It is estimated that up to 30% of the general population have experienced childhood maltreatment (Hussey et al., Reference Hussey, Chang and Kotch2006). Physical, sexual and emotional or psychological abuse and neglect are among the most common types of maltreatment encountered by children and young people (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Turner, Ormond and Hamby2013). Experiences of childhood abuse and/or neglect precede the occurrence of psychiatric disorders in adult life, whereas 2.2% of incidents of childhood maltreatment result in fatalities (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). The economic burden of childhood maltreatment in terms of health care and medical costs, losses in productivity, welfare and special education costs are estimated around $124 billion in the USA alone (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Brown, Florence and Mercy2012).

Over 800 000 people across the world die by suicide every year. Understanding, therefore, the major factors which underpin suicidality such as suicide attempts, thoughts and behaviors has been established as a global health and policy priority [World Health Organization (WHO), 2014]. Empirical research has shown strong links between several types of childhood maltreatment and adult suicidality among individuals in the community and those diagnosed with psychiatric disorders (Gal et al., Reference Gal, Levav and Gross2012; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kang, Kim, Kim, Yoon, Jung, Lee, Yim and Jun2013). Consistent with the empirical findings, contemporary theories of suicidality have emphasized the role of childhood maltreatment, such as sexual and physical abuse, in the development of suicidality. For example, the interpersonal theory of suicide suggests that severe types of childhood maltreatment, such as sexual and/or physical abuse, produce a state of habituation to pain and reduction of fear for death which gradually builds the person's capability for suicide. Similarly, the Cry of pain model, and its antecessor, the Schematic Appraisals Model for Suicide (SAMS) suggest that childhood adversities give rise to increasingly worsening perceptions of defeat and entrapment which lead to suicidality as a means of escape (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Gooding and Tarrier2008; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Barnhofer, Crane and Beck2005).

To date, two meta-analyses have confirmed the positive relationship between distinct types of childhood maltreatment and suicidality (Liu, et al., Reference Liu, Fang, Gong, Cui, Meng, Xiao, He, Shen and Luo2017; Zatti, et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, da Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017). These meta-analyses, however, combined studies which were based on mixed samples of participants such as adolescents and adults, community and clinical samples. On the other hand, methodological restrictions have been applied regarding the definition of childhood maltreatment (e.g. use of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire exclusively; CTQ; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fang, Gong, Cui, Meng, Xiao, He, Shen and Luo2017), the study design (e.g. prospective studies only) and the date of publication (conducted within the last decade; Zatti et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, da Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017), leading to the exclusion of several relevant studies. Moreover, little is known regarding the impact of demographic and clinical factors on the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality. Although these studies are important, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis would be particularly valuable for drawing important evidence-based conclusions and guiding future research priorities. We performed a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality. We had two core objectives:

• To systematically quantify the association between different types of childhood maltreatment and suicidality, including suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

• To examine demographic, clinical and methodological factors that may influence the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality in adults.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis is aligned with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) and the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE; Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000).

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to meet five criteria to be included in the review: (a) based on participants aged 18 years or older, who were exposed to childhood maltreatment such as abuse or neglect, (b) reported data on suicidality including suicide attempts, suicidal ideation or suicide deaths in adults exposed to childhood maltreatment (e.g. before the age of 18 years old) or reported a quantitative outcome of the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality in adults; (c) focused on individuals from the community or individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, (d) employed an observational quantitative research design and (e) written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. We excluded studies which examined other types of maltreatment than abuse or neglect (e.g. bullying, parental divorce, loss/death of a loved one, separation from parents, witnessing violence), were based on veterans (this population differs from non-veterans on such variables as being pre-selected based on specific mental and physical criteria, having an increased likelihood of experiencing adversities in adulthood by encountering or witnessing stressful events and aging over 60 years old; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014), and did not provide amendable data for meta-analyses.

Search strategy and data sources

We searched five electronic bibliographic databases including Medline, PsychInfo, Embase, Web of Science and CINAHL. We also checked the reference lists of the identified studies to locate eligible studies and contacted the authors, whenever needed. The searches were conducted on 25 January 2018. Our search strategy included both text words and MeSH terms (Medical Subjective Headings) and combined two key blocks of key-terms: suicide (suicid* OR self*harm) and child/sexual/physical/emotional abuse or neglect or maltreatment or adversities (child*, sex*, phys*, emoti* abuse, negl*, maltreat*, advers*).

Study selection

Two reviewers independently scrutinized the titles and the abstracts of the research papers identified. Then, the full texts of the potentially eligible studies were further evaluated independently by the two reviewers. Inter-rater reliability was high for title/abstract and full-text screening (κ = 0.95 and 0.97, respectively). Disagreements were resolved by discussions.

Data extraction

First an electronic data extraction sheet was devised and piloted in six randomly selected studies. We extracted descriptive data on participant characteristics (e.g. age, gender), study characteristics (e.g. country, design, method of recruitment), screening tools for childhood maltreatment, type of maltreatment (e.g. sexual, physical and emotional/psychological abuse, and emotional or physical neglect), screening tools for suicidality and mode of suicidality (e.g. suicide attempts or suicidal ideation). Quantitative data for meta-analysis examining the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality were also extracted. Two independent reviewers completed the data extraction. Inter-rater agreement was found to be as high as κ = 0.93 on 875 points checked.

Critical appraisal assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was critically appraised by using six criteria which were adapted by the CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care (CRD, 2009) and the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci2004). These were: (i) research design (cross-sectional = 0, prospective/experimental = 1), (ii) baseline response rate (>70% or no reported = 0, <70% = 1), (iii) follow-up response rate (>70% or no reported = 0, <70% = 1), (iv) screening tools for childhood adversities (not reported/other = 0, structured/semi-structured clinical interview/self-report scale = 1), (v) screening tools for suicidality (not reported/other = 0, structured/semi-structured clinical interview/self-report scale = 1) and (vi) control for confounding/other factors in the analysis (no controlled/no reported = 0, controlled = 1). Studies which met at least four of these six criteria were considered to be of moderate to high quality, whereas studies which met fewer than four criteria were considered to be of low quality. Using this classification, a binary critical appraisal item was created across studies (1 = low quality appraisal score; 2 = moderate to high quality appraisal score) which was entered as moderator in the meta-regression analyses.

Data analyses

Our primary outcome was the association between suicide attempts and different types of childhood maltreatment. All studies reported suicide attempts as dichotomous outcomes (number/proportions of participants with or without experiences of childhood maltreatment who engaged in suicide behavior in adulthood). Most studies (except for four studies) also reported suicidal ideation as dichotomous outcomes. Odds ratios (ORs) were, thus, selected as the preferred effect size across all analyses. Data from the four studies which reported secondary outcomes in different formats (e.g. mean score of suicidal ideation in participants with and without history of childhood maltreatment) were converted to ORs by utilizing a widely used formula (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2005). Most of the included studies contributed more than one relevant effect size for our analyses (e.g. the reported associations between several types of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts). For this reason, we pooled the different types of childhood maltreatment separately to avoid double counting of studies in the same analysis.

We pooled all data in Stata 15 using the metan command and conducted univariable and multivariable meta-regressions to test the influence of study-level moderators on the associations between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts using the metareg command (Harbord and Higgins, Reference Harbord and Higgins2008). Six moderators were tested including mean age, percentage of men in the sample, population (community v. clinical sample), assessment method of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation (self-report questionnaire v. clinician or researcher administered interview), assessment method of childhood maltreatment (self-report questionnaire v. clinician or researcher administered interview) and critical appraisal score (low v. high score). We also examined whether the type of mental health condition (common v. severe) affected the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts within the clinical sample. According to published guidance, each moderator value was based on a minimum of eight studies (Thompson and Higgins, Reference Thompson and Higgins2002). Covariates meeting our significance criterion (p < 0.20) were entered into a multivariable meta-regression model. The p < 0.20 threshold was conservative, to avoid prematurely discounting potentially important explanatory variables.

Analyses were primarily conducted using a random effects model because we anticipated substantial heterogeneity, which was assessed with the I 2 statistic (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003). For comparisons that included fewer than five effect sizes, we used a fixed effects model in cases of moderate to low heterogeneity (⩽50%). Conventionally, values of 25, 50 and 75% indicate low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was examined by inspecting the funnel plots. Provided that the analyses were based on at least 9 studies, we applied formal tests including the Egger's tests (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997). In case of possible publication bias, we used the Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method, which corrects the estimated effect size by yielding an estimate of the number of the missing studies (Duval and Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000).

Results

A total of 5370 articles were retrieved. Of these, 388 were duplicates and 4698 were excluded because they (a) did not focus on suicidality, (b) focused on any other childhood maltreatment sub-types other than abuse or neglect (e.g. bullying, parental divorce, loss/death of a loved one, separation from parents, witnessing violence) and (c) were non-empirical studies, leaving 284 articles eligible for full-text screening. An additional 216 studies were excluded as they either did not report data relevant to the link between childhood abuse and suicidality or were based on adolescents or veterans. A total of 68 independent studies were included in the review (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram for the entire review.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies

The characteristics of the 68 studies that were included in the review are detailed in Table 1. The vast majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (k = 29; 42.65%), followed by Canada (k = 7; 10.29%), Italy (k = 3; 4.41%), Turkey (k = 3; 4.41%), Germany (k = 3; 4.41%) and Brazil (k = 3; 4.41%). Fewer studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (k = 2; 2.94%), Australia (k = 2; 2.94%), New Zealand (k = 2; 2.94%), France (k = 2; 2.94%), Netherlands (k = 2; 2.94%), Poland (k = 2; 2.94%) and Korea (k = 2; 2.94%), whereas a single study (1.47%) was conducted in Argentina, Spain, Norway, Israel, Japan and South Africa. Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Chiu, Hwang, Kessler, Sampson, Alonso, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, He, Kovess-Masfety, Levinson, Matschinger, Mneimneh, Nakamura, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Scott, Tomov, Viana, Williams and Nock2010) presented data that have been collected from 21 countries.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the studies included in the review

M, mean; s.d., standard deviation; n/r, not reported; QA, quality appraisal of the methodology of the included studies.

The age of the participants ranged between 18 and 93 years old (M age = 40.26, s.d. = 8.69; 42.34% men). In total, 33 studies (n = 225.462) were based on community samples and 35 on clinical samples (n = 36.198). Twenty-one of the studies that utilized psychiatric patients focused on common types of mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 14 on severe types of mental health conditions, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Childhood maltreatment was assessed using two main methods: (i) 44 studies used self-report questionnaires and (ii) 23 studies used clinical interviews and other objective methods (e.g. five studies retrieved relevant information by patient records; only one study by Fudalej et al. (Reference Fudalej, Ilgen, Kołodziejczyk, Podgórska, Serafin, Barry, Wojnar, Blow and Bohnert2015) did not specify the tools utilized). The most common self-report measure was the CTQ. Similarly, suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts were assessed either using self-report questionnaires (k = 33 studies) or structured/semi-structured clinical interviews or other objective methods (k = 35, of which five studies retrieved relevant information by patient records).

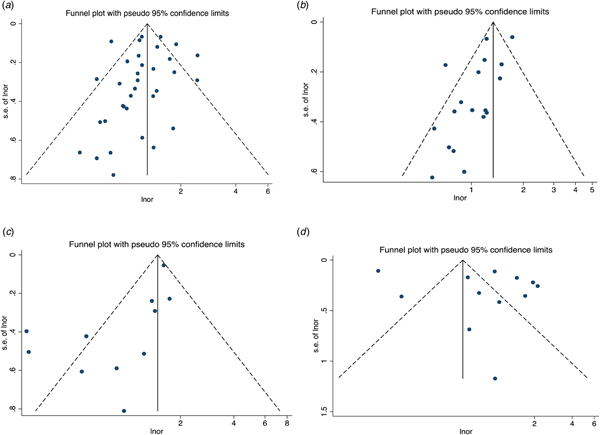

Fig. 2. Funnel plots for effect sizes. Childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts: (a) sexual abuse, (b) physical abuse, (c) emotional abuse and (d) any child abuse.

Table 1 also presents the overall scores from the critical appraisal assessment of the studies. Almost half of the studies (k = 37) scored moderate to high in the critical appraisal assessment (met four or more criteria) whereas the remaining scored low (met fewer than four criteria).

Main meta-analyses: associations between types of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in adults

The pooled effects of the main analyses indicate that all types of childhood maltreatment (except for physical neglect which is only based on four studies) were associated with significantly increased odds for suicide attempts in adults (Table 2). Sexual abuse was associated with a three-fold increased risk for suicide attempts [k = 36, OR 3.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.76–3.64, I 2 = 68.1%] whereas physical and emotional abuse were associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk for suicide attempts (k = 30, OR 2.52, 95% CI 2.09–3.04, I 2 = 74.3% and k = 12, OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.64–3.77, I 2 = 93.2%, respectively). Emotional neglect was associated with 2.3-fold increased risk for suicide attempts whereas physical neglect was not significantly associated with an increased risk for suicide attempts (k = 6, OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.79–2.94, I 2 = 19.2% and k = 4, OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.87–2.62, I 2 = 62.3%, respectively). However, the two categories focused on neglect were based on a small number of studies which have distinguished emotional/physical abuse from emotional/physical neglect. Moreover, a considerable number of studies examined the association between a combined category of childhood abuse (without providing data on each separate form of abuse) and suicide attempts. We named this combined category as any child abuse and analyzed it separately because it contains unspecified features from more than one of the other categories. Any child abuse was associated with a two-fold increased risk for suicide attempts (k = 16, OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.67–2.60, I 2 = 91.3%). Finally, complex abuse (repetitive incidents) in childhood showed the strongest association (increased the risk five times) with suicide attempts among adults (k = 7, OR 5.18, 95% CI 2.52–10.63, I 2 = 90.9%). As indicated by the value of I 2 statistic, heterogeneity was medium to high across all the main analyses.

Table 2. Results of meta-analyses of the association between child maltreatment and suicidality (k = 68)

k, number of independent effect sizes; OR, pooled odds ratio, N, number of participants.

a One outlier was dropped from the analyses.

Secondary meta-analyses: associations between types of childhood maltreatment and suicidal ideation in adults

All types of childhood maltreatment were associated with significantly increased odds for suicidal ideation in adults. Sexual abuse and emotional abuse were associated with a two-fold increased risk for suicidal ideation (k = 12, OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.77–2.62, I 2 = 53.8% and k = 5, OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.51–2.94, I 2 = 54.4%, respectively) whereas physical and any child abuse were associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk for suicidal ideation (k = 11, OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.85–3.18, I 2 = 64.6% and k = 7, OR 2.66, 95% CI 1.93–3.68, I 2 = 81.4%, respectively). Emotional and physical neglect were associated with 1.5-fold increased risk for suicidal ideation (k = 4, OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.02–1.93, I 2 = 80.3% and k = 4, OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.06–1.95, I 2 = 70.3%, respectively). As indicated by the value of I 2 statistic, heterogeneity ranged from medium to high across all analyses.

Small study bias

We assessed for publication bias across analyses which included at least nine studies (see also funnel plots; Fig. 2). In none of the main (sexual abuse-suicide attempts, p = 0.28, physical abuse-suicide attempts p = 0.11, any child abuse-suicide attempts p = 0.06) and secondary analyses (sexual abuse-suicidal ideation, p = 0.08, physical abuse-suicidal ideation, p = 0.07), the Egger's test for publication bias was significant except for the association between emotional abuse and suicide attempts (bias = 0.57, 95% CI 0.14–1.00, p = 0.02). For this comparison we run the Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method which reduced slightly the effect size.

Meta-regressions exploring the variance in the association between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts

The results of the univariable and multivariable analyses are shown in Table 3. The numbers of pooled studies only allowed meta-regressions to examine factors which affect the associations between sexual abuse, physical abuse and suicide attempts.

Table 3. Meta-regression analyses

CM, childhood maltreatment.

a These analyses were based on the clinical sample only (k = 17 and k = 13 for the associations between sexual abuse and suicide attempts, and between physical abuse and suicide attempts, respectively).

Sexual abuse and suicide attempts (k = 36)

Studies which were based on older participants (b = 0.02, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.06, p = 0.09), community samples (OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.77–3.64, p = 0.19), and assessed suicide attempts using clinical interviews (OR 2.12, 95% CI 0.99–4.57, p = 0.05) tended to report a larger association between sexual abuse and suicide attempts in univariable analyses and were eligible for inclusion in multivariable analysis. The overall multivariable model was statistically significant χ2(3) = 3.11, p = 0.04 and reduced the I 2 statistic from 68.1% to 41.02%. Population was the only predictor which approached significance in the multivariable analyses suggesting that the association of sexual abuse and suicide attempts may be stronger in community samples compared with clinical samples (b = 0.69, 95% CI −0.02 to 1.42, p = 0.06).

Physical abuse and suicide attempts (k = 25)

Studies based on older participants (b = 0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.09, p = 0.02) and a higher percentage of women (b = −0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.01, p = 0.10) tended to report a larger (although non-significant) association between physical abuse and suicide attempts in univariable analyses and were eligible for inclusion in multivariable analysis. The overall multivariable model was statistically significant χ2(3) = 3.99, p = 0.02 and reduced the I 2 statistic from 74.3% to 51.87%. Age was significant predictor and gender approached significance in the multivariable analyses suggesting that the association between physical abuse and suicide attempts is stronger in studies based on older participants and women (b = 0.05, 95% CI 0.02–0.09, p = 0.03 and b = −0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.00, p = 0.07).

Last, we examined whether common types of mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression and PTSD, or more severe conditions, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, affected the association between childhood maltreatment and suicidality within clinical populations. However, our analyses did not support such a distinction (see Table 3).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The most comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to date demonstrated that suicidality is a major concern in adults who have experienced core types of childhood maltreatment (e.g. abuse, neglect). A two- to three-fold increased risk for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation was identified in adults who experienced sexual, physical or emotional abuse as children compared with adults who have not experienced maltreatment during childhood. Adults exposed to sexual abuse and complex abuse in childhood were particularly vulnerable to suicidality. The relationship between major types of childhood maltreatment such as sexual and physical abuse and suicide attempts was not moderated by the characteristics of participants across studies (e.g. gender, the presence and severity of psychiatric diagnoses) and methodological variations (measures of childhood maltreatment or suicidality, critical appraisal scores). The only notable exception was that age moderated the association between physical abuse and suicide attempts, in that older participants were at higher risk for suicide attempts. The association between sexual abuse and suicide attempts also tended to be higher in community samples but this moderating effect was not significant. Our findings are especially supportive of early interventions to reduce suicide risk in people exposed to childhood maltreatment (as suicide risk could become more severe as these people age) and regular assessments for experiences of childhood maltreatment among people who self-harm or report thoughts of suicide followed by appropriate therapeutic management. Moreover, these findings encourage community interventions particularly for non-clinical populations who experience a significant but often untreated risk for suicide because these people are less likely to be in regular contact with mental health support services. In the latest case, community programs might have the most realistic potential to achieve intervention reach and be implementable at scale.

Key research considerations and theoretical implications

The findings of the main analyses are generally consistent with the findings of less extensive systematic reviews in that childhood maltreatment is associated with a greater risk for suicide attempts (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fang, Gong, Cui, Meng, Xiao, He, Shen and Luo2017; Zatti et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, da Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017). We have advanced the existing literature with the use of a larger pool of studies which allowed us to further examine the impact of core moderators on the relationship between major types of childhood abuse and suicide attempts. Our methodology also enabled us to confirm a significant relationship between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation. Previous reviews reported non-significant pooled effect sizes of the association between childhood abuse and suicidal ideation but they were based on a considerably smaller number of studies compared with our analyses. In terms of suicide deaths, there is a paucity of evidence. We only identified one large retrospective study that presented relevant data on suicide deaths among 12 million participants (Cutajar et al., Reference Cutajar, Mullen, Ogloff, Thomas, Wells and Spataro2010); between 1964 and 1995 individuals who had been sexually abused had an 18-fold greater risk for dying by suicide (OR 18.14, 95% CI 9.05–36.36).

Older age was the only significant moderator of the association between physical abuse and suicide attempts. We speculate that as people who have been maltreated in childhood age, they are less capable of buffering the impact of life stresses or negative life events and therefore they gradually become less resilient and more prone to suicidality. More research is needed to investigate this hypothesis. Moreover, our finding that the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts does not differ across people with severe mental health conditions, common mental health conditions and people from the community with no known mental health problems is of major importance because it suggests that the impact of childhood abuse on suicide risk is direct and trans-diagnostic. The finding that gender did not moderate the association between childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts seems to be consistent with the extant literature which suggests that males and females do not differ in their exposure to the overall number of adversities in childhood but rather in their exposure to specific types of childhood maltreatment (Freedman et al., Reference Freedman, Gluck, Tuval-Mashiach, Brandes, Peri and Shalev2002). For example, several studies have demonstrated that males experience more frequently physical abuse, whereas females encounter more frequently experiences of sexual abuse (e.g. Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Sonega, Bromet, Hughes and Nelson1995).

In terms of theoretical implications, the findings of this review could suggest that all types of childhood maltreatment operate on suicidality via a single mechanism. Gibson and Leitenberg (Reference Gibson and Leitenberg2001) proposed that powerlessness mediates the relationship between sexual abuse and disengagement, defined as any form of cognitive or behavioral avoidance. Considering the commonalities between feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness, as well as defeat and entrapment, such appraisals could potentially mediate or moderate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidality (e.g. O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, O'Connor, Platt and Gordon2011). However, there are no empirical findings to confirm this hypothesis. Furthermore, childhood abuse has also been found to be strongly associated with a diagnosis of PTSD which is one of the most well-known risk factors for suicidality (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Hughes, Blazer and George1991; Panagioti et al., Reference Panagioti, Gooding and Tarrier2009, Reference Panagioti, Gooding and Tarrier2012; Tarrier and Gregg, Reference Tarrier and Gregg2004; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Gooding, Wood and Tarrier2011). Empirical research examining the mechanisms of suicidality in PTSD has supported the validity of contemporary models of suicidality, including the SAMS, which postulates that feelings of hopelessness (which often interact with recent negative experiences) lead to defeat and entrapment and subsequently to suicidality in PTSD patients (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Gooding and Tarrier2008). A recent meta-analysis also highlighted the trans-diagnostic sequel of defeat and entrapment which is present in several conditions including depression, anxiety, PTSD and suicidality (Siddaway et al., Reference Siddaway, Taylor, Wood and Schulz2015). Thus, the mediating/moderating effects of such cognitive appraisals (including disengagement) remain to be tested in models aimed at identifying the underlying mechanisms leading to suicide for those who experienced childhood maltreatment.

Strengths and limitations

This large systematic review and meta-analysis has several strengths. It has been conducted in accordance with published guidance (PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines) which entails the involvement of two independent researchers throughout the screening, data extraction and data synthesis, the critical appraisal of the methodological quality of the studies and the performance of inter-rater reliability tests and advanced statistical analyses (e.g. multivariable meta-regressions).

However, there are a number of limitations which warrant discussion. First, significant heterogeneity was detected across most of the analyses. We dealt with heterogeneity by applying random effect models and conducted multivariable meta-regression analyses to further explore key sources of heterogeneity among the studies. Second, the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis have been derived by English language peer-reviewed papers. It is reassuring that formal tests indicated no evidence of publication bias in our core analyses. One exception was the analysis which examined the association between emotional abuse and suicide attempts in which publication bias was a potential threat. Although the pooled effect has been adjusted using the trim-and-fill approach, the results of this analysis should be interpreted with caution. Third, our core analyses included a relatively large number of studies which also allowed us to perform advanced analyses (e.g. meta-regressions). However, this option was not always appropriate because some analyses were based on a small number of studies (e.g. analyses of the associations between suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and emotional/physical neglect). Fourth, the majority of the studies in our analyses were cross-sectional. Although the occurrence of suicide attempts or suicidal ideation cannot temporally precede childhood abuse, large longitudinal studies are recommended to examine the causal mechanisms of suicidality among survivors of childhood abuse over time. Last, in this review, we have only considered core and severe types of childhood maltreatment. There is evidence that other types of childhood maltreatment such as experiences of bullying, separation from parents or dysfunctional attachment styles are linked with suicidality particularly in people with severe mental health conditions such as psychoses, bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Another systematic review to examine the association between suicidality and experiences of bullying, separation and attachment styles is fruitful avenue for future research.

Conclusion

This is the most comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis to corroborate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adult suicidality. Our main findings demonstrated that all types of childhood abuse are associated with increased risk for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in adults independent of demographic, clinical and methodological variations across the studies. Beyond this, there is a major gap in the literature regarding the mechanisms by which experiences of childhood maltreatment exert their detrimental, long-lasting impact on suicide risk. A better understanding of the causal mechanisms of suicidality in people exposed to childhood maltreatment has the potential to guide the development of more efficient interventions which will specifically target these causal mechanisms.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003823.

Author ORCIDs

Ioannis Angelakis, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1493-7043; Maria Panagioti, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7153-5745.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Matilda Angelaki for her useful comments on the manuscript.

Financial support

No financial support has been received for this piece of work.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.