Introduction

This case study was prompted by the identification, in observations and in discussion with the normal class teacher, of pupil demotivation and disaffection during Latin lessons, and the fact that this represented a considerable barrier to attainment and progress. My observation of this phenomenon coincided with Year 9 submitting their GCSE options. The combination of apparently ambiguous attitudes towards the subject and the fact that these attitudes were being brought to the fore explicitly because of the options choices drew my attention to pupil perceptions of the subject. It seemed to me that understanding the way in which pupils perceive the subject might be instructive for my own teaching practice, allowing me to better understand what pupils enjoy about the subject, what they find difficult, what enthuses them and what turns them off. Furthermore, the place of Latin within schools in general, and the particular school in which I conducted this study, is not something that should be taken for granted. It seemed to me, therefore, that this case study might provide some insight into whether Latin is a subject that young people feel is relevant and perhaps might offer some insight into what can allow Latin to have as inclusive an appeal as possible.

The school in question is an urban, voluntary-aided Church of England school of approximately 1700 pupils. The school's admissions policy gives priority to pupils from Christian backgrounds which is calculated based on church attendance. According to an Ofsted section 8 inspection carried out in in 2014, the proportion of pupils with a statement of Special Educational Needs is ‘low’, as is the proportion of pupils eligible for pupil premium (Ofsted, 2014). The school also has very few pupils who speak English as an additional language (Ofsted, 2014). In the most recent Ofsted inspection, the school was rated outstanding (2012).

All pupils at the school learn Spanish as their first modern foreign language in Year 7. They are then given the opportunity of electing to study a second language in Year 8 or, alternatively, to follow an applied studies course. Latin, alongside French and German, is one of the options that pupils have for a second language in Year 9. Pupils have then studied the subject for approximately four and a half terms before making their GCSE choices in Year 9. However, as a result of a reorganisation of the school curriculum (effective from 2015 onwards) by the school's academic board (composed of members of the senior leadership team and governors), pupils are now required to drop a subject at the end of Year 8. As a result, pupils are now faced with the choice of whether or not to continue studying Latin after less than a year, and I would suggest this increased pressure renders some understanding of pupils’ perceptions of the subject even more valuable.

The class upon which this case study focuses is a mixed-ability Year 9 group of 24 pupils (16 girls and eight boys). The group includes one pupil who has Special Educational Needs, three pupils who are identified as Gifted and Talented, and three pupils who are eligible for pupil premium. The school in question uses the Cambridge Latin Course as the primary material for the teaching of Latin. The teachers endeavour to use the Cambridge Latin Course broadly as it was intended (this will be discussed at some length in the literature review) and largely avoid a more traditionalist, grammar-based approach to the teaching of Latin. The teachers also endeavour to devote a portion of teaching time to the socio-historical, paralinguistic material in the Cambridge Latin Course.

The literature review that follows considers some of the literature that has focused on the place of Latin in education and how it can secure its status as a subject that is appealing and relevant to modern pupils.

Literature review

In this literature review, I will concentrate on the place and identity of Latin in the school curriculum and on research done into pupil perceptions of other subjects, particularly modern foreign languages.

The place of Latin in the school curriculum

It has long been recognised that the place of Latin in the school curriculum is far from secure. Forrest documents two crucial crises that have threatened (and shattered) the once central place of Latin in the curriculum: the decision of Oxford and Cambridge Universities to remove the O-Level Latin matriculation requirement and the move towards comprehensive education (Forrest, Reference Forrest1996). Whilst these events may have been crucial turning points in the place and identity of Latin in the curriculum, it is also important to recognise the broader social context in which they occurred, rather than just a factual history of its decline (and renaissance), particularly if we are to develop a clearer understanding of perceptions of the subject. Gay contextualises Forrest's two ‘crises’ in ‘a mood of anti-elitism and egalitarianism’ and a questioning of ‘old assumptions about cultural and political hegemony’ (Gay, Reference Gay and Morwood2003, p. 74). It was in this social and political climate that Latin, so long identified as ‘the sole domain of the ‘more able’ (Tristram, Reference Tristram and Morwood2003, p. 7) and symbolic of ‘class-based socioeconomic elitism’ (Paul, Reference Paul, Hardwick and Harrison2013, p. 153), came under particular threat in British schools in the second half of the 20th century. These comments evince two of the most significant ways in which Latin was negatively perceived: that it is both intellectually and socially elitist.

These negative associations were based in part on the manner in which learning Latin was linked to ‘upper-class cultivation’ (Sharwood Smith, Reference Sharwood Smith1977, p. 28), but also on the manner in which the subject was taught. Sharwood Smith refers to a time ‘in the not-so-distant past, when the learning of […] Classical Latin was seen as an end in itself’ (Sharwood Smith, Reference Sharwood Smith1977, p. 27) without concern for the broader relevance of the activity. For many, this focus on the language, one which was of no practical value for the vast majority of students, led to a perception that it had no role in the inclusive educational system of a democratic country. As a result of this negative perception, considerable thought was given to justifying the place of Latin in schools. Broadly speaking, the arguments in favour of studying Latin can be divided between the utilitarian arguments (that learning Latin helps you understand other languages, and that it develops your problem-solving skills etc (see, for example, DES, 1988)) and the arguments of those which seek to justify it based on the inherent worth of the subject matter (see, for example, Peters, Reference Peters1967, for a refutation of utilitarian arguments).

As a response to the crises detailed above and the perception of Latin as elitist, exclusive and irrelevant, the Cambridge Schools Classics Project was set up in 1966 and developed the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC) in an attempt to revolutionise and save the teaching of Latin. In an effort to address the issue of inclusivity, the Cambridge Schools Classics Project states its aim as ‘to help make the classical world accessible to as many students as possible – whatever their age or background’ (CSCP, 2016b). In order to achieve this aim, the CLC employed methods which were radically different to those which had traditionally used in the teaching of Latin. Originally, it sought ‘to develop materials and techniques which will accelerate and improve pupils’ ability to read classical Latin literature and widen their knowledge of classical civilisation’ and ‘to develop materials and courses for the non-linguistic study of Classics, with particular reference to widely varying levels of pupil ability’ (CSCP, 2016a). The CLC intended that pupils should learn grammar inductively through translating stories, set in and based on the Roman world, which would provide context and motivation for pupils’ study. The CLC currently states a belief that ‘motivated students are more likely to make the effort to master the language and gain more knowledge and understanding of Roman culture and literature’ (CSCP, 2016b). For the CSCP, motivation is crucial for pupils to be able to achieve success in the subject. Seeing as it is unlikely that pupils will primarily be motivated by extrinsic factors in their study of Latin it is important that any course provides intrinsic motivation. For the CLC, this is done not only with the story, but also through the paralinguistic material which supports pupils in gaining insight into what the CLC believes is the inherently interesting world of the Romans.

Llewelyn Morgan confidently claims that ‘no one, or at least no one who knows what they're talking about, is calling Latin ‘exclusive’ or ‘elitist’ anymore. Latin is classless’ (Pelling & Morgan, Reference Pelling and Morgan2010, p. 6). However, in his consideration of the conditions needed for Latin to thrive in the modern curriculum, Lister suggests that ‘overcoming misconceptions about Classics is an important first step in persuading staffroom doubters that Classics has a right to be included’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, pp. 158–9). The fact that Lister still sees overcoming misconceptions as a crucial first step suggests that perceptions of Latin remain a potentially considerable barrier to the health of Latin in British schools. Paul also lends support to the view that perceptions of Latin are not altogether positive, arguing Latin is still not free of ‘accusations of and assumptions about its elitism’ and particularly its intellectual elitism (Paul, Reference Paul, Hardwick and Harrison2013, p. 153). Paul (Reference Paul, Hardwick and Harrison2013) refers to statistics which indicate that roughly 60% of those pupils taking Latin GCSE exams are educated in independent schools. Furthermore, she cites research which indicates that only 65% of the state schools which offer Latin say that it is open to all and that instead it is offered to certain pupils based on ability. In this respect, therefore, the inclusivity of Latin still appears to be challenging. Arguably correctly (based on the statistics cited by Paul, Reference Paul, Hardwick and Harrison2013), the perception appears to endure that Latin remains a subject that is not for all.

This picture of Latin as an intellectually elitist subject is further supported by research completed by the Curriculum Evaluation and Management Centre which finds that Latin is relatively more difficult than other subjects (Coe, Reference Coe2006). The data for the study were taken from the national pupil database for pupils in maintained mainstream schools in England in Key Stage 4 exams from 2004. Coe used the Rasch model, which assumes that the difficulty of the exam and pupil ability can be measured on the same scale, with the difference between ability and difficulty of the exam determining the probability of success. According to the Rasch mode, Coe found Latin to be ‘about a grade harder than the next hardest subject’ (Coe, Reference Coe2006, p. 9). Referring to this research, Weeds comments that ‘it can't help the cause of Classics if public perceptions are that it is difficult’ (Weeds, Reference Weeds2007, p. 11). Interestingly, his concern is with the broader public perception of Classics, rather than the experience of those pupils who are studying the subject. I would argue that, whilst this data about the relative difficulty of Latin is interesting, it can only do so much to allow us to understand the choices made by those pupils who are studying Latin. Whilst the GCSE exam will clearly have a bearing on the material that is covered prior to undertaking a GCSE course, it should be recognised that it is the material covered and the teaching style prior to beginning the GCSE that will be responsible for either interesting or driving off pupils.

Among those writing about Latin teaching, the focus is on the perceptions of the subject beyond the classroom. As Weeds (Reference Weeds2007) referred to the opinions of the public, Lister (Reference Lister2007) is concerned with teaching colleagues when it comes to the perceptions of Latin. This concern is understandable, given the intense pressure that Latin can be and is under in schools in Britain. Latin requires broader advocacy in order to ensure the health of the subject. However, I would argue that it is crucial that pupil experiences of learning Latin remain the focus of considerations of how Latin should be taught. It is by understanding how pupils perceive the subject that we may ensure that Latin teaching and learning can best serve pupils in schools now and thereby reinforce the security of the subject.

Research into pupil perceptions of Modern Foreign Languages

Prompted by either stagnant (Stables & Wikeley, Reference Stable and Wikeley1999) or falling (Fisher, Reference Fisher2001) numbers of pupils opting to study Modern Foreign Languages at GCSE and A level, some research has been published on the subject of pupils’ perceptions of Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) lessons. Whilst the challenges facing MFL may not be as acute as those facing Latin (at least in terms of pupil numbers), this research provides a useful context for an overview of pupil perceptions of Latin. In part this is due to the similar nature of the subjects; however, it is also due to the similarity between the historically negative image of Latin (in terms of difficulty and irrelevance) and the issues faced by MFL in terms of pupil perception.

The two studies to which I refer (Stables & Wikeley, Reference Stable and Wikeley1999; Fisher, Reference Fisher2001) adopted research methods which were broadly similar to those I adopted for this case study. In both studies, initial questionnaires were followed by interviews; however, whereas Stables and Wikeley (Reference Stable and Wikeley1989) focused their study on pupils at ages 14 and 15, Fisher (Reference Fisher2001) concentrated on post-16 recruitment, surveying the attitudes of pupils from Years 11 to 13.

Despite the fact that the two studies surveyed pupils at different stages in the school careers, there were elements of pupil perceptions of MFL that were evident in both. Both studies suggested that MFL does not fare well in terms of pupil enjoyment (Stables & Wikeley, Reference Stable and Wikeley1999, p. 30 and Fisher, Reference Fisher2001, p. 35); however, Fisher points out that it was more the case that pupils found other subjects more appealing rather than that they particularly disliked MFL. Stables and Wikeley (Reference Stable and Wikeley1999) argue that it is a particular issue that MFL is not seen as enjoyable given that the pupils surveyed lacked extrinsic motivation in the subject due to its perceived lack of instrumental value (Stables & Wikeley, Reference Stable and Wikeley1999, p. 30). Although Fisher's (Reference Fisher2001) finding suggested a more positive view of the perceived instrumental value of MFL the issue raised by Stables and Wikeley (Reference Stable and Wikeley1999) remains pertinent to Latin. Since Latin lacks obvious instrumental value and any utilitarian value is seen in terms of the development of secondary, transferable skills, it is crucial that pupils perceive the subject as intrinsically appealing.

Another recurring observation was that pupils found MFL difficult (Stables & Wikeley, Reference Stable and Wikeley1999; Fisher, Reference Fisher2001). This potentially offers an interesting point of context for research into pupil perceptions of Latin given that it has already been discussed that Latin GCSEs are relatively difficult; however, Fisher's (Reference Fisher2001) research offers additional valuable insight into the experience of language learners that may offer a useful point of comparison for the experiences of Latin pupils. According to her research, pupils demonstrate low levels of confidence in the subject (in many cases even when on target for high grades) and commented on a fear of ‘getting it wrong’ (Fisher, Reference Fisher2001, p. 35). Indeed, a fear of failure may well represent a considerable barrier to success in Latin, a subject in which pupils are faced with material of considerable complexity and in which making educated guesses is valuable for progress. This link between the complexity of languages and perceived difficulty (something potentially shared by MFL and Latin) is reinforced as Fisher (Reference Fisher2001) suggests that grammar was the element of MFL that pupils found most difficult and least enjoyable. This issue is one that the CLC endeavoured to address by attempting to structure the course so that grammar could be learned inductively and reinforced through reading the stories, with very few exercises to practise grammatical rules. However, in Fisher's Reference Fisher2001 study, A level pupils, both linguists and non-linguists, said they would have appreciated a firmer grounding in basic grammar and Fisher herself recommends the introduction of more grammar lower down the school as a measure to improve the uptake of MFL. We are, therefore, apparently faced with a paradox whereby pupils require a firm grounding in grammar in order to feel secure in the subject and yet also perceive grammar learning to be particularly difficult and unenjoyable.

Fisher (Reference Fisher2001) offers a third valuable point of context for a study into pupils’ perceptions of Latin in terms of what she tells us about pupil perceptions of para-linguistic study. Her findings indicate that a greater level of content related to the culture of the target language would have been appreciated by pupils. She quotes a pupil who comments that learning about the culture ‘completely takes it [language learning] out of the textbook and it makes it much more interesting’ (Fisher, Reference Fisher2001, p. 38). On an arguably related note, Fisher also identifies the mundane nature of the topics covered in MFL courses as a considerable barrier to pupil engagement and enjoyment, with pupils desiring relatable content and/or material that is more ‘intellectually challenging’ (Fisher, Reference Fisher2001, p. 37). The issues that emerge here (a lack of engaging material and meaningful context for the work) were ones that the CLC attempted to address in its inception by creating a reading course which featured an engaging plot, grounded in the real, historical world of the Romans. As a result, we may hope that pupils do not perceive the same issues in terms of mundane content as an issue for Latin and this is something that I hope this case study may reflect.

It should be noted that the research described above explores why pupil numbers have fallen in MFL. In comparison, this case study is interested in exploring what pupil experiences and perceptions of the subject are and whether this is linked to pupils’ choices regarding future study. Whereas the MFL studies explore the pupils’ negative perceptions of MFL, I am not primarily seeking to explore the negative side of pupils’ experiences of Latin.

As this literature review indicates, questions remain as to whether Latin has fully succeeded in undergoing the democratisation which it required and for which many committed reformers have striven. When we consider the particular history of Latin and the negative associations of elitism which it has apparently not entirely shaken, I would argue that it is particularly important that we remain sensitive to the way in which pupils perceive their subject. I would argue that this is further reinforced when we look to the research done into pupils’ perceptions of MFL. We see that questions of difficulty, particularly regarding grammar, and relevance are primary factors in pupils’ feelings of aversion to the subject. We may reasonably suppose, given the statistics concerning the difficulty of Latin and the fact that Latin is no longer a spoken language, that negative perceptions of Latin may be based on a similar group. However, given the aims of the CLC to provide a course that is inherently interesting and motivating to students, we may tentatively hope that Latin escapes being labelled as mundane.

It is in attempt to explore these issues in the perception of Latin that I undertake this case study.

Research questions

Having observed the widely varying levels of pupil engagement during Latin lessons and having read about both the issues that Latin teaching has sought to address in attempting to secure its place in the modern curriculum and the issues that have been identified more recently in MFL teaching and recruitment, I set out to address the following research questions:

• What are the learning experiences of pupils studying Latin in the particular Year 9 Latin group in question?

• Why have pupils opted to either continue with or drop Latin?

There is considerable overlap between the two questions as, of course, the learning experience will have a considerable bearing on pupils’ reasons regarding their subject choices. Broadly speaking, the two questions are encompassed within the topic of pupil perceptions of Latin as the learning experience will define and be defined by perceptions of the subject and perceptions of the subject also impact on the choices that students make.

Methodology and Method

In order to gather the information for this case study, I used two research methods. Initially, I used a questionnaire (Appendix 1) which pupils filled in anonymously during lesson time. This was then followed by group interviews of two to five pupils.

Prior to presenting pupils with the questionnaire or asking any pupils to be involved in interviews, I informed pupils of the nature and purpose of the research that was being carried out and that they could decline to participate with no consequences, as is required by the British Education Research Association (BERA, 2011, p. 5–6).

The questionnaire was designed to provide a broad insight into pupils’ thoughts and experiences of learning Latin and their reasons for their choice regarding GCSE Latin (whether to take it or not). The first question asked pupils whether or not they had chosen to continue with the subject in order to contextualise their subsequent responses concerning their enjoyment of the subject. I used response scale questions to gather information from all pupils about their enjoyment of the subject and then about their reasons for the decisions they had made concerning GCSE.

The major benefit of using a questionnaire was that I could efficiently survey the thoughts of the whole class. Bell (Reference Bell2005) identifies time constraints as a major consideration of any research project and the questionnaire allowed me to obtain data quickly (the questionnaire was administered in 15 minutes of lesson time). Furthermore, the questionnaire provided me with data with which to triangulate the responses given during interview. The decision to make the questionnaire anonymous, rather than confidential, allowed pupils greater freedom to respond honestly and without inhibition. The questionnaire also provided a useful bank of data with which to compare the more in-depth responses produced by the interviews. By asking pupils to begin by clarifying whether or not they had opted to take Latin to GCSE, I was able to divide the data into two sets: one for pupils who are continuing and one for pupils who are not. This allowed me to see if any patterns emerged regarding the activities that pupils enjoyed based on whether or not they were continuing with the subject.

Group interviews were used after the initial questionnaire in order to allow me to develop a more in-depth view of pupils’ perceptions of Latin. I opted to use group interviews instead of individual interviews in an attempt to provide pupils with a greater sense of security in which they could share their views on the subject. I determined the groups to be interviewed based on my observations of the class during teaching in order that, where possible, pupils were interviewed in socially coherent groups (i.e. with friends). The groups for interview were also comprised so that the members of the group had made the same choice regarding continuing with or dropping Latin. The weakness of using group interviews was, as Bell (Reference Bell2005) suggests, that louder and more confident personalities tended to dominate the responses. Hayes (Reference Hayes2000) comments on the importance of careful selection in order to balance groups for interviews correctly, and I attempted to do this by organising the groups with social groups in mind. As a result, I felt that I mitigated against the possibility that interviews might be dominated by particular individuals and particularly against the concern that some individuals might feel uncomfortable to air their views in front of the other interviewees (Bell, Reference Bell2005). Another issue was that, due to time constraints and the fact that some pupils declined to be interviewed, I was not able to capture the results of all pupils surveyed in the questionnaires. This is obviously a shortcoming of the research in terms of capturing the opinions of the whole group; however, by interviewing groups that represented the different choices made for next year, I endeavoured to mitigate against this as well.

The questions asked during the interview followed essentially the same structure, asking first why pupils chose the subject in the first place, then asking about their experiences and enjoyment of the subject, leading on to a question about their reasons for their GCSE choice regarding Latin. This was followed up with questions about their opinion of Latin as a subject, rather than their experiences of studying the subject. Further questions were asked as appropriate in order to clarify comments made by the pupils or to elicit further information. This questioning allowed me to produce qualitative data which could be compared with the quantitative data produced by the questionnaire. The responses given in the interview were recorded and then transcribed. Relevant extracts from these transcriptions are attached as appendices.

Data Analysis

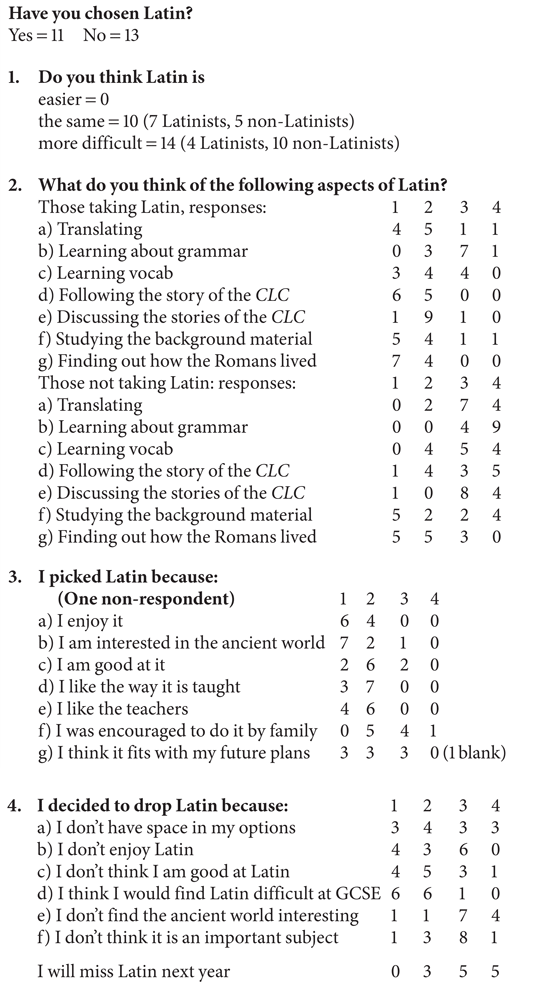

One of the elements of pupils’ experiences of learning Latin that became clear from the questionnaire was that Latin is perceived as difficult. Of the 24 pupils surveyed, 58% said they thought Latin is more difficult than other subjects with 42% saying it is of the same level of difficulty. As is perhaps to be expected, of the 13 pupils who have not chosen Latin to GCSE, the majority (77%) said they found Latin more difficult than other subjects. This perception of the difficulty of Latin is one that was reinforced in the group interviews. One pupil who is not continuing with the subject commented:

Pupil I: I enjoyed it more at the start of the year but as it's got more difficult, I don't really enjoy it now.

[…]

I know … it should be hard, but it's really difficult. There's so many different cases and tenses and I'm just so confused now.

Interestingly, the pupil in question here appears to recognise that there may be value to subjects and schoolwork that is not easy; however, it appears that frustration at the complexity of the grammar is the overriding feeling associated with Latin.

This attitude towards the grammatical side of pupils’ Latin learning was seen elsewhere, with only 13% of students expressing positive feelings towards learning about grammar in the questionnaire and 42% expressing dislike. The interviews were also illustrative:

Pupil L: I don't like learning grammar because I just forget everything.

[…]

Pupil K: It's easy to translate it but it's when you're asked to put it in like what case it's in and stuff, that's hard.

Pupil O: … learning grammar by itself can be harder but when it comes to putting it into the translation it feels more natural.

What emerges is that pupils perceive grammar to be confusing and difficult, particularly when teaching and learning focuses on grammar specifically. Pupil O agrees with Pupils L and K in finding grammar difficult; however, Pupil O offers a more nuanced view. Whilst teaching and learning that is focused on grammar is apparently unappealing and difficult for this student, the pupil suggests that grammatical rules make more sense when put into practice in the meaningful context of translation. Furthermore, Pupil O arguably shows recognition of the value of ‘learning grammar’, as they implicitly recognise that their translation is based upon grammar rules. Arguably, here we see an articulation of the conflicted perception of grammar among pupils to which Fisher referred (Reference Fisher2001, pp. 36–7), whereby grammar is necessary for secure understanding, but also unappealing and intimidating.

Interestingly (and perhaps as was implied by Pupil I above), the difficulty of Latin was not always perceived as a problem and the perceived challenge of the subject was seen as attractive to some. When asked to explain why they enjoy Latin, Pupil E explained that, ‘It challenges me more than other subjects.’ However, Pupil F drew a distinction suggesting, ‘It's more challenging, not more difficult [than other subjects]’. Although it was not entirely clear how the pupil in question distinguished between challenging and difficult (perhaps challenging implies confidence in their ability to complete a task which requires some thought?), the perception of Latin as a difficult subject is reinforced again, even from pupils who enjoy the subject and are continuing with it (as is the case with Pupils E and F).

Another comment made by a pupil, which relates to the perceived difficulty of the subject and is also illustrative of the identity of the subject in the pupils’ eyes, was that ‘It's more for the clever people… like the brighter people’ (Pupil I). Whilst the preceding quotes from students demonstrated their own experiences of Latin as a difficult subject, this comment more explicitly conveys a sense of intellectual elitism that is associated with the subject. Pupils do not only seem to consider Latin a difficult subject based on their personal experiences, we also see the implication that Latin is a subject that is appropriate for and targeted at the most able.

One thing that certainly becomes clear is that there is a link between the perceived difficulty of Latin and pupils’ choices regarding whether or not to continue. In the questionnaire, of the 13 pupils not taking it to GCSE, 12 indicated that they either strongly agreed or agreed that they thought they would find Latin difficult at GCSE. This compared with eight of the ten pupils taking Latin saying they agreed or strongly agreed that they took Latin because they are good at it. The evidence (both from the questionnaire and interviews) suggests that pupil confidence in the subject (which is not necessarily the same as perceiving the subject as difficult) is strongly linked with whether pupils choose to take the subject as an GCSE option.

It seemed that pupils’ perceptions of Latin were also influenced by factors beyond lessons. One pupil remarked that, ‘When you tell other people that you've picked Latin, they go, ‘What've you picked that for?’’ (Pupil I) and this was echoed by Pupils K and L (speaking in a different group interview) who said, ‘Lots of people say it's a pointless language… I don't think it is….’ and, ‘People who do German and stuff say, ‘Why do you do Latin? Why do you do Latin?’’ These comments seem to indicate that Latin students are aware of a negative perception of the subject, particularly among their peers; however, their peers’ negative perception of Latin does not necessarily seem to have had an adverse effect on the pupils studying Latin. Indeed, the pupils who referred to the opinions of others did so in order to make the point that they considered these negative opinions misguided.

It has already been discussed that the difficulty of Latin features as a major element in how the subject is perceived by pupils and as a factor that is linked to the choices pupils make regarding continuing with or dropping the subject. In the interviews particularly, the perceived relevance of the subject also emerges as a significant factor in pupils’ overall perception of Latin. When asked to comment on whether they thought Latin is a relevant subject, pupils’ responses often focused on the beneficial impact that learning Latin can have on other subject areas. In response to the question ‘Do you think Latin is relevant?’, Pupil B responded, ‘Yeah, I think I have a better understanding of English’, and others commenting that ‘It helps with other subjects’ (Pupil K), that ‘It can help a lot with other languages’ (Pupil L) and that ‘It… makes learning modern languages easier in some ways because they all stemmed from Latin’ (Pupil H). One pupil also linked the relevance of the subject to the challenging nature of Latin: ‘[it] is relevant because it helps sort of keep your brain working’ (Pupil F). These responses suggest that, perhaps unsurprisingly, pupils link the relevance of the subject to its instrumental value. Even Pupil F, who does not concentrate on the benefits Latin can offer in the study of other subjects, articulates the benefits of Latin in utilitarian terms, as something to sharpen the mind, rather than based on the inherent appeal and interest of the subject.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, when those not continuing with Latin were asked (on the questionnaire) whether they decided to drop Latin because they don't think it is an important subject, nine out of 13 pupils either disagreed or strongly disagreed. Whilst we might have anticipated that those who are dropping Latin might be doing so because they see Latin as irrelevant and unimportant, this does not necessarily appear to be the case. It should be noted that there is a difference between the questions that were posed to pupils on the questionnaire and in the interview. Pupils may have disagreed with the statement that they decided to drop Latin because they do not think it is important simply because other factors were of greater significance. It is also possible that pupils may have perceived a difference between the importance and the relevance of the subject; they may think Latin is important because it is the Latin from which modern languages derive but that it is irrelevant because they will not need to speak it. It is, however, interesting to see that perceived unimportance of Latin does not appear to be a common reason that pupils chose to drop the subject.

Despite this, perhaps unsurprisingly, there were also a number of responses that indicated Latin is not seen as an entirely relevant subject. The view that Latin is not relevant because it is not a spoken language was seen explicitly on three occasions: ‘I wouldn't say it's as relevant [as MFL] … because … [with MFL] you can go out and go to that country’ (Pupil G); ‘I don't think it's relevant because we don't speak it’ (Pupil A); ‘people say it's a dead language, so I don't know what it would help me with personally’ (Pupil I). Again, we see the negative perception of Latin's relevance as something that is linked to a lack of instrumental benefit. We also see that pupils are quick to draw comparisons between Latin and MFL. All the above comments were made when pupils were asked whether they thought that Latin is a relevant subject, not whether they thought it is more or less relevant than MFL. This is not necessarily surprising, particularly in a school in which Latin teachers are members of the Languages department, rather than a Classics department, and in which French and German are the alternatives to choosing Latin. It is notable, however, that pupils did not draw comparisons between Latin and History, despite the socio-historical nature of the subject matter of the CLC.

The way in which pupils seem to conceptualise Latin, based on the comparisons they draw with other subjects, can be perhaps be better understood if we consider pupils’ experiences of learning Latin, as opposed to their perception of the subject as an academic discipline (upon which I have concentrated thus far). When asked whether they enjoyed certain aspects of learning Latin, 21 out of 24 pupils said they either enjoyed or greatly enjoyed finding out how the Romans lived. This response implies a clear level of enthusiasm for the ancient world and suggests that Classical subject matter is of inherent interest. In line with this, comments on the paralinguistic material were positive in the interviews: ‘I like learning about the background of Latin, like the historical bit’ (Pupil I); ‘I … like the background information … you're learning a bit about what it was like back for people living back then’ (Pupil O). However, interestingly, pupils’ responses in the questionnaire to what they thought of studying the background material from the CLC were more mixed. 16 found this either enjoyable or greatly enjoyable, while three said that they didn't mind it and five that the disliked it. This appears to suggest that pupils do not necessarily equate learning about the Romans with the background material of the CLC; however, it should be noted that the wording of the question may have had an impact on these responses. Pupils may have seen a difference between the idea of ‘studying’ background material as opposed to ‘finding out about’ the Romans. I would suggest that ‘studying’ perhaps implies a formal learning activity, whereas ‘finding out about’ implies a greater level of freedom and informality that may have been appealing. Arguably, the fact that pupils are more enthusiastic about having more freedom to engage with the Classical world is consistent with the idea that this subject matter is of inherent interest. Of course, we might uncharitably suspect that this preference for implicitly less formal learning activities stems from the perception that this might represent an ‘easy option’, requiring less effort from pupils.

Pupils’ responses typically showed a greater level of ambivalence, and at times antipathy towards, learning activities which had a more linguistic focus. In the questionnaire, learning about grammar emerged as the least popular aspect of Latin by a distance (only three pupils said they liked it) and it has already been discussed that pupils commented in the interviews on how grammar represents the most difficult aspect of the subject. The questionnaire indicated a more ambivalent attitude within the class towards translation: nine pupils either enjoyed or really enjoyed it, eight didn't mind it and five disliked it. Whereas grammar had been unpopular throughout the class, opinion was split regarding translation according to option choice. Of those pupils who are continuing with Latin to GCSE, nine out of 11 said they enjoy or greatly enjoy translation in comparison with only two of the 13 pupils who are dropping Latin. A similar pattern emerged concerning pupils’ attitudes towards the CLC. All 11 pupils who have chosen Latin enjoyed or greatly enjoyed following the story of the CLC and ten showed positive feelings regarding discussing the stories of the CLC. Among those not continuing the subject the reaction was more divided.

This difference of opinion was reflected in the interviews. One pupil commented that ‘Even though the translating's really important … it get tedious after a while’ (Pupil F); whilst others were more explicitly negative: ‘The worst bit's … probably the translation’ (Pupil I) and ‘I don't really like translation’ (Pupil D). Pupil F's comment here is perhaps most interesting. This pupil recognises the value of the activity; however, it is their complaint is that the activity can be used too frequently. This desire for and appreciation of a variety of activities was one of the most frequent themes emerging from the group interviews. When asked what they would like to do more of in lessons, one group responded:

Pupil E: Doing more activities based around it like the plays and the poems.

Pupil F: Yeah. Sort of group activities with sort of competition and stuff are fun.

Furthermore, in three of the group interviews, the use of plays and roleplay was identified as one of the learning activities that pupils enjoyed the most. Interestingly, pupils did not just seem to like these activities because they found them more enjoyable. One pupil explained that ‘When we do stuff like little roleplays … you do get it in your head more’ (Pupil C). This suggests that, for pupils, variety of activity is not only appreciated because it is more fun to be acting than translating Latin, but also because it makes the learning process easier. Interestingly, Pupil C made further comment about the benefits of roleplay activities: ‘When we do things like that I remember it … I remember about the Egyptian slave boy … but I don't remember about the story that we translated last week’. This comment seems to suggest that the pupil primarily sees these activities as beneficial to their retention of the plot of the CLC, rather than their learning of the Latin language (vocab, grammar etc.). This, in conjunction with the indication in the questionnaire that pupils prefer translation and following the stories of the CLC to grammar and vocab learning, perhaps offers insight into how pupils conceive Latin. Whilst teachers, concerned with providing pupils with the tools so that they can succeed in exams further down the line, may concentrate on grammar and vocab learning, pupils’ interests and understanding of what the main aims of the subject are may differ, focusing more on following the story.

Conclusion

This case study provides some insight into the experiences of pupils studying Latin in a modern classroom, how they perceive the subject and what shapes their decisions regarding whether or not to continue with it. Pupils’ responses consistently demonstrated that they consider Latin a difficult subject and this difficulty was generally associated with the linguistic elements of the subject, particularly grammar. In this respect, pupils seemed to perceive Latin similarly to the way that Fisher (Reference Fisher2001) suggests pupils perceived MFL. Furthermore, this perception of Latin as a difficult subject seemed to have some bearing on pupils’ decisions concerning whether or not to take the subject. Perhaps as was to be expected, some pupils said that the difficulty of the subject was the/a major reason that they had chosen not to continue with the subject; however, for others, the perceived ‘challenge’ was a major appeal. This is again consistent with the findings of Fisher's (Reference Fisher2001) research in that pupil confidence in the subject (as opposed to whether they merely think it is hard or not) is a crucial factor in whether pupils continue with the subject or not.

Nonetheless, throughout the class’ responses we see the implication that Latin retains an image of being particularly academically challenging and, indeed, one pupil more explicitly voiced the suggestion that Latin is an intellectually elitist subject (‘It's more for the clever people’). Even among those pupils studying the subject, Latin is not yet apparently free from associations of elitism, despite the attempts of the CSCP to provide a course which is inclusive.

The study provided mixed responses from pupils concerning their perceptions of the relevance of the subject; however, the class certainly did not seem to see Latin as irrelevant. What was clear was that pupils’ understanding of the relevance of a subject (or at least Latin) is closely linked to their view of its instrumental value. Whilst many pupils did see instrumental value in Latin based on its beneficial impact on other subjects and, in one case, on the grounds that it worked the mind, I am personally of the view (articulated by Bolgar, Reference Bolgar1963, pp. 5–26) that the study of Latin should not be justified based on these utilitarian grounds. Among those pupils dropping Latin, their perceptions of the relevance of the subject did not have as clear an impact on their choices as their perception of the difficulty of the subject. I would argue that this potentially serves as a reminder to teachers regarding the priorities of pupils at this stage in their educational career. Whilst those involved in the teaching of the subject may be at times preoccupied with questions regarding the place and relevance of Latin in schools, it is not necessarily true that this is pupils’ first thought when thinking about their subject. Indeed, endeavouring to ensure pupils perceive Latin as something engaging and enjoyable may be more important in terms of recruitment than ensuring they see the subject as relevant.

The case study also implies the importance of varied and engaging teaching methods. Pupils suggest that this is important not only in order for lessons to be enjoyable, but also in order that they retain what they have covered (at least in terms of the plot). Even though pupils’ responses implied that the benefits of varied activities were primarily in terms of following the plot of the CLC, this is not to say they are of no value to the acquisition and retention of linguistic understanding. Because of the nature of the CLC (a reading course which gradually and inductively introduces new linguistic features), it is important that pupils remain engaged in and motivated by the plot. The variety provided in the course through the paralinguistic material was also commented on favourably by pupils, with the implication that pupils are interested in and motivated by finding out about the Classical world. It appears that the CSCP's aim that the story of the CLC should provide motivation is indeed a sensible one, as indeed is their advice that ‘Translation is a most useful learning and testing device, but it is not all important and sometimes can be dispensed with’ (CSCP, 2016b).

Implications for practice

I would argue that this case study raises certain questions about the way Latin is taught using the CLC. In particular, I would argue that the perceived difficulty of the subject is something that merits consideration. If Latin is to shake off the associations of elitism and present itself as a fully inclusive option in schools, it will need to address the idea that it is unusually difficult. Whilst it seems that pupils find all language learning in schools particularly difficult (as illustrated by the research into perceptions of MFL), Latin may make itself more vulnerable if it is seen as too difficult because it lacks the extrinsic motivation of MFL; pupils may persevere with MFL because the outcome will be a skill of utilitarian value, unlike in Latin. However, we should equally be aware that the unusual identity of Latin as a subject that is particularly challenging is one of the most appealing factors for some pupils, particularly those who are more able. While it may be tempting to suggest that it is on this ‘target audience’ that Latin should focus, this would be to fundamentally fail to address the issue of inclusivity and to fail to take responsibility for educating all pupils, as other subjects (such as English and Maths) are forced to. Although responsibility rests with teachers to ensure that Latin is not seen as too difficult, it should also be recognised that teachers are faced with the pressure of preparing pupils for GCSE exams in future years and, as a result, feel compelled to move at a certain pace.

This case study also demonstrates the importance of teachers endeavouring to introduce variety into their lessons. Not only do we see that different elements of studying the CLC (translation, comprehension of the stories, the paralinguistic material) appeal differently to different pupils, we have also seen that pupils think monotony hinders their retention of what they have learnt. I would argue that, if teachers are to use the CLC, it is important that they endeavour to follow the principles and advice which the CSCP offers to teachers. Given that pupils do not necessarily perceive the understanding of grammar rules as the outcome of Latin lessons, it is crucial that teachers pay due attention to the plot of the CLC and allow this to provide the intrinsic motivation for study of the language.

In terms of pupils’ comments on the relevance of the subject, I would argue that, at least for the class in question, this represents less of a significant issue than might have been expected. Indeed, many perceived Latin as having instrumental benefit based on its relationship to other subjects. As a result, I would suggest that Latin teachers should perhaps not be overly preoccupied with questions of the relevance of the subject. Given that pupils did demonstrate a clear interest in ‘finding out about the Romans’, I would argue that teachers’ attention should be devoted primarily to satisfying this curiosity, whether teaching through Latin or paralinguistic material in English.

Finally, I would argue that, for teachers, the most interesting thing that emerges with regard to the reasons that pupils either elect to continue with or drop Latin, is that pupils in the class in question were apparently more influenced by their experiences of studying the subject rather than their broader perceptions of the subject, particularly with regards to its relevance. Again, I would argue that the primary implication here for teachers is that, in order to encourage pupils to continue studying Latin, it is crucial that they are provided with an engaging and inclusive learning experience.

Appendix 1: Latin Questionnaire

Please answer the following questions honestly. There are no right or wrong answers. Your responses will be made anonymous

Appendix 2: Results to questionnaire

Appendix 3: Extracts from Interview 1

Interviewer: Which bits are the best and the worst?

Pupil D: I don't really like translations because I don't think they get it … like words don't get in my head that way.

[…]

Pupil C: I liked it when we did, like, roleplays. When we do things like that I remember it … I remember about the Egyptian slave boy … but I don't remember about the story that we translated last week’

Interviewer: So, do you think Latin is relevant?

Pupil B: Yeah. I think I have a better understanding of English

[…]

Pupil A: I think it's relevant in different ways, like, 50/ 50 with it, because it is relevant because obviously we've got our language from it, but in other ways I don't think it's relevant because we don't speak it- I'm not going to go up to someone, like, ‘Hey’ in Latin, obviously.

Appendix 4 : Extracts from Interview 2

Interviewer: Do you enjoy Latin

Pupil E: Yeah. It challenges me more than other subjects.

Pupil F: Yeah.

Interviewer: So, you think it's more difficult than other subjects?

Pupil F: Yeah, but in a good way. It's more challenging, not more difficult

Interviewer: You've all picked [Latin] for GCSE. Why have you picked it?

Pupil F: I wanted to do a language and I just enjoy doing Latin.

Pupil G: I picked it because of the challenge inside of it […] This was so my brain could be tested.

Interviewer: Do you think it is a relevant subject?

Pupil F: I think it is relevant because it helps sort of keep your brain working.

Pupil G: I wouldn't say it's as relevant [as MFL] … because … [with MFL] you can go out and go to that country.

Pupil H: I think it makes learning modern languages easier in some ways because they all stemmed from Latin

Interviewer: Is there anything you'd like to do more or less of in Latin lessons?

Pupil E: Doing more activities based around it like the plays and the poems.

Pupil F: Yeah. Sort of group activities with sort of competition and stuff are fun.

[…]

Pupil F: I think, like, for me, even though the translating's really important … it get tedious after a while.

Appendix 5: Extracts from Interview 3

Interviewer: Do you enjoy Latin overall

Pupil I: A bit. I enjoyed it more at the start of the year but as it's got more difficult. I don't really enjoy it now.

[…]

I know … it should be hard, but it's really difficult. There's so many different cases and tenses and I'm just so confused now.

Interviewer: So, what do you think are the best and worst bits of learning Latin?

Pupil I: We used to do plays and stuff. I like learning about the background of Latin, like the historical bit. And the worst bit's, like, probably the translation.

Interviewer: Do you think Latin is a relevant subject?

Pupil I: […] most people say it's a dead language now, so I don't know what it would help me with personally.

Interviewer: Do you have any other ideas about what Latin is? You talked earlier about it being a dead language…

Pupil I: […] When you tell other people that you've picked Latin they go ‘What've you picked that for?’ but, like, when you actually do it, it's quite interesting.

Pupil J: Our school motto is in Latin so most people don't understand it unless you explain it to them. And, like, most posh stuff is Latin.

Interviewer: So, Latin is quite a posh subject?

Pupil I: Well, I think it's more for like the clever people, like the brighter people.

Appendix 6: Extracts from Interview 4

Interviewer: What bits of Latin lessons do you like best?

Pupil L: […] What we did the other day and we were acting. We understood the whole story just because other people did different things. And acting. I like acting. I find it funny.

Pupil O: I quite like the background information … you're learning a bit about what it was like back for people living back then. I find it a bit different to the other lessons.

Interviewer: Are there any bits [of learning Latin] you particularly don't like?

Pupil M: Vocab.

Pupil L: I don't like learning grammar because I just forget everything.

Pupil K: It's easy to translate it but it's when you're asked to put it in like what case it's in and stuff, that's hard.

Pupil O: Yeah. When it comes to just learning grammar by itself it can be harder but when it comes to putting it into the translation it feels more natural.

Interviewer: Do you think Latin is a relevant subject for people to do in schools?

Pupil L: Yeah.

Pupil K: I can understand why it's a subject because it helps you with other subjects.

[…]

Pupil L: I think as well it can help a lot with other languages. So, lots of people say it's a pointless language – I don't think so.

Pupil K: Like people who do German and stuff say ‘Why do you do Latin? Why do you do Latin?’ but, like, we're saying why do you do German. Latin's fun.