If a medication-free pregnancy is feasible, this is of course the best option. Clozapine should probably be avoided during breastfeeding and while further safety data on other antipsychotics are limited, the inherent benefits of breastfeeding for mother and baby should be balanced carefully against the potential risks for the baby. Postmenopausal women represent a group of patients that is especially vulnerable to side-effects associated with ageing and declining hormone levels such as osteoporosis and CVD, and for these women, oestrogen replacement therapy should be considered to ameliorate both somatic and mental health problems, although the increased risk for thrombosis also needs to be taken into account.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.