Robbins Burling's impassioned and thoughtful argument for a new English orthography is a two-pronged attack on the stubborn oddities and complexities of Modern English. Burling establishes pathos by connecting his arguments with his own personal narrative as a struggling speller in childhood. Clearly a bright student, Burling was vexed at nearly every stage of his schooling by his own awful spelling and the derision of a few stubborn authority figures. This deeply felt personal struggle imbues his arguments with a certain urgency and emotional appeal; ‘children cannot influence educational policy, but for the sake of their children and grandchildren, adults ought to be willing to support reform’ (p. 7). But the appeal he makes is not merely an emotional one. Oddity after orthographic oddity is delineated in order to buttress his claim that English spelling is not merely a nuisance, but rather a crippling hindrance to the literacy and well-being of countless people - principally children. In fact, he states unequivocally that, ‘English orthography seems, consistently and seriously, to retard the acquisition of literacy’ (p. 22).

Indeed, but how to reform the behemoth that is Modern English? There are simply too many speakers, too many accents, too many authorities, and the impossible tasks of both agreeing upon a reformed orthography, and the need for such an orthography.

To begin, Burling does the foundational work of outlining the history of our ‘chaotic spelling’ (p. 18) and the many successes and failures (mostly failures) that have colored the evolution of the English tongue. Part 1 is organized under this rubric and is used to establish the need for reform. He makes effective use of great writers and thinkers who have lamented either their own inadequacies as spellers, or the sad state of spelling in general: Benjamin Franklin, A. A. Milne, Andrew Carnegie and George Bernard Shaw, to name just a few of this wide-ranging group. [Intriguingly, the author takes a swipe at Noam Chomsky in his closing chapter. Chomsky's assertion (Reference Chomsky and Halle1968) that English orthography is ‘close to optimal’ (p. 147) is particularly repellent to Burling.]

Burling's account of the repeated failure of spelling reform is perhaps best captured in his re-telling of the career of Noah Webster, the first great American lexicographer. Webster advocated for radical changes to the perplexing spelling rules of English, yet he was financially dependent upon the sales of his widely used school books. This required him to compromise when he published his eponymous dictionary. This compromise considerably weakened his radical streak and by the end of his career, he appeared to have surrendered to the forces of linguistic history. As Burling carefully outlines, Webster's spelling reform efforts amounted to little more than the paltry American/British spelling distinctions such as o/ou in color/colour and er/re in theater/theatre.

Burling continues by specifying exactly what needs fixing in English. This assorted set of problems includes: homophones, deer/dear, the French ‘c’ for an ‘s’ sound as in mice, and the profusion of modern acronyms and other linguistic strangeness such as NATO, CERN, and PayPal, which have begun to function as word units themselves. As a backdrop to this index of difficulties, Burling unwinds the tale of English's evolution from Anglo-Saxon to present day. The familiar story of the myriad influences - the Norman Conquest, Renaissance reforms, and clumsy scribes – is crisply recounted by Burling. Throughout, his re-telling is punctuated by a conviction that it need not have been this way. Indeed, in Burling's hands, it is easy for the reader to re-imagine the history of English unfolding in a vastly different way, with only a handful of historical variables altered.

The counterclaim which Burling most often addresses, as he champions spelling reform, is the diminished access to classic texts. He leans upon Shakespeare and Chaucer here, and he argues effectively that these texts would lose no value if only the spelling were changed. Indeed, the spellings in these works have already been significantly modernized from their original form, with no loss of value.

Non-English language reform endeavors are presented by Burling as well. Norway, Germany, and Yugoslavia, have all undertaken such tasks, yet Burling seems most impressed with the reforms in Korea and Turkey. The revamping of Korean orthography took centuries and required a parallel reform alphabet which eventually displaced its predecessor. The Turkish reforms, undertaken by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, coincided with the massive historical forces of revolution in the Near East, and world war, and they present the only modern example of immediate, and total orthographical reform.

The historical progress made in English, is meager in comparison. The International Teaching Alphabet, the phonetic renderings in dictionaries (surprisingly not standardized), and secretarial shorthand, can be counted as successful forays into improving of our ‘tangled’ orthography (p. 7), however, their impact has been negligible. Finally, Burling surrenders, and concludes Part 1 with, ‘what we need now is not another possible way to spell English, but some serious discussion of what a better spelling system should be like’ (p. 7).

Part 2 is his enumeration of the criteria we should employ for such a reform. As a model, Burling dreams of a ‘Korean solution’ to English spelling: ‘Devise a good spelling system, persuade people to use it for limited purposes, and then hope it will gradually spread to wider use’ (p. 81).

Rather cleverly, at this point, Burling sidesteps the notion of proposing a specific set of reforms. Instead, he uses Part 2, to establish the criteria upon which reforms might be taken. A critical step for sure, and one which he seems to believe was lacking in the many failed attempts of the past. His 15 criteria reflect a deep understanding of both linguistic rules and the need for clarity. Criterion number eight, for example, ‘syllabic consonants’ (p. 93). points out that words such as kitten and button have no discernible vowel sound in their second syllable. Phonetically, these might best be represented as kitn and butn, especially considering that our existing alphabet has no vowel which would accurately represent this shortened vowel sound. Only the schwa (ə) used phonetically in dictionaries might rise – or shrink – to such a task.

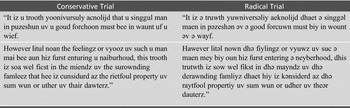

As Part 2 delves deeply into rhotic and non-rhotic vowels, intervocalic consonants, variable mergers, reduced schwas, free variation, and invariant schwas, Burling will probably lose the casual reader. But time spent working through these linguistic dissections is rewarded. Take for example his rendering of the first page of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice (Reference Austen1813). Here, Burling presents two amusing ‘trials’ in order to provide a glimpse of what spelling reform might eventually look like. These hypothetical experiments re-assert the key assumptions of his argument, mainly, that after a reform of spelling, ‘with time and practice, reading would gradually speed up again,’ and that after a substantial reform ‘sentences would be understood as quickly and easily as [they are] now’ (p. 142).

The first trial, which Burling calls ‘conservative,’ presents the kind of reforms a group of educated non-linguists might propose: simplifications of spelling, the use of orthographic representations currently in place – no new letters, just an elimination of redundancies. The second, ‘radical’ trial demonstrates the changes a highly-trained linguist might present, in order to represent every nuance possible in the pronunciation of each word.

Table 1: Burling's re-imagining of Chapter One of Pride and Prejudice (1813) after hypothetical spelling reforms

Through all of his arguments, examples, and anecdotes, Burling underscores the need to make practical reforms in the interest of literacy. Each chapter and section concludes with a plea to put the literacy of future generations to the fore, and set aside concerns about tradition and the specific challenges of reformation.

Spellbound: Untangling English Spelling is a small book – a manifesto of sorts – which refuses to shy away from the enormity of the task at hand: the reformation of English orthography. While stopping short of providing a debatable proposition for such a reformation, Burling persuasively argues for its necessity, and the far-reaching ramifications of status quo.

ADAM DEDMON, [MATESOL., M. Ed. Leadership] is the English Department Chair at Douglas High School, in Minden, Nevada. He has taught all grade levels from sixth grade to graduate courses. He studied at the University of Nevada, Reno, (where he also taught in the MATESOL program,) and at the Université de Pau, in France. He has also taught IB English in Istanbul, Turkey at the Koç High School. Email: [email protected]

ADAM DEDMON, [MATESOL., M. Ed. Leadership] is the English Department Chair at Douglas High School, in Minden, Nevada. He has taught all grade levels from sixth grade to graduate courses. He studied at the University of Nevada, Reno, (where he also taught in the MATESOL program,) and at the Université de Pau, in France. He has also taught IB English in Istanbul, Turkey at the Koç High School. Email: [email protected]