In the April 2010 issue of PS: Political Science and Politics, Christopher Soper discussed his use of music in a large introductory American politics course. At the beginning of most classes, and in the middle of others, he plays songs while projecting the lyrics on PowerPoint slides. He then engages his students in a discussion about how the lyrics relate to topics in American politics. Soper found that playing songs improved his ability to communicate with students because it linked learning with their favorite expressive medium. He was particularly impressed by their ability to offer sophisticated interpretations of the lyrics and analogies to political issues: “This has perhaps been the most important benefit of the assignment: taking the passion and information that students have about music and getting them to think about the same topics as they relate to politics” (Soper Reference Walczak and Reuter2010, 367). He suggested that music could be used to teach “introductory classes in comparative politics, international relations, or even political theory” (Soper Reference Walczak and Reuter2010, 367).

Since the fall semester of 2008, I have used music and lyrics in my introductory political-theory courses at Touro College. During the semester, I play approximately 20 songs that raise issues discussed by political theorists from Plato to Marx. The songs are drawn from a variety of genres; most are Broadway show tunes and rock music from the 1970s and 1980s. Like Soper, I use class discussion about the lyrics to further students’ understanding of specific issues. Unlike Soper, I link the songs to specific theorists rather than topics. I find that students not only relish the musical interlude but they also enjoy comparing the ideas in the lyrics with the readings. I find that using songs improves their understanding of political theory, and I recently added songs to my advanced course on contemporary political theory.

This article outlines a pedagogical method for political theory that has not been discussed previously in academic literature. The first section of the article explains how music and song lyrics contribute separately to students’ understanding of political theory. The second section reviews the use of music and lyrics in teaching other social sciences and explains how my proposal differs from previous applications. The third section explains in detail several ways that songs help me to teach political theory as well as how some of my students responded to my pedagogy. The fourth section presents recommendations for other teachers who are interested in using music to introduce their students to political theory.

WHY STUDYING BOTH MUSIC AND LYRICS HELPS STUDENTS LEARN POLITICAL THEORY

Lyrics and music make very different contributions to my political-theory classes. Lyrics are useful primarily because they expand opportunities for students to engage in critical thinking about political theory. After they hear a song, I ask them to explain the meaning of the lyrics without reference to the reading. Once they have interpreted the lyrics, I ask how their interpretations relate to the readings for class. This provides the opportunity to find analogies to theoretical ideas and make comparisons with ideas in the songs. As the students articulate similarities and differences, they engage in analytical reasoning that helps them to better understand and evaluate the concepts presented in the readings. Class discussion of lyrics transforms the students from passive readers and listeners into critical thinkers about political theory.

Students value the exploration of the meaning of song lyrics because music occupies an important place in their lives. (Lenning Reference Lenning2012; Levy and Byrd Reference Levy and Byrd2011). Furthermore, they often draw insight and inspiration from songs that they hear; therefore, discussing lyrics brings to the classroom an activity to which they closely relate. In Book II of Plato’s Republic, students read about a magic ring that makes its wearer invisible when it is turned inward. Glaucon states that possessing this ring would not affect the behavior of a just man, but an unjust man would use the power of invisibility to break laws with impunity. I use the Magnetic Fields song “My Evil Twin” to introduce the discussion of the “Ring of Gyges.” One student wrote, “I love this song; I posted the lyrics on Facebook the day that you played it in class. I am not sure if I wish I had an evil twin, or if I would like to be the evil twin, but it really resonates for me.” I also encourage my students to seek out other songs that provide useful analogies to political theory. Every semester, they have the option of writing a paper that compares the lyrics of a song to the ideas of one theorist that we read. If their song meets my standards, I add it to the playlist for the course. “My Evil Twin” is one such song.

Listening to the music that accompanies the lyrics achieves a different objective: improving students’ memory. When a person hears a song for the first time, the mind establishes a link between the song and what the person is doing at the time. As Levitin explains in This Is Your Brain on Music (2006, 162): “A song playing comprises a very specific and vivid set of memory cues. . . . [T]he music that you have listened to at various times in your life is cross-coded with the events of those times. That is, the music is linked to events of the time, and those events are linked to the music.” When listeners hear the song again, memories associated with their first encounter reappear. These might be a memory of a place where the song was heard, a person that the listener was with at the time, or the discussion that was connected to the song. According to Levitin (Reference Levitin2006, 162): “[A]s soon as we hear a song that we haven’t heard since a particular time in our lives, the floodgates of memory open and we’re immersed in memories. The song has acted as a unique cue. . . .”

When listeners hear the song again, memories associated with their first encounter reappear. These might be a memory of a place where the song was heard, a person that the listener was with at the time, or the discussion that was connected to the song.

I was unaware of how long lasting these cues can be until I encountered a student from my 2008 theory class at a political science dinner five years later. When she took my course, she heard the Ace of Base song, “The Sign,” which contains numerous allusions to Plato’s allegory of the cave. She told me that when she heard the song five years later, she remembered many of the specific analogies that were discussed in class. A more recent student supported her observation: “The music definitely made the course more enjoyable and understandable as well as memorable. I may not remember exactly what each theorist said, but I will remember which song relates to him and therefore the ideas he stands for.”

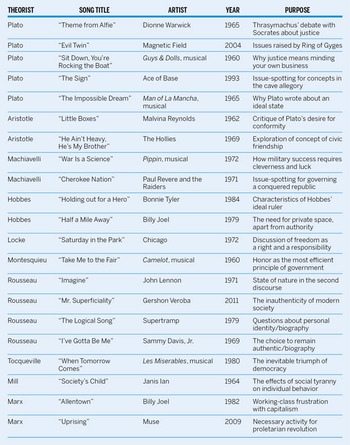

Most of the songs I use—which are listed in table 1—are more than 25 years old, which means that they often are unfamiliar to my students. This is fortuitous because when listeners hear a familiar song, it is likely that they have already formed a mental association with it. Levitin (Reference Levitin2006, 162) noted that familiar songs “are not very effective cues for retrieving memories if those songs have continued to play all along and you’re accustomed to hearing them….” This is a good reason to avoid using contemporary hit songs—unless there is no better song that presents the desired analogies. Because repeat listening reinforces students’ memories, I encourage them to listen to the songs again, especially when they study for exams. One student even changed her ringtone to a song that we listened to in class.

Table 1 Songs Used in Introduction to Political Theory, Fall Semester 2014

OTHER INSTRUCTORS HAVE USED MUSIC AND LYRICS DIFFERENTLY

As Soper (Reference Walczak and Reuter2010) noted, there are relatively few publications that address the pedagogical benefits of playing songs in political science classes. I have not found any that discuss analogizing songs to specific political theorists. Footnote 1 The impetus for my use of songs was The Beatles and Philosophy, a 2006 collection of essays edited by Michael Baur and Steven Baur that related philosophical ideas to lines in Beatles songs. Although the concept was interesting, many of the essayists’ analogies seemed strained. Furthermore, even the editors had difficulty finding a purpose in linking philosophy to isolated Beatles lyrics; they concluded only that the essays “induced us to start thinking philosophically” (Baur and Baur Reference Baur and Baur2006, x). The Baurs’ book triggered my personal memories of songs that I associated with particular political theorists, which led me to begin using songs in my introductory theory class.

When choosing songs to help students understand political-theory texts, I try to find songs that, when taken as a whole, reflect important ideas in the works we read. This allows students to make analogies to the message of the entire song as well as to specific lines. While it is relatively easy to analogize specific lyrics to theoretical ideas, it is far more difficult to find songs that, as a whole, reflect those ideas. One example of how my approach differs from The Beatles and Philosophy involves John Lennon’s song “Imagine.” Whereas Baur and Baur (2006, 103) include this song because of a line that reflects Karl Marx’s goal of abolishing private property, I use the entire song to represent Rousseau’s (Reference Schmitt1755) idealized state of nature in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men. Every song I choose has multiple references to a specific theorist’s ideas, as well as a theme that relates to one of that theorist’s principal ideas.

Other scholars who have written about using music in college-level, non-music courses have linked songs to general concepts but not to specific theorists. For example, Levy and Byrd (2011, 67) examined how playing songs can improve courses on social justice. They recognized that “song lyrics can provide text for analysis and discussion,” but they analogized the lyrics only to general ideas of justice. They also suggested informing students of the social and political context of a song’s release to promote discussion of the songwriter’s intent. My approach is ahistorical: students are asked to focus solely on the lyrics and not the songwriter’s intent. However, I fully concur with Levy and Byrd that using songs “stimulates critical thinking and reflection, generates thoughtful discussion, and leaves lasting impressions” (2011, 70).

Several sociologists also have successfully linked songs to general theories in their discipline. Lenning (Reference Lenning2012) found that the lyrics of Tupac Shakur helped her to teach students about theories of criminology. She asked students to link Shakur’s lyrics to assumptions about why individuals break the law and respond differently to punishment. Ahlkvist (Reference Ahlkvist1999) asked students to use sociological concepts to study heavy metal music, during which they successfully identified applications of sociological theory. Walczak and Reuter (Reference Walczak and Reuter1994) asked students to identify analogies to sociological concepts in song lyrics and concluded that this exercise improved their comprehension of them. Martinez (Reference Martinez1994) found that song lyrics were effective in challenging students’ assumptions about race, class, and gender in a sociology class of the same name. All of these applications linked specific lyrics to general sociological theories, rather than to the ideas of a specific theorist.

FOUR WAYS I USE MUSIC TO TEACH POLITICAL THEORY

The first way that I use songs is to introduce a concept that is important to the theorist that we are studying. For example, Thomas Hobbes posits in Leviathan that because no ruler can attain the power to control every aspect of his subjects’ lives, there will always be freedom even in the most authoritarian state (Hobbes Reference Hobbes1651). To begin our discussion of this idea, I play Billy Joel’s song “Half a Mile Away,” which illustrates how people find freedom in the interstices where authority figures cannot see them. College students are quite jealous of their privacy and recognize that having private space can be more valuable than having the right to participate in politics. Exploring the need for privacy in the pursuit of happiness helps them to understand the attraction of a political theory that values preservation of life above all else.

“Half a Mile Away” has become one of the two most popular songs in my repertoire. When I surveyed my students about this song in the 2012 fall semester, one student wrote, “This was my favorite song of the whole course! This song seamlessly depicted the Hobbesian idea that there is always an area of life that the dictator cannot control.” Another wrote, “It was a simple yet central concept to Hobbes and one that we kept referencing throughout the semester. It was much easier to remember ‘Half a Mile Away’ than ‘Hobbes gives the people freedom to do what they want if the ruler doesn’t regulate it.’” A third student wrote, “The fact that this ‘private’ life is only ‘half a mile away’ was an effective method of ‘measurement’ to show the division between the two: close but not close enough to see.”

In my contemporary theory course, I use a song to help students understand Carl Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political. Schmitt believed that “The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy” ([1927] 1976, 26). My students have difficulty understanding why this distinction creates the potential for great evil because they view the terms “friend” and “enemy” through the lens of partisan rivalry for public office. To help them see the implications of Schmitt’s theory, I play the “Jet Song” from the Leonard Bernstein musical West Side Story. The song portrays the opposition between two rival gangs that see one another as enemies rather than as legitimate competitors for power. I use the Jets’ statement, “ev’ry Puerto Rican’s a lousy chicken,” to initiate a discussion about how Schmitt encourages stereotyping group members—and how those stereotypes were used to justify the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. My students’ comments suggest that the song achieved its objectives. One wrote, “Schmitt is kind of complicated and really theoretical, so this definitely helped to simplify it and allowed me to understand it better.” Another commented, “I hadn’t quite grasped how stark Schmitt’s view was of friend/enemy, and explaining it via the song made me understand just how extreme he is.”

The second way I use songs is to demonstrate how a theorist’s concept applies to a concrete situation. Baron Montesquieu ([1721] Reference Montesquieu and Davidson1899, 100) is famous for his statement, “[T]he most perfect [form of government] is that which attains its object with the least friction, so that the government which leads men by following their propensities and inclinations is the most perfect.” In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu (Reference Rousseau1749) praised the British monarchy for using honor to induce service to the state. Granting honor in exchange for service often costs the ruler little and motivates citizens to undertake great risks in pursuit of honor. Students accustomed to seeing monarchy as quaint and/or tyrannical rarely are convinced of Montesquieu’s argument merely by reading his explanation of why honor is the most efficient foundation for government.

I use the Jets’ statement, “ev’ry Puerto Rican’s a lousy chicken,” to initiate a discussion about how Schmitt encourages stereotyping group members—and how those stereotypes were used to justify the genocidal policies of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

To illustrate why honor is so efficient, I introduce students to the musical Camelot and the character of King Arthur’s Queen Guinevere. Although Guinevere views the French knight Lancelot du Lac as a threat to her husband’s Round Table, she has no money or authority to motivate other knights to challenge du Lac’s rise in prominence. However, as queen, she has the power to offer the knights the honor that comes with being her escort to a royal event, as is demonstrated in the song “Take Me to the Fair.” In that song, Guinevere offers three different knights the honor of accompanying her in the future if they are able to kill du Lac in battle: “I do applaud your noble goals/Now let us see if you achieve them/And if you do, then you will/Be the three who go/To the ball, to the show/And take me to the fair.” In my 2012 fall semester student survey, one student wrote that her favorite song was “Take Me to the Fair”: “I thought that it was the best explanation of the idea of the theorist it was talking about. I think it was probably so successful at making the ideas clear because it ‘showed’ us the ideas ‘in action.’” A second student commented, “I profess to having been confused by reading his text, but once I heard the song it clarified things pretty quickly. I also loved the way she used such petty prizes to hook the knights—like government officials use petty prizes such as dinner invitations and titles today.”

Another example of making a theorist’s argument more concrete involves John Stuart Mill. In On Liberty, he wrote about the pernicious effects of social tyranny; however, because my students are unfamiliar with Victorian norms, they have difficulty relating to many of his examples (Mill Reference Mill1859). I use Janis Ian’s 1965 song “Society’s Child” to present these effects in a modern context. “Society’s Child” illustrates how society reacts negatively to a white teenaged girl who is seen with a black male friend. Her mother forbids her to see him, her friends ostracize her, and other classmates and teachers confront her with “smirking stares.” The first two verses conclude with authority figures telling the girl not to see him anymore. In the third verse, she recognizes that it is futile to fight the racism that permeates her world: “One of these days I’m gonna stop my listening. . .But that day will have to wait for a while/Baby, I’m only society’s child/When we’re older things may change/But for now this is the way they must remain.” The song concludes with the singer surrendering to the norms of her society, internalizing its values, and telling her friend, “I can’t see you anymore baby/…No, I don’t want to see you anymore.” Social pressure has triumphed over individual liberty and stifled social progress, as it did in Victorian England at the time that Mill wrote his book.

A third way I use songs is to reinforce the students’ understanding of a particular theorist. I do this by asking them to use their newly-acquired knowledge to spot analogies in a song to that theorist’s ideas. My favorite song for issue-spotting is “The Sign” by Ace of Base, which presents the story of a woman who has broken away from the spell of a former lover, reexamined her views about him, and concluded that he is not as perfect as she once believed. The “sign” represents Plato’s sun as the source of knowledge. The singer’s journey takes her through the escape from the cave of incorrect beliefs, the discomfort of emerging into the sunlight of truth, and the ultimate recognition that false beliefs have been exchanged for knowledge. The singer expresses thoughts that draw ready comparisons to Book VII of the Republic: “Life is demanding, without understanding/I saw the sign, and it opened up my eyes/…No one’s gonna drag you up/To get into the light, where you belong/But where do you belong?” As one student commented, “I enjoyed this song very much and I think this song was absolutely perfect line for line to reflect Plato’s ideas of people leaving the cave, and our discussion proved even further how well the song fit with the theorist. This song was so great in every aspect I can almost believe it was actually referring to Plato’s Republic!”

The fourth way I use songs is for biography, although I have used this method only for Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Supertramp’s “The Logical Song” presents numerous analogies to Rousseau’s early life and his search for a career, when he pursued work as a composer while writing his first essays on political theory. The lines “watch what you say or they’ll be calling you a radical, a liberal, fanatical, criminal/Won’t you sign up your name, we’d like to feel you’re acceptable, respectable, presentable, a vegetable” capture the criticism he received for his theoretical writings, as well as the temptation of King Louis XV’s offer of a lifetime pension, which would have required him to refrain from political writing (Damrosch Reference Damrosch2005, 225). The song’s refrain, “Please tell me who I am,” reflects Rousseau’s search for authenticity and demonstrates his lifelong struggle to be true to himself. Students responded favorably to “The Logical Song” because they liked the music and because they found it helpful in understanding Rousseau’s motivations.

SUGGESTIONS FOR OTHERS INTERESTED IN USING SONGS TO TEACH INTRODUCTORY POLITICAL THEORY

If readers are sufficiently intrigued to consider playing songs in their political-theory classes, I have four recommendations. First, begin slowly. The first time I used music in my political-theory classes, I did not mention my plans until it was time to play the first song. This prevented students from developing the expectation that listening to music was a regular part of the study of political theory. Michael Baur (Hollander Reference Hollander2013, A17) warned that although it is tempting to use music to “become popular and trendy and cool,” using too many songs might cause the medium to overwhelm the message. Soper (2010, 366) expressed a similar concern that the overuse of songs “runs the risk of reinforcing the idea that the point of education is not so much to enlighten our students as to amuse them.”

Second, I recommend embedding edited versions of songs in PowerPoint slides. When I first began playing songs, I did so directly from iTunes, which meant I had to closely monitor songs that I planned to end early when the lyrics became repetitive. Now I create an MP3 version of each song and embed it directly in a PowerPoint slide, which allows me to delete long instrumental introductions and to end the clip at the exact thousandth of a second that I want. This reduces the amount of in-class time spent listening to songs, which could cramp opportunities for discussion (Soper Reference Walczak and Reuter2010). This also allows students to listen to the songs on their own time after class and while they study for exams.

Third, be flexible about when to insert the song into the class. I find that songs work best in the middle of class, when students have already been thinking about political theory. Only occasionally do I use them at the beginning of a class. I also find that students sometimes initiate discussion of the concept that I intend to link to the song; rather than postpone this discussion, I advance to the relevant slide and segue to the song. Being flexible about when to introduce a song promotes better discussion and provides an opportunity to seamlessly weave music into the class.

Fourth, recognize that not every song you play will meet your expectations. This is the seventh year that I have used music to teach political theory, and some songs that I choose still fall flat. Like many innovative approaches to teaching, using music to teach political theory involves taking risks. However, a less-than-satisfying discussion about a song does not prevent students from later finding enlightenment through the same song. Their appreciation of the song may develop later, and the inspiration that did not appear in class discussion may eventually generate thoughtful insights at exam time—or even years later.