Introductory Remarks Catherine J. Frieman

Over the (slightly more than) two decades that the European Journal of Archaeology (formerly the Journal of European Archaeology) has been in print, we have published a number of excellent and high profile articles. Among these, Paul Treherne's seminal meditation on Bronze Age male identity and warriorhood stands out as both the highest cited and the most regularly downloaded paper in our archive. Speaking informally with friends and colleagues who work on Bronze Age topics as diverse as ceramics, metalwork, landscape phenomenology, and settlement structure, I found that this paper holds a special place in their hearts. Certainly, it is a staple of seminar reading lists and, in my experience at least, is prone to provoke heated discussions among students on topics as far ranging as gender identity in the past and present, theoretically informed methods for material culture studies, and the validity of using Classical texts for understanding prehistoric worlds. Moreover, in its themes of violence, embodiment, materiality, and the fluidity or ephemeral nature of gendered identities, it remains a crucial foundational text for major debates raging in European prehistoric archaeology in the present day.

Thus, it seemed pertinent that, as part of the commemoration of our 20th volume, we should return to our most loved paper to ask why and how it has aged so well, in what ways the debates we are currently having build on its themes, and where new data or interpretations have since enhanced (or challenged) Treherne's compelling narrative. The following short articles were solicited as responses to and reflections on Treherne's original article. Authors were asked simply to build on Treherne's work and to reflect on how it had impacted their own research and their wider field. These reflections range from reviews of the ongoing significance of Treherne's ideas to our understanding of gendered identities in the Bronze Age (Brück, Rebay-Salisbury, Bergerbrant), to the political impact of prehistoric research into gender identity and masculinity (Montón Subiás, Sofaer), and to the identification and social position of war, warfare, warrior's bodies, and depictions of warriorhood in prehistoric societies (Knüsel, Vandkilde, Giles). We are also pleased to include a short response by Paul Treherne, now chair of history at St Stephen's International School in Rome, to these reviews and to the ongoing significance of his postgraduate research for European prehistoric archaeology.

Gender and Personhood in the European Bronze Age Joanna Brück

Paul Treherne's article in the Journal of European Archaeology for Reference Treherne1995 is one of the most influential pieces of work on the Bronze Age written in the past few decades. It effectively critiqued previous work on prestige goods—arguing, for example, that we need to account for the particular character of the grave goods that accompany high status burials—but it also sustained and crystallized existing models of a Bronze Age warrior elite.

The image of the Bronze Age warrior is extraordinarily enduring; but it is, in my opinion, highly problematic, for it dominates our narratives of the period to the virtual exclusion of alternative interpretative frameworks, and it runs the risk of missing much of the depth, texture, and complexity of Bronze Age life. The following comments are based on many years of work on the British Bronze Age, but are relevant, I believe, for other areas of Europe too. It is true, of course, that burials accompanied by swords and other weaponry are a feature of many regions, but there are other sorts of grave groups that provide equally interesting, and often rather different, insights into Bronze Age society. In particular, there is a danger that, by focusing on warrior burials and accoutrements, we may inadvertently construct an androcentric vision of the period: in common with Treherne, recent work on the role of warriors and warfare in the Bronze Age (e.g. Kristiansen & Larsson, Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005; Harding, Reference Harding2007) assumes that positions of social, political, and economic power were held solely by men, and that women were (like fine weaponry) the objects of elite exchange rather than social agents in their own right. There is, of course, copious evidence to counter such assumptions. ‘Wealthy’ female burials are found in many regions: the cremation burial of an adult female from the Early Bronze Age cemetery at Barrow Hills, Oxfordshire, was accompanied by a bronze awl, knife-dagger, and necklace of amber, faience, and jet/shale (Barclay & Halpin, Reference Barclay and Halpin1999: 162–65), while the adult female from the famous barrow of Borum Eshøj on Jutland was buried with a dagger, a fibula, an elaborately-decorated belt disc, a neck-ring, two arm rings, two spiral finger rings, and two small bronze tutuli, among other things (Glob, Reference Glob1973: 43–45). Our tendency to sideline this evidence, or to interpret it as an indication that women acted as ‘vehicles for the display of their husband's resources’ (Shennan, Reference Shennan1975: 286), is primarily a reflection of the position of women in our own recent past and can be critiqued on theoretical grounds: post-Enlightenment understandings of the self construct men as active subjects and women as passive objects, but this is part of an ideology that served particular purposes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, facilitating the colonial endeavour, for example, by feminizing and commodifying landscape.

Treherne argues that Bronze Age mortuary practices worked to construct an image of bodily perfection for the individual—the warrior's beauty, as he puts it. Yet, this emphasis on the individual, and the assumption that the integrity of the body was a key concern during this period, are problematic, for they impose onto the past a model of the self that is particular to the contemporary western world. Body image is a matter of enormous concern in Euro-American society today, and the ideological primacy of the individual means that the body and the self are viewed as coterminous, one mapping neatly onto the other, and both having well-defined and impermeable boundaries. There is much to suggest, however, that Bronze Age concepts of the person were very different. Mortuary practices in Britain often involve the deliberate fragmentation of the body. This is true even for those funerary traditions most commonly invoked as evidence for an increasing concern with the ‘individual’, for example Beaker burials of the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age. The grave of the ‘Boscombe bowmen’, for example, contained the incomplete remains of several adults and children (McKinley, Reference McKinley and Fitzpatrick2011: 28–31): the articulated adult male (burial 25004) was missing his left hand and forearm, while the two bundles of disarticulated bone found just above and below this burial comprise selected skeletal elements from five other individuals, predominantly skull and longbone fragments from the left side of the body. Cremation burials are characteristic of the Later Bronze Age in the same region, and the majority of these comprise only a portion of the remains of the deceased. The three heaviest of the twenty-one urned adult cremation burials found at Coneygre Farm in Nottinghamshire weighed 1475 g, 915 g, and 735 g respectively, but the remaining eighteen burials weighed less than 600 g, and fourteen of these were under 400 g (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Harman and Wheeler1987: table 1). The evidence for the deliberate destruction of grave goods (Brück, Reference Brück2004, Reference Brück2006) and the circulation of heirlooms (themselves often incomplete or composite objects: Sheridan & Davis, Reference Sheridan and Davis2002; Woodward, Reference Woodward2002) indicates that objects were subject to practices of fragmentation and curation, and we can suggest that human bodies may have been treated in similar ways: the resulting elements were exchanged over space and time to mark, mediate, and transform inter-personal relationships. Such practices hint at relational or dividual concepts of the self very different from modern Western ideologies of the individual (see Strathern, Reference Strathern1988; Busby, Reference Busby1997).

An interest in ancestral ‘relics’ perhaps explains the evidence for the reopening of burials and for the reordering of the bones encountered when graves were reused. The Early Bronze Age shaft grave at South Dumpton Down in Kent contained a sequence of burials (Perkins, Reference Perkinsnd); each time a body was placed in the grave, the skull of the previous interment was removed. Evidence for the reopening of graves on the Continent has often been interpreted as ‘grave robbing’, but could equally have acted as a means of acquiring the bodily remains or objects associated with known and important deceased members of the community. The Middle Bronze Age cremation graves at Pitten, in Austria, were provided with special ‘doorway’ structures that allowed mourners to access the grave: it has been suggested that their purpose was to allow food offerings to be given to the deceased over a protracted period of time (Sørensen & Rebay-Salisbury, Reference Sørensen and Rebay-Salisbury2005: 166–67), but they may also have allowed grave goods or quantities of cremated bone to be removed. Certainly, cremation burials in Continental Europe sometimes contain only portions of the bodies of the deceased: the urn from grave 11 in area 1 of the Late Bronze Age cemetery at Niederkaina in eastern Saxony, for example, contained just 427 g of burnt bone belonging to an adult (Coblenz & Nebelsick, Reference Coblenz and Nebelsick1997: 40). Because my own research specialism is the British Bronze Age, I do not have a clear sense of how prevalent such practices were on the Continent, although this is certainly a question that would be worth exploring. In Britain, the deliberate deposition of fragments of human bone in domestic contexts (for example, in pits or postholes at the entrance to settlements: Brück, Reference Brück1995) provides some insight into the ‘afterlives’ of such relics. Usually, such finds comprise single fragments of skull or longbone, although the complete mummified ‘body’ of an adult male buried under the floor of roundhouse 1370 at Cladh Hallan in Scotland was composed of the skull and cervical vertebrae from one individual, the mandible of a second, and the postcranial bones of a third (Parker Pearson et al., Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain and Craig2005), all several centuries old on burial, suggesting a protracted and complex phase of post-mortem manipulation. Together, what such practices indicate is that the identity of the deceased was not considered fixed on burial but could in fact be reworked as and when fragments of bodies and associated objects were removed, exchanged, inherited, and (re)combined in a variety of mortuary and non-mortuary contexts. Treherne's argument that there was a finality to the moment of burial resulting in the creation of a fixed image of the deceased can therefore be called into question: instead, memory was created through practices that involved the reworking and recontextualization of fragments of the dead.

In addition, it is of course problematic to assume that grave goods were owned by the deceased and reference intrinsic personal attributes (Brück, Reference Brück2004). Grave goods may not have functioned as objects of display, but may instead have described aspects of the relationship between the living and the dead, or ideas about death and the afterlife. Although it is often assumed that cremation burials accompanied by razors must be male, in fact such items may be the product of ritual practices enacted as part of the funerary rite. Toilet articles such as razors, tweezers, and awls may have been used to mark the bodies of the mourners, for example by shaving the hair (Woodward, Reference Woodward2000: 115). This would have helped to distinguish different phases of the mortuary rite, particularly periods of separation or liminality. Objects such as wagons reference connectivity, travel, and transformation, while drinking cups are as much about commensality and the consumption of substances that facilitated communication with the otherworld, as personal status. Across much of western Europe, swords are found not in burials but were instead deposited in rivers (e.g. Fontijn, Reference Fontijn2002), sometimes complete and still usable, and sometimes deliberately decommissioned—bent and broken in ways that cannot simply be explained as a product of combat damage. Often, large numbers of swords and other bladed weapons are found at particular locations, for example fording places or the confluences of rivers. Such finds hint at the fluidity of personal identity for they suggest that the role of the warrior may have related only to a particular phase in the lifecourse, or may have been a temporary and highly ritualized form of identity that was taken up in particular political contexts and subsequently relinquished (Fontijn, Reference Fontijn and Parker Pearson2005). The deposition of quantities of metalwork in rivers and their separation from the bodies of particular individuals hints at collective or community identities tied to place, with the character of the objects (weapons made of metal) referencing the dangerous and transformative properties of social and political boundaries. Yet, the relative paucity of defended settlements in these regions suggests that other concerns occupied those same ‘warriors’ for much of their daily lives.

There is, therefore, much to suggest that Bronze Age models of the self were very different from those common in our own cultural context. If we call anachronistic ideas about the individual, subjectivity, and the body into question, we must surely also revisit our assumptions about gendered identity: both women and men were actively involved in the construction of Bronze Age lifeworlds—lifeworlds that involved fluid and contextually-specific concepts of identity and power, and where inter-personal violence was just one element of a complex range of social relationships.

Comments on Paul Treherne's ‘The Warrior's Beauty’: The Masculine Body and Self-Identity in Bronze Age Europe Katharina Rebay-Salisbury

Twenty-one years after its publication in 1995, Paul Treherne's ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ remains an influential article for scholars interested in the archaeology of the body, gender, and identity in later European prehistory. The archaeology of the body and identity has since developed and grown, becoming a popular field of study in many different regional archaeologies (e.g. Meskell, Reference Meskell1999; Hamilakis et al., Reference Hamilakis, Pluciennik and Tarlow2002; Joyce, Reference Joyce2005; Robb & Harris, Reference Robb and Harris2013). This article, originally conceived as an MPhil dissertation at the University of Cambridge, investigates how the identity of the European Bronze Age warrior emerged from practices and beliefs centring on the human body and its aesthetics.

Treherne presents warrior identities as a pan-European phenomenon and an important part of Europe's long-term social fabric. First formulated in the Bronze Age, a specific way of making identity continues into the Iron Age and beyond well into the Middle Ages. The warrior lives a particular lifestyle, which includes war/warfare, alcohol, riding/driving, and bodily ornamentation (Treherne, Reference Treherne1995: 108, hereafter only page numbers cited); in death, these themes are further developed and become archaeologically visible in burial practices and grave goods. The ‘warrior package’ thus contains several elements, which include personal weaponry, drinking equipment, bodily ornamentation, grooming tools, and horse harness and/or wheeled vehicles (p. 105).

Among the archaeological evidence, Treherne scrutinizes toilet articles such as combs, tweezers, razors, mirrors, and tattooing awls in particular. Male self-identity, according to Treherne, is linked to a specific kind of masculine beauty and achieved through bodily regimes. Treherne's study is unique in that it aims to integrate the concepts of beauty and aesthetics into the large body of literature on Bronze Age war, warfare, and violence. To the modern reader, the catchy and intriguing title of Treherne's article provokes an association of dissonance: beauty is a concept that tends to be associated with femininity rather than masculinity today. The notion of the beauty of the warrior seems at odds with that of beauty. Bodily beauty and physical attractiveness, however, are important for both sexes, although what is considered beautiful is different for men and women; it underlies evolutionary principles of sexual selection and connotes health, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism (Grammer et al., Reference Grammer, Fink, Møller and Thornhill2003).

Further, Treherne's is one of the few articles that explicitly thematize masculinity, not only theoretically (as Knapp, Reference Knapp1998 has done admirably), but using archaeological evidence constructively to paint a vivid picture of what a particular kind of male identity might have been like. As such, he fulfils the call for understanding the warrior identity as one of ‘divergent, multiple masculinities’ (p. 91).

The development of a warrior ideology is tied into two large-scale social shifts in later European prehistory. The first concerns a shift from an ideology of place and community in Late Neolithic/Copper Age societies to an ideology of individual and personal display, which characterizes Bronze Age societies (p. 107). This shift took place at different times in different places, notably in a first wave during the fourth and third millennium BC (associated, for example, with Bell Beakers). Burial in communal, megalithic tombs gives way to funerary rites that include the interment of a single body in an individual grave, with personal grave goods including prestige goods acquired through long-term exchange networks. Social categorization, including gender and status, was achieved and played out in elaborate funerary rituals, but they were fleeting events: as the body was only visible for a very short time, it had to be represented in a very formalized and stereotyped way to communicate the message of identity unambiguously, ‘fixing an image of the deceased’ in the memory of the participants in the funeral (p. 113).

A second wave of ideological change began in the mid-second millennium bc (associated with the central European Middle Bronze Age) and intensified towards the Iron Age: a ‘differentiated warrior ideology’ developed from a ‘generalised male ethos’ (p. 108). Traditionally, this has been interpreted in terms of increasing social hierarchies and the rise of chiefdoms. Importantly, the warrior identity now includes membership in a specialized group, attached to a patron in paramount position. Warriors engage in a system of relationships of hospitality and reciprocity, which includes exchange, the consumption of alcohol, a shared belief system, shared daily life, and ritualized warfare (p. 109), accompanied by cultural emotions such as honour (see Péristiany, Reference Péristiany1966).

Archaeological evidence of this change include the sword—the first object designed solely for combat—among other weaponry and sets of drinking vessels which go beyond meeting an individual's needs, ornaments that ‘accentuate every part of the body and its movement’ (p. 110, a theme further developed by Sørensen, Reference Sørensen1997, Reference Sørensen, Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010), and an emphasis on textiles as well as ‘toilet articles’.

Toilet articles are artefacts specifically designed for bodily grooming and decorating, such as combs, tweezers, razors, mirrors, and tattooing awls. Shaving, combing, plucking hair, manicuring nails, scarification, and tattooing are argued to be part of the daily routine of taking care of the body. Like weapons, toilet articles show signs of wear and tear, which suggests they were used to achieve ‘beauty in life’. Bog bodies with exquisitely manicured hands, which requires attention over extended periods of time, attest to daily self-care. Further evidence comes from Bronze Age anthropomorphic representations with carefully shaved and groomed hair. The aesthetics of the warrior were achieved through reflexive, personal action; they were important in life and death, ‘mutually constituting one another and together the individual's self-identity’ (p. 125). Toilet articles might have also played a role in specific rituals for particular occasions, e.g. before entering battle or during funerary activities; the fact that they were placed around the body in the grave points to their use in the preparation of the corpse or in ritual mourning.

At this point, I have always wondered why Treherne did not develop this argument one small step further: namely, to see toilet items as means of identity transformation. By employing bodily rituals such as shaving, cutting, and grooming hair, the transition between different kinds of male identity—perhaps that of the warrior and that of a more civil nature—could have been marked and achieved. Multiple masculinities may have had different appearances. The warrior identity would then appear less fixed, although perhaps bound to a certain age and status group or group membership, and more fluid, situational, and temporal. The warrior identity could have been taken up on particular occasions by different people, at times perhaps even by women.

Interestingly, the discussion of beauty is centred on hair and nails, and there is little discussion of other bodily constituents of beauty. For the warrior especially, attractive body proportions with a lean body mass and well trained and defined muscles would have certainly been the ideal, and could only be achieved through regular training. Bronze and Iron Age body cuirasses (e.g. from Kleinklein, Austria: Egg & Kramer, Reference Egg and Kramer2013) with hints of muscle lines are indicators of such beauty standards.

Treherne's article develops theoretical thoughts on transformations of ideology and the emergence of elites. He reacts against the prevailing interpretation of the focus on the human body in the grave as a medium of ideological expression, with the grave as the arena of power negotiation and the ‘ideology of prestige display’ employed in legitimization through mystification. The mantra of funerary archaeologists at the time—that the ‘dead do not bury themselves’ (see Parker Pearson, Reference Parker Pearson1999: 84)—had begun to disregard and overshadow the lives of the buried people. Drawing on materialist formulations of ideology, tension between ideology as illusion and social reality had emerged. Treherne, however, insists that people lived their ideology as real (p. 116). Grave goods chosen for display and conspicuous consumption as well as ostentatious funerary rituals are expressions of social practices and beliefs people actually subscribed to. To explain why specific objects are selected for social legitimization and aggrandizement, their specific socio-historic context has to be taken into account.

Formulating his own philosophical position on the body against the work of Althusser, Merleau-Ponty, Bourdieu, Giddens, and others, Treherne stresses the ‘fundamental materiality of the body and self’ (p. 119). The body is more than a social construct, a product of discourse or the symbolic; the self is practically mediated and lived through the body. Self-identity emerges through sensory exploration with the body as the medium of experience; self-care and beauty maintenance, therefore, play an important part in identity construction.

To explain why beauty was important to the Bronze Age warrior, Treherne draws on sources and scholarship on the heroes of Greek Antiquity (e.g. Vernant & Zeitlin, Reference Vernant and Zeitlin1991; Shanks, Reference Shanks1999). In particular the (lack of) beliefs in a life after death meant that the self could only transcend death in the minds of the living (p. 123). Fixing the image of the deceased in the mortuary sphere was therefore paramount, because only memory preserved the deceased in the social discourse (p. 124). The emphasis on beauty counteracted the notions of mutilation, dismemberment, and decay associated with the corpse; elaborate funerary practices helped to cope with the emotion of existential anxiety and counteracted forgetting.

These notions are not necessarily apparent from the archaeological evidence alone and they raise questions about the applicability of the concept of the ‘warrior's beauty’. Treherne's focus on a detailed interpretation of the warrior identity led him to neglect temporal and regional differences; and the extent of the phenomenon remains vaguely defined. Treherne traces roots in the emerging urban societies of the Near East and Anatolia (p. 108), from which elements were selectively adapted; a part of the ideological transformation towards an emphasis on the individual seems anchored in northern and western Europe (although other forms of personhood than the individual may have prevailed; see Fowler, Reference Fowler2004) and does not fit central and eastern Europe in my opinion, where single graves have a much longer pedigree. Cemeteries with individual graves and personal grave goods were already common forms of body disposal during the LBK (Linearbandkeramik, c. 5500–4900). Subsequently, the deposition of ‘multiple and fragmented bodies’ in cairns, passage graves, and other megalithic structures became popular from Scandinavia to Iberia (Hofmann & Whittle, Reference Hofmann, Whittle and Jones2008: 296), but remained a northern and western European phenomenon.

The ‘differentiated warrior ideology’, in contrast, has perhaps most archaeological support in central Europe, where social difference became expressed through burial practices and grave goods since the early second millennium BC at the latest (examples include the ‘princely graves’ from Leubingen and Helmsdorf, Germany; Meller, Reference Meller, Meller and Schefzik2015: 245). Treherne, however, seeks interpretative analogies in much later Greece. And although the warrior identity is discussed as a historically situated product of time and place (Joyce, Reference Joyce2005: 150), one wonders if the combination of groups of males engaging in violence, intoxication, and beautification is not indeed a cross-cultural phenomenon. Specific to the European Bronze Age are then merely the burial practices and the specific kind of prestige good economy tied into metal circulation.

It further remains unclear how broadly the concept of the ‘warrior's beauty’ applies within a given society. Does the ethos of the warrior form part of the general social ideology, adopted by every male of a certain age group, or how selective was membership in the warrior society? Treherne laid out how elite warriors had a lifestyle that involved risk and violence, but also of luxury and excess, apparent in valuable weaponry and bodily grooming, and with it a worldly existence of honour, glory, and beauty to be remembered so as to transcend death. However, what about the common fighter? The family father defending his farmstead, the youth gang raiding the neighbouring village, the mercenaries, and those forced to fight for others’ causes?

It seems that the Bronze Age elite warrior was similarly removed from those fighters as the officer in command is remote from the common soldier today, who, through discipline, control, and subordination, emerges as a non-individual (p. 128). The unknown, anonymous soldier encompasses all nuances ranging from the operator of a killing drone to the injured and traumatized homecoming hero. Perhaps it is time to shed light on the diversity of fighters in later European prehistory, too.

The nature of warfare and violence and its associated archaeological evidence in the form of weaponry, defensive architecture, and trauma on human remains has not lost its appeal since the publication of Treherne's article (e.g. Osgood & Monks, Reference Osgood, Monks and Toms2000; Parker Pearson & Thorpe, Reference Parker Pearson and Thorpe2005; Otto et al., Reference Otto, Thrane and Vandkilde2006; Peter-Röcher, Reference Peter-Röcher2007; Uckelmann & Mödlinger, Reference Uckelmann and Mödlinger2011). Krieg, the current exhibition at the Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte in Halle (Saale), traces the origins of war in the Neolithic (Meller & Schefzik, Reference Meller and Schefzik2015). Anthony Harding perhaps best described the chronological and regional variations in the evidence for fighting. He found the characterization of Bronze Age warriors as a war-band engaging in inter-group raiding more to the point (Harding, Reference Harding2007: 169), although he too maintained the existence of an encompassing ideology of honour, prestige, and violence. Kristian Kristiansen and Thomas Larsson (Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005), as well as Richard Harrison (Reference Harrison2004), stressed the religious and ritual role of the warrior. A persuasive interpretation of Bronze Age religion on the basis of the iconography on razors has been put forward by Flemming Kaul (Reference Kaul1998). The idea that the warrior's self-identity was connected to the maintenance of bodily ideas, however, was nowhere else formulated as concisely as in Treherne's article—it seems to have stood the test of time.

Warrior's Beauty: Revisited from a Nordic Perspective Sophie Bergerbrant

Paul Treherne's article ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ was published in the Journal of European Archaeology twenty-one years ago (Reference Treherne1995); it remains the most downloaded article in the history of the European Journal of Archaeology.

The article was a reworked version of his MPhil dissertation submitted to the University of Cambridge. In it he argued for the need to revitalize and revise the concept of the ‘warrior aristocracy’ (Kriegeradel in German). The article thus redefined the warrior ideal, both in life and in death. Treherne emphasized tangible, personal consumables that were essential for identifying this developing status group, and these centred around four important themes: weaponry, drinking equipment, bodily ornamentation (toilet articles), and horse harnesses and/or wheeled vehicles. He pointed out that not all attributes were present in all cases of warrior graves, and that a distinct form of masculinity, which was present both in life and in death, was central to the warrior ideological complex. He argued that a warrior ideal and lifestyle was born in or around the Bronze Age and that it endured for an extended period in history.

Treherne's contribution was an important catalyst for reviving the topic of the warrior class and ideal in history. Many studies have followed since (Vandkilde, Reference Vandkilde, Otto, Thrane and Vandkilde2006a: 57), and Treherne's article can be seen as having had a significant role in this revival. Indeed, it has been one of the inspirations and starting points for numerous studies about prehistoric masculinity. It has also been referred to in many subsequent Scandinavian studies (e.g. my own PhD: Bergerbrant, Reference Bergerbrant2007), and in studies about warrior graves (e.g. Sarauw, Reference Sarauw2007) and warrior identity (e.g. Skogstrand, Reference Skogstrand2014). However, the article's emphasis on the longevity of the warrior ideals has, in many ways, led the notion that ‘warrior identity’ was a monolithic cultural norm through many periods and regions, effacing subtle variations and culturally specific views of warriors. For example, Skogstrand (Reference Skogstrand2014: 251–56) has shown that warriors disappear from the archaeological record on Funen in the Early Pre-Roman Iron Age; and, when they reappear, in the Late Pre-Roman Iron Age, the warrior role has profoundly changed from the Late Bronze Age form described by Treherne. Despite this, Treherne's contribution provided a key to opening up new angles for the study of masculinity, although explorations of gender and masculinity are unlikely to have been the conscious or primary aims of the author as it is largely grounded in a different body of theory from most gender and masculinity studies. It also has quite a narrow focus, with the warrior class being treated as the only male identity worth defining, while today we are more likely to acknowledge the permutations and variations of masculinity (e.g. Skogstrand, Reference Skogstrand2014). Indeed, a close study of the male costumes recovered from the anaerobically preserved Danish oak log coffin burials has shown that there are at least two, and probably more, variations in male gendered attire, only one of which could be related to warriors (Bergerbrant, Reference Bergerbrant2007: 50–54; Bergerbrant et al., Reference Bergerbrant, Bender Jørgensen and Fossøy2013).

As the title indicates, Treherne's article focuses on appearance and the beauty of the warrior, the softer and aristocratic side of warriorhood: the flashy weapons, the horse riding/chariots, the drinking, and the grooming. These are the positive sides that create bonds between males. Although it also claims to touch upon the darker sides of warriorhood, it really only mentions the actual hardship of a warrior lifestyle, i.e. war, and even that gets only a brief mention. Lately, remains of large-scale warfare have been excavated in northern Europe, such as at Tollense for the Bronze Age (Jantzen et al., Reference Jantzen, Orschiedt, Piek and Terberger2015) and Alken Enge for the Iron Age (Holst, Reference Holst2014), both showing the more brutal and unsavoury side of warfare. The Tollense publication, for example, demonstrates that many of individuals who died in the battle and ended up in the river were non-locals, and the evidence for their diet indicates that they had been eating millet (Jantzen et al., Reference Jantzen, Orschiedt, Piek and Terberger2015), a plant that did not normally form part of the local diet. The site indicates that warriors travelled long distances, and many died as a result of warfare, as demonstrated by the examples of arrowheads found embedded in skulls (Jantzen et al., Reference Jantzen, Orschiedt, Piek and Terberger2015). Of course, one could always discuss whether these individuals were part of the warrior aristocracy or whether they were ‘mere’ foot soldiers. The first publication about Tollense focuses on the actual remains of warfare found at the site, and, not surprisingly, there is no reference to Treherne's article in the book (Jantzen et al., Reference Jantzen, Orschiedt, Piek and Terberger2015).

The main focus in Treherne's article is the theoretical perspective it puts forward, with the archaeological material being included mainly as an illustration of the idea. The author emphasizes the importance not of a beautiful death as much as that of a beautiful treatment after death and in burial and hints that the presence of beauty in the burial might have been a way to cope with the anxiety that may have arisen after a warrior's death. Drawing on the evidence that swords have been reshaped and toilet-equipment used, he suggested that ‘beauty’ was a fundamental part of the warrior lifestyle, too. Even though the body of the warrior is interpreted as an important part of the self-identity of the warrior aristocracy, the body of the warriors, the skeletal remains, are not brought into the argumentation. Bodies are often an important archaeological source for obtaining information and knowledge about prehistoric warfare. In The Routledge Handbook of the Bioarchaeology of Human Conflict (Knüsel & Smith, Reference Knüsel and Smith2013a) there are no references to Treherne's article either, whereas in The Oxford Handbook of The European Bronze Age (Fokkens & Harding, Reference Fokkens and Harding2013) a number of articles refer to it. The physical sides of warfare and warriorhood need to meet the identity and status side put forward by Treherne. The challenge for the future is to combine these different aspects of warriors in prehistory, and to tell a more complete story as there are always two sides to a coin (see Knüsel, this section).

Over the last ten years there has been a growing interest in the archaeology of the body in research (e.g. Sofaer, Reference Sofaer2006; Borić & Robb, Reference Borić and Robb2008). Many of these studies have shown the importance of connecting the physical body with archaeological interpretations of identity, in line with some of Treherne's arguments. Not only have there been theoretical developments concerning the archaeology of the body, there has also been great progress in scientific analyses that can help us gain information about the body. New developments in isotopic analyses and aDNA have given us new and unique possibilities for investigating the diet, mobility, and genetic heritage of deceased individuals, warriors or not, at a much more detailed level than ever before. So far, the most in-depth studies of this kind have been conducted on female graves (e.g. the new analysis of the Egtved girl by Frei et al., Reference Frie, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerlev, Clarke and Frei2015), but future work on warriors’ graves would clearly expand our understanding of warriorhood in the Bronze Age. An increase in the number of experimental warfare studies has also taken place over the last decade. All these recent developments need to be viewed together for an up-to-date reassessment on the Bronze Age warrior. We might not need to revitalize the archaeology of warfare and warriors, as Treherne's article did twenty-one years ago, but all this new research demands another serious theoretical and methodological discussion to bring together and reassess the different dimensions of warriorhood, both the beauty and the beast.

It is easy to find flaws in an article written two decades ago. The intention here is not to belittle Treherne's article in any way. It was, and remains, a sound and influential text, and it has been an important article for many fields of archaeology. As has been noted above, this article was significant for changing perspectives and redirecting research on warfare and warriors. However, twenty-one years later its contribution and role has changed from being a new and innovative article to being ‘a classic’; a starting point for many fields of research. It set a new baseline upon which we continue to build. The problem is, are we not becoming lazy if we simply go on accepting this article's interpretation as the norm?

The time has come for another young scholar to write a new thought-provoking article with a fresh interpretation on warfare and warriors in order for research to move another step forward, an article that embraces the multitude of ideas and data available through new theoretical and methodological developments within the archaeology of the body, or body-centred archaeology, without forgetting the many important contributions highlighted by Treherne. We should never forget that the beauty of the warrior ideal is always followed by the threat and unpleasantness of warfare. I hope there is someone out there who might be up to the task of again writing an article that challenges our perceptions so profoundly that it shifts and changes the course of many fields of archaeology.

An Iberian Perspective on ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ Sandra Montón Subías

Twenty-one years ago, in his now classic article under discussion here, Paul Treherne brought to the fore the analysis of subjectivity in understanding what happened in the prehistory of Europe. After reviewing the evidence for warriors and warfare, he rejected as ‘deficient’ the ideology-as-a-resource mainstream interpretive models for the Neolithic/Bronze Age transition, and re-evaluated this shift in terms of changes in the construction of the male self. In so doing, he pioneered studies of masculinity, of embodiment and symmetrical analysis in archaeology. In addition, his work remains a fine example of the role that prehistory can play in the construction of world history.

Contrary to the quite common conviction that interest in warfare and warriors is mainly a product of the 1990s, I regard the subject as deeply ingrained in the fabric of archaeology. Indeed, the emergence of militant male warrior elites has been considered inherent to processes of growing social complexity since the beginning of our discipline (see Siret & Siret, Reference Siret and Siret1890 as an early example from Iberia). Although frequently theoretically underdeveloped, concepts such as warriors, conflict, instability, warfare, and militarism have been widely used in the archaeological literature of all time. Poorly developed theorizing is, in my view, not so much related to a lack of interest or a conscious wish to pacify the past (as stated, for instance, by Keeley, Reference Keeley1996), but to the very idiosyncrasy of archaeological schools of thought and background assumptions that have taken the phenomenon for granted (see Aranda Jiménez et al., Reference Aranda Jiménez, Montón Subías and Jiménez-Brobeil2009 as an example, again from Iberia).

Within culture history, for instance, the theme was ubiquitous in the form of studies of weaponry (especially typologies), which were and are widely used as fossil types to define and characterize cultures, and to construct temporalities and chronological sequences across the whole of Europe. From the 1970s onwards, growing attention (from heterogeneous perspectives too) to the evolution of social complexity during the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age also correlated the increase in social hierarchy with the rise and consolidation of a male body of warriors. Treherne drew on the same material evidence handled by these previous studies (new specialized weaponry, horse harness, wheeled vehicles, ornaments, and grooming tools) and accepted them as proof of new war-like practices and body language. However, he rejected the modernist dualistic thinking that took these shifts to merely represent a change ‘from an ideology of place and community to one of the individual and personal display’ (Treherne, Reference Treherne1995: 107, hereafter cited by page number only). To him, the Neolithic/Bronze Age transition was, first and foremost, an ontological process.

‘The Warrior's Beauty’ connected the emergence of individualization and personal display in the archaeological record with a new style of life and changes in what it was to be a person (p. 122) and, more specifically, in male self-identity (p. 106). Warrior paraphernalia did not, thus, allude to a restricted elite mobilizing ideology as an external resource for its own benefit—as if persons and ideology belonged to different plans of action, as ideology could embrace structured thoughts detached from people's actions—but to new men's embodied understandings of themselves, their identity, and their way of being in their surrounding world.

Having set out the outline of Treherne's argument, I would like to point out how valuable I find the identification of general trends in prehistory that may be related to concerns of our current times, without doubt a clear merit of Treherne's overview. Maybe because I teach an MPhil course on world history and most of my departmental colleagues are historians of the written sources, I have for some time insisted on how important prehistory is in the construction (and teaching) of world history. Perceived sometimes as a remote (and even exotic) domain, it is also often thought to be unrelated to problems of the present day. However, prehistory saw the birth of many different processes that have moulded the world to its actual shape. The fact that present social and gender inequality, existing identities and ways of being a person, and cultural values and attitudes have been formed by complex long-standing processes beginning in prehistory, and that these can only be well understood and modified in light of their historical backgrounds, has been insufficiently explored.

I find it worrisome, however, that long-term reviews are usually constructed to enhance social change(s) at the cost of social continuity(ies). Because I find Treherne's contribution to fit this tendency, I will now focus in greater detail on his main subject: the emergence of individuality in widespread areas of Europe. My intention here is to discuss the article on its own terms and not so much to point out missing topics that fall outside Treherne's purpose.

Fundamental to the author's argument is the relationship between material culture, the body, and the new type of subjectivity incarnated in the male warrior. According to Treherne, previous works had not really grasped the reasons why objects designated as ‘prestige items’ (an expression that he considers reductionist) are those and not others. Mainly considered as signs of elevated status, their intricate and vital relationship with the manipulation of the warrior's body had remained unattended. Pioneering symmetrical archaeology, Treherne claims that these goods are not only expressing but also constructing a new ‘notion of self and personhood, grounded in changing attitudes to and practices in, on, and through the body’ (p. 125). However, to me, the importance of the body is more announced by Treherne than it is explained. Even when, inspired by works about the Homeric warrior, he assumes the centrality of the body in societies with no body/mind dichotomies, the reader may remain mystified by why the body is so paramount in constructing individualization and differentiation. At this point, I would like to draw attention to a series of works that have contextualized the importance of the body for personhood construction in the framework of oral societies (especially Hernando, Reference Hernando2002, Reference Hernando2012; Moragón, Reference Moragón2013).

Drawing also on the absence of the body/mind dichotomies and on studies promoted (among others) by Norbert Elias, Walter J. Ong, and David R. Olson, such works have explained that, in prehistoric oral societies, there must have been no disconnect between what persons were and their bodies, no fracture between what persons thought they were and what they actually were. Persons became selves through their embodied actions. Under such circumstances, the body was precisely the main mechanism (instead of abstract thinking and reflection) to construct and manifest identity (through its management, movements, actions, and associated material culture). In this sense, the importance of the body in self-hood construction was nothing new to Bronze Age Europe. However, while community belonging was previously performed, Bronze Age warriors set themselves apart and emphasized difference. The difference was thus between being a part of and being apart from, but always through the body.

However, and here I refer again to the change versus continuity issue mentioned before, it is not possible to be apart from something without at the same time being a part of it, as Almudena Hernando has shown in her works. While most scholarship has read Bronze Age warrior's gear, she argues, in terms of individuality and difference, it has at the same time ignored its meaning regarding relational bonding. While warriors were setting themselves apart, they were simultaneously bonding with new peers (warrior fraternities), and thus maintaining, although in a new fashion, relational identity (Hernando, Reference Hernando2012: 137–41). Treherne thus ignores relational mechanisms that remained in the construction of the new subjectivity. In this sense, we could say that Treherne's is a masculinist study on masculinity. In focusing only on individuality and social change, he is stressing values that define hegemonic masculinity in the present and dominate the mainstream writing of (pre)history (see on this issue Hernando, Reference Hernando2012 and Montón Subías & Lozano, Reference Montón Subías and Lozano2012).

In mentioning these flaws (in my view) I would not like to diminish the article's merits. I regard it as a fundamental piece in archaeology's literature, not surprisingly ‘the most downloaded paper in the entire EJA archive’, as Catherine Frieman mentioned when she invited me to contribute here. Paul Treherne is among the first scholars explicitly reflecting on the construction of the male self in prehistory. In the 1990s, when gender studies in archaeology were mainly perceived as women's affair, it was very important to reflect on the fact that men also had gender. In addition, Treherne's article made very clear that, during prehistory, there were different ways of being a person and, importantly, that individuality had a (pre)historic starting point. That is beyond any doubt, and as such needs to be acknowledged.

I want to insist, however, on how important it is to complement overviews such as Treherne's with studies of social dynamics, values, and principles that have been marginalized from the mainstream of scholarly discourse and thus left outside history. To continue with examples from Iberia, different works—from a feminist or feminist sensitive standpoint—have already attempted to redress imbalances created by this neglect, focusing on the role of stability, continuity, recurrence, relationality, and interdependence (see, also for the Bronze Age, Colomer et al., Reference Colomer, González Marcén and Montón Subías1998 and Aranda Jiménez, Reference Aranda Jiménez, Berrocal, Sanjuán and Gilman2013 as two examples). Only by considering the interplay between change and permanence can social complexity and diversity in the past be comprehended, changes be understood in their full dimension, and an inclusive World (pre)History be constructed. It is not only a question of fairness or representation; it is a question of improving archaeological and historical knowledge.

The Warrior's Seduction Joanna Sofaer

In his novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan describes the attitude to virtue of his central character, war hero Dorrigo Evans:

‘Dorrigo Evans hated virtue, hated virtue being admired, hated people who pretended he had virtue or pretended to virtue themselves. And the more he was accused of virtue as he grew older, the more he hated it. He did not believe in virtue. Virtue was vanity dressed up and waiting for applause.’ (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2013: 53)

Virtue, then, is not a matter of self-identity, which, as Dorrigo Evans's story unfolds, is full of complexity and doubt borne of self-knowledge and introspection. Instead, virtue in relation to self does not really exist, or at most is shallow and showy. It emerges primarily from the desire of people to attribute qualities to others as if to give themselves hope in a world where honour and heroism seem in short supply.

As I write, the news is full of refugees fleeing conflict, stories of soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and terrorist atrocities. Perhaps it is precisely because of the lack of virtue in the modern world that the romantic vision of a warrior golden age offered by Treherne is so appealing. Yet it is both striking and disturbing that the combination of heroic traits identified by Treherne—a focus on hair and grooming as a marker of identity and lifestyle, the search for glory, eternal remembrance, and heroic death—are hallmarks of a range of modern military and terrorist groups, albeit in different ways. One thinks of the ‘buzz-cut’ in the US military, the immaculately groomed and uniformed soldiers of the North Korean regime, and the propaganda promulgated by the self-styled warriors of Daesh. In each of these cases, the individual male body is linked to the body politic (Brod & Kaufman, Reference Brod, Kaufman, Brod and Kaufman1994: 8). There seems very little of beauty here.

I do not doubt the importance of social categories in the Bronze Age, that ‘the warrior’ may have been one such category, or that the body, its display, and adornment played a significant role in the mediation of Bronze Age social relations. However, ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ proffers a highly sanitized and hegemonic view of Bronze Age masculinity that does little justice to the complexity of human identity (see Cornwall & Lindisfarne, Reference Cornwall and Lindisfarne1994). Asserting that there was a ‘coherent warrior lifestyle’ does not mean that all eligible men conformed to it. The evidence for how regularly masculine ideals were enacted and sustained, or how individuals entered the warrior ‘class’ is thin—to what extent was it ‘action-based’ or inherited? Similarly, the extent to which warrior values can be exclusively equated with social status, or whether status might be expressed or achieved in a variety of other ways, is unclear. One might also ask to whom the performance of beauty was directed and whether it took place in public or in private. In an age before mirrors, did men groom themselves or was this done for them? In the case of the latter, was identity, therefore, a co-creation? How might modifications to the body aim to meet the expectations of others rather than of self? Furthermore, the Homeric epic poems (a key strand in Treherne's argument) post-date the Bronze Age (Finkelberg, Reference Finkelberg1998). Thus, they cannot be understood to represent a Bronze Age reality, but are likely to represent an amalgam (Snodgrass, Reference Snodgrass1974) or ‘unhistorical composite’ relevant to the values of the intended audience (Osborne, Reference Osborne1996: 153). Yet these unresolved questions, tensions, and deficiencies often seem to be willingly overlooked, such is the draw of Treherne's narrative.

‘The Warrior's Beauty’ remains one of the few unambiguous discussions of masculine identity in the prehistory literature and here, too, lies some of its allure. It is useful to recognize that the article was written in the early days of gender archaeology. The potential of mortuary contexts for gendered analyses in terms of the relationship between the physical body and grave goods had recently been highlighted in a range of publications (e.g. Bertelsen et al., Reference Bertelsen, Lillehammer and Næss1987; Gero & Conkey, Reference Gero and Conkey1991; see also Sofaer & Sørensen, Reference Sofaer, Sørensen, Tarlow and Nilsson-Stutz2013). While these and many other subsequent works aimed to rectify the ‘invisibility’ of women and other social groups, on the whole men have remained visible but ‘unmarked’ (Alberti, Reference Alberti and Nelson2006: 401). Treherne's article, therefore, offers a form of analysis that remains largely unavailable elsewhere. It may also provide a potential point of self-identification for modern men, something noticeable in responses to ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ in my own teaching practice: a delight (and relief) that the study of social identity and gender has a place for men and is not just about women! However, whether the enduring popularity of the article is due to the particular nature of the insights it provides into the Bronze Age and the nature of masculinity, or whether it results from disciplinary failure to develop a range of recognizable narratives about men (and thus a lack of alternative points of contact with the past for young men in particular), is unclear. In claiming that the origins of feudalism lie with the Bronze Age warrior, Treherne positions the Bronze Age in a particular way with regard to the construction of modernity and creates a seductive legacy for modern masculine identity. However, this apparent legacy deserves scrutiny since the elision of two distant and entirely different periods is awkward. There is, therefore, potential for a vibrant, more contextually-specific discussion that enriches archaeology by recognizing dynamics, complexity, and nuances in the interwoven histories of women and men.

Though presented through the lens of theoretical debates surrounding various Marxist and post-processualist understandings of the expression of ideology that took root in the 1980s and 1990s, much of the article reads as if it could have been written more recently. Re-reading ‘The Warrior's Beauty’ twenty-one years after its publication, it is striking how current some of the terminology is. Terms such as ‘embodiment’, ‘performance’, ‘subjectivity’, and ‘personhood’, along with an explicit focus on the physicality of the body as a source for the construction and mediation of identity, resonate with contemporary concerns regarding the nature of past human experience. The article, therefore, retains disciplinary relevance, although it is notable that, in contrast to the extended discussion of ideology in the first part of the publication, the theoretical vocabulary that may be of most interest today is comparatively under-referenced and used relatively loosely. A lack of explicit ‘positioning’ in terms of the shades of meaning that accompany some of these theoretical strands may be an additional reason for the article's continuing appeal. In other words, it is easier to agree with generalities rather than specifics. A number of highly relevant volumes arguing both for and against Treherne's position in relation to the body had already been published prior to 1995, but are not cited by him (e.g. Butler, Reference Butler1990, Reference Butler1993; Featherstone, Reference Featherstone1991; Shilling, Reference Shilling1993; Cornwall & Lindisfarne, Reference Cornwall and Lindisfarne1994; Moore, Reference Moore1994). It is, therefore, interesting to consider whether the impact and continued relevance of the publication reflects its original aims and intentions. Rather than continuing to use the article in order to understand masculine identity, it may be profitable to return to, and critically engage with, Treherne's broader initial goals and arguments regarding the lived experience of ideology. Today, when it seems that ideology is everywhere, a critical re-reading of Treherne's text has particular poignancy in reflecting upon the potential role of ideology in the development of human experiences. It challenges us to consider how the expression of individual and group action is tied to beliefs about the world and one's place within it.

Though Treherne's article retains its popularity twenty-one years after its original publication, this is not necessarily due to its complete veracity or the bullet-proof nature of its arguments and evidence base. Instead, it appeals to the all too human desire for his narrative in our own turbulent world. It speaks to the pressing need for particular kinds of histories and thereby highlights both missed opportunities and constructive disciplinary developments. It will doubtless continue to be widely read as new generations of archaeologists find inspiration in its pages.

The Ongoing Significance of Paul Treherne's Classic 1995 Article ‘The Warrior's Beauty: The Masculine Body and Self-Identity in Bronze-Age Europe’ ( Journal of European Archaeology, 3(1), 105–44.) in Recognition of the 20th Volume of the European Journal of Archaeology Christopher J. Knüsel

This review comes in the midst of what has been described as a ‘crisis of masculinity’ in societies across the world, a social phenomenon that is characterized by a male attainment deficit, increased incarceration and recidivism, poor employment prospects, and low self-esteem. In 2001 The Economist noted that ‘throughout the world, developed and developing, antisocial behaviour is essentially male. Violence, sexual abuse of children, illicit drug use, alcohol misuse, gambling, all are overwhelmingly male activities’. The article goes on to observe that ‘Men […] have been robbed of their traditional roles as providers, protectors and even procreators’. Nearly fifteen years later, in 2015, The Economist characterized this trend in rich countries as ‘no job, no family and no prospects’.

This description of contemporary masculinity is completely at odds with the image Paul Treherne paints of masculinity some 4000 years ago in ‘The Warrior's Beauty’. Treherne characterizes these Bronze Age warriors as epitomized by a concern with physical appearance, as implied by items described as ‘toilet kits’ found in their graves, consisting of combs, razors, and tweezers, which probably groomed them in life and at death. He describes these warriors as ‘beautiful’, adorned in shiny gold and bronze metalwork displayed on woollen garments, with elaborate, well-groomed, and probably distinctive hairstyles and perhaps facial hair or lack thereof. They may have employed make-up, perhaps using the peculiar wooden ‘spatulas’ sometimes found in burials, contemporary examples of which were found with Gristhorpe Man (Melton et al., Reference Melton, Montgomery and Knüsel2013 and see below) and another with the Amesbury Archer (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2011: 75). These Bronze Age men engaged in feats of conviviality—drinking bouts and feasts—and in the skilled use of the first specialized arms requiring both physical co-ordination and more assiduous training. They had personal character and their appearance expressed a developed self-identity based on a weapon-bearing warrior lifestyle. Perhaps, like their later medieval counterparts, they evinced prowess; not only physical skill, but bearing and poise in conduct (see Knüsel Reference Knüsel, Baadsgaard, Boutin and Buikstra2011, Reference Knüsel, Whelehan and Bolin2015) that won glory, renown, and remembrance that formed the goals of life and contributed to a good death (Bloch and Parry, Reference Bloch, Parry, Bloch and Parry1982: 15; Binski, Reference Binski1996) as represented by an elaborate single burial beneath a mound visible for all to see. These men seem to have exuded confidence, self-esteem, and self-assurance within their societies, as reflected and represented in the treatment of their bodies in death. Treherne draws splendidly on the notion that ‘the body and its treatment becomes [sic] an artefact of and canvas for symbolic and social expression’ (Knüsel et al., Reference Knüsel, Batt, Cook, Montgomery, Müldner, Ogden, Palmer, Stern, Todd and Wilson2010: 306).

Although Treherne's article is admirable for highlighting the accoutrements, material culture, and aspects of the social context of these Bronze Age warriors, it inspired my interest, in part, because of the areas in which it is least developed. Despite repeated mentions and discussion of the body from a metaphysical point of view based on funerary remains, few remains of bodies enter into the piece and when they do they involve apparent manipulations of the remains of the deceased with presumed symbolic value that has more recently been ascribed to other processes in many instances. In effect, this leaves the use of ‘male’ and ‘masculine’ in his treatment in the same realm as the use of the word ‘prestige’ that is critiqued so thoroughly in it. The physicality of these warrior males is left untouched—their height, weight, physique, their maladies and wounds, the extent of their masculinity as defined by masculine physical traits—and even if all the individuals accompanied by such objects were indeed males, all of these attributes can be determined from the analysis of the skeletal remains of the deceased. Were these men physically distinctive? Where did they come from, and to whom were they related? Did these physical attributes also have an influence on the appearance and status of the warrior as much as their dress and accoutrements? Some of these questions have been answered in the twenty-one years since the article was published, but many have not, and geographic and temporal coverage is uneven. These corporeal attributes could act as a complement to, and contribute much, if not more, to the ‘substantive content and implications for subjectivity’ (Treherne, Reference Treherne1995: 117, hereafter cited by page number only), to address ‘the relationship between the body and subjectivity’ (italics in the original) implicit in the objects found with the dead. This means that the template provided by Treherne could be judged against individual Bronze Age warrior graves, and it could inspire similar approaches in later periods, as indeed it did in the medieval examples referred to above.

Deeper consideration of the physical remains of the dead would also contribute to better understand the placement of objects on the body with respect to skeletal remains; this would do much to unravel the ideological underpinnings of these objects, revealing in the process a grammar of symbolic intent present in the patterning of material with respect to the remains of the body.

The corporeal attributes of these well-appointed male burials can also provide a means to study the social effects of ideologies that permeate all forms of human practice and whether or not their manifestations were indeed a conspiratorial practice of a ‘small group of cynical men’ (p. 115) to obtain a pre-eminent social status that conferred membership to ‘the warrior fraternity’ (p. 114). As noted by Treherne, the societies of the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age were not egalitarian (if not before, see below), and it may well be that the activities and behaviours linked to the appearance of these individuals was indeed a conspiracy to legitimate social inequality. And this may have been enforced through threat and fear of retribution—from within social groups and from the outside—that led to the hegemony of groups of people, at least in some places and times. The means to explore these relationships come in two forms: measures of well-being and physical injuries, including weapon-related trauma. Again, both relate to the physical remains of the deceased.

One of the occupants of these Bronze Age single burials, the nearly complete skeleton known as Gristhorpe Man, was buried in an oak log coffin on the coast overlooking the North Sea, near Scarborough in Yorkshire (Melton, et al., Reference Melton, Montgomery, Knüsel, Batt, Needham, Parker Pearson, Sheridan, Heron, Horsley, Schmidt, Evans, Carter, Edwards, Hargreaves, Janaway, Lynnerup, O'Connor, Ogden, Taylor, Wastling and Wilson2010, Reference Melton, Montgomery and Knüsel2013). He was buried with a whalebone-embellished dagger, among other artefacts. Gristhorpe Man and other single inhumations form a distinctive group of ‘tall men’ from the Early Bronze Age in Britain that suggests preferential access to good nutrition and growth environments commensurate with social advantage from birth, stature being a good measure of population and individual health and well-being (see discussion in McKinley, Reference McKinley and Fitzpatrick2011; Knüsel et al., Reference Knüsel, Wastling, Ogden, Lynnerup, Melton, Montgomery and Knüsel2013). These men may have belonged to an inherited social elite for a period of time, though one that was not apparently sustainably inter-generational over the longer term. Gristhorpe Man was of robust build with an enviable body mass, producing a high normal body mass index by today's standards. His was of athletic build. His strongly developed right dominant arm (i.e. humerus) testifies to its use in strenuous physical activities that are likely to have included technological and subsistence-linked activities such as manufacture and maintenance of objects, as in woodworking and metalworking, and pursuits requiring physical effort, including long-distance walking and sport, as well as weapon use. Dietary isotopes suggest that he had benefited from a rich, high-protein diet, which also predisposed him to renal stones. During life he had developed an intracranial tumour, the placement of which may have affected movement of the right side of his body, including his well-developed right upper limb, and his ability to speak and comprehend speech. His remains also show evidence of a chronic infection of the maxillary dentition from dental caries, as well as other carious lesions. These are indications of the physical consequences of a socially pre-eminent lifestyle that included the consumption of cariogenic foods.

Gristhorpe Man had sustained four ante-mortem (i.e. all healed) traumatic injuries, two to his ribs, another to his neck, and yet another to his chin. These attest to an active lifestyle that exposed him to injury. The Amesbury Archer (named after the arrowheads among the grave goods accompanying this Early Bronze Age male burial in Wiltshire) also had sustained a crippling knee injury in his young adult years (McKinley, Reference McKinley and Fitzpatrick2011). A worldwide review of traumatic lesions related to inter-personal conflict found that such injuries occurred overwhelmingly in males from the Bronze Age to the modern period (Knüsel & Smith, Reference Knüsel, Smith, Knüsel and Smith2013b). These sumptuously adorned men and their followers were not only able to deliver injurious blows, but also exposed themselves repeatedly to injury as well.

The Neolithic forms a turning point in the level of violence (Schulting, Reference Schulting, Gowland and Knüsel2006; Schulting & Fibiger, Reference Schulting and Fibiger2012; Smith, Reference Smith, Knüsel and Smith2014) Although there is noticeably more evidence of injuries resulting from interpersonal violence in the Neolithic than in preceding periods, there appears to be a more equal distribution of traumatic injuries between the sexes (Schulting & Wysocki, Reference Schulting and Wysocki2005; Fibiger et al., Reference Fibiger, Ahlström, Bennike and Schulting2013; Knüsel & Smith, Reference Knüsel, Smith, Knüsel and Smith2013b), attesting to the differing circumstance in which these wounds were received. Neolithic warfare appears to have been more about surprise and hit-and-run tactics, as may be indicated by a lack of static, defensible fortified places. Support for this statement comes in at least two additional forms of physical evidence, in addition to skeletal trauma: mass graves and bilateral limb asymmetry. The Early Neolithic mass grave at Talheim, which Schulting (Reference Schulting and Ralph2013: 22) describes as ‘paradigm-shifting’, was the first to provide evidence that apparent ‘tools’ (adzes) were responsible for cranial trauma that resulted in the deaths of multiple men, women, and children (Wahl & König, Reference Wahl and König1987). It was not only in the Early Neolithic that such violence is documented (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Lohr, Kürbis, Dresely, Haak, Adler, Gronenborn and Alt2014, Reference Meyer, Lohr, Gronenborn and Alt2015), other notable examples being known from the Late Neolithic (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Brandt, Haak, Ganslmeier, Meller and Alt2009). Already in the Early Neolithic, males buried with adzes seem to have employed their right upper limbs in activities that predisposed them to thrower's elbow (Villotte & Knüsel, Reference Villotte and Knüsel2014), a disorder linked to single-handed tool-use that probably included weapons.

Schulting (Reference Schulting and Ralph2013: 25) notes that ‘we do not see a specialized warrior identity in the Mesolithic or Neolithic and that every able-bodied male would be expected to perform this role alongside his other roles: as hunter, farmer, herder, fisher, weaver, potter, etc.’. If discernible warrior graves are apparently absent, it appears that their activities seem to have been present. Warriors, then, probably emerged before they became archaeologically visible in the Bronze Age (see Jeunesse, Reference Jeunesse1996), when a more highly organized entourage of (male) warriors and more highly orchestrated warfare that is familiar to historians of the ancient world came into being.

When combined with the type of material associations described by Treherne, these studies have the capacity to break the symbolic/utilitarian interpretive equifinality implicit in apparently socially-identifying objects. In short, a great corpus, made up of theory, historical precedent, and material cultural correlates, lacks a synthetic biological component, and we are thus left with the conundrum of whether elaborately interred individuals constitute an orchestrated symbolic, but in essence unreal or even misleading, representation, or a true reflection of the emergence of a socially differentiated group that contributes leaders, i.e. active social agents, wielding unequal power to influence social change. This question finds its correlate in the work of Härke (Reference Härke1990, Reference Härke and Carver1992) on early medieval weapon burials, which are described by Steuer (Reference Steuer and Randsborg1989) as also representing a ‘warrior lifestyle’ in the early medieval period. As suggested in Treherne's essay, the key to unpicking this knot of ambiguity—to break the equifinality implicit in the term ‘weapon burial’—lies in the physical attributes of individuals buried in elaborate graves.

The emergence of warriors in the Bronze Age may go far to explain some of the population movements/mass migrations that are thought to have taken place on a grand scale in the period (Haak et al., Reference Haak, Lazaridis, Patterson, Rohland, Mallick, Llamas, Brandt, Nordenfelt, Harney, Stewardson, Fu, Mittnik, Bánffy, Economou, Francken, Friederich, Garrido Pena, Hallgren, Khartanovich, Khokhlov, Kunst, Kuznetsov, Meller, Mochalov, Moiseyev, Nicklisch, Pichler, Risch, Rojo Guerra, Roth, Szécsényi-Nagy, Wahl, Meyer, Krause, Brown, Anthony, Cooper, Alt and Reich2015), but such an explanation may also be employed on a local or regional scale to account for the origin of warrior-leaders. This would also help resolve the question of whether individual cases represent true warriors—who had actually fought—and distinguish them from others who were non-combatants buried in ways which mimicked the warrior's beauty, in a manner that is similar to the transformation from warrior to courtier-aristocrat of the Later Middle Ages (see p. 130). This diachronic perspective, hinted at in the conclusion of Treherne's piece, speaks for what appears to be a recurrent and enduring phenomenon of a certain type of masculinity. It seems clear that by the advent of the European Bronze Age, if not before, the martial component of masculinity had emerged, and it continues to be present in a less personally active but increasingly powerful and deadly form in leadership today.

The ‘Beautiful Warrior’ Twenty-one Years After: Bronze Age Warfare and Warriors Helle Vandkilde

The seminal article by Paul Treherne in the 1995 volume of this journal seems to have given rise to a mostly independent thread unrelated to the current surge in warfare research. The role of warfare and warrior aesthetics is briefly discussed against this background.

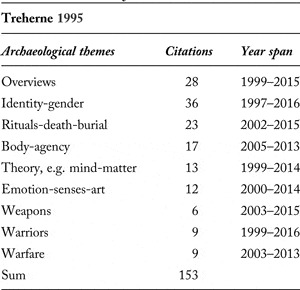

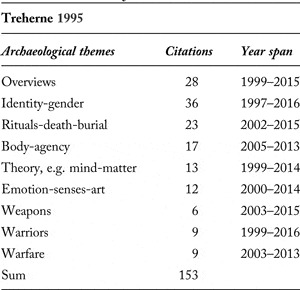

Warriors would seem topical to questions of prehistoric warfare, which until c. 1996 was a marginal subject area in archaeology. Since then, war has gained considerable momentum as a research theme and today the archaeology of warfare is firmly placed in the suite of archaeologies addressed. The brilliant ‘Warrior's Beauty’ paper by Paul Treherne, published in Reference Treherne1995 in the European Journal of Archaeology (then the Journal of European Archaeology) can, given its many citations, be categorized as a high-impact article; it is a frequently accessed article on the journal's website. Against this background, it is pertinent to ask if the study has had a role in driving the current interest in war and, hence, has influenced the new knowledge now emerging. Are the visual appearance and bodily movements of the ancient warrior, sensu Treherne, at all present in the archaeology of warfare now blooming?

In the twentieth century, the warrior was considered a heroic stereotype at the head of an ancient society that was deemed essentially peaceful. But, after the ‘discovery’ of the war-like reality of societies in the late 1990s, warriors have paradoxically fallen out of the Bronze Age research limelight, although warrior elites sometimes figure in interpretations (Vandkilde, Reference Vandkilde, Gardner, Lake and Sommer2016). It is, therefore, timely to assess the value of Treherne's contribution.

An impactful essay ahead of its time

Treherne's essay contains a number of observations and theory-driven hypotheses, which have the potential to throw light on the main strands of change in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe and increase our understanding of the role of the warrior in these societies. In addition, it is a manifesto replete with theoretical insights: classic, mainstream, and scholarly. The position taken is not easily slotted in to any theoretical school or paradigm; the article works equally well as a grand history on an Eurasian scale, and, by contrast, as an examination of the male body and equipment as both unique and reiterated materiality in life and death. This epistemological stance embedded in Classical history may explain the immediate success of Treherne's article, not least in the mid-1990s when much energy was invested in aligning with processual, post-processual, or post-structural persuasions.

Characteristically, the essay works with dualities rather than dichotomies. In fact, the inseparability of ideology and reality on the one hand, and of the body, identity, and personhood on the other, may have been an eye-opener for many archaeologists struggling to make sense of specific archaeological remains, in particular burials: it became clearer that people's beliefs were lived through their social interactions and affiliations, and that concepts such as ‘false consciousness’ tends to victimize, especially, those people ‘without history’ and thence to simplify complex prehistoric realities. People live out their ideologies and form their identities through their bodies in an entanglement where power is an inherent element. In providing a simultaneously sophisticated and straightforward framework for thinking theoretically about archaeological things, data, culture, and change, Treherne was well ahead of his time. First, the essay can be read as a critique of archaeology rooted in philosophy, while at the same time promoting body, gender, identity, agency, the senses, and even history as an interleaved package central to the interpretive agenda. Second, the essay can be taken to be an innovative framework for better understanding the numerous weapons recovered in burials and hoards from around 3000 bc onwards, and here Classical studies and early written sources support the argument well. The immediate impression is nevertheless that this second aspect has not been invigorated to any significant extent by the general academic turn set out by Treherne's essay.