Introduction

Antarctic researchers make considerable efforts to generate new knowledge of the continent and its marine environment, often under challenging conditions (Jenkins & Palmer Reference Jenkins and Palmer2003). However, in the context of science-based decision-making, the impact of their work can be limited unless the findings are communicated to those who are in a position to act on the information (Weible et al. Reference Weible, Heikkila, DeLeon and Sabatier2012, Bednarek et al. Reference Bednarek, Wyborn, Cvitanovic, Meyer, Colvin and Addison2018). But how does an Antarctic researcher engage in communication at the science-policy interface when the workings of the Antarctic policy world may appear convoluted and the mechanisms of communication opaque? In this paper we provide researchers with an overview of science-policy communication pathways in an Antarctic context, as well as the knowledge and tools to help maximize the policy impact of their work. We provide academic researchers and other interested individuals with information on: the main international agreements relevant to Antarctica (primarily the Antarctic Treaty System; ATS), and in particular those relevant to environmental protection and conservation; how governance and management of Antarctica is undertaken, including details of the main stakeholders; how participants may engage in the work of ATS organizations and meetings; the role of science in Antarctica; topics of interest to the international bodies of the ATS where research might be undertaken; mechanisms for further engagement by researchers with Antarctic policymaking; and challenges at the science-policy interface. Definitions of key terms are provided in Box 1, and a full list of organizational acronyms is provided in Table I alongside relevant sources of online information.

Box 1. Definition of terms.

Table I. Common abbreviations used in the context of Antarctic governance and management with associated websites as relevant.

Main international agreements relevant to Antarctica

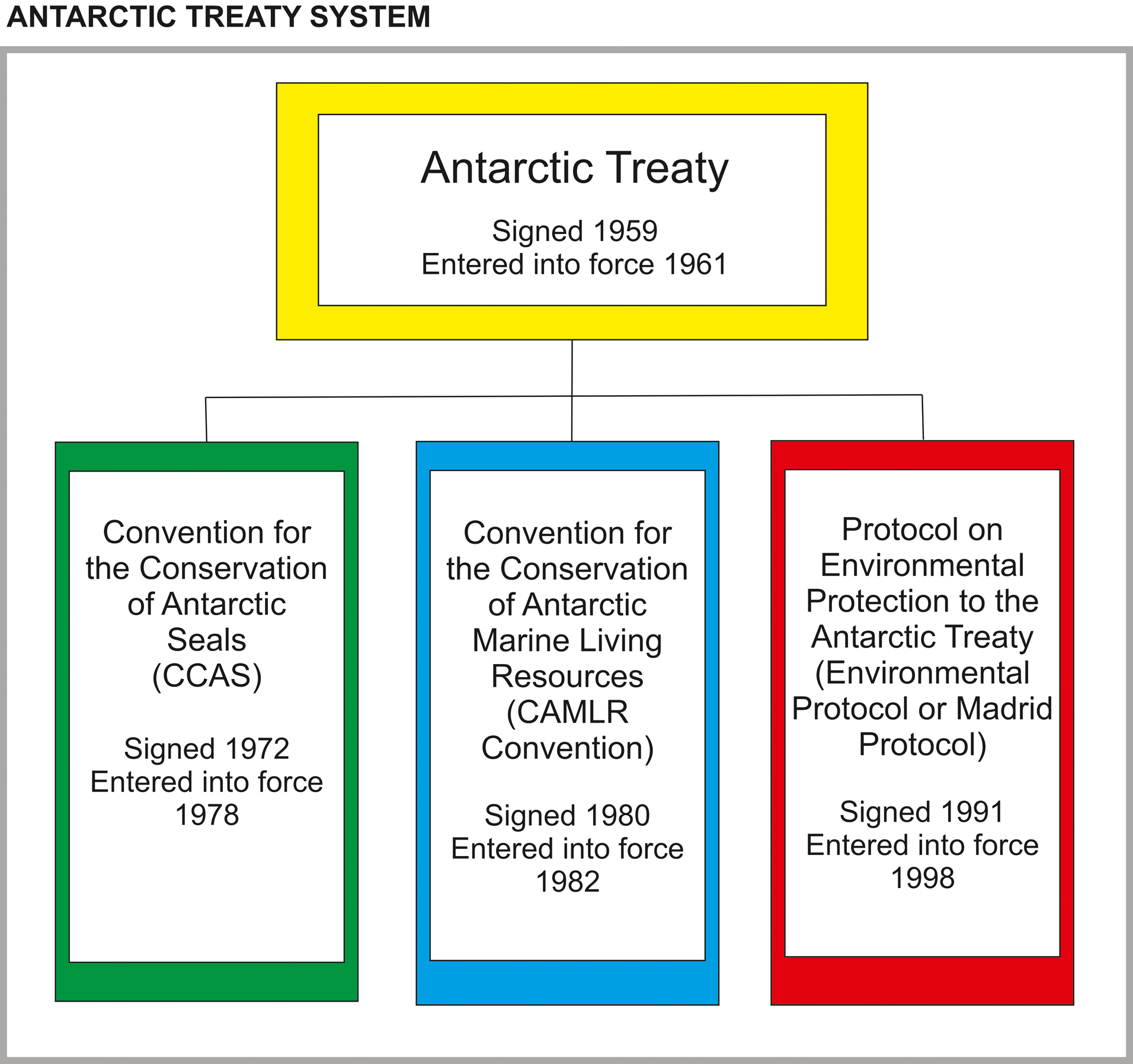

The ATS is composed of four international agreements: the Antarctic Treaty itself, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention) and the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS; see Fig. 1; Scully et al. Reference Scully, Berkman, Lang, Walton and Young2011). The ATS is further augmented by agreements adopted at the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs) and Conservation Measures adopted at meetings of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). Other legal instruments that sit outside the ATS, such as the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP), have direct relevance to Antarctic conservation and are briefly described.

Figure 1. International agreements comprising the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). The ATS is further augmented by Recommendations adopted by the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings.

Antarctic Treaty

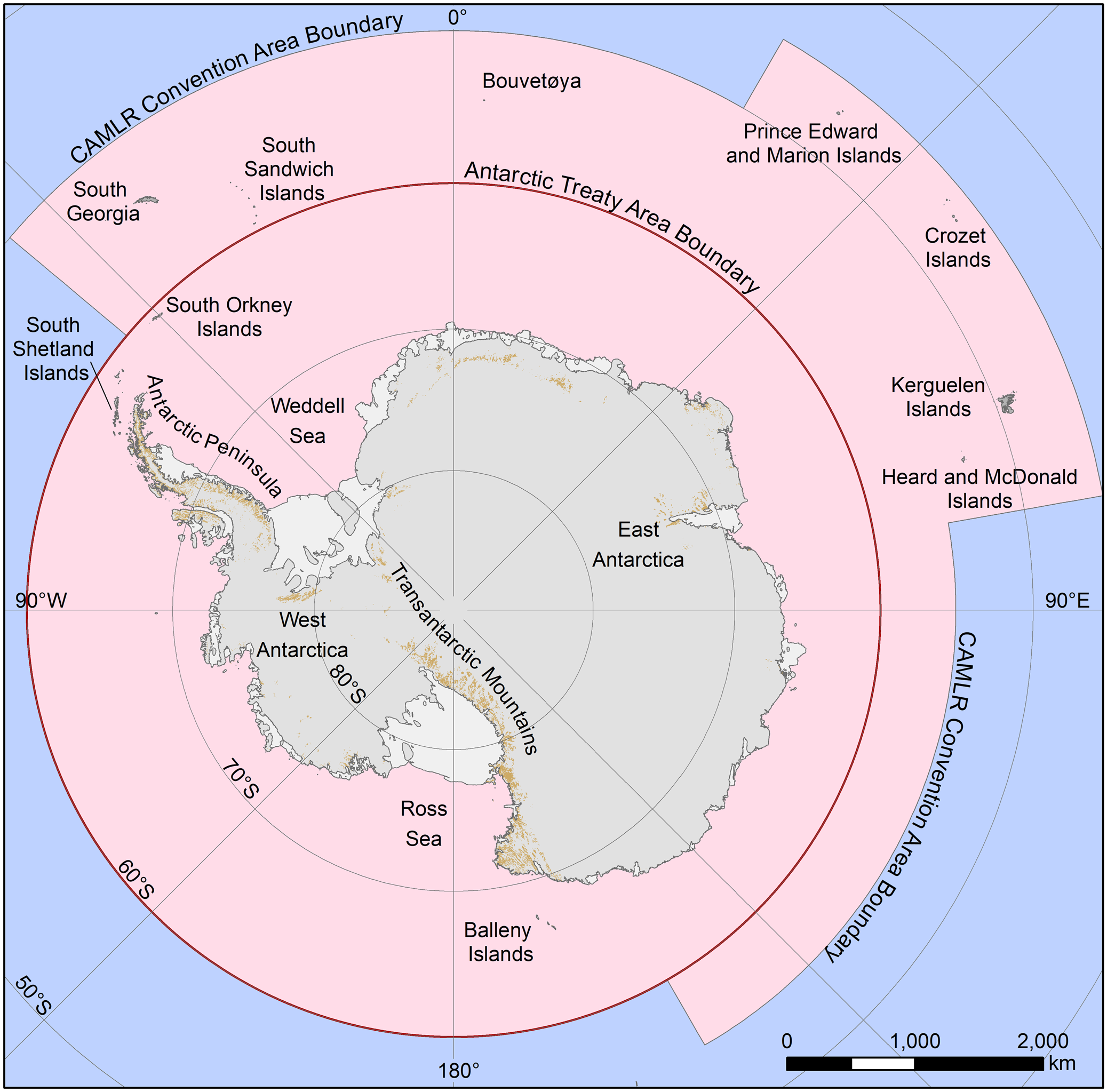

The Antarctic Treaty was signed on 1 December 1959 by the 12 countries whose scientists were active in the Antarctic region during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–1958 (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, the Soviet Union (now the Russian Federation), South Africa, the UK and the USA). The Treaty subsequently entered into force on 23 June 1961, and the first ATCM commenced 17 days later. The Treaty applies to the Antarctic Treaty area, which is the area south of latitude 60°S (Fig. 2). Provisions of the Treaty include that: 1) Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only, 2) freedom of scientific investigation in Antarctica shall continue, 3) scientific observations and results from Antarctica shall be made freely available, 4) military activity is prohibited, except in support of science, 5) nuclear explosions and the disposal of nuclear waste in the Antarctic are prohibited and 6) territorial claims shall be put into abeyance (i.e. those of the claimant states: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK). Parties have recently reaffirmed their commitment to the Treaty through, for example, the Paris Declaration 2021 (ATCM XLIII; see https://documents.ats.aq/ATCM43/ad/ATCM43_ad004_e.docx). At present, 56 nations have signed the Treaty.

Figure 2. Map of the Antarctic region, showing the Antarctic Treaty and Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources areas.

Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty

The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (also known as the Environmental Protocol or Madrid Protocol) was signed in 1991 and entered into force in 1998. The Protocol designates Antarctica as ‘a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’, prohibits all activities relating to Antarctic mineral resources, except those undertaken for reasons of scientific research, and has six annexes concerning 1) environmental impact assessment (EIA), 2) conservation of fauna and flora, 3) waste disposal and management, 4) prevention of marine pollution, 5) area protection and management and 6) liability arising from environmental emergencies (yet to enter into force). The Protocol established the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) as an expert advisory body to provide advice and formulate recommendations to the ATCM in connection with the implementation of the Protocol (McIvor Reference McIvor2020). At present, 42 nations have acceded to the Protocol and, by doing so, are entitled to send representatives to attend meetings of the CEP.

Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

The CAMLR Convention was adopted in 1980 and entered into force in 1982 primarily as a multilateral response to concerns that unregulated increases in krill catches in the Southern Ocean could be detrimental for Antarctic marine ecosystems, particularly for seabirds, seals, whales and fish that depend on krill for food. The Convention applies to all Antarctic populations of finfish, molluscs, crustacea and sea birds found south of the Antarctic Convergence (the Convention Area; see Fig. 2). The Convention Area extends north to a line loosely based upon the southern boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. As a result, the area includes the waters north of the Antarctic continent as far as latitude 60°S and in some case further north, which includes ocean areas around several sub-Antarctic islands (see Fig. 2). Unlike other instruments of the ATS, the Convention applies to waters that are subject to the governance of sovereign nations. In waters under national jurisdiction, the country in question can choose whether or not to abide by CCAMLR decisions. The CAMLR Convention does not consider the conservation or harvesting of whales and seals in the Antarctic region, which are considered under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and CCAS, respectively, although neither sealing nor whaling occurs currently. However, CCAMLR does consider the conservation of these species through, for example, specific regulations and Conservation Measures to 1) mitigate the incidental mortality of seals and whales by fishing vessels and 2) maintain populations of all krill-dependent predators.

The CAMLR Convention established CCAMLR as the primary decision-making body responsible for enacting the Convention. The Scientific Committee of CCAMLR (SC-CAMLR) was formed as a consultative subsidiary body to provide the best available science that the Commission can draw upon during its decision-making. CCAMLR Contracting Parties are states or regional economic integration organizations, such as the European Union, that have committed to the Convention through ratification or accession. Thirty-seven Contracting Parties have acceded to the Convention.

Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals

CCAS was agreed in 1972 to regulate a possible resumption of sealing activities within the Treaty area, including through the establishment of 1) annual catch limits for each seal species, 2) six sealing zones, 3) a sealing season and 4) three seal reserves. However, when CCAS finally entered into force in 1978, no sealing industry had developed in Antarctica. Currently, 16 nations have acceded to the Convention. CCAS has now been largely superseded by Annex II Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which in effect prohibits the commercial harvesting of seals (Convey & Hughes Reference Convey and Hughes2022).

International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling

The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, which regulates global whaling activities, was agreed in 1946, predating the establishment of the ATS (Gales Reference Gales2022). As a result, this Convention sits outside the ATS, but it does have jurisdiction concerning whaling within the Southern Ocean, including the waters of the Antarctic Treaty area. Currently, 88 countries adhere to the Convention and are Members of the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels

ACAP is not a component of the ATS and was concluded under the auspices of the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species. It was opened for signature in 2001 and entered into force in 2004 (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Baker, Double, Gales, Papworth, Tasker and Waugh2006). ACAP's aim is to conserve albatrosses and petrels by coordinating international activities to mitigate threats to their populations. A key focus of ACAP is to review and assess the status and population trends of all 31 ACAP-listed species (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Gales, Baker, Double, Favero and Quintana2016). Thirteen countries (Parties) have now joined the Agreement.

Other international agreements outside the Antarctic Treaty System

Several other international agreements that apply globally also include Antarctica within their jurisdiction. Examples include the many conventions that the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is responsible for keeping up to date, and, in particular, the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code; Deggim Reference Deggim, Hildebrand, Brigham and Johansson2018). The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ostensibly also applies to the Southern Ocean, although interactions between UNCLOS and the ATS have rarely occurred and the relationship remains largely untested (Joyner Reference Joyner2010, Malone Reference Malone2018).

How governance and management of Antarctica is undertaken: meetings and stakeholders

In this section, we describe the main actors engaging in Antarctic governance or the provision of expert advice or scientific information and the meetings at which many of these interactions occur. Information was largely derived from organizational websites (see Table I) and/or communication with organizational representatives.

Meetings: Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting

Since its first meeting in 1961, the ATCM has been the forum for governance of the Antarctic Treaty area. Each year the ATCM is held ‘for the purpose of exchanging information, consulting together on matters of common interest pertaining to Antarctica, and formulating and considering and recommending to their Governments measures in furtherance of the principles and objectives of the Treaty’ (Article IX). Parties may participate in ATCM decision-making (termed a ‘Consultative Party’) if they are one of the 12 original signatory nations to the Treaty or if they have demonstrated, to the satisfaction of the ATCM, their interest in Antarctica via undertaking ‘substantial scientific research activity’ there. In addition to the original signatories, 17 countries have met this requirement, making a total (at present) of 29 Consultative Parties.

At the ATCM, proposals and information exchange occur through the provision of papers to the Meeting, of which there are three types: Working Papers, Information Papers and Background Papers. Working Papers can only be submitted by Consultative Parties or Observers (i.e. CCAMLR, Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) and Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR)), are translated into the four official languages of the Meeting (English, French, Russian and Spanish) and should contain recommendations that require the consideration of the ATCM and are presented orally at the Meeting. Information Papers can be submitted by all ATCM participants, are made available to the Meeting only in the language in which they were submitted, do not contain recommendations and their oral presentation at the Meeting is not guaranteed. Background Papers are similar to Information Papers, with the exception that they are not presented orally at the Meeting. Papers submitted to the ATCM (and CEP) are available from the Meeting Document Archive of the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty (https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e). The papers mentioned above are quite different from academic papers. Papers submitted to the ATCM may express the views or perspectives of the authoring Parties or organizations. Where information is provided, it may be based on peer-reviewed publications; however, this is not always the case, particularly when papers concern issues such as updates on national logistical arrangements or the operation of the ATCM, about which scientific publications are unlikely to be available.

Proposals, which are generally brought to the attention of the ATCM through Working Papers, must be approved through consensus by the Representatives of the 29 Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treaty (i.e. the proposal will not be approved if one or more Parties object). The term ‘consensus’ can be taken to mean a mutually acceptable decision that integrates the interests of all concerned parties (Brockett et al. Reference Brockett, Clarke, Lindsay, Scherzer and Wilson2005) and in an ATS context is generally considered to be an ‘absence of any objection’ to a proposal or recommendation. Consensus is not the same as unanimous agreement, as the decision may not satisfy each Parties' concerns or interests equally or receive equal levels of support. The 27 non-Consultative Parties may attend the ATCM but do not participate in decision-making. Observers to the ATCM, which are organizations invited to attend and provide expertise and other perspectives at meetings, include the representatives of CCAMLR, COMNAP and SCAR. Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (ATCPs) and CCAMLR, COMNAP and SCAR may submit Working Papers to the Meeting that contain recommendations for consideration by the ATCM. In contrast, non-Consultative Parties and scientific, environmental and technical organizations designated as Invited Experts (listed at the end of this section) are not permitted to provide Working Papers but may provide Information Papers to the Meeting, where they may be introduced (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Venn diagram showing the membership of the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM), the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP), including selected organizations participating as Invited Experts or Observers. Representatives of CCAMLR attend the ATCM and CEP meetings. Representatives of CEP attend the ATCM and CCAMLR meetings. Countries are labelled according to their three-letter country codes (see https://www.iban.com/country-codes). EU stands for the European Union, which has membership within CCAMLR. ATCM: red circle; CCAMLR: blue circle; CEP: green circle. Black bold: Consultative Party to the ATCM, CCAMLR Member, CEP Member. Black, bold and italics: Consultative Party to the ATCM, Acceding State to CAMLR Convention, CEP Member. Black italics: Non-Consultative Party to the ATCM, Acceding State to CAMLR Convention, CEP Member. Red bold: Non-Consultative Party to the ATCM, non-signatory to CAMLR Convention, not a Member of CEP. Blue bold: Non-signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, Full Member of CAMLR Convention, not a Member of CEP. Blue, bold and underlined: Non-signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, Acceding State to CAMLR Convention, not a Member of CEP. Green bold: Consultative Party to the ATCM, CEP Member, non-signatory to CAMLR Convention. Green: Non-Consultative Party to the ATCM, CEP Member, non-signatory to CAMLR Convention. Selected Invited Expert and Observer Organizations are shown in purple. ACAP = Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels; ARK = Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies; ASOC = Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition; COLTO = Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators; COMNAP = Council of Mangers of National Antarctic Programs; IAATO = International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators; IWC = International Whaling Commission; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research; WMO = World Meteorological Organization.

Since the early 1990s, the ATCM has been held annually (usually between late April and early July), with the meeting hosted by one of the Consultative Parties (with the host normally moving in alphabetical order according to the English name for the nation). Simultaneous interpretation (speaking) and translation (of written materials) services are provided for the four official languages of the Treaty. The Meeting may divide its agenda between Working Groups, with recent Working Groups having been concerned with issues relating to ‘Science, Operations and Tourism’ and ‘Legal and Institutional Matters’. The activities of the ATCM are coordinated through its Multi-year Strategic Work Plan (e.g. see https://documents.ats.aq/ATCM44/att/ATCM44_att001_e.docx). As needed, the ATCM can convene an Antarctic Treaty Meeting of Experts (ATME) to consider a specific subject, with previous issues including climate change, tourism and shipping. The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat assists the ATCM and the CEP in performing their functions and is based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The ATCM considers many issues of relevance to the governance of the Antarctic Treaty area, including liability arising from environmental emergencies, biological prospecting, exchange of information, education, safety and operations, inspections under the Antarctic Treaty and Protocol, science, future science challenges, scientific cooperation and facilitation, the implications of climate change for management of the Antarctic Treaty area, tourism and non-governmental activities in the Antarctic Treaty area and competent authorities issues. The ATCM also considers the report of the CEP, which advises and provides recommendations on the implementation of the Protocol (see below). The annual ATCM meeting reports are available on the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat website (https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Info/FinalReports?lang=e), along with the documents submitted to the meetings by the Antarctic Treaty Parties, Observers and Invited Experts (see https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e).

The ATCM receives science knowledge from several sources. A Party may communicate research information obtained by their nation's researchers via Working Papers, Information Papers or Background Papers to the Meeting. Alternatively, the ATCM may request or receive relevant science information in papers submitted by scientific research bodies, including the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) or SCAR. Each year, the ATCM also invites SCAR to provide a science lecture at the meeting.

Meetings: Committee for Environmental Protection

The CEP was established by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty and first met in 1998, the same year in which the Protocol entered into force. The Committee's functions are ‘to provide advice and formulate recommendations to the Parties in connection with the implementation of this Protocol, including the operation of its Annexes, for consideration at Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings’ (Article 12). The CEP membership comprises all Parties that are signatories to the Protocol. Currently, this comprises all 29 Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treaty and 13 non-Consultative Parties. Observers to the Meeting include CCAMLR, COMNAP and SCAR. Other relevant scientific, environmental and technical organizations may attend meetings of the CEP subject to the approval of the ATCM. In providing its advice to the ATCM, the CEP must attempt to reach consensus, but in cases where this cannot be achieved, the Committee's report must set out all views expressed on the matter in question.

The CEP is informally led by the CEP Bureau, comprising the CEP Chair and the first and second Vice-Chairs and supported by a representative of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. The CEP meets every year in conjunction with the ATCM. The meeting commences before the ATCM, so that the CEP's advice from its meeting, in the form of a report, can be considered during the ATCM. The Committee's discussions are guided by the CEP Five-Year Work Plan, which focuses on high-priority environmental issues, including 1) management of risks associated with species not native to Antarctica, 2) management of environmental impacts of tourism and non-governmental activities, 3) understanding and responding to the environmental consequences of climate change in the Antarctic region and 4) improving the effectiveness of protected area management and enhancing the protected area system (see below). The Committee also uses management tools agreed under the Protocol to reduce future potential environment impact, such as through the EIA process, the designation of protected areas and the designation of specially protected species (SPS). CEP Members engage year-round in task-orientated activities, including through its Subsidiary Group on Climate Change Response (SGCCR) and Subsidiary Group on Management Plans (SGMP).

The CEP is an advisory body rather than a scientific body, but it has identified science needs that could be fulfilled by the Antarctic science community (see https://documents.ats.aq/ATCM43/att/ATCM43_att054_e.docx). In general, the CEP receives science knowledge from Parties or scientific organizations, such as SCAR or WMO, via Working Papers, Information Papers and Background Papers submitted to the CEP meeting. The CEP meeting reports are available on the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat website, along with the papers submitted to the meetings by CEP Members and Observers (see https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e).

Meetings: Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

CCAMLR and its Scientific Committee (SC-CAMLR) were established in 1982 once the CAMLR Convention had entered into force. The objective of the Convention is the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources, and for the purposes of the Convention the term ‘conservation’ includes rational use. The function of the Commission is to give effect to the objectives and principles set out in the Convention. To achieve this, the Scientific Committee provides the best available scientific information to the Commission, which then forms the basis for the latter to agree Conservation Measures that determine the use of marine living resources in the Antarctic.

CCAMLR membership is open to any Contracting Party engaged in research and/or harvesting activities related to the marine living resources that the Convention applies to. Acceding States are Contracting Parties that are not Members (i.e. they do not take part in research or harvesting activities), and they do not take part in decision-making. All Members of the Commission are also Members of the Scientific Committee. There are currently 27 CCAMLR Members and 10 Acceding States. Decisions of the Commission are generally taken by consensus of the CCAMLR Members.

The Commission Chair rotates alphabetically through the Parties, while the Chair and Vice-Chair of the Scientific Committee are elected from among its Members. The CCAMLR Secretariat, headed by the Executive Secretary, is located in Hobart, Australia, and supports both the Commission and the Scientific Committee. The Commission has also established two subsidiary bodies: the Standing Committee on Implementation and Compliance (SCIC) and the Standing Committee on Administration and Finance (SCAF). The Commission meets annually in Hobart, usually during October. The Scientific Committee meets immediately prior to the Commission meeting each year, and the Standing Committees meet during the Commission meeting. Working Groups of the Scientific Committee also meet at other times during the year to undertake technical and scientific work on specific topics as necessary. Observers do not attend Working Group meetings, although Working Groups can invite specific experts to participate as needed.

At meetings of CCAMLR and SC-CAMLR, Working Papers and Background Papers can be submitted. Working Papers, which contain recommendations, can only be submitted by Members. CCAMLR can also receive scientific information in the form of Background Papers submitted by invited Observers, including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), SCAR, the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR; i.e. via the Southern Ocean Observing System; SOOS), ACAP and IWC.

The Scientific Committee incorporates research from the National Antarctic Programmes of CCAMLR Members when providing advice to the Commission, but it is also capable of including expert scientific opinion from outside these programmes should the need arise. Importantly, while the role of SCAR is enshrined in the Articles of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, it does not have a mandated role within the CAMLR Convention and serves as an Observer only (although the Scientific Committee can and does make specific requests of SCAR when needed). CCAMLR has also established a number of its own data collection programmes, including monitoring of fisheries, ecosystems and marine debris and providing scientific observers on fishing vessels. CCAMLR is focused on topics relating to the marine living resources under its jurisdiction, including stock or population assessments and information regarding harvesting, monitoring, conservation and management. To facilitate and organize this work, the Scientific Committee has established several Working Groups on key topics: ecosystem monitoring and management (WG-EMM), fish stock assessment (WG-FSA), statistics, assessments and modelling (WG-SAM), incidental mortality associated with fishing (WG-IMAF) and acoustics, survey and analysis methods (WG-ASAM). Reports for the Commission and its Standing Committees, the Scientific Committee and its Working Groups are all available online via the CCAMLR website (https://www.ccamlr.org/en/meetings); however, not all meeting documents are publicly available given the commercial-in-confidence nature of some of the data used.

Meetings: Meeting of Parties to the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels

The Meeting of the Parties is the decision-making body of ACAP. In general, decisions of the Meeting are determined by consensus, although if consensus cannot be achieved, then they are taken by a two-thirds majority of present and voting Parties. Some decisions, as in accordance with Article VIII of the Agreement, are adopted only by consensus.

Ordinary Sessions of the Meeting of the Parties are normally held around April–May every 3 years, and Extraordinary Sessions can be requested if required. An Advisory Committee was established at the first Meeting of the Parties to provide expert advice to the Parties and Secretariat. The Advisory Committee and Working Groups often meet in the intervening years between Ordinary Sessions of the Meeting of the Parties.

ACAP generally produces information about albatrosses and petrels for external bodies, such as CCAMLR, to utilize. ACAP also funds relevant research via a small grants programme. ACAP is interested in any issues involving ACAP species globally. Current Working Groups include groups focused on seabird bycatch, population and conservation status and taxonomy. Meeting reports and documents for the Meeting of the Parties, Advisory Committee and Working Groups are available on the ACAP website (https://www.acap.aq/).

Meetings: International Whaling Commission

The IWC was established under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (Gales Reference Gales2022) and has 88 Members countries. It is a global organization and not part of the ATS, but its area of jurisdiction encompasses the Southern Ocean. The IWC first met in 1950 and is an inter-governmental organization whose purpose is the conservation of whales and the management of whaling. The IWC agreed a whaling moratorium, which came into force in 1985 (although it does allow for some whaling for scientific research purposes). In the early twentieth century, whaling decimated cetacean populations, with > 2 million individuals taken from the Southern Ocean. In 1994, the IWC designated the entire Southern Ocean as a whale sanctuary. Increasing stock numbers make whales important higher predators within the Southern Ocean ecosystem and, therefore, relevant to the work of CCAMLR. Recognizing the interests shared by CCAMLR and the IWC, each organization sends scientific observers to the other's meetings, and several joint workshops have been hosted to resolve scientific issues of joint interest. Decisions of the IWC are taken by a simple majority of its Members' voting, except that a three-quarters majority of those Members' voting is required for actions concerning the conservation and utilization of whale resources.

The full meetings of the Commission occur every 2 years. Those attending the meetings include the representatives of contracting countries to the Convention, Observers from non-Member governments, other inter-governmental organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The work of the Commission is divided between a number of Committees and Working Groups that operate intersessionally and report progress and make recommendations to the biennial meeting of the Commission.

Predominantly through its Scientific Committee, the Commission facilitates and coordinates extensive research on cetacean populations. The Scientific Committee comprises ~200 cetacean scientists from many countries, the majority of whom attend the Scientific Committee's annual meeting. The IWC is concerned with cetacean conservation and welfare concerns, including bycatch and entanglement, ship strikes and whale watching. The Conservation Committee works with the Scientific Committee on environmental and conservation issues, develops Conservation Management Plans and receives proposals for new whale sanctuaries. Other areas of environmental concern relevant to cetaceans include climate change, ocean noise, marine debris, chemical pollution, disease and marine renewable energy developments. The Commission makes reports and documents available on its website, including those from Commission Meetings, as well as a data portal and a historical database (https://iwc.int/documents).

Stakeholders: Parties/Members

The states that have an interest in Antarctic affairs comprise the membership of the key bodies that manage or coordinate different aspects of Antarctic governance, science and logistics. The nations that are signatories to the various instruments of the ATS are commonly referred to as ‘Parties’ or ‘Members’. Parties, in general, provide a logistical and scientific presence in Antarctica through their National Antarctic Programme. Each Party's national competent authority (usually within a government department or ministry) is responsible for ensuring that the actions of organizations (including tourism and fishing companies) and individuals falling under their jurisdiction comply with the requirements of the ATS (Joyner Reference Joyner1998). For example, Parties, through their respective competent authority, ensure that EIA requirements are undertaken and adhered to and issue permits to undertake otherwise prohibited activities within the region. Parties are also responsible for putting ATS agreements into their domestic legislation, thereby providing a legal basis upon which to put them into effect (Bastmeijer Reference Bastmeijer2003b).

Stakeholders: Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research

SCAR was formed in 1958 and is an affiliated body and thematic organization of the International Science Council (ISC). SCAR's two major aims are 1) to ‘initiate, develop and coordinate high quality international scientific research in the Antarctic region (including the Southern Ocean), and on the role of the Antarctic region in the Earth system’ and 2) to ’provide objective and independent scientific advice to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings and other organisations on issues of science and conservation affecting the management of antarctica and the Southern Ocean and on the role of the Antarctic region in the Earth system’.

SCAR membership includes ISC-affiliated national scientific academies or research councils of countries that are active in Antarctic research, as well as nine relevant Unions of the ISC. There are currently 34 full and 12 associate Member countries. Members are represented at SCAR meetings by National Delegates. SCAR is governed by its constitution, the Articles of Association (https://www.scar.org/about-us/governance/). Decisions taken at biennial meetings of the Members require unanimity of participating Members. SCAR Delegates determine SCAR's priorities and directions, while the SCAR Executive Committee executes the Delegates’ decisions, supported by the SCAR Secretariat and the leaders of SCAR's subsidiary groups (see https://www.scar.org/about-us/leaders/). The SCAR Secretariat is based at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK.

SCAR is primarily a scientific body, with many of its scientific outputs generated by its subsidiary groups. The three permanent Science Groups, representing the physical sciences, life sciences and geosciences, and the Standing Committee on the Humanities and Social Sciences (SC-HASS) establish Expert Groups and Action Groups to address specific research topics within the discipline. Scientific Research Programmes are broad, often interdisciplinary programmes with research focused on high-priority areas or issues. Standing Committees have been formed to manage finances, data and geographical information. The Standing Committee on the Antarctic Treaty System (SCATS) is the body tasked with developing and delivering SCAR's scientific advice to the ATCM, CEP, CCAMLR and ACAP or other policy bodies as relevant.

SCAR is interested in all Antarctic research, including the social sciences and the role of Antarctica in the Earth system. In recent years, SCAR has provided science summaries to the ATCM and/or CEP on a diverse range of topics, including the conservation status of SPS, the designation of protected areas, pollution, wildlife disturbance, non-native species, ocean acidification and climate change. SCAR has also undertaken a horizon scan to identify future priorities for Antarctic science, which included research to further recognize and mitigate human influences (Kennicutt et al. Reference Kennicutt, Chown, Cassano, Liggett, Massom and Peck2014). Reports submitted to the SCAR Delegates Meetings, including reports from the Science Groups, Scientific Research Programmes and Standing Committees, can be found on the SCAR website (https://www.scar.org/excom-meetings/).

Stakeholders: Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs

COMNAP was established in 1988 and aims to ‘develop and promote best practice in managing the support of scientific research in Antarctica’. It achieves this by providing opportunities for international knowledge exchange and discussion, facilitating international partnerships and developing practices to increase the effectiveness of Antarctic activities within a sustainable framework. It also provides the ATS with advice based on the joint expertise of COMNAP Members. Members of COMNAP are the National Antarctic Programmes of Antarctic Treaty Parties. There are currently 33 COMNAP Members and five Observers (i.e. expert organizations that provide technical information or knowledge but do not participate in decision-making). Decisions at meetings are generally taken by consensus of the Members.

COMNAP is led by an Executive Committee, elected from COMNAP Members, and is supported by the COMNAP Secretariat, headed by the Executive Secretary, which is currently based in Christchurch, New Zealand. COMNAP generally meets at least once per year, with the annual general meeting hosted by a Member country. COMNAP Symposiums are held biennially, normally on the margins of the Annual General Meeting.

COMNAP is not a scientific body but supports and facilitates scientific research. COMNAP facilitates information exchange and generates information for the CEP, ATCM and National Antarctic Programmes, providing objective, practical, technical and non-political advice. This information may be on issues of interest to COMNAP or in response to requests from the ATCM. Generally, this information concerns operational information and best practice for managing scientific research support (Nuttall Reference Nuttall, Nuttall, Christensen and Siegert2018). Currently, COMNAP has Expert Groups concerned with advancing critical technologies, air operations, education outreach and training, environmental protection, human biology and medicine, marine platforms, safety and science facilitation. COMNAP workshop and symposium reports are available on its website (https://www.comnap.aq/symposiums-workshops-reports).

Stakeholders: World Meteorological Organization

The WMO was established by the ratification of the Convention of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO Convention) in 1950. It is the specialized agency of the UN for meteorology (weather and climate), operational hydrology and related geophysical sciences. It is an intergovernmental organization with a membership of 193 Member States and Territories. The World Meteorological Congress is the decision-making body of the WMO. The WMO Executive Council implements the decisions of the Congress, while six Regional Associations are responsible for the coordination of activities within their respective Regions. In general, decisions of the Congress and Executive Council are made by a two-thirds majority of the votes cast. The Secretariat has its headquarters in Geneva. The Congress meets every 4 years to review and give policy guidance to WMO Programmes. The Executive Council meets annually and monitors the implementation of decisions taken by Congress. Regional Associations meet biennially to define regional priorities and activities.

The WMO is a leading research body with very broad research interests, including natural hazard and disaster reduction, the environment (including ozone, greenhouse gases, aerosols and atmospheric composition and deposition), the cryosphere (including its Panel on Polar and High Mountain Observations, Research and Services and the Global Cryosphere Watch), oceans (including as a driver of the world's weather, climate and climate change), energy and urban issues. A wide range of documents are available from the WMO resources library (https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/library). WMO is an Invited Expert to the ATCM and CEP.

Stakeholders: Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition

The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) was founded in 1978 in response to the growing interest in mineral and gas prospecting in Antarctica. ASOC is an NGO that works to protect the Antarctic for all of humanity through advocacy and campaigning. ASOC is the only NGO dedicated wholly to Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. ASOC advocates for science-based policymaking and responsibly managing human activities. The ASOC Coalition consists of over 15 conservation organizations, including the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Conservation International, Greenpeace and the Pew Charitable Trusts. ASOC also works with two partner organizations: the IUCN and Blue Nature Alliance. ASOC is governed by a Board of Directors, who are elected from the Coalition Members. The ASOC secretariat is led by an Executive Director and supported by a number of international campaigners whose expertise helps to inform ASOC recommendations to Antarctic Treaty Parties.

ASOC supports science-based policies in Antarctic Treaty decision-making. ASOC collaborates with science and industry, which provide a direct source of relevant information to ASOC. Many of ASOC's international campaigners and Members are also experts in various aspects of Antarctic research, and this expertise also feeds into ASOC's science-based policy proposals that they present at ATCM and CCAMLR meetings. ASOC is interested in all issues related to protecting and conserving Antarctic and Southern Ocean environments and species into the future. Current campaigns revolve around climate change, protecting Antarctica and responsible tourism and fisheries management. ASOC submissions to the ATCM can be found in the meeting archives on the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat website (https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/DocDatabase?lang=e), and ASOC media releases are available on the ASOC website (https://www.asoc.org/news/).

Stakeholders: International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators

The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) was founded in 1991 by seven tour operators who were already operating in the Antarctic (Palmowski Reference Pannatier2020). IAATO's primary aim is to advocate and promote the practice of safe and environmentally responsible private-sector travel to the Antarctic. IAATO operates within the parameters of the ATS, including that tourism should have no more than a minor or transitory impact on the Antarctic environment, as well as fostering cooperation between their Members. IAATO is an Invited Expert to the ATCM and CEP and an Observer to CCAMLR.

IAATO is a membership organization composed of Operators and Provisional Operators, as well as of Associate Members who do not operate directly in the Antarctic but are often tour operators or agents who book their clientele into Operator Member programmes. There are currently more than 50 Operators and Provisional Operators and just over 50 Associate Members. Operators in ‘good standing’ are eligible to vote, and decisions taken by vote require a two-thirds majority of the votes to pass. IAATO is led by the Executive Committee and Secretariat. The Executive Committee consists of Operator Members and acts on behalf of the Membership, including decision-making on behalf of the Membership when appropriate. The Executive Director runs the organization with support from other members of the Secretariat. Standing Committees and Working Groups are also established by the membership to address ongoing or specific issues. IAATO holds an Annual Meeting, and Extraordinary Meetings may be scheduled by Members as required.

IAATO is not a scientific body but supports science and has collaborated with and occasionally funded scientists to generate information useful to decision-makers and IAATO on issues relevant to Antarctic tourism. Outputs from these collaborations may form the basis of Information Papers that IAATO submits to the ATCM. Some IAATO Operators also support citizen science projects. IAATO Annual Meeting reports are not publicly available, although they do submit a report as an Information Paper to the ATCM each year. These reports and other IAATO submitted Information Papers are available on the IAATO website (https://iaato.org/information-resources/data-statistics/iaato-atcm-information-papers/).

Stakeholders: Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies

The Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies (ARK) is the industry body for krill-harvesting companies and was founded in 2012. ARK's mission is to facilitate an industry contribution to an ecologically sustainable krill harvest. Its primary goal is to develop practices for the long-term sustainability of the krill fishery and its dependant predators (Godø & Trathan Reference Godø and Trathan2022). ARK membership comprises eight krill-fishing companies from four CCAMLR Member countries. The total fishing capacity of ARK Members represents > 90% of all krill catches within the CAMLR Convention area. In addition to the mandated reporting of catch by flag states under the Convention, ARK Members provide additional data to CCAMLR and facilitate research on krill and the krill fishery. They actively promote cooperation with the scientific community, including SCAR and SC-CAMLR. ARK reports are available from https://www.ark-krill.org/repository.

Stakeholders: Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators

The Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators (COLTO) was founded in 2003 by legal industry members to eliminate illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing for toothfish and to ensure the long-term sustainability of toothfish resources and the rich and critical biodiversity of the southern oceans (Österblom & Sumaila Reference Österblom and Sumaila2011). The missions of COLTO are 1) to promote sustainable toothfish fishing and fisheries and remain vigilant against IUU fishing, 2) to facilitate its Members working together and with others, including through the continued provision of high-quality scientific data to CCAMLR and other bodies, and 3) to provide effective representation for its Members. COLTO has 50 Members from 12 countries. The total fishing capacity of COLTO members represents 80–85% of all toothfish catches.

COLTO has a Working Group on Science Cooperation that aims to raise awareness of the existing contribution made by COLTO Members to scientific research and to identify future science projects to which COLTO could make a valuable contribution. COLTO Members’ vessels are used to collect data that contribute to scientific research programmes, including science that supports the sustainable management of toothfish fisheries and the collection of oceanographic data. COLTO is interested in practical methods to reduce incidental mortality of seabirds and in methods to educate consumers about sustainable toothfish fishing. It also investigates depredation (removal of fish caught on fishing lines) by toothed whales, which can lead to economic losses for its Members, increased pressure on toothfish stocks and injury or mortality to whales (Tixier et al. Reference Tixier, Burch, Massiot-Granier, Ziegler, Welsford and Lea2020). COLTO has hosted industry-science workshops to progress some of these issues.

Stakeholders: other bodies providing expert advice to one or more meetings of the Antarctic Treaty System

Other bodies with relevant environmental, scientific or technical expertise may be invited to contribute as experts to the ATCM and CEP, including the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the International Group of Protection and Indemnity Clubs (IGP&I Clubs; who provide liability cover for ocean-going shipping), the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), the IMO, the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (IOPC Fund), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the IUCN, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

Engagement in the work of Antarctic Treaty System

Parties can participate in governance bodies through, for example, attendance at or hosting of meetings, participation in intersessional work (including via Subsidiary Groups or Working Groups), taking on leadership roles such as meeting Chair or Vice-Chair or submission of papers to meetings. A further way to show engagement in governance includes the funding of research activities that respond to current issues within Antarctica, with a recent example being the Dutch Research Council and Government Ministries funding new projects to investigate tourism in Antarctica (‘Polar Tourism - Research Programme on Assessment of Impacts and Responses’; see https://www.nwo.nl/en/news/four-new-projects-about-antarctic-tourism). Such examples are not common, but further purposeful consideration of funding opportunities for policy-relevant science would greatly enhance international policy development and protection of the Antarctic environment. With this in mind, decision-makers should consider how to better communicate their science needs to national research funding agencies as the organizations in a position to provide resources to support policy-relevant research (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Constable, Frenot, López-Martínez, McIvor and Njåstad2018).

The level of engagement by individual Parties and organizations differs greatly across the various meetings and even between individual agenda items discussed at those meetings. The level of paper authorship/co-authorship is one rather crude metric by which meeting participants’ degree of engagement can be quantified (Dudeney & Walton Reference Dudeney and Walton2012). For example, Fig. 4 shows the total number of papers authored or co-authored by each eligible participant of the ATCMs and CEP meetings between 2012 and 2022 (representing the last 10 years when meetings were held; no meeting was held during 2020 as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic; Hughes & Convey Reference Hughes and Convey2020). Figure 5 shows the total number of papers authored by participants in the meetings of SC-CAMLR between 2012 and 2022; however, it should be noted that further papers, many of which are based on scientific outputs, are also submitted to the CCAMLR Working Groups (e.g. WG-EMM and WG-FSA), where substantial scientific discussions occur and where the contributions of many researchers are focused. The outputs of the Working Groups inform the advice of the Scientific Committee to CCAMLR. As a result, the Working Groups have been described as the engine room for science translation in the CCAMLR system. Levels of paper authorship by Parties and organizations vary greatly and may be a product of 1) the degree of meeting experience gained, 2) the extent of resources available to develop new work or report information, 3) the degree of cooperation with other Parties and organizations also submitting papers and 4) the level of interest and available expertise relevant to the wide range of issues that fall under the remit of the different international agreements. For example, some Parties may have a greater interest in issues relevant to activities in the vicinity of their area of Antarctic operation (e.g. around research stations) or in issues where they have existing expertise (e.g. tourism management or area protection).

Figure 4. The total number of Working Papers, Information Papers and Background Papers authored by participants of the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings and Committee for Environmental Protection meetings between 2012 and 2022. ACAP = Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels; ARK = Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies; ASOC = Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition; CCAMLR = Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; COLTO = Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators; COMNAP = Council of Mangers of National Antarctic Programs; IAATO = International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators; ICAO = International Civil Aviation Organization; IGP&I Clubs = International Group of Protection and Indemnity Clubs; IHO = International Hydrographic Organization; IMO = International Maritime Organization; IOPC Fund = International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund; IPCC = Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IUCN = International Union for Conservation of Nature; IWC = International Whaling Commission; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research; UNEP = United Nations Environment Programme; UNWTO = United Nations World Tourism Organization; WMO = World Meteorological Organization.

Figure 5. The total number of papers authored by participants in the meetings of the Scientific Committee of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (SC-CAMLR) between 2012 and 2022. No papers were submitted by Acceding States to the CAMLR Convention during the reporting period (i.e. Bulgaria, Canada, Cook Islands, Finland, Greece, Mauritius, Pakistan, Panama, Peru and Vanuatu). Ecuador became a full Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) Member in 2022 and submitted one paper in 2021 and one paper in 2022. ACAP = Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels; ARK = Association of Responsible Krill harvesting companies; ASOC = Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition; CEP = Committee for Environmental Protection; COLTO = Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators; FAO = Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; IAATO = International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators; IUCN = International Union for Conservation of Nature; IWC = International Whaling Committee; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research; SCOR = Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research; SOOS = Southern Ocean Observing System; WWF = World Wildlife Fund.

Some non-Consultative Parties who aspire to achieve consultative status under the Antarctic Treaty may make a greater effort to submit papers to provide evidence of active engagement in Antarctic governance, which they could potentially use to support their case for consultative status (Gray & Hughes Reference Gray and Hughes2016, Xavier et al. Reference Xavier, Gray and Hughes2018, Feride et al. Reference Feride, Uzun, Ager, Convey and Hughes2023). Notably, SCAR has routinely provided information on a wide range of topics over many decades; it has submitted 137 papers to the ATCMs and CEP meetings since 2012, making it one of the most active organizations in terms of paper submissions and engagement in policy discussions (alongside, e.g., ASOC, COMNAP and IAATO; see Figs 4 & 5).

The role of science in informing Antarctic governance

Antarctica is unique in that the continent and surrounding ocean is predominantly governed and managed through an international arrangement: the ATS (Barrett Reference Barrett, Scott and VanderZwaag2020). The ATS was founded upon the principle and practice of international cooperation in scientific research and the promotion of freedom of scientific investigation. Furthermore, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty designates the area south of latitude 60°S (the Antarctic Treaty area) as a ‘natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’ (see Fig. 2). Science is therefore a vital activity within the Antarctic Treaty area, albeit one that is closely entwined with promoting national interests (Yao Reference Yao2021). Within this context, Antarctic researchers fulfil several key roles, as will be discussed in the following subsections.

Supporting national priorities and interests (science diplomacy)

Scientific research activity within Antarctica is important for Parties to the Antarctic Treaty to demonstrate their scientific credentials, as a prerequisite for full participation in the governance arrangements for Antarctica (Pannatier Reference Pannatier1994, Elzinga Reference Elzinga, Berkman, Lang, Walton and Young2011). Specifically, to acquire consultative status, an interested Party must demonstrate ‘substantial scientific research activity’ within the Treaty area, although no agreed mechanism exists to precisely determine whether a Party has fulfilled this criterion (although see Gray & Hughes Reference Gray and Hughes2016, ATS 2017). Therefore, the work of a Party's Antarctic research community is central to supporting their nation's existing or potential future entitlement to participate in the governance of the region as a Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty.

Delivery of fundamental research of global relevance

Each year, nations active in Antarctica invest many hundreds of millions of dollars to support research, and several thousand researchers and support personnel travel to the Antarctic to undertake this work (Chown Reference Chown2018, Nuttall Reference Nuttall, Nuttall, Christensen and Siegert2018). Antarctic research has been fundamental to advancing our knowledge across many academic disciplines ranging from astronomy to zoology (Fu & Ho Reference Fu and Ho2016). In recent years, research effort has focused on climate change impacts on southern polar systems and the potential implications of these changes for the rest of the globe, including impacts upon ocean circulation, weather patterns and sea level (Siegert et al. Reference Siegert, Atkinson, Banwell, Brandon, Convey and Davies2019, Chown et al. Reference Chown, Leihy, Naish, Brooks, Convey and Henley2022).

Informing Antarctic decision-making

Decision-makers within the ATS frequently employ the term ‘best available science’ to qualify the scientific basis for making policy decisions (Goldsworthy Reference Goldsworthy2022a). The growing quantity and distribution of human activities and the spatially heterogeneous impacts of climate change across the region (Tin et al. Reference Tin, Fleming, Hughes, Ainley, Convey and Moreno2009, Chown & Brooks Reference Chown and Brooks2019) mean that decision-makers increasingly rely upon applied research (i.e. research that seeks to address practical problems). It is thus unsurprising that decision-makers are taking steps to communicate their science needs to researchers, including for the protection of the Antarctic environment (McIvor Reference McIvor2020). Furthermore, the Protocol acknowledges the important role played by the scientific community, and SCAR in particular, in contributing to further shaping Antarctic environmental policies (see Article 12(2): ‘In carrying out its functions, the Committee shall, as appropriate, consult with the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, the Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources and other relevant scientific, environmental and technical organizations’). Engagement by researchers in communication at the science-policy interface is therefore essential (Gilbert & Njåstad Reference Gilbert and Njåstad2015). Through wise and effective management of Antarctica, the research values of the region will be preserved, which will allow the continued conduct of globally relevant research. Indeed, protection of the value of Antarctica as an area for the conduct of scientific research is a core principle of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty.

Provision of science to support commercial interests

Scientific activities within the Antarctic Treaty and CAMLR Convention areas may include research to support potential commercial interests. For example, research may inform fish stock assessments that contribute to the establishment of catch limits for areas within the Southern Ocean. Whilst Article 7 of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty states that ‘[a]ny activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research, shall be prohibited’, it appears that some Parties have apparently undertaken mineral prospecting. For example, in 2011, the Russian Federation declared to the ATCM its intention to ‘strengthen the economic capacity of Russia through the … complex investigations of the Antarctic mineral, hydrocarbon and other natural resources’, and this was put into apparent action through marine seismic surveys for hydrocarbons, reported in 2020 and 2023 (Russian Federation 2011, Watkins Reference Watkins2020, Afanasiev & Esau Reference Afanasiev and Esau2023). A number of National Antarctic Programmes also support research examining the commercial application of Antarctic biological material (biological prospecting), and SCAR has surveyed its Member countries to assess the extent to which bioprospecting has been undertaken through National Antarctic Programmes (SCAR 2021a, Silva et al. Reference Silva, Feitosa, Lima, Bispo, Santos and Moreira2022).

Communication at the science-policy interface: benefits to researchers

Engaging with decision-makers has benefits for Antarctic researchers, as in other disciplines (Evans & Cvitanovic Reference Evans and Cvitanovic2018, Sokolovska Reference Sokolovska, Fecher and Wagner2019). At the most basic level this represents an improved understanding of how a researcher's work fits into the broader policy and political context. For those undertaking applied research, it provides a mechanism by which the value of that work may be understood and potentially lead to identifiable changes in policy and/or management practices. It could be considered that undertaking applied research without an identified route map for policy impact is a wasted opportunity (Dilling & Lemos Reference Dilling and Lemos2011). Co-production of policy outputs (i.e. the generation of outputs that involve all stakeholders at each stage of the knowledge-acquisition and decision-making process) provides evidence of the policy relevance and impacts of research, which may subsequently act to raise the profile of research institutes and help to secure future research funding (Wyborn et al. Reference Wyborn, Datta, Montana, Ryan, Leith and Chaffin2019). Having a broader understanding of the policy context of an individual's research can also enhance personal development and provide opportunities to build communication skills at the science-policy interface, as well as a broader profile. In turn, this knowledge may prepare individuals to be suitable for a wider range of roles, and it could provide a strategic advantage when applying for a new position or promotion.

Topics of policy interest for which research may inform decision-making

To arrive at an agreed course of action that will address an identified problem or issue, decision-makers will draw on available information to inform their decision-making processes. Decision-makers may take into consideration existing precedents and the precautionary approach (Bastmeijer & Roma Reference Bastmeijer and Roma2004). However, decision-makers are increasingly accessing and using the best available science to inform their work, while at the same time accounting for the level of uncertainty in that information. The CEP has made efforts to identify the science needed to inform its work (see https://documents.ats.aq/ATCM43/att/ATCM43_att054_e.docx; see also Australia 2017), while SC-CAMLR has held symposiums to set out its priorities and scientific 5 year work plans. The 2022 Scientific Report set out priority research topics and tasks for each Working Group, including data collection requirements and intersessional science work plans (see https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/sc-camlr-41). At a higher level, the CCAMLR Performance Reviews have set out scientific priorities (CCAMLR 2019).

Research outputs that inform policy can take many forms and can range from single research papers to large-scale research syntheses. Tables II–IV set out selected items on the agendas of the ATCM, CEP and SC-CAMLR, respectively, and they provide examples of relevant peer-reviewed research that has been published and, in some cases, presented to the relevant policy body. Further specific examples are provided below for the ATCM, CEP and SC-CAMLR.

Table II. Science and policy work relevant to selected Agenda Items of the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM).

COMNAP = Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs; EIES = Electronic Information Exchange System; ICG = Intersessional Contact Group; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.

Table III. Science and policy work relevant to selected agenda items of the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP).

ASOC = Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition; EIA = environmental impact assessment; HSM = Historic Site and Monument; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.

Table IV. Science and policy work relevant to selected agenda items of the Scientific Committee of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (SC-CAMLR).1

1 SC-CAMLR meeting papers are not always publicly available; however, their titles are provided on the CCAMLR website, and copies can be requested at the discretion of the authors (as opposed to CCAMLR itself).

CCAMLR = Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; IUU = illegal, unregulated and unreported; NA = not applicable.

ATCM

SCAR plays a key role in the provision of science syntheses to Antarctic decision-makers concerning climate change (including information of relevance to the IPCC or the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)). A recent example of this is the SCAR report ‘Antarctic Climate Change and the Environment: A Decadal Synopsis and Recommendations for Action’, which synthesised research on the trajectory and impacts of climate change in Antarctica based on knowledge provided by researchers and previous IPCC syntheses (Chown et al. Reference Chown, Leihy, Naish, Brooks, Convey and Henley2022). SCAR papers to the ATCM and CEP provided a summary of the key findings from the report and a series of policy recommendations derived from these findings, including that countries meet or exceed the greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets of the Paris Climate Agreement in order to maintain the Antarctic and Southern Ocean in a state close to that known for the past 200 years (SCAR 2022a, 2022b). In response, the ATCM agreed to hold a joint ATCM/CEP full-day session during the ATCM and CEP meetings in Helsinki, Finland (2023), to consider the implementation of the recommendations of the SCAR report. The report was also submitted for consideration at SC-CAMLR in 2022, and, alongside climate change papers submitted by several other meeting participants, this resulted in a new climate change Resolution and a workshop on climate change in 2023 (CCAMLR 2022, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Cavanagh and Convey2022a).

Many academic researchers study the effectiveness of Antarctic governance and the mechanisms available to deliver policy and subsequent management (e.g. Bastmeijer Reference Bastmeijer2018, Lord Reference Lord2020, Flamm Reference Flamm2022). Specific examples may include research and commentary on liability arising from environmental emergencies (e.g. Ijaiya Reference Ijaiya2017, Hemmings Reference Hemmings2018), tourism management (Kruczek et al. Reference Kruczek, Kruczek and Szromek2018, Carey Reference Carey2020, Tejedo et al. Reference Tejedo, Benayas, Cajiao, Leung, De Filippo and Liggett2022), inspections under the Antarctic Treaty (Tamm Reference Tamm2018) and biological prospecting (Heinrich Reference Heinrich2020, Haward Reference Haward2021). It may be difficult to map how this research influences Antarctic policy, particularly at a time when no new major legal instruments are being revised or developed; however, such research will be essential as existing legal agreements attempt to meet the environmental and geopolitical challenges of the twenty-first century (Liggett et al. Reference Liggett, Frame, Gilbert and Morgan2017, Ferrada Reference Ferrada2018, Roberts Reference Roberts2020, Yermakova Reference Yermakova2021).

CEP

There are many examples of academic research directly influencing the work of the CEP. Research that divided the Antarctic terrestrial environment into distinct eco-regions (termed Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions; ACBRs) was recognized by the CEP as a useful model for the identification of areas that could be designated as Antarctic Specially Protected Areas within a systematic environmental-geographical framework (Australia et al. 2012, Terauds et al. Reference Terauds, Chown, Morgan, Peat, Watts and Keys2012, Terauds & Lee Reference Terauds and Lee2016). The model was subsequently endorsed by the ATCM through Resolution 6 (2012) and Resolution 3 (2017). In another example, published work by UK and Spanish researchers formed the basis for a paper submitted to the CEP that provided a non-native species response protocol (Hughes & Pertierra Reference Hughes and Pertierra2016, United Kingdom & Spain 2017). Following further consideration and revision by CEP Members, the response protocol was agreed and added to the CEP Non-native Species Manual (CEP 2019).

In 2021, SCAR submitted two papers to the CEP that reported their review of the conservation status of the emperor penguin (SCAR 2021b, 2021c). The review concluded that the emperor penguin is increasingly vulnerable due to the loss of its fast-ice breeding habitat. The CEP proceeded to draft an Action Plan for the conservation of the emperor penguin, but designation as an Antarctic SPS has not yet been agreed. In a final example, a synthesis paper produced by Hodgson & Koh (Reference Hodgson and Koh2016) concerning best practice for minimizing drone disturbance to wildlife in biological field research was presented to CEP XX by SCAR (SCAR 2017), which subsequently contributed to the production of the ‘CEP environmental guidelines for operation of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) in Antarctica’; Resolution 4 (2018); https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/Measure/679).

SC-CAMLR

In the context of SC-CAMLR, the work of named individuals or groups of researchers is regularly submitted to meetings for consideration. CCAMLR does not always make these papers publicly available, although titles as well as summaries of the discussions of each paper presented are listed in each SC-CAMLR report (e.g. https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/sc-camlr-41), and all submitted Working Papers can be requested through the CCAMLR Secretariat once approval from the authors has been given. Examples of research submitted to SC-CAMLR include a synthesis paper by Teschke et al. (Reference Teschke, Pehlke, Siegel, Bornemann, Knust and Brey2020) that provided a systematic overview of all data sources collected in the context of the Weddell Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) planning process (included abiotic data, such as bathymetry and sea ice, and ecological data from zooplankton, zoobenthos, fish, birds and marine mammals). Discussions on the development of the new CCAMLR krill fishery management strategy were informed by the production of many academic papers that have subsequently supported numerous papers to CCAMLR (often co-authored by several Parties and/or Observers and Experts), addressing spatial subdivision of krill catch, predator distribution and predator consumption.

Mechanisms by which researchers may engage in science-policy communication

Here we describe how Antarctic researchers, science coordinating bodies and decision-makers can work together to advance the objectives of the international agreements relevant to the Antarctic region, including via the ATCM, CEP and CCAMLR. It is worth noting that researchers working within National Antarctic Programmes may engage in long-term monitoring, ecosystem modelling or climate modelling that may act as the foundation for more policy-targeted work to fulfil ATCM and CCAMLR objectives. The delivery of directed policy-relevant information by these researchers may facilitate the development of strong relationships with decision-makers. In contrast, while it may be more challenging for researchers with less direct involvement with policy forums to bring their work to the attention of decision-makers, it is important that efforts are made to ensure other research information, including details of emerging issues, is effectively communicated.

It is recognized that levels of experience and exposure to policy differ greatly amongst researchers, and in Table V we provide example profiles of researchers located at different points along the science-policy communication continuum (Safford & Brown Reference Safford and Brown2019). Readers are invited to identify which profile they consider themselves to most closely resemble and, where relevant, to consider engaging with opportunities to become more involved.

Table V. Example profiles of researchers located at different points along the science-policy communication continuum.

Ant-ICON = SCAR Scientific Research Programme ‘Integrated science to inform Antarctica and Southern Ocean conservation’; ATS = Antarctic Treaty System; SCAR = Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research; SCATS = SCAR Standing Committee on the Antarctic Treaty System.

Mentors

As a general point, researchers wishing to engage in science-policy communication may benefit from identifying and working with existing researchers who already work across the science-policy interface. Such individuals may already have 1) developed deep knowledge, 2) built extensive networks and 3) participated in the ATS for extended periods of time, making them well placed to help others deliver policy impacts from their research (Weible et al. Reference Weible, Heikkila, DeLeon and Sabatier2012). Researchers may like to consider whether there is anyone within their own organization or institute or within their network of collaborators who might be able to help. Help may be available outside a researcher's organization, such as within the relevant national Antarctic research committee, which is the body that represents national interests to SCAR (see https://www.scar.org/about-us/delegates/).

Direct communication with decision-makers

The most direct method for researchers to engage in science/policy communication is often for them to liaise directly with government representatives within their National Delegations to ATS meetings. The small size of the Antarctic community means that there may be significant opportunities to build relationships with relevant decision-makers, and the importance of building these relationships should not be underestimated (Brisbois et al. Reference Brisbois, Girling and Findlay2018). They provide opportunities to understand national priorities concerning Antarctica, to provide expertise and present relevant new research to decision-makers, to co-produce papers for submission to meetings and, potentially, to become part of the National Delegation and attend the meeting as an expert advisor. In this context, a researcher who is seeking to conduct applied research is likely to be best served by understanding what decision-makers are asking for and engaging iteratively with them to ensure that their scientific research delivers what is actually needed, not what is presumed.

Often, government representatives at ATS meetings will not have detailed scientific expertise in specific topics. Neither might they have sufficient time to keep up to date with research developments or to know which researchers might be able to provide informed advice. Consequently, they may appreciate proactive efforts by researchers to provide policy-relevant scientific information. A respectful, preferably in-person encounter with a clear message is one of the best ways to build meaningful relationships and to be heard. Once relationships are established, the provision of occasional brief notes (i.e. of one page or less) can also be useful. It should be noted that simply providing information (even briefly; e.g. as a paper abstract) is often not sufficient to communicate the necessary information effectively. The onus is generally on the researcher to provide plain-language, accessible summaries and to communicate the key points of available research effectively (i.e. ‘why is the issue important?’, ‘what is new?’, ‘why now?’, ‘what does it mean in practical terms?’, ’what is the broader context?’ and ’what are the implications of policy response options?’). Careful consideration should also be given to the effective communication of the level of uncertainty inherent in the scientific data.

Contributing to the development of SCAR inputs to the Antarctic Treaty System

Another route to engage with ATS policy bodies is via SCAR. SCATS (https://www.scar.org/policy/scats/) is the body tasked with coordinating SCAR's scientific advice to the ATS (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Constable, Frenot, López-Martínez, McIvor and Njåstad2018). For any given topic, SCATS will consult with relevant experts, collate the best available evidence and present it to decision-makers in a readily understood format, predominantly via Working Papers or Information Papers. SCAR also plays an important role in highlighting and advising on emerging scientific issues with potential future significance. SCATS is well placed to provide advice to researchers on the best methods by which to communicate their science to decision-makers (contact: [email protected]).

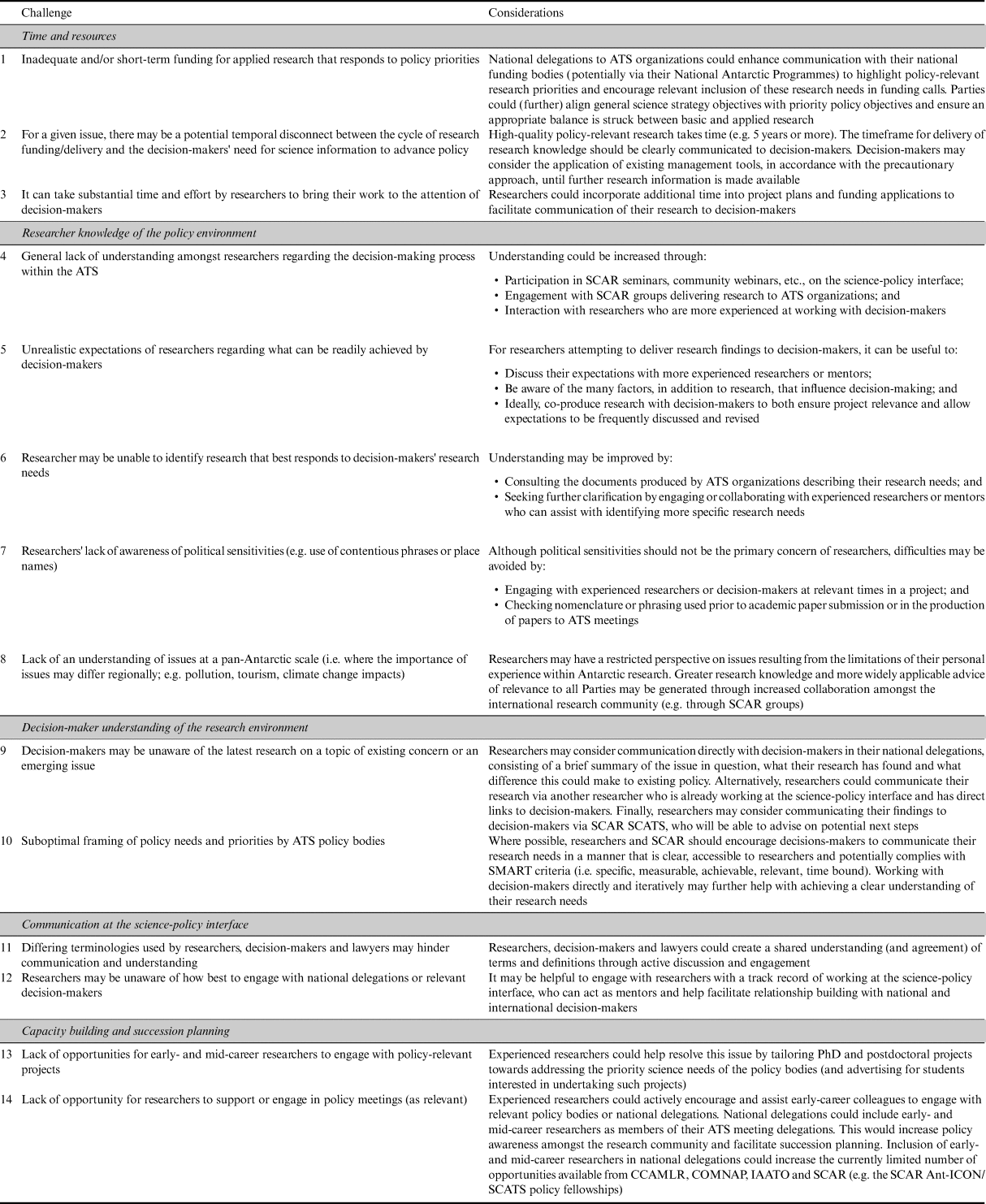

Opportunities for engagement in science-policy communication exist through other groups within SCAR that cover a range of topics of policy relevance, including the SCAR Krill Expert Group (SKEG), Plastics in Polar Environments Action Group (Plastic-AG), Input Pathways of persistent organic pollutants to AntarCTica (ImPACT) and the Scientific Research Programme (SRP) Near-term Variability and Prediction of the Antarctic Climate System (AntClimNow). The SCAR SRP ‘Integrated Science to Inform Antarctic and Southern Ocean Conservation’ (Ant-ICON; https://www.scar.org/science/ant-icon/home/) aims to facilitate and coordinate high-quality transdisciplinary research to inform the conservation and management of Antarctica, the Southern Ocean and the sub-Antarctic in the context of current and future impacts (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Santos, Caccavo, Chignell, Gardiner and Gilbert2022b). It was established in 2020 and may continue for up to 8 years from that date. The profile of researchers' work can be raised by Ant-ICON and relevant research synthesized and directed to SCATS for potential communication to decision-makers. Researchers of all careers stages can consider opportunities to join Ant-ICON and thereby potentially shape communication at the science-policy interface.