Introduction

The taxonomy and geographical distribution of the parasitic nematode fauna of aquatic organisms is poorly known in the Neotropics (e.g. Moravec, Reference Moravec1998; Salgado-Maldonado et al., Reference Salgado-Maldonado, García-Aldrete and Vidal-Martinez2000; Caspeta-Mandujano, Reference Caspeta-Mandujano2005). The life cycles of these nematodes are even less well known, with only 13 papers on the subject published for the Neotropics, compared to the 61 life cycles described for the Palearctic realm (supplementary table S1). Knowledge of the life cycles of parasitic nematodes of Neotropical aquatic organisms in most cases is restricted to Anisakidae and Camallanidae families (supplementary table S1).

With respect to dracunculid nematodes parasitizing fish, there exist 192 species belonging to eight families (Anguillicolidae, Daniconematidae, Guyanemidae, Lucionematidae, Micropleuridae, Philometridae, Skrjabillanidae and Tetanonematidae) (Moravec, Reference Moravec2004; Moravec and de Buron, Reference Moravec and de Buron2013). Of eight families belonging to the superfamily Dracunculoidea, only 29 nematode life cycles have been described, 15% of which are members of the families Philometridae, Angullicolidae, Skrjabillanidae and Daniconematidae (Moravec, Reference Moravec2004). The life cycles of dracunculid nematodes parasitizing fish in temperate latitudes have been reported by Moravec (Reference Moravec2004) (supplementary table S1); however, there is a lack of information on the life cycle of dracunculid nematodes parasitizing fish in the tropical zone.

One of the few partial nematode life cycles described in Mexico is that of the dracunculid Mexiconema cichlasomae Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992), for which the larval stage has been reported in the parasitic branchiurid Argulus yucatanus (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo1999), and the adult stages in the Mayan cichlid Cichlasoma urophthalmus (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992), both from the Celestun coastal lagoon, Yucatan, Mexico (May-Tec et al., Reference May-Tec2013). However, the lack of distinguishing characteristics in the larval stages described by Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo1999) casts doubt about whether they truly belong to M. cichlasomae. Furthermore, despite the careful description of the adult stages of M. cichlasomae in its definitive host C. urophthalmus, the larval stages present in this host have not been properly described up to now. An alternative to overcome the problem of linking the larval stages of nematode parasites is the use of molecular markers, which have been used on parasites related to human and animal health (Klimpel and Palm, Reference Klimpel, Palm and Mehlhorn2011; Borges et al., Reference Borges2012; Liu et al., Reference Liu2015). However, molecular marker studies linking larval stages and adult nematodes of wildlife organisms are scarce (Loung and Hudson, Reference Loung and Hudson2012; Blasco-Costa and Poulin, Reference Blasco-Costa and Poulin2017). In addition, molecular studies using the small subunit (SSU) ribosomal marker in wildlife nematodes to explore phylogenetic relationships have been particularly useful for establishing the phylogenetic position among nematode families of the superfamily Dracunculoidea, such as Daniconematidae, Philometridae and Skrjabillanidae (Blaxter et al., Reference Blaxter1998; Holterman et al., Reference Holterman2006; Nadler et al., Reference Nadler2007; Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011; Choudhury and Nadler, Reference Choudhury and Nadler2016; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Pereira and Luque2017). In this context, it is plausible to use this marker to link larval and adult nematodes to find species boundaries and to determine whether there are biological reasons to support their phylogenetic relationships. Furthermore, based on molecular phylogenetic analyses, several members of the paraphyletic families Daniconematidae, Skrjabillanidae and Philometridae form a monophyletic group infecting the serosa of freshwater, brackish and marine fishes, and develop in blood-sucking branchiurids, e.g. genera Mexiconema (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992), Molnaria (Moravec, Reference Moravec1968), Skrjabillanus (Shigin and Shigina, Reference Shigin, Shigina and Skryabina1958), Esocinema (Moravec, Reference Moravec1977) and Philonema (Kuitunen-Ekbaum, Reference Kuitunen-Ekbaum1933) (Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011). However, M. cichlasomae was not included in these analyses, and therefore its phylogenetic identity was not tested as a member of the Daniconematidae family associated with branchiurid intermediate hosts (Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011; Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo, Reference Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo2011).

Therefore, our aims were threefold: (1) test the possible life-cycle links of M. cichlasomae between larval stages in A. yucatanus and adults in C. urophthalmus using the SSU marker; (2) describe morphologically the larval stages of M. cichlasomae in both its intermediate and definitive hosts; and (3) re-evaluate the molecular phylogenetic position of M. cichlasomae into the Daniconematidae family.

Materials and methods

Collection of hosts, ectoparasite branchiurids and endoparasite nematodes

As part of our study on the life cycle of M. cichlasomae, from January to July 2016 a total of 105 C. urophthalmus (15 fish examined each month) were caught by hook and line from the middle zone of the Celestun tropical lagoon, Yucatan Peninsula (20°52′46.68″N, 90°21′15.4″W) (fig. 1). We collected A. yucatanus branchiurids from the body of each C. urophthalmus caught, and examined them for nematode larvae (May-Tec et al., Reference May-Tec2013; Sosa-Medina et al., Reference Sosa-Medina, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo2015). During the study period we collected 473 A. yucatanus and 29 M. cichlasomae larvae (supplementary table S2). For molecular studies, from 45 C. urophthalmus collected during January–March 2016, we collected a total of 124 A. yucatanus parasitized with nine M. cichlasomae larvae. The live fish captured were transported to the laboratory in a tank of 200 l of lagoon water and oxygen. Once there, the body surface of each fish was examined under a stereomicroscope, looking for A. yucatanus, and each A. yucatanus was examined for M. cichlasomae larvae. The parasitic specimens for morphological studies were collected and fixed in 96% ethanol, and for molecular analysis with 100% ethanol. Mexican authorities, in this case the National Committee of Fisheries and Aquaculture (PPF/DGOPA-070/16) issued the collecting permits.

Fig. 1. Map of the study area, the middle zone of the Celestun coastal lagoon, Yucatan, Mexico.

Morphological data and morphometric analyses

The protocols for the morphological study of M. cichlasomae larvae were based on the taxonomic description of nematode larvae of Skrajabillanidae family, given their taxonomical and biological similarities such as the measurements of the larval stages, the use of branchiurid ectoparasites Argulus sp. as an intermediate host and the absence of free-living stages (Tikhomirova, Reference Tikhomirova1970, Reference Tikhomirova and Kalinin1975, Reference Tikhomirova1980; Molnár and Székely, Reference Molnár and Székely1998; Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011). The morphological terminology for each stage of maturity followed that of Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992, Reference Moravec1994), Hugot and Quentin (Reference Hugot and Quentin2000) and Caspeta-Mandujano and Mejía-Mojica (Reference Caspeta-Mandujano and Mejía-Mojica2004). The morphological examination of the nematodes was performed using an optical microscope (Olympus BX 50) equipped with a digital camera (Evolution MP). The measurements were in micrometers (μm), presented here as the ranges followed by the mean and standard deviation in parentheses, and were obtained using the Image J 1.50e software (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012). Statistica v. 8.0 software (www.statsoft.com) was used for statistical analysis of the morphometric data. Lastly, several of our morphological measurements for the larval stages of M. cichlasomae were compared with those of other members of families Philometridae and Skrjabillanidae (supplementary table S3) to determine their phylogenetic affinity.

Eggs (ɷ), embryos (E) and first larval stage (L1) were obtained from gravid M. cichlasomae females removed from mesenteries and body cavities of C. urophthalmus. The second (L2) and third larval stages (L3) of M. cichlasomae were collected from A. yucatanus; the juvenile stage (L4) was found in the mesenteries of C. urophthalmus. Eggs, embryos and larvae were cleared in glycerin (1 : 2) and then mounted on glass slides with glycerine jelly. Measurements were based on at least 10 specimens of each developmental stage, slightly flattened under cover-glass pressure. The morphological measurements of M. cichlasomae embryos and larvae (L1, L2, L3 and L4) were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine differences in size of these larval stages (Sokal and Rohlf, Reference Sokal and Rohlf2009). The significance of all statistical analyses was established at α < 0.05.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

To obtain a small fraction of the genetic variability of M. cichlasomae we used samples of worms of different host individuals from the same locality (avoiding sequencing all the individuals from the same host). Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from one individual adult male nematode and one individual adult female nematode from C. urophthalmus. We also extracted DNA of four larvae obtained from A. yucatanus. DNA extraction was performed using the DNA easy blood and tissue extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The SSU rDNA gene fragment was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Saiki et al., Reference Saiki1988), using D–1F forward (5′–GCC TAT AAT GGT GAA ACC GCG AAC–3′) and D–1R reverse (5′–CCG GTT CAA GCC ACT GCG ATT A–3′) (Wijová et al., Reference Wijová2005). The reactions were prepared using the Green GoTaq Master Mix (Promega). This procedure was carried out using an Axygen MaxyGene thermocycler. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturing step of 5 minutes at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 92°C for 30 s, 54°C for 45 s, 72°C for 90 s, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. The PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel using TAE 1X buffer and observed under UV light using the QIAxcel®Advanced System. PCR products were purified and sequencing carried out in a specialized laboratory, Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ, USA (https://www.genewiz.com/).

Molecular data and phylogenetic reconstruction

Sequences of M. cichlasomae obtained in this study were edited using the platform Geneious Pro v.5.1.7 (Drummond et al., Reference Drummond2012). All sequences, together with published representative outgroup (OG) sequences of Daniconematidae, Skrjabillanidae, Philometridae and Camallanidae (supplementary table S4), used previously by Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo (Reference Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo2011) and Černotíková et al. (Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011), were aligned using an interface available with MAFFT v.7.263 (Katoh and Standley, Reference Katoh and Standley2016), an “auto” strategy and a gap-opening penalty of 1.53 within Geneious Pro, and a final edition by eye in the same platform. The best substitution model for the DNA dataset was chosen under the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz1978) using the “greedy” search strategy in Partition Finder v.1.1.1 (Lanfear et al., Reference Lanfear2012, Reference Lanfear2014). The nucleotide substitution model that best fit was K80 + I (Kimura, Reference Kimura1980). The Gblocks website (Castresana, Reference Castresana2000; Talavera and Castresana, Reference Talavera and Castresana2007) was used to detect ambiguously aligned hypervariable regions in the SSU dataset, according to a secondary structure model; these were excluded from the analyses. Additionally, the proportion (p) of absolute nucleotide sites (p-distance) (Nei and Kumar, Reference Nei and Kumar2000) was obtained to compare the genetic distance between species of Dracunculoidea nematodes (without outgroups, i.e. Camallanus oxycephalus, Camallanus hypophthalmichthys and Procamallanus pintoi). The P-value matrix was obtained using MEGA v.7.0 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016), with variance estimation with the bootstrap method (1000 replicates) and with a nucleotide substitution (transition + transversions) uniform rate.

Phylogenetic reconstruction was carried out using Bayesian Inference (BI) through MrBayes v.3.2.3 (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist2012). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using two parallel analyses of Metropolis-Coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for 20 × 106 generations each, to estimate the posterior probability (PP) distribution. Topologies were sampled every 1000 generations and the average standard deviation of split frequencies was observed to be less than 0.01, as suggested by Ronquist et al. (Reference Ronquist2012). The robustness of the clades was assessed using Bayesian Posterior Probability (PP), where PP > 0.95 was considered to be strongly supported. A majority consensus tree with branch lengths was reconstructed for the two runs after discarding the first 5000 sampled trees. The Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction was run through the CIPRES Science Gateway v.3.3 (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010).

Results

Morphological characteristics of eggs, embryos and larvae (L1) in Mexiconema cichlasomae gravid female

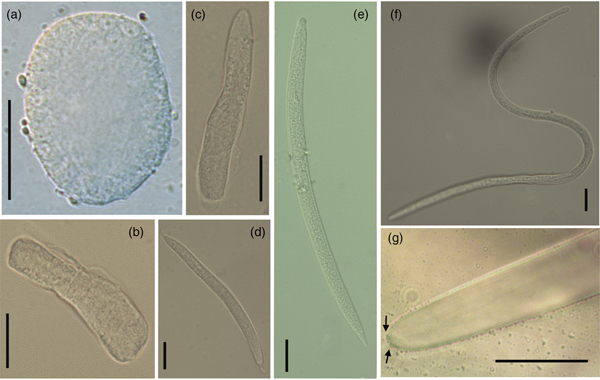

The uterus of an M. cichlasomae gravid female is prodelphic, and L1 larvae were found from the posterior to the anterior ends of the uterus. The mature eggs (n = 10) were almost spherical, thin-walled, and in a cell division process; 21.96–36.02 (26.27 ± 4.68) long, 10.38–22.18 (16.40 ± 4.14) wide (fig. 2a). Developed embryos (n = 10) were localized in the middle of the uterus, longer than eggs (57.95–78.25 (70.79 ± 11.63) long, 11.27–16.68 (13.80 ± 1.54) wide), but without evidence of organ development (fig. 2b, c). In the anterior third of gravid females, close to the vulva, we found M. cichlasomae L1 (n = 10) presenting a slender, translucent body, with rounded head, sharply pointed tail and measuring 122.23–173.21 (134.00 ± 11.63) long and 6.08–11.12 (8.49 ± 1.33) wide (fig. 2d). The gravid females (n = 10) had, on average, 189–468 (339.71 ± 107.82) L1 larvae.

Fig. 2. Morphology of Mexiconema cichlasomae larval stages present in uterus of gravid females in Cichlasoma urophthalmus and its intermediate host Argulus yucatanus. (a) Egg (150×), (b, c) embryos (40×) and (d) first larval stage (L1) in gravid females of M. cichlasomae (40×); (e, f) second and third larval stages (L2–L3) of M. cichlasomae in A. yucatanus (40×); (g) tail of M. cichlasomae (L3) with two button-like processes (indicated by black arrows) at the tip (100×). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Mexiconema cichlasomae larvae (L2–L3) in Argulus yucatanus

The M. cichlasomae L2 larvae (fig. 2e) were found in the haemocoel and natatory appendages of A. yucatanus. Their measurements were 153.00–227.68 (188.27 ± 24.35) long, 5.96–9.59 (7.20 ± 1.33) wide (n = 10). This larval stage presented a smooth cuticle, rounded anterior end and conical tail (fig. 2e). The body of the L3 was 324.02–347.93 (331.93 ± 11.51) long, 7.00–7.6 (7.26 ± 0.30) wide (n = 6) (fig. 2f), with an oesophagus not clearly divided into muscular and glandular parts (48.40–52.85 (50.41 ± 2.25) long, 3.6–4.49 (4.03 ± 0.44) wide) and a tail with two button-like processes (fig. 2g). In the mesenteries of C. urophthalmus, we found L4 stage larvae (2060.00–2490.00 (2292.00 ± 210.16) long, 35.00–42.00 (39.20 ± 2.77) wide; n = 5). There were significant differences in the total length of L1 found in gravid females and L3 in A. yucatanus (one-way ANOVA F2, 27 = 32.46, P < 0.05) (supplementary fig. S1). We observed that only female A. yucatanus (18 of 231 females examined) with M. cichlasomae larvae (n = 29), and not males, were parasitized (242 males examined). The size of A. yucatanus did not present a statistically significant association with the number of M. cichlasomae larvae (R2 = 0.04, P > 0.05).

DNA sequences and phylogenetic tree

A total of six SSU assembly sequences (forward and reverse) were obtained from two adult M. cichlasomae specimens (male and female) and four M. cichlasomae larval specimens from C. urophthalmus and A. yucatanus, respectively (supplementary table S4). Sequences of SSU gene fragments were obtained with a range of 1668–1702 base-pairs (bp). The SSU sequences of adult nematodes from C. urophthalmus were identical to those of larval nematodes from A. yucatanus. Therefore, both nematode stages correspond to M. cichlasomae. Nucleotide sequence variation in the SSU alignment from dracunculids to the phylogenetic reconstruction had 1214 conserved sites, 347 variables sites, 278 parsimony-informative sites and 69 singleton sites.

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was undertaken for seven M. cichlasomae individuals and one of M. africanum, three skrjabillanid species, two philometrid species plus three camallanid species, to test life-cycle links between the larval stages and adult nematodes with molecular data, and re-evaluate the phylogenetic position of M. cichlasomae. The SSU tree clearly shows that all samples of M. cichlasomae from C. urophthalmus and A. yucatanus were nested together (monophyletic group with PP ≥ 0.95). The phylogenetic analysis recovered a monophyletic group comprising three polyphyletic taxa each, i.e. Daniconematidae (M. cichlasomae and M. africanum; Mexiconema genus is not a monophyletic group), Skrjabillanidae (Esocinema bohemicum, Molnaria intestinalis and Skrjabillanus scardinii) and Philometridae (Philonema oncorhynchi and Philonema sp.) (fig. 3). The genetic distance values of M. cichlasomae relative to other dracunculids was 3.93% with M. intestinalis, 4.02% with S. scardinii, 4.45% with M. africanum, 6.46% with E. bohemicum, 5.94% with P. oncorhynchi and 5.76% with Philonema sp. (table 1).

Fig. 3. Bayesian tree inferred from the small subunit (SSU) ribosomal DNA of Mexiconema cichlasomae adults and larvae. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Filled black circles above/below branches represent Bayesian posterior probability ≥ 0.95. Bold font indicates new sequences generated in the present study; their GenBank accession numbers are provided in supplementary table S4.

Table 1. Distance matrix of uncorrected p-distances within skrjabillanid nematode species, derived from SSU by Bayesian phylogenetic analyses (percentage values).

Discussion

Our molecular and phylogenetic results strongly suggest that the nematode larvae parasitizing A. yucatanus are conspecific to those infecting the cichlid fish C. urophthalmus as adults, and that both belong to Mexiconema cichlasomae. This is relevant because this is the first complete life cycle of a dracunculid nematode parasite of fishes described for the Neotropics. Below, we stress several relevant biological aspects of the larval stages in both A. yucatanus and C. urophthalmus, compare the life cycle of M. cichlasomae to that of other dracunculid nematodes and discuss the systematic classification of M. cichlasomae as molecular phylogenetic reconstruction allows.

Description of larval stages of Mexiconema cichlasomae

There is intraspecific variation in the morphological measurements of L1 of M. cichlasomae in different species of definitive hosts. The mean length of L1 larvae (134.00 ± 11.63) from M. cichlasomae females from C. urophthalmus in the present study was longer than that of M. cichlasomae L1 from Xiphophorus helleri Heckel, 1848 (Cyprinodontiformes: Poecilidae) (100 μm long) (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Jiménez-García and Salgado-Maldonado1998). This difference in total length can be associated with intraspecific variability given the different species of definitive hosts. However, we suggest the need to undertake molecular examination of M. cichlasomae from X. helleri for comparison with M. cichlasomae from C. urophthalmus to rule out possible misidentifications.

With respect to the L2 and L3 found in A. yucatanus, we found evidence of increased development, as larvae in the crustacean were twice the size compared to L1 in M. cichlasomae gravid females in C. urophthalmus. This means that A. yucatanus probably acts as an intermediate host, in which L3 develop to be able to infect the definitive host (C. urophthalmus in this case). This result concurs with Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo1999), who suggested that A. yucatanus acts as intermediate host of M. cichlasomae in Yucatan, Mexico.

In addition to the difference in size, the main difference observed between L1 larvae retrieved from uterus and L2 from A. yucatanus was that the tapered tail of these larval stages became a rounded tail of L3 larvae, with two small cuticular processes in the tip, which probably become the digital process typical of adult M. cichlasomae (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992). Finally, we observed the presence of very small larvae of M. cichlasomae in A. yucatanus, presumably L1, of < 100 μm. This is not surprising, as infection of L1 of M. cichlasomae in A. yucatanus has also been reported by Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo1999).

The life cycle of Mexiconema cichlasomae

Based on morphological and molecular links identified in the present study, we suggest that M. cichlasomae larvae are ingested by two, probably complementary, processes. During the first process the branchiurid is infested by ingesting L1 while sucking blood from C. urophthalmus. The L1 then develops into L3 and is transmitted again during the blood-sucking process. During the second process, the fish host becomes infected by ingesting infected branchiurids with L3, e.g. cleaning symbiosis (fig. 4). This process of active removal of ectoparasites from the body surface has been observed in various fish species (Poulin and Grutter, Reference Poulin and Grutter1996; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson2010; Quimbayo et al., Reference Quimbayo2017). In C. urophthalmus, once in the gut L3 larvae probably migrate through the pneumatic duct connecting the oesophagus with the swim bladder. However, this ontogenetic migration process needs confirmation through histology. In fact, the presence of a pneumatic conduct in C. urophthalmus has been corroborated by Cuenca-Soria et al. (Reference Cuenca-Soria2013).

Fig. 4. Life cycle of Mexiconema cichlasomae in Cichlasoma urophthalmus (definitive host) and Argulus yucatanus (intermediate host). Ar, Artery; C, Capillaries; Sb, Swim bladder; L1, First larval stage; L2, Second larval stage; L3, Third larval stage (infective stage); L4, Juvenile stage.

The development of M. cichlasomae in the definitive host should be as follows. Once in the fish, the L3 should migrate from the peripheral blood into the abdominal cavity, mesenteries, swim bladder and serous membrane covering the intestine (Vidal-Martínez et al., Reference Vidal-Martínez2001). An alternative way for larval migration from A. yucatanus ingested by cleaning symbiosis is through the pneumatic conduct directly into the swim bladder. Once in these microhabitats, the nematode larvae moult into L4, develop secondary sexual characteristics typical of adults, and mate. In the case of gravid females, they burst, releasing approximately 340 ± 108 L1 larvae per individual (authors, pers. obs.), which eventually migrate to the fish blood vessels, circulating until another A. yucatanus feeds on this infected fish, acquiring L1 larvae again (fig. 4).

The life cycle of M. cichlasomae is similar to that of the daniconematid nematode S. scardinii, as females of both species release their first larval stage into the surrounding tissues of fish. These larvae become available in the fish bloodstream to blood-sucking fish lice Argulus spp. (Moravec, Reference Moravec2004; Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011). The host specificity of A. yucatanus, and that of M. cichlasomae, is apparently rather low. Argulus yucatanus parasitizes several other fish species, such as Floridichthys carpio (Günter, 1866) (Cyprinodontiformes: Cyprinodontidae), Archosargus rhomboidales (Linnaeus, 1758) (Perciformes: Sparidae) (Sosa-Medina et al., Reference Sosa-Medina, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo2015) and Sphoeroides testudineus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Tetraodontiformes: Tetraodontidae) (Aguirre-Macedo and Vidal-Martínez, unpublished data at the Laboratory of Aquatic Pathology Cinvestav-Mérida), all of which are marine or brackish-water fishes from Mexican coastal lagoons of the Gulf of Mexico (May-Tec et al., Reference May-Tec2013; Sosa-Medina et al., Reference Sosa-Medina, Vidal-Martínez and Aguirre-Macedo2015). The adult forms of M. cichlasomae have been reported from freshwater and euryhaline fish species of the families Cichlidae, Bagridae (ex Ariidae) (Siluriformes) and Poecillidae from freshwater and coastal lagoons of the Gulf of Mexico (Aguilar-Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar-Aguilar, Llorente-Bousquets and Morrone2005; Salgado-Maldonado, Reference Salgado-Maldonado2006; Salgado-Maldonado et al., Reference Salgado-Maldonado2011; Salgado-Maldonado and Quiroz-Martínez, Reference Salgado-Maldonado and Quiroz-Martínez2013). In fact, adult M. cichlasomae have even been reported in a nurse shark Ginglymostoma cirratum (Bonnaterre, 1788) (Orectolobiformes: Ginglymostomatidae) (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Jiménez-García and Salgado-Maldonado1998; Merlo-Serna and García-Prieto, Reference Merlo-Serna and García-Prieto2016). In this context, it would not be surprising if M. cichlasome were found in other fish species occurring in freshwater, brackish water or even marine waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Phylogenetic context of Mexiconema cichlasomae

The molecular phylogenetic reconstructions showed that M. cichlasomae is related to the skrjabillanids M. intestinalis and S. scardinii, as previously revealed by Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo (Reference Mejía-Madrid and Aguirre-Macedo2011). However, we detected that the genus Mexiconema has at least two independent origins, i.e. it is a paraphyletic group (fig. 3). At the moment, the taxonomic categories of the Mexiconema genus are variable. For example, based on molecular phylogenetic analysis, Černotíková et al. (Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011) suggested the transfer of Mexiconema from Daniconematidae to Skrjabillanidae. On the other hand, when Černotíková et al. (Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011) found the family Daniconematidae to be non-monophyletic (that included Mexiconema genus), they suggested the family Daniconematidae should be lowered to subfamily level (Daniconematinae) and transferred to the family Skrjabillanidae. In this study, we support the transfer of M. cichlasomae and M. africanum to the family Skrjabillanidae, based on the values of genetic divergence (3.93–6.46%) between taxa that represent the daniconematids (i.e. Mexiconema spp.) and skrjabillanids (table 1). However, we do not support the proposal to lower the family Daniconematidae to Daniconematinae; for such a move, it would be necessary to test the phylogenetic position of two additional monotypic daniconematid genera: Daniconema Moravec & Køie, 1987 and Syngnathinema Moravec et al., 2001 (Moravec, Reference Moravec2006; Moravec et al., Reference Moravec2009). Additionally, Mexiconema as a genus currently includes three species: M. cichlasomae, M. africanum and M. liobagri (Moravec et al., Reference Moravec, Vidal-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado1992; Moravec and Nagasawa, Reference Moravec and Nagasawa1998; Moravec and Shimazu, Reference Moravec and Shimazu2008; Moravec et al., Reference Moravec2009); therefore, it is necessary to include molecular sequences of M. liobagri to support or contrast with the paraphyletic pattern detected for the genus Mexiconema.

In this study, M. cichlasomae is included in a clade (monophyletic group) with representatives from two paraphyletic families (Skrjabillanidae and Daniconematidae), which include parasites of fishes without free-living stages and using branchiurid ectoparasites, such as Argulus sp., as intermediate hosts (Tikhomirova, Reference Tikhomirova1970, Reference Tikhomirova and Kalinin1975, Reference Tikhomirova1980; Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011). In this context, this clade with the putative name “Skrjabillanidae” (sensu laxo Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011) represents a natural group with diversification patterns, particularly regulated at the level of intermediate host (i.e. branchiurids), and host-switching events at the level of the definitive hosts. A future study involving cophylogenetic analyses may shed light on these evolutionary processes (e.g. Martínez-Aquino, Reference Martínez-Aquino2016; Vanhove et al., Reference Vanhove2016).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X18000524

Acknowledgements

We thank staff of the laboratory of Patología Acuática: Clara Vivas-Rodríguez, Gregory Arjona-Torres, Arturo Centeno-Chalé, Francisco Puc-Itzá, Jhonny G. García-Tec, Ylce Y. Ucan Maas and Nadia Herrera Castillo, CINVESTAV-IPN, Unidad Mérida, México. Germán López-Guerra helped to collect nematodes. We are grateful to Abril Gamboa-Muñoz and Dr José Q. García-Maldonado for their technical assistance in the molecular laboratory. We thank Dr Fadia Sara Ceccarelli, who reviewed the first draft of this manuscript and made very useful suggestions regarding the phylogenetic analyses, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticisms.

Financial support

ALM-T and AM-A at the laboratory of Aquatic Pathology at CINVESTAV-IPN were supported by the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico - Mexican Ministry of Energy - Hydrocarbon Trust, project (201441). This is a contribution of the Gulf of Mexico Research Consortium (CIGoM).

Conflict of interest

None.