In many ways, Richard's life and work are typical of Outsider Art. Born in 1954, he lives a reclusive life, prefers the nighttime to the daytime and spends much of the night drawing and playing the guitar. The drawings themselves are a bit like highly elaborated doodles: whorls and patterns of hatching meld into mask-like faces and hieratic figures, sometimes menacing and sometimes humorous. They seem to occupy an almost agoraphobic realm (and in fact Richard finds being in the outside word quite stressful). He is reluctant to exhibit his work and is wary of the motives people might have for looking at or buying it.

I first met Richard about 30 years ago, when he was admitted to a therapeutic community and suffering from depression. At the time I was working there 4 days a week as an art therapist and group therapist. It was a most unusual situation in that, not only did I spend more time there than most people in my profession, but I was also able to set my own framework for the art therapy sessions. This entailed making them compulsory like all the other groups and also making sure that everyone, staff and patients, was expected to participate on an equal footing. This was not always easy, and in Richard's case it must have felt somewhat like Robinson Crusoe being crash-landed in a campsite.

Nevertheless he did attend; but it was perhaps an expression of his anxiety that, to begin with, he would fold the A1 paper into a much smaller rectangle on which to work, always in pastel. I shall never forget the session in which he suddenly used an entire sheet for his drawing. Then, in Richard's monthly review, the consultant unexpectedly suggested that Richard and I should have additional individual sessions. He was in fact the first of a number of patients offered this on the grounds that art therapy provided an alternative to the verbal bias of other groups: however negotiating the extent to which these sessions could be reported back on was a delicate matter.

It was only as a result of these sessions with Richard that I discovered that he made drawings at home (all patients went ‘home’ at the weekends). Until then my impression had been that Richard had such a low opinion of the doodles he often made while sitting up late talking to other patients that he usually destroyed them. I felt it important to affirm the artistic quality of his work, not only as a contribution to improving his self-image, but for its own sake, as a peculiarly intense form of creativity.

After about a year Richard left the community and became an out-patient. I then arranged to see him privately, and it was here that he first brought samples of the artwork on which he often worked all night. Whilst there are a few instances of Outsider artists communicating about their work in a therapeutic context, Aloise Corbaz is a famous example (Dubuffet and Forel, Reference Dubuffet and Porret-Forel1966), this was an exceptional privilege. I must have seen Richard in this way for about a year, and once or twice I also arranged to meet him at an art exhibition. He was both impressed and encouraged by seeing a large Paul Klee show at the Tate, London.

Towards the end of my therapeutic work with him, I mentioned that there were one or two Outsider Art collectors who might be interested in his work, notably Monika Kinley, whose collection is now housed at the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester. Although he did not respond at the time, I discovered later that he had contacted her, and she had acquired several of his drawings. Richards work was included in several exhibitions including ‘Inner Worlds Outside’ at the Whitechapel Gallery, London (Andrada et al., Reference Andrada, Martin and Spira2006) and ‘Inside Out’ at the Castlefield Gallery, Manchester (Maclagan, Reference Maclagan2016), where he was called an ‘Outsider’ artist, a label he was almost as unhappy with as that of ‘patient’ (Maclagan, Reference Maclagan2009).

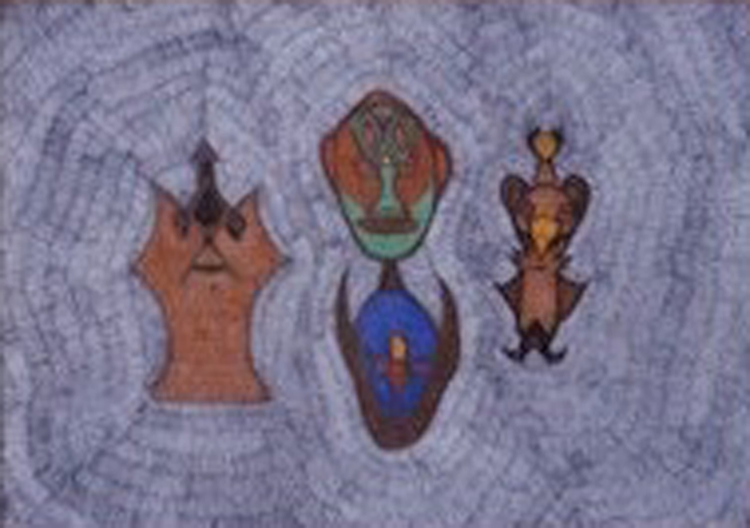

Richard's drawing has always been closely associated with playing the guitar: both are intensely private improvisations, meandering meditations that somehow build up and confirm a sense of his own individual being. More often than not, creatures or characters emerge, sometimes with the symmetry of tribal totem poles, and often enmeshed in the network of lines that gave rise to them. Although some of these figures are dark and menacing, many also have a quirky humour to them. There is often a surrounding ‘field’, protecting and containing, or perhaps establishing a kind of barely visible communication between them. As with many doodles, there is a sense of trespass in looking at them, as if they belong to a private and secret world that can only just be shared.

Fig. 1. Richard Nie, 1985, approx A2.

Fig. 2. Richard Nie, n.d., approx A2.

If Richard's work might be called ‘doodling’, it is a more sustained and intense version that has a powerful internal coherence to it, I call it a’ meta-doodle’ (Maclagan, Reference Maclagan2001). It exerts a subtle fascination that draws the viewer into something like a world created out of darkness and solitude, often peopled with brooding mask-like faces. This is a compacted underworld, reminiscent of Kafka's ‘My prison cell, my fortress’ (Kafka, Reference Kafka1988). Like signals from some inaccessible galaxy, his drawings have travelled an unfathomable distance to get to us.

About the author

David Maclagan is a retired art therapist and lecturer at the University of Sheffield. He is also an artist and writer who has published widely on the psychology of imagination, aesthetics and the image: his books include ‘Outsider Art: from the Margins to the Marketplace’ (Reaktion, 2009) and ‘Line Let Loose: scribbling, doodling and automatic drawing’ (Reaktion, 2014).

Carole Tansella, Section Editor