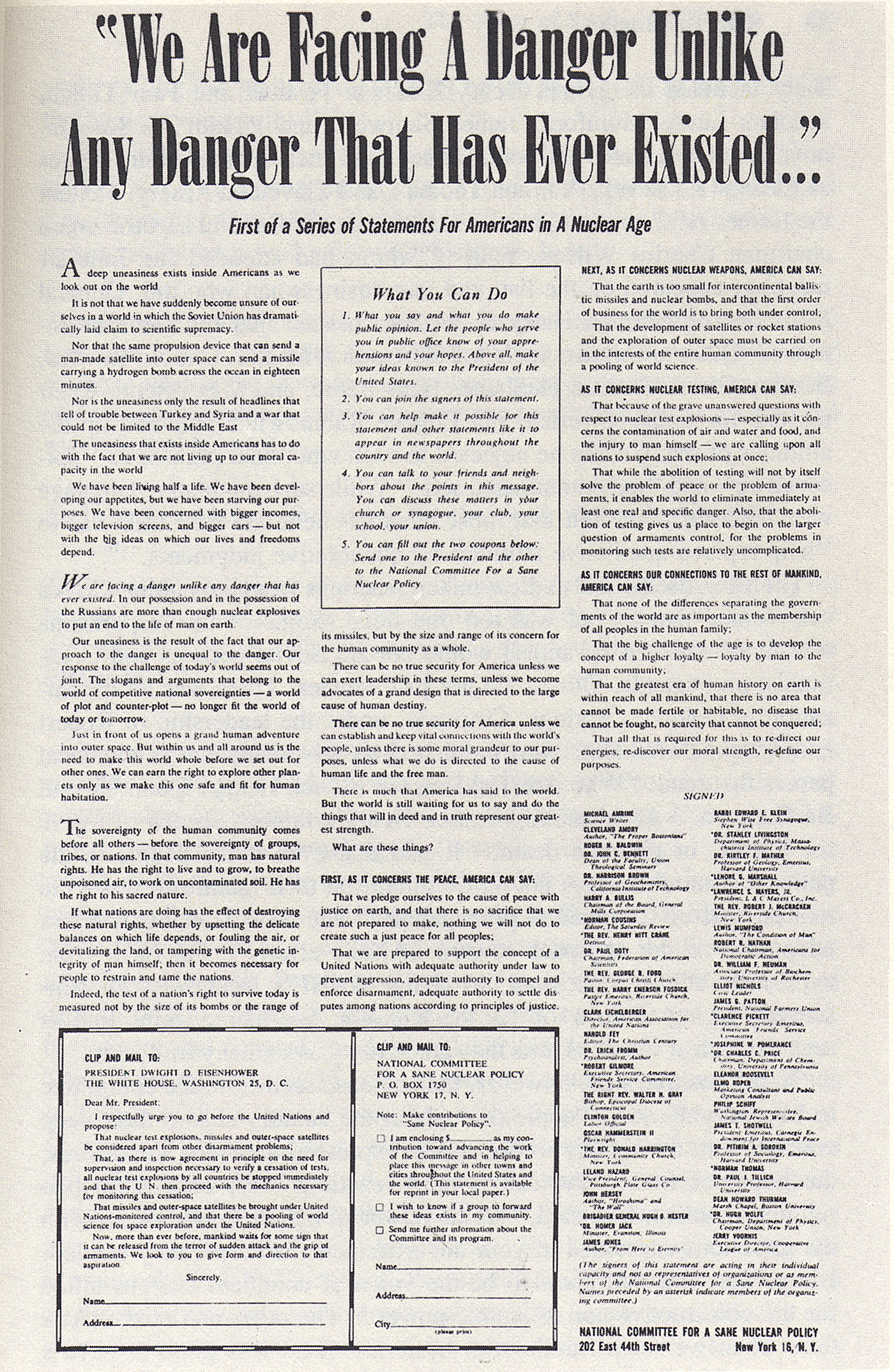

In 1957, SANE, the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, announced its founding with a full-page advertisement in the New York Times. “We Are Facing A Danger Unlike Any Danger That Has Ever Existed,” the notice warned, due to the ongoing “contamination of air and water and food, and the injury to man himself” caused by nuclear testing (Figure 1). Hoping to build a national movement, SANE hired a communication consultant to evaluate the ad's effectiveness. He concluded that it was “too long and too wordy,” arguing “that a photo or graphic symbol would attract the attention of the general public.” Indeed, SANE's first foray into the realm of mass communication was completely devoid of images. Lengthy text crowded the page. Even avid readers of the Times, the consultant explained, “had ‘missed’ the ad”—had not even noticed it was there.Footnote 1

Figure 1. “We Are Facing a Danger.” SANE advertisement, 1957. Courtesy of SANE Inc. Records, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

For historians of the modern United States, this episode, together with SANE's subsequent use of images, raises important questions about how the visual media have helped popularize environmental concern. From the fear of radioactive fallout during the Cold War to global warming today, images have brought environmentalism into American public life. Pictures—despite how they are typically treated by historians—do not simply reflect some pre-existing, external reality; they do not merely act as passive mirrors to events taking place outside the frame. Images instead serve as active rhetorical agents that shape larger cultural and political fields.

Images stir up audience emotions. They provoke anxiety and fear; they instill guilt and responsibility; they inspire hope and prescribe action. Recognizing the emotional power of images is key to understanding why the visual media became a vital player in environmental politics. By making Americans care, images have both advanced and hindered the environmental cause. They have promoted environmental values. And yet in the process, they have frequently distorted the ideas of environmentalists, portraying the movement as nothing more than a green consumerist crusade to absolve the nation of its guilt.Footnote 2

In their campaigns against nuclear testing, SANE leaders soon learned that success in the public sphere required more than text-based appeals. Fusing facts with feelings, reason with emotion, they began to use images to challenge the Cold War system of emotion management and the spectator democracy fostered by iconic photographs of the mushroom cloud. Following the advice of activists and advertisers, SANE eventually hit upon a visual strategy: the group sought to overcome the spectacle of the bomb blast through the counterspectacle of innocent children—to picture the nation's youngest citizens as biological subjects whose bodies and futures were threatened by fallout. SANE matched images with texts to depict long-term dangers—to explain how strontium-90 could enter the food chain and imperil human health. The group's most influential and widely circulated advertisement featured Dr. Benjamin Spock, the respected child expert (Figure 2). A photograph of the pediatrician with a toddler dominates the ad space. “Dr. Spock is worried,” the caption proclaimed. Brooding over the dangers of fallout, Spock appears unsure how to protect the child. “I am worried,” Spock explained. “As the tests multiply, so will the damage to children.” Many people wrote letters to praise the group for this ad, including one who observed: “The Dr. Spock advertisement is the greatest SANE has ever published. It represents a sure-fire way of reaching people who would otherwise not be touched by even the most logical approach.”Footnote 3

Figure 2. “Dr. Spock is worried.” SANE advertisement, 1962. Courtesy of SANE Inc. Records, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

While SANE sought to depict the long-term, accretive risks of radiation, other activists took advantage of the media's focus on sudden violence and immediate danger. By harnessing the power of media spectacle, they garnered mainstream attention and encouraged audiences to care about environmental devastation. In the 1970s, Greenpeace made its anti-whaling crusade highly visible through the circulation of carefully choreographed images of activists confronting Soviet whaling ships off the California coast. When these images were broadcast on national TV news and other media outlets, they triggered an outburst of public emotion, generating widespread concern about the plight of whales. In this case, media spectacle lent legitimacy to the environmental cause.Footnote 4

During oil spills and other moments of crisis, the visual media have made caring about the environment an easy—some might say too easy—thing for Americans to do. Spectacular catastrophes, such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, led to emotion-saturated media coverage: newspapers, magazines, and TV screens filled with pictures of oil-soaked otters and birds—poignant images of innocent wildlife suffering and dying. Corporate officials, sometimes joined by conservative commentators, charged the mainstream media with focusing too much attention on such disasters and duping the public into accepting the alarmist claims of environmentalists. Yet some environmental thinkers argued instead that the media fixation on sudden catastrophe made it more difficult to foster public understanding of slow-motion calamities like climate change. “When you look at pictures from Alaska,” Bill McKibben argued a few months after Exxon Valdez, “remember this: The ship that is our planet has a gaping hole in its side, too, and carbon dioxide is pouring out.” Images attracted momentary public attention and elicited outbursts of audience emotion. But could they help Americans imagine and create a sustainable future over the long term?Footnote 5

Images exert material and political effects on the world. From the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty and the flurry of legislative activity that accompanied the first Earth Day in 1970 to the banning of specific pesticides, the increasing public distrust of nuclear power, and the dramatic expansion of recycling programs nationwide, pictures helped spark environmental change. Yet too often popular images propose quick fixes and promulgate consumer fantasies of environmental hope. Like activists involved in civil rights, feminism, and other social movements, environmentalists have found that the visual media offer a double-edged sword. Pictures helped them bring their ideas into the mainstream, but they often elide, marginalize, or even denigrate their more far-reaching proposals for change.Footnote 6

The producers of popular environmental images have often obscured race, class, and other inequalities, foregrounding middle- and upper-class whites as the prime victims of environmental problems and the central subjects of the environmental cause. SANE's Dr. Spock ad, like others, sold environmentalism in this way, centering on the figure of the innocent white child as an emotional emblem of ecological risk. Throughout the history of modern environmentalism, this widespread emphasis on white children has worked to create a picture of universal victimhood, portraying all Americans, no matter where they live, no matter their race or class, as equally vulnerable to environmental dangers. From pictures of white women and children wearing gas masks around the first Earth Day to more recent campaigns, white bodies have often stood in for the nation, signifying the idea of universal vulnerability. These images have nurtured support for environmental protection, but at the same time have masked the ways in which pollution and other hazards have impacted some groups far more than others.

Beginning with the first Earth Day, mass media outlets have also frequently emphasized the notion of individual responsibility, suggesting that all Americans were equally culpable for causing the environmental crisis. Environmental activists have urged Americans to adopt more ecologically responsible actions; they wanted individuals to understand how their daily lives and consumer decisions were enmeshed in larger ecological systems. Yet many of these same activists became enraged when they realized that the media embrace of individual action let corporations off the hook. They rejected the message of the popular cartoon character Pogo the Possum, who declared in an Earth Day poster, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” They castigated the Crying Indian, who appeared in a 1971 anti-litter public service announcement sponsored by beverage and packaging corporations—a campaign that blamed individuals for ruining the environment and deflected attention away from industry practices. Many activists argued that the discourse of individual guilt shielded corporate polluters from scrutiny and shifted environmentalism from the political to the personal.Footnote 7

Amid the triumph of neoliberalism in recent decades, this lopsided faith in individual responsibility has dominated popular portrayals of the movement. The media and corporations have framed environmentalism as a form of therapy—a way to cope with the distressing news of environmental crisis. The plastics industry has proven particularly adept at manipulating consumer desire by exploiting images of sustainability to shore up an unsustainable agenda. In the late 1980s, the industry altered the original recycling logo—developed in the aftermath of Earth Day 1970—by placing numerals representing different grades of plastic in the center of the symbol (Figures 3 and 4). Even though the rates of plastics recycling never came close to keeping pace with the manufacture of new plastics, the recycling logo signified environmental hope. The logo proclaimed that the ravenous use of resources could continue: as long as consumers remembered to close the recycling loop, the three chasing arrows would cycle on and on. This popular environmental icon thus helped legitimate the continued expansion of plastics production.Footnote 8

Figure 3. Recycling logo prototype by Gary Anderson, 1970.

Figure 4. Recycling logos with resin identification codes, developed in 1988 by the Society of the Plastics Industry.

By encouraging Americans to shop their way to ecological salvation, media images have promoted short-term, consumerist solutions to long-term, systemic problems. In an age marked by rising rates of economic inequality, green consumerism catered to the affluent and obscured power relations. The assault on the ecosphere continued; the release of greenhouse gas emissions escalated; the poor and racial minorities experienced higher levels of ecological risk. All of this happened while recycling programs expanded across the United States, while green consumer products promised to shelter the affluent from harm, and while other individual lifestyle changes addressed powerful consumer desires for ecological redemption.Footnote 9

The challenge for many environmentalists, therefore, has been to move beyond the media's emphasis on easily digestible images of short-term disaster and therapeutic framings of environmental hope. In recent years, 350.org—a climate activist group co-founded by Bill McKibben—has turned to social media and YouTube videos to depict the escalating danger of climate change. Rather than urging consumers to change their light bulbs, 350.org envisions environmentalism as a collective effort to challenge the power of the fossil fuel industry and reimagine the future.Footnote 10

Understanding the remarkable durability of certain environmental issues—and the lack of traction of others—requires looking closely at the kind of work iconic images can and cannot do. But it also requires paying attention to the circulation of non-iconic images that have nurtured support for letter-writing campaigns and other forms of political action. Consider the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a remote area in northeastern Alaska that has become the most high-profile, frequently recurring public land debate in modern U.S. history. Pitting environmental and Indigenous activists against proponents of oil drilling, this struggle has been waged on Capitol Hill and across the national media landscape. Yet beyond the beltway and beyond mainstream channels of communication, activists have cultivated long-term support for refuge protection through traveling slide shows and other forms of grassroots outreach. These images helped create an alternative vision of environmentalism: an environmentalism that combines wilderness preservation with social justice, that merges human rights with the more-than-human world, and that sees the refuge as entangled with broader questions of sustainability and survival. In Arctic Refuge campaigns and in many other struggles, grassroots forms of image circulation mobilized public feelings, encouraged audiences to become political agents, and challenged mainstream views of the environmental cause.Footnote 11

The history of environmentalism is often told as a story of legislative battles or protest actions or scientific writings. But it is also a story of how images, emotions, and politics became interwoven in the modern United States. Pictures made it easier to sell certain forms of environmental protection: they created visual symbols for problems that could not be seen; they elicited concern for the well-being of innocent children and threatened species; they made viewers feel connected to distant places. Producers of popular images, though, narrowed the scope of the environmental cause: they downplayed social and ecological inequities; they overemphasized individual responsibility; they peddled green consumerist nostrums that made shopping seem synonymous with politics. Images provide portals into the achievements and failures of American environmentalism; they reveal the constraints of the past and conjure glimpses of other historical possibilities.