The occurrence of weed populations with resistance to herbicides encompassing multiple sites of action is increasingly common. There are now more than 50 weed species for which populations have been reported resistant to herbicides encompassing two sites of action and, in the worst-case scenario reported thus far, a single population is resistant to herbicides encompassing seven sites of action (Heap Reference Heap2016). Resistance in a single plant (or population) to multiple herbicides can be due to cross resistance or multiple resistance. In the case of cross resistance, a single mechanism confers resistance to multiple herbicides, whereas for multiple resistance, a plant has more than one resistance mechanism (Vencill et al. Reference Vencill, Nichols, Webster, Soteres, Mallory-Smith, Burgos, Johnson and McClelland2012). Multiple resistance is particularly problematic in outcrossed weeds such as waterhemp: pollen movement within and among populations effectively “stacks” different resistance traits.

The first multiply resistant waterhemp population was reported by Foes et al. (Reference Foes, Liu, Tranel, Wax and Stoller1998). This population contained resistances to both photosystem II (PSII) inhibitors and acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitors due to target-site mutations in the corresponding genes. Subsequently, waterhemp populations with resistances to herbicides encompassing three, four, and then five sites of action were reported (Heap Reference Heap2016). Many such populations likely have a corresponding number of resistance mechanisms (e.g., Bell et al. Reference Bell, Hager and Tranel2013; Legleiter and Bradley Reference Legleiter and Bradley2008; Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Chatham, Riggins, Tranel and Bradley2015) and therefore exhibit true multiple resistance. Metabolic-based resistance to herbicides has been reported in waterhemp, however, suggesting that resistance to multiple herbicides in some cases could be due in part to cross resistance (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Riggins, Hasuman, Hager, Riechers, Davis and Tranel2015; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Kaundun, Tranel, Riggins, McGinness, Hager, Hawkes, McIndoe and Riechers2013).

If resistances to two herbicides are due to cross resistance, then the two herbicide resistance traits will cosegregate. Stated differently, because the two herbicide resistances are conferred by the same mechanism, they are really a single genetic trait. Alternatively, if resistances to two herbicides are due to multiple resistance, then the traits are genetically distinct and not expected to cosegregate. Instead, the traits should follow Mendel’s law of independent assortment (Gardner and Snustad Reference Gardner and Snustad1984). Of course, independent assortment does not occur if the genes controlling the traits are physically linked, i.e., nearby on the same chromosome. The chance of any two genes being physically linked is relatively small, however. For example, in the case of waterhemp, which has a haploid chromosome number of 16 (Rayburn et al. Reference Rayburn, McCloskey, Tatum, Bollero, Jeschke and Tranel2005), the odds of two genes being on the same chromosome are 0.0625 (assuming all chromosomes have the same number of genes), and much less than that for being in close proximity on the same chromosome.

Our group previously reported a waterhemp population (Adams County resistant, ACR) with resistances to atrazine, ALS inhibitors, and protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) inhibitors (Patzoldt et al. Reference Patzoldt, Tranel and Hager2005). The resistance to atrazine is likely due to enhanced metabolism (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Kaundun, Tranel, Riggins, McGinness, Hager, Hawkes, McIndoe and Riechers2013), whereas resistances to the ALS and PPO inhibitors are due to target-site changes: Trp574Leu substitution and Gly210 deletion (ΔG210), respectively (Patzoldt et al. Reference Patzoldt, Hager, McCormick and Tranel2006; Patzoldt and Tranel 2007). Despite the resistances to ALS and PPO inhibitors being attributed to distinct genes (ALS and PPX2), anecdotal observations suggested that these two resistances did not follow independent assortment. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether ALS and PPX2 are linked in waterhemp.

Materials and Methods

Herbicide-based Segregation Analysis

Backcross lines were evaluated for cosegregation of resistances to ALS and PPO inhibitors. These lines were previously generated and described by Patzoldt et al. (Reference Patzoldt, Hager, McCormick and Tranel2006). Briefly, crosses were made between ACR and a herbicide-sensitive population, and resulting progeny were backcrossed to plants from the sensitive population. Because the sensitive parent was the recurrent parent, the backcross lines are designated BCS. Prior to use, seeds were removed from cold storage (4 C) and stratified as described by Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Hager and Tranel2013) to improve germination. Three BCS lines that exhibited high germination rates were selected for analysis.

Replicate 100-seed samples of each BCS line were sown on growing medium in 56 cm by 28 cm, 6.5-cm-deep flats with eight equal partitions (100 seeds per partition). The growing medium was a 3:1:1:1 mix of commercial potting mix (Sunshine Mix #1/LC1, Sun Gro Horticulture, 770 Silver Street, Agawam, MA 01001):soil:peat:torpedo sand. Flats were subirrigated overnight prior to sowing to moisten the growth medium. At least three 100 seed replicates were planted per BCS line, depending on germination frequencies of the lines observed in preliminary experiments. After the seeds were covered with approximately 2 mm of the same growth medium, imazethapyr (Pursuit, 240 g ai L−1, BASF, 26 Davis Drive, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709) was applied to the flats. A high rate of imazethapyr (1750 g ha−1) was used due to high organic matter content of the soil and because the ALS Trp574Leu substitution confers a very high level of resistance that is functionally dominant even at this dosage. Approximately 1 mm of simulated rainfall was sprayed over the flats to incorporate the herbicide. At 10 d after treatment (DAT), seedlings surviving the imazethapyr PRE application were transplanted individually into containers (Ray Leach SC10 “Cone-tainer,” Stuewe & Sons, 31933 Rolland Drive, Tangent, OR 97389) containing the same growth medium as described above. Three days after transplanting, seedlings were treated with lactofen (Cobra, 240 g ai L−1, Valent USA, 1600 Riviera Avenue, Walnut Creek, CA 94596). A relatively low rate of lactofen (6.6 g ha−1) was used: in preliminary experiments this rate controlled the sensitive population but not plants heterozygous for the resistance allele (F1 plants). At the same time that imazethapyr preselected seedlings were treated with lactofen, 49 seedlings of the same age but not preselected by imazethapyr were also treated with lactofen. The number of lactofen-resistant plants (i.e., survivors) was counted 14 DAT.

Plants were cultured in a greenhouse maintained at 28/22 C day/night with a 16:8 h photoperiod. Natural sunlight was supplemented with mercury halide lamps to provide a minimum of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 at the plant canopy. Herbicide applications were made using a compressed-air research sprayer (DeVries Manufacturing, 86956 State Highway 251 Hollandale, MN 56045) fitted with a Teejet 80015 EVS nozzle (Teejet Technologies, P.O. Box 7900, Wheaton, IL 60187) calibrated to deliver 185 L ha−1 at 275 kPa. The nozzle was maintained approximately 45 cm above the plant canopy. Three independent backcross lines were evaluated in each of two runs separated in time. Responses between runs were similar, so data were pooled. The exact test of goodness of fit (McDonald Reference McDonald2014) was used to determine whether results deviated from expectations for single dominant genes showing independent assortment.

Molecular Marker Confirmation

To confirm results of the herbicide-based segregation analysis, 23 plants from each of the same three BCS lines were evaluated for the presence of the herbicide-resistance ALS and PPX2 alleles. Seeds were germinated and seedlings grown as described above but with no herbicide selection. DNA was extracted from the seedlings and subjected to polymerase chain reaction–based assays for the resistance alleles as described previously (Foes et al. Reference Foes, Liu, Vigue, Stoller, Wax and Tanel1999; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hager and Tranel2008). The molecular marker data for two or three plants from each line were ambiguous; these plants were therefore discarded from the analysis.

Genomic DNA Sequence Evidence for Linkage

Although an assembled genome for waterhemp is not available, a draft assembly is available for the closely related species, grain amaranth (Clouse et al. Reference Clouse, Adhikary, Page, Ramaraj, Deyholos, Udall, Fairbanks, Jellen and Maughan2016). Both ALS and PPX2 gene sequences from grain amaranth (obtained previously by Maughan et al. [Reference Maughan, Sisneros, Luo, Kudrna, Ammiraju and Wing2008]) were used in BLAST searches of the grain amaranth contigs available at CoGe (id 40120, https://genomevolution.org/coge).

Results and Discussion

Because both of the resistance traits are dominant (under the conditions at which the herbicides were used), 50% of the BCS plants were expected to be resistant each to ALS and PPO inhibitors. The frequency of resistance to ALS inhibitors in the BCS lines was not determined in the herbicide-based segregation analysis, because the ALS inhibitor was applied PRE and the lines exhibited variable germination rates. Segregation of the ALS resistance allele was as expected, however, based on molecular analysis (see below). In regard to resistance to PPO inhibitors, segregation did not deviate (P<0.05) from the expected 1:1 segregation. Specifically, 45 to 60% of plants not previously selected by imazethapyr were resistant to lactofen (Table 1).

Table 1 Segregation of resistance to a protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO)-inhibiting herbicide (lactofen) in backcross lines (BCS; sensitive population as recurrent parent) with and without preselection by an acetolactate synthase (ALS)-inhibiting herbicide (imazethapyr).

a Expected numbers are based on the allele for resistance to PPO-inhibiting herbicides being dominant and assorting independently from resistance to imazethapyr.

b Probability that the observed number of lactofen-resistant plants was different from the expected number based on the exact test of goodness of fit.

If resistances to ALS and PPO inhibitors independently assort, then prior selection by imazethapyr should not influence the frequency of resistance to lactofen. In contrast to this expectation, however, 91 to 94% of the imazethapyr-resistant plants were also resistant to lactofen (Table 1). The highly significant deviation from the expected 50% lactofen resistance indicated strong (although not complete) linkage of the two resistance traits.

Molecular marker analysis of inheritance of the ALS and PPX2 alleles confirmed the expected segregation (1:1) of the resistance and sensitivity alleles for each of the two genes (Table 2). Although sample sizes were small, none of the individual BCS lines deviated (P<0.05) from 1:1 expected ratios for the individual genes and, summed across all three lines, presence:absence of resistance alleles was 32:30 and 29:33 for ALS and PPX2, respectively. Additionally, molecular analysis confirmed the cosegregation that was observed from the herbicide-based evaluation. Specifically, for each BCS line, recombination of the parental alleles was observed in only 5% of the plants.

Table 2 Segregation of ALS and PPX2 resistance alleles in backcross lines (BCS; sensitive population as recurrent parent).Footnote a

a Data were obtained from a total of 20 (BCS-2) or 21 plants; expected numbers are based on 20 plants. Each BCS line deviated (p<0.001) from the results expected for independent assortment of the two genes.

The genetic distance of two genes can be expressed in centimorgans, where 1 cM equals 1% recombination. When phenotypic and genotypic data across all BCS plants analyzed (46 recombinants out of 610 plants) were pooled, the Trp574 codon of ALS was calculated to be 7.5 cM from the Gly210 codon in PPX2. Using this recombination frequency, the logarithm of odds (LOD) score was calculated to be 113. An LOD score of 3 is considered significant enough to indicate linkage (Ott Reference Ott1999). The very high LOD score we obtained is due to both the low recombination frequency observed and the large number of plants analyzed.

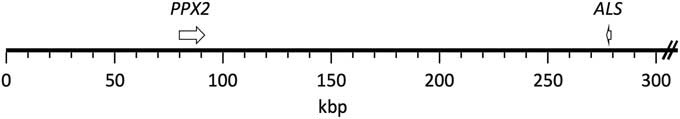

The published grain amaranth genome (Clouse et al. Reference Clouse, Adhikary, Page, Ramaraj, Deyholos, Udall, Fairbanks, Jellen and Maughan2016) contained complete sequence coverage of both ALS and PPX2 genes. These two genes were found to be present on the same scaffold, scaffold 30, which is about 1.3 Mb in length (Figure 1). PPX2 and ALS are oriented in opposite directions, and the distance between the Trp574 ALS codon and the Gly210 PPX2 codon was found to be 195,437 bp. Physical linkage of ALS and PPX2 genes in a few other plants for which whole genomes have been published was investigated but generally was not found to occur (unpublished data).

Figure 1 Mapping of PPX2 and ALS genes to the grain amaranth genome. Both genes were found in scaffold 30 (1,306,592 bp; only the first 300 kb are depicted). The genes are depicted from start codon to stop codon. The resistance-conferring mutations (ΔGly210 and Trp574Leu) correspond to positions 82,022 and 277,460, respectively, of the scaffold.

The physical linkage of ALS and PPX2 genes in the closely related grain amaranth provides an explanation for the observed genetic linkage of the two genes in waterhemp. Assuming an identical physical distance between the two genes in waterhemp, the observed recombination frequency equates 1cM to about 26 kb (7.5 cM between 195,437 bp). Although this recombination frequency is about 10-fold higher than the genome-wide recombination rate in Arabidopsis [Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.], recombination rates are known to vary among species and also vary widely depending on chromosome location (Singer et al. Reference Singer, Fan, Chang, Zhu, Hazen and Briggs2006). Furthermore, the actual distance between the two genes in waterhemp could be more or less than that in grain amaranth. Because an assembled genome is not available for waterhemp, the overall level of conservation between its genome and that of grain amaranth is unknown. A portion (4,797 bp) of the waterhemp PPX2 gene is available (GenBank accession DQ394875.1). This portion contains the first nine exons and comprises 43% of the coding sequence. Alignment of this to the corresponding region of the grain amaranth PPX2 gene shows 75% identity (unpublished data). Much of the lack in sequence identity is due to different lengths of intron sequences (at the amino acid level, the complete proteins have 97% identity). Thus, although there is high DNA conservation between grain amaranth and waterhemp, there is also enough dissimilarity that the distances between ALS and PPX2 could be substantially different in the two species. Once the actual distance between ALS and PPX2 in waterhemp is obtained, one can reevaluate our very preliminary finding of a potentially high rate of recombination between the two genes in waterhemp. Interestingly, Thinglum et al. (Reference Thinglum, Riggins, Davis, Bradley, Al-Khatib and Tranel2011) previously suggested that there might be a high rate of recombination within the waterhemp PPX2 locus.

Regardless of the potential recombination frequency, results reported herein provide direct genetic and indirect physical evidence for linkage of ALS and PPX2 genes in waterhemp. The chances of two distinct target site–based herbicide-resistance genes being so closely linked are low, especially in a species that has 16 haploid chromosomes. From a practical standpoint, linkage of the resistance genes might have minimal impact on the population genetics and dynamics of their resistance evolution. Despite the linkage, recombination—even at only 7.5%—is sufficient to likely negate any evolutionary significance, especially for an outcrossed species that produces thousands of offspring every generation. Mathematical modeling could help reveal the significance of such linkage in herbicide-resistance evolution, and it would be interesting to apply such modeling to species with contrasting reproductive biology. Regardless, our documentation of linkage serves as an important reminder that independent assortment should not be assumed when studying herbicide-resistance genes.

What may be of most practical significance is the impact that linkage could have in terms of elucidating herbicide-resistance genes. Cosegregation analysis is often used to support the involvement of a candidate resistance gene with a resistance trait. For example, cosegregation analysis initially implicated PPX2 with resistance to PPO inhibitors in waterhemp (Patzoldt et al. Reference Patzoldt, Hager, McCormick and Tranel2006). Similar analysis using a marker for ALS could have led to the erroneous conclusion that ALS was responsible for the resistance. Granted, the function of ALS is known, and one would therefore be unlikely to go down such an erroneous path. Consider, however, cosegregation analysis of nontarget-site herbicide-resistance genes. There are often multiple candidates for such genes (e.g., Arabidopsis has nearly 250 P450 genes; Délye Reference Délye2013). Consequently, there is a significant risk that a particular P450 gene could show cosegregation with a resistance trait when, in fact, resistance is due to a different P450 gene that happens to be in close proximity within the genome.

Acknowledgments

The USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch project ILLU-802-923) provided partial funding of this research.