Introduction

Authoritarian regimes are widely considered more stable and resilient when ruling elites are organized into a dominant party. Compared with other support institutions such as royal families and armed forces, political parties are uniquely suited for performing critical regime-bolstering functions. It is well documented that party organizations provide a platform for mitigating elite conflict (Brownlee, Reference Brownlee2007; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2008; Reuter, Reference Reuter2017; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012), a mechanism for mobilizing public support (Bladyes, Reference Blaydes2010; Greene, Reference Greene2007; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006) and a coercive tool for suppressing opposition (Slater, Reference Slater2003). Ruling parties’ capacity to perform these functions, however, depends heavily on party strength, defined as the presence of organizational infrastructure that controls decision making and the distribution of resources in the political system. It is along this dimension of party strength that we observe considerable variation across one-party authoritarian regimes (Bader, Reference Bader2011; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Meng, Reference Meng2019; Morse, Reference Morse2015). Whereas some ruling parties demonstrate robust organizational autonomy to dominate policy making and penetrate the society, others fall prey to the influence of individual dictators or the military and play only a marginal role in the political system. How do we account for this variation in authoritarian ruling party strength?

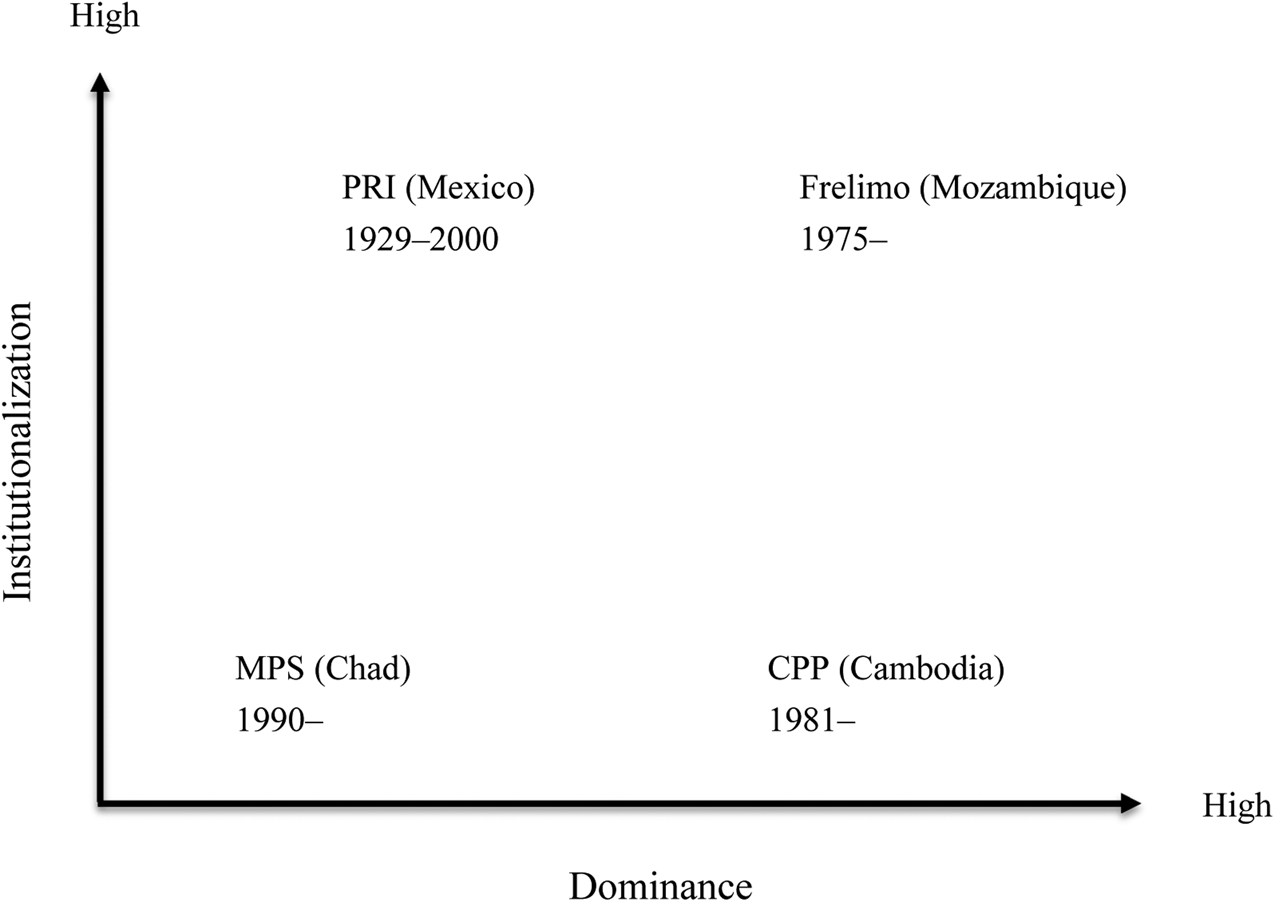

This article develops a general theory to help answer this question. We first articulate a definition of party strength that contains two distinct dimensions: institutionalization refers to the emergence of stable rules and procedures that govern how the party conducts its affairs, while dominance describes the strength of ruling parties relative to other actors in the political system. Using this definition, we argue that party strength stems from a strategic calculation by political actors who weigh the benefits of building a strong party against its costs. While party strength increases the likelihood of gaining and staying in power against powerful opposition, it is financially costly and risks sharing regime spoils with a broader set of elites. We consider three typical strategic environments and analyze how various factors specific to each scenario—the mode of power seizure, resource rents and international pressure—shape the cost-benefit analysis.

Based on the theory, we put forward a series of testable propositions. First, ruling parties that came to power through revolutions tend to develop robust party strength. Second, parties created by sitting dictators tend to develop weak party strength. Third, the amount of natural resource wealth available to a regime is negatively associated with ruling party strength. Fourth, the amount of external democratizing pressure faced by a regime is negatively associated with the dominance dimension of party strength but positively associated with the institutionalization dimension. The empirical section tests these propositions using a dataset that includes all autocratic ruling parties that were in power between 1940 and 2015.

This article makes two major contributions. First, it represents the first attempt to develop a general theory of authoritarian party strength. Existing explanations have taken one of two analytic routes. One approach focusses on how parties were formed and gained power and examines whether these formative events leave lasting imprints on party strength (Geddes, Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018; Huntington, Reference Huntington, Huntington and Moore1970; Smith, Reference Smith2005). This approach says little about what factors other than prior histories shape the development of party strength once parties are in power. The other approach considers party strength as a product of sitting dictators’ strategic projects, empowered or debilitated to serve the rulers’ needs (Reuter and Remington, Reference Reuter and Remington2009; Reuter, Reference Reuter2017; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012). This approach ignores the fact that over 60 per cent of authoritarian parties were not created by incumbent dictators but were founded to seize power through revolution, independence movement or election (Miller, Reference Miller2020: 758). Thus, despite important strengths, neither approach gives a complete account of the diverse strategic environments in which political elites make party-building decisions. Our theory integrates existing knowledge by considering factors specific to distinct stages in the party and regime life cycle. Second, this study is the first to systematically test explanations for party strength. Previous studies have not operationalized the key concepts, converted their arguments into clear hypotheses or tested them against systematic data. We aim to fill these lacunae with sound empirical evidence.

Beyond these major contributions, this study also speaks to two important issues in the literature on party politics. First, many previous studies have singled out nominally democratic institutions such as party and legislature to explain socio-political outcomes in autocracies (Pepinsky, Reference Pepinsky2014). Barbara Geddes's (Reference Geddes1999) classification of non-democracies into single-party, military and personalist regimes has triggered a large volume of studies that associate party-based autocracies with a variety of positive outcomes ranging from regime durability (Gandhi and Przeworski, Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Gandhi, Reference Gandhi2008; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2008) and intra-elite harmony (Boix and Svolik, Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Brownlee, Reference Brownlee2007) to reduced repression (Davenport, Reference Davenport2007) and women's rights provision (Donno and Kreft, Reference Donno and Kreft2019). These works have paid far less attention to whether party institutions really “bite”—namely, whether they are strong enough to cultivate elite support or provide extensive linkages to society. Our research joins a new wave of studies that explain why institutions in some autocracies have grown more impersonal, durable and effective, while others have not.

Second, this article speaks to the rich literature on party institutionalization in the developing world, especially in the consolidation of new democracies (Ishiyama, Reference Ishiyama2008; Mainwaring and Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Randall and Svåsand, Reference Randall and Svåsand2002; Wahman, Reference Wahman2014). While it is widely agreed that party institutionalization facilitates democratic consolidation, the implications of strong parties for the fate of autocracies are more complicated. Paradoxically, the same institutions that increase authoritarian stability may also weaken the ruling party's will to stay in power at all costs (Slater and Wong, Reference Slater and Wong2013; Thompson and Kuntz, Reference Thompson, Kuntz and Andreas2006; Wahman, Reference Wahman2014). When institutionalized party regimes are hit by adverse events such as electoral setback and economic crisis, they will be more likely to tolerate democratic reforms. This is because strong parties have more confidence that they possess the organizational resources to remain a viable opposition and fight back to power under democratic conditions.

Authoritarian Party Strength: Definition and Measurement

The spread of democracy during the end of the twentieth century was met with the simultaneous expansion of party-based autocracies, which have now become the most common form of authoritarian rule (Magaloni and Kricheli, Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010). Party-based regimes display great diversity in terms of the ruling party's role in the political system. Indeed, the institutional variety within party-based autocracies may be as great as that between them and military regimes or monarchies. In his classic study on one-party systems, Huntington (Reference Huntington, Huntington and Moore1970) argued that modern authoritarian regimes, facing a high level of mass mobilization, have little choice but to organize a political party through which potentially threatening political actions could be channelled. Since then, the party's role in sustaining authoritarian order has received a great deal of academic attention, and most scholars agree that “in the longer run . . . the strength of an authoritarian regime will in large measure depend on the strength of its party” (Huntington, Reference Huntington, Huntington and Moore1970: 9). Despite this broad consensus, there is far less accepted wisdom on the sources of such strength.

Where does the strength of ruling parties come from? To answer this question, it is necessary to present a definition of party strength that can be operationalized. Existing studies have mainly conceptualized party strength along two closely related dimensions: institutionalization and dominance. Institutionalization refers to the emergence of stable rules and procedures that govern how the party recruits and promote its members, mobilize social support and make decisions (Basedau and Stroh, Reference Basedau and Stroh2008; Huntington, Reference Huntington1968; Levitsky, Reference Levitsky1998; Meng, Reference Meng2019; Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Randall and Svåsand, Reference Randall and Svåsand2002). An institutionalized party develops rules that can reach a delicate balance between resilience and flexibility; that is, party rules should be persistent enough to prevent any attempt to increase personal power over the party apparatus (Randall and Svåsand, Reference Randall and Svåsand2002: 13) but also adaptable enough to respond effectively to changes in the external environment (Huntington, Reference Huntington1968: 13–17).

Dominance describes the strength of ruling parties relative to other actors in the political system such as personalist leaders, the state bureaucracy, the military and traditional social groups. Strong parties are highly autonomous organizations immune from external interference with their operations. Indeed, these parties dominate other political groupings and control key political functions (Bader, Reference Bader2011; Huntington, Reference Huntington, Huntington and Moore1970: 6–7; Morse, Reference Morse2015). Weak ruling parties, by contrast, have little influence over state administration and/or are vulnerable to the threat of military coup d’état. In short, they lack the ability to act with a degree of freedom to “shape wider social processes and structures” (Isaacs and Whitmore, Reference Isaacs and Whitmore2014: 703).

In light of this two-dimensional view of party strength, we propose a few observable criteria for measuring this concept. The institutionalization dimension can be captured by three major indicators: de-personalization, cohesion and linkage to society. First, de-personalization entails the development of impersonal rules that generate routinized behaviour and constrain the discretion of individual leaders. In highly personalized parties, the leader constantly intervenes in the routine operation of the party bureaucracy, appoints family members and friends to important posts, and refuses to be bound by codified succession rules (Zeng, Reference Zeng2020). De-personalization is thus the process by which powerful executives are gradually tamed by the iron cage of party rules.

Second, cohesion refers to the sense of unity and solidarity that enables the party to act as a unified whole. Party organizations inculcate politicians with party values, facilitate coordination and provide the tools for monitoring individual party members. As a result, members of strong parties demonstrate strict discipline in the making and implementation of major policy initiatives. They are also more resistant to opportunistic behaviour such as switching allegiance to other parties between elections (Bizzarro et al., Reference Zeng2018: 8).

Third, linkage to society reflects the party's ability to mobilize mass support with its local organizations. Strong parties have well-equipped and staffed branch offices across the country, including in the rural hinterland, and perform regime-supporting functions both during and between periods of electoral campaigns (Basedau and Stroth, Reference Basedau and Stroh2008: 13–14; Morse, Reference Morse2015). Local party branches cultivate popular support by doling out rewards to cooperative citizens in the form of jobs, cheap credits and business licences (Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006). Combined with activities such as gathering information, spying on political opponents and holding campaign rallies, a grassroots presence helps establish the party's existence in the public imagination and maintain a stable segment of partisan followers.

The dominance dimension can in turn be measured by two criteria. The first concerns party control over important positions in the state administration. With strong ruling parties, elites obtain influential positions in the state by rising through the ranks of the party apparatus. Junior members understand that providing services for the party is the prerequisite for a desirable political career (Svolik, Reference Svolik2012: 178–82). The party's capacity to distribute important state positions, along with all the prerequisites that come with holding offices, gives party members a strong interest in the survival of the party (Geddes, Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018: 129–53). To the extent that elites with little in the way of partisan credentials can become the state president, cabinet members or regional governors, party strength is severely curtailed (Bader, Reference Bader2011: 190; Isaacs and Whitmore, Reference Isaacs and Whitmore2014: 705–6).

The second criterion is the party's control over the coercive apparatus. Whether the military and security sector can be relied on to repress the opposition can be a critical determinant of ruling party survival, especially during times of mass uprisings (Ndawana, Reference Ndawana2018; Kou, Reference Kou2000). The party's ability to control the armed forces varies considerably across authoritarian regimes. On one end of the continuum lie communist states wherein a Leninist party supervises and directs the functions of the armed forces (Huntington, Reference Huntington1995: 10). On the opposite end, ruling parties fail to establish any systematic mechanisms to control the military. The high degree of autonomy allows the military to play a key role in determining the regime's political trajectory.Footnote 1 Most party-based autocracies are somewhere in between the two extremes, with ruling parties attempting to interfere in the military's operation but falling short of imposing party structure on the military chain of command.Footnote 2

Conceptualizing party strength along two major dimensions generates four ideal types, as shown in Figure 1. On the top right corner are parties that feature high levels of institutionalization and dominance, as exemplified by the Frelimo in Mozambique. As a revolutionary party that led Mozambique's armed struggle toward independence, the party was organized as a Marxist-Leninist party with strong roots in the society. The Frelimo has experienced three leadership transitions since independence, thanks to its institutionalized procedures of succession (Carbone, Reference Carbone2005). The party's dominance over state institutions is also complete, even after the transition to multiparty elections in the 1990s (Manning, Reference Manning2010; Sumich, Reference Sumich2010). On the bottom left corner are parties that feature weak strength on both dimensions. As an example, the Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS) in Chad has a very narrow ethnic base and faces insurgencies from other ethnic groups. It survives mainly due to oil revenues and support from France. The party has never completed a leadership succession and revolves around President Idriss Déby. Although the MPS has moderate control over state positions, the Déby regime has confronted several coup attempts and large-scale defections from the army (Miles, Reference Miles1995; van Dijk, Reference van Dijk2007).

Figure 1 Two Dimensions of Party Strength

The left top corner represents parties that are highly institutionalized but unable to control other actors in the political system. An example is the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexico, which developed strong norms governing leadership succession and an impressive organization of voter mobilization (Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006). The PRI, however, was mainly responsible for conducting electoral campaigns and had little influence over decision making in the executive branch, which was controlled by the president (Langston, Reference Langston and Schedler2006: 65). The economic crisis in the 1980s further eroded PRI's control over economic resources as state-owned enterprises declined in number (Greene, Reference Greene2007). Finally, on the bottom right corner are parties that combine strong control over other political actors and weak institutionalization. The Cambodian People's Party (CPP) displays this combination. As Cambodia's ruling party since 1979, the CPP dominates government bureaucracies, the media and opposition parties. Civil servants are required to contribute their earnings to the party coffers for election campaigns (Un, Reference Un2005: 227). Most television stations are either owned or affiliated with the CPP, and opposition parties have been denied licences (Un, Reference Un2011: 552). At the same time, the party has not developed robust institutions to constrain its leader Hun Sen, who has subdued his rivals within the party to become the dominant figure in Cambodia. He has even built a bodyguard unit that is only answerable to him (Un, Reference Un2011: 553).

The Sources of Ruling Party Strength: A General Theory

In this section, we present a general theory of the sources of authoritarian ruling party strength and weakness. In brief, we argue that party strength stems from a strategic calculation that balances the benefits of building a strong party against its costs. Political actors are more likely to invest in party building when the benefits outweigh the costs. On the benefit side, party strength increases the likelihood of seizing and maintaining power by enhancing elite cohesion, building coalitions with diverse social groups and mobilizing mass support. On the cost side, party building is financially demanding: large amounts of revenue must be raised to recruit party activists and maintain local branches. Moreover, eliciting the support of various social forces expands the “winning coalition” for the autocrats, raising the prospect that they must share spoils with a broader segment of the population. While all political entrepreneurs confront this calculation, the benefits relative to the costs vary depending on the stage of the authoritarian life cycle and the particular strategic environment. Without loss of generality, the strategic environments fall into three scenarios: scenario 1 describes a group of political entrepreneurs that is in opposition and seeking to seize national power; scenario 2 describes a politician, supported by a small group of followers, who has come to power without the aid of a party; scenario 3 takes the perspective of a ruling party that has consolidated power. For the first two scenarios, we theorize the decision to form a political party, as well as the decision to build party strength. In what follows, we discuss how various factors specific to each scenario shape the cost-benefit analysis. We then derive hypotheses from the general theory that can be tested with empirical data.

Scenario 1: Opposition seeking to seize power

When a group of political entrepreneurs seeks to seize national power, the first decision it confronts is whether to form a political party. Since some kind of organization capable of solving collective action problems is necessary (Aldrich, Reference Aldrich1995), whether the group decides to form a party depends on the availability of alternative institutional vehicles. When such vehicles exist—for example, in the form of a clergy or religious organization—parties may be dispensed with (in Appendix I, we use the case of the Taliban in Afghanistan to illustrate this point). Otherwise, forming a political party is likely the preferred option. Once a party is formed, the power-seekers face a strategic calculation about whether to build a strong party. We argue that there are three factors that determine the benefits of party building relative to its costs.Footnote 3

The first factor is whether the current regime allows for multiparty elections through which an opposition party can come to power. If such a legal path to power exists, the benefits of building a full-blown authoritarian party dwindle compared to its costs. In this case, the power-seekers must build linkages to citizens and deliver their votes, but it is not necessary to establish an alternative governance structure and coercive apparatus. In other words, party building can focus on the institutionalization dimension and ignore the dominance dimension. However, if the power-seekers face a repressive environment that eliminates the possibility of peaceful turnover, their goal must be a violent overthrow of the incumbent regime. Here, the relative benefits of a more comprehensive party-building project increase. In addition to creating institutions that ensure elite cooperation and popular support, the power-seekers need to build armed forces to fight the state and an administrative structure that governs territories under their control. To coordinate anti-regime activities, the rebels typically seek to achieve a fusion of party, military and bureaucracy by appointing partisan cadres to lead all three institutions. After achieving power, the rebel forces and administrative units will become the national army and state bureaucracy, respectively. Then, the ruling party is well positioned to maintain dominance over the military and civil bureaucracy due to relationships forged during armed insurgency.

In the case of an opposition aiming to overthrow the incumbent regime, a second factor that determines the relative benefits of party building is the strength of the current regime. If the regime is highly personalist, corrupt and/or narrowly based, it is relatively easy for the opposition to mobilize broad segments of the population against the rulers. Therefore, it is cost effective for the power-seekers to achieve a degree of party strength that is just sufficient to seize power. For example, the Somoza dynasty that ruled Nicaragua until 1979 alienated so many social groups that organizing a few labour strikes and urban terrorist attacks were enough to bring the Sandinistas to power. By the time the FSLN troops entered Managua, the strength of the revolutionary party was still hampered by severe internal divisions and the existence of competing power centres such as the Catholic Church and the bourgeoisie (Parsa, Reference Parsa2000: 255–62; Foran and Goodwin, Reference Foran and Goodwin1993).

By contrast, if the power-seekers face a better organized and more broadly based regime, more intensive party-building efforts will be required that eventually lead to more strength on both the institutionalization and dominance dimensions. On the one hand, to confront a resourceful regime, the party must enhance internal discipline and cohesion, articulate a sophisticated ideology and build party branches that penetrate different social sectors (Tucker, Reference Tucker1961; Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018: 40). All these undertakings give rise to a more institutionalized party. On the other hand, the party must also tighten its grip over the armed forces and auxiliary organizations such as trade unions and student groups. Due to the resilient nature of the incumbent, most government troops and bureaucrats will not simply defect to the rebels. Instead, they must be defeated before the rebels can seize power. As a result, most of the newly founded regime's personnel will be drawn from the rebels rather than from functionaries of the ancien régime. This dynamic also tends to strengthen the ruling party's control over the administrative and coercive apparatuses. In Appendix I, we use the Frelimo case to illustrate this point.

The third factor has to do with the presence of resources that can substitute for party strength to improve the prospect of power seizure. Such resources typically come in the form of military and economic aid provided by foreign powers sympathetic to the insurgents’ cause, but they may also accrue from natural resources in rebel-controlled areas. Historically, almost all successful revolutions received some amount of foreign support. However, if a seizure group has very easy access to externally provided funds, arms or even personnel, robust party institutions are less likely to emerge. External support often causes rifts within the insurgency between those who depend on such support and leaders who emphasize the local nature of the struggle. It also reduces the need to build grassroots organizations to garner mass support. Parties dependent on foreign aid will also evolve in a less dominant direction, since it is no longer necessary to incorporate diverse social and ethnic groups into a lasting party-dominated coalition (Smith, Reference Smith2005). In Angola, the anti-Portuguese independence struggle was led by three major insurgent parties. Although the inter-movement rivalries originated from pre-existing ethnic and regional divides, the fact that each party received support from different foreign patrons further precluded the formation of a united front. As post-independence Angola slipped into civil war, scholars pointed out that “when analyzing international intervention and Cold War strategic interests one has to wonder whether the civil war would have taken place if the liberation movements had not been heavily armed in support of interests other than Angolan national ones” (Leao and Rupiya, Reference Leao, Rupiya and Rupiya2005: 13). By contrast, if the insurgents face a hostile international environment wherein foreign support mainly flows to the incumbent regime, they will have more incentives to rely on party building to sustain the movement.

Scenario 2: Sitting dictators that seized power without a party

In this scenario, a politician supported by a small circle of followers has come to power without the aid of a party. Once in power, the sitting dictator faces a critical decision about whether to form a support party. There are three major considerations that will weigh heavily in this initial decision. First, the dictator may want to legitimize their rule by winning elections, and political parties are the most natural instruments to organize an electoral campaign. By winning elections as the leader of a party, the dictator can portray the ruling elites as motivated by political ideals rather than greed. Second, a ruling party can be used to counterbalance the power of the military. The ability of party workers to mobilize mass demonstrations and overwhelming votes in support of the incumbent ruler might deter the armed forces from plotting a coup d’état (Geddes, Reference Zeng2005). Third, a ruling party may be used as an institutionalized platform through which the dictator can bargain with and elicit cooperation from other powerful elites (Reuter and Remington, Reference Reuter and Remington2009; Reuter, Reference Reuter2017). Having such a party may help the dictator get policy initiatives passed in the legislature and implemented by regional elites. Thus, to the extent that the dictator needs legitimacy, a coup-proofing strategy and the cooperation of other elites, the dictator is more likely to establish a new party.

Even if the sitting dictator decides to form a party, there are two distinct reasons why they may be reluctant to build a strong party. First, unlike an opposition movement, the dictator does not need a dominant party to take on the daunting task of seizing power. To stay in power, the ruling party can funnel money from public budgets to party coffers and transform public agencies into campaign tools (Greene, Reference Greene2007, Reference Greene2010). The dictator's personal control over public resources serves as an efficient substitute for the hard work of building an organized network that penetrates both the state and society (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988: 69). Second, since the dictator's primary aim for creating the party is to consolidate personal rule, they would be particularly sensitive to paying the cost of expanding the ruling coalition. If the party becomes institutionalized, the dictator's personal power will be diluted and they will need to share regime spoils with a larger set of supporters. Fearing this development, the dictator's instinct is to block any institutionalization process that gives rise to an autonomous centre of power (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988: 67). In Appendix I, we use the cases of the APRC in Gambia and the United Russia Party to illustrate how the calculations of incumbent dictators led to less institutionalized and dominant parties.

Scenario 3: Ruling parties seeking to stay in power

Regardless of the route to power, all authoritarian ruling parties face a number of common factors that affect their cost-benefit analysis in terms of whether to engage in party building. These factors include the strength of organized opposition to the regime, the availability of natural resources and the presence of international pressure. When well-organized opposition groups pose a threat to the party's grip on power, they incentivize the ruling party to enhance its organizational strength to forestall anti-regime mobilization. A series of pre-emptive measures—including the expansion of grassroots organizations to mobilize and monitor the citizens, emphasis on military leaders’ loyalty to the ruling party and the reinforcing of party discipline and cohesion—are available to ruling autocrats who want to match opposition threats with a more vital ruling party.

Building up party strength is clearly not the only option when autocrats face opposition challenges. One obvious alternative is to enhance state repression—restricting civil liberties and/or physically eliminating dissidents. Repression, however, is a highly visible form of socio-political control that imposes high legitimacy costs on rulers (Davenport, Reference Davenport2007). An institutionalized party expands the regime's support base and incorporates more actors into decision making. Through a combination of indoctrination, mobilization and co-optation, strong parties significantly reduce the legitimacy losses associated with repression and bolster the prospects of regime survival. To the extent that autocracies have a long time horizon beyond the duration of any single leader, party building should be an attractive option. Meanwhile, the choice between repression and party building also rests on access to coercive resources, discussed below.

A regime's access to natural resource wealth reduces the relative benefits of party building. Instead of utilizing a party to mobilize mass support and dominate other institutions, it may simply use mineral revenues to buy the support or acquiescence of powerful social groups (Gandhi and Przeworski, Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007: 1285; Ross, Reference Ross2001: 332; Smith, Reference Smith2005: 431). In rentier states, “large sums of money are spent on sustaining patronage networks and/or providing huge subsidies to the population to garner social and political support, rather than on developing institutionalized mechanisms of responsiveness” (Weinthal and Jones Luong, Reference Weinthal and Luong2006: 38). In addition to relieving social pressure, rents make repression a more viable option in dealing with opposition. Resource wealth allows autocrats to spend more on the military and internal security—instruments that are critical for authoritarian survival (Albertus and Menaldo, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2012; Bellin, Reference Bellin2004). Easy access to coercive resources will further reduce attention paid to the more subtle work of building a party to infiltrate other institutions and win grassroots support.

The effects of international pressure on a ruling party's calculation are more complicated. Here, international pressure mainly refers to the efforts by Western states and international organizations to induce a one-party regime to pursue liberation and allow meaningful political competition. We contend that high international pressure negatively affects party strength along the dominance dimension but tends to bolster it along the institutionalization dimension. Recent studies have suggested that close ties to Western states create pressure for autocracies to conform to democratic norms (Boix, Reference Boix2011; Gleditsch and Ward, Reference Gleditsch and Ward2006; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2005; Manger and Pickup, Reference Manger and Pickup2014; Pevehouse, Reference Pevehouse2005; Ulfelder, Reference Ulfelder2005). For autocratic ruling parties, the cost of maintaining dominance in the political system grows higher when external actors are demanding compliance with democratic principles, which requires a clear separation between party and state. Practices such as making party membership a precondition for serving in public office and inserting party cells into the military hierarchy are repugnant to promoters of democracy. To the extent that autocracies depend on Western democracies for legitimacy and material support, they would be under pressure to curtail the party's reach into state institutions. Meanwhile, international pressure may incentivize authoritarian parties to become more institutionalized. As the international community provides support for domestic opposition groups, the importance of party building for regime resilience will receive more attention from autocrats. Importantly, building more impersonal, cohesive and mass-based party institutions does not violate democratic norms and is unlikely to attract international criticism. If anything, pro-democracy groups may welcome these moves, as they see institutionalized political parties as important for democratic consolidation.

Based on the general theory, we now derive several testable propositions to set up the empirical analysis.

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian parties that came to power through revolutionary struggles tend to develop greater party strength during their life span than other parties.

Hypothesis 2: Authoritarian parties created by sitting dictators tend to develop less party strength during their life span than other parties.

Hypothesis 3: The amount of natural resource wealth available to a regime is negatively associated with ruling party strength.

Hypothesis 4: The amount of external democratizing pressure faced by a regime is negatively associated with the dominance dimension of party strength.

Hypothesis 5: The amount of external democratizing pressure faced by a regime is positively associated with the institutionalization dimension of party strength.

While these hypotheses are firmly grounded in the theoretical model, three additional clarifications should be made. First, in this study, revolutions are defined as sustained, violent struggles that seek to overthrow the current regime and transform existing social order.Footnote 4 As suggested in our model, the need to forcefully oust an incumbent regime increases the benefits of party strength. Following Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1979) and Levitsky and Way (Reference Zeng2013), our definition of revolution emphasizes the ideational nature of the struggle because, compared with insurgencies motivated primarily by material benefits, those that aim to transform social structures tend to confront more determined opposition, which further necessitates strong parties.

Second, not all testable hypotheses that can be derived from the theory are listed here. For example, the analysis of scenario 1 implies that armed groups that have more access to rents will develop weaker parties, and that of scenario 3 implies that regimes that face more powerful opposition will develop stronger parties. Due to space limits and data availability issues, we leave the testing of these propositions to future studies. In Appendix II, we use existing data to test several additional implications of the theory. These include the hypothesis that the existence of multiparty elections reduces the opposition's incentive to build strong parties (scenario 1), that parties created to overtake weak regimes tend to be weaker (scenario 1) and that dictators who seize power are more likely to create a new party if they intend to gain legitimacy by winning elections (scenario 2). All three hypotheses receive moderate or strong support from our empirical models.

Third, while the theory emphasizes the explanatory power of how parties came to power, we recognize that the origins of authoritarian parties are not exogeneous. It is possible that some structural conditions (for example, inequality, social discontent, repression) make revolutions more likely and cause the insurgents to be more organized. This raises the question whether the observed correlation between party origins and party strength is spurious. In response, we argue that the structural factors, if they exist, must work through the revolutionary process to give birth to strong parties. The hard work of recruiting militants, educating and serving the masses and fighting guerrilla warfare is critical for the emergence of strong parties. Thus, the causal power of revolution should be stressed, although it may serve as a mediator variable between structural conditions and party strength.

Data and Method

The sample used in this study comes from the Autocratic Ruling Parties Dataset (ARPD) developed by Michael Miller (Reference Miller2020), which includes all autocratic ruling parties that were in power between 1940 and 2015. Autocracy is defined using Boix et al.'s (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013) binary measure, and ruling party is defined as a political party that is either the supreme ruling power or is used as a significant vehicle of power by the regime and is clearly pre-eminent among all parties. For the purpose of this study, a major advantage of the ARPD is its inclusion of all regimes that rely meaningfully on a support party, generating a sample that is larger in scope than the party-based regimes wherein the ruling party is the primary institution that held power (see the Autocratic Regime Dataset, Geddes et al., Reference Zeng2014). Restricting the sample to party-based regimes risks selection bias by studying only regimes with relatively strong parties. Therefore, using the APRD is more likely to produce unbiased inferences by maximizing variation on the dependent variable.

The APRD is in country-year format and tracks continuous party spells in power. The dataset includes variables that describe key features of regimes and ruling parties. One country may have multiple ruling party spells, and more rarely, one party may have multiple spells in power. In total, the sample includes 279 ruling party spells across 262 distinct parties and 133 countries.

Dependent variables

The outcome to be explained by this analysis is authoritarian party strength, which we have argued can be measured with a number of observable indicators. Based on the theoretical discussion, five variables are employed to measure party strength. Data on these variables are taken from two sources: the Authoritarian Regime Data Set collected by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (the GWF dataset)Footnote 5 and the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) project (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Steven Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Knutsen, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Staton, Zimmerman, Sigman, Andersson, Mechkova and Miri2016, Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Steven Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Krusell, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Pernes, von Römer, Stepanova, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019). The V-DEM project provides indicators on different features of political parties, which are based on coding by thousands of country experts. Below we provide a brief account of how these variables are constructed, while a more detailed explanation can be found in Appendix III.

The first variable, de-personalization, is a time-varying latent variable that draws upon various regime features to indicate the degree to which “a dictator has personal discretion and control over the key levers of power in his political system” (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018: 70). Examples of these features include whether access to high office depends on personal loyalty to the regime leader and whether the party executive committee is absent or simply a rubber stamp of the leader's decision. GWF used a logistic item-response theory (IRT) model to synthesize these features and construct the measure personalism.Footnote 6 We transform the original variable into an index called de-personalization ranging from 0 to 1, with higher levels of personalism approaching 0 and lower levels of personalism approaching 1.

The second variable measures party control over the state administration. Control cabinet captures the proportion of cabinet positions occupied by members of the ruling party. It is reasonable to assume that higher values of control cabinet indicate greater party control over the recruitment of elites into the executive branch. Control cabinet is an ordinal variable ranging from 0 to 3.

The third variable shows how firmly the party controls the military. Control military is an ordinal variable that corresponds to five levels of party control, with higher values indicating greater control.

The fourth and fifth variables are designed to reflect party cohesion. Party switching measures the percentage of the members of the national legislature that changes or abandons their party in between elections. We transform the variable so that higher values indicate lower percentages of party switching (greater cohesion). Legislative cohesion indicates how often party members vote as a coherent bloc on important bills. High levels of cohesion suggest that members tend to vote with their parties, and vice versa.

Table 1 displays the correlation matrix for the five dependent variables. A few observations can be made regarding how the variables are related to the latent variable, party strength. First, all correlation coefficients are positive, lending credibility to the claim that the five variables are indicators of an abstract concept. Second, none of the coefficients is greater than 0.4, suggesting that the indicators indeed capture different aspects of party strength. Third, the correlation between de-personalization and cohesion indicators are very weak. This implies that the institutionalization dimension itself consists of two subdimensions. The finding supports Slater's (Reference Slater2003) argument that authoritarian parties can be highly unified, disciplined and effective as an organization but very personalized at the top.

Table 1 Correlation Matrix for Five Indicators of Party Strength

Independent variables

There are four independent variables that explain party strength. The first two are time-invariant variables that capture how authoritarian ruling parties gained power. Revolution is a binary variable that equals 1 for cases where the ruling party came to power through sustained, violent struggles that sought to transform existing social order. Drawing on studies of revolutions and revolutionary regimes (Goldstone, Reference Goldstone2015; Goodwin and Skocpol, Reference Goodwin and Skocpol1989; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2013), we coded 19 cases as belonging to this category. Likewise, post-seizure creation is a binary variable that equals 1 if the ARPD codes a party's pathway to power as “a new party imposed by a sitting dictator” or “the military leadership.” In these cases, dictators created ruling parties after they seized power without the aid of a party.Footnote 7 Appendix V provides description of selected cases to illustrate why they were coded as ruling parties originating from revolutions or post-seizure creation. In the case of revolution, we also provide the full list of cases and examples to explain why some cases do not qualify.

The third independent variable, resource, measures a regime's access to natural resource wealth, which is operationalized as the sum of oil and gas production as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) (Ross, Reference Ross2013). The fourth variable, regional democracy, aims to measure the amount of external democratizing pressure faced by a regime. We use the share of democratic regimes in a region as a proxy for such external pressure. This decision was informed by recent findings that higher shares of regional democracies translate into pressure to democratize (Brinks and Coppedge, Reference Brinks and Coppedge2006; Gleditsch and Ward, Reference Gleditsch and Ward2006). In robustness tests, we also use two alternative proxies for international pressure: the share of international governmental organization (IGO) co-members that are democratic and the share of military allies that are democratic.Footnote 8 Both measures capture a regime's dependence on external democracies, which may translate into democratizing pressure.

The variables reflecting party origins are not entirely exogenous, since the factors that led dominant-party regimes to emerge in a certain way might also affect subsequent party strength. Such structural conditions will be controlled for in the analysis. On the other hand, external pressure is mostly a reflection of the international environment over which autocrats have limited control. Availability of natural resources is also a given attribute that state leaders cannot easily manipulate. Endogeneity should not be a serious concern for the pressure and rents variables.

Control variables

To draw valid statistical inference, the empirical analysis must account for alternative explanations of ruling party strength. First, the study controls for a country's basic background conditions such as levels of economic development and demographic features. Four variables fall into this category: GDP per capita, GDP growth rate (growth), ethnic fragmentation, and population size. Second, party strength may simply be a function of party age. The longer a party has existed as an organization, the more actors will develop expectation of stability and invest in the skills necessary for institutional reproduction (Levitsky and Murillo, Reference Levitsky and Murillo2009: 123). We therefore control for the number of years a party has been in existence. Third, we control for oil price (in dollars per barrel) as an indicator of international economic environment. Finally, the end of the Cold War represents a fundamental change in the geopolitical environment. We use a dummy variable to control for the effects of this event. Table 2 shows summary statistics for the main variables.

Table 2 Summary Statistics for Main Variables

a In 155 country-year observations (5.1%), the total dollar value of oil and gas production exceeds national GDP. The Ross (Reference Ross2013) dataset codebook does not explain why this is so. We believe that this is because some of the oil and gas production in a country is carried out by foreign companies and sold in the international market. These goods therefore do not go through the domestic economy and were not counted as part of GDP

Results

We test our hypotheses using data from all autocratic ruling parties that were in power between 1940 and 2015. A problem inherent in analyzing panel datasets is the existence of unmeasured factors associated with each cross-sectional unit. To address this issue, we use random effects models that assume that the unit effect follows a specific probability distribution. This approach allow us to include time-invariant variables of substantive interest such as the genetic models of authoritarian parties. The second and third dependent variables (control cabinet, control military) are ordinal, which necessitates the use of ordinal logistic regression. All covariates are lagged by one year to reduce concerns of reverse causality. Robust standard errors are clustered by country to correct for panel-specific autocorrelation.

Table 3 shows the main results. Because the variables revolution and post-seizure creation are put in the same model, the reference group includes those regimes wherein the ruling party gained power through neither revolution nor post-seizure formation.Footnote 9 With regard to hypothesis 1, the results show that compared to other ruling parties, revolutionary parties exert stronger control over the cabinet and military. Converting the log-odds coefficient into proportional odds ratio, revolutionary parties are 3.28 times more likely to obtain a particular degree of cabinet control rather than lower levels of control (p < .10). The same statistic for military control is 7.8 (p < .01). As argued above, revolutionaries often need to build their own administrative and military structures before coming to power. Party dominance over these structures apparently persist in the post-revolutionary era. However, after controlling for other variables, there is no evidence that revolutionary parties are stronger on the institutionalization dimension. Hypothesis 2 is also supported by the analysis, as parties formed by sitting dictators tend to be more personalized and exert weaker control over the political system. Post-seizure creation is associated with a 0.17 decline in de-personalization (p < .01), a strong effect for an index that ranges from 0 to 1.

Table 3 Explaining Party Strength in Authoritarian Regimes

Note: The dependent variables are indicators of party strength. Entries in models (1), (4) and (5) are OLS coefficients. Entries in models (2) and (3) are ordered logit coefficients with t-statistics in parentheses. Standard errors are clustered by country.

* p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01

The corrosive effects of resource rents on party strength are fully demonstrated. The variable has a negative and statistically significant effect on all indicators of party strength, with the exception of control military. As an example, changing the resource variable from the minimum to maximum value is predicted to increase the number of legislative members who switch their party in between elections by 39 percentage points. The analysis also supports hypotheses related to the impact of international pressure. On the one hand, democratizing pressure significantly weakens ruling parties’ control over the cabinet and military (p < .01), corroborating hypothesis 4. On the other hand, consistent with hypothesis 5, higher shares of regional democracy tend to make ruling parties less personalized (p < .01).

Turning to the control variables, there is strong evidence that ruling parties grow stronger as they get older, as we expected. Importantly, controlling for party age shows that the substantial difference in strength between ruling parties with different pathways to power is not an artifact of how long these parties have existed. Another notable result is that average authoritarian party strength has declined in the post–Cold War period. Among other things, this finding may be due to the existential threats faced by many regimes during the Cold War in the form of foreign-supported insurgencies (for example, the Contras in Nicaragua, Renamo in Mozambique, the communists in Malaysia). Consistent with our theoretical argument, well-organized opposition tends to push ruling parties to be more coherent and disciplined to match anti-regime threats.

Finally, population size is found to aggravate party switching and, to a lesser degree, personalization. While the relationship between polity size and party strength warrants a separate study, here we offer some tentative thoughts on the finding. Large countries tend to contain more social groups divided along religious, ethnic and class cleavages, which provides more bases for organized political groups. Thus, elites in large polities may have more exit options, which explains the higher rate of party switching. Meanwhile, a populous and heterogeneous society lends weight to the rhetoric that a “strong and steady hand” is necessary to hold a diverse country together. Partly due to regime propaganda and partly out of self-interest, members of large communities may be more willing to accept a personalist dictator in exchange for political order. This finding contradicts the argument of Gerring and Knutsen (Reference Gerring and Knutsen2019), although their study focusses on institutionalized succession rather than personalism per se.

In Appendix IV, we perform a number of additional tests to show that the main results are not sensitive to alternative measurement of key variables, model specifications and estimation methods. The first test reruns the analysis with country fixed effects. The second test uses two alternative proxies for international pressure: the share of IGO co-members that are democratic and the share of military allies that are democratic. The third examines if dependence on foreign aid has similar negative effects on party strength as resource rents.

Third, considering the slow-moving nature of the dependent variables, using country-year observation might require difficult assumptions about the time needed for independent variables to show their effects. To address this concern, we conduct a cross-sectional analysis, using average values of party strength over a regime's lifetime as the outcome. The independent variables are averaged accordingly. Moreover, we perform analyses to examine how revolution and post-seizure creation affect party strength at the 5th, 10th and 15th year in a regime's lifespan. An important result is that revolutionary origins strongly determine whether a ruling party can last for more than 15 years, but among those parties that do pass the 15th-year mark, revolutionary origins do not make much difference in terms of party strength. Put differently, the main benefits of revolution on party strength are realized in the first 15 years of a regime's lifespan.

Fourth, we examine the legacy of other pathways to power in addition to revolution and post-seizure creation. We focus on three such pathways: election (party wins an election, possibly uncompetitive), coup (party leads a coup) and foreign imposition (party installed by a foreign power).Footnote 10 Among other things, we find that ruling parties imposed by foreign powers have significantly greater control over the cabinet and military. The explanation for this pattern is simple: the vast majority of these cases (451 country-year observations out of 482) were communist parties imposed by the Soviet Union. They adopted the model of a Leninist vanguard party that asserted total control over state institutions. This result demonstrates the importance of the Marxist-Leninist ideology on party strength.

Fifth, one may wonder whether the positive impact of revolution on party strength is an artifact of revolutionary parties being mostly communist. This is not the case. Among the 24 ruling parties coded by the ARPD as communist (organized as communist with international involvement from the Communist International), only 8 came to power through revolutionary struggles. Indeed, if we focus on the subsample of communist parties and rerun the main analysis, revolution is still positively associated with control cabinet, control military and legislative cohesion. Thus, revolution positively affects party strength independent of the communist origins of these parties.

Conclusion

Existing studies have spent a great deal of ink and time exploring the role of parties and legislatures in bolstering authoritarian survival, but none has elaborated a general theory of the sources of ruling party strength, let alone systematically tested it. This article takes a step in this direction by presenting a unifying framework that centres on the political actors’ calculation that balances the costs and benefits of building a strong party. It argues that the relative benefits of strong parties depend on the stage of the authoritarian life cycle and factors specific to the strategic environment. The observable implications of the theory are supported by empirical analysis. Parties that originated from revolutions tend to be the strongest, whereas those created to support an incumbent dictator face the greatest obstacles to developing party strength. A country's resource endowments and external environment also shape the dynamics for party building.

This article raises important questions that should be addressed in future studies. First, the study has primarily focussed on the effects of individual factors, but we recognize that these factors can interact to influence party development. For example, while it is predicted that the presence of formidable opposition can incentivize the formation of strong parties, the degree to which autocrats will resort to the party-building option may depend on other variables, including the availability of resource wealth. Similarly, while revolutions tend to leave behind strong parties, whether party strength can persist may depend on the challenges from domestic and international groups. Detailed case studies can therefore make substantial contributions to illustrating the interactive effects of various factors.

Second, we argue that the implications of a strong authoritarian party for democratization remain an understudied area. Existing works have seldom noticed that the two dimensions of party strength can have different consequences for democratizing prospects. On the one hand, institutionalization has a ruling party increasingly resemble a typical Western political party, characterized by impersonality, internal coherence and stable roots in society. While these features may contribute to authoritarian control, in the long run they could also give the ruling party the “strength to concede” by instilling the belief that it could thrive under a democratic system (Slater and Wong, Reference Slater and Wong2013). On the other hand, dominance requires the ruling party to evolve in a Leninist direction with tight control over state organs and the civil society. As such, it is difficult to view it as anything other than an outright obstacle to democracy. Distinguishing between the two dimensions will serve as an important starting point for future analyses of party-based autocracies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000839

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dan Slater, Lucan Way, Dwayne Woods, Xiao Ma, Peng Hu, Yu Zheng, Zhongyuan Wang, Vera Zuo, Xun Cao, Gangsheng Bao and three anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on previous drafts. The Shanghai-based Wujiaochang academic community also provided intellectual support for this research.