There has long been a tension in the United States over the right to freely express opinions and societal norms regarding what type of speech is acceptable in the public domain, especially concerning speech targeted at marginalized groups in society, such as racial and ethnic minorities. While laws related to hate speech define the boundary between expressing opinion and inciting violence, the use of inflammatory speech that does not reach the threshold of legal prohibition is constrained only by strong social norms of equality and tolerance (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). These norms proscribe the explicit expression of racial prejudice and open engagement in discriminatory behavior. At the mass level, scholarship finds that awareness of these norms, along with concerns about behaving in a socially desirable manner, have played an important role in suppressing the expression of overt prejudice in the post-Civil Rights era (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Schuman et al. Reference Schuman1997). At the elite level, we have seen these dynamics play out on the campaign trail, as elite communication has substantially gravitated away from the use of explicit racial appeals (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1992; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). While norms are generally entrenched, the preservation of a ‘norm environment’ requires continued reinforcement of the norm, especially by authoritative societal actors like political elites.

What happens when political elites challenge a prevailing norm environment? For example, does the use of racially inflammatory rhetoric open the floodgates for prejudice among the mass public? That is, does it embolden members of the public to express deeply held prejudices? These questions have become increasingly salient, particularly in light of Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, which was punctuated by a consistent series of inflammatory statements targeting racial and ethnic minorities. From the outset, Trump bucked conventional wisdom – among both practitioners and the academy – by using explicitly racial language, especially with regard to Mexican immigrants. During his presidential announcement speech, he made the now infamous remarks about Mexican immigrants: ‘When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best … They're sending people that have lots of problems, and they're bringing those problems with them. They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists’.Footnote 1 This is but one example of his explicitly racial rhetoric.

There is an accumulating body of anecdotal evidence that Trump's racial rhetoric on the campaign trail emboldened members of the American public to more openly express and act on their existing prejudices – a phenomenon some have labeled the ‘Trump effect’ (Costello Reference Costello2016). Countless incidents of violence took place against protestors at Trump rallies,Footnote 2 often inspired by the candidate himself,Footnote 3 and many of these protestors were members of marginalized groups.Footnote 4 Journalists have suggested that racist language has increased in comments onlineFootnote 5 and in schools.Footnote 6 Moreover, the Southern Poverty Law Center tracked a drastic increase in bias-related incidents in the month after Trump's electoral victory over Hillary Clinton – 1,094 overall, with anti-immigrant incidents as the most common type (315).Footnote 7 Worthy of particular note is the spike in anti-Muslim hate crimes during the 2016 presidential election,Footnote 8 especially in areas with heavy Twitter usage during Trump's campaign (Muller and Schwartz Reference Müller and Schwartz2018a). To many observers, these incidents represent hateful acts emboldened by Trump's rhetoric on the campaign trail and elevation to the nation's highest political office. However, these claims are still largely conjecture, as there is limited scholarly evidence that exposure to Trump's racially inflammatory speech caused Americans to express their own prejudices or engage in discriminatory behavior. Furthermore, it is unclear whether this type of speech alters citizens' perceptions of the norm environment, or whether one's response depends on how other political elites react.

In this article, we argue that exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech makes it more likely that individuals will bring their prejudice to bear on judgments of socially acceptable behavior against minorities and on the likelihood of engaging in discriminatory behavior. We conceptualize this process as an ‘emboldening effect’. Furthermore, we argue that this emboldening effect will be conditional on signals citizens receive from the norm environment via other authoritative societal actors. We contend that exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech will have the strongest emboldening effect when citizens receive signals that other elites tolerate such speech. While a long literature in political science has examined the effect of racial rhetoric on policy preferences and candidate evaluations, we explore a novel dimension related to the norms of interpersonal conduct. We treat politics as an independent variable, and examine how it spills over into everyday interactions among individuals.

To test our expectations, we investigate the impact of Donald Trump's rhetoric against Latino immigrants during the 2016 presidential election. We conducted an online survey experiment in two waves from late March to early April 2016, in the midst of the primary election period. We find that exposure to racially inflammatory statements by Trump caused those with high levels of prejudice to be more likely to perceive engagement in prejudiced behavior as socially acceptable. Importantly, we find that the magnitude of this effect is enhanced when exposure to inflammatory speech by Trump is coupled with information that other political elites tacitly condone his speech. Interestingly, we also find some evidence that referencing Trump without mentioning immigration or his inflammatory remarks was sufficient to embolden the expression of prejudice. We believe this is likely because our experiment was conducted at a time when Trump's inflammatory comments about Latino immigrants (made in speeches delivered in 2015) had already been a focal point of public discourse about the upcoming election for several months.Footnote 9 As prior research documents, the linking of concepts in public discourse can lead individuals to couple the concepts in their mind, for example in the case of ‘welfare’ and ‘African American’ (Gilens Reference Gilens1999) or ‘immigrant’ and ‘Latino’ (Pérez Reference Pérez2016). We interpret this effect as suggesting that Trump has become coupled with ‘anti-immigrant’ in the minds of Americans. Last, we uncover a complementary pattern of effects in relation to prejudiced behavior toward a Latino individual, suggesting that our findings extend to personal engagement in harm-intending behavior.

While our focus is on the US case, these questions extend well beyond that context. The last decade has seen the rise of populist leaders and parties, in particular on the right, in many European countries, including, Nigel Farage's UK Independence (UKIP) Party in the UK, Geert Wilders' Freedom Party in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen's Front National, the Austrian Freedom Party, and the Danish People's Party (Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2019). Concerns about immigration and hostility toward immigrants have been shown to be important drivers of support for these leaders and parties (for example, Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Ford and Goodwin Reference Ford and Goodwin2017; Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2015). Concerns about immigration were also a key motivation among those supporting Brexit in the UK (for example, Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2017; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016). While these studies have not focused specifically on elite rhetoric, they often note the anti-immigration rhetoric of these leaders and parties. Some have found suggestive evidence that elite cues were important in the Brexit vote (Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2017), and that public reactions to such parties vary by social norms against prejudice (Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Ivarsflaten, Blinder and Ford Reference Ivarsflaten, Blinder and Ford2010).Footnote 10 As such, the findings we report in this article provide an important point of evidence that confers feasibility on the assertion that anti-immigrant rhetoric by European elites may embolden anti-immigrant political action among citizens throughout Europe.

Norms of Equality and Tolerance in the Post-Civil Rights Era

In this section, we briefly review the literature on norms, paying particular attention to how they work to limit the expression of prejudice. We adopt the definition of norms used by Mendelberg (Reference Mendelberg2001, 17): ‘an informal standard of social behavior accepted by most members of the culture and that guides and constrains behavior’. Norms are therefore not formal and legally binding; they primarily gain their strength due to an individual's sense of ‘obligation’ to follow them in order to avoid social censure (DeRidder and Tripathi Reference DeRidder and Tripathi1992), or in a more positive sense, if they seek to gain social approval (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001).

Norms can be connected to any range of domains, but we focus on the norm of racial equality and how it has served to limit the expression of prejudice. While racial inequality was the norm into the early twentieth century, the norm began to shift to one of racial equality in the 1930s and became firmly entrenched in the post-Civil Rights era (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). With this shift, individuals who harbor negative attitudes toward blacks, but who nonetheless comply with the norm of racial equality, would be less inclined to publicly admit to, and presumably act on, their prejudice. For example, support for ‘old-fashioned’ racism, as measured by beliefs in black biological inferiority or support for segregation, began to all but disappear on surveys, though some whites still expressed a desire for social distance between races (Tesler Reference Tesler2013).

These norms have also affected the types of racial appeals used and deemed acceptable by political elites. As Mendelberg (Reference Mendelberg2001) documents, before the norm of racial equality was firmly rooted, candidates would use explicit racial appeals (that is, play the ‘race card’) in campaign communications to appeal to prejudiced voters. However, once the norms of racial tolerance and equality became entrenched, such explicit appeals became ineffective, as individuals would recognize the message as violating these norms (Stryker et al. Reference Stryker2016). In short, these norms have had a powerful influence over public opinion and the conduct of politics. Such norms are also present in many Western European countries (Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflate Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Ivarsflaten, Blinder and Ford Reference Ivarsflaten, Blinder and Ford2010). For example, Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten (Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013) argue that some radical right parties have not reached their electoral potential in part because those with anti-immigrant attitudes who are motivated to control prejudice are less inclined to support traditional parties on the right that have fascist legacies.Footnote 11

Despite the dampening effects of norms, a large corpus of research demonstrates that these racial norms are best understood as widely held but not deeply internalized. While whites came to support racial equality in principle across a variety of domains, they were not as supportive of civil rights policies that would address concrete inequalities (McClosky and Zaller Reference McClosky and Zaller1984; Schuman et al. Reference Schuman1997). Whites who were less supportive of such policies became increasingly unlikely to express these attitudes on surveys over time, given social desirability pressures (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2002). However, when unobtrusive techniques such as list experiments are used, individuals express more negative racial attitudes, particularly in the South (Kuklinski, Cobb and Gilens Reference Kuklinski, Cobb and Gilens1997). And, even with these norms in place, a nontrivial percentage of Americans have remained comfortable expressing overt racism (Huddy and Feldman Reference Huddy and Feldman2009). Given that these norms are not deeply internalized, scholars found that negative racial attitudes can still be activated, just not with explicit racial cues. For example, negative racial attitudes captured via stereotype measures dampen support for policies such as affirmative action and welfare, especially when linked to racially coded language or symbols, or in more racially diverse contexts (for example, Gilens Reference Gilens1996a, Gilens Reference Gilens1996b; Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley2005; also see Weber et al. Reference Weber2014, who find these effects among low self-monitors). On the campaign trail, campaigns and policy makers began to implicitly use race to activate racial resentment and increase support for more conservative candidates (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Valentino, Hutchings and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002; White Reference White2007; cf. Huber and Lapinski Reference Huber and Lapinski2006). The US political landscape experienced a massive realignment following the Civil Rights era, whereby racially prejudiced citizens, particularly those residing in the American South, have gradually moved toward the Republican Party (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1990; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears2005) and Republican candidates would often use implicit racial appeals to tap into voters' deeply held prejudices. The primary takeaway from this work is that equality norms did not lead to the disappearance of prejudice; rather, it simply went ‘underground’ and could be activated under certain conditions using particular types of appeals.Footnote 12

Taken as a whole, the existing literature suggests that the prevailing norm environment is sustained by the internalization of norms among elites and members of the public on the one hand, and compliance with norms among these individuals as well as those who hold negative racial attitudes on the other hand. Therefore, underlying a surface of norm compliance are undercurrents of prejudiced sentiment that create a potential basis for threat to the norm; entrepreneurial political elites can (and do) harness these undercurrents.

Elite Speech and Challenges to the Norm Environment

An entrepreneurial elite may seek to gain political advantage by appealing to those who harbor negative racial attitudes by challenging or even violating norms. These effects may be especially powerful in the case of norms that are not broadly internalized, over which there is latent conflict, like racial attitudes. We know that most citizens recognize the norm of racial egalitarianism, and that it does constrain behavior, but we also know that prejudice has taken on other forms of coded expression in this type of environment, both in the expression of public attitudes (for example, symbolic racism, racial resentment, etc.), behavior, and elites’ use of implicit racial appeals. Thus, there is an underground reservoir of persisting prejudice, and entrepreneurial elites can violate the norm environment in an attempt to ‘flank’ (Miller and Schofield Reference Miller and Schofield2003) prejudiced voters.

Recent scholarship argues that the Obama presidency created such an opening for political elites, as there have been many signs that negative racial attitudes have become increasingly salient and activated in a number of domains. During the historic 2008 election, both implicit (Pasek et al. Reference Pasek2009) and explicit (Piston Reference Piston2010) negative racial attitudes worked to dampen support for Obama. Indeed, Obama's victory led to declines in public perceptions of discrimination against blacks, particularly among those identifying with the political right (Valentino and Brader Reference Valentino and Brader2011). During the Obama presidency, old-fashioned racism levels rose (Tesler Reference Tesler2016) and Americans became more likely to bring negative racial attitudes to bear on their opinions on non-racial policies linked to the president (Tesler Reference Tesler2012). Importantly, there were signs leading up to the 2016 election of frustration among racially resentful voters, in particular with the rise of the Tea Party (Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2014). In sum, there is strong evidence that the Obama presidency intensified white citizens' racial anxieties and caused prejudice to rise to the surface, which in turn may have lessened the risk of a backlash for the use of explicit racial appeals.

To be sure, there is already some evidence that elites will not necessarily be punished for using explicit racial rhetoric. For example, Donald Trump's language on immigration is not very different from rhetoric used earlier by Representative Tom Tancredo in appearances on Fox News (Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016). Explicit appeals have been found to be effective among those who have not deeply internalized norms of racial egalitarianism, such as white southern men (Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin Reference Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin2009). Furthermore, in a series of four experiments conducted well before Trump's run for office, Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek (Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2017) show that implicit and explicit racial campaign messages now have a similar effect on candidate evaluations for the general population, a stark contrast to research from the 1990s that only found effects for explicit appeals among white southerners. These findings have been obtained even though individual support for norms of racial equality have not shifted.

This work strongly suggests that the Obama presidency created a ripe context for an entrepreneurial elite to gain political advantage by bucking norms through the use of explicit racial rhetoric in an effort to appeal to racially resentful voters. When elites violate norms, it not only resonates with the prejudiced by increasing their support for racially conservative candidates and policies (that is, we know that prejudiced voters supported Trump (Kalkan Reference Kalkan2016;Footnote 13 Vavreck Reference Vavreck2016));Footnote 14 it may also have other important downstream consequences. Given that elites have a certain degree of authority and shape public opinion and behavior (Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), this could have the effect of altering interpersonal relations in society. If individuals receive signals from prominent elites that it is acceptable to use explicitly racial rhetoric, that should make them more inclined to bring their prejudice to bear on a range of attitudes and behavior. That is, an era that was once characterized by implicit racial appeals and coded prejudice may give way to explicit appeals, and this may alter citizens' perceptions of the norm environment and what types of behaviors are publicly acceptable. We hypothesize (Hypothesis 1) that individuals exposed to such rhetoric are more likely to bring their underlying prejudice to bear on views of publicly acceptable behavior toward minorities, as well as their own behavior – a phenomenon best characterized as an ‘emboldening effect’.Footnote 15

Importantly, as the communications of individual political elites do not occur in a vacuum, the efficacy of explicit racial appeals should depend on the responses of other elite societal actors. For instance, if other political elites condemn explicit racial appeals and reinforce norms of tolerance and equality, it may inhibit this type of emboldening effect. This should especially be the case if the critique is coming from a member of the candidate's own party. For example, while Republicans might easily use partisan filters to dismiss critiques of Trump's rhetoric by Democrats (Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), they will be less able to engage in motivated reasoning when the critique is coming from members of their own party, which occurred on the campaign trail in the 2016 election (Bierman Reference Bierman2015). However, if elites tacitly or explicitly condone such speech, it may enhance the emboldening effect, since in the absence of expedient reinforcement or signals of ‘policing’ norm compliance, individuals may get the impression from elite consensus that the norm is breaking down, which in turn should weaken pressure for conformity with the norm (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). In sum, we expect that when elites condone explicit racial rhetoric, it will accentuate the emboldening effect (Hypothesis 2a), and when they condemn this type of rhetoric, is will attenuate the emboldening effect (Hypothesis 2b).

While we expect these effects on average, the extent to which a condemning signal from elites dampens the emboldening effect may vary across individuals depending on their susceptibility to normative signals, which is captured by the trait of self-monitoring (Gangestad and Snyder Reference Gangestad and Snyder2000). Self-monitoring refers to the extent to which individuals actively monitor and regulate their behavior in response to the social setting. Those who are high self-monitors are more likely to be concerned with whether their interpersonal behavior is appropriate, and are more likely to check their behavior against existing social norms. Scholars have examined this individual difference measure in the domain of racial attitudes. For example, Berinsky (Reference Berinsky2004) found that high self-monitors, who are presumably more attuned to racial egalitarian norms, are more likely to give racially liberal responses on racial resentment and feeling thermometer measures. Weber et al. (Reference Weber2014) found that more diverse racial contexts increase the effect of negative racial stereotypes on racial policy attitudes, but only among low self-monitors. In short, if high self-monitors receive a strong condemning message from other elites, it should reduce the emboldening effect. By contrast, low self-monitors are less concerned with the appropriateness of their behavior, and therefore pay less attention to regulating it. For these individuals, once negative racial attitudes are activated, condemnation by other elites may have little effect on reducing the emboldening effect. We therefore expect that a condemning signal from other elites should only attenuate the emboldening effect among high self-monitors (Hypothesis 3).

Data and Methods

To test these hypotheses, we focus on the 2016 US presidential election and the candidacy of Donald Trump. This serves as a good test case for the emboldening effect because Trump is a quintessential example of an entrepreneurial elite using explicit racial rhetoric on the campaign stump to take advantage of latent prejudice among the public (Sides, Tesler and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018). We conducted a two-wave panel online survey experiment in the spring of 2016 using Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk platform. Wave 1 was conducted between March 19 and April 23 with 1,287 adults throughout the United States. Respondents were recontacted 3 days afterward and invited to participate in Wave 2, and 997 individuals participated.

In Wave 1, we collected standard demographic information (for example, gender, education, age), political orientations (for example, partisanship), measures of self-monitoring, and most importantly, measured each respondent's level of prejudice toward Latinos using a negative stereotype index from the 2008 American National Elections Studies (ANES). In Wave 2, we administered our experiment, followed by a post-treatment questionnaire containing our dependent variables of interest. The purpose of the panel design was to (a) separate in time the measurement of prejudice (Wave 1) and delivery of treatments (Wave 2) to avoid priming racial attitudes immediately prior to the delivery of treatments with varying racial content and (b) use Wave 1 measures of prejudice to test whether exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech in Wave 2 emboldened prejudiced citizens by ‘activating’ an effect of prejudice on outcome variables collected in our post-treatment questionnaire.

Appendix Table A5 presents key demographic information from the sample and compares it to other prominent nationally representative surveys, including an online sample used in a recent study about immigration (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015). The table shows that our sample is similar to these others on many dimensions, though it is slightly more educated, younger and Democratic, which is consistent with other MTurk samples (Berinsky, Huber and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012). While our study is not nationally representative, experimental studies on MTurk often replicate those done on representative samples (Berinsky, Huber and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Mullinix et al. Reference Mullinix2015; Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan2014), and panel studies using national samples are often cost prohibitive. Furthermore, the particular bias in our sample works to our advantage in that a more left-leaning and educated sample should be less likely to be affected by Trump's rhetoric, which provides a more conservative test of our expectations.

Experimental Design

After agreeing to participate in Wave 2, respondents were instructed that they would read a randomly chosen article about the 2016 presidential election that ‘appeared in print within the past three months’. The articles were created by the authors, drawing on real election content, and the experimental treatments were embedded in the articles.

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of six experimental conditions, which are displayed in Table 1 (see Appendix B for the full scripts). All conditions involve exposure to an article on the primary elections that focuses on two candidates – Hillary Clinton and one Republican candidate – and discusses their positions on a political issue. What varies across our experimental conditions is (1) whether the Republican candidate is Jeb Bush or Donald Trump, (2) whether the issue highlighted is campaign finance reform or immigration, (3) whether racially inflammatory statements by Trump are presented and (4) the presence and content of normative signals from other elites concerning statements made by Donald Trump. Thus, our experiment involves a 2 (Republican candidate: Bush/Trump) × 2 (Political issue: campaign finance reform/immigration) × 2 (Trump's racially inflammatory speech: absent/present) × 3 (Elite signals: none/condone/condemn) imbalanced factorial design. The imbalanced nature of the design is induced by the branched nature of treatments (for example, only those exposed to Trump were assigned to the inflammatory speech or elite signals treatment), and the lack of feasibility and/or utility of many of the conditions created by a balanced design.

Table 1. Experimental design

Note: the table describes the varying content of the six different version of the article respondents were asked to read in Wave 2 of our online panel survey experiment.

Our control condition serves as our baseline comparison group, as it enables us to establish the marginal effect of prejudice toward Latinos on our dependent variables in the absence of exposure to Trump, racially inflammatory statements by Trump or any signals from other elites. Individuals in this condition read about Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush's stances on campaign finance, which are not at all linked to race or ethnicity. Our expectation, given the established literature demonstrating broad public compliance with norms of equality and social desirability pressures, is that prejudice will not influence our main outcome variables. More specifically, this condition should not activate the effect of prejudice on evaluations of acceptable public behavior toward a minority, as well as one's own behavior.

Our primary treatment condition – the ‘Trump Prejudice’ condition – involves Trump as the Republican candidate contrasted with Clinton, deals with the topic of immigration, and exposes respondents to racially inflammatory statements made by Trump against Mexican immigrants in his announcement speech: ‘When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending the best. They're sending people that have lots of problems and they're bringing those problems. They're bringing drugs, they're bringing crime. They're rapists.’ This condition enables us to test the emboldening effect hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). We expect that individuals exposed to this condition should be more likely to bring their prejudice to bear on their evaluations of publicly acceptable behavior toward minorities and in their own behavior.

One concern in the design stage of our study was that differences observed on outcome variables between the Trump Prejudice and Control conditions could be due to exposure to racially inflammatory speech, but could also be due to priming racial attitudes via discussion of immigration. To address this concern, we included an ‘Immigration Prime’ condition featuring Clinton versus Bush and discussion of immigration; this condition enables us to assess the prejudice-activating effect of mentioning immigration without racially inflammatory content. Another concern is that, at the time of our study, Trump's racially controversial comments and positions were likely widely known, as his initial and perhaps most controversial comments about Mexican immigrants (for example, Mexico sending criminals, drug dealers and rapists) were made in speeches delivered during the summer and fall of 2015. Thus it is possible that mention of Trump alone may embolden prejudice by activating in citizens minds' his known position on immigration and corresponding inflammatory statements. We therefore included a ‘Trump Prime’ condition that mentions Trump but does not discuss immigration and instead relays his stance on campaign finance reform.

The final two conditions in our experiment include the same content as the Trump Prejudice condition but add a short paragraph to the end of the article conveying to readers diverging normative signals from political elites regarding the statements made by Trump. The ‘Trump Condone’ condition highlights that the Republican Party has maintained support for Trump and that both parties have remained silent with respect to accusations of prejudice and hate speech, while the ‘Trump Condemn’ condition indicates that leaders in both parties have strongly condemned his comments as ‘prejudiced’ and ‘borderline hate speech’. The Trump Condone condition enables us to test the hypothesis that when other elites condone such speech, it will only exacerbate the effect of prejudice on our dependent variables of interest (Hypothesis 2a), while the Trump Condemn condition diminishes the emboldening effect (Hypothesis 2b). We used bipartisan sources to create treatments that would be similar in strength but mirror images of each other. As we noted earlier, a message that Democrats condemn Trump's speech is not likely to be very effective among Republicans. However, condemnation coming from members of one's own party should be more persuasive. On the flip side, prejudiced speech that is condoned by members of one's own party may not send a strong signal of acceptance since individuals might realize the strategic interests of the party. However, if Democrats also stay silent in the face of such speech, it sends a stronger signal that the norm environment may be shifting.

Measures

After reading the assigned article, respondents were given a post-treatment questionnaire that included our dependent variables of interest. First, we presented respondents with an item measuring their normative evaluations of the prejudiced behavior of an actor in a short vignette. Secondly, we gave respondents the opportunity to express their prejudice via a quasi-behavioral item. Focusing now on the former item (we discuss the quasi-behavioral measure later), respondents were asked to evaluate the acceptability of the behavior of the primary actor depicted in the vignette. This vignette approach has been used in research that explores the impact of exposure to media with disparaging content toward specific groups (for example, racial minorities, women, homosexuals) on the perceived bounds of acceptable behavior and tolerance of discriminatory events (Bill and Naus Reference Bill and Naus1992; Ford, Wentzel and Lorion Reference Ford, Wentzel and Lorion2001; Ford et al. Reference Ford2008).Footnote 16 Our main vignette of interest was as follows:

Vignette 1: ‘Darren Smith is a middle manager at an accounting firm and has been working at the firm for nearly 8 years. One part of Darren's job is to supervise the new interns for the accounting firm. While Darren usually likes the interns, he does not like a new intern named Miguel. Darren regularly throws away Miguel's leftover food in the break-room fridge, claiming that “Miguel's food is greasy and smells up the fridge.’

After reading this vignette, respondents were asked how acceptable or unacceptable they found the behavior to be on a scale from 1 (completely unacceptable) to 5 (completely acceptable); we also included a midpoint of 3 (neither good nor bad). The purpose of this vignette was to depict a mundane situation in which an individual (a) harbors prejudice and (b) engages in discriminatory behavior: ‘Darren’ is described as (a) distinctly disliking an individual whose name signals Latino ethnicity and (b) engaging in behavior that scholars define as ‘active harming’ behavior (Cuddy, Fiske and Glick Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2007), which is intended to harass, disparage or physically harm members of a disliked group. There was strong consensus in our sample about the unacceptability of the vignette actor's behavior: approximately 49 per cent of our sample viewed it as ‘completely unacceptable’ and 42 per cent viewed it as ‘unacceptable’. However, 9 per cent of the sample reported the actor's behavior as either normatively neutral or acceptable; thus a small subset of respondents expressed varying degrees of tolerance of prejudiced behavior. We use respondents' normative evaluations of the behavior of ‘Darren’ as our main measure of tolerance of prejudiced behavior. The critical questions for our analysis are whether respondents' existing prejudice is predictive of such tolerance, and whether prejudice becomes more predictive of such tolerance following exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech.

The primary independent variable in our analyses is a measure of prejudice toward Latinos administered in Wave 1 of our survey. We utilized a negative stereotype index adapted from the 2008 ANES, which asks respondents to report how well the words ‘intelligent’, ‘lazy’, ‘violent’ and ‘here illegally’ describe ‘most Hispanics’ in America, on a five-point scale. As responses to these items scale well together (α = 0.73), we constructed a scale labeled Prejudice that, for ease of interpretation, was coded to range from 0 (low prejudice) to 1 (high prejudice). Importantly, there are no significant differences in Prejudice across experimental conditions (see Appendix C). We use negative stereotypes to assess levels of prejudice because they are a common measure of prejudice and are less controversial than measures of symbolic racism (Sears Reference Sears, Katz and Taylor1988) or racial resentment (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996), which potentially conflate racial animus with non-racial political ideology (Huddy and Feldman Reference Huddy and Feldman2009; Piston Reference Piston2010).

Results

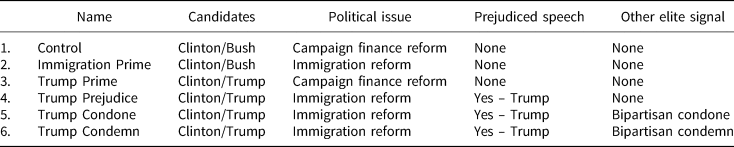

We analyzed the effect of Prejudice on respondents' normative evaluations of the prejudiced vignette actor's behavior across each of our experimental conditions.Footnote 17 The results from our analysis are presented in Figure 1 (full results in Appendix Table A1). Panel A plots the coefficients for the effect of Prejudice from ordered logistic regression analyses, Panel B depicts the effect sizes via first differences in the predicted probability of viewing the vignette actor's behavior as either ‘Typical – Neither Good nor Bad’ or ‘Completely Acceptable’ associated with increases in Prejudice, and Panel C presents the effects of the experimental treatments (compared to control) among respondents low and high in Prejudice. There are two pieces of information to attend to when viewing the results in the panels: (1) effects that are different than zero and (2) effects that are different from the control condition.

Figure 1. Marginal effect of prejudice on normative evaluations of prejudiced behavior

Note: Panel A. Ordered logit coefficients. Panel B. First differences in predicted probabilities. Panel C. Treatment effects by respondent prejudice. Vertical lines in each panel represent 90 per cent confidence intervals for point estimates.

Beginning with Panels A and B and respondents in the control condition, we find that the marginal effect of Prejudice is effectively zero, indicating that the perceived acceptability of the behavior of ‘Darren’ toward ‘Miguel’ did not systematically differ across low- and high-prejudice respondents. This null effect is important, as it reinforces the conventional wisdom that the prevailing norm environment is one in which high- and low-prejudice citizens are mutually aware of equality and tolerance norms and evince shared perceptions, or at least shared reported perceptions, of the unacceptability of overtly prejudiced behavior. For example, on the five-point scale of the dependent variable, those scoring above the 75th percentile of Prejudice reported a mean acceptability rating of 1.46, while those scoring below the 25th percentile reported a mean acceptability rating of 1.50. In short, while we contain prejudiced respondents in our data, in the absence of racially inflammatory elite speech or cues priming racial attitudes, they do not express their prejudice by deeming the occurrence of prejudiced behavior acceptable.

When we look at the effects of prejudice in the other experimental conditions, the picture changes substantially. Simply priming immigration in respondents’ minds is not sufficient to significantly activate prejudice into shaping perceptions of acceptable behavior. Interestingly, priming Trump with no explicit discussion of immigration or exposure to his racially inflammatory statements enhances the operation of prejudice in shaping perceptions of acceptable behavior. However, the effect is only marginally significant (p = 0.077) and substantively negligible when focusing on the change in the probability of perceiving the actor's behavior as ‘completely acceptable’ (that is, only a 0.03 increase). However, the Trump Prime condition does activate a more substantively meaningful effect of Prejudice on normative indifference, as an increase in Prejudice in this condition is associated with a 0.10 increase in viewing the vignette actor's behavior as ‘Neither good nor bad’. This finding reinforces our concern about the mounting association between Trump and race in the minds of Americans at the time of this study.

Moving on to the Trump Prejudice condition, the effect of Prejudice is significant (p = 0.025), lending support to Hypothesis 1. However, the effect is negligibly different than that in the Trump Prime condition – both in terms of coefficient and first-difference estimates. This finding is noteworthy, as it indicates that most of the prejudice-activating effect of Trump appears to be achieved by simply mentioning his name; mentioning Trump's racially inflammatory statements has very little additional impact on activating prejudice.

However, the effect of Prejudice is most pronounced in the Trump Condone condition, in which respondents are exposed to racially inflammatory speech and indications that other elites tacitly condone Trump's speech. In Panel A, the effect of Prejudice is not only farthest from zero, it is the only effect estimate that significantly differs from that of Prejudice in the control condition (see Table A1). Substantively, prejudice has a large effect in the Trump Condone condition: a shift from low- to high-prejudice individuals is associated with a 0.16 increase in the probability of perceiving the vignette actor's behavior as completely acceptable, and a 0.25 increase in perceiving the behavior in a normatively neutral light. These are striking effects. For example, when considering the change in the probability of perceiving the vignette actor's behavior as ‘completely acceptable’, the effect of Prejudice in the Trump Condone condition is 160 times larger than the effect observed in the control condition. Additionally, the effect of Prejudice in the Trump Condone condition is meaningfully distinct from those in the Trump Prejudice condition. While not statistically different, the differences are substantively meaningful, as the change in the probability of deeming the vignette actor's behavior ‘neither bad nor good’ (‘completely acceptable’) increases from 0.11 (0.04) in the Trump Prejudice condition to 0.25 (0.16) in the Trump Condone condition, representing a 130 (300) per cent increase in the size of the effect. This finding provides strong support for Hypothesis 2a.

Turning finally to the Trump Condemn condition, we see that when exposure to Trump's inflammatory statements is coupled with a condemning signal, the effect of Prejudice shrinks from that observed in the Trump Condone condition and is roughly comparable to the effect observed in the Trump Speech condition. Prejudice still affects views of publicly acceptable behavior toward minorities, and that effect is not diminished relative to just hearing the explicitly racial speech. We therefore find little support for Hypothesis 2b. However, the effect of Prejudice in the Trump Condemn condition is not statistically different from that observed in the control condition, indicating that when exposure to Trump and his racially inflammatory statements is coupled with condemning signals from political elites, the perceptions of high- and low-prejudice citizens differ little from those observed in a context devoid of Trump or his racially controversial speeches.

In addition to illustrating how experimental manipulation of elite communication changes the effect of respondents' pre-existing Prejudice on their normative evaluations, we can also estimate the effect of our experimental treatments among respondents with low and high levels of Prejudice. The value of this analysis is that it conveys information about who is driving the results in Panels A and B – those who are low or high in prejudice. To ensure sufficient statistical power, we define individuals with low (high) prejudice as those below (above) the 25th (75th) percentile value of Prejudice. We estimated separate regression models among those with low and high levels of Prejudice and present the results in Figure 1 Panel C, noting that we use the control condition as the comparison condition for estimating the effect of each treatment condition. As illustrated in Panel C, the results in Panels A and B are driven by high-prejudice respondents, as there are no statistically significant treatment effects among low-prejudice respondents. By contrast, among high-prejudice respondents, we observe significant effects for the Trump Prejudice and Trump Condone treatments. These results are key, as they demonstrate that the ‘activation’ of Prejudice observed in Panels A and B is brought about by the systematic alteration of the perceived acceptability of prejudiced behavior among high-prejudice individuals in response to racially inflammatory elite communication. Importantly, the findings in Panel C align with recent work demonstrating that Trump's vitriolic campaign messages activated the support of voters with a ‘reservoir’ of existing prejudice toward ethnic and religious minorities (Sides, Tesler and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018, 7). Panel C also demonstrates that, among high-prejudice individuals, the Trump Prime treatment failed to exert a significant effect. This is noteworthy, as it suggests that the marginally significant effect of Prejudice observed in the Trump Prime condition in Panels A and B does not translate into a significant effect for the Trump Prime among high-prejudice respondents. Instead, we only find significant effects for the Trump Prejudice and Trump Condone treatments, suggesting that when focusing on the most prejudiced individuals, the emboldening of such prejudice requires exposure to inflammatory rhetoric.

In sum, our findings provide unprecedented causal evidence that Trump's racially inflammatory speech emboldened individuals to express their prejudice (that is, a ‘Trump effect’). Our findings reveal that in a context devoid of prejudiced elite speech (our control condition), prejudiced individuals appear to suppress expressing their prejudice by actively denouncing prejudiced behavior. However, we find that this ‘suppression effect’ slowly unravels and gives way to tolerance and acceptance of prejudiced behavior following exposure to racially inflammatory speech by a prominent political elite. As our study occurred several months after Trump's infamous ‘rapists’ comment and ‘build a wall’ speech, it is likely that many Americans were aware of Trump and his inflammatory statements toward Mexican immigrants. As suggestive evidence of this, we observe a prejudice-activating effect of the mere mention of Trump in a treatment that was devoid of any racial content. Perhaps most important, we find that the emboldening effect of an elite like Donald Trump is most pronounced in a context where citizens are given signals that the political system tolerates prejudice by allowing candidates who engage in prejudiced speech to continue their campaigns without sanction. Last, we find that condemnation by other elites does little to suppress prejudice once it is activated.

Placebo Test

Our post-treatment questionnaire included another (placebo) vignette that depicted an actor engaging in unprejudiced behavior toward a person whose race is unknown (he or she was not signaled by name).Footnote 18 In this second vignette, the actor, Nancy, is admonishing a teenage boy for violating norms pertaining to public health etiquette – in this case, for not covering his mouth when coughing in public. As this vignette does not pertain to racial equality or tolerance norms, we do not expect prejudice to influence evaluations of the vignette actor's behavior. Nor do we expect to observe an emboldening effect via a magnification of the effect of prejudice following exposure to our experimental treatments.

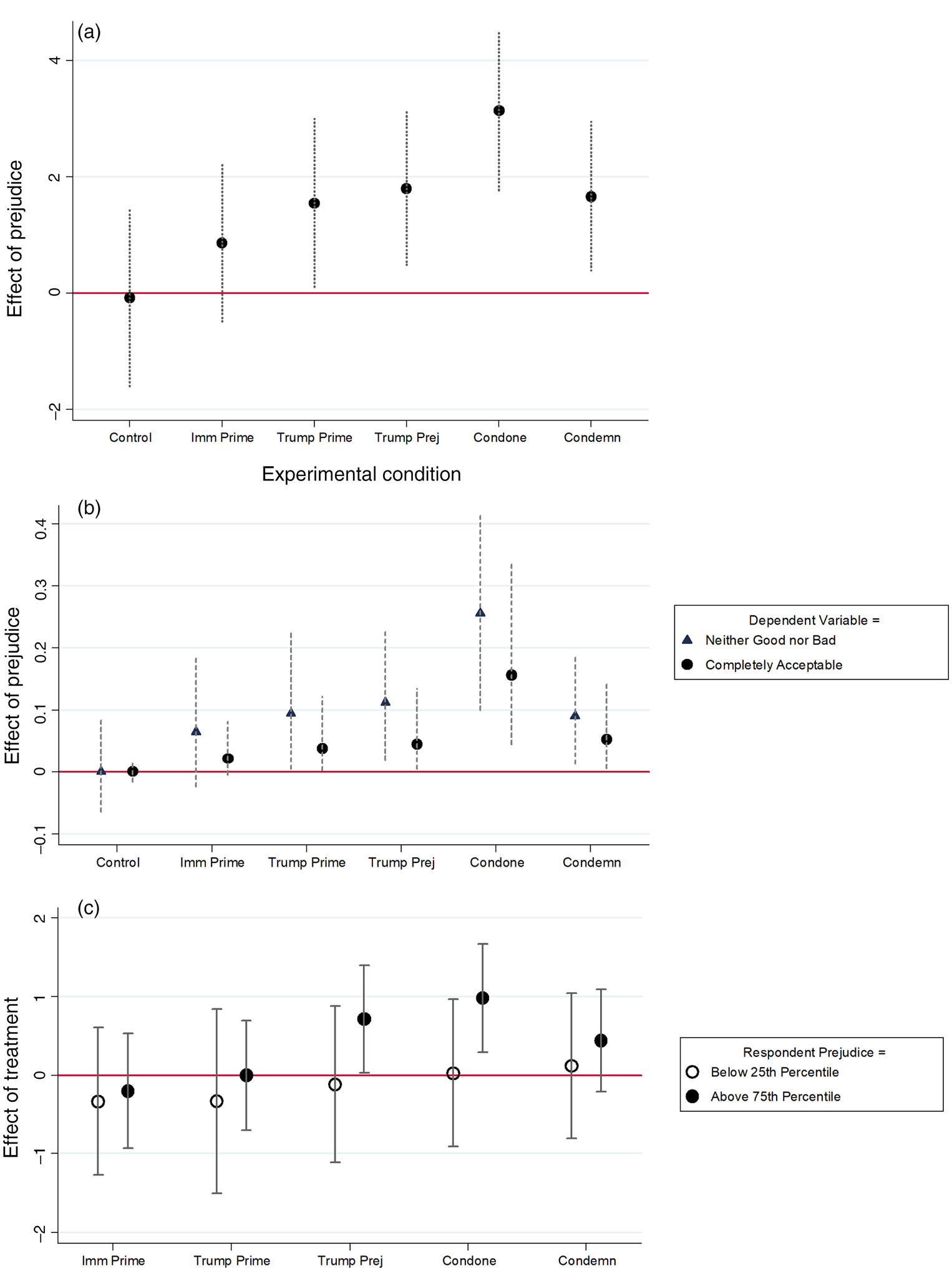

Figure 2, Panel A reports the effects of Prejudice on evaluations of the acceptability of Nancy's behavior across our experimental conditions (the full results are reported in Table A2). We expect Prejudice to exert few or no effects, as the target of Nancy's behavior is not racially identified, and thus there is no potentially racially motivated aggressive behavior to embolden. This is mostly what we find, as Prejudice fails to exert a statistically significant effect in every condition except the Trump Prime condition. Interestingly, simply priming Trump in respondents' minds (that is, in treatments that do not contain explicit racial content) led more prejudiced respondents to deem Nancy's reprimand of a teenage boy more acceptable. One interpretation is that, if one were to view Nancy's behavior as more frank, aggressive or rude, exposure to Trump appears to lead prejudiced citizens to view such behavior as more acceptable. However, this effect does not hold in any other condition, especially not the other Trump Prejudice conditions, which suggests that this finding may simply be a fluke. It is important to emphasize that we do not observe the pattern of emboldened effects of Prejudice in the second vignette that we observed with the first vignette. Further, when performing difference tests on the effect of Prejudice on evaluations of the behavior of Darren versus Nancy by experimental condition, the results in Figure 2, Panel B reveal a significant difference in the Condone condition – indicating that Prejudice was significantly less operative in shaping evaluations of Nancy's behavior than it was for Darren's behavior.

Figure 2. Effect of prejudice on normative evaluations of non-prejudiced behavior (placebo test)

Note: Displayed effects (Panel A) and differences in slopes (Panel B) are ordered logistic regression coefficients with 90 per cent confidence intervals.

Quasi-Behavioral Measure

We now turn to the second component of the emboldening effect – actual behavior. Here, we are interested in assessing whether our findings extend to actions that express one's own prejudice. To capture this effect, we included a quasi-behavioral item in our post-treatment survey that enables us to observe respondents' willingness to engage in negative behavior toward a racial minority. Following the vignettes, we asked respondents to evaluate the quality of the survey:

Our research team is currently trying to get feedback on our surveys. We'd like to know how well you think this survey was organized and administered. Each of our surveys are created and run by a project leader. The survey you are currently taking –MEDIA, THE 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN and CURRENT EVENTS SURVEY – is being administered by project leader – JUAN RAMIREZ (emp. code 3425).

The purpose of this question was to lead respondents to believe that they could provide potentially consequential input toward the performance evaluation of a putatively Latino worker. Respondents were asked to rate the survey administered by ‘Juan’ on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). Our primary interest here is in observing whether the pattern of effects we observed for Prejudice on tolerance of discriminatory behavior (by ‘Darren’) extend to a quasi-behavioral measure.

We conceptualize this item as quasi-behavioral because we are giving respondents an opportunity to engage in harming behavior by providing a negative performance evaluation, which they were led to believe is consequential outside of the survey response context. While there is room for debate on whether providing a performance evaluation is a behavior, this item undeniably provides respondents with a clear opportunity to express their prejudice against Latinos toward an individual who is putatively Latino. As such, we view this item as a reasonable and innovative method of capturing the active expression of prejudice. We expect prejudiced individuals to be emboldened to express their prejudice via negative performance evaluations following exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech (Hypothesis 1), and will be most emboldened when such speech is accompanied by the condone signal (Hypothesis 2a).

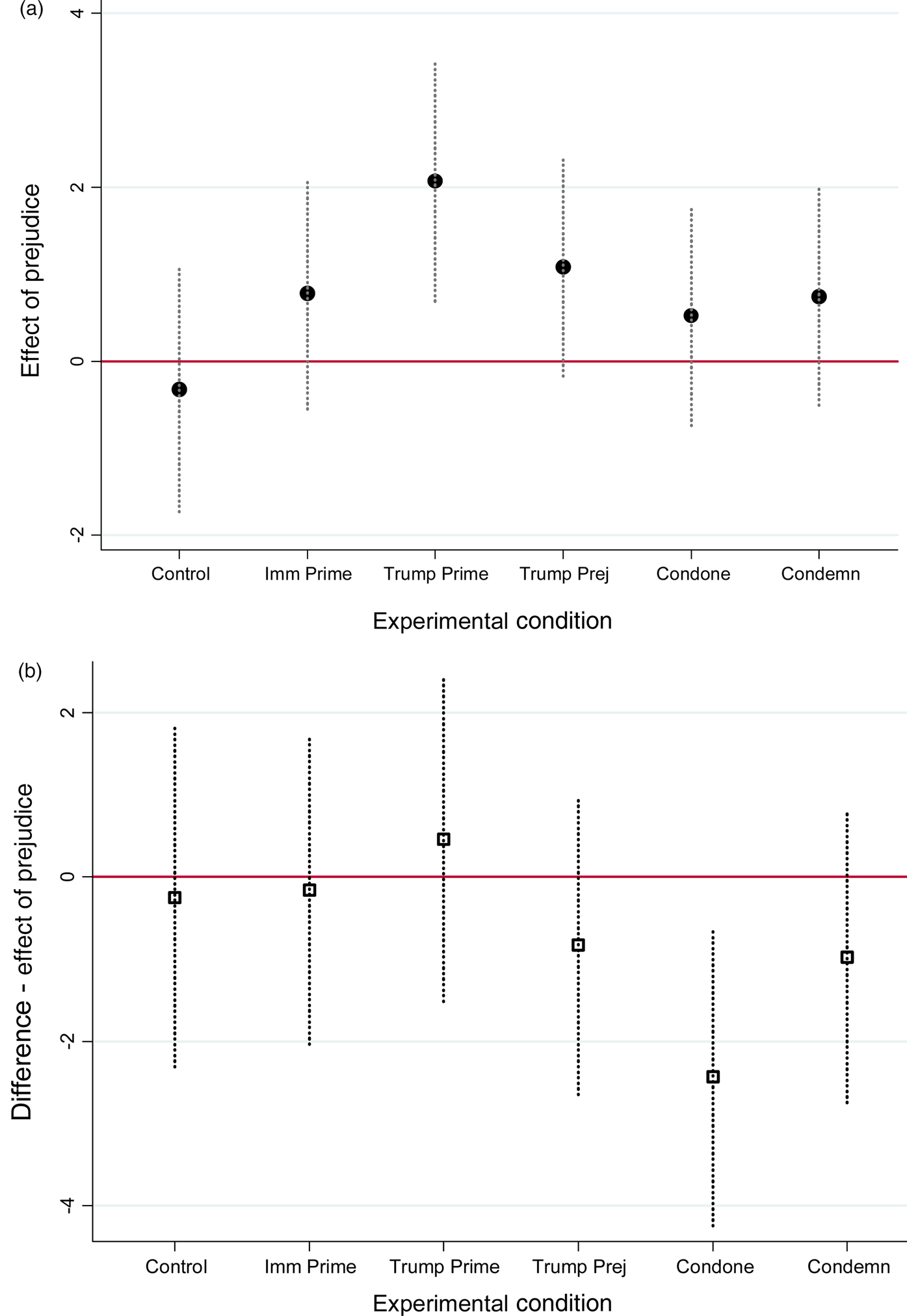

This is precisely what we find. Figure 3, Panels A and B display the results of our regression analysis (full results in Table A3). The effect of Prejudice in the control condition is negative but statistically insignificant, while it is significant in all other experimental conditions and is associated with more negative evaluations of Juan. The only condition in which the confidence intervals for Prejudice do not overlap with the control group is the Trump Condone condition, which indicates that the effect of Prejudice results in a significantly more negative performance evaluation of ‘Juan’ in the Trump Condone condition than in the Control condition. Figure 3, Panel B shows that Prejudice has the largest effect in the Trump Condone condition, as it is associated with a dramatic 0.67 decrease in the probability of providing a ‘Very Good’ performance evaluation. While the effect of Prejudice in the Condone condition does not differ statistically from its effect in the Trump Prejudice condition, it is worth noting that the difference between the two effects is substantively significant. Indeed, the effect of Prejudice is nearly 0.20 larger in the Trump Condone condition than in the Trump Prejudice condition, or roughly 40 per cent larger, which is a non-negligible increase in effect size.

Figure 3. Effect of prejudice on reported job performance of Latino survey administrator

Note: Panel A. Ordered logit coefficients. Panel B. First differences in predicted probability. Dashed vertical lines in both Panels represent 90 per cent confidence intervals for point estimates. Panel B depicts first differences in the probability of giving ‘Juan’ a ‘Very Good’ performance evaluation.

As was the case with respondents' normative evaluations of the prejudiced vignette actor's behavior, exposure to Trump's racially inflammatory speech in conjunction with condemning signals does nothing to diminish the effect of prejudice on harm-intending behavior, which is contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 2b). In sum, the results in this section reveal that the pattern of effects observed for tolerance of prejudiced behavior extends to the personal expression of prejudice.

Further Unpacking Elite Condemnation

Our results so far provide suggestive evidence that prejudiced elite speech, as well as a political environment that tacitly tolerates such speech, can embolden the prejudiced. One result that has come up short with respect to our hypothesis is the relatively weak effect of the condemn signal in reducing the expression of prejudice. While we observed an attenuation of the effect of Prejudice in the Trump Condemn condition relative to the Trump Condone condition, we do not observe noticeable differences in the effect of Prejudice between the Trump Prejudice and Trump Condemn conditions. This finding runs counter to our general expectation that providing citizens with clear and unified elite condemnation of racially inflammatory speech would undermine any emboldening effect observed. However, we also expected this effect to hold primarily among high self-monitors (Hypothesis 3).

Thus one key test of our results, in terms of both evaluating the efficacy of our condemn signal and corroborating a key mechanism underlying our findings, is to observe whether responses to the condemn signal vary by the respondents’ level of self-monitoring. Such a finding would corroborate the mechanism underlying our findings by demonstrating that an individual difference factor related to (a) norm attentiveness and (b) norm compliance underscores respondents’ reactions to our condemn treatment. Our Wave 1 pre-treatment questionnaire included four items from the self-monitoring scale taken from Terkildsen (Reference Terkildsen1993). These items asked people to indicate whether the following statements are ‘true or false as it applies to you’:

When I am uncertain how to act in social situations I look to the behavior of others; I would not change or modify my opinions in order to please someone else or win favor; My behavior is usually an expression of my true attitudes and beliefs; and, I am not particularly good at making other people like me.

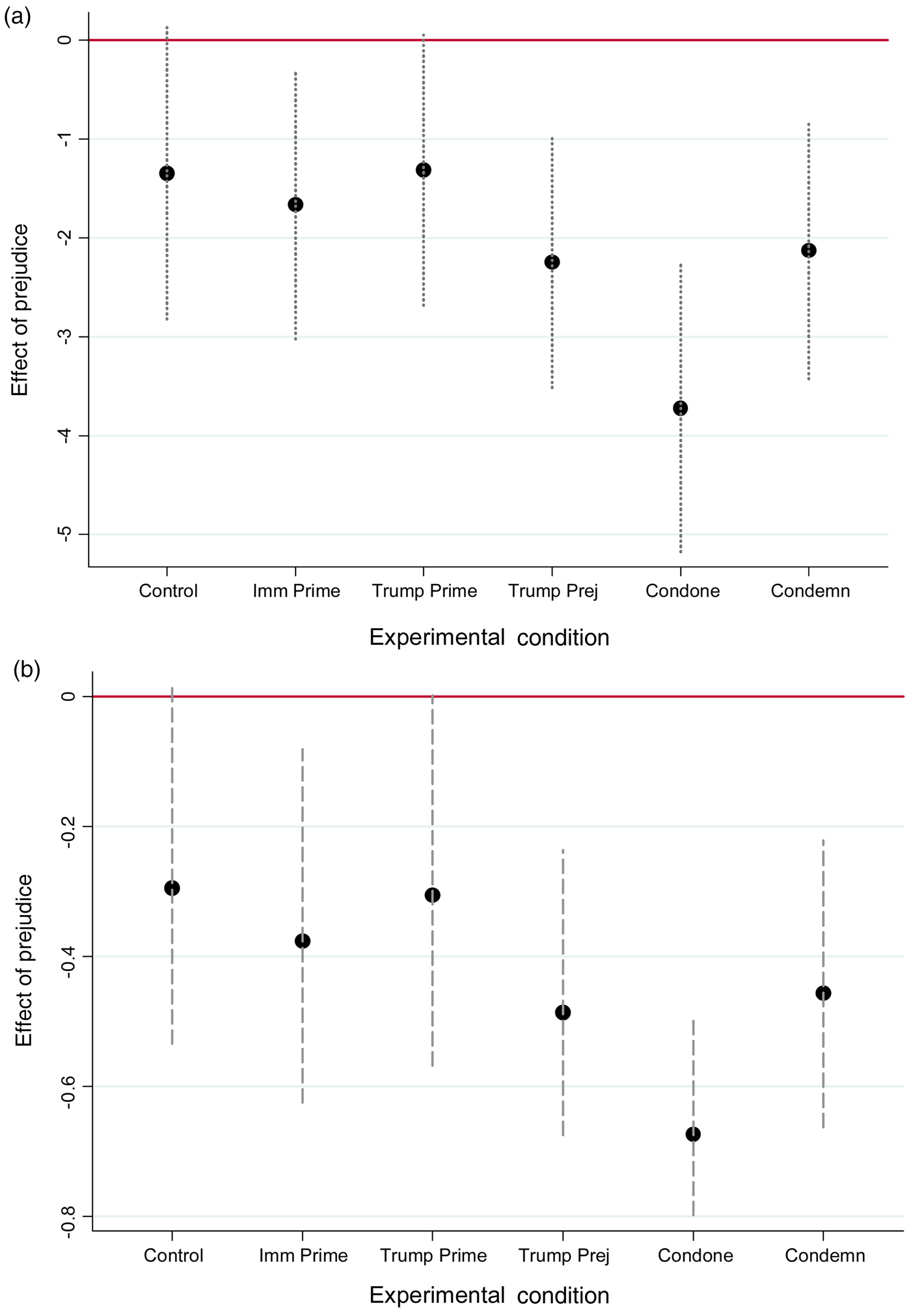

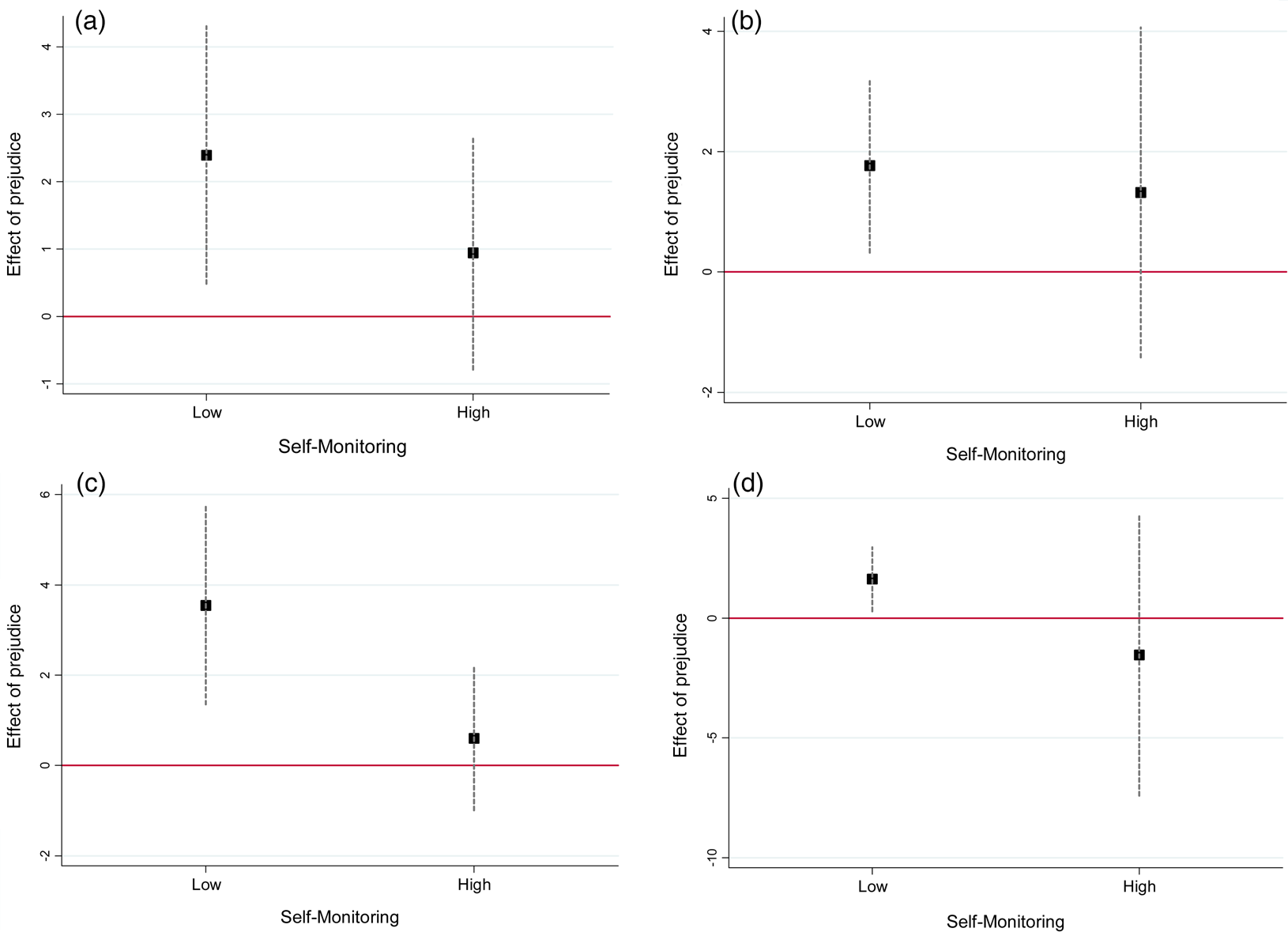

Figure 4 displays the estimated effect of Prejudice among those in the Trump Condemn condition separately for low- and high-self-monitoring responses to each of the four self-monitoring items (full results available in Appendix Table A4).Footnote 19 The dependent variable in this analysis is normative evaluations of the prejudiced vignette actor's (‘Darren’) behavior. In other words, we reanalyze the results presented in Figure 1 for those in the Condemn condition by level of self-monitoring. Figure 4 shows that, among those offering the low-self-monitoring response to each question, Prejudice exerts a positive and significant effect on the reported acceptability of prejudiced behavior. However, among those offering the high-self-monitoring response to each of the four items, we observe consistent null effects of Prejudice. Thus, while Prejudice exerts a positive and significant effect in the Trump Prejudice condition, this effect is only retained in light of the added Condemn treatment among respondents who evince a lack of concern for social norms and an unwillingness to mold their behavior to prevailing social norms or situational behavioral expectations. Since those high in self-monitoring are responsive to this signal, their pre-existing Latino prejudice goes underground, such that it does not affect their evaluations of prejudiced behavior toward a Latino target.

Figure 4. Effect of prejudice on normative evaluations of prejudiced behavior in Trump condemn condition, conditional upon self-monitoring

Note: Panel A. ‘Look to behavior of others’. Panel B. ‘Good at making others like me’. Panel C. ‘Change opinions to please others’. Panel D. ‘My behavior is not expression of true attitudes’.

The findings in Figure 4 are important for our analysis because they validate our interpretation of the mechanism underlying our findings. We find that exposure to Trump's inflammatory speech altered prejudiced respondents' perceptions of norms with respect to engagement in prejudiced behavior. We also found that this effect was largest when coupled with a condoning signal, and basically unaltered when coupled with a condemning signal. This final set of results indicates that among the respondents who were presumably the most concerned about compliance with norms, exposure to Trump's racially inflammatory speech coupled with condemnation by other elites makes prejudice inactive. These results enhance our confidence that our treatments are indeed manipulating perceived norms, and they fortify our overall findings by illustrating the capacity of prejudiced elite speech and its toleration within the political system to embolden the prejudiced, especially prejudiced citizens who are not overly concerned about complying with normative expectations. Interestingly, when we reanalyze the effect of Prejudice among those in the Control condition, we do not find evidence of heterogeneity by level of self-monitoring. These results depict a situation in which the prejudiced – including those low in self-monitoring – appear to suppress the expression of their prejudice. However, once the floodgate on their prejudice is lifted by exposure to racially inflammatory elite speech, it is not easily re-encapsulated, particularly with respect to prejudiced citizens who are unconcerned about violating social norms. To be sure, while decades of prevailing norms of tolerance and equality appear to have disciplined the expression of prejudice among low-self-monitoring, high-prejudice citizens, our results foreshadow a possible scenario in which a provocative elite engaging in racially inflammatory speech can undermine the accumulated suppressive effect of decades-old norms.

Conclusion

Our findings lend empirical support to anecdotal claims of a ‘Trump effect’, or what we call an emboldening effect. Exposure to Trump's racially inflammatory speech caused individuals in our study to bring their prejudice to bear on perceptions of the norm environment toward Latinos, as well as in their behavior. What is most striking about our findings is that the emboldening effect of Trump's rhetoric is the most pronounced when other elites in the political system tacitly condone such speech. When other elites stay silent, it potentially signals to those who are prejudiced that the norm environment is shifting and that it is no longer unacceptable to publicly express prejudice. In other words, it gives license to individuals who harbor prejudice to express it. Exposure to elite condemnation of such speech only suppressed prejudice among high self-monitors.

Our findings connect well with prior work on the effect of implicit and explicit racial cues in campaigns. Like some newer work in that area (Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2017; Reny et al. Reference Reny, Valenzuela and Collingwood2019), we find that it is no longer the case that explicit racial cues fail to activate negative racial attitudes. While we only considered rhetoric by Trump, this other work shows that explicit racial cues by other elites also activate negative racial attitudes in the domain of candidate evaluations. Our study also connects to existing work on the radical right in Europe, which has found that individuals with more negative attitudes toward immigrants have been drawn to radical right parties (for example, Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Ford and Goodwin Reference Ford and Goodwin2017; Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2015), especially those lower in motivation to control prejudice (Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013). However, we depart from this work by considering a new dependent variable – perceptions of the norm environment – and by exploring a quasi-behavioral outcome measure. Our findings show one way in which the rhetoric by leaders of these parties may embolden individuals to express prejudice, even in environments with strong social norms to suppress it. Future work can consider whether explicit racial rhetoric by other elites has similar effects on the types of dependent variables we explore here.

There may be questions of how robust our findings are, given that this is but one study. We believe our findings speak to a growing body of evidence that Trump's rhetoric shifted social norms and emboldened the prejudiced. For example, using a convenience sample recruited on Mechanical Turk before and after the 2016 election, Crandall, Miller and White (Reference Crandall, Miller and White2018) find that after the election, people perceived greater tolerance of prejudice toward the marginalized groups that Trump targeted during his campaign. A similar pre/post survey design by Georgeoc, Rattan and Effron (Reference Georgeac, Rattan and Effron2019) with Survey Sampling International Panelists detected a small but significant increase in gender bias among Trump supporters post-election. Additionally, using survey experiments embedded in the 2016 and 2017 Cooperative Congressional Election Studies, Schaffner (Reference Schaffner2018) finds that individuals exposed to Trump's explicit racial rhetoric toward Mexicans and Muslims were more likely to write offensive content about both of these groups. Finally, Giani and Meon (Reference Giani and Méonforthcoming) show that Trump's election had a contagion effect, increasing self-reported prejudice among citizens in various European nations. Our work provides an important mechanism to explain some of these shifts, whereby Trump's rhetoric activates latent prejudice.

In addition, our study pushes the theoretical envelope forward by considering the role of other elites in this process. Elite communication rarely occurs in a vacuum, especially in today's social media-rich environment. Rather, racially inflammatory statements by prominent elites are likely to be met with some response by other elites in the political system. Our findings reveal that how other elites respond can have important implications for the norm environment. To be sure, while many of Trump's racially inflammatory comments were met with public disapproval from prominent elites on both sides of the political aisle, our findings serve as an important ‘cautionary’ note about the importance of the actions – or inaction – of other elites in managing the norm environment confronting the general public.

We focused our inquiry on elites, given that they are the dominant providers of information about politics (Zaller Reference Zaller1992), carry a certain degree of authority (Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Zaller Reference Zaller1992) and have incentives to activate latent prejudice during elections (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Valentino, Hutchings, and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002; White Reference White2007; cf. Huber and Lapinski Reference Huber and Lapinski2006). However, this process is not necessarily unique to elites. Exposure to explicitly racial rhetoric among members of one's own social network may also generate an emboldening effect. There is some supportive evidence for this in work done in the Western European context. For instance, Muller and Schwartz (Reference Müller and Schwartz2018b) have found that public posts against refugees on the Facebook page of a radical right party are correlated with violence against refugees. Our study was not designed to explore this type of effect, or to compare the effect of explicitly racial rhetoric by elites to non-elites, but we think this is a fruitful line of inquiry for future scholarship.

While we have focused on prejudice toward Latinos as being activated by Trump's explicitly racial rhetoric, especially when other elites condone such rhetoric, it is possible that exposure to Trump's rhetoric leads to more extreme outcomes, such as the dehumanization of targeted minority groups. Some scholars have documented dehumanization language about immigrants in Europe, especially in online content (Musolff Reference Musolff2015). More directly relevant, Kteily and Bruneau (Reference Kteily and Bruneau2017) have shown a strong association between holding blatantly dehumanizing attitudes of Mexican immigrants and support for anti-immigrant policies advocated by Trump and support for his candidacy. Utych (Reference Utych2018) uses an experimental design to show how exposure to dehumanizing rhetoric leads to more restrictive immigration policy preferences, in part through higher levels of anger and disgust in reaction to such rhetoric. Dehumanization rhetoric can also be consequential for other groups such as Muslims (Kteily and Bruneau Reference Kteily and Bruneau2017) and women (Tipler and Ruscher Reference Tipler and Ruscher2019). While these studies do not look at whether the use of dehumanizing rhetoric activates latent prejudice, this would be a fruitful avenue to explore in future work.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JLJUB4 and online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000590

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julie Merseth, John Bullock, James Druckman, Laurel Hardridge-Young, Reuel Rogers, participants at the American Politics workshop at Northwestern University, as well as participants at the UCR Political Behavior conference for helpful feedback. We would also like to thank Jeff Jenkins and the participants at the PIPE Collaborative: Parties and Partisanship in the Age of Trump Symposium at the University of Southern California for their feedback.