I. Introduction

PANDEMICS have shaped the course of human history, felling tottering empires, altering colonization patterns, and endowing populations with competitive advantages. Depending on the circumstances, they can also restructure labor markets, with potentially far-reaching consequences for inequality and social organization.Footnote 1 Indeed, if the demographic shock imposed by a pandemic is sufficiently profound, it may fundamentally reconfigure the relative bargaining power of labor versus capital. This raises the possibility that pandemics hold implications for the substance and conduct of politics in the long run.

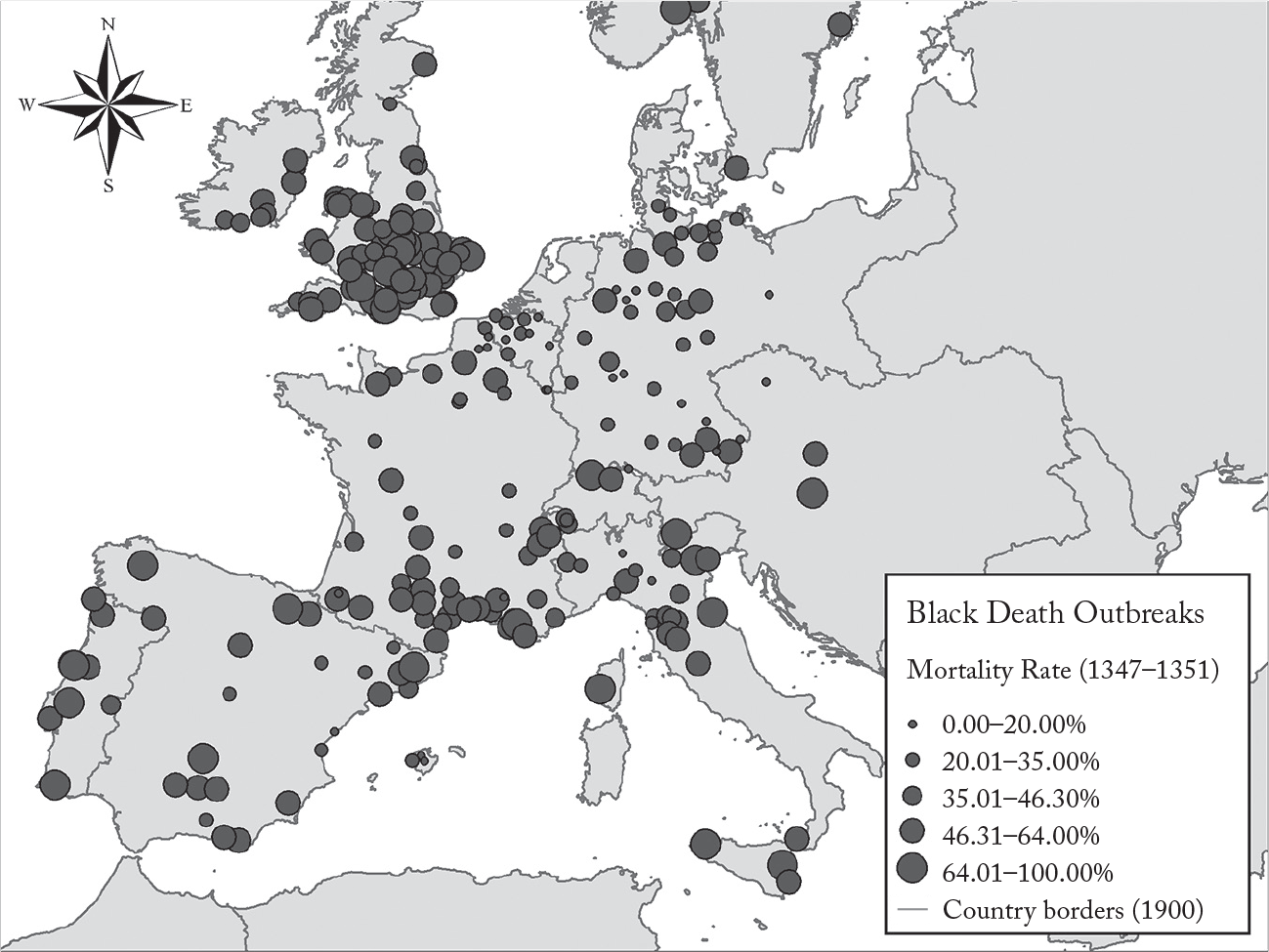

This article examines the long-term political impact of pandemic disease shocks by examining the localized consequences of the deadliest pandemic of the last millennium: the Black Death (1347–1351).Footnote 2 An outbreak of bubonic plague, the Black Death devastated Europe, causing a loss of life estimated at 30 to 60 percent of the total population. Figure 1 shows recorded outbreaks at the town level across the continent, based on data assembled by Remi Jedwab, Noel Johnson, and Mark Koyama.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Recorded Black Death Outbreaks and Mortality Rates across Europe

Among its many consequences, the Black Death radically altered relative factor prices. It left land and capital assets intact but culled the labor force, thus transforming labor from an abundant resource to a scarce one. The economic impact was immediate and long-lasting.Footnote 4 For Western Europe, the pandemic ushered in an era of higher real wages—lasting approximately two hundred and fifty years—and scaled back the obligations imposed on peasants in the manorial economy.Footnote 5

For years, scholars have studied the macrolevel implications of the Black Death for economic development. Economic historians have argued that the Black Death brought an end to the Middle Age’s so-called Malthusian trap, generating a shift from subsistence agriculture to economic production characterized by greater urbanization, increased manufacturing capacity, technological development, and sustained growth.Footnote 6 These changes made possible the fiscal infrastructure needed to support standing armies and to create nation-states.Footnote 7 Given its epochal importance for economic organization, the Black Death is widely considered to have produced one of the most important critical junctures in recorded human history. Indeed, it is thought to be the starting point for what would become large divergences in development between Western and Eastern Europe and between Western Europe and China.Footnote 8

Recently, due to the pioneering data-collection efforts of George Christakos and colleagues, the Black Death’s local-level consequences have also become a subject of scholarly inquiry.Footnote 9 Researchers have traced the long-term consequences of the Black Death for city growth,Footnote 10 the timing of demographic transition,Footnote 11 and the persecution of religious minorities.Footnote 12 Other scholars have examined the more general impact of plague shocks on public goods institutions that shape the accumulation of human capital.Footnote 13 Despite these important advances, the Black Death’s local-level consequences for political organization and behavior have yet to receive systematic social scientific scrutiny.

This inattention to the political legacy of the Black Death reflects a general pattern of neglect within the discipline of political science. Although the Black Death is prominent in accounts of long-term economic development, it has received remarkably short shrift in treatments of the development of political representation and mass political behavior. For instance, Barrington Moore Jr.’s canonical investigation into the social origins of political regimes offers only a single passing reference to the Black Death (for the case of England).Footnote 14 Stein Rokkan’s foundational study of the origins of party politics in Europe ignores it entirely.Footnote 15 The classic political histories of European state formation similarly neglect the Black Death: Joseph Strayer and Charles Tilly only give it offhand mentions in their general discussions of war, city growth, and threats to political stability.Footnote 16 There are exceptions, such as Margaret Peters’s study of the consequences of credit market access for patterns of labor coercion in the aftermath of the Black Death.Footnote 17 But as with earlier scholarship,Footnote 18 her work treats the Black Death as a uniform shock and concentrates its analyses on differences in initial conditions rather than on the variegated impact of the disease.

We part ways with the existing scholarship by focusing systematically on the political implications of geographical variation in the loss of life caused by the Black Death. Our research uses geocoded data on Black Death mortality rates to examine the long-term socioeconomic and political consequences of localized variation in Black Death exposure. The core of our study focuses on the legacies of the Black Death for electoral behavior and land tenure patterns in Imperial Germany during the dawn of mass politics at the end of the nineteenth century. We complement these findings with analyses that assess the effects of the Black Death in earlier and later periods of history. For the pre-Reformation (pre-1517) period, we study the link between exposure to the Black Death and the emergence of early forms of participative institutions. For the period of full-fledged mass democracy (1919–1933), we identify the lingering effects of the democratic cultures bequeathed by the Black Death on geographic patterns of voting behavior in the Weimar Republic.

The historical experience of German-speaking central Europe is especially apt for evaluating the Black Death’s long-term political consequences. Because this area exhibited significant regional variation in the mortality caused by the Black Death, one can identify distinct outcome patterns associated with differing levels of exposure to the outbreak. Equally important, there was no single, absolute ruler or other centralized political regime governing the German-speaking territories at that time. Rather, from the medieval period to the nineteenth century, the German-speaking parts of Europe were made up of a decentralized patchwork of principalities, duchies, free cities, and other administrative units. This high level of decentralization gave local political cultures, borne from the initial reactions to demographic collapse, space to implant themselves and become more distinctive over time.

Our central contention is that the long-lived regional political cultures attributable to the Black Death significantly shaped patterns of political participation up until the early days of the German Empire’s foundation, and held a weaker but still perceptible influence in the decades that followed. There are three steps in our argument.

First, differences in Black Death mortality led to differences in the persistence and depth of labor coercion during the early modern period (mid-fourteenth century to the late eighteenth century). In areas where the Black Death hit hard, elites were forced to abandon serfdom for an incipient free labor regime. By contrast, in areas where the Black Death’s toll was relatively mild, customary labor obligations were maintained (or even amplified).

Second, regional differences in the use of labor coercion led to a divergence in socioeconomic and political organization. In areas where serfdom receded, the new freedoms granted to laborers encouraged the development of institutions for (limited) local self-government, produced more employment outside of agriculture, and led to greater equality in landholding. In areas where serfdom was maintained or became more onerous, the development of participative institutions for local self-government was inhibited, the agricultural economy remained dominant, and high levels of inequality in landholding persisted.

Third, with the advent of mass electoral politics in the late nineteenth century, the societal conditions generated by the distinct legacies of labor coercion shaped voters’ electoral decisions. In the areas characterized by participatory institutions and relative equality, voters were inclined to reject the guidance of traditional elites, leading to weak support for conservative parties and to stronger support for liberal parties. Contrariwise, in the areas characterized by less inclusive institutions and high inequality, voters were more inclined to defer to the directives of traditional elites, leading to strong support for conservative parties and weaker support for liberal parties. To put it succinctly, strong Black Death shocks favored abbreviated experiences with serfdom, more selfgovernment, and ultimately, receptiveness to horizontally oriented and inclusive political parties. Weak Black Death shocks favored prolonged experiences with serfdom, less self-government, and eventually, receptiveness to parties with a hierarchical and illiberal orientation.

Our empirical findings match these expectations. Using district-level electoral data from the 1871 legislative elections of Imperial Germany, we find that geographical variation in exposure to the Black Death is decisively and negatively related to the percentage of the vote won by the Conservative Party—a party that was strongly antidemocratic in its means and ends. Moreover, our research shows that areas least affected by the Black Death were characterized by societal conditions in which the Conservative Party was likely to thrive. In particular, we find that landholding inequality in the late nineteenth century was significantly greater in areas with mild exposure to the Black Death than in areas where the disease had a profound impact.Footnote 19

Our complementary analyses support the mechanisms and the implications of our argument. The analysis of the pre-Reformation period provides evidence for our claim that the intensity of Black Death exposure was positively associated with subsequent changes in key aspects of political development. Specifically, we demonstrate that the hardest hit areas were more likely to adopt local participative elections in the period from 1300 (pre-Black Death) to 1500 (post-Black Death) than areas that were not similarly affected. This gives us confidence that the Black Death encouraged the development of distinctive regional political traditions that shaped political behavior in the long run.

The analysis of the Weimar Republic, in turn, provides evidence that the link between Black Death exposure and support for illiberal parties is not an artifact of the political idiosyncrasies of early Imperial Germany. Examining spatial variation in the vote share of the Nazi party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, nsdap) in the 1930 and July 1932 German federal parliamentary elections, we find that areas that had experienced high levels of exposure to the Black Death showed significantly lower levels of electoral support for the Nazis than did areas with low levels of exposure. This gives us confidence that the regional political traditions we attribute to the pandemic were robust and played a crucial role in German electoral politics during pivotal moments in the nation’s history.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: First, we outline our contribution relative to existing studies of labor coercion and the longterm consequences of infectious diseases. Second, we offer a theory of how the Black Death affected relative factor prices and the feasibility of labor coercion. Third, we introduce the empirical case and highlight the dimensions most relevant to our study. Fourth, we outline the framework of our empirical test. After discussing the results, we conclude and consider the possible lessons of our study.

II. Pandemics, Factor Prices, and Labor Coercion

Pandemics impose death, often on a massive scale. Whenever a pandemic causes a major demographic collapse, it can also change relative factor prices: the economic returns to labor versus land or capital. This may lead to substantial changes in economic and political organization. It is widely acknowledged that differences in factor prices shape economic inequality,Footnote 20 which, in turn, affects both the incidence of democracyFootnote 21 and the quality of democratic representation.Footnote 22

Even though factor prices are axes of social organization, it can be a challenge to pinpoint empirically how they shape political life. As relative factor prices delimit the bargaining power of social groups, they shape and are shaped by public policies.Footnote 23 The same can be said for political institutions, which structure how public policies are made.Footnote 24

Because the causal arrow relating factor prices to policies and institutions goes in both directions, isolating the influence of the former requires one to identify an appropriate exogenous shock. The Black Death offers a good historical example of such a shock. The plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. During the Black Death outbreak that is at the center of this study, it was transmitted to humans by infected fleas carried by rats (and later via human-to-human contact in its pneumonic strain). But its etiology was completely unknown to medicine at that time,Footnote 25 so its timing and intensity did not appear to depend on differences in rudimentary public health procedures or on preexisting levels of economic development.Footnote 26 Proximity to trade routes was clearly important, but conditional on trade exposure, plague mortality was nearly random.Footnote 27 Unlike contemporary pandemics, the Black Death did not overtly discriminate by social status: it cut down wealthy and poor alike, claiming the lives of the King of Castile, large swathes of the clergy, and countless peasants. At the same time, the intensity of the disease varied greatly across geographic areas.Footnote 28 These special features make it possible to discern the long-term influence of Black Death mortality, and ipso facto, changes in relative factor prices, by employing a standard suite of econometric tools.

Our central claim is that by increasing the price of labor relative to land, Black Death mortality shaped patterns of labor coercion and the long-term development of local political cultures. Extant studies offer two competing approaches for considering the starting point of this argument: the effect of changes in factor prices on labor coercion.

The standard account can be classified as the theory of Malthusian Exit. According to this view, shocks that generate a high level of labor scarcity (thus increasing labor’s shadow price) catalyze a series of economic and social changes that move a society away from a subsistence economy based on labor coercion and toward an economy with manufacturing potential based on free labor.Footnote 29 Specifically, the scarcity of labor improves the outside options of workers and forces elites to reduce coercive practices, which in turn creates greater and more variegated forms of consumption. As demand for manufactured goods increases, new technologies develop, urban areas expand, and the power of landed elites begins to wane. This theory is often invoked to explain Western Europe’s development in the wake of the Black Death.

An alternative account can be classified as the theory of Elite Reaction, according to which elites respond to an increase in labor scarcity by doubling down on coercion.Footnote 30 In particular, elites use more coercion to repress the wage increases and improved living standards that would otherwise follow a reduction in labor force size. Work obligations and the policing of labor only become more burdensome. The agrarian economy remains supreme, technological innovation is suppressed, and the power of landed elites remains uncontested. This theory is often invoked to explain the recrudescence of serfdom and economic underdevelopment in Eastern Europe after the Black Death.Footnote 31

Empirical studies that address each theory’s relative purchase are limited and offer contradictory findings.Footnote 32 In truth, much of the existing empirical work provides little guidance for understanding the consequences of a labor market shock like that generated by the Black Death. This is because previous contributions largely seek to assess the consequences of variation in relative factor prices along the intensive margin—that is, for small amounts of change within the respective society. The Black Death, by contrast, generated change along the extensive margin. Indeed, at an aggregate level it was one of the largest—and possibly the largest—labor market shocks in recorded human history. As we argue in the next section, the depth of labor scarcity is important for understanding the elite reaction to a labor supply shock. Reactions to minor shocks will differ from reactions to large ones.

The empirical findings of this article about the long-term legacy of the Black Death contribute to a prominent literature on the economic and political consequences of infectious diseases. The incidence of infectious diseases has been tied to low levels of labor productivity and investment, and ultimately to the emergence of poverty traps in tropical areas.Footnote 33 In the case of colonial Mexico, disease-driven demographic collapse has been linked to long-term changes in land tenure patterns.Footnote 34 Diseases may also determine the composition of the ruling elite and the prospects for good governance. According to Jared Diamond, Europeans gained immunological advantages by living in proximity to livestock (and suffering through repeated disease waves), and this partially explains the ease with which they were able to conquer the Americas.Footnote 35 Most directly related to our article, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson show that the disease environment at the time of colonization shaped the institutions that colonizers implanted in different territories, thereby influencing the quality of government and prospects for economic development.Footnote 36 Our study provides a natural complement to this finding. Whereas Acemoglu and colleagues demonstrate that diseases can affect political development via the external imposition of institutions, we demonstrate that diseases can also catalyze processes of institutional change that are internal to societies.

In examining how demographic change reshapes social and political organization in agrarian societies, this article also contributes to the study of landed elite power and its implications for democracy. Historical investigations of political change have long emphasized that the economic and political power of landed elites tends to delay or preclude the transition to democracy.Footnote 37 And for countries that have already made the transition, the presence of a powerful landed elite fundamentally shapes the character of electoral politics.

Practices like clientelism and vote brokerage are considered especially effective in contexts where landed elites employ a large segment of the labor force.Footnote 38 Consequently, in agrarian settings with dominant landowners, voters are often induced to vote for candidates preferred by the elites—typically, conservative politicians inclined to defend the extant property-rights regime.Footnote 39 Our contribution to this literature is to endogenize the sources of landed elite power in a long-term historical perspective. Specifically, we show how shocks to the labor supply can undermine the landed elite’s political influence. In the process, we offer a novel account of the historical genesis of programmatic versus clientelistic linkages between citizens and politicians.Footnote 40

This article also contributes to the literature on how patterns of labor coercion shape political development in the long run. Influential treatments of the subject have long held that traditions of servile labor inhibit state building or dampen the prospects for democracy.Footnote 41 Following in these footsteps, a recent wave of empirical scholarship explores how legacies of labor coercion shape norms and political behaviorFootnote 42 as well as patterns of economic activity.Footnote 43 Our work follows this scholarly agenda, in that it seeks to deepen understanding of the political consequences of the erosion of serfdom by tracing out the repercussions of a plausibly exogenous shock to this institution: mortality due to the Black Death.

III. The Long-Term Implications of Labor Supply Shocks for Electoral Behavior

In this section, we explicate the theoretical mechanisms tying labor supply shocks to long-term electoral behavior. We start with the premise that the magnitude of the initial shock is crucial. If a labor supply shock is sufficiently profound, it creates a new institutional equilibrium that recasts the relationship between lord and peasant, producing more inclusive modes of political engagement that in the long run structure mass political behavior. Weaker labor supply shocks lead to a retrenchment of socioeconomic hierarchies and obligations, producing exclusionary modes of political engagement that also structure mass political behavior, albeit in a very different way.

Consider the relationship between labor supply shocks and labor coercion. A demographic collapse that radically reduces the labor supply brings two immediate consequences. First, the shadow price of a coerced worker’s labor skyrockets. The economic returns for work outside the manor to which the laborer is bound become much greater, making employment elsewhere significantly more attractive and increasing the laborer’s willingness to accept the risk of punishment that results from fleeing the manor. For the elites, keeping what remains of the labor force in place requires either an increase in wages (and a reduction in customary obligations) or a greater investment in the monitoring and punishment of laborers. Given the existence of economies of scale in policing labor, the per-laborer cost of dissuading exit through coercion will be exorbitant. Therefore, unless the shock causes labor productivity to increase immensely, the elites will consider adopting an incipient free-wage regime to be the least detrimental option.

The second consequence of a negative labor supply shock concerns the prospects for coordination among agrarian elites. Given the reality of a decimated labor force, the competition among elites for laborers will be quite intense: success or failure in poaching the labor of neighboring manors may mean the difference between bringing a crop to harvest or watching it rot in the fields. So, to keep wages low and laborers on their estates, elites must expend significant effort to create and police an antipoaching cartel among themselves. But the larger the shock, the greater the returns for each member of the elite who defects from the cartel. Thus, for a sufficiently large shock, maintaining the antipoaching cartel will be next to impossible. An incipient free wage regime emerges by default.

If the shock to the labor supply is fairly minor, the dynamics will differ. With only a moderate reduction in the labor force, the returns to laborers from fleeing their manors will be smaller, and the per-laborer cost of dissuading exit through coercion will be much more manageable for elites. And given the smaller returns to elites from poaching the laborers of their peers, it will be feasible to sustain a cartel. Consequently, whereas large labor supply shocks will prompt an early exit from labor coercion, smaller shocks will be associated with its persistence or reinforcement.

In turn, the abandonment or persistence of labor coercion has implications for economic, social, and political organization. In settings where labor coercion has diminished, the freedom of movement for laborers contributes to greater urbanization as well as to a restructuring of relationships in the countryside. Greater urbanization and higher living standards spur the development of new technologies that jumpstart new forms of manufacturing, such as textile production and book printing with movable type. Overall, the weight of agriculture in the economy diminishes. Agricultural production itself shifts away from the classic manorial model in which land and property rights are vested solely in elites, to one in which land rights are more widely shared. The roots of a system of small farming are established, and formerly gaping inequalities in landownership become more modest.Footnote 44 The improved employment opportunities and diversification of property rights naturally lead to a more heterogenous social structure and more diverse preferences among the populace. The new social groups, in turn, demand channels for the representation of their interests. At the local level, this leads to the development of such institutions as the election of mayors and town councils, providing at least a limited form of self-government. Even if traditional elites initially hold veto power over the decisions of these institutions, their very existence encourages nonelite coordination and demand-making.Footnote 45 Thus, the seeds for autonomous political participation are sown.

In settings where labor coercion persists unabated over a long period of time, these occurrences do not come to pass. Peasants remain tied to the land, and urban areas remain small and scarce. The adoption of technological innovations, to the extent that these emerge from elsewhere, is actively discouraged by the traditional elites. Political power remains vested in the landed aristocracy, which perpetuates its status through the use of enforcers deployed to police labor. The economy gravitates around agriculture, which is dominated by a small number of large landholdings. Institutions designed to channel the demands of nonelite actors are unlikely to emerge—and if they do, they perish quickly. The great mass of the citizenry gains little or no experience in advocating for their own interests, and most certainly not in a way that might conflict with the desires of the agrarian elite. In this context, the prospects for autonomous political participation are dim.

The divergent paths of labor coercion that emerge in the wake of labor supply shocks create very different environments for electoral politics once the era of mass politics begins. Areas where labor coercion was dismantled early differ in four crucial ways from those areas where it persisted over time. First, early reforming areas have more differentiated economies, giving more voters viable employment opportunities outside their current jobs. As a consequence, voters are not so easily intimidated by employers who wish to sway their votes.Footnote 46 Second, the opportunities afforded to laborers in early reforming areas encourage greater human capital development, especially higher levels of education. As a result, voters are more likely to be politically engaged and more aware of their political options, with a keener sense of how the contenders represent their interests.Footnote 47 Third, because of the legacies of labor coercion for urbanization, voters in early reforming areas are likely to live in more densely populated communities than voters in late reforming areas. Greater population density makes it harder for traditional elites to monitor and profit from clientelistic exchanges, thereby limiting the influence of material inducements on voting patterns.Footnote 48 Fourth, and arguably most importantly, the erosion of traditional socioeconomic hierarchies in early reforming areas means that voters in these areas are less likely to adhere to norms dictating deference to elites. Among such norms are shared understandings of reciprocity, which facilitate the ability of local elites to guide voters’ electoral choices.Footnote 49 Seen more broadly, deference norms reflect political cultures in which citizens view themselves as the subjects of political and economic elites—a state of affairs conducive to the growth of illiberal and antidemocratic political movements.Footnote 50

To summarize, the societal context bequeathed by the early erosion of labor coercion is one where in the long run, voters (1) have a clear sense of which candidates they would prefer to vote for, and (2) enjoy the economic and cultural autonomy to vote as they wish. In contrast, the societal context bequeathed by the late or incomplete erosion of labor coercion is one where voters ultimately have no strong preferences over contending political forces, and lack the wherewithal to resist the voting instructions of traditional elites. Figure 2 summarizes the theory.Footnote 51

Figure 2. Long-Term Consequences of the Black Death

IV. Background on the Case of Germany

The subject of our empirical analysis is German-speaking Central Europe, an area that was largely contained within the Holy Roman Empire and that remained politically fragmented for most of the time period under consideration. Because the Holy Roman Empire was a confederation—as opposed to a centralized nation-state—this area should be understood as a cultural entity, united primarily by a common language and shared customs.

Rationale for Case Selection

We focus on this particular area for two reasons. The first is the significant regional variation in the Black Death’s intensity. Much of Germany’s west, and southwest, and parts of the north suffered devastating outbreaks, while many towns and settlements in the eastern parts were relatively unaffected.Footnote 52

The second reason is Germany’s historically high level of political decentralization, which allowed local traditions to persist over extensive periods.Footnote 53 Germany was long composed of hundreds of principalities, city-states, kingdoms, and other administrative units. In other settings, a central state was able to supplant local institutions, but in Germany distinct local political traditions had ample space to survive until at least the nineteenth century. This combination makes Germany the ideal case for studying the pandemic’s long-term effects.

Imperial Germany: Socioeconomic Conditions and Political Outcomes

In 1871, Prussia united most of the German cultural region under a single political system known as Imperial Germany or the German Empire. Based on our theory about the social transformation brought by the Black Death, we use this case to investigate long-term variation in fundamental socioeconomic structures and local political behavior.

In terms of socioeconomic structures, we focus on landholding inequality. Where land inequality is high, a small number of landholders own a disproportionate share of property in the agricultural sector, indicating that it is more elite-dominated. This elite domination of rural property rights is often associated with elite domination of politics.Footnote 54

In terms of political behavior, we consider electoral outcomes in elections of the Imperial Diet (the Reichstag), the lower chamber of the Empire’s legislature. Importantly, the formal conditions (electoral rules, voting age, and suffrage restrictions) were homogeneous across Germany, making these elections suitable for cross-sectional analysis. We concentrate on two outcomes: (1) the vote share received by the Conservative Party in 1871, and (2) the number of electoral disputes between 1871 and 1912, indicating violations of electoral rules (typically by elites). Such disputes arise when formal democratic procedures are undermined in some way, indicating a violation of democratic principles.Footnote 55

We focus on the Conservative Party of the early 1870s because it was elitist in both means and ends. Its stated goal was to defend traditional social structures—that is, the privileged position of the landed elites. It rejected popular democracy, resisted the socioeconomic changes caused by industrialization, and railed against national unification (which was perceived to threaten the aristocracy).Footnote 56 Although the Conservative Party ran in formally democratic elections, the landed elites used intimidation, clientelism, and worker coercion to improve their chances of victory.Footnote 57

Such tactics demonstrate that while formal electoral regulations were the same across Germany, socioeconomic conditions and political norms varied significantly.Footnote 58 This diversity also led to variation in the parties that ran across different districts.Footnote 59 The electoral viability of the Conservative Party depended on the socioeconomic and political structures associated with an agriculturally centered economy and high landholding inequality.Footnote 60 In places where these conditions did not exist, the party had little chance of success in open electoral competition, so party organization was scarce.Footnote 61 There was another conservatively oriented party: the Free Conservative Party, whose leadership, unlike that of the Conservative Party, included industrialists who did not defend an estate society. Moreover, besides several smaller parties that competed only in geographically limited areas, four other major moderate/liberal parties were present across large areas of Imperial Germany in the early 1870s: the National Liberal Party, the German Center Party, the Liberal Reich Party, and the German Progress Party.

Our historical perspective on the social bases of parties’ electoral support aligns with previous scholarly work. Most importantly, Rainer Lepsius argues that parties in nineteenth-century Germany reflected “sociomoral milieus”Footnote 62 based on such deeply rooted factors as culture, socioeconomic conditions, and political norms.Footnote 63 Note that the variation in these dimensions predated the Empire’s political system.Footnote 64

We focus initially on electoral outcomes in 1871 because, with national unification just beginning, local political traditions were not likely to have been much affected by national-level trends. But in the following section we consider the Weimar Republic’s crucial 1930 and July 1932 elections, exploring whether the political-economic equilibria created by differential Black Death exposure persisted into interwar Germany. Moreover, in the supplementary material we consider the results of the 1874 election.Footnote 65

Weimar Germany: Persistence of Local Political Cultures and Votes for the National Socialist Party

Given our contention that different levels of exposure to the Black Death bequeathed distinctive and enduring political traditions that contributed to the electoral viability of illiberal parties, it is worth investigating whether the divergence caused by the outbreak can still be seen in later elections, especially the fateful German parliamentary elections of 1930 and July 1932. Because these elections gave rise to National Socialism as a major force in German politics, their relevance for the course of world history is unquestionable.

Specifically, in 1930, Hitler’s NSDAP expanded its vote share from 2.6 percent to 18.3 percent, increasing its number of seats almost ten-fold, from 12 to 107. This is considered to have been the party’s “breakthrough election.”Footnote 66 And in July 1932, the nsdap became the parliament’s largest party, with slightly more than 37 percent of the vote.Footnote 67

At first glance, a number of factors cast doubt on the proposition that the Black Death’s legacy would still persist in the Weimar Republic. For one, politics in Germany became more nationalized after the 1870s, leading to the development of a national democratic culture.Footnote 68 This may have entailed a move away from the fragmented initial conditions. And after 1871, Germany’s second wave of industrialization took off, followed by comprehensive social transformation.Footnote 69 Among the consequences were changes in electoral politics and a realignment of the party system.Footnote 70

The combination of national trends and World War I likely decreased the influence of regional political traditions that derived from experiences with the Black Death. Yet if the political cultures shaped by differences in the pandemic’s intensity had survived for more than five hundred years, their remnants might still be visible in the Weimar period (1919–1933).Footnote 71

Indeed, several studies suggest that Weimar Germany retained a geographically fragmented electoral landscape, where outcomes were often influenced by local socioeconomic configurations, culture, and traditions.Footnote 72 If conditions differed greatly across geographic areas, it is likely that the Nazis’ potential for electoral success varied accordingly.Footnote 73

Thus, despite the aforementioned trends, regional political traditions generated by differential Black Death exposure may still have affected electoral outcomes in the Weimar Republic. Specifically, John O’Loughlin suggests the following interpretation of spatial differences in the Nazi party’s success:

Weimar Germany was simply a complex mosaic of culturally identifiable microregions, a product of a history of local principalities, weak central authority, and intense political-confessional competition.Footnote 74

Like the Conservative Party of the early 1870s, the Nazi party promoted a political platform that was hostile to democracy and fundamentally illiberal at its core. Although the two parties certainly had crucial differences in terms of their socioeconomic policies, they were similarly explicit in their disdain for competitive elections and a plural social order.Footnote 75 Accordingly, it is plausible that the same Black Deathdriven spatial variation in social hierarchy and prior democratic experience could also have influenced the nsdap’s electoral success.

V. Empirical Design

Measuring the Intensity of the Plague: The Black Death Exposure Intensity Score

Since the Black Death’s impact varied widely across Central Europe and its intensity represents our key explanatory variable, we must construct an appropriate measure of Black Death intensity. To this end, we use data compiled by Jedwab, Johnson, and Koyama on recorded outbreaks in European towns,Footnote 76 primarily based on Christakos and colleagues,Footnote 77 to compute a measure of Black Death exposure intensity (bdei score).

Although we have data on mortality rates for many individual medieval towns, our score is not simply a reflection of the intensity of the outbreak just in the nearest town. Instead, it is a composite measurement accounting for how much the area around any specific location was affected. We compute the score this way to account for the fact that labor is a highly mobile factor of production. If the Black Death has only a minor impact, or only hits a few locations in an area, the labor supply can return to its old equilibrium due to regional market forces.Footnote 78 But if many locations in an area are hit severely at the same time, it is much harder to return to a previous equilibrium. Accordingly, we assign a higher bdei score to any location of interest (that is, any geographic unit of analysis) if there are many outbreaks around it and if these outbreaks are severe. Thus, our score can also be understood as conceptualizing how close any given location was to the pandemic’s center.

Mathematically, the bdei score represents the sum of recorded outbreak intensities inversely weighted by the distance to any specific location. The weighting is inverse (and exponentially decreasing) because outbreaks in the closest vicinity are the most relevant.

Imperial Germany: Outcome Variables

Our analysis of outcomes in Imperial Germany is at the level of the electoral district. We consider three main outcome variables that reflect distinct political-economic equilibria:

SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS

—1. Landholding inequality (Gini coefficient): Measures of landholding inequality, provided by Daniel Ziblatt, are bounded between 0 (absolute equality) and 1 (absolute inequality).Footnote 79 Especially in societies with large agrarian sectors, high levels of landholding inequality indicate socioeconomic power imbalances, which we expect to be a long-term result of the equilibrium associated with low Black Death mortality.

POLITICAL OUTCOMES

—2. Conservative Party vote share 1871: Data on electoral outcomes are provided by Jonathan Sperber.Footnote 80 These data denote the Conservative Party’s vote share in the 1871 elections. As that party promoted extremely hierarchical social structures and opposed democratization, its vote share directly reflects the equilibrium associated with low Black Death mortality.

—3. Net electoral disputes 1871–1912: Data on electoral disputes are provided by Robert Arsenschek and Ziblatt.Footnote 81 These data reflect the cumulative number of disputes that occurred in all peacetime elections.Footnote 82 Since electoral disputes reflect the subversion of formal democratic regulations, they are more likely to occur in areas without strong democratic traditions, which we attribute to low Black Death mortality.

Imperial Germany: Control Variables

It is crucial to control for factors that could affect both Black Death intensity and subsequent long-term political-economic outcomes. Our geographic controls in particular reflect the importance of trade in disease transmission: the Black Death spread through rat fleas, which are often transported by merchants and commercial ships.Footnote 83

Specifically, our control variables are as follows:

—1. Urban density 1300: Historical levels of urban density could influence both Black Death intensity and long-term political-economic outcomes. We use data by Fabian Wahl to compute a historical urban density score for each electoral district.Footnote 84

—2. Distance to the nearest major port: Besides the fact that the Black Death spread through trade, proximity to major ports could also influence commerce and economic activity in the long run.Footnote 85

—3. Distance to the nearest medieval trade city: This variable is included for the same reasons as (2).Footnote 86

—4. Distance to the ocean: Although major ports were the primary centers of sea trade, there may have been a number of minor ports. Therefore, we include distance to the ocean (North Sea or Baltic Sea) as a proxy.

—5. Distance to the nearest large river: Much trade took place on navigable rivers, likely spreading the plague.Footnote 87

—6. Elevation: Land elevation could affect the accessibility of population centers to outsiders and animals carrying the plague,Footnote 88 influencing both plague intensity and long-term political-economic outcomes.

Weimar Germany: Persistence of Local Political Cultures and Votes for the National Socialist Party

Extending our empirical analysis, we consider the spatial association between Black Death exposure intensities and the NSdap’s vote share in the elections of Weimar Germany.

Specifically, we consider two primary outcome variables:

—1. NSDAP vote share 1930: For this election, data on electoral outcomes at the level of the town/city are provided by Jürgen Falter and Dirk Hänisch.Footnote 89 As the NSDAP was extremely illiberal and antidemocratic, its high vote shares are indicative of the equilibrium associated with low Black Death intensities.

—2. NSDAP vote share July 1932: Data on the outcomes of this election at the county level are also provided by Falter and Hänisch.Footnote 90

We use the same set of control variables as in our main analysis. Peter Selb and Simon Munzert provide the geographic data used to compute them.Footnote 91

Mechanisms, Part I: Pre-Reformation Germany—Introduction of Participative Elections 1300–1500

In addition to our primary analysis, we add a secondary set of empirical tests focused on changes in participative institutions at the town level (1300–1500). These analyses are meant to evaluate empirical support for the suggested transmission mechanisms.

Here, we focus on a binary dependent variable based on data compiled by Wahl: introduction of participative elections 1300–1500.Footnote 92 This variable is equal to 1 for towns that newly adopted local participative elections during the 1300–1500 period; 0 otherwise.Footnote 93 Note that participative elections in medieval Germany did not mean a participatory democracy with full voting rights for all adults. Instead, such elections consisted of contests for the mayor, town council, or other local offices, usually with participation limited to adult male property owners. That said, even these forms of restricted participation indicate important changes in political institutions and norms.Footnote 94

Because our unit of analysis here is the town—an organizational unit that existed long before and long after the time period we investigate—additional covariate data are available. Thus, we account for several factors that could have had an impact on early democratic development.

Specifically, we include variables for (1) land elevation, (2) distance to the nearest river, (3) Roman road in the vicinity, (4) agricultural suitability, (5) population in the year 1300 (log), (6) land ruggedness, (7) urban potential 1300, (8) trade city 1300, and (9) proto-industrial city 1300. We draw these variables from Wahl, who provides detail on coding procedures.Footnote 95

Mechanisms, Part II: Early Nineteenth-Century Prussia—The Black Death and Footprints of Serfdom

In addition to the pre-1500 analysis focused on changes in political institutions, we assess whether the proposed mechanisms are consistent with differences in socioeconomic structures across German-speaking Central Europe. According to our theoretical framework, serfdom as a socioeconomic institution should have waned in areas severely affected by the Black Death whereas it should have grown in areas largely spared by the outbreak. We provide qualitative evidence in favor of this proposition in the supplementary material.Footnote 96 To complement our discussion of the link between the Black Death and changes in labor coercion, we also empirically evaluate the degree to which variation in mortality is associated with two footprints of serfdom seen in early nineteenth-century Prussia: the dominance of large estates in agriculture and the prevalence of agricultural servants. The underlying measures were originally compiled by the Prussian state as part of the first available standardized and comparable data set of socioeconomic characteristics across large parts of German-speaking Europe.

Specifically, we analyze the spatial association between Black Death intensity and the following two outcome variables:

—1. Large estates as a proportion of all agricultural properties 1816: Data on the number of different types of farms are provided by Sascha Becker and colleagues.Footnote 97 We compute the proportion of farms in the largest category recorded by the Prussian census, which is “over 300 Prussian morgen” (approximately 189 acres). The coercive imposition of onerous labor obligations in the German-speaking lands went hand-in-hand with the consolidation of large, export-oriented estates.Footnote 98 Thus, we expect Black Death intensity to be negatively associated with this measure.

—2. Agricultural servants as a proportion of the overall population 1816/1819: These data provide a direct measure of the legacy of serfdom. Although agricultural servants and serfs are not one and the same (since serfdom was formally abolished in Prussia in 1807), in practice most freed serfs continued to work their lords’ lands as renters and wage laborers. Thus, the number of agricultural servants represents a good proxy for the former population of serfs. Due to limitations on available data, the number of servants is from the year 1819 and the population numbers are from 1816. As above, we expect Black Death intensity to be negatively associated with this measure.

We use the same set of control variables as in our main analysis. Geographic data on the location of Prussian counties were provided by the ifo Institute for Economic Research (ifo Zentrum für Bildungsökonomik).Footnote 99

Empirical Specifications

We use a range of outcome variables with different properties and adjust our models accordingly. With respect to land inequality and Conservative Party vote share, we primarily use ols regression with clustered standard errors.Footnote 100 We also use ols regression when analyzing a number of variables in our extensions and mechanism sections.Footnote 101 For all truncated outcome variables, in the supplementary material we discuss an alternative set of results using Tobit models.

The format of our ols regressions is as follows:

where yi is the respective outcome and xi represents a vector of covariates at the electoral district level (i).Footnote 102 ß 1 represents the coefficient of the bdei score.

We depart from ols when it is called for, based on the properties of our outcome variables. When considering net electoral disputes, which is a count variable, we use quasi-Poisson models. And we use logistic regression when analyzing the binary variable introduction of participative elections 1300–1500.

The bdei score is computed in the following way:

where LMRj ∈ (0,1] is the local mortality rate at outbreak site j, and DISTij ∈ [0,1] is the distance between i and j, which is used as the weight (with locations farther away from i being weighted down). The parameter k ∈ {3, 6, 9, 12, 15} for versions 1 through 5 of the BDEI score, respectively, represents the distance discount factor. We compute different versions of the BDEI score to show that results are not dependent on any single value of k. The farther an outbreak site is from the location under consideration i, the more it is exponentially discounted. To make the different versions of the raw bdei score more comparable and our results easier to interpret, we standardize them to have a mean of μ = 0 and a standard deviation of σ = 1.

VI. Results

Imperial Germany: Socioeconomic Conditions and Political Outcomes

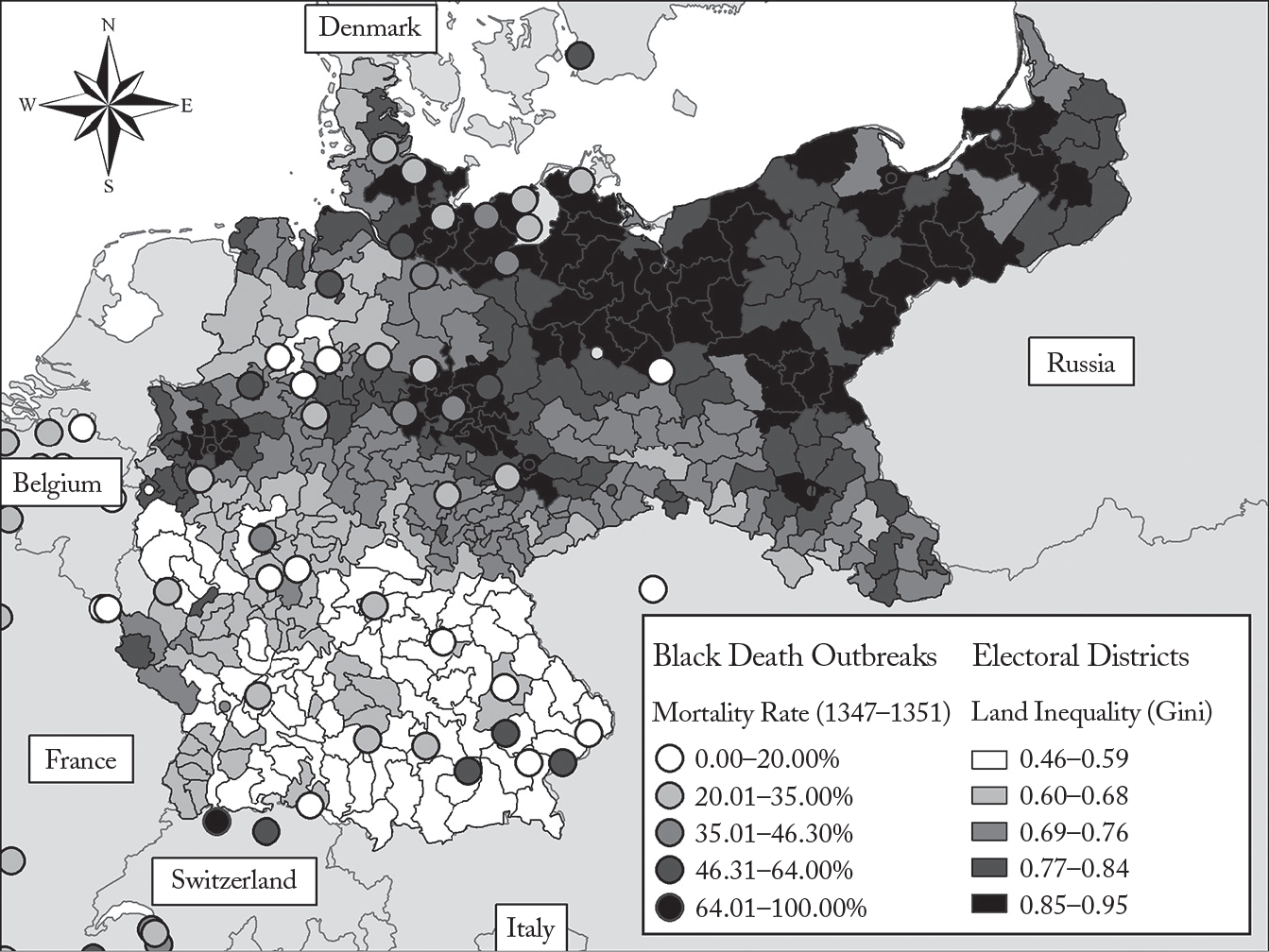

The results of our empirical analysis reveal a strong relationship between the historical intensity of the Black Death and long-term political and socioeconomic outcomes in Imperial Germany. We begin by considering a graphic overview of landholding inequality across Germany’s electoral districts, as shown in Figure 3.Footnote 103 Levels of landholding inequality in a district are indicated by that district’s shade of gray. Additionally, towns with recorded outbreaks are displayed as circles, and the intensity of the outbreaks is also shown by each circle’s shade of gray. The northeastern districts exhibit especially high levels of landholding inequality. And almost all electoral districts in the easternmost parts, where the plague was least severe, have relatively high levels of landholding inequality.

Figure 3. Landholding Inequality by Electoral District

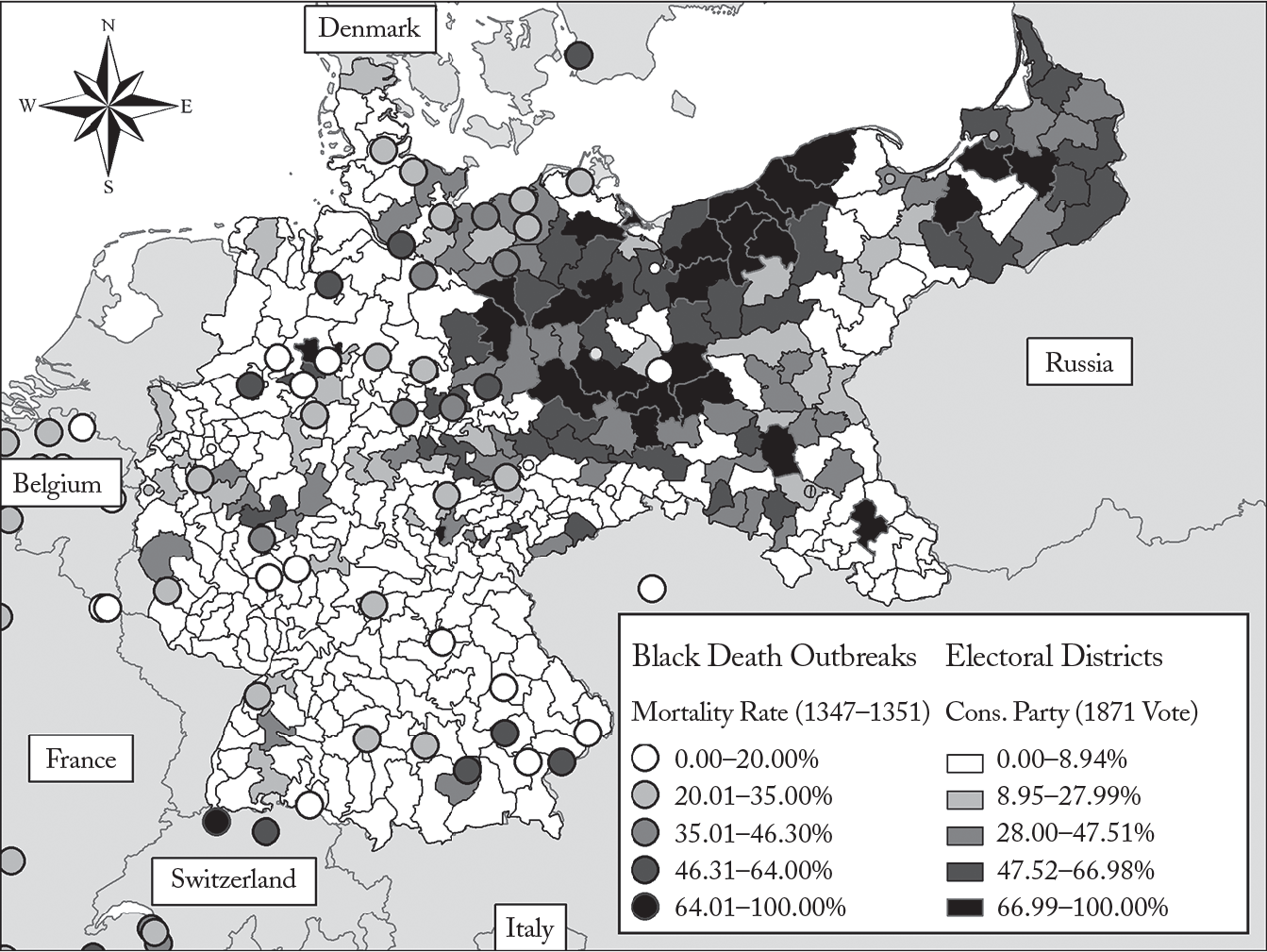

As discussed, we also expect a long-term impact of variation in Black Death intensity on Conservative Party vote share, with high vote shares indicating the political-economic equilibrium linked to low historical Black Death intensities. This is clearly reflected in Figure 4. The party’s vote share is consistently higher in areas with fewer and less intense recorded outbreaks. Similarly, as shown in Figure 5, the total number of electoral disputes between 1871 and 1912 is also higher in the northeast than in many parts of the west and south.

Figure 4. Conservative Party Vote Share by Electoral District (1871)

Figure 5. Net Electoral Disputes by Electoral District (1871–1902)

Next, we turn to our regression analysis. Table 1 shows our findings with respect to landholding inequality. In addition to a first set of models (1–5) that are based on our key independent variable only, we provide a second set (6–10) that include the previously discussed controls. Across all specifications, the bdei score has a significant negative impact on landholding inequality, indicating the persistent influence of the Black Death. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in the bdei score results in a decrease in the value of landholding inequality (Gini) that ranges from 0.042 to 0.061 (0.350 to 0.508 standard deviations). Figure 6 shows the predicted values for different magnitudes of bdei score v1.

Table 1. Landholding Inequality (Gini Coefficient) (OLS) a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; clustered standard errors

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1-v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: electoral district of Imperial Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

Figure 6. Predicted Values Plot: BDEI Score v1 and Landholding Inequality (Gini)

Table 2 shows the results with respect to Conservative Party vote share. As with our previous analyses, we also provide models without (1–5) and with (6–10) control variables. In line with our theory, the Conservative Party is weaker in areas that had more severe outbreaks, indicated by a high bdei score. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in the bdei score leads to a reduction in the party’s vote share ranging from 0.106 (10.6 percentage points) to 0.141 (14.1 percentage points) (0.426 to 0.566 standard deviations). The results again highlight the pandemic’s long-term influence. Figure 7 shows the predicted values for different magnitudes of the bdei score v1.

Table 2. Conservative Party Vote Share (OLS) a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; clustered standard errors

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1-v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: electoral district of Imperial Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

Figure 7. Predicted Values Plot: BDEI Score v1 and Conservative Party Vote Share 1871

Table 3 shows the results of quasi-Poisson regressions on electoral disputes. Here, we also confirm our theoretical expectations: places with more intense outbreaks have significantly fewer electoral disputes. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in the bdei score leads to a change in the logs of expected counts ranging from –0.172 to –0.313.

Table 3. Net Electoral Disputes (Quasi-Poisson) a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; quasi-Poisson; clustered standard errors

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1—v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: electoral district of Imperial Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

In sum, we find comprehensive evidence that the Black Death shaped socioeconomic structures and political behavior in the long run. In terms of both landholding inequality and the Conservative Party’s electoral viability, we find that regional variation in plague outbreaks in the fourteenth century has strong predictive power for a number of outcomes in the nineteenth century. These results indicate that this biological shock fundamentally reshaped society in areas where it hit hardest while reinforcing socioeconomic and political hierarchies in other regions, leading to distinct political-economic equilibria that persisted for generations.

Imperial Germany: Extensions of the Empirical Analysis

We present multiple extensions in the supplementary material.Footnote 104 In the first extension, we add covariates for population size and Prussia. In the second extension, we consider a variable that reflects variation in the Reformation’s long-term impact: a district’s share of Catholics. In the third extension, we calculate the bDEI score based on an alternative set of outbreak observations. In the fourth extension, we condition our analysis of landholding inequality on the relevance of agriculture in the district.Footnote 105 In the fifth extension, we use the timing of outbreaks in a two-stage least squares setup to isolate exogeneous variation in mortality rates.Footnote 106 In the sixth extension, we replace our distance measures to geographic features with dummy variables. In the seventh extension, we control for variability in agricultural (caloric) potential to account for historical information asymmetries.Footnote 107 In the eighth extension, we include quasi-random spatial fixed effects to address suggestions made by Thomas Pepinsky, Sara Wallace Goodman, and Conrad Ziller.Footnote 108 In the ninth extension, we use two alternative data sets to compute the bdei score.Footnote 109 In the tenth extension, we use data by Christos Nüssli and Marc-Antoine Nüssli to introduce fixed effects based on pretreatment administrative borders.Footnote 110 In the eleventh extension, we consider three alternative outcome measures: (1) the combined vote share of all conservative parties in 1871, (2) the combined vote share of all major liberal and moderate parties in 1871, and (3) the Conservative Party’s vote share in 1874. In the twelfth extension, we account for city population sizes when computing the bdei score. In the thirteenth extension, we manually limit the regions used to construct the bdei score to neighboring ones. And in the fourteenth and last extension, we account for pre-1500 caloric potential.Footnote 111 All told, our key results are robust across a large set of alternative approaches to measurement and statistical analysis.

Weimar Germany: Persistence of Local Political Cultures and Votes for the National Socialist Party

Besides the extensions discussed above, the substantively most important addition to our empirical test is an analysis of Weimar Germany’s 1930 and July 1932 elections. As shown in figures 8 and 9, the electoral strength of the NSDAP in both elections is highly correlated with the Black Death’s historical intensity as measured by bdei score v1.

Figure 8. Predicted Values Plot: BDEI Score v1 and NSDAP Vote Share 1930

Figure 9. Predicted Values Plot: BDEI Score v1 and NSDAP Vote Share July 1932

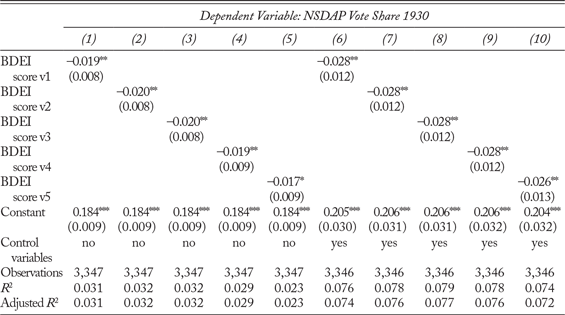

Tables 4 and 5 provide further details with respect to these results, underscoring the persistent negative association between historical Black Death exposure intensity and the vote share of antidemocratic parties. In the 1930 election, a one standard deviation increase in the bdei score leads to a reduction in the expected vote share of the NSDAP ranging from 0.017 (1.7 percentage points) to 0.028 (2.8 percentage points) (0.160 to 0.264 standard deviations). In the election of July 1932, a one standard deviation increase in the bdei score leads to a reduction in the expected vote share of the NSDAP ranging from 0.034 (3.4 percentage points) to 0.088 (8.8 percentage points) (0.233 to 0.603 standard deviations). These results indicate that aspects of the spatial divergence in political cultures created by the Black Death persisted into the Weimar Republic despite the socioeconomic and geographic dislocations ushered in by industrialization and WWI.Footnote 112

Table 4. NSDAP Vote Share 1930 (OLS) a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; clustered standard errors

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1—v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: town/city in Weimar Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

Table 5. NSDAP Vote Share July 1932 (OLS) a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; clustered standard errors

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1—v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: county in Weimar Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

Mechanisms, Part I: Pre-Reformation Germany—Introduction of Participative Elections

Next, we focus on the underlying mechanisms by which we postulate that the Black Death exerted a long-term effect on political outcomes in Germany. We begin with a set of analyses that examine pre-Reformation Germany. We study outcomes prior to the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517, to rule out the possibility that the Reformation could be responsible for the observed outcomes. By showing that the Black Death is associated with key changes in proto-democratic institutions by the year 1500 (when compared to 1300), we demonstrate that some of the mechanisms discussed can be observed many years before the Reformation affected Germany’s political landscape.

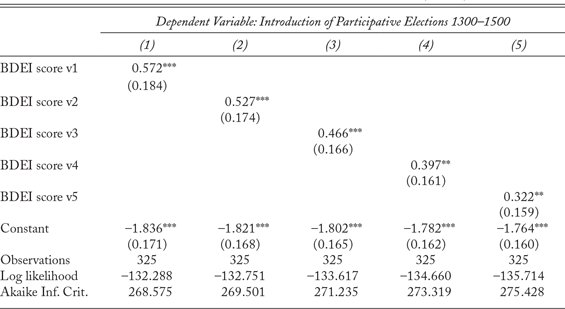

Table 6 shows the results for introduction of participative elections 1300–1500 for 325 towns. The results indicate that towns more strongly exposed to the Black Death were significantly more likely to adopt participative institutions by 1500.

Table 6. Introduction of Participative Elections 1300–1500 (Logit)a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1-v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: town in pre-Reformation Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

In Table 7, we add a variety of control variables, including geographic factors. While the results are at or below the threshold of statistical significance in two specifications, the direction of the effect remains the same. Indeed, the lower level of significance is likely due to the much smaller number of cases for which covariate data are available. Overall, the evidence suggests that demographic collapse from the Black Death set in motion institutional changes that are consistent with patterns of political behavior observed in the nineteenth century.

Table 7. Introduction of Participative Elections 1300–1500 (with Controls) (Logit)a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1-v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: town in pre-Reformation Germany) was exposed to the pandemic.

Mechanisms, Part II: Early Nineteenth-Century Prussia—The Black Death and Footprints of Serfdom

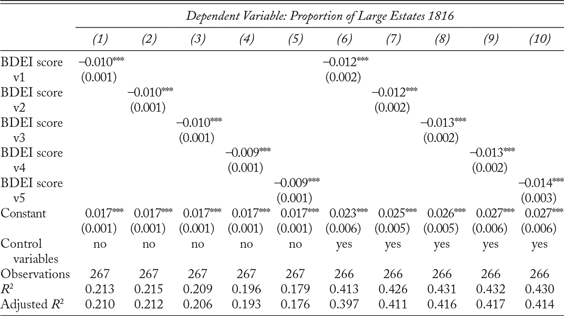

In the final set of analyses, we consider socioeconomic outcomes in early nineteenth-century Prussia. These analyses evaluate whether geographical variation in Black Death intensity is associated with proxy measures of the strength of serfdom long before 1871.

Our results indicate that both proportion of large estates 1816 and proportion of agricultural servants 1816/1819 are associated with the Black Death’s historical intensity. Specifically, Table 8 shows a persistent negative relationship between the BDEi score and the proportion of large estates, indicating that the areas hit hardest by the Black Death had the smallest relative number of large estates in 1816. Table 9 shows a similar pattern when it comes to agricultural servants as a proportion of the overall population. In accordance with our mechanisms, the results indicate that areas hit hardest by the Black Death had a significantly smaller number of agricultural servants, indicating an economy that was less hierarchical and less agriculturally centered.

Table 8. Proportion of Large Estates 1816 (OLS)a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1—v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: geographic area in early nineteenth-century Prussia) was exposed to the pandemic.

Table 9. Proportion of Agricultural Servants (of Total Population) 1816/1819 (OLS)a

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

a The BDEI score shows how strongly a unit of analysis was exposed to the Black Death (1347–1351). The different versions of this score (v1—v5) vary in the discount factor (3, 6, 9, 12, 15). A higher discount factor implies that historical Black Death outbreaks at a greater distance receive a smaller weight in calculating our measure of how strongly the unit of analysis (here: geographic area in early nineteenth-century Prussia) was exposed to the pandemic.

VII. Conclusion

Contemporary social science emphasizes the importance of actions taken during critical junctures to explain differences in the nature, scope, and quality of government across societies.Footnote 113 As moments in time, critical junctures are defined by significant upheaval and fluidity:Footnote 114 institutional structures and social arrangements long taken for granted are suddenly amenable to changes that would have been inconceivable under normal circumstances. Such windows for change do not open easily. The antecedent to a critical juncture may be a shock that profoundly reorders economic circumstances or the de facto balance of power in a society.Footnote 115 Compared to the various types of shocks that may produce such an alteration in circumstances, the demographic collapse caused by a pandemic certainly numbers among the most consequential.

Our study examines the long-term legacy of one of the most profound demographic shocks in European history: the loss of life due to the Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century. Concentrating on the historical experience of the German-speaking areas of Europe from the arrival of the Black Death until the onset of the German Empire in 1871 and beyond, the study explicitly lays out all four stages of analysis needed to establish the importance of a critical juncture:Footnote 116 (1) characterization of the shock (the intensity of exposure to the Black Death); (2) the critical juncture itself (the decision to roll back or augment labor coercion); (3) the mechanisms of production of the legacy (changes in economic arrangements and political institutions resulting from changes in labor coercion); and (4) the legacy (electoral behavior in the late nineteenth century and in the Weimar period).

Empirically, our article shows that areas more intensely affected by the Black Death developed more inclusive political institutions at the local level and more equitable ownership of land, both reflecting a fundamentally changed political-economic equilibrium. Contrariwise, those areas less affected by the Black Death maintained political institutions and land ownership patterns that concentrated political and economic power in a small elite. In the first set of areas, voters in the late nineteenth century would come to reject the Conservative Party at the ballot box, an outcome indicative of voters’ autonomy from the directives of the landed nobility. In the second set of areas, voters overwhelmingly cast their ballots in favor of the Conservative Party, indicative not only of an antidemocratic political culture, but also of the ability of the landed elite to guide decisions at the ballot box. By restructuring political institutions and social organization at the local level, the Black Death had significant consequences for how citizens would come to engage in mass politics.

Importantly, the remarkable spatial divergence in political cultures created by the Black Death launched a political conflict between conservative and progressive forces that persisted well into the Weimar Republic. That conflict is evident in the clear association between historical Black Death exposure and votes for the National Socialist Party. The nsdap’s extremely antidemocratic and illiberal political views found fertile ground in the parts of Germany that had limited historical experience with democratic participation at the local level. Thus, the Black Death did not just shape institutional development in Central Europe during the early modern period and electoral outcomes during the nineteenth century. Its echoes may still be found in the party politics of the Weimar Republic’s doomed experiment with mass democracy—an era of instability that led to the darkest episode in German history.

The experience of the German-speaking lands in the wake of the Black Death makes it clear that abrupt and dramatic shifts in relative factor prices may have significant consequences for long-term institutional development. Of course, pandemics are not alone in their ability to shift prices in this way: major wars can produce similar effects, as can large-scale migration and periods of revolutionary technological change. But pandemics are especially significant for social scientists because they offer distinctive opportunities for inference. Since pandemics are not products of human choice (like war and large-scale migration, for example), they may—in certain circumstances—unsettle relative factor prices in a manner more akin to that of a random shock. Thus, while pandemics are not necessarily uniquely influential for institutional development, they can be especially revealing when it comes to the way institutional development responds to changes in the relative power of labor versus capital and land.

What specific lessons does the Black Death offer about the potentially transformative role of a pandemic? One important lesson is that the depth of the shock matters. As the Black Death made its way through Europe, it imposed incalculable physical and emotional suffering and profoundly darkened the tenor of literature, music, and the visual arts. But despite the death and suffering, the world inherited by survivors and their descendants in areas ravaged by the Black Death was in many ways preferable to the world in which their ancestors had long toiled. Massive demographic collapse improved the bargaining power of labor, leading to major changes in social organization and political institutions. These developments would upgrade living standards and provide opportunities for meaningful political engagement. In a dark twist of irony, the experience of the Black Death demonstrates that the long-term political independence of labor may have blossomed from the graves of workers.

As a general matter, however, one should not expect all pandemics to have these types of consequences. To radically restructure labor relations—the catalyst for the social and political changes wrought by the Black Death—a disease shock must be very large, must affect individuals in their prime working age, and cannot be easily reversible. Pandemics that infect great numbers of individuals but have relatively low mortality rates, such as the Spanish Flu of 1918 and the global Covid-19 outbreak that started in 2019–2020, do not change the labor supply to the extent needed to fundamentally alter factor prices. The same is true for pandemics that have a high mortality rate but limited contagiousness, as was the case for hiv/aids before the widespread use of antiretroviral drugs. Diseases that primarily afflict children, such as measles and polio, also do not reconfigure relative factor prices—at least not in the long run—as reproductive strategies may compensate for heightened child mortality.Footnote 117

To produce a labor market shock that generates dynamics like those initiated by the Black Death, a pandemic would have to combine high contagiousness with high mortality for working-age adults. The Ebola virus seemed to have this potential, but the recent development of a vaccine has reduced Ebola’s threat to human life. Although no obvious alternative threat lies on the horizon, the present combination of high population density and unprecedented global interconnectedness will surely make the next great pandemic all the more destructive when it does arise. In the end, the Black Death offers this important reminder: when the next wave of destruction emerges, contemporary labor-repressive institutions may well be washed away in its wake.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887121000034.

Data

Replication data for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/M0PKZE.

Acknowledgments

Both authors contributed equally to this article. Helpful comments were provided by Lasse Aaskoven, Manuela Achilles, John Aldrich, Shan Aman-Rana, Margaret Anderson, Kyle Beardsley, Pablo Beramendi, Carles Boix, William Brustein, Ernesto Calvo, Pawel Charasz, Volha Charnysh, Ali Cirone, Kerem Coşar, Paul Freedman, Adriane Fresh, Jeff Frieden, Olga Gasparyan, Michael Gillespie, Robert Gulotty, Connor Huff, Noel Johnson, Stefano Jud, Justin Kirkland, Herbert Kitschelt, Mark Koyama, Markus Kreuzer, Eroll Kuhn, Erin Lambert, Michael Lindner, David Luebke, Eddy Malesky, Lucy Martin, Mat McCubbins, Christian McMillen, Ralf Meisenzahl, Victor Menaldo, Carl Müller-Crepon, Rachel Myrick, Nicola Nones, Sheilagh Ogilvie, John O’Loughlin, Sonal Pandya, Vicky Paniagua, Joan Ricart-Huguet, Ron Rogowski, Jim Savage, Walter Scheidel, Hanna Schwank, Emily Sellars, Renard Sexton, Jonathan Sperber, David Stasavage, Tilko Swalve, Georg Vanberg, Emily VanMeter, Nico Voigtländer, Fabian Wahl, David Waldner, Peter White, Erik Wibbels, and several anonymous reviewers. We also thank Jonathan Sperber for data on electoral outcomes in Imperial Germany; Mark Koyama, Boris Schmid, Ulf Büntgen, and Christian Ginzler for data on recorded outbreaks of the Black Death; Sascha Becker, Erik Hornung, and the ifo Institute for Economic Research for additional information on the ifo Prussian Economic History Database (iPEHD); Barbara Peck for careful editing of the article; and Sean Morris for his excellent research assistance. The development of our study profited significantly from virtual seminars at Duke University, the University of Virginia, the University of Konstanz, the University of Washington, the University of California at Los Angeles, the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, the Global Research in International Political Economy (GRIPE) Webinar, the Virtual Workshop in Historical Political Economy (VWHPE), the Southern Workshop in Empirical Political Science (SoWEPS), and the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge generous funding from the Corruption Laboratory for Ethics, Accountability, and the Rule of Law (CLEAR Lab), which is part of the Democracy Initiative at the University of Virginia.

Authors

Daniel W. Gingerich is an associate professor of politics at the University of Virginia and director of UVA’s Quantitative Collaborative. He also codirects the Corruption Laboratory for Ethics, Accountability, and the Rule of Law (CLEAR Lab). His research examines the factors that inhibit or enhance the quality of democracy around the world, with an emphasis on democratic institutional design, informal institutions, and historical processes. He can be reached at [email protected].

Jan P. Vogler is a postdoctoral research associate in the political economy of good government in the CLEAR Lab and the Department of Politics at the University of Virginia. In fall 2021, he will be an assistant professor in quantitative social science in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Konstanz. His research interests include the organization of public bureaucracies, political and economic competition (in domestic and international settings), legacies of historical events, structures and perceptions of the European Union, and the determinants of democracy and authoritarianism. He can be reached at [email protected].