This study widens the historical perspectives of how a firm coordinates its activities to simultaneously achieve financial and political ends while using regional efforts to enact a national strategy. We explore the use of marketing and public relations in the context of the shareholder democracy movement of the 1920s by investigating Bell Telephone Securities (BTS), a transitional subsidiary of American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T). Footnote 1 We emphasize that corporate sponsorship was conditioned by the complementary objectives of exploiting economies from stock price support activities through strengthened financial market operating capabilities and the creation of a national political constituency. These objectives existed at the national level but needed to be realized regionally. As the largest publicly held corporation of its time, as well as the U.S. corporation with the broadest geographic spread, analysis of the activities of the Bell System gives insight into how U.S. corporations responded to the economic, political, and social challenges they faced. This has led, for example, to Roland Marchand’s focus on AT&T when discussing the changing role of advertising and public relations for firms in the early twentieth century, as well as its inclusion by Julia Ott in her broad survey of the shareholder democracy movement. Footnote 2 Similarly, our work uses AT&T as a model to explore the coordination of management’s financing and political strategies in a national firm with largely regional operations.

Richard John’s history of American telecommunications, while not expressly discussing investor democracy, does help to further understand the milieu surrounding BTS’s emergence by examining the cultural and political environments in which the investor democracy movement flourished. Footnote 3 Christopher Jones has noted that America’s transformation from an organic to mineral energy regime was a self-reinforcing process, actively guided by corporate management, Footnote 4 and echoes of this story can be detected in the growth of AT&T. Like the change from reliance on wood to reliance on an electrical power grid, the dominance of the telephone as a communication device built on structures developed by earlier technologies, primarily the telegraph and postal services. Corporations promoted to the public the advantages of each new innovation. An innovation’s technological advantages encouraged its adoption, which lowered its costs, leading to even wider usage. While beneficial to American society as a whole, the costs and benefits of the telephone, like the costs and benefits of the power generation, were unevenly distributed. In both cases, the main beneficiaries were urban centers and their suburban peripheries; rural areas benefitted far less. This pattern encouraged local opposition, which corporate interests needed to counter. By expanding corporate ownership to large numbers of average Americans, corporate interests sought to dampen or counter this local opposition.

As with other monopolistic enterprises in railroading and electrical power generation, the Bell System was deeply influenced by regional business dynamics. During its earliest years, the firm relied heavily on funds raised through locally franchised affiliates to finance the build-out of the network. Later, the parent company adopted a holding company structure that coordinated its activities, with the exception of long-distance services via more than a dozen of what would eventually be termed “regional Bell operating companies,” or RBOCs in telephone-speak. Bell had extensive regional governmental exposure. It was in constant need of municipal construction variances, licenses, and rights of way. In addition, states were the sites of incorporation and shared oversight responsibility with two federal agencies: the Interstate Commerce Commission and, later, the Federal Communications Commission. Competition with the thousands of small independent telephone companies across all regions after the expiration of Alexander Graham Bell’s patents in 1894–1895 led in 1913 to a broad agreement that compelled the company to curtail its horizontal expansion and open access to its long-distance grid to qualified local rivals. From a managerial perspective, there was also a push of national headquarters administrative practices into the regional units. A central statistical department, for example, served as a model for the subsequent formation of such capacities among the RBOCs. Most important, however, was how the new form of voice communication increased the efficiency of regional business by enhancing the ability to transfer ideas, coordinate action, and interact with a growing number of points of economic contact, all of which served Bell’s fast-growing network. Footnote 5 Indeed, the success of Bell’s efforts to integrate regional operations within a national framework demonstrates the firm to be an exception to the contention that regional disparities within the United States led to business disorganization. Footnote 6

Bell System historiography has generally taken one of two lines of research—the first relating to the firm’s involvement in the political economy, Footnote 7 and the second to its sociocultural initiatives. Footnote 8 Integrating the study of investor democracy extends scholars’ understanding by explaining how programs designed both to improve the image of the heavily regulated firm as a positive economic force and good corporate citizen and to broaden share ownership among small investors helped to defuse potential public opposition to its plans and policies. Bell, and other sponsors of broader public ownership, sought to surmount both a Progressive legacy of distrust that persisted in some circles about the economic and political power of giant business enterprise as well as the rejection of capitalism by more radical elements. By facilitating thrift and wealth-building through share purchases, the firm sought to extend the belief that such investment was an extension of traditional, republican American values. As recounted by Jonathan Levy, Americans’ concepts of both security and democratic participation evolved in response to changes in American society over the nineteenth century. Footnote 9 Reliance on a family farm for economic support faded as more people became wageworkers. At the same time, the idea of preparing for financial adversity—earlier feared through catastrophic weather events, then through loss of a job or a worker’s ability to work—became envisioned as a responsibility that workers could meet through insurance, savings, and investing. It was at this juncture of changing notions about investing and democratic participation that Bell management sought to build a constituency of small shareholders, enacting a national strategy through local operations.

Adopting one of these two broad perspectives largely overlooks the strong penchant of Bell management to structure their commitments in ways that simultaneously achieved several complementary objectives. Although this type of operational multiplexing was deeply embedded in the Bell’s organizational DNA, it is a pattern that remains largely unexplored in the large corpus of earlier studies dealing with firm management. Footnote 10 The basic structure of Bell perforce evinces its adherence to the notion of integrating complementary operations. The AT&T holding company had grown strong through a structure that allowed the high-level coordination policies among its many regional operating subsidiaries—which allowed the firm to customize its services to local requirements—and Long Lines, its Western Electric manufacturing unit, and Bell Telephone Research Laboratories.

Importantly, by the 1920s, the identification and prioritization of challenges—as well as planned responses—for the Bell System as a whole came from the top. A degree of uniformity in prioritizing and then addressing problems enhanced the ability of management to plan and monitor operations. Such standardization was demonstrated in the firm’s dissemination of mandatory procedures for plant maintenance, traffic management, inventory control, construction, and human resources. Footnote 11 The difficult, and more complex, handling of rights offerings remained centralized, largely in the hands of New York corporate personnel. However, while AT&T’s management recognized challenges common to the entire system, it also saw that regional variations existed that would require differences in approach. Enlisting local Bell personnel in recruiting customer-shareholders allowed BTS to use the subsidiaries to target regional audiences for its financing efforts.

In the case of BTS, five interconnected objectives defined its operational scope. The first involved the build-up of political leverage by increasing the numbers of shareowners as a potential counter to the heavy firm regulation at all levels of government. The second concerned responsiveness to the social and cultural milieus by building, through advertising, education, and public relations, investor identification with the firm and its espousal of democratic and capitalistic values. The third related to the development of new capacities to attract equity funding capital from previously untapped sources to support the rapid growth of the firm during the 1920s. The fourth pertained to the establishment of new means for stabilizing prices and maintaining stock market liquidity of Bell shares, particularly in support of periodic rights offerings, and debt conversions that increased the number of shareholders and increased equity, the largest portion of Bell’s long-term capitalization. Footnote 12 Fifth, its sale of unexercised rights also helped to lower the overall cost of equity capital. These practices eventually ended with the disbanding of the subsidiary when its defining policies became unsustainable because of the radical socioeconomic and regulatory changes brought on by the Great Depression, but by this time many of its original objectives had been realized.

The Bell System leadership defined BTS’s objectives in ways that sought to bolster the operational sustainability of the national telephone enterprise in the face of several challenges during a dynamic period in U.S. business history. The first was financial. AT&T, the world’s largest publicly held company, needed to attract sufficient funding to support the rapid expansion of its capital-intensive enterprise without incurring excessive levels of financial risk that might threaten the operation of its telephone network during periods of crises. The second related to the need to enhance managerial capacities for planning, coordinating, and controlling business activities of great scale, scope, and complexity. A third challenge involved responding to increasing regulatory oversight and political forces that constrained the power of the communications leviathan. Last, management endeavored to create a positive public image for the firm in an environment in which many concerns were voiced about the dangers of concentrated economic power to social equity and republican democracy. While these challenges did not originate in the 1920s, they gained sharp focus as the nation’s attention turned homeward with the conclusion of World War I.

The Bell System’s financial challenges were similar to those encountered by the monopolistic units that had come to dominate capital-intensive railroad, electrical utility, and communications industries early in the twentieth century. Footnote 13 Unlike the manufacturing sector, in which giants like Standard Oil, DuPont, and General Electric had financed their respective growth largely from retained earnings, the utilities depended to a much greater extent on debt to build and maintain their extensive national or regional systems. Theoretically, these companies should have been able to safely borrow more than manufacturers because of their strong market power; however, the risks of excessive leverage constrained their borrowing. To raise debt capital, they relied heavily on investment banking firms, such as the House of Morgan (in New York) or Kidder, Peabody (in Boston). Footnote 14 Bankers placed most of these issues with insurance and trust companies or wealthy individuals in the United States and abroad. Despite market dominance, however, too much debt leverage could lead to financial disaster, as evinced by the extensive insolvencies among railroads during the financial crises of the 1870s and 1890s.

Raising equity capital also had its challenges. Investors had long considered equity investments to be speculative in part because of weaker property rights with respect to claims on income via dividends and on assets in the event of business dissolution. Moreover, unlike bond contracts, which provided precise information about returns, duration, and collateral useful in valuation, few companies provided the operational data that was necessary for projecting future profits and dividends.

The Bell System sought to diminish risk perceptions associated with the asymmetries that separated investors from their corporate agents by providing highly detailed annual reports. Additionally, in 1913, the firm began filing standardized financial statements with its national regulator, the Interstate Commerce Commission. Nevertheless, the firm operated in a context in which stock market investing was viewed by many as hazardous and akin to gambling. Speculation based on rumors and other unsubstantiated claims provided grist for marginal “bucket shops” that were essentially unregulated betting parlors. Security prices could be manipulated on exchanges through the concerted trading power of “pools” that overwhelmed transacting for particular shares. A significant incidence of fraud in securities dealing induced many states to promulgate “blue sky laws,” which sought to ensure probity by registering brokers and controlling the flotation of new issues. Footnote 15

Despite this history, in the early years of the twentieth century, equity markets began to strengthen and the number of investors expanded to meet the growing number of issuers. Footnote 16 The success of the wartime Liberty and Victory Loan drives evinced the tremendous potential for raising capital from large populations of small investors. The Merrill Lynch partnership, first formed in 1915, began building a pioneering national retail brokerage chain that, unlike the bucket shops, was differentiated by its professional advisory and planning services. Merrill Lynch recognized the middle class to be a huge, untapped capital market. Footnote 17 Interest also grew in closed end mutual funds, which had existed in the United States since the 1890s. Footnote 18 During the 1920s, firms such as Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers began to specialize in the floatation of equity issues. Footnote 19 Capital-hungry utilities explored new modes of finance. As early as 1914, Pacific Gas and Electric sold shares directly to customers, partly as a means to counter the growth of a public ownership movement in its territory. Other utilities, including Public Service Corporation, the United Corporation, and Insull Utilities Investment Management, among others, pyramided investment through complex holding company arrangements to maximize opportunities for selling equity from component companies and to leverage earnings. Footnote 20

The Bell System, however, was an outlier with respect to these general trends because of its relatively heavy reliance on equity over debt finance. From its founding in 1877, the firm had historically maintained low levels of debt leverage. The financial conservatism of the company’s leadership doubtless also reflected sensitivity to the need to minimize all types of risk, both financial and operational, which could threaten the smooth functioning of their complex telecommunication system. The reliance of equity over debt to finance the firm’s capital investments is show in figure 1. For example, in 1900, only 8 percent of the firm’s $122 million in assets was financed by long-term debt. Footnote 21

Figure 1 Bell System fixed assets and long-term debt, 1900–1927.

Source: AT&T, Annual Report of the Directors of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, 1927.

The market operations of BTS and the employee stock purchase plan helped to enhance financial efficiency. They facilitated the growth of equity capital though preemptive rights offerings and through the conversion of debt to equity. Their market price support activities also contributed to the lowering of the 9 percent cost of equity capital based on the par value of its shares. This came about from the issuance of shares at steep premiums over par in the conversion of debt and in the sale by BTS of unexercised preemptive rights and of shares through installment financing. The effective rate of return fell in proportion to the increase over par in share issuances. Because of the extensive equity operations, the overall level of debt remained low. In 1916, for example, long-debt funded only 28 percent of the $722 million of assets, while capital stock and earned surplus accounted for 54 percent. Footnote 22 Reliance on equity as a capital source reinforced to management the importance of having stable stock prices, as the Bell treasury department’s programs increased total shares outstanding from 569,000 in 1900 to 18.7 million in 1930.

Another challenge to organizational sustainability arose from the difficulty of managing a giant, geographically extensive enterprise. Beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century, U.S. industry experienced major transformations as improvements in communications and transportation provided the basis for the emergence of an industrial–urban economy. Large companies, first in the railroads and then in manufacturing and public utilities, had to confront the problem of establishing managerial structures for planning, coordinating, and controlling business activities of great scale, scope, and complexity. Footnote 23 The Pennsylvania Railroad successfully experimented with a structure involving a line-and-staff dichotomy to manage its horizontal integration. The line organization was responsible for daily operations of the system, while the central staff had responsibility for planning and oversight. More elaborate structures emerged in this sector as enterprises such as the refiner Standard Oil vertically integrated backward to acquire control of raw materials and forward to guarantee direct access to consumer markets. Footnote 24 Explosives manufacturer DuPont diversified its product line to make use of underused resources, to reduce business risk, and to serve its new markets by establishing dedicated divisions or subsidiaries. Footnote 25

Like many nascent utilities, the Bell System operated through a holding company structure with a parent corporate entity: in this case, AT&T. This provided strategic and financial oversight to regional operating companies as well as direct customer service. The parent also controlled much of the system’s equipment requirements through its Western Electric subsidiary. Footnote 26 This structure initially operated very loosely, but central control through the parent increased greatly during the long presidency of Theodore N. Vail, starting in 1907. He introduced a “universal service” program that involved the standardization of technology and management practices. System monitoring and planning were strengthened through the proliferation of new sources of accounting, budgeting, and operating data. This enhanced the power of the center over the periphery and helped to ensure the same quality of service throughout the system. Footnote 27 One culmination of this penchant for centralization was the organization in 1925 of the Bell Telephone Laboratories subsidiary as the exclusive center for the firm’s research endeavors. Footnote 28

The firm also had to respond to the mandates of an emerging regulatory regime, as demand for regulation rose with the evolution of huge corporations. Bigness in business was deemed to involve a potential trade-off of democratic values for material abundance. Although many Americans wanted the improvements in living standards from industrialization, they feared the market and political power of giant enterprises. Footnote 29 As historians have noted, a major response to these developments in the United States was the establishment of new regulatory institutions and commissions that sought to control monopoly through administrative law. Footnote 30 Regulation provided countervailing power against dominant companies, and it also mediated the allocation of the returns to the monopoly franchise among investors in the form of higher dividends and stock prices and the general public in the form of more efficient and economical service.

Railroads were the first to experience such regulation. Massachusetts led the way in 1869 by mandating the filing of financial statements to provide greater transparency for investors. Footnote 31 In the following decade, because of the pressure of Grangers and other shipper groups, many states in the South and West sought to regulate the fairness of rates. Footnote 32 In 1887 Congress established federal capabilities for advancing these policies through the formation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which expanded its purview to the telephone industry in 1910 with the passage of the Mann–Elkins Act. Footnote 33 Beginning in 1908, state commissions for regulating telephone service largely displaced earlier municipal oversight, with such boards increasing steadily to forty-five by 1915. Footnote 34 The transfer of federal oversight authority from the ICC to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) during the New Deal in 1934 greatly expanded the scope and power of federal oversight.

After the Bell System reincorporated in New York in 1900, partly to avoid restrictive features in Massachusetts’ regulation, the firm successfully adjusted to the demands of both state and federal regulations through the Progressive era and the 1920s. The firm came to an agreement with the U.S. Justice Department in 1913 that enabled it to deflect anti-trust prosecution and to maintain its national system in return for an agreement to dissolve its controlling investment in Western Union Telegraph, to stop growing through acquisition of rival companies, and to provide independent telephone companies greater access to the Bell network. Footnote 35 The ICC’s monitoring was mild and accommodative, requiring, among other matters, that the firm develop and report using standardized financial statements and that it comply with the 1913 Valuation Act’s requirements to provide estimates of both of the original and replacement costs of physical plants and facilities. During the regime of President Theodore Vail, the firm followed an explicit policy of cooperating with state and municipal boards as long as their policies were “fair and reasonable.” Footnote 36 The importance of these governmental relationships was evinced by the formation in 1912 of a special bureau in the headquarter’s statistical department, a bureau that exclusively prepared monthly reports on all regulatory decisions throughout the United States. Footnote 37

New forces transforming the social landscape complicated the challenge of maintaining organizational sustainability. In the early twentieth century, America’s populace rapidly changed as the country became increasingly urbanized and ethnically diverse. Among American elites, however, there was a worry that the social and political fluxes experienced by several European nations might erupt in the United States. Footnote 38 This generation witnessed a successful Socialist revolution in Russia in 1917 and German upheaval in 1918–1919. The vying of Socialist, anarchist, and Labor candidates for elective office on the national as well as the state and local levels raised concerns about the preservation of property rights. In 1919 Bell’s New England Telephone subsidiary experienced a disruptive strike of its telephone operators for better working conditions, pay, and the right to organize, which started in Boston, the original city for the Bell System’s headquarters. This soon was followed by a disruptive Boston police strike, which induced Governor Calvin Coolidge to send in the National Guard to maintain public order. Footnote 39 The “Red Scare” of 1919–1920, highlighted by a violent attack on the home of the U.S. attorney general and bombings on Wall Street, four blocks from AT&T’s New York headquarters, led to mass deportations of immigrants suspected of being active in radical political movements. Footnote 40 Business and government leaders grappled with the appearance of homegrown Socialist movements, which sought to radicalize the working class. The concerns on the importation of radical beliefs that seemed contrary to traditional American values contributed to the imposition of a new immigration law that sharply curtailed the number of admissible immigrants from eastern and southern Europe.

It was in this context that the notion of investor, or industrial, democracy was born. Footnote 41 Industrial democracy envisioned replacing the equation of proprietary democracy, in existence since Jeffersonian times, with a democracy evinced by those claiming an ownership stake in American capitalism. Stock ownership began to widen among a larger investor base, and financial markets and institutions that were once considered elitist evolved into foundations of American capitalism. Proponents of investor democracy endeavored to align the American public’s social and economic interests with corporate enterprise by promoting broader public ownership of its investment securities. Widespread stock ownership would demonstrate broad public commitment to capitalistic institutions. Aligning corporate and public interests would also create an informal constituency that would be supportive of business-friendly legislation and policies. Investor democracy was expected to result in the formation of countervailing power by leading business enterprises against the new forces of government oversight and control. Recognizing that increased public ownership of corporations could answer several business needs, the business writer and equity promoter Edgar Smith noted that “the support of the public became increasingly of greater importance both financially and for protection against unwise legislation.” Footnote 42

For individual investors, participation in financial markets also had become an element for individual financial security. With wages providing more than subsistence living, Americans had funds available to prudently put aside for a rainy day. The entry of the United States into World War I, and the government’s decision to fund the war effort through issuing small denomination bonds, introduced many to their first experience of investing. Americans’ positive experience with the Liberty Bond campaigns proved the viability of raising huge amounts of capital from the growing working and middle classes. The industrial democracy movement was the next step in this process; now, instead of lending their support to the government, the public would be asked to support and identify with American business.

Ownership of shares also created a psychic association with the firm’s cultural image. By the 1920s, AT&T had established a powerful image of technological and scientific leadership in the high-growth field of telecommunications. Ownership of AT&T shares allowed shareholders to become partners in the advancement of science for the greater good. Moreover, the characterization of shares as being appropriate for widows and orphans signaled how a wealthy and beneficent mother—“Ma Bell”—could be enlisted to protect society’s most economically vulnerable. Cultivating such a public image helped counter the picture painted by Bell System critics who viewed the Bell Telephone System as grasping and dangerous to democracy. These perceptions were especially pernicious in rural areas in the South and West, where the independent telephone companies had historically been strong. Footnote 43

Although many corporations initiated stock ownership programs, it was especially important to AT&T. Bell Telephone Systems was designed to facilitate the average American’s purchase and holding of Bell System securities, especially in regions in which ownership of BTS shares was historically low. Using marketing and innovative sales plans, AT&T created a national constituency of shareholders, becoming the most widely held public company in the world. Through BTS and its employee stock ownership plan, the firm succeeded in creating the largest class of stockholders in the nation, reaching a high of 650,000 in 1935. Footnote 44

Purpose and Vision

The formation of BTS was planned in 1920, a year before its actual incorporation in Delaware in September 1921. President Harry B. Thayer (1919–1927) had a three-fold purpose in mind. Financially, AT&T wanted to raise $100 million in permanent capital to fund the Bell System’s growth during the 1920s. Second, firm management perceived a need to fund expansion by attracting capital from new investors beyond the bounds of the predominant shareowner territory of the Northeast. As Thayer explained to Robert Winsor, managing partner of Kidder, Peabody:

We have become so large that we can no longer depend for our constituency on any one section of the country or on any one class of investors, but on the contrary, we must have as far as we can get it the understanding of and confidence of in our concern of the whole investing public. Footnote 45

Concurrently, Thayer wanted to improve the image of the firm in the eyes of the public, especially prospective shareowners by offsetting “the misinformation which is and has been for some time in circulation regarding our affairs. Some of this is malicious but most of it is due to ignorance.” Footnote 46

Although Bell might have relied on the agency of brokerage houses such as Kidder, Peabody, it elected for several reasons to rely instead on firm personnel to undertake this task. Thayer believed that the educational component of the stock plan—defining the mechanics of exercising rights—and the provision of information about the firm and its mission could be better controlled by Bell than by an outside party. Additionally, commission brokerage chains were just beginning to emerge during this period and did not have a national reach; Kidder, Peabody, for example, was largely limited to Massachusetts. There was also a fear of sullying the firm’s image through misrepresentations made by unscrupulous brokers over whom Bell exercised little control. Furthermore, the rural clientele that the telephone giant desired to recruit often were situated in locales without access to brokerage services yet had local telephone company representatives. Finally, President Thayer anticipated an eventual need to sell preferred stocks in regional subsidiaries to local subscribers, which would be facilitated if Bell could make a market for these securities. Footnote 47

The first step in the process of internalizing the new finance function was to determine the legality of Bell’s involvement in a program for reacquiring and distributing its shares and the best organizational form to achieve this goal. In December 1920, after much internal discussion of this question, the firm’s legal staff recommended that either a subsidiary through Western Electric be formed for this purpose or that AT&T’s articles of incorporation be modified to allow the formation of a finance subsidiary. Footnote 48 The latter course of action was followed. Footnote 49 However, some of the legal staff continued to worry that such a subsidiary might be challenged legally. They thought that the corporate veil might be pierced on the grounds that the wholly owned subsidiary had been formed to conduct transactions that the parent was prohibited from undertaking, such as taking dividends or exercising stock rights and voting shares. Second, there was concern about adverse public reaction to corporate activity, which would raise share prices from the firm’s anticipated practice of open market purchases of its own shares. Footnote 50 The advisability of organizing this subsidiary in the light of these uncertainties would eventually enter the public discourse after the dissolution of Bell Telephone Securities in 1935.

In making this choice, Bell differentiated its organizational structure for share distribution from the pattern followed by many contemporaneous electrical power companies. These latter enterprises operated through securities holding companies, which were not directly engaged in power transmission and thus not subject to state regulatory supervision. This option was irrelevant to Bell because it was subject to federal supervision through the ICC. This oversight was particularly problematic because of the possibility that the contemporaneous empowerment of the ICC to regulate railroad finance, under the Transportation Act of 1920, might be extended to the telephone industry. A wholly owned, non-operating subsidiary dedicated to securities trading and distribution doubtless seemed effective in confronting this eventuality.

Other reasons existed for operating through the new subsidiary Bell Telephone Securities, a name suggested by its future president, Walter S. Gifford. Although AT&T, the parent company, could deal in Treasury shares, accounting for Treasury transactions resulted in direct adjustment of the firm’s permanent capital rather than as profits because AT&T was prohibited by corporate law from earning a profit in dealing in its own shares. However, the BTS subsidiary could record these transactions on its books as gains or losses, and thus qualify these items for inclusion in AT&T’s consolidated income statement. Footnote 51

Equally important, but not explicitly acknowledged by Bell management, was the stock price stabilization effects that resulted from BTS’s program, and the firm’s public silence on this likely reflected management’s concern about possible public criticism. The finance subsidiary fulfilled its subscriptions through the acquisition of AT&T shares on the open market. Along with helping to provide liquidity for the parent’s shares, management expected such support over time to maintain and then increase share value. A similar practice had been followed beginning in 1913 with the employee’s retirement plan, which was funded by AT&T debentures. Footnote 52 Along with Bell’s employee stock purchase plan (formed in May 1921), which also served as its market agent, BTS controlled a share portfolio that had the ability to support prices at critical junctures, such as when new shares were distributed through rights offerings or bond conversions. Footnote 53

A relatively unsuccessful rights offering completed in July 1921 was followed by the launch of BTS the following September. This occurred at the nadir of the 1920–1921 stock market decline that accompanied economic turmoil as the national economy rapidly shifted after World War I to a peacetime footing. About 7 percent of the rights went unexercised and the premium above par on average was less than $3 per share for the 898,000 shares distributed. Footnote 54 Beyond market conditions, the poor showing was attributed to the fact that many shareholders were unfamiliar with the complexities of exercising their rights, while the traditional Eastern markets for Bell stock were surfeited.

BTS’s launch also had a political dimension. The investment provided a link for developing support among the nation’s middle class for the heavily regulated firm and its various agendas. Share ownership helped to create a common bond for making more concentric the sociopolitical outlooks of the company and the public. This perception was reflected in the instructions given to members of the commercial department of the Illinois Bell Telephone Company concerning their role in the “redistribution” of parent company shares. Both financial capital requirements and the coalescence of public support were given equal weight:

The first is that the public will, as a result, become more keenly interested in our problems and will come to understand them better, in other words, it is the best possible public relations’ work. The second is that as our securities become more popular through a widespread distribution, the enormous amounts of capital required to develop the telephone business can be secured on a cheaper basis. Footnote 55

The rationale for the closer linking of business and community was expressed through ideas first defined within the firm by Malcolm Churchill Rorty, a vice president who had formed the Bell Systems statistical division under Vail and for a time was president of BTS. Rorty, an engineer, had a strong personal interest in economics and sociology. He was a founder of the National Bureau of Economic Research and a supporter of the work relating to business cycle analysis pursued by Professor Wesley C. Mitchell at Columbia University. His conservative perspective was reflected in his 1922 volume, Some Current Economic Problems, which considered how capitalism could effectively respond to Socialist criticisms about the equitable distribution of society’s economic surplus. Footnote 56

Rorty believed that it was important to promote “customer ownership” for natural monopolies, such as the fast-growing electrical utilities and electrical power companies, as a means to ensure “a natural and continuing relation of cooperation between the public and business.” Footnote 57 He felt this could only emerge when ownership interests were broadly distributed and not concentrated in few hands. He envisioned a type of relationship that went beyond regulation. At its heart was the commitment of the enterprise to offer only the soundest securities to the public, commensurate with their level of investment knowledge. Novice investors would be encouraged to buy preferred shares, leaving common shares to the more experienced investors. Investment safety would be further ensured through the steady provision of reliable information about the firm and its prospects. Footnote 58 The satisfaction of these requirements in Rorty’s view had the potential:

[To create] an effective agency toward the development of habits of thrift; it offers sound investments at good rates of return to many who have lacked or been ignorant of such opportunities; it assists in the adequate development of utilities to meet community needs; and in the end it must conduce to the building up of relations of mutual confidence and helpfulness between the utilities and their customers. Footnote 59

These purposes and visions would soon be implemented under the leadership of David F. Houston, BTS’s president, who had played a leading role in helping the administration of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to fund national defense efforts in World War I through the Liberty and Victory Loan programs. Footnote 60 Houston served in the Wilson administration as both Secretary of Treasury and Secretary of Agriculture as well as as an ex officio member of the Federal Reserve Board. Importantly, he was on hand for the government’s issue of four sets of Liberty Bonds in 1917 and 1918. Houston stated that the public’s participation in funding World War I had revealed “the fact that there were vast numbers of small investors, who had savings and were willing to invest them.” Footnote 61

Sharpening the Vision

Houston’s management of the financing subsidiary sought to turn the large, dispersed American middle class into Bell investors, especially outside of the Northeast where the firm already had a strong investor base. Houston had excellent knowledge of conditions in the South and West. A native North Carolinian, he served as president of Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (1902–1905; now Texas A&M), the University of Texas (1905–1908), and Washington University of St. Louis (1908–1913).

In addition to his considerable contribution to the financial management of the new subsidiary, Houston played a key role in refining and extending Rorty’s earlier ideas about customer ownership into the more elaborate conceptual structure of the shareholder, or industrial democracy. Houston’s beliefs on the benefits of industrial democracy stemmed in part from his perceptions about the changing nature and successful socialization of big business. Footnote 62 From 1870s to the 1890s, families or a small group of shareholders dominated the big businesses that emerged. Houston felt such big entities became unpopular because of the many mistakes and controversies associated with their growing power, which were eventually counterbalanced through the extension of laws and regulations.

Houston received support from academic allies in his efforts to develop public consciousness of the benefits of broader public share ownership. Significant in this regard was Harvard University Professor Thomas Nixon Carver, who had briefly served in the Department of Agriculture when Houston was the agency’s secretary. Footnote 63 Like Rorty, Carver eschewed political radicalism and argued strongly in his 1926 work, The Present Economic Revolution in the United States, for share-builder programs for employees and the general public to empower labor. Footnote 64

The political economic scene began to stabilize after 1900 with the advance of Progressive reforms. This coincided with a discernible growth of public ownership of shares and life insurance policies that fostered strong financial linkages between small investors and the giant enterprises that were dominating the national economy. In his numerous speeches before business and finance groups, Houston pointed out that by 1925 small investors had accumulated sizeable amounts of common and preferred shares and life insurance through mutual insurance companies. In this way, he argued, labor and capital had created a new mutually beneficial relationship. In Houston’s view, contemporaneous critics of capitalism were often “demagogues” who drew on outmoded beliefs about the nature of business, beliefs that were more appropriate for the 1870–1890 period. The critics failed to recognize the change in public attitudes and relationships with large businesses. Houston argued that the linking of labor and capital provided great assurance of the survival of capitalist institutions:

There is no assignable limit to the development of industrial democracy. The practice on the part of corporate businesses of inviting popular ownership is extending. Herein lies the solution of labor and capital. It is the real solution of the problem of partnership of labor and industry. And labor itself, as such, is embarking upon capitalistic enterprise. It recognizes that capital is the result of work and savings and that its destruction would cause a reversion to primitive practices. It will come more and more to perceive that the paramount need is to increase the world’s output. To expand the amount that can be distributed, and to raise the standard of living of everybody. In such fashion are the foundations of American democracy being strengthened and through the process of evolution by which the workers are becoming capitalists, American democracy is being rendered impregnable. Footnote 65

Houston ascribed American greatness to several factors, one of which was the freedom afforded the individual to experience personal growth and the opportunity to advance his or her material well-being. This potential was significantly extended by new linkages for translating the product of labor into the wealth-enhancing equity of public companies. The success of democracy also required the understanding of its unique definitions of the relationship between humankind and society, an understanding that was not automatic but had to be learned. Houston frequently illustrated this point through presentation of illiteracy statistics that purported to explain the failure of democracy in European countries during the 1920s. In America, however, educational levels were high, facilitating the understanding of the complex set of relationships that supported democracy. Knowledge and freedom combined to enable free men to pursue their self-interest. From the standpoint of material betterment, the freedom associated with democracy and the opportunity to participate through direct investment in the large businesses transforming the U.S. economy represented socioeconomic solutions to the Progressive’s dilemma. Houston viewed the laws and regulations of the democratic polity as successfully constraining the abuses of power prevalent from the 1870s to the 1890s, giving the average citizen the opportunity to benefit from industrial advancement through direct investment in the tamed lions of capitalistic endeavor.

The writings of both Rorty and Houston show Bell management contributed to an atmosphere where the ideals of democracy, capitalism, and freedom were intertwined. The firm sought to conflate the national telephone system—and AT&T—with that of American democracy, as seen in the 1921 advertisement (figure 2) in which a diverse body of Americans—laborers and housewives, businessmen and maids—were seen as collectively supporting American industry (with the telephone prominently displayed). Footnote 66

Figure 2 Ad in the New York Times.

Source: Advertising and Selling, 1921.

Management’s vision of industrial democracy further benefited Bell System by facilitating the distribution of ownership in regions of the country that had shown little previous investor interest, particularly in the largely populist South and West. Footnote 67 This meant relying on the insight and efforts of the local, regional Bell personnel. Quite possibly, management hoped that the spread of small-investor ownership in these regions would strengthen the firm’s political position in the local rate regulation debates over how best to allocate the costs of a vital public service. The creation of a national constituency, moreover, supported the firm’s contention that it was involved in knitting together people spread across a continent, a contention most obviously demonstrated by the existence of the firm’s long-distance operator—Long Lines Footnote 68 —but also actively expressed by the firm’s marketing efforts. As claimed in one advertisement, the trunk lines of the Bell System were instrumental in “Uniting a Nation” by connecting “cities, towns, and rural communities.” Footnote 69

Changes in stock ownership were part of an overall changing picture of property ownership that reflected the evolution of the U.S. economy from rural to urban and from individual ownership of productive assets to corporate control. Bell management was not alone in seeing the ramifications of these changes. Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means, contemporaneous observers of the American corporate landscape, worried about potential problems that could arise from the separation of ownership and control of corporate assets. They observed that fundamental questions relating to ownership and management of property influenced “the political determination as to the kind of civilization the American state in its democratic processes has decided it wants.” Footnote 70 The assets owned by the corporation were expected to benefit more than just the owners, and politics determined how much social cost should be borne by owners versus the public. Ensuring the existence of a shareholder group as a political constituency whose interests were aligned with those of the firm would be beneficial to any firm.

State-level entities exercised the most significant governmental power over the property rights of the telephone company. The broad purpose of state supervision was to protect the public interest by ensuring efficient and economical service. The economy standard pertained to reasonableness of cost, while efficiency related to the quality of transmission services. To achieve these goals, the regulatory bodies were endowed with broad authority to specify such matters as the costs recoverable through the rate base, the rules for financial accounting, the composition of corporate capital structure, and the types and level of employee compensation. Footnote 71 The reality of operating under a multitude of state regulatory jurisdictions meant nearly continuous litigation over the firm’s rates and rate structure. Building and maintaining a supportive national constituency could potentially minimize costly litigation. Public support, therefore, became an important sociopolitical issue to the firm.

Along with providing a source of necessary funds for capital expansion, creation of a public constituency for Bell could help to preserve the existing economic order if management was successful in aligning the interests of the firm with that of the broad shareholder–public constituency. With rising wages and the early retirement of Liberty Bonds used to finance American involvement in World War I, the timing of a program to increase corporate share ownership seemed propitious. Execution of this program, however, was problematic because the proper infrastructure did not exist to help turn savers into investors. BTS’s operations met this need.

Implementing the Vision

In pursuing the vision of industrial democracy, BTS implemented four basic policies. First, it helped to stabilize the price of AT&T stock through the steady purchase of shares as part of the effort to broaden ownership among both small investors and employees. Second, it enlisted employees, usually from its regional operating companies, to play an active role in the sale of securities. Third, it provided information to prospective investors about the firm’s business and finances to induce purchases by reducing risk perceptions. Fourth, BTS explained the intricacies of exercising periodic preemptive stock rights, a major source of equity financing, to shareholders who lacked sufficient knowledge to take advantage of these offers.

BTS was not the first financing company created by the Bell System; prior to the formation of BTS, AT&T had periodically incorporated subsidiary companies to assist in the sale of securities and in the acquisition of independent telephone companies. One such subsidiary, organized in 1906, was The Diamond State Co., which in 1909 acted as the agent of AT&T in acquiring shares of Western Union Telegraph Company and in transactions involving several operating subsidiaries, including New York Telephone & Telegraph Co. and Bell Telephone Co. of Buffalo. Another wholly owned finance subsidiary formed in 1903 was The Atlantic & Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. This company acted as the agent in acquiring minority shares held in associated companies and in acquiring independent companies and competitors. These initiatives were efforts on the part of Vail, as the new AT&T president, in restructuring operating companies and territories. These short-term entities had important and specific regional targets. BTS, in contrast, was a Bell finance subsidiary that operated both regionally and nationally, and its operations were usually tailored to the specific requirements of the regions in which it operated. For example, the first campaign undertaken by BTS in 1921 was for Southwestern Bell, a widespread territory that required intensive organizing, beginning in several Texas cities before spreading to Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. The campaign lasted three months and involved both Bell employees and local banks. In contrast, the second campaign, which was for Wisconsin Telephone, lasted only several weeks and relied primarily on sales by employee. Footnote 72

As an extension and complement to its education program, BTS developed its “direct sales plans” with participating Bell operating subsidiaries by soliciting and processing share orders from small investors. The operating subsidiaries were the regional Bell companies, which provided local telephone services. Initially, the brokerage firm Kidder, Peabody had been selected to perform these functions because of its wholesale and retail capacities and its long professional association with the telephone enterprise. Footnote 73 However, a major shortcoming of Kidder, Peabody was the fact that its retail business was largely centered in New England, where there was already a high concentration of Bell System owners. Unfortunately, there were no national commission houses at this time that could attract capital from all regions of the country. Footnote 74 Nevertheless, the hope was that Kidder, Peabody would prove successful in increasing the volume of AT&T share ownership among middle-class investors. However, Kidder, Peabody’s charges for facilitating the national distribution of small share parcels proved unacceptably high. Footnote 75 Moreover, regulatory barriers to expand the pool of owners also existed. New York State, where AT&T was incorporated, required that new equity issues be offered to existing owners first, meaning that the only way new owners could usually acquire shares was on the open market. Open market transactions required the services of a brokerage firm; however, as noted by Houston, small investors did not have access to these services because “some of them liv[e] in communities which are further away from brokers than Cleveland is from New York.” Footnote 76

While the average small saver might not have been familiar with investment firms, they were familiar with the Bell System and its employees. According to Bell lore, customers began to ask if they could purchase shares directly from the phone company, initiating the direct sales experiment. Footnote 77 When Bell employees made offerings of associated company preferred stock, their relative success as a sales and distribution force became apparent. As an example, the 1922 offering of almost 122,000 preferred shares of 7 percent Southwestern Bell was sold to 22,000 new subscribers—of which only 1,800 came through bank or brokerage channels. Footnote 78 Emphasis was placed on employees as a sales force Footnote 79 ; over the years, the differences in relative efforts were reflected by terming the sales campaigns as either light or intensive.

Under the BTS structure, AT&T began consolidating customer orders collected at local telephone offices and placing these orders to acquire shares on the open market. Customer orders were for cash, either paid in full or in installments. By concentrating purchases in this way, BTS could reduce the basic sales fee to less than 25 cents per share. Footnote 80 These charges were substantially lower than those that would have been incurred had small investors made odd-lot purchases through broker-dealers at the New York Stock Exchange. (Exchange investors had to pay an odd-lot dealer’s charge of 50 cents per share as well as a broker’s commission based on the value of the transaction.) Plan changes occurred periodically with an eye toward aiding the small investor: in 1931 the minimum monthly installment decreased to $10 (from $20); in 1932 the initial installment payment was decreased to $30 (from $50). Footnote 81 For installment purchases, the parent company advanced funds to BTS to acquire and hold stock until the subscription was fully paid. BTS paid 6 percent interest on outstanding balances, Footnote 82 a significant return on savings for the small investor. This also set the expectations for investors to receive a return of approximately 6 percent, a message communicated throughout the 1920s, during which time the firm often described its common stock in bond-like terms. AT&T had long offered a 9 percent dividend on $100 par value stock. Footnote 83 The cost of equity capital, however, was reduced if subsequent share issuances (deriving from rights offerings, debenture conversions, or installment sales) were made at high premiums over par. Thus, the average share market value of $136.9735 for 1.5 million shares issued in the 1926 rights offering had an effective dividend rate of about 6.5 percent.

With a par value of $100 and a higher market value, AT&T shares were still expensive for the average American. The introduction of installment purchases allowed potential investors with limited capital to become AT&T shareholders. Footnote 84 BTS’s establishment of a separate financing division was not unique. Installment sales were by now familiar to Americans; General Motors had formed General Motors Acceptance Corporation in the 1920s to promote selling automobiles on the installment plan, while less progressive Ford lost market share by offering consumers only a lay-away plan that required a contribution of $5 per week until the car was completely paid for and before title transfer. Footnote 85 AT&T brought this installment model of consumerism into its strategy of share sales to widen its shareholder base. Although other utility firms sometimes allowed customers to purchase shares when paying their bills, AT&T had a more aggressive use of installment stock purchases. Footnote 86

Another function of BTS was to help stabilize AT&T share prices by acquiring large blocks of parent company shares on the open market in anticipation of subscription fulfillment. The price support efforts were generally successful until the shock of the great crash of 1929. From 1923 to 1926, for example, BTS’s purchases on behalf of small investors and employees represented between 21 percent and 38 percent of the average daily AT&T share volume (which numbered in the several thousands) on the New York Stock Exchange and Boston Stock Exchange. Footnote 87 Another index of market influence was that BTS was “ranked from sixth to second in number of shares voted by single stockholders between 1926 and 1932.” Footnote 88

Market price support operations also facilitated the rights offerings that enabled existing shareholders to maintain their proportional interest in the firm’s equity. From 1921 to 1930, through six such offerings, shareholders could subscribe for a new share at par value of $100, irrespective of market prices, for each five or six shares already owned. Footnote 89 Shareholders benefited from the ability to acquire additional equity at a discount if the market price stayed above par. Approximately 35 percent to 40 percent of the shareowners during this era, on average, held only three shares, resulting in fractional ownership of rights. Because of this, about a half of the total rights granted during this period were sold into the market to other investors. Footnote 90 In this case, the proceeds from the rights sale functioned in effect as a dividend to the seller. The higher the market price, the more attractive was this form of financing. Between 1921 and 1935, AT&T shares varied in price, from a low of $70.23 (1933) to a high of $310.25 (1929). Footnote 91 During that same period, Bell issued 8.5 million new shares, which represented about 47 percent of the 18.6 million outstanding in 1935. Footnote 92

Market support activities of BTS and the employee stock purchase program helped to lower the firm’s cost of capital and increased total shares outstanding through debt conversions to equity, through the sale of unsubscribed rights, and through installment sales of shares to employees. From 1923 through 1931, Bell issued more than four million shares for these purposes, at a premium over par, aggregating $217 million. The premium reduced the effective dividend rate from 9 percent based on the par value to about 5.8 percent. Footnote 93 Overall, this resulted in a lower cost of equity capital; in 1935, for example, the cost of equity capital stock amounted to 7.87 percent as compared to the 9 percent dividend rate. Footnote 94

As part of its efforts to eliminate informational asymmetries that would deter middle-class investors, BTS lowered information costs among AT&T shareowners who had a poor understanding of the firm’s periodic rights offerings. By exercising rights, existing stockholders could ensure that the upcoming stock offering did not dilute their ownership. Many small investors, however, were confused by the idea of stock rights, and so let them expire. The BTS staff of about ten permanent employees reduced investor uncertainty through explanatory media: advertisements, pamphlets, and letters. Articles in the Bell Quarterly regularly discussed the extensive, time-consuming efforts made to contact rights-holders individually and then walk them through the process of rights’ exercise. Footnote 95 The fact that AT&T was prepared to accept these costs shows the value the firm management placed on this activity. The actual processing of rights was left to AT&T’s New York’s treasury department. Although normally numbering about two hundred employees, rights offering were timed each year so that four hundred summer employees, usually college students on vacation, could complete this work. The new issues were announced during the spring. Deadlines for subscribing to new issues generally were in early June. Most of the administrative work associated with the registration of new ownership interest was completed by August. Footnote 96

BTS reduced transaction costs by accumulating large parcels of rights to facilitate the economical buying of shares in the market. In accumulating orders, BTS achieved economies of scale that reduced average transaction costs and increased the scope of the potential subscriber base. Most individual investor rights during the 1920s were transacted in small lots of one to five shares, quantities normally not economical for brokers to handle. Additionally, the exercise of these rights was allowed to proceed through cash installments paid over eight months, increasing the ability of those of limited means to accumulate enough capital for share purchase. Footnote 97 Thus, BTS’s operations benefitted the Bell System by securing new financing while simultaneously providing economic benefits to its small shareholders.

AT&T’s emphasis on ensuring that shareholders participate in preemptive rights’ offerings was unusual because its purpose was both to supply capital to the firm and to promote the stock’s value for existing holders. In their contemporaneous study of U.S. stock ownership, Berle and Means noted that stock rights offerings often served the purpose of diluting stock ownership and hastening the separation of ownership and control of corporations. However, while criticizing the role of rights ownership in the dilution of existing stockholder control, these authors repeatedly cited AT&T as an exception to the general trend. They noted that contrary to the experience of most corporations, by issuing rights AT&T “enhances the value of the outstanding stock. It is in fact an automatic device preventing dilution of assets.” Footnote 98 As 1920s economist Harvard University Professor William Z. Ripley wrote, “the right of shareholders in a corporation to participate to their advantage in all subsequent issues of shares … is the very essence of corporate democracy.” Ripley generally saw firms’ efforts to sell stock to customers as attempted robbery, unlike “great corporations like American Telephone, which treats the matter (the existence of customer investors) from the high standpoint of a trustee.” Footnote 99

BTS worked out procedures for coordinating the activities of the regional operating subsidiaries in planning the collection of exercised rights, and it was successful in increasing the percentage of rights exercised. Footnote 100 The publicity efforts by a staid dividend-paying utility proved effective in attracting capital from risk-averse investors seeking other conservative investments to replace the massive retirement of Liberty Bonds. Perhaps as important, however, is that BTS increased the liquidity of these rights. At the first offering in 1921, five shares were offered for every share held, and purchase of the shares could take place in installments payable over four months. Footnote 101 In 1924 fractional share warrants were offered for the first time; though only full shares were issued, rights became tradable so that they could be bundled by secondary purchasers and exchanged for new shares. Footnote 102 In 1926 the number of rights assigned to each share increased to six. Footnote 103

BTS created a significant number of middle-class shareholders through its installment sales program; through its rights offerings, it also raised a substantial amount of capital for the Bell System. BTS also proved profitable for AT&T. Capitalized initially at $1 million, management believed that the new financing subsidiary would operate at break-even. Footnote 104 BTS received dividends and earned profits trading AT&T securities; from 1921 through 1935, BTS received dividends of $2.9 million on the common stock it held to support its stock subscriptions. It earned another $2.5 million from trading AT&T stock and $0.5 million in rights. Footnote 105 Interest and dividend income were also earned from the investment of surplus funds. Footnote 106

BTS’s expenses were negligible. Enlisting operating company personnel as a sales force facilitated the integration of the retail share distribution. This kept direct transactions costs low by eliminating the middleman between the firm and the customer–shareholder. Employees were routinely paid $1 for each new customer order, Footnote 107 substantially less than the earlier 1 percent commission paid to Kidder, Peabody. Footnote 108

The employee sales force also complemented the Bell System’s public relations activities. In 1912 AT&T formed a bureau in its statistics division, which provided information on “the trend of public opinion and the drift of legislation.” Footnote 109 With increasing frequency after World War I, Bell management pursued a public relations campaign that portrayed the firm as one dedicated to public service and that promoted “democratic capitalism.” Footnote 110 The involvement of local office staff in the sales effort served to enhance a spirit of pride within employees while creating a “folksy” image with the public.

Attempting to capitalize on a spirit of national pride engendered by the recent war, the advertising was also used to align the interests of the company with those of American society as a whole: what was good for Bell was good for America. Potential customers were reminded in a 1924 offering circular that “the investor in the securities of this Company purchases an interest in the telephone business of the entire country”; a 1926 circular went even further, stating that BTS served “the common good” Footnote 111 (figure 3).

Figure 3 Bell Telephone Securities Co. advertising circular.

Source: 1926 AT&T advertising circular.

The firm trumpeted the growth of its ownership base in its annual reports (figure 4) and company advertising, although it was selective in how the material was presented. Footnote 112 For example, at a 1926 Bell conference, attendee Yale Professor Irving Eisher tried to pin management down on how many shares were owned by the “typical owner,” but he was evasively answered by BTS President Houston, who stated: “The stock of the System is controlled by those who own one hundred shares or less.” Footnote 113 Unfortunately, moments later, Bell’s treasurer added that only eighteen thousand shareholders out of a total of four hundred thousand were needed to achieve a majority, indicating that some of these shareholders held a disproportionately large number of shares. This reality was echoed by Nestor Danielian, another critic, who noted in 1939 that while emphasizing no shareholder owned even 1 percent of its stock, AT&T did not mention that nearly 50 percent of the firm was held by only 5 percent of the owners. Footnote 114

Figure 4 Bell stockholders, 1900–1927.

Source: AT&T, Annual Report of the Directors of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, 1927.

Meanwhile, Bell employees at all levels were encouraged to become AT&T stockholders themselves. The employee stock-ownership plan was part of a larger effort to encourage employees to become thrifty, miniature capitalists. In addition to the stock-ownership plan, the company sponsored savings plans and life insurance with automatic pay withdrawals. Budget books were distributed free to all employees, and firm magazines contained articles on topics such as investing and insurance. As a national firm, increasing employee ownership helped create a loyal employee base and a substantial, geographically dispersed, middle-class constituency for the firm. These owners helped to foster the image of the Bell System as a group of ordinary working-class people—linesmen, operators, and so on—working to better their fellow citizens, and not just as a faceless, monolithic corporation. Due to their large numbers—excluding Western Electric, Bell employees numbered just under 300,000 in 1925 and nearly 325,000 in 1930 Footnote 115 —the firm’s employees constituted a sizeable public relations presence as well as a potential shareholder base.

Promoting broader geographic ownership among both customers and employees helped to create a community of investors that identified strongly with the policies of the heavily regulated utility. As stated in company promotional material, the firm wished to redefine its relationship with the public from merely “customers” to “partners.” Footnote 116 To this end, the direct sales program was eventually offered in forty-one states, Footnote 117 although it was most active in the Midwest and Southwest.

BTS used pamphlets, newspapers, magazine advertisements, letters, and direct representative consultation to distribute investment information. The intensity of such efforts varied among regions. BTS additionally sought to build up broader communities of interest for the regional operating companies by reducing information and transaction costs in the sale of subsidiary preferred stock issues, a significant funding source for the regional Bell operating companies. As in the case of the parent company’s common equity sales, BTS worked with the regional operating companies to advertise new stock issues and to develop organizational mechanisms to accept subscriptions and to distribute shares. Footnote 118

Concurrently, BTS played an active role in the liquidation of minority interests in Bell subsidiary common stock through exchanges with the equity of the parent company. Many of the subsidiary operating companies had originally been operated as franchises during the Bell System’s formative years as a means of conserving financial capital. As the firm prospered, it gradually repurchased shares from the original franchisees, but substantial balances still remained outstanding in a few cases as late as the 1920s. During that decade, it traded AT&T stock for shares in New England Telephone (acquired 8,906 common shares), Pacific Telephone and Telegraph (acquired 31,670 common shares), and Western Electric (acquired 21,620 common shares). Footnote 119

Impact of BTS’s Operation

Bell management launched BTS with the goals of raising capital for expansion; broadening ownership (particularly outside of the Northeast) of AT&T stock; and creating a positive, popular perception of the firm. Operations that supported the market price of AT&T stock had a favorable impact on raising equity capital through rights offerings and bond conversions, the major sources of new equity capital for the firm. Its stock price steadily advanced from a low of $92.13 in 1920 to a high of $310.25 in 1929, an increase of 331 percent. Between 1921 and 1930, there were six rights offerings, which distributed an additional 9.6 million shares. With the exception of the $2.8125 per share premium realized in the disappointing 1921 issue (which occurred three months before the formation of BTS), each flotation had average premiums that ranged from $18.75 (1922) to $123 (1930). By the end of 1930, the combination of rights and conversion issuances of 13.6 million shares represented about 61 percent of the 18.7 million shares outstanding. The exercise of convertible bond rights added an additional 4.2 million shares. Footnote 120

BTS’s direct and installment stock sales broadened the shareholder base. Consistent with the firm’s initial plan for the new subsidiary, about 85 percent of its activity pertained to small stockholders. Footnote 121 The number of shareowners increased from 40,000 in 1910; to 139,000 in 1920; and to 650,000 in 1935. Footnote 122 In addition, BTS redistributed another 600,000 shares through the employee stock option plan from 1921 through 1933. Footnote 123

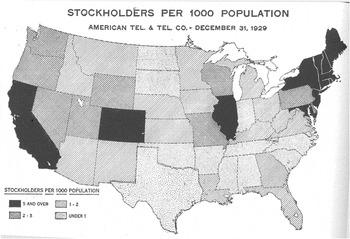

Demographic and geographic diversity of ownership was also largely achieved. The impact of the small investor was reflected in the decreased size of the average ownership position, dropping from seventy-six shares in 1900 to twenty-five in 1925. Footnote 124 No individual owned more than one-fifth of 1 percent of the firm’s equity, and more than 50 percent of the stockholders held ten or fewer shares. Footnote 125 Recall, however, that this overlooks the fact that only eighteen thousand shareholders, out of a total of four hundred thousand, owned a sufficient number of shares to constitute a majority, and this ownership segment had holdings far in excess of one hundred shares. Footnote 126 BTS also succeeded in broadening the distribution of its stock beyond the Northeast. There were stockholders in every state of the Union and eighty foreign countries. Twelve states had more than ten thousand stockholders each; twenty-two states had more than five thousand stockholders; no state had less than five hundred stockholders. Management’s success in geographically expanding the Bell System’s ownership base is clearly seen in figures 5 and 6. Figure 5 shows the map of the number of shareholders per one thousand of population in 1929; although large concentrations of ownership were still found in the Northeast, two western states (California and Colorado) had ownership rates at the same level (five or more shareholders per one thousand residents). Shareholders were now to be found in every state.

Figure 5 Bell stockholders by state, 1929.

Source: Bell Telephone Securities, Annual Report of the Bell Telephone Securities Company, 1929.

Figure 6 Percentage increase in Bell stockholders by state, 1921–1929.

Source: Bell Telephone Securities, Annual Report of the Bell Telephone Securities Company, 1929.

The second map (figure 6) shows the percentage gain in Bell stock ownership from the time BTS began its operations in the state until the end of 1929 and highlights its impact in expanding geographic dispersion. States in the south (Texas, Louisiana) and west (California, Idaho, Minnesota, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming) experienced increases in stockholders of between 700 percent and 1,000 percent.

Beyond geographic diversity, the Bell System succeeded in creating a shareholder class that crossed economic, cultural, and social boundaries (figure 7). A study of purchasers of Bell System stock in 1925 found that shareholders came from all fields; the five largest occupations identified from the more than two hundred thousand individual purchasers were 3 percent each executives and salesmen, 11 percent clerks, 16 percent laborers, and 17 percent housewives. Footnote 127 Women in general constituted a significant proportion of stockholders; in 1929, for example, women stockholders were said to outnumber men by eighty-four thousand. Footnote 128

Figure 7 AT&T subscribing shareholders by occupation, 1925.

Source: David Franklin Houston Papers, Item 311, Houghton Library, Call number MS Am 1510, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

BTS’s activity slowed as the Depression progressed. Footnote 129 The decade’s apex in system building was reached in 1930, when total system plant slightly exceeded $3 billion before it entered a period of gradual contraction. Firm revenues exceeded $1 billion in 1930, but they steadily fell back to about $850 million in 1933. Footnote 130

The Vision’s Legacy

Like many other firms, BTS did not survive the Great Depression, though not because of business failure. Rather, the circumstances—economic and political—that contributed to the success of BTS disappeared, and new costs in the form of increased regulatory scrutiny and burdens appeared. Furthermore, BTS had achieved its strategic purposes. It had facilitated the raising of large amounts of financial capital through rights offerings and debt conversion. It had also built a constituency of small, geographically dispersed stockholders who absorbed about 10 percent of the firm’s total equity. If the firm wished to continue to expand this constituency, there now existed retail firms to service such investors. However, the need no longer existed.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, stock subscriptions evaporated, as reflected in a lack of share growth subsequent to 1931. A steady increase in the number of shares outstanding during the 1920s moderated significantly in 1931, and then flattened out after 1935 (figure 8).

Figure 8 AT&T, number of shares outstanding, 1921–1935.

Source: FCC, Investigation of the Telephone Industry in the United States, Table 83, 508.

Along with the demand for stock drying up, the Depression eliminated trading gains for BTS. The Bell System became subject to ever-increasing, intense scrutiny from federal regulators. AT&T’s relationship with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) became more complex as, via BTS, the firm maintained its status as either a broker or dealer in several states. The decision to dissolve BTS came in 1936, partially in response to the forthcoming Revenue Act of 1936, with its proposed 15 percent tax imposed on dividends received by the parent enterprise from controlled entities such as BTS. Footnote 131 The likelihood of a future revival of BTS was effectively cut off by a highly critical report by the staff of the FCC, which in 1934 had become the most recent federal regulatory agency for the industry. The federal regulators were critical of the BTS arrangement, believing that it was a challengeable subterfuge that allowed the parent to deal in its own shares. Because BTS had achieved its purposes, Bell management did not feel the need to contest the FCC’s contention, and so the BTS was dismantled.

Conclusion