INTRODUCTION

Baalbek is a small city in modern-day Lebanon with some rather big ruins. The megalithic columns of the temple of Jupiter, the well-preserved facade of the temple of Bacchus, and the perfectly circular temple of Venus are part of a complex of Roman buildings that has inspired visitors for centuries (fig. 1). Henry Maundrell, a chaplain to the English Levant Company stationed in Aleppo, opined in 1697 after seeing the temple of Baalbek that it “strikes the mind with an Air of Greatness beyond any thing that I ever saw before, and is an eminent proof of the Magnificence of the ancient Architecture.”Footnote 1 Gustave Flaubert outdid even this sentiment when he confided to his mother in 1850 that, “as for the temple of Baalbek, I had not believed that it was possible to fall in love with a colonnade, but it's true!”Footnote 2 Baalbek would go on to play an outsized role in the history of Romanticism, inspiring architects, poets, and historians over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and becoming one of the preeminent archaeological sites in the Middle East.

Figure 1. Depiction of the ruins of Baalbek with the colonnade of the temple of Jupiter and the surrounding courtyard on the left and temple of Bacchus on the right. Thomas Major and Giovanni Battista Borra, The ruins of Balbec, otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria, London, 1757, Tab. XXI. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03132.

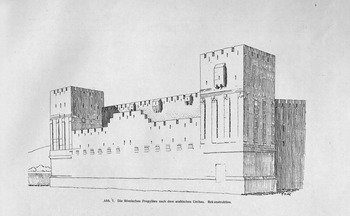

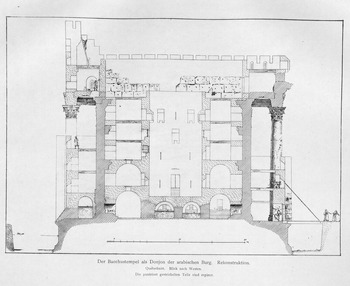

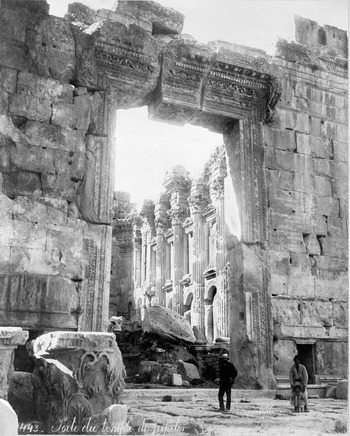

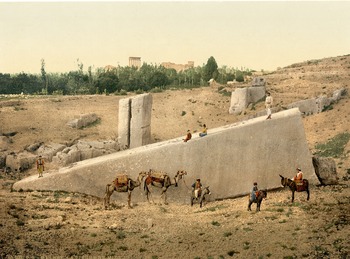

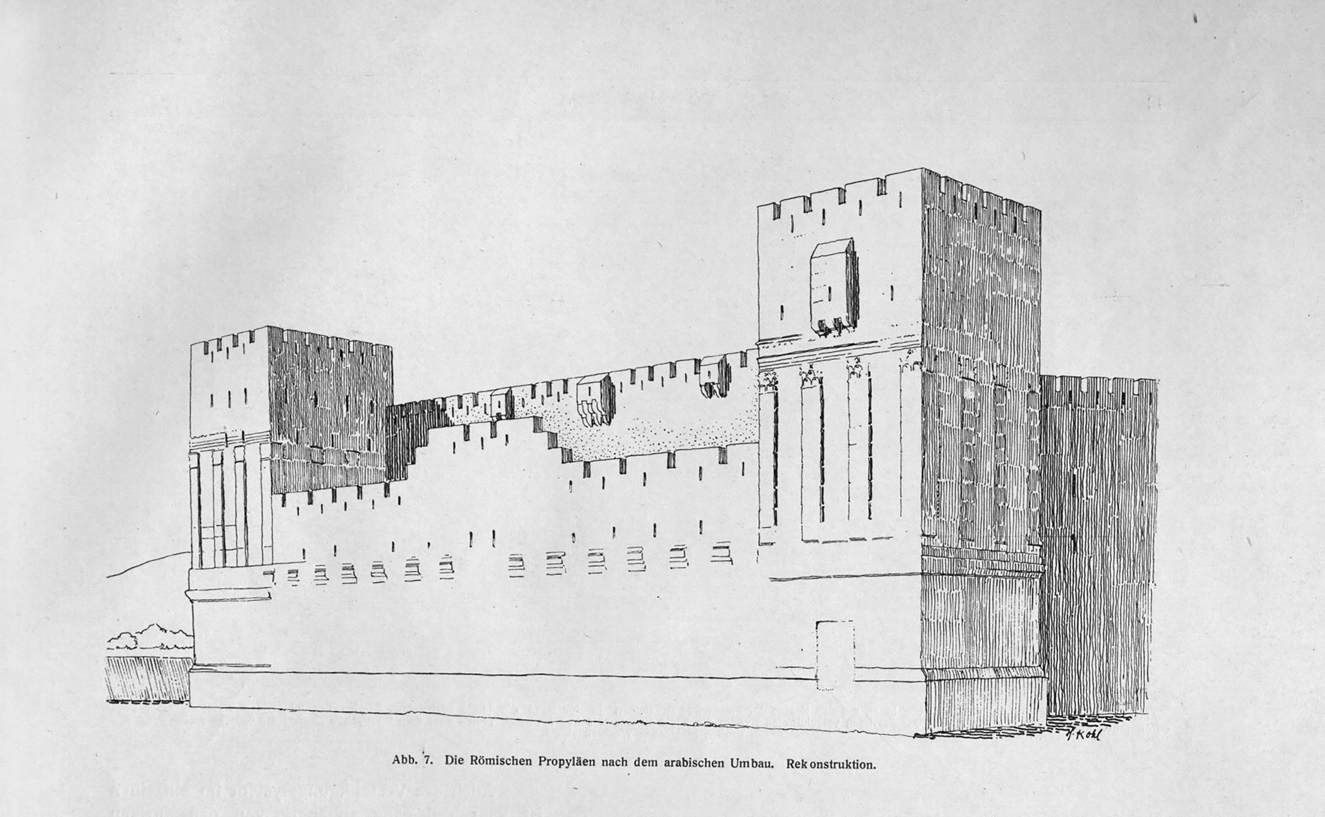

The ruins in Baalbek were not always quite so easy to see though. The complex's identity as the ruin of a Roman temple was largely invisible to both locals and visitors alike. They saw instead a wondrous fortress. They were not necessarily wrong; Byzantine and Mamluk rulers had indeed turned the temple into a castle over the interceding centuries (figs. 2 and 3), and visitors saw the entire complex as a unified whole, unable to parse the different historical layers or indifferent to its historicity. This state of affairs remained the case until European travelers started noticing the ancient temples sometime in the mid-seventeenth century. Seeing Baalbek as an ancient Roman temple became a visual shibboleth, marking those with a modern viewpoint, so much so that twentieth-century scholars termed this sudden recognition of its antiquity a rediscovery.Footnote 3 The aforementioned Maundrell, for example, visited the ruins and quickly recognized them as “anciently a Heathen Temple, together with some other Edifices belonging to it, all truly Magnificent: but in latter times these ancient Structures have been patch'd, and piec'd up with several other buildings, converting the whole into a Castle, under which name it goes at this day.” He decided that “the adjectitious buildings are of no mean Architecture, but yet easily distinguishable from what is more ancient.”Footnote 4 The main interpretative labor for early modern European visitors to Baalbek was to see the ancient temples within the fortress and to situate the monuments within a linear chronology. Since that time, scholars and laypeople alike have become increasingly fluent in the language of ruins. Travelogues, engravings, excavations, photographs, guided tours, and world heritage organizations have literally and figuratively revealed Baalbek to be a Roman temple.

Figure 2. An entrance to the fortress of Baalbek, likely at the southern tower. Maison Bonfils, second half of the nineteenth century. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-04129.

Figure 3. An imagined reconstruction of the citadel built onto the temple of Bacchus during Ayyubid and Mamluk periods. In Kohl et al., Baalbek (1925), 3:41.

Early modern European travelers were able to start perceiving Baalbek's Roman origins due to an appreciation and recognition of antiquity—that specifically Renaissance valuation of the Greco-Roman past. Starting in the fifteenth century, the rediscovery of the written heritage of ancient Greece and Rome formed the literary foundation for the parallel investigation of antiquity's material remnants in the form of monuments, statues, or coins.Footnote 5 By the seventeenth century, antiquarianism coalesced into a methodology that privileged material artifacts and monuments over literary sources as windows onto the human past.Footnote 6 Until relatively recently, antiquarianism was dismissed as the dilettanteish collection of old curios, but now, after decades of research and a plethora of books and articles, it has been redeemed as a forebearer of art history, archaeology, history of religion, and any discipline that uses the lenses of material culture in its analysis.Footnote 7 As recent works by Kathleen Christian and others remind us, there was no single, overarching concept of antiquity or antiquarianism; instead, a multiplicity of local actors began to look at the ancient past, whether or not it was Greek or Roman.Footnote 8 Even in Rome and Florence, the initial centers of antiquarian collecting in the fifteenth century, one can see different groups taking part in antiquarian projects, often with quite different agendas.Footnote 9

It can be difficult to ascertain the existence of antiquarianism as an intellectual project in the premodern Middle East because denizens of the area possessed no readily apparent tradition of investigating the material remnants of the past, not to mention the fact that they did not rediscover, as it were, its Greco-Roman heritage. This is not to say that Middle Easterners were not interested in the ancient past. Authors of so-called universal histories often wrote of the time of Adam and the other prophets, or the reigns of ancient Egyptian or Roman rulers well before Islam.Footnote 10 The Pyramids in particular inspired periodic investigations.Footnote 11 There was not, however, a recognizable and systematic practice of collecting ancient objects or exploring ruins as in the Chinese and European contexts.Footnote 12 For this reason, the story of antiquarianism in the region has largely been narrated as the arrival on eastern shores of a European appreciation of the antique world's material artifacts. At first, historians spoke only of European travelers and scholars discovering and collecting ancient monuments in the face of local indifference to the antiquities surrounding them.Footnote 13 In response, scholars have underscored both how local communities gave significance to ancient objects and sites in unwritten lore and how a modern appreciation of them developed as a reaction to rapacious European looting of antiquities in the nineteenth century.Footnote 14

Today, a new push to write a global history of antiquarianism aims to show that local, contingent knowledge of antiquities helped constitute a connected and universal form of early archaeological knowledge.Footnote 15 For the Mediterranean region, there are even examples of how provincial Ottoman grandees in the early nineteenth century, like the local potentates of Ioannina, ʿAlī Paşa and his son Velī Paşa, made claims on this same classical Hellenic heritage, often arm-in-arm with European antiquarians.Footnote 16 These latest interventions in the scholarship have created a more capacious understanding of antiquarianism, one that encompasses, for better or worse, nearly all interactions with objects from the past: written or unwritten, explicit or implicit, systematic or haphazard. This is a welcome development for historians, but it leaves open the question of the intellectual and cultural role of antiquity in the Ottoman Empire. What material and affective practices did Ottoman scholars cultivate to identify antiquity? How did Middle Easterners make use of the concept of antiquity, and its artifacts, to resituate their own temporality and revive variant visions of political community? In short, is there a possibility of constructing a theoretical concept of antiquity outside of the Greco-Roman (or ancient Egyptian) past valued by early modern Europeans, to find a space of thinking about the material remnants of the past that is based neither on haphazard local knowledge and tales nor on the universal science of modern-day archaeology?

ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī's (1641–1731) descriptions of Baalbek in 1689, and again in 1700, provide a starting point to answer these questions.Footnote 17 The famous Damascene intellectual left behind the only known detailed description of the ruins of Baalbek by an Islamic scholar before the nineteenth century. The passage is not well known among historians today, but the few that have read it have dismissed it as “long but not very informative” or regarded it as a generic description commonly found in Arabic travelogues.Footnote 18 I argue, on the contrary, that Nābulusī's investigation into the ruins of Baalbek was not just casual observation or regurgitated local knowledge but part of a purposeful antiquarian project. He declares it to be part of antiquity after exploring, lamp in hand, the entirety of the complex—from the massive temple ceilings and the fine marble reliefs to the bottomless cisterns and water systems to the small stones splicing the stairs. Yet, Nābulusī, unlike European travelers, does not identify Baalbek as part of Roman antiquity. Nor does he even distinguish between the original structure and the later Byzantine, Ayyubid, or Mamluk additions. He constructs his own category of antiquity by arguing that the complex of Baalbek was comprised of palaces built by jinns for the prophet Solomon. His aim was to resacralize greater Syria as the land of Qur'anic and biblical prophecy, perhaps—as suggested by his peculiar interpretations of other monuments and tombs like the Dome of the Rock or the tomb of Ibn ʿArabī—to counter the Ottoman government's interventions into the religious landscape of the region.Footnote 19

More specifically, I argue that Nābulusī's interpretation of Baalbek stemmed not from ignorance or obscurantism but from a flexible approach to historicity and temporality. Although he lacked the specific methods of European antiquaries and the cultural and linguistic familiarity with the Greco-Roman past, he left almost no stone unturned at the site and developed a unique visual and architectural vocabulary—borrowed from the domestic architecture of his native Damascus—to accurately describe the ruins he saw to his readers. He collected local reports and earlier writings on the site, carefully assaying their validity and discarding details he found erroneous. I suggest that he actually could have interpreted the site as Roman, as he could identify Byzantine sites and Aramaic tombstones elsewhere, but he chose to construct a different historicity, a different antiquity, for Baalbek. In other words, it is not that Nābulusī could not correctly historicize the ruins of Baalbek, but that he played with the distinctions between the different historical periods expressed in the site in order to situate it within his agenda to claim greater Syria as the land of prophecy.Footnote 20

Nābulusī's approach to antiquity recalls the “anachronic” interpretations of ancient monuments and artifacts by Renaissance scholars and artists. In the book Anachronic Renaissance, Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood argue that the story of antiquarianism, and the Renaissance at large, cannot be told solely as a progressive accumulation of knowledge about the ancient past that enabled collectors, scholars, and artists to locate ancient works ever more accurately along a linear chronology.Footnote 21 What one sees instead, at least during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is a paradoxical drive to locate old artifacts and monuments in antiquity while simultaneously recognizing that the very same objects and buildings were relatively recent constructions. Artifacts could be replicated, remade, replaced, or even reinvented while still retaining their essence of antiquity. People did this not out of ignorance or a desire to deceive, but from a purposefully flexible form of chronology that both historicized artifacts with the new tools of antiquarianism while still indexing them to a variety of other spaces and temporalities. A famous example is the baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, which was regarded as a building from Roman antiquity although it was known to have been built in the eleventh century. For Renaissance artists and scholars, the relatively recently constructed baptistery “was simply the last link in a vertical chain stretching back to Florence's pagan origins. The baptistery substituted for its own predecessors.”Footnote 22 As the authors explain in another article, “people who used artefacts in this way automatically filtered out the noise of those context-sensitive elements, concentrating instead on the essential content transmitted by the image. The result of such thinking was that a recent work had the capacity to participate in the antiquity of the prototype.”Footnote 23 Nābulusī follows the same path. He employs an antiquarian examination of the material remains, along with the tools of philology, to date the fortress of Baalbek not to the Roman past but to the time of the prophet Solomon, incorporating even recent Mamluk and Ayyubid features into his analysis. Nābulusī could look past the literal historicity of Baalbek's ruins to extract their figurative truth as a testament to the eternal holiness of Syria. He did much of the same in his grand travelogue a few years after visiting Baalbek. Perhaps not coincidently, he titled it Al-Ḥaqīqa wa'l-majāz (The literal and the figurative).

In short, Nābulusī's description of Baalbek is valuable not (only) because he demonstrates that Muslims appreciated the pre-Islamic past, but because it reveals the complexity and diversity of thinking about antiquity in the early modern Middle East. Nābulusī's vision of antiquity interprets the material past using a set of affective and intellectual tools that are parallel but variant to those used in European or Chinese antiquarianism. Moreover, Nābulusī's explorations of Baalbek point to how the religious transformations of the empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries pushed its Arab subjects to reconsider their history using material remains.Footnote 24 As in early modern Europe, there was no overarching concept of antiquity in the Ottoman Empire. When one sets Nābulusī's investigation of Baalbek alongside seventeenth-century debates over the antiquity of monasteries in Cairo, the collection of the Prophet Muhammad's relics by the imperial palace, or the arguments over the reconstruction of the Kaʿba after its destruction by a flash flood around 1630, one can begin to see the emergence of a specific tradition of antiquarianism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 25

NĀBULUSĪ AND THE ARABIC TRAVELOGUE TRADITION IN THE EARLY MODERN OTTOMAN EMPIRE

There are many ways to engage with the material remnants of human history—that is, the physical artifacts of the past as distinct from the written. These range from the usage of spolia to excavations to collections, but not all of these were as present in the early modern Middle East as they were in Europe. There is, for example, no well-attested tradition of collecting, classifying, and describing antique objects (with the notable exceptions of relics and books).Footnote 26 Illustrated depictions of ancient sites are similarly few and far between, so one must turn to a different technique of description to unearth a vocabulary of materiality: the tradition of travelogues that arose in the early modern Middle East.

While people in the early modern Middle East traveled far and wide, the travelogues they left behind depict only a small portion of that mobility. Travelogues are not incidental notes of journeys undertaken but the purposeful products of a culture of depicting travel. Yet there is no single or continuous tradition of Islamic travelogue writing. One should not imagine that every author who penned a travelogue had access to some universal library of all texts past and present.Footnote 27 The travelogues that scholars today know best—like those of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (d. 1368 or 1377) and Ibn Jubayr (d. 1217)—were largely unknown and uncited outside of the homes of their authors in the Maghreb and al-Andalus.Footnote 28 The Ottoman tradition of Arabic travelogue writing—which I estimate eventually produced two hundred to three hundred travelogues depicting the area between Damascus, Cairo, and the Hijaz, as well as the road from Syria to Istanbul—had an independent origin: it first emerged in sixteenth-century Damascus.Footnote 29

The initial purpose of Arabic travelogues in the sixteenth-century Ottoman Empire was to describe the human and physical infrastructure of the road to Istanbul. After the Arab lands were integrated into the empire in 1516–17, scholars headed to the new imperial capital to secure a position for their families or to push for diplomatic favors.Footnote 30 Travelogues were the written expression of this exchange, circulating among the inner circle of families, but also given as poetic gifts to their imperial benefactors. Rather than describing distant lands, they were essentially works of adab, a term that can be loosely translated as belles lettres. In ornate prose and verse, they depicted the constant polite exchange of poems between the heads of the religious hierarchy in Istanbul and the Damascene scions.

By the seventeenth century, however, readers and writers of these travelogues moved to expand the genre's scope, and the act of travel (and travel writing) became seen as a healthy and enjoyable practice, open to any litterateur. With the reduced availability of positions, now monopolized by key families, travelogue writers dedicated their works to friends, colleagues, and local powerholders. Some authors simply began to write about their friends or the enjoyable river next to which they sat.Footnote 31 These travelogues were still centered on the exchange of poetry, but in a much less hierarchal fashion.

ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī, our intrepid explorer of Baalbek's ruins, began experimenting with travel writing in the 1690s. His decision to travel and write travelogues was not an impulsive choice but a calculated one, made after a period of politically driven seclusion in which he devoted himself to writing deeply polemical works. He wrote in defense of a more capacious understanding of Islam, one not solely defined by its legalistic and catechistic prescriptions. He took on controversial, almost contrarian, positions in vicious socio-religious debates on the many social practices, like smoking or the medical procedure known as kayy al-ḥimmaṣa (hummus cauterization), that defined the lived religion of Islam.Footnote 32 He resisted any attempt by the Ottoman government to impose its theological or institutional prerogatives onto what he regarded as long-held traditions, and he often championed ordinary people.Footnote 33 In particular, he keenly defended the centrality of the graves of holy men, saints, and prophets as sites of worship and railed against critics of Sufism. His travelogues signaled both a retreat from the extreme polemicism of his career as a pamphleteer and a continuation, in a different form, of his intellectual and religious agenda. Modeling himself after the monumental figure of al-Ghazālī (d. 1111), Nābulusī used travel to break from his selectively antisocial seclusion and engage with fellow Muslims around the empire.Footnote 34 Unlike those of earlier travelogues, the social world he depicted did not consist of elites in Istanbul but a landscape of saints and prophets—both living and dead. This included everyone from his close friends—such as the esteemed Bakrī family in Cairo who functioned as close confidants of the governors of Egypt—to lowly villagers and those resting in obscure graves.Footnote 35

Given Nābulusī's agenda, it is not surprising that he deliberately crafted and obsessively revised his travelogues. They were more than a collection of notes and observations: he carefully chose which people and places to depict. For instance, he did not visit the Pyramids but he made sure to mention offhand that he only saw them from afar. The first two travelogues, short journeys from Damascus to Tarabulus in 1689 and to Jerusalem in 1690, were experiments in which he expanded his itinerary and ambition.Footnote 36 The third, perhaps his magnum opus, was a year-long self-reflexive odyssey evocatively titled The Literal and the Figurative that started in Damascus in 1693 and made its way through modern-day Lebanon, Palestine, Cairo, and eventually Mecca and Medina, where he performed the hajj.Footnote 37 While he often spent only a few hours drafting each of his three hundred or so works, he spent over two years crafting this one.Footnote 38 The fourth and final travelogue was a coda written in 1701.Footnote 39 He most likely had never intended to write it, but the governor of Sidon, who had presumably read and enjoyed his travelogues and company, asked him to come back to the area and write it “for the good of the common people,” and so he wrote about Baalbek for a second time.Footnote 40

The general purpose of his travelogues, especially the first one to Tarabulus and Baalbek, was to depict greater Syria (the region that today contains Syria, Lebanon, and Israel/Palestine) as a special holy land marked by the deeds and bodies of the biblical and Qur'anic prophets.Footnote 41 He was not trying to prove the literal reality of events depicted in the Qur'an (he already took for granted that the Qur'an could be used as infallible textual evidence); he wanted to resacralize the region instead. Earlier generations of Muslim scholars had accentuated the sanctity of greater Syria, particularly through pilgrimage guides and the genre known as faḍā’il, which discussed the virtues of a particular place.Footnote 42 Nābulusī builds upon this tradition but also underlines greater Syria's special connection to the prophets. Even the first travelogue's initial lines make this point clear:

He argues that Mecca and Medina are distinguished by their history of written revelation (i.e., the Qur'an), and holy men and women, saints, and companions were buried around the world, yet only Syria was “an abode of His prophets [maskanan li-ʾanbiyāʾihi].”Footnote 44 The prophets’ graves that Nābulusī visits, though, are often places of popular, local worship, like the graves of the obscure prophets Zurayq and Rayyā (said by the villagers to be prophets of Israel), a certain Aylā who was supposedly the brother of the biblical Joseph, or figures known as ʿIzz al-Dīn and al-Rāshadī, who are called “prophets of God [nabī Allah]” by the locals.Footnote 45 As will be discussed later, Nābulusī is fully aware that these shrines possess tenuous claims to historical veracity. Regarding ʿIzz al-Dīn and al-Rashādī, who are not among the prophets in Islam, he states,

Perhaps these two are [actually] noble saints. Attributing prophecy to them, and those like them in these lands, is done due to the beliefs of the majority of the villagers, who are unable to recognize saintly miracles [inkār karāmat al-walī].Footnote 46 Thus, when they see [a saintly miracle], they say, “He's a prophet,” as a learned scholar of Baalbek told us. Or it might be due to their ignorance and lack of sense. Or it might have appeared like that originally [wāridun ʿalā aṣlihi]. Only God knows.Footnote 47

Despite his apparent doubts, Nābulusī chooses to mention these various prophets in his travelogue and to pray at their graves in order to champion his populist vision of Syria's sacredness. His actions can also be seen as a response to the Ottoman government's interventions into the region's sacral landscape. This intrusion included its massive investment in the hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina that funneled hordes of pilgrims from Istanbul through the new logistical hub of Damascus, but also a variety of other architectural interventions into the Islamic monuments of the area, which often detracted from the religious significance of local shrines and holy spaces.Footnote 48 For Nābulusī, true Islam was found not in the imperial grandeur of Istanbul but among humble scholars and friends in Cairo and at local shrines of villagers in the mountains of greater Syria. His visit to the ruins of Baalbek was a key part of his vision of Islam's past and future.

MODES OF DESCRIPTION

Nābulusī visited the ruins at Baalbek twice: first on 5 September 1689, described in his initial travelogue Ḥullat al-dhahab al-ibrīz fi riḥlat Baʿlbakk wa'l-Biqāʿ al-ʿazīz (The raiment of pure gold: The journey to Baalbek and the precious Biqāʿ Valley),Footnote 49 and again eleven years later on 12 October 1700, described in his final travelogue, al-Tuḥfa al-Nāblusiyya fi'l-riḥla al-Ṭarāblusiyya (Nābulusī's gift: The journey to Trabulus).Footnote 50 Although the first description is much lengthier and more detailed than the second, he avoids unnecessary repetition in the latter. The site was not unknown to earlier writers, but never examined up close.Footnote 51 Typical are the words of Badr al-Dīn al-Ghazzī (d. 1577), a Damascene traveler, who passed through the city in 1535 and noted that “we saw a fortified castle with sturdy buildings, many tall pillars, and giant, heavy stones. Anyone who sees the stones would think they had been carved into the rock face, were it not for the shorter stones underneath. It had been one of the finest citadels, famous for its height and impregnability.”Footnote 52 Ghazzī concludes by evoking the well-known trope that “it is now in ruins [kharāb], a refuge for owls and crows.” Less commonly repeated are the much earlier remarks of the tenth-century geographer al-Masʿūdī (d. 956), who related a report that it was a “temple [haykal]” in which the Greeks held idols (specifically, those of Baʿl): “There are two great buildings, one older than the other, and inside them there are some wondrous carvings [nuqūsh] chiseled into the stone which would be difficult to do even in wood, given the height of their ceilings, the enormity of the stones, the length of the columns, the width of the openings, and the astonishing construction.”Footnote 53

Masʿūdī's source recognized Baalbek as a Greco-Roman temple but Nābulusī seems not to have had access to Masʿūdī's gigantic compilation. Instead, he carried around the geographic reference work known as Al-Mushtarik (Homonyms) by Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (d. 1229). Al-Mushtarik was a guide of geographic homonyms, or places with the same name, and Nābulusī used it repeatedly in his travels.Footnote 54 However, as there is only one place called Baalbek in the world, it was not listed in the work. Otherwise, Nābulusī also quoted often the pilgrimage guide of ʿAlī al-Harawī (d. 1215), which, as will be mentioned below, provided a few sentences on Baalbek.Footnote 55 In comparison, Nābulusī's writing easily comprises the longest and most detailed description of the site by any premodern Islamic author.

Nābulusī's description of the ruins of Baalbek occupies a significant portion of the text, but it is by no means the focus of the travelogue. He also visits a set of shrines located in minor villages. Upon entering Baalbek, he stops first at the shrine of Shaykh ʿAbdallah al-Yūnīnī (d. 1221), twice, before visiting the so-called fortress of Baalbek.Footnote 56 He sits and enjoys the pleasant river with the local pasha and friends as they recite and compose poetry.Footnote 57 Even the Turkish-speaking defterdār (finance director of the province), unable to compose poetry in Arabic, is commemorated with the inclusion of his Persian verse.Footnote 58 This is the usual rhythm of the travelogue: a constant exchange of poetry among the living and the dead. Nearly every day, Nābulusī awakens in wonderful spirits, as happy as can be. This state shifts to awe (mahāba) in the presence of certain saints or holy men. The section detailing the ruins in Baalbek takes on a very different tone, however.

In contrast to the happy contentment permeating much of the travelogue, Nābulusī reverts in Baalbek to a different affective state: wonder. Zakariyya b. Muhammad al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283), the author of one of the main Wonders of Creation texts, defines wonder as that “sense of bewilderment a person feels because of his inability to understand the cause of a thing.”Footnote 59 As in the European tradition, wonder was both an emotional state (ʿajab, taʿajjub) and the very thing that aroused such emotions (ʿajība), leading authors to investigate the natural world to understand the boundary between the natural and the supernatural.Footnote 60 Describing wonders on the road was not the main preoccupation of the genre of early modern Arabic travelogues, but wonders did occasionally find their way into the texts. Grand structures like those in Baalbek certainly evoked wonder, but so did more modest objects like lusterware ceramics.Footnote 61 In the face of this bewilderment, Nābulusī—like nearly all earlier, medieval Arab geographers and travelers when describing ancient monuments—was driven to explore the building in front of him and approach it quantitatively.Footnote 62 As he frequently did when describing other wondrous structures, he separates the complex's buildings into various components and provides numeric measurements for the dimensions of each.Footnote 63 Classifying the site as a wonder, in other words, provides him a space for a detailed and formalist examination of the site and establishes a specific epistemology of firsthand experience.

I have included below a relatively complete rendering of Nābulusī's observations, not only because they have not been previously accessible to scholars who do not know Arabic, but also to give a sense of how difficult it is to reconstruct the site today from his writings. Often Nābulusī's description comes across as repetitive and generic, and one can only make sense of his observations by constantly referring to contemporary and historical images of the site. This is the case partly because both the Roman ruins and the Arab fortress were much more intact at the time of Nābulusī's visit than they are today. A strong earthquake in 1759 severely damaged the site, and its quarried stones were used to construct the neighboring city. Furthermore, the excavation and restoration of the site in the twentieth century eliminated large parts of the staircases, cisterns, and walls that Nābulusī explored.Footnote 64

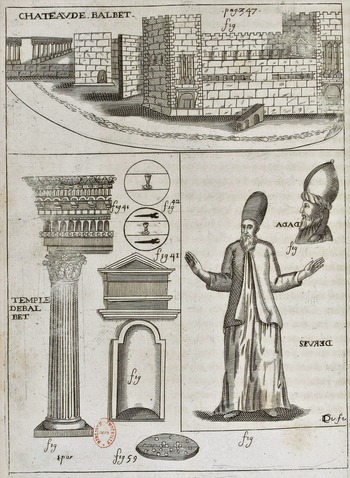

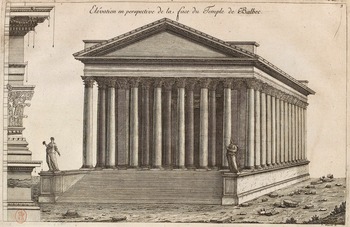

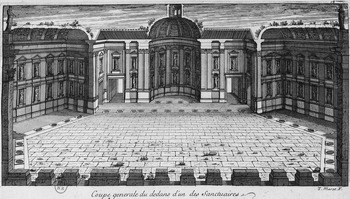

More importantly, though, the potential difficulty in understanding Nābulusī's description demonstrates how much modern readers rely on visual familiarity with Greco-Roman architecture, cultivated over the past few centuries, to make sense of what they are seeing. Engravings and later photographs were important tools in this process, and it is useful to compare Nābulusī's attempts to describe the ruins in 1689 with the first European images of Baalbek in the 1680s. These initial images of Baalbek were included in a large compilation of French architectural drawings known as Le grand Marot. Footnote 65 The engraver, the eponymous Jean Marot, never traveled to the Middle East but apparently studied the descriptions and rudimentary sketches (fig. 4), published in 1665, of Balthasar de Monconys, a traveler who visited Baalbek in 1647 in his search for hermetic and alchemical knowledge.Footnote 66 Monconys was perhaps the first to utilize the new knowledge of antiquity to recognize the Roman temples in the Baalbek complex. His interlocutors tell him about their interpretation of the site as a palace Solomon built for his queen, and the connection to Ba'al, information that mirrors the statements of Arab geographers, but Monconys dismisses this, saying, “anyone who has seen some buildings of the Romans recognizes easily that this is one of theirs and that it is very different from those that remain from the time of Solomon in Judea.”Footnote 67 Marot, in turn, translates Monconys's initial descriptions and drawings into the idiom of architectural drafting, creating a recognizable semblance of an ancient temple (figs. 5 and 6). Marot's imagining of Baalbek, however, is not actually the complex standing there: not only does it dispense with the intervening Byzantine, Ayyubid, and Mamluk layers, it overemphasizes the Greco-Roman character of the site. All three of these men—Nābulusī, Monconys, and Marot—are describing Baalbek in the initial years of its rediscovery when there were many different visions of antiquity at play. Whereas Nābulusī's vision of Baalbek as an ancient structure created by Solomon's jinns projects Qur'anic antiquity onto the site, Marot takes a similar description and projects an idealized image of Greco-Roman antiquity instead. Today Marot and Monconys's interpretation of Baalbek is privileged, but in the 1680s, this was far from a foregone conclusion. With this in mind, one can now step into Nābulusī's travelogue.

Figure 4. Depiction of the fortress at Baalbek and its identification as a Roman temple, visited by Balthasar de Monconys in 1647. In the bottom right corner are depictions of Sufi figures, a dervish and a dede (holy man or elder). Journal des voyages de M. de Monconys (1665), nonpaginated plate before page 347. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 5. Marot's imagined re-creation of the structure now known as the temple of Bacchus. Marot and Marot, fol. 139r.

Figure 6. Marot's imagined re-creation of the courtyard around the temple of Jupiter with alcoves holding statues. Marot and Marot, fol. 149r.

NĀBULUSĪ DESCRIBES BAALBEK

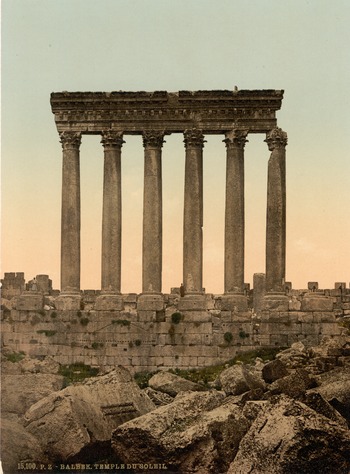

Nābulusī sets out with the pasha of Baalbek to see the town's wondrous fortress, whose beautiful towers recall “a castle in the sky [al-samāʾ dhat al-burūj]” (lit., “a sky full of towers”), and which is “one of the earliest ruins in the world [athar min āthār al-awāʾil].”Footnote 68 He briefly quotes earlier reports on Baalbek: those of locals and those of Harawī, each of which references verses of the Qur'an that they believe refer to Baalbek. Nābulusī, though, disagrees with these opinions and contends that it was a palace built by the jinns for Solomon, quoting from a different verse of the Qur'an: “And [We subjected] the wind for Solomon. Its outward journey took a month, and its return journey likewise. We made a fountain of molten brass flow for him, and some of the jinn worked under his control with his Lord's permission. If one of them deviated from Our command, We let him taste the suffering of the blazing flame. They made him whatever he wanted—palaces, statues, basins as large as water troughs, fixed cauldrons.”Footnote 69 Nābulusī describes how he entered the fortress through what seems to be its original entrance (fig. 7). Next to the gate, there was a river being used to tan hides; the tower's gate was fashioned out of a huge boulder. After passing a second gate, he notes that there is a large tower on the left and two longer colonnaded or vaulted hallways. He describes the courtyard, presumably in front of the building now identified as the temple of Jupiter, as a place “with no comparison. Arches and niches encircle the courtyard, and inside are images and statues” (fig. 8).Footnote 70 These statues do not exist today, but Marot's imagined reconstruction of Baalbek also contains them (fig. 6), suggesting that they were destroyed or removed later. Nābulusī then describes the nine pillars, today considered part of the temple of Jupiter and of which only six remain (fig. 9). He states that the pillars are around thirty cubits (dhirāʿ) (22.75 m) tall, with each pillar around thirty handspans (shibr fard) thick.Footnote 71 Above the pillars is a sturdy vaulted ceiling, and “atop these pillars is a wondrous structure, built amazingly sturdy, the length of each of its stones is five cubits long, as if the builder wanted to achieve immortality through it and be remembered forever.”Footnote 72

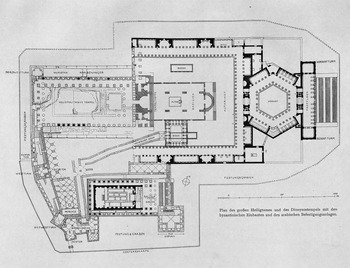

Figure 7. Layout of Baalbek complex during the Byzantine, Ayyubid, and Mamluk periods. In Kohl et al., Baalbek (1925), 1:plate 17.

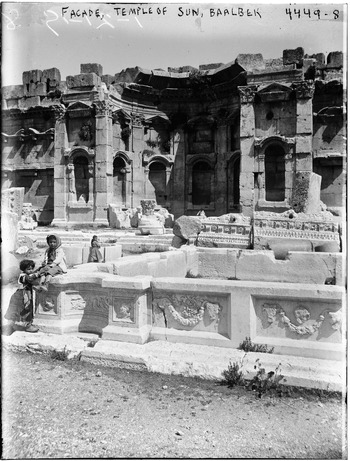

Figure 8. Courtyard of the temple of Jupiter with basins in the foreground and middle ground, and alcoves in the background, ca. 1915–20. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Bain News Service, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-25930.

Figure 9. The remaining colonnade from the temple of Jupiter at Baalbek, ca. 1890–1900. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-02648.

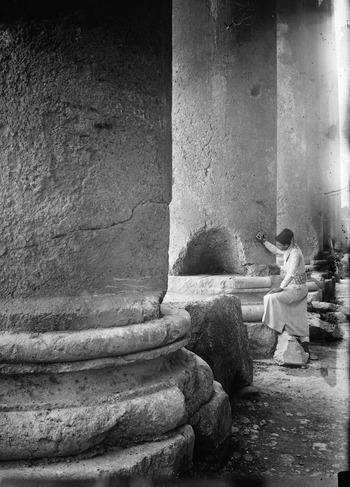

Nābulusī proceeds to discuss the remnants of the building now known as the temple of Bacchus (fig. 10). Atop fourteen pillars of similar dimensions he mentions a “great structure and a ceiling made of carved stones like a Persian ceiling [al-ṭawān al-ʿajamī], but it is an ancient building” (fig. 11).Footnote 73 His gaze moves from the foundations of the pillars made “of sculpted stone of the same size as the aforementioned foundations” to the pillars themselves, which are connected to the foundation piece by bands of copper “as thick as forearms.”Footnote 74 Interestingly, he notes that people had tried to loot the copper bands forcibly by cutting the sides of the pillar underneath them, something that later European travelers would note as well (fig. 12). He follows the pillars up to the “great edifice” of stones “even bigger than the foundation stones, geometrically arranged in a straight line [muhandasa ʿalā haʾya mustaqīma].”Footnote 75 He mentions that a number of people there had told him that once a man had climbed to the top of the edifice above the pillars and found a giant hammer (shāqūf) made of iron whose weight was “eighty Baalbek raṭl, which is one and a half times a Damascus raṭl” (1.85 kg), which would make the hammer around 222 kg. From the roof of the edifice, he turns his attention back down to the ground where he notices a giant foundation stone, “a single piece five cubits long and five wide” that was “as though it had been atop one of the pillars and fallen to the ground, but had failed to damage the vaulted foundation [qabu] of the fortress beneath it.”Footnote 76

Figure 10. The remnants of the temple of Bacchus, ca. 1890–1900. The structure atop the temple on the left is a remnant of the tower that has now been removed. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-02643.

Figure 11: The ceiling of the peristyle of the temple of Bacchus, likely what Nābulusī referred to as a “Persian ceiling [al-tạwān al-ʿajamī].” Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-matpc-02861.

Figure 12. Pillars in the temple of Bacchus that have been cut away to remove metal. Photograph from ca. 1900–20. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-matpc-05204.

Nābulusī then moves on to describe a “large, wide, and tall tower.”Footnote 77 The tower or building is not extant,Footnote 78 but it was built on the southeastern steps of the temple of Bacchus, conjoined to the temple itself (fig. 13), and nineteenth-century photographs show a small part of the remaining fortification, idling above the temple's columns (fig. 10). He situates the tower within a shabbāk (perhaps a latticework of stones or wells), mentioning that the tower is encompassed “on all sides with niches that are filled with images and statues [ṣuwar wa-tamāthīl].”Footnote 79 He goes inside the tower and notes a large column into which a spiral staircase had been carved. He ascends the stairs to the roof where he examines the complex's vista, and sees in the distance the grave of Shaykh ʿAbdallah al-Yūnīnī, whose grave he had visited twice before entering the fortress of Baalbek, pointing out that the saint's aura was visible even from the fort, “as if his light was a distant star.”Footnote 80 He then moves back down the tower, describing the seven dark rooms (qāʿāt muẓallamāt) that could only be explored with candles and lamps. One of the rooms was apparently flooded with standing water and Nābulusī is informed by one of the people there that the water is stored (marṣūd) for when the gates of the fortress are closed, so as to create a flow of water from the walls to the outside. He then mentions a certain well there called the biʾr al-ṣayyāh, or the Wailers’ Well, that Ibn Maʿan (d. 1635), the Druze warlord who held the fortress a few decades prior, had sealed when he destroyed the fortress. The marvel of the well was that water only appeared when the fortress was besieged; the longer the siege, the more water.Footnote 81

Figure 13. A reconstruction of the temple of Bacchus once it had been converted into a citadel. In Kohl et al., Baalbek (1925), 3:plate 2.

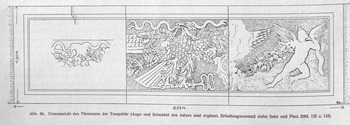

At this point, Nābulusī ventures back outside, where he describes for the first time a figurative image located on the underside of the roof of the tower (burj) (fig. 14): “an image of a serpent and a scorpion with an image of two of them opening their mouths as well as an image of a drum and a reed flute in the form of the two of them being played” (fig. 15).Footnote 82 He then makes it clear, to the modern reader, that he is describing a marble relief as he mentions that “all of this is carved on hard white stone; the gaze lingers on it in amazement,” and he mentions that there are more reliefs of human figures in the vaulted hallways leading to the fortress.Footnote 83 These images are hard to place today, but the placement of the figure of the serpent provides a hint. He is most likely looking at the keystone on the underside of the lintel over the gate to the adytum of the temple of Bacchus, which today we recognize as a relief of “an eagle with a caduceus [a herald's staff] in his claws, holding a garland in his beak” (fig. 16).Footnote 84 Viewing the relief from twenty meters below, Nābulusī interpreted part of the undulating garland as a serpent enacting a chronological sequence of scenes. On the side, the garland is being held aloft by winged genii, but Nābulusī does not mention them. He might have parsed the eagle's feet and caduceus as a drum and a flute. The description makes clear that the tower structure Nābulusī was exploring was merged with the now independent temple of Bacchus.

Figure 14. Portico of the temple of Bacchus, ca. 1870–85. On its underside is the marble relief that Nābulusī observed. Félix Bonfils. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-68727.

Figure 15. Detail of the marble relief on the underside of the portico of the temple of Bacchus, 2010. Photograph by Guillaume Piolle.

Figure 16. Drawn reconstruction of the marble relief on the underside of the portico of the temple of Bacchus. In Kohl et al., Baalbek (1925), 2:22.

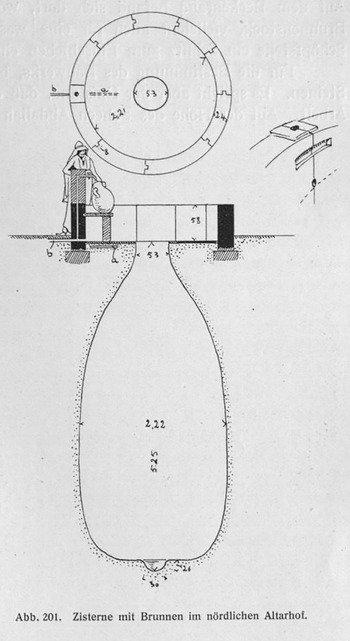

Nābulusī then moves on to describe other buildings and features of the fortress that seem difficult to place nowadays, though are most likely part of the fortifications built on the western wall. He mentions another tower (burj) with a roof in the form of a room (qāʿa) (fig. 10); within it is a “bramble net [qafāʿih],”Footnote 85 presumably for catching birds, and in the middle of the tower are two īwāns (large vaulted halls open on one side) that each faced beautiful domes. In one of the domes is a long set of stairs that was said to imprison those who had committed frightful crimes. Outside the gate of the tower is a wide staircase of approximately forty steps that goes up to the top of the tower, and below this another tower accessed by another staircase of forty steps. Here he takes time to appreciate the aesthetics of the “plaited stones [hijāra mushtabaka]” between the steps and the two īwāns and four alcoves (qubba) made of “select carved stone.”Footnote 86 He moves back into the main courtyard of the fortress, describing a large well of water without any bottom that confounds those that see it.Footnote 87 In the courtyard is a large pool (baḥra) made entirely of one piece of stone, its sides buried underground (figs. 8 and 17).

Figure 17. Reconstruction of the cistern/basin in the grand courtyard that Nābulusī interpreted as proof of Baalbek's construction by jinns. In Kohl et al., Baalbek (1925), 2:143.

Finally, Nābulusī moves toward the wall of the fortress, mentioning that outside the wall is a solitary pillar that is said to mark the height of the water by the fortress, but it was in a ruined state.Footnote 88 In the southern (qiblī) wall of the fortress were forty stores (ḥānūt) built of stone, said to have held merchants’ goods in the ancient times, when the area was a market.Footnote 89 He then turns to describing a row of three giant stones in the wall (midmāk), each of which is eighty-five qadam (feet) long and thirty-five qadam tall.Footnote 90 Here he is describing what is now known as the Trilithon, gigantic stones weighing around 1,000 tons each, that formed the podium wall of the temple of Jupiter, and would have been incorporated into the western wall of the fortress.Footnote 91 He then moves his gaze beyond the wall, to the graveyard and to a large nearby excavation (ḥufra), today recognized as the quarry, in which lies a stone the same size as those of the Trilithon, despite not having fallen from anywhere. He mentions that the common people call it ḥajar al-ḥibla (stone of the pregnant woman) (fig. 18), and another giant rounded stone next to it is known as al-mighzal (spindle).Footnote 92 Nābulusī then points out that the fortress once had giant gates, said to be the original gates: one on the west side, presently blocked, and another that led to the aforementioned tannery. Nābulusī finally mentions that the fortress was previously inhabited (ʿāmira maskūna), and that he met some people who remembered it before it was ruined and who claimed that it was destroyed by Ibn Maʿan in his bitter feud and battles with the Banī Ḥarfūsh in 1623.Footnote 93

Figure 18. The Stone of the Pregnant Woman, ca. 1890–1900. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-02651.

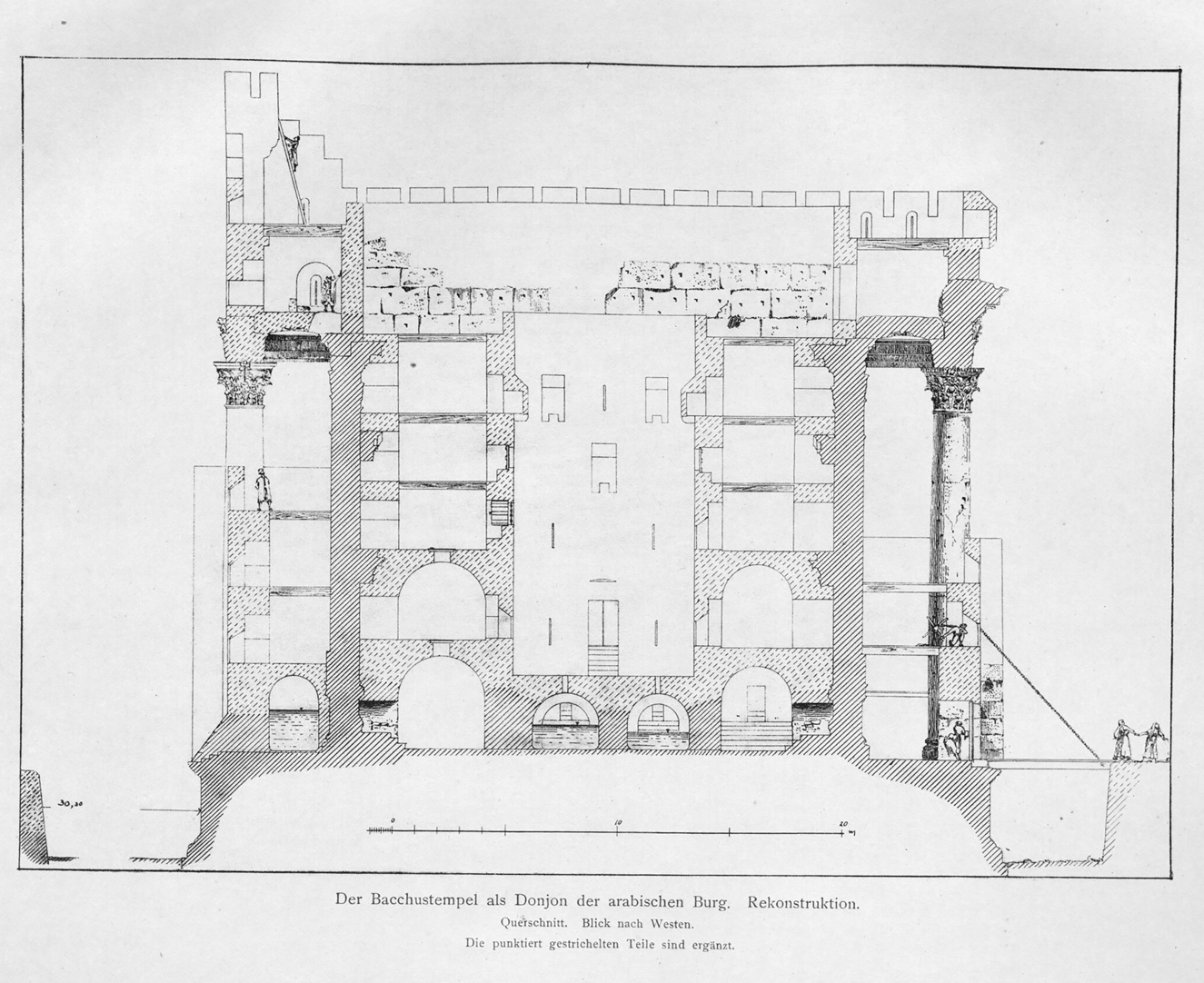

When Nābulusī visits Baalbek again eleven years later, his description, which is recorded in his fourth and final travelogue, is curtailed. He still places the site squarely within the framework of wonder—“we headed toward the wondrous fortress and those unique buildings and saw there one of the wonders of history and marvels of creation”—but he does not repeat himself much.Footnote 94 He only describes in more detail the building now known as the temple of Bacchus. He first mentions that “one of the most wondrous things we saw was a ceiling [ṭawān] made of great stones, that were pierced and hollowed [mukharram mujawwaf], erected over columns that join a wall of the fortress.”Footnote 95 Here, he seems to be describing the temple of Bacchus again, talking about the measurement of its ceiling and the amazing diameter of its pillars. He notes that the pillars are in three pieces, not including the foundation piece (qāʿida) that is buried underground, that the middle segment of each pillar is hollow and contains a column of copper, and that each segment of the pillar is placed atop the other. He then mentions that some people had previously extracted one of these (internal copper) poles and that its weight was fifteen raṭl shāmī (30 kg). Nābulusī then provides a total count of the columns—thirty-six—for the external set of pillars and speculates as to the location of a door between one “distinguished [mashraf]” (read, fluted) pillar and another partially remaining pillar.Footnote 96 He then enters the interior of the temple (fig. 14) via a “small, raised door” at the top of a stone staircase.Footnote 97 The interior of the temple has twenty-two columns, each fluted like the ones in the front of the temple.Footnote 98 He then begins exploring the two great well-like structures (ʿuḍaḍatān) that led to the roof. Each had a long spiral staircase, now accessible only to small and slender people through a small window. He reports that once, before the stairwells were destroyed and blocked, they led further underground, but are now flooded. Nābulusī is likely referring to fortifications and cisterns (fig. 13), now removed, that were built onto the floor and vault of the temple of Bacchus. He even marvels at the ninety remaining steps, blocked long ago when the roof collapsed onto them.Footnote 99

NĀBULUSĪ INTERPRETS BAALBEK

Today, with the benefit of centuries of scholarship on Baalbek, elements of Nābulusī's description can be matched to the Roman temples of Bacchus and Jupiter. Nābulusī, however, believed Baalbek to be the wondrous ancient ruins of a complex built by jinns for Solomon. At first glance, it is easy to dismiss this as the misinterpretation of a man echoing local legends. Yet he purposefully argues for this conclusion after careful observation of the site and incorporates a wide range of evidence, like the waterworks that European travelers dismissed out of hand. More importantly, he insists that this is no ordinary if fabled castle, but an “ancient [qadīm]” building. Nābulusī is using Baalbek to create a category of “antiquity,” albeit one whose classificatory and affective schema fall on different lines than the ones that developed around the Greco-Roman past in early modern Europe. To understand Nābulusī's thinking, one has to delve a bit deeper into his interpretation of the site.

Let me first turn to Nābulusī's choice to identify Baalbek as the site of Solomon's palace built by jinns. The prophet Solomon had long been a prominent figure in the larger Islamic tradition.Footnote 100 Much of his reputation rests on the late antique Jewish-Christian and Hellenstic lore that casts him as an all-knowing and perfect king, who possessed such a command of magic and astrology that he could order demons to build the Temple for him.Footnote 101 The Qur'an mirrors these late antique ideas about Solomon stating that jinns were forced to labor for him, building “whatever he wanted—palaces, statues, basins as large as water troughs, fixed cauldrons.”Footnote 102 Many different ancient structures around the Middle East were associated with Solomon's fantastical buildings, including the fortress of Baalbek.Footnote 103 Even Nābulusī notes, by way of making a counterclaim, that Harawī's pilgrimage guide states that the people of Persia claim that “Dahhak is Solomon, son of David, . . . and that the jinns erected . . . for him . . . the ruined stone structures in the district of Istakhar in the lands of Persia [i.e., Persepolis].”Footnote 104 Thus, it is not surprising to hear that Balthasar de Monconys states that locals told him in 1647, a bit over forty years before Nābulusī arrived in Baalbek, that the temple/fortress had been one of Solomon's palaces, built for Queen Sheba. The famous Ottoman traveler Evliyā Çelebi, on his short stop in Baalbek in 1649, also insists that the “fortress” was constructed by Solomon's enslaved demons.Footnote 105

In the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a new fixation with Solomon as the image of an ideal king seems to have taken hold, especially in the Perso-Turkic world. For example, he began to appear on the frontispieces of the Shāhnāma (The book of kings), a seminal Persian work that not only introduced the ancient Iranian legends in which kings were the progenitors and drivers of civilization, but whose illustrations became a space in which the concept of kingship itself was expressed.Footnote 106 The Ottoman sultan Süleyman (r. 1520–66) was especially keen in depicting himself as the second coming of Solomon.Footnote 107 It is not surprising then that when the imperial architects set out to build Süleyman's mosque in Istanbul, they scoured the Middle East in order to collect red granite columns from sites rumored to be Solomon's ancient palaces in order to create an edifice that could rival even the antiquity of Hagia Sophia. They brought columns from Constantinople itself, Alexandria, Cyzicus, and Baalbek, and even the workers transporting and erecting the columns were described as laboring like Solomon's demons (dīv).Footnote 108 By arguing that Baalbek was the work of Solomon's jinns, Nābulusī was not making a novel claim about Baalbek's origins but proving that Baalbek—rather than Constantinople or Persepolis—was the one and only site of Solomon's temples and that greater Syria was the stomping grounds of the prophets.Footnote 109

For Nābulusī, proving Baalbek's antiquity required demonstrating that it was not built by humans. This is why he actively dismisses the locals’ interpretation, and that of Harawī's guidebook, that Baalbek was the product of the people of Thamūd who “hewed through the rock,” according to the Qur'an.Footnote 110 Nābulusī rejects this historicization because, “it is clearly attested to by the senses that humans could not have built these gigantic structures.”Footnote 111 The site confirms a different verse of the Qur'an that describes the fountains, “palaces, statues, and basins as large as water troughs,” built by the jinns for Solomon.Footnote 112 After explaining to the reader that jifān is the plural of jafna, and means a large bowl, and that jawābī is the plural of jābiya, and it means a big pool, Nābulusī states, “We truly saw these astonishing structures in the fortress of Baalbek and the ornate palaces, the various statues, the great pillars, and gigantic stones. And we said that maybe this verse refers to this structure that confounds the mind and imprints [tashakhkhus] itself on the eyes of man.”Footnote 113

To prove his conception of antiquity he sets out to observe as closely as possible the ruins of Baalbek. The first thing he describes are the “palaces,” those structures now identified as the temples of Bacchus and Jupiter. He seems particularly astounded by the structures atop the columns, what is now regarded as the entablatures of the temples and part of the later fortifications. He notes that their blocks seem to be as large as those at the foundations, and in some places these blocks have fallen on the ground. This might seem like a minor detail, but it suggests that Nābulusī imagined the palace of Solomon as a building that once stood atop the columns, a “castle in the sky,” and not the temple structure itself—as if a second building was placed upon the stilt-like marble columns of a Greco-Roman temple and all that remained was its foundations.Footnote 114 This is why Nābulusī recalls the story of one local who claimed that a huge hammer was found on top of the entablature rather than on the ground level; the hammer was so heavy that presumably only jinns could wield it when constructing the palace. To us, habituated to the image of a Greco-Roman temple, this vision might seem a bit counterintuitive, but this is also how earlier geographers like Ḥamawī, whose works Nābulusī possibly read, described the temple at Baalbek: “palaces upon marble columns.”Footnote 115

There were other parts of Baalbek that Nābulusī described in meticulous detail but that never garnered the attention of European travelers. Take, for example, the deep cisterns (figs. 8 and 17) and the giant basins he mentions. Both European travelers and archaeologists regarded them as later Byzantine and Arab additions, and they were eventually removed in the course of restoration. Nābulusī, however, considered these water features to be key pieces of evidence for his theory of Baalbek: the bottomless basins were the very same ones that the jinns built as mentioned in the Qur'an. The statues (fig. 6), which seem to have disappeared by the eighteenth or nineteenth century, were just like those built by the jinns. To find them all, he had to explore every possible part of the site, sometimes with oil lamp and candle in hand, insisting that “this description of ours about [Baalbek] was [based] partly on observation [muʿāyina] and partly on reporting [ikhbār] from someone originally from Baalbek who repeatedly entered it as a child and as an adult and who has a comprehensive knowledge of the site from excellent and trustworthy sources [min al-thiqāt al-akhyār].”Footnote 116

Nābulusī's technical vocabulary—which is drawn heavily from the domestic architecture of Damascus—initially seems too limited to describe the subtleties of ancient buildings.Footnote 117 In the first half or so, it is possible to follow his description because it can be matched to extant temples. In the second part though, it becomes much harder as his use of vaults (qabu) and rooms (qāʿa) is too generic. It is unclear what he means by a shabbāk (a latticework of niches?) or a qafāʿih (a bramble net?). When he seems to be describing fluted columns, he calls them mashraf, which can perhaps be translated as “distinguished.” Especially in regard to figurative representations, as in the example of his description of marble reliefs, it can be difficult to make his words match the images in our heads. Yet his vocabulary also possesses a good deal of observational finesse. Take, for example, his description of the ceiling in the temple of Bacchus (fig. 11) as a “Persian ceiling [al-ṭawān al-ʿajamī].” At first, it seems that he is suggesting a family resemblance to some sort of decorative geometrical pattern, but a “Persian [ʿajamī]” ceiling in the seventeenth century referred to woodwork decorated in low gesso relief (pastiglia) (fig. 19), as opposed to the flat, painted, silken (ḥarīrī) decorations.Footnote 118 Nābulusī was personally familiar with Persian ceilings as his boyhood home contained a prime example of one.Footnote 119 Just in case the reader thinks Nābulusī is describing something modern, he insists that it is an “ancient building [abniya qadīma].”Footnote 120 The word choice makes sense if one thinks of Nābulusī describing not an ancient temple but an ancient palace with halls, rooms, wells, and decorated walls and ceilings.

Figure 19. Ceiling of a Damascus room displaying the ʿajamī (Persian) technique of carved and painted gesso relief on wooden panels, 1709. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of The Hagop Kevorkian Fund, 1970, accession no. 1970.170.

Nābulusī seems so intent on proving that Baalbek was constructed by jinns in antiquity that he even dismisses suggestions that humans were responsible for its destruction. When the locals tell him that the fortress was inhabited until it was destroyed by Ibn Maʿan in his battles with the Banī Ḥarfūsh in 1623, he brushes them aside, saying that “it is clear that its destruction was earlier, around the year 597 [1201],” and then quotes at length Abu Shāma's al-Dhayl ʿalā al-rawḍatayn (Supplement to “The two gardens”) regarding a massive earthquake that wreaked destruction throughout the Levant: “And the people abandoned Baalbek, [surviving by] picking gooseberries on Mt. Lebanon, where mountain men fell upon them and they all died. And the fortress of Baalbek, with is great stones and strong build was ruined.”Footnote 121 Only nonhuman forces like an earthquake, in other words, could be responsible for the site's destruction. Satisfied with his work, Nābulusī ends his description with the words, “In sum, it is a grand fortress, and its buildings are wondrous and amazing, which proves that these are ancient ruins [āthār qadīma].” He dispenses with the customary invocation “only God truly knows [Allahu aʿlam]” that he and all authors added when in doubt and encapsulates the description with two lines of verse:

Convinced of its nonhuman origins, Nābulusī places it squarely in the ancient and prophetic landscape of Syria.

AN ANTIQUARIAN APPROACH TO EVIDENCE

One could end Nābulusī's story on the above note: a seventeenth-century scholar who, despite his meticulous observations, comes to the misguided conclusion that Baalbek was built by jinns at the command of the prophet Solomon. I think, however, that the story can be complicated a bit further by examining Nābulusī's interpretation of material evidence at a variety of other sites. What emerges is a portrait of a scholar who, despite being quite aware of the Greco-Roman and Arab past, decides not to integrate it into his category of antiquity.

First, should one be so quick to assume that Nābulusī completely failed to notice evidence that the site was constructed by humans, whether of the Roman variety or otherwise, given that he prided himself on his detailed examination and description of Baalbek? Was he so culturally unaware of Greco-Roman antiquity that he was unable to suggest even a tenuous connection, for instance, linking the many statues and reliefs that lined the sides of the former basilica with Christians and their idols? The answer, I suggest, is no.

As mentioned earlier, a few medieval geographers like Masʿūdī did refer to Baalbek as a set of Greco-Roman temples. Even if Nābulusī had no access to the heavy tomes of Masʿūdī's encyclopedia, it is clear from his travelogues that he did know of the Greco-Roman and Christian past of the region. He contemplates that a certain Mount Zion (Jabal Ṣahyūn) on the Lebanese coast is “called after the name the Romans gave it when they resided here in earlier times.”Footnote 123 Outside of Tarabulus, he passes an old aqueduct (qanāṭir), about which he composes a nice little poem, and then quotes an early seventeenth-century travelogue by the Damascene scholar Ḥasan al-Būrīnī (d. 1615) about how the aqueduct was built by al-Brins, one of the former Christian kings in the environs of Tarabulus.Footnote 124

Equally striking is Nābulusī's omission of one site in particular in the current-day Baalbek complex: the temple of Venus (fig. 20). At the time of Nābulusī's visit, the temple was apparently being used as a church by the town's significant Maronite Christian population.Footnote 125 It was just outside the walls of Baalbek's fortress, but it was frequented by all the European visitors to Baalbek. The town's Christians in turn received many European visitors and were engaged enough with European debates that in 1673 the bishop of Baalbek signed a statement denouncing Calvinism at the request of the patriarch in Antioch.Footnote 126 On top of this, the pasha of Baalbek frequently hosted, accompanied, and supported the antiquarian endeavors of European visitors to Baalbek.Footnote 127 Even if Nābulusī never engaged with any Christians (though later in life he would coauthor a book with the Maronite patriarch),Footnote 128 he toured Baalbek and its environs with the pasha and his entourage and one imagines that they would point out those places that drew the interest of other travelers—such as the Latin inscriptions throughout the site.Footnote 129 Moreover, as mentioned above, he also relied on local informants, who might have directed his attention to the temple.

Figure 20. Remnant of the temple of Venus, ca. 1870–80. Félix Bonfils. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, object no. 84.XP.709.748. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Even more difficult to explain than Nābulusī's disregard of Baalbek's Roman past is his omission of the site's Arab past. There were numerous Arabic inscriptions in the site from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, detailing the building and renovation of the moats, walls, fountains, and mosques ordered by the Ayyubid and Mamluk rulers.Footnote 130 Given that Nābulusī interpreted the site as a single product of the jinns of Solomon, who in particular produced the fountains and reservoirs, it is striking that he ignored these inscriptions. Elsewhere he is an astute observer of epigraphic evidence, noting bits of poetry scrawled as graffiti in tombs, inscriptions left by former patrons, and inscriptions naming the builders of long-abandoned cities.Footnote 131 When one looks at Nābulusī's examination of inscriptions in his later travelogue one finds that he does note non-Arabic pieces of evidence. In his third and largest travelogue, The Literal and the Figurative, he visits the grave of the famous companion of the Prophet, Kaʿb al-Aḥbār, in Damascus, a site of pilgrimage located outside of a small mosque. Nābulusī notes that on the grave is “a chronogram [tārīkh] written in Hebrew or Syriac.”Footnote 132 This seems to inspire a moment of doubt in Nābulusī, who at this point in the travelogue is quite intent on verifying the literal reality of graves. He scours the biographies and other reports on Kaʿb al-Aḥbār to establish whether or not this was his grave, only to return with inconclusive evidence.

The absence of any mention of Baalbek's Greco-Roman and Arab origins suggests not so much ignorance on the part of Nābulusī but a purposeful interpretative stance. He insists on reading Baalbek as the work of Solomon and his jinns because his aim was to cast greater Syria as a primeval holy land replete with the tombs and cities of ancient prophets. He operated much like the antiquarian artists and scholars detailed in Nagel and Wood's Anachronic Renaissance, who sought out and idealized antique artifacts but also “automatically filtered out the noise of those context-sensitive elements, concentrating instead on the essential content transmitted by the image.”Footnote 133 As an antiquarian, Nābulusī sets out to objectively observe and contextualize every feature of Baalbek he could find in order to locate it in antiquity. His vision of antiquity, however, was rooted in the Qur'anic and biblical past. The various reinventions and renovations of Baalbek, whether as a Roman temple or a Mamluk castle, were simply layers of historical varnish obscuring Baalbek's core identity as a palace built for Solomon. It is not that Nābulusī did not recognize these layers of history, he simply chose to focus on what he regarded to be its essence, much in the same way that European travelers and archaeologists would look past Baalbek's Arab or Byzantine past to focus on the Roman temple.

The same approach can be seen even more clearly in his other encounters with monuments during his travels in which he often rejects the material evidence at a site to focus on its inherent essence. In a telling example on 25 September 1693, Nābulusī narrates an intellectual conversion of sorts that occurs when he is forced off course and into a small village, Minya, in the countryside near Tarabulus. He is pleasantly surprised to find that the village has the grave of the prophet Joshua (Yūshaʿ). However, when he approaches the grave, he reads a stone inscription that clearly states, “This is the grave of the humble servant Shaykh Yūshaʿ, erected by the Sulṭān al-Mālik al-Muqtafī al-Ṣāliḥī in Tarabulus in the year 684 [1285–86].”Footnote 134 More damning than the date, which could have referred to the most recent construction of the tomb, is the fact that this Joshua was referred to as “Shaykh” instead of “Prophet.” Here Nābulusī, who had spent the preceding days chiding villagers for praying at tombs that did not concur with textual sources, is forced to confront directly the contradiction between his own personal perception of the grave as full of “awe” and the textual reality in front of him. After consulting a variety of books and finding no evidence that the Prophet Joshua was buried in the village except for what was told to him by the villagers, he ultimately chooses to believe his own perception of the grave as that of a prophet, attributing the faulty inscription to the fact that the scribe did not know the proper titles for prophets.Footnote 135 He abandons his authenticating stance and begins to renarrate his own life, interpreting his arrival in the village as a reenactment of the miracle of the Joshua—the delay of sunset for an hour as the Israelites invaded Jericho on the Sabbath eve.Footnote 136

This is, in a sense, similar to the proof he employs in his second travelogue on 11 April 1690 when he declares that the dome in the Dome of the Rock was built by the nefarious Franks—that is, the Crusaders—to obscure the miraculous boulder that he believed hovered above the ground. As Samer Akkach notes in his study of this episode, Nābulusī is familiar with the evidence that the Dome of the Rock was actually built by the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685–705). Moreover, the Dome of the Rock had been renovated by the Ottoman sultan Süleyman over a century prior.Footnote 137 Yet Nābulusī practices a “selective historical amnesia,” as Akkach puts it.Footnote 138 He constructs a different historicity of the site to underline the rock's essential, pre-Islamic holiness, before the interventions of the Umayyads or the Ottomans.Footnote 139 Another example can be seen in his claim that the tomb of the famous Sufi theorist and saint, Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240), originally built by Sultan Selim (r. 1512–20) after he conquered Damascus, was in the wrong location and that those who worshipped there were approaching Islam in the wrong manner.Footnote 140 On that note, let me return once more to Nābulusī's examination of the tombs of greater Syria. On 23 October 1693 he visited a village named Mashhad al-Nabī Yūnus (Tomb of the prophet Jonah), near Safad, named after Jonah's supposed resting place. Nābulusī realizes that the same tomb exists in many different places and is most certainly false.Footnote 141 He decides, however, that “in any case, the location is ascribed and set down, and the people of the village must be respected,” and then quotes the famous hadith that “deeds are considered only by their intention.”Footnote 142

These episodes reveal the multiple commitments of Nābulusī's interpretative stance. He was intent on discovering the ancient sacral landscape of Syria and matching every monument with any textual and material sources that attested to their antiquity. Yet, when faced with a site that was not corroborated by the evidence at hand, he was always able to look beyond its literal value and focus instead on its essential and figurative truth, as he would have it. This process of finding a site's historical essence worked both ways; he accepted certain graves and sites while rejecting others. Yet, even here he maintained an agenda: he was always inclined to privilege the tenuous claims of commoners about a prophet's grave in their village and dismissed the historical veracity of grand edifices built by sultans.

CONCLUSION

ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī's travelogues were far from the random recollections of a dilettantish traveler. He developed within them an astute, and intellectually flexible, method of locating monuments and artifacts in antiquity. Employing copious firsthand observations and utilizing the reports of locals, he demonstrated that the ruins of Baalbek were a palace the jinns built for Solomon and that greater Syria was a land of prophecy. As I suggested, Nābulusī himself was capable of reading the site as a Roman temple, much like the other travelers from England and France that came to Baalbek. Nābulusī's notion of antiquity, however, was anchored in the Qur'anic past rather than in the Greco-Roman one that animated the antiquarian project in early modern Europe.

Nābulusī's travelogues were well regarded and widely read, but they do not seem to have inspired others to adopt his concept of antiquity or his method of antiquarianism.Footnote 143 Nor did his conclusions become part of a connected history of eighteenth-century antiquarian knowledge that eventually informed modern Western understandings of Baalbek. Nābulusī's investigation instead provides a glimpse into one instance of an Ottoman antiquarianism—Ottoman not because it reflects some generic mentality that all the empire's subjects possessed, but because Nābulusī's intellectual and religious project emerged from the intersecting forces that the empire had set into motion. He emphasized greater Syria's unique sanctity as the land of prophecy, with a history that stretched far into pre-Islamic times, thus legitimizing local visions of religiosity. As a result, this project often countered the Ottoman government's interventions in the sacral landscape of the region, or responded to broader debates across the empire.

Scholars interested in unearthing Middle Eastern antiquarianisms should aim not simply to highlight those moments when pre-Islamic antiquity was valued, but to understand how and why premodern Middle Easterners investigated the material remnants of their ancient past. What work did the concept of antiquity do for them? Antiquity must be conceived more broadly than just those traditional civilizations whose ruins now litter the Middle East—i.e., the Greeks, Romans, Hittites, ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, etc. It is important to note that although Nābulusī provides modern readers with one of the longest descriptions of a Roman temple by a premodern Islamic author, he never cared to view the ruins of Baalbek as Roman. He regarded them instead as Qur'anic remnants, as it were, a type of antiquity that falls outside our current definitions. In other words, rather than predefining antiquity, one should be attuned to the many different visions of antiquity and traditions of antiquarianism that existed in the early modern Middle East, just as scholars have done for the rest of the world.

Of course, looking at Nābulusī's conclusions from the viewpoint of contemporary archaeology, it is easy to dismiss his writings as historically inaccurate and to privilege the conclusions of his Western contemporaries. Yet, even in the second half of the seventeenth century, the identity of Baalbek as a Roman temple was far from certain. European interpretations of Baalbek tended to overemphasize its Greco-Roman past as much as Nābulusī overstated its biblical and Qur'anic origins. Rather than measuring his approach against some idealized image of modernity, one should compare it to that of his (slightly earlier) contemporaries in Europe: Nābulusī's elastic approach to historicity, temporality, and the interpretation of evidence was not so different from the antiquarian project of the Renaissance.