1. Introduction

The US paper industry has been contracting since 2000 due to significant declines in demand due to technological change that has displaced the use of paper in communication. Moreover, the US paper industry has been facing increased competition from emerging paper suppliers globally including China, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Australia, Vietnam, and Russia. The dramatic decline in demand for paper combined with increased import competition has led paper and wood producers to pursue trade remedies through the US Department of Commerce (USDOC) on a range of products with a number of different countries. The US has initiated anti-dumping (AD) and/or countervailing duties (CVDs) on uncoated paper from Canada (see Beaulieu, Reference E2018); uncoated paper from Australia, Brazil, China, Indonesia, and Portugal; as well as the well-known use of AD and CV duties on softwood lumber (see Horn and Mavroidis, Reference Horn and Mavroidis2005, Reference Horn and Mavroidis2006; Bown and Sykes, Reference Bown and Sykes2008; Feldman, Reference Feldman2017). In September 2009, three American paper companies, NewPage Corporation, Appleton Coated and SappiNorth America, and the United Steelworkers (USW) filed ‘unfair trade cases’ against China and Indonesia on imports of coated paper. Coated paper is a high-quality paper used for print graphics for catalogues, books, magazines, cards etc. and paperboard used for packaging. The US–Coated Paper (Indonesia) case highlights some important legal and economic challenges of CVD investigations and the establishment of a ‘benefit’ in subsidy determinations.

The USDOC initiated AD and CV duty investigations on certain coated paper (CCP) from Indonesia and China on 20 October 2009. Following investigation and final determinations by USDOC and the US International Trade Commission (USITC) a CVD of 17.94% was imposed on all Indonesian exporters of CCP to the US on 17 November 2010. The USDOC found that the Government of Indonesia (GOI) provided subsidies to CCP producers in three forms: (1) the provision of standing timber on government-owned land for less than adequate remuneration; (2) the ban on log exports, thereby effectively entrusting or directing log producers to provide log and chipwood inputs to pulp and paper producers for less than adequate remuneration; and (3) debt forgiveness by allowing a CCP producer, through its affiliate, to buy back its own debt from the GOI at a discounted rate. Although the USITC did not find material injury, it did find that these subsidized CCP imports threatened to cause material injury to US producers. Indonesia challenged several aspects of the findings before a WTO panel under the Anti-Dumping Agreement (ADA) and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCMA);Footnote 1 however, this paper focuses on its challenge to the subsidy determination and, in particular, the determination of a ‘benefit’. These findings raise fundamental economic and legal questions about how subsidies are established and measured; and the purpose of the rules on CVDs in the SCMA.

For a ‘subsidy’ to exist under SCMA, it is not sufficient that a government provides a ‘financial contribution’ but it must be established that the financial contribution confers a benefit such that the recipient of the financial contribution is ‘better off’ than it would have been absent the contribution.Footnote 2 A key challenge is how to define and measure ‘benefit’ in order to establish the existence of a subsidy and set the maximum CVD that may be applied in response to the injurious effects of the subsidy.

SCMA Article 14 is not precise and only offers guidelines for calculating the benefit to the recipient relying on market-based benchmarks as comparators. The determination of a benefit is made by establishing whether the terms provided by the government are more favorable than those the recipient could otherwise have obtained on the market.Footnote 3 The extent of the benefit, and therefore subsidy, is determined as the difference between the government terms and the market terms. What kind of ‘market’ provides the benchmark is a contested issue.

An investigating authority needs extensive information regarding the market conditions in the country providing the alleged subsidy and the facts surrounding the government action. For this purpose, voluminous information is typically requested from the investigated parties: the subsidizing Member and the subsidy recipients. Where requested information is not provided, investigating authorities may rely on other ‘facts available’ to fill gaps in the factual record, in some cases leading to outcomes less favorable to a non-cooperative respondent. When and how this possibility may be used is controversial.

Indonesia did not dispute the existence of a financial contribution but only the finding that a ‘benefit’ was thereby conferred.Footnote 4 Indonesia argued that USDOC's finding that the provision of standing timber and the log export ban conferred a benefit violates SCMA Article 14(d) because USDOC made a per se determination of price distortion based solely on the predominant market share of government-owned forests. USDOC had therefore calculated the benefit from lumber supply in Indonesia using the price of Malaysian log exports as a benchmark, claiming there was no market-determined in-country price. Indonesia further argued that the reliance by USDOC on adverse inferences to find the existence of a benefit in the form of debt forgiveness violates SCMA Article 12.7. USDOC established that debt buyback had occurred by inferring an affiliation between the debtor, a producer of CCP that was the sole respondent in the CVD investigation, and the buyer of the debt. Affiliation was inferred using adverse facts available to fill a gap in the factual record regarding the relationship between the two companies. Indonesia's challenges to USDOC's benefit determinations based on the rejection of in-country prices and the reliance on adverse inferences were rejected by the WTO Panel. Indonesia did not appeal the decision.

We discuss the findings related to the determination of ‘benefit’ for purposes of establishing the existence and extent of a ‘subsidy’ under SCMA. We examine the determination of the benchmark price when a government is the sole or predominant owner of a natural resource. We focus on the question of the relevant ‘market’ that forms the benchmark for this analysis, and its link to the aim of SCMA disciplines. We then assess the panel's findings on the use of ‘adverse facts available’ against an allegedly non-cooperative respondent in the determination of ‘benefit’. We explore the purpose of the ‘facts otherwise available’ provision and discuss under what conditions and in what manner investigating authorities may rely such provision to fill gaps in the factual record to the disadvantage of a respondent. We conclude by reflecting on the wider implications of the case.

2. The Context

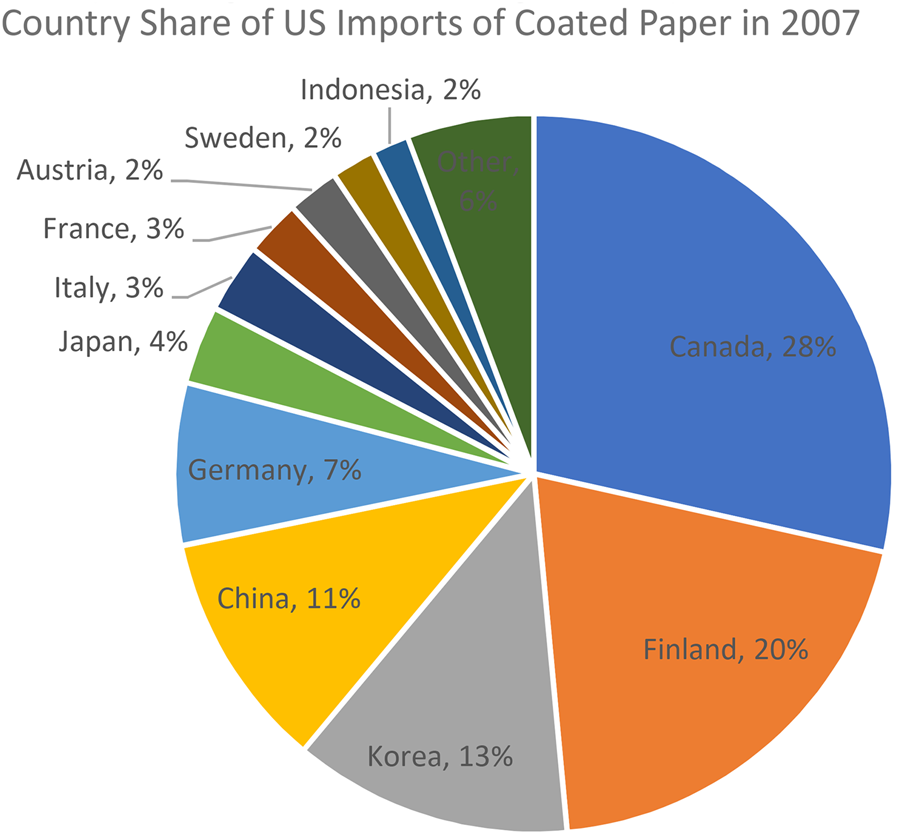

The US paper industry has been challenged by weakened demand and increased import competition over two decades. Although we focus on the CCP case, drop in demand and import competition affected both the paper and wood producing industries, resulting in trade remedies being pursued across products and countries. Figure 1 indicates US paper production has been in decline since 2000. The reduction in newsprint and CCP production was driven in large part by a decline in demand for paper and was exacerbated by the financial crisis in 2008/09. Zhang and Nguyen (Reference Zhang and Nguyen2019) found that demand for paper declined due to increased on-line activity associated with increased online communications and due to the decline in US GDP, which affected demand for paper products. US production of newsprint started dropping dramatically in 2000 and as did CCP production but it then leveled off before declining significantly in 2008. Honnold (Reference Honnold2009) and the USITC (2010) found that the demand for CCP in the US decreased by 21.3% in the period 2007–2009 due to the 2008–2009 recession.

Figure 1. US Paper production 1990 to 2018 (metric tonnes)

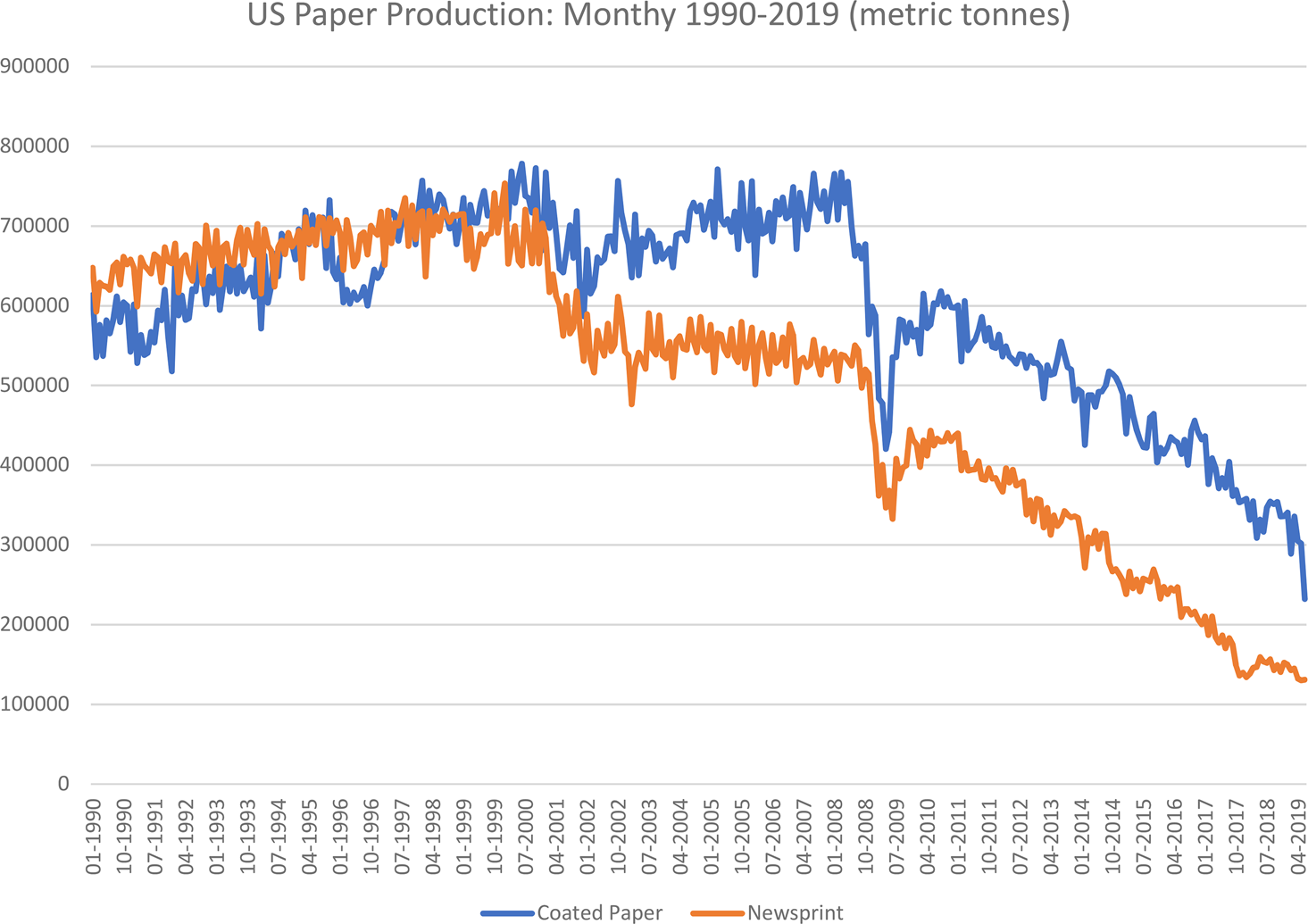

In addition, the US industry has faced a significant increase in imports from the emerging lower-cost paper producers globally. Although there are many types of paper, economically, paper products are considered commodities because there is a high level of substitutability between paper sources. Therefore, paper producers compete on price and this has opened the door for the emergence of lower cost suppliers from countries such as China and Indonesia. Figure 2 shows that CPP imports from China and Indonesia have increased dramatically since 2000, especially China, but Indonesia also significantly expanded CCP exports to the US. Shapiro and Pham (Reference Shapiro and Pham2011) argue that paper production in China and Indonesia expanded with growth in demand for paper in those countries as their share of world paper consumption increased from 2.1% in 1970 to 25.3% in 2009 and their share of production increased from 1.7% to 25.6% of world total. However, Indonesia's dramatic expansion of paper production was also driven by targeted government industrial policy and export-oriented industrialization. van Dijk and Szirmai (Reference van Dijk and Szirmai2006) argue that paper manufacturing was a key sector in the Indonesian transformation from an import-substitution regime to the export-orientation industrialization approach in the New Order regime of the Suharto government of the mid-1980s.

Figure 2. US imports of coated paper from selected countries

The industrial policy provided large tracts of tropical hardwood land at very low concession costs for the establishment of industrial tree plantations allowing clear-cutting and providing plantation subsidies, discounted loans from state-owned banks, and tax deductions resulting in raw material costs in Indonesia at 20–30% of those of US producers. The policy led to tremendous growth in the Indonesian paper industry but also contributed to one of the largest reductions in forestland in the world (second only to Brazil). The World Bank (2001) and Abood et al. (Reference Abood, Lee, Burivalova, GarciaUlloa and Koh2015) analyze forest losses in Indonesia and Abood et al. (Reference Abood, Lee, Burivalova, GarciaUlloa and Koh2015) find that fiber plantation (i.e. pulp and paper production) and logging concessions accounted for the largest forest loss in Indonesia with the oil palm industry coming in second.

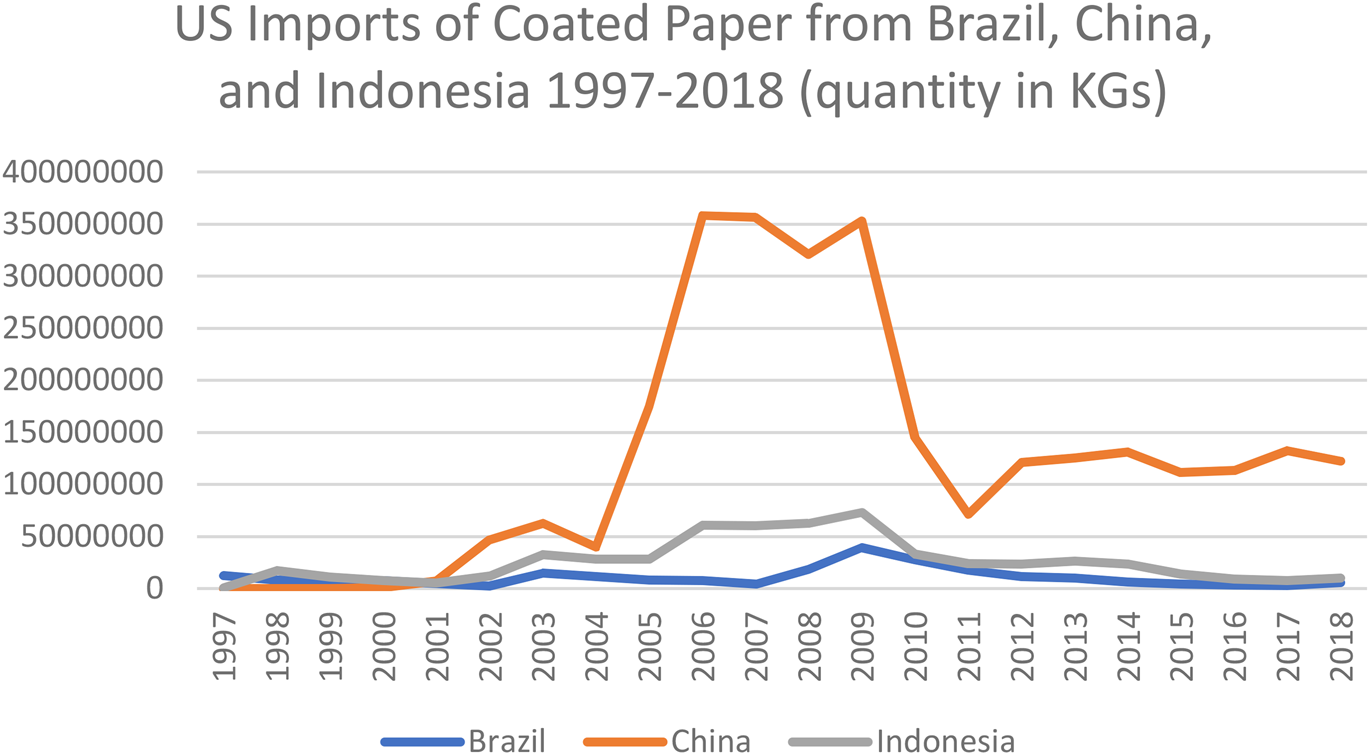

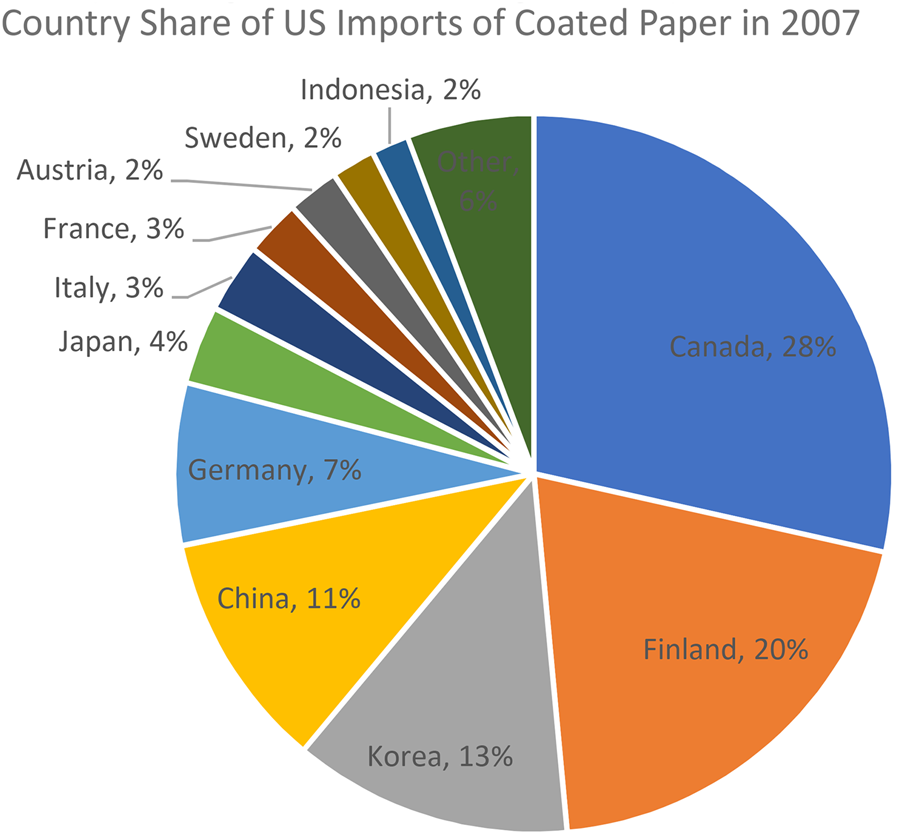

Indonesia's paper industry was a pillar of the government's industrialization program and the subsidies and support for the industry led to low cost paper supply and rapid growth in production and exports. However, there are two key facts of US imports of Indonesian CPP that are important for this case. First, although US imports of Indonesian CPP increased dramatically, Indonesia never reached higher than the 11th largest import source and, at its peak, Indonesia only supplied 2% of US CPP imports (Figure 3). Second, even though Chinese and Indonesian imports increased dramatically, the imports from these countries displaced imports from other countries and the US industry continued to be the main supplier of paper in the US. The USITC found that US producers accounted for the largest share of US consumption and this share increased over the investigation period from 60.7% in 2007 to 65.5% in 2009.

Figure 3. Country share of US imports of coated paper in 2007

Related to this second point, the USITC did not find material injury from CCP imports from Indonesia and China but it did conclude that there was a threat of injury. The US industry increased its market share at the same time as the increased imports from China and Indonesia. However, US paper and lumber producers and labour unions initiated several AD and CV investigations to try to protect their industry from what they saw as unfair import competition. The USDOC and USITC responded with duties on a variety of paper and wood products from several countries. Shapiro and Pham (Reference Shapiro and Pham2011) point out that this is part of a general trend in the US and Europe where industries seek protection through AD and CV investigations in the face of adverse economic conditions. The evidence suggests that politically well-organized industries and labor unions often succeed in winning such protection.Footnote 5

3. Benchmarking with Predominant Government Ownership

The GOI owns 99.5% of forestland and 93% of standing timber in Indonesia. Therefore, a core issue in this dispute was how to determine a benchmark market price to establish a ‘benefit’ when a natural resource is owned or managed by a government. The question of the appropriate benchmark price was key to assessing USDOC's findings that both the royalty fees on government-owned forestland and the log export ban were subsidies in this case.

USDOC found that the provision of stumpage on government-owned land was a financial contribution in the form of government provision of goods under SCMA Article 1.1(a)(iii). It also found that the log export ban entrusted forestry companies to provide inputs to pulp and paper producers and therefore constituted a financial contribution under SCMA Article 1.1(a)(iv). Surprisingly, Indonesia did not challenge these findings of ‘financial contribution’ but challenged USDOC's finding that these financial contributions conferred a benefit on CCP producers.

Although the existence of a ‘benefit’ is key in the definition of a subsidy in the SCMA, how to identify and measure this is not clearly specified. The Appellate Body (AB) in Canada–Renewable Energy clarified that whether a financial contribution confers a benefit on its recipient ‘cannot be determined in absolute terms, but requires a comparison with a benchmark, which, in the case of subsidies, derives from the market’ (para. 5.164). SCMA Article 14(d) specifies that a benefit is conferred if the provision/purchase by a government is for less/more than adequate remuneration. The adequacy of remuneration must be determined relative to prevailing market conditions for the good or service in the country of provision/purchase. The determination must consider price, quality, availability, marketability, transportation, and other conditions of purchase or sale.

Zheng (Reference Zheng2010: 85) notes that this seemingly straightforward formulation belies the more complicated question of ‘what kind of market’ is meant – the market as it is, or a hypothetical market free of any distortion created by the financial contribution at issue. The answer to this question has significant implications for determinations on the existence and extent of the ‘benefit’, and thus of the subsidy. Qin (Reference Qin2018: 19) points out that the AB in US–Carbon Steel (India) defines ‘market’ and ‘prevailing market conditions’ as the area of economic activity in which buyers and sellers come together and the forces of supply and demand interact to determine prices (para. 4.150). This definition does not achieve clarity in cases of sole or predominant government ownership.Footnote 6 This situation arises in non-market economies but also in many market economies with natural resources. The search for a market-based comparator against which to assess the existence of a benefit is especially complex in these cases.

In US–Carbon Steel (India), the AB held that SCMA Article 14(d) sets the adequacy of remuneration as the ‘lens through which “benefit” must be assessed’ and this involves the selection of a comparator, i.e. a benchmark price against which the government price for the good in question must be compared. The question thus arises, what is the appropriate benchmark price? According to the Panel in US–Coated Paper (Indonesia), Article 14(d) specifies that the benchmark for assessing benefit is prevailing market conditions in the country of provision of the good or service (para. 7.32). Qin (Reference Qin2018: 6) points out that the challenge of looking at the market in the country of provision in determining benefit in the case of government-owned natural resources, such as the forestland in this case, is a well-known circularity problem. As the government is the sole, or predominant, supplier of a good, to compare the remuneration for the good to the market price prevailing in the country would be circular, since the market price would be the price of the good charged by the sole or predominant provider – the government.

To avoid this circularity problem, investigating authorities have relied, for benefit comparisons, on benchmark prices from other countries. In the current case, it was undisputed that GOI owned almost all of the forestland in Indonesia. USDOC therefore used log export prices from Malaysia, excluding exports to Indonesia, as the market price benchmark to assess the remuneration paid by CCP producers for log inputs. On this basis, USDOC established a benefit existed because less than adequate remuneration was paid by CCP producers. Indonesia challenged this, claiming that USDOC's refusal to use market prices of logs in Indonesia was founded on a per se determination of price distortion based solely on the GOI's predominant ownership of forestland.

Policy differences among states, such as public management of natural resources, have been argued to not only be compatible with free trade, but indeed be a primary source of gains from trade (Gagne, Reference Gagné2007: 703). Interestingly, the initial draft of SCMA anticipated the problem and included a provision, Article 14(e), prohibiting a finding of benefit when the government is the sole provider or purchaser of goods or services, unless the government discriminates among users or providers.Footnote 7 The draft provision arguably reflects concern with respecting government policy choices regarding ownership of resources and the comparative advantage arising therefrom. However, this provision was not included in the final agreement because of opposition from Mexico to the non-discrimination aspect of the text. The issue of benchmarking in the case of predominant government ownership, therefore, has evolved in Panel and AB rulings on Article 14(d) in cases involving government-owned natural resources. The practice has been to accept the use of out-of-country prices as benchmarks.Footnote 8

The question that arises in these cases is whether the appropriate ‘prevailing market conditions’ to identify a price for the benefit analysis under Article 14(d) should be those in the existing market in the country at issue, or those in an alternative ‘undistorted’ market. Is the aim of the SCMA, and countervailing duty remedy it provides, the efficient allocation of resources through the pursuit of markets undistorted by government intervention? Or does the countervailing duty remedy pursue the more modest objective of supporting tariff concessions by allowing governments a ‘safety valve’ to protect their domestic producers from the injurious effects of subsidized imports, while accommodating divergent socio-economic policies such as on natural resource ownership and management?

We have some answers in international trade rulings. In US–Softwood Lumber IV, the AB held that when the government is the predominant supplier in a country, domestic prices are likely to be distorted as private suppliers will align their prices with those of the government, justifying reliance on out-of-country benchmarks (paras. 100–103). However, in US–Carbon Steel (India) it held that governments may set prices for public policy objectives, rather than profit maximization and these government prices do not necessarily have to be discarded in determining a benchmark under Article 14(d). It noted that a price may be relied upon as a benchmark under Article 14(d) if it is a market-determined price reflecting prevailing market conditions in the country of provision (para. 4.170). US–Countervailing Measures (China) recognized that government-set prices are not necessarily distorted and that ‘the selection of a benchmark for the purposes of Article 14(d) cannot, at the outset, exclude consideration of in-country prices from any particular source, including government-related prices other than the financial contribution at issue’ (para. 4.64).

Zheng (Reference Zheng2010: 36) notes that the economic logic of using an undistorted market as the benchmark is uncontroversial because from an economic theoretical point of view, undistorted markets allocate resources efficiently and subsidies can be measured through deviations. However, he convincingly argues that economic efficiency is not the aim of CVD law, as even economically efficient subsidies may be countervailed if they cause injury to the domestic industry (p. 49). Instead, searching for an ‘undistorted market’ benchmark in determining benefit gives wide discretion to investigating authorities to disregard in-country prices and employ benchmark prices that result in inflated ‘benefit’ determinations and higher permissible CVDs. This wide flexibility undermines the security and predictability that the disciplines on the use of CVDs are intended to provide. Moreover, Again, this is particularly true in the case of natural resources where governments typically regulate the extraction and use of resources and thereby distort the market.

After examining the previous case law, the Panel in this case recognized that predominant government ownership is not sufficient in itself to justify not using in-country prices for the ‘benefit’ determination. Thus, even though the Panel held that the government's position in the market approached that of a sole supplier of the goods, it considered that an investigating authority still should consider evidence regarding other factors on the record, to establish whether the government exerts market power to distort private in-country prices (para. 7.36). It recalled that the AB in US–Anti-dumping and Countervailing Duties (China) held that, in cases where the government's role as a provider of goods is so predominant that price distortion is likely, other evidence carries only limited weight (paras. 446 and 453). The Panel considered that the situation at issue was just such a case. It was satisfied that USDOC considered features of the market for standing timber in Indonesia beyond the GOI's predominant role in timber supply. It concluded that the predominant government role, the fact that the government administratively set the stumpage fees, the log export ban, the negligible level of log imports, and the ‘aberrationally low’ prices of log imports relative to the surrounding region, were sufficient to justify not using domestic prices as the benchmark for determining the existence of a ‘benefit’. On this basis, the Panel held that an unbiased and objective investigating authority could have reached the same conclusion as the USDOC, that there were no market-determined in-country private prices for stumpage that could be used for benchmarking purposes (paras. 7.53, 7.54, and 7.61).

This finding can be criticized from an economic perspective. The economic theory of resource rents holds that rents paid by suppliers to governments to extract resources, say timber, do not affect the price or the supply of timber because supply is determined by the number of trees available for harvest (Qin, Reference Qin2018: 31). Economists refer to this as perfectly inelastic supply in which case the price is determined by demand. Since the supply is limited by the number of available trees to cut, and is therefore, perfectly inelastic in supply, the price is determined by the demand side of the market. This type of argument was successfully made by Canada in the softwood lumber case.

Qin (Reference Qin2018: 32) argues that stumpage fees, and even more so royalty fees such as the ones applied by Indonesia in this case, are not provision of goods by a government but are rather correctly seen as a resource tax collected on timber harvesting. Governments set the stumpage rate administratively and may do so to pursue particular public policy objectives, such as conservation. Under SCMA, tax rates are only a subsidy if they provide a financial contribution to producers in the form of revenue otherwise due that is foregone by the government. If a single tax rate, or stumpage fee in this case, applies to all timber producers, there is no subsidy under SCMA. Public ownership of the lands and government management of the timber resources are part of the socio-economic system. It should not be considered a subsidy if one country decides to manage its resources differently than another country and the different systems yield different prices of the resource. In fact, this is a likely outcome and is based on a comparative advantage of the resource. This situation is fundamentally equivalent to other system-based comparative advantages – for example, publicly funded national health care.

Even when out-of-country benchmarks are permissible, the investigating authority must explain the basis for determining a benchmark and must ensure that the benchmark – including an out of-country benchmark – relates to prevailing market conditions in the country of provision, and reflects price, quality, availability, marketability, transportation, and other conditions of purchase or sale. This relation to in-country market conditions is very hard to achieve, as recognized by the AB in US–Softwood Lumber IV which warned of the difficulty for investigating authorities to reliably replicate market conditions in one country based on market conditions prevailing in another country (para. 108). However, it nevertheless viewed such adjustments are essential as any comparative advantage would be reflected in prevailing market conditions, and CVDs may only be used to offset a subsidy, not to offset differences in comparative advantage (para. 109). Zheng (Reference Zheng2010: 40) argues that out-of-country benchmarks do not replicate the price that would prevail in an undistorted market in the country under investigation. This view is supported by Horn and Mavroidis (Reference Horn and Mavroidis2005: 240) and Crowley and Hillman (Reference Crowley and Hillman2018). Nevertheless, in this case the USDOC's unadjusted out-of-country benchmark was readily accepted by the Panel with no apparent connection or relation to the country of provision, as was previously done by the Panel in US–Anti-dumping and Countervailing Duties (China). Reliance on out-of-country prices without adjustment has been criticized by Qin (Reference Qin2018: 23) as depriving the subsidizing country ‘of any comparative advantage it may have in the good in question.’ This does not accord with the aim of CVDs under SCMA.

4. Adverse Inferences in the Determination of Benefit

Indonesia challenged the reliance by USDOC on an adverse inference to find that the GOI had provided a ‘benefit’ to Asia Pulp and Paper/Sinar Mas Group (APP/SMG), the sole respondent in USDOC's investigation, in the form of debt forgiveness.Footnote 9 Indonesia claimed that this benefit determination was made in a manner contrary to SCMA Article 12.7, which provides that where any party refuses access to, or does not provide, necessary information within a reasonable period or impedes the investigation, determinations may be made based on ‘the facts available’.

However, employing ‘facts available’ in cases of failure to cooperate with national authorities in trade remedy investigations is arguably one of the ‘most polemical’ issues in international trade rules due to the recent increased and emboldened use of this practice by the US (Updegraff, Reference Updegraff2018: 715). Although it is accepted that investigating authorities must necessarily use facts otherwise available to fill gaps in the factual record from non-cooperation or inability to provide data by respondents, when and how they do so is contentious. This issue is the subject of negotiations at the WTO on the rules regarding trade remedies.Footnote 10

The SCMA does not include any specific rules regulating the use of ‘facts available’. By contrast, the ADA Annex II contains specific provisions which provide rules for the use of the best information available in anti-dumping investigations. In Mexico–Anti-Dumping Measures on Rice, the AB held that it would be anomalous if SCMA Article 12.7 were to ‘permit the use of “facts available” in CVD investigations in a manner markedly different from that in anti-dumping investigations’ (para. 295). It found the rules of ADA Annex II to be interpretative context, limiting an investigating authority's use of facts available in CVD investigations. These rules, and the case law interpreting them, therefore also guide the application of SCMA Article 12.7, at issue in this case.

The controversy surrounding the use of ‘facts available’ centers on the practice of making adverse inferences based on facts available that are most negative to the interests of the non-cooperating party (Andrews, Reference Andrews2008: 16). Updegraff notes that to promote efficiency in trade remedy investigations, there is a need to use adverse inferences to incentivize interested Members/parties to provide the information needed by the investigating authorities in the absence of subpoena power. However, this possibility is open to abuse and may lead to unfair results (Reference Updegraff2018: 711 and 717).Footnote 11 It has been noted that investigating authorities typically request interested parties to submit ‘massive amounts of information within a relatively short period of time’ (Andrews, Reference Andrews2008: 15; Vermulst, Reference Vermulst2005: 147) and that parties seldom manage to do so and mistakes are inevitable (Updegraff, Reference Updegraff2018: 717). This enables investigating authorities to categorize this failure as non-cooperation and to resort to adverse ‘facts available’ to establish the existence of subsidization or dumping, or inflate the calculation of the extent of subsidization or margin of dumping. However, as held by the Panels in China–GOES (paras. 7.226–7.310) and US–Pipes and Tubes (Turkey) (para. 7.190), the purpose of the ‘facts available’ mechanism in SCMA Article 12.7 is not to punish non-cooperation, but to ensure that the failure of an interested party to provide necessary information does not hinder the investigating authority's investigation. In fact, it has been held that selecting adverse facts ‘to punish non-cooperating parties would result in an inaccurate subsidization determination’ (ibid. para., 7.190). Thus, an investigating authority is still required to establish a factual foundation for its determinations.

The provision in the US statute in US–Coated Paper (Indonesia) (19 U.S.C. para. 1677e(b)), explicitly gives USDOC discretion to use adverse facts available against interested parties if they have failed to cooperate or provide deficient information. In other words, if USDOC has several facts available that could replace the missing information, it may choose those most adverse to the interests of the non-cooperating party. The US bases its discretion to resort to adverse facts available on ADA Annex II paragraph 7, which provides; ‘if an interested party does not cooperate and thus relevant information is being withheld from the authorities, this situation could lead to a result which is less favourable to the party than if the party did cooperate’. However, this provision makes no explicit reference to adverse inferences, i.e. the deliberate choice of the facts most prejudicial to the respondent. Instead, it could simply be interpreted to mean that when a party does not cooperate, the duty margin that is calculated due to an investigating authority being forced to resort to facts available might be more adverse to the non-cooperative party than the margin that would have been calculated if the party had cooperated (Updegraff, Reference Updegraff2018: 770–771). In fact, the China–GOES Panel held that there is ‘no basis in Annex II for the drawing of adverse inferences’ (para. 7.302).

While 19 U.S.C. para. 1677e(b) has been challenged ‘as such’ in previous disputes, these challenges failed because the provision is discretionary and could thus be applied consistently with the ‘facts available’ provisions in the ADA and SCMA.Footnote 12 However, the application of the ‘adverse facts available’ provision in a particular case has been found to violate the rules of ADA Annex II.Footnote 13 In the current case, Indonesia's challenge was to the provision ‘as applied’.

This case occurred in the context of the restructuring of the financial sector in the aftermath of the debt and financial crisis in Indonesia (the PPAS program and its successor PPAS-2) where the Indonesia Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA) sold the assets (debt and equity) of the banks it had acquired. USDOC had made a finding that IBRA had sold the debt of APP/SMG, the sole respondent in USDOC's investigation, to an affiliate (Orleans) at a discounted rate. USDOC thus found that a financial contribution existed in the form of debt forgiveness, and that a benefit had been received equal to the difference between the amount of the outstanding debt of APP/SMG and the price Orleans paid for it. The finding that Orleans was affiliated with APP/SMG was made through an adverse inference after USDOC concluded that the GOI had failed to cooperate in providing the necessary information requested by the USDOC in its investigation.

Indonesia claimed a violation of SCMA Article 12.7 on the basis that the conditions for reliance on ‘facts available’ were not met. Further, Indonesia claimed that that the ‘facts available’ relied upon by the USDOC in its determination did not reasonably replace necessary information that the GOI had allegedly failed to provide, as required by Article 12.7.

The Panel had to determine whether the conditions for resorting to ‘facts available’, and in particular those leading to ‘less favourable’ conclusions, had been met, and if so, whether the facts relied upon by USDOC ‘reasonably replaced’ the necessary information that was missing from the record, i.e. when and how ‘facts available’ may be resorted to in the context of the use of adverse inferences.Footnote 14 It is useful to examine the Panel's findings on these two issues to assess whether they respect the balance between efficiency and fairness that the ‘facts available’ mechanism is meant to achieve.Footnote 15

4.1 Conditions for Using Adverse ‘Facts Available’

While the ability of investigating authorities to rely on ‘facts available’ to fill gaps in information ‘necessary’ for their determinations under SCMA Article 12.7 is not dependent on the cooperative or non-cooperative status of the interested Member/parties, only when there is a lack of cooperation does ADA Annex II:7 allow reliance on ‘facts available’ that may lead to a ‘less favourable’ result (AB Report in US–Hot-Rolled Steel (para. 95)). In order to establish whether USDOC was entitled to rely on adverse facts available, it was therefore necessary for the Panel in US–Coated Paper (Indonesia) to determine whether the information requested by USDOC was ‘necessary’ for its determination, and whether the GOI had failed to cooperate in providing the requested necessary information.

The Panel in US–Coated Paper (Indonesia) found that the ‘facts available’ should only be used to identify replacements for the ‘necessary’ information missing from the record, as Article 12.7 aims to overcome the absence of information required to complete a determination, not ‘any’ or ‘unnecessary’ information (para. 7.101). These sensible limits prevent authorities from using any failure to respond to detailed information requests as an excuse to rely on ‘facts available’. They also avoid broad requests for information that disguise a ‘fishing expedition’ whereby authorities try to gather information for future unrelated investigations.Footnote 16 In this case, USDOC had requested information from the GOI regarding debt sales by IBRA to three other companies in the context of its PPAS program. USDOC argued that information showing the extent of IBRA's efforts in other PPAS sales to identify the buyers' ownership and ensure that debtors did not buy back their own debt was necessary to determine the plausibility of the GOI's claims that IBRA acted in the Orleans sale in the same manner as it acted in the other PPAS sales, i.e. that it relied on statements of non-affiliation from the buyer and did not carry out additional verifications. Indonesia argued that the requested information regarding other PPAS sales was not ‘necessary’ to assess the APP/SMG sale and would not have shed light on affiliation because these sales involved different companies. However, the Panel held that in the first instance, it is for the investigating authority itself to determine what information it considers necessary. It found that USDOC reasonably considered that information on other PPAS sales was ‘necessary’ to verify the accuracy of information submitted by the GOI, which did not conclusively establish the identity of Orleans’ shareholders (para. 7.112).

The Panel then examined whether the GOI had failed to cooperate, thus justifying ‘less favourable’ outcomes from the use of ‘facts available’. USDOC had determined a lack of cooperation from the fact that the GOI had not provided all the information requested within the deadlines provided, and had thus relied on adverse facts available to find that Orleans and APP/SMG were affiliated. However, the AB has previously ruled that exceeding the deadlines for providing information does not in itself amount to non-cooperation (US–Rot-Rolled Steel, para. 85), see Raju (Reference Raju2004: 260–291).

Indonesia argued that the application of ‘facts available’ with an adverse inference is permitted only in situations where the party possesses the requested information and withholds it, whereas in this case the GOI had not withheld information but had acted to the best of its ability and cooperated with the USDOC's requests for information by submitting all the necessary information requested. It asserted that the many requests constituted a ‘constantly moving target’, which USDOC used as a pretext for drawing an adverse inference. It also pointed to obstacles to its ability to cooperate, including that IBRA had been dissolved in 2004, its records (which were not in electronic format) had been archived and its employees released.Footnote 17 Indonesia further noted that USDOC had cancelled a verification visit related to the Orleans transaction although the GOI had indicated that former IBRA officials with knowledge of the transaction would be present, and that the remaining requested documents had been located and would be available during verification. USDOC argued that the purpose of verification is not to review new evidence.

Consistent with earlier AB case law (US–Hot-Rolled Steel, para. 99), the Panel held that ‘fails to cooperate’ in Annex II:7 entails more than a mere failure to provide requested information (para. 7.115). Instead, the question is whether the interested party applied its best efforts to provide the requested information. The Panel recognized the AB has established that a high level of cooperation is required of interested parties, who must act to the ‘best’ of their abilities’, it has emphasized that good faith necessitates a balance to be struck between the efforts investigating authorities can expect interested parties to make in responding to questionnaires, and the latter's practical ability to comply fully with all the demands of investigating authorities (para. 7.116). Thus, external factors that prevent an interested party from providing the necessary information requested must be considered. The Panel also referred to the Appellate Body's ruling in US–Hot-Rolled Steel (para. 104) that ‘cooperation’ is a ‘two-way process involving joint effort’ requiring investigating authorities to act to assist interested parties in supplying information (para. 7.117).

It is therefore surprising that, while the Panel recognized that USDOC requested voluminous information from the GOI and that it was clear that the GOI had provided a large amount of this information and had thus cooperated to some extent (para. 7.125), it focused on the fact that some requested information was lacking, namely that pertaining to other PPAS sales, to find that USDOC's determination of lack of cooperation was reasonable (paras. 7.119–7.121). The Panel did not consider the successive requests for information to be unduly burdensome or to create a ‘moving target’. The refusal of USDOC to use the planned verification visits to obtain the necessary information from IBRA officials did not affect the Panel's conclusion in this regard (para. 7.123), despite its recognition that cooperation requires joint efforts to obtain the necessary information. Even considering the obstacles the GOI reported in obtaining the requested information, the Panel found that ‘an unbiased and objective authority could have concluded, as the USDOC did, that the GOI had failed to provide necessary information within a reasonable period, and thereby failed to act to the best of its ability to cooperate in the investigation’ (para. 7.125). This finding does not seem to reflect the understanding of a failure to ‘cooperate’ elaborated by the AB in US–Hot-Rolled Steel and lowers the threshold for reliance on ‘facts available’ in a way that may lead to ‘less favourable outcomes’.

4.2 How ‘Facts Available’ May Be Used

Once it is established that the investigating authority may rely on ‘facts available’ in a situation of a failure to cooperate, the manner in which the facts available are identified and used to fill gaps in the ‘necessary’ information must be assessed. The question whether SCMA Article 12.7, read together with ADA Annex II:7, allows for adverse inferences to replace the missing information is controversial.

In this case, USDOC stated that to avoid rewarding the GOI for its failure to cooperate, the USDOC had selected facts on record that reflected the GOI's non-cooperation, which led to a less favourable outcome. USDOC relied on adverse facts available, namely a couple of sentences in press reports suggesting that APP/SMG was surreptitiously buying back its debt, a statement by an unnamed expert knowledgeable about the debt and financial crisis in Indonesia expressing the opinion that it was likely that Orleans was related to APP/SMG and a World Bank report stating that ‘some IBRA sales allegedly allowed debtors to buy back their loans at a steep discount through third parties’ (para. 7.91). The latter report preceded the sale of the APP group assets, and did not discuss PPAS sales but rather sales of small loans by IBRA (Annex B.3, para. 35). Indonesia challenged the basis for USDOC's adverse inference, arguing that such uninformative and speculative information did not ‘reasonably replace’ the missing information as required by SCMA Article 12.7, and that by relying on it rather than on the documents submitted by the GOI to the USDOC showing no affiliation between Orleans and APP/SMG, USDOC failed to act with ‘special circumspection’ as required by Annex II:7 when investigating authorities rely on information from a secondary source (i.e. when using ‘facts available’).

As noted by the Panel, the AB in Mexico–Anti-Dumping Measures on Rice (para. 293) and US–Carbon Steel (India) (para. 4.416) stressed that an investigating authority must use those facts available that ‘reasonably replace’ the information that an interested party failed to provide, with a view to arriving at an accurate determination by selecting the ‘best information’. This involves a ‘process of reasoning and evaluation’ of the information on the record, and if there are multiple facts from which to choose, a comparative assessment of these facts is needed (AB in US–Carbon Steel (India) paras. 4.418–4.431)). The Panel thus correctly recognized that ‘the use of inferences in order to select adverse facts that punish non-cooperation would not accord with Article 12’. While the AB has accepted that, procedural circumstances, such as non-cooperation, may be considered in deciding which facts available constitute replacements for the missing information, it has established that this and any resulting inferences, may not in themselves form the basis of a determination (US–Carbon Steel (India), paras. 4.426 and 4.468). Instead, determinations under Article 12.7 must be based on facts that reasonably replace the missing information, and not non-factual assumptions or speculation (US–Carbon Steel (India), paras. 4.417 and 4.468).Footnote 18 ADA Annex II:7 requires that information from secondary sources be checked ‘from other independent sources’ where practicable to ascertain the reliability and accuracy of such information.

Nevertheless, the Panel in US–Uncoated Paper (Indonesia) held that the prohibition on punitive use of ‘facts available’ does not mean that failure to cooperate is irrelevant when assessing the information before the authority (para. 7.129). It thus found that, although the GOI had provided factual evidence stating that Orleans was unaffiliated with APP/SMG, USDOC reasonably considered that other factual evidence (the press reports, World Bank report and expert statement) raised doubts as to the veracity of those documents. It held that ‘a sufficiently close connection’ existed between the missing information (regarding other PPAS sales and, indirectly, IBRA's due diligence) and the determination of USDOC based on an adverse inference of the affiliation between Orleans and APP/SMG. It further held that no comparative evaluation of the facts was required in this case, as the question of affiliation is binary “yes or no” so that logically the failure of the GOI to cooperate could only lead to the conclusion that Orleans and APP/SMG were affiliated (paras. 7.132–7.133).

While it may be recognized that the absence of information on other PPAS sales to verify the information provided by the GOI left a gap in the factual record that was arguably necessary to fill, it seems doubtful that the speculative statements relied upon can be regarded as ‘facts’ that ‘reasonably replace’ the missing information. It seems to go against the purpose of Article 12.7 of allowing investigating authorities to come to an accurate determination in the face of lack of information to permit determinations on such shaky foundations. The caution to be used when relying on secondary sources, clearly reflected in Annex II:7 would at the very least necessitate efforts to corroborate such information to allow a factual determination to be made, even in cases of ‘binary’ questions. An automatic adverse finding without a sound factual basis arguably goes beyond what is permitted by SCMA Article 12.7, read in the light of ADA Annex II:7, and smacks of impermissible use of ‘facts available’ to punish non-cooperation, contrary to the purpose of this mechanism. The Panel paid lip service to the need to prevent such use but did not police the limits to the ‘facts available’ mechanism, a regrettable omission. It can be expected to lead to further emboldened reliance on ‘adverse facts available’ under 19 U.S.C. para. 1677e(b) by USDOC to facilitate determination of the existence of a ‘benefit’ and therefore of a subsidy in CVD investigations. Given the potential for abuse of this mechanism, undermining security and predictability for traders, this is a matter for concern.

5. Conclusion

The benefit analysis in cases under SCMA is of critical importance. It reflects the choice of negotiators of this Agreement to ascertain the existence and extent of a subsidy in light of its positive impact on the recipient, rather than on its cost to the government. The understanding of ‘benefit’ should reflect the objective of the SCMA, which, rather than to pursue economic efficiency by striving for perfect market conditions, arguably has the more modest aim of preventing beggar-thy-neighbor policies that disturb the competitive relationship between domestic and foreign producers. Equally, to avoid overshooting this objective, the determination of ‘benefit’ should be fact-based and the discretion of investigating authorities in this regard should be carefully policed.

In this respect, this case has broader consequences in two main areas. First, it highlights problematic issues on the choice of a benchmark price for the determination of ‘benefit’ in cases of government ownership of natural resources. It raises serious concerns regarding the policy autonomy of WTO Members in respect of ownership and exploitation of natural resources. Should predominant government ownership of a natural resource be so readily equated with price distortion, and thus allow in-country prices to be disregarded in the determination of ‘benefit’, and be replaced by unadjusted out-of-country benchmarks? Similarly, should low input prices resulting from government export restrictions be seen as creating a ‘benefit’, and thus as a subsidy for purposes of the SCMA? Or are these situations a form of ‘comparative advantage’ of domestic producers, flowing from legitimate policy choices of governments? These cases illustrate that there is an important gap in the WTO treatment of government policies and interactions between economies with different approaches to natural resources. Zheng (Reference Zheng2010: 45) argues that under the undistorted-market approach to the benefit benchmark, not only is an investigating authority such as USDOC given a free pass to both reject in-country private market prices as distorted and to resort to out-of-country benchmarks that are unreliable proxies.

Second, the Panel's findings on reliance of USDOC on adverse inferences creates significant latitude both in the threshold conditions for turning to ‘facts available’ and the manner in which such facts may be used to fill gaps in the factual record. Bearing in mind the challenges of providing the voluminous information requested by investigating authorities, this latitude creates potential for misuse by allowing investigating authorities to find a benefit, or to inflate the amount of benefit, without sound factual basis. It therefore risks skewing the balance between efficiency and fairness sought by the facts available mechanism.

In conclusion, the Panel in US–Coated Paper (Indonesia) seems to have taken a deferential approach to its assessment of the benefit determination of USDOC, which seems at odds with its recognition that its task is to conduct an in-depth and critical examination of the conclusions of the investigating authority (para. 7.7). Its findings thereby potentially spur the emboldened use by investigating authorities of out-of-country benchmarks and of adverse inferences in their benefit determinations. Neither would be a welcome development, and would further undermine the security and predictability that the disciplines on the use of countervailing measures are meant to provide.