Since its introduction at the Royal Academy exhibition of Reference Richardson1891, Luke Fildes's painting The Doctor has earned that often hyperbolic adjective “iconic.” Immediately hailed as “the picture of the year” (“The Royal Academy,” “The Doctor,” “Fine Arts”), it soon toured the nation as part of a travelling exhibition, in which it “attracted most attention” (“Liverpool Autumn Exhibition”) and so affected spectators that one was even struck dead on the spot (“Sudden Death”). Over the following decades it spawned a school of imitations, supposed companion pictures, poems, parodies, tableaux vivants, an early Edison film, and a mass-produced engraving that graced middle-class homes and doctors' offices in Britain and abroad for generations to come and was reputedly the highest-grossing issue ever for the prominent printmaking firm of Agnew & Sons (Dakers 265–66).Footnote 1 When Fildes died in 1927 after a career spanning seven decades and marked by many commercial successes and even several royal portraits, his Times obituary nonetheless bore “The Doctor” as its sub-headline (“Sir Luke Fildes”) and sparked a lively discussion of the painting in the letters column for several issues thereafter (“Points From Letters” 2, 4, 5 Mar. 1927). Although the animus against things Victorian in the early twentieth century shadowed The Doctor it never eclipsed it; by the middle of the century the painting was still being held up as the quasi-Platonic ideal of medical practice (“Bedside Manner,” “98.4”), gracing postage stamps, and serving ironically as the logo for both a celebration of Britain's National Health Service and a campaign against its equivalent in the United States.Footnote 2 Appreciation of the painting in mid-century art historical circles was echoed in the popular press (“Victorian Art”), and The Doctor was singled out as a highlight of the reorganized Tate Gallery in 1957 (“Tate Gallery”), after which it settled into a sort of dowager status as a cornerstone of that eminent collection, where it is still in the regular rotation for public display. Since the mid-1990s it has been a recurring focus of discussion in both Medical Humanities journals and prominent medical professional organs such as the Lancet and the British Medical Journal, where a steady stream of articles still cite it as a sort of prelapsarian benchmark for the role and demeanor of the ideal medical practitioner.Footnote 3

This immediate, powerful, widespread, and enduring appeal is striking and not easy to account for. In an otherwise admirably nuanced reading, Michael Barilan attributes it to a “simple and straightforward iconography – a doctor attending at the bedside of a sick child. . .a universal, humane language. . .presenting no gaps or riddles that call for explanations” (59), and Abraham Verghese similarly asserts that “the painting resonates because all viewers. . .desire to be cared for with [that] kind of single-minded attentiveness” (122). But such universalizing explanations beg the question why other Victorian paintings that employ similar imagery have not enjoyed anything like The Doctor's success, even though many of them also debuted in Royal Academy Exhibitions and were likewise disseminated as commercially produced engravings. I will argue here that Fildes's painting caught fire while similar predecessors and successors fizzled not so much because it deploys universal archetypes or appeals to timeless human desires, but rather for two more specific reasons. The first is that Fildes's doctor appears to wed the authority and efficacy of a professional with the self-sacrificing nurturance of a parent, two powerful paradigms that were otherwise perceived as vexingly divided along the infamous cash nexus, one handsomely paid, the other supposedly beyond price. The second, related reason for The Doctor's unique eminence is that the specifics of its commission, format, public presentation, and role with respect to the professional status of its creator place the picture in a position unparalleled among Victorian paintings. Although, as we shall see, there were other Victorian pictures that likewise represented the otherwise very private sickroom scene in the very public terms of a prominently exhibited painting, Fildes's picture was alone not only in representing a doctor's attendance in a humble home, but also in couching that representation in formal terms that are conventionally heroic. This essay, then, will analyze The Doctor on two levels. First it will argue that the painting's use of, and contribution to, a specific subset of the developing iconography of Victorian narrative painting both reflected and helped to shape an evolving medical professional identity over the latter third of the nineteenth century. Second, the essay contends that the circumstances of the painting's production and reception effectively gave its creator a public-relations makeover, taking an artist who at the time was all too easy to dismiss as merely a fashionable sellout and recasting him instead as an altruistic champion of the voiceless and disfranchised. The Doctor, as we shall see, thus stands at the eye of a perfect storm of cultural-historical currents, ultimately emerging as a prominent and enduringly popular reference point not only for a supposedly self-sacrificing medical professionalism in particular, but also for an altruistic, nurturing, and heroic professionalism in general.

The Sick Child and Victorian Genre Painting

In order to understand what is exceptional about The Doctor, we must first understand a baseline context against which such exceptionality would have been perceived when the painting first appeared. There are of course many aspects to such a context – including the history of the medical professions in particular and professionalism in general (about which more in a moment) – but perhaps the most obviously relevant reference point is the tradition of sickroom representations that developed in British popular culture over much of the nineteenth century, including but by no means limited to painting, and often focusing especially upon sick, dying, or recently deceased children.Footnote 4 Besides The Doctor, other notable paintings in this vein (most of which also appeared in Royal Academy exhibitions and many of which were also reproduced as engravings) include Joseph Clark's companion pictures The Sick Child and The Sick Boy (1857); Thomas Brooks's Charity (1860) and Resignation (1863); Alexander Farmer's An Anxious Hour (1865); Frank Holl's The Convalescent (1867), Doubtful Hope (1875), and Her First-Born (1876); Thomas Faed's Worn Out (1868), Mother's First Care (1873), and The Doctor's Visit (1889); Frederick Daniel Hardy's The Convalescent (1872); John Everett Millais's Getting Better (1876); George Elgar Hicks's A Cloud With a Silver Lining (1890); Arthur Burrington's A Bribe (c. 1893); Henry Herbert La Thangue's The Man With the Scythe (1896); and William Small's The Good Samaritan (1899). We would do well, then, to begin an analysis of The Doctor by establishing a trajectory of nineteenth-century narrative painting in general with special attention to sickroom scenes in particular, focusing upon a representative cross-section of the above-listed paintings. It is worth acknowledging an important caution at the outset, however: it would be reductive to generalize these interpretations too directly from one subset of paintings to painting in general or from painting as a whole to a culture in general, since individual artists of course have their own idiosyncratic perspectives and agendas rather than serving as mere avatars of a putative zeitgeist, and genres have their own conventions that do not necessarily aim to be solely or even primarily documentary, didactic, or polemical. So it is always difficult to sort out the direction of influence between individual works and the culture they both reflect and help to shape.Footnote 5 Furthermore, these images in all their complexity thwart a straightforward longitudinal analysis of a given thematic cluster, such as representations of medical treatment; such thematic elements never seem to fall along convenient chronological lines in which one motif, such as a doctor or a bottle of medicine, is treated in several successive paintings in such a way as to yield straightforward, univocal explanations. Duly noting such limitations, however, we nonetheless can track individual elements, their combinations, the moments at which they appear, and so on in such a way as to reveal patterns that raise questions and invite illuminating interpretation. In the group of paintings treated below, for instance, several iconographic elements emerge and recede, and their presence or absence, individually or in combinations, establishes a backdrop against which The Doctor's anomalousness can be perceived. The elements most prominently in question here are, as we shall see in a moment, the sick child, the nurturing parent, the bottle of medicine, the rustic cottage interior, and the professional medical practitioner.

The particular strain of narrative painting that ultimately dominated the British art scene for most of the nineteenth century was initiated in the century's first decades with the Scottish painter David Wilkie's pictures of cottage life that merged aspects of centuries-old Dutch genre painting with Hogarth's more recently popular English demotic illustrations. By mid-century, cabinet-sized paintings in this storytelling vein had surpassed the wall-sized historical tableaux that had previously been the most popular mode of British painting, and genre subjects gradually began to dominate the increasingly popular Royal Academy summer exhibitions. Narrative painting thus assumed a position alongside theater, the new mass-printed periodicals, and novels as leading representatives of that exploding phenomenon, popular culture.Footnote 6 Lacking verbal narrative's resources for establishing and developing dynamic characters in successive settings, narrative paintings instead focused intently upon single moments of time and relied upon a “range of cues which audiences could be expected to identify,” as Paul Barlow calls them (66), to convey those moments' significance. And as this visual vocabulary evolved throughout narrative painting's heyday, it was not, argues Martin Meisel, “a fixed set of signs or a closed system of iconic representation, but an expanding universe of discourse, rule-governed but open, using a recognizable vocabulary of gesture, expression, configuration, object, and ambiance” (11). This language took its general shape in British narrative painting as a whole, but it also formed several dialects in a series of subgenres. Significant among these offshoots is the sickroom scene that emerged at the middle of the century and reached a sort of apex in its last decade with Fildes's The Doctor, developing between those bookends its own dynamic vocabulary of visual elements and a series of complex syntactical combinations of them.

A good entry point for discussing such images is a pair of paintings by Joseph Clark from 1857–58: The Sick Child and The Sick Boy (Figures 14 and 15). The paintings share similar compositions as well as similar titles: both feature a group of figures clustered around a hearth with a sick child sitting to one side of center, a man bending over the child to the left and a woman leaning inward from the right. The different character and disposition of these otherwise similar elements, however, are significant. In The Sick Boy the patterned rugs, framed art, silver tea set, and well-dressed characters tag the setting as a middle-class home, whereas the mismatched rustic furnishings and coarse rug in The Sick Child tell us this is that staple of Victorian genre painting, a cottage scene among the rural poor. Lest the man's heavy coat and work boots fail to inform us that he is a poor outdoor laborer, the dead rabbit lying on the floor next to him (much like the fishing net strung from the ceiling in The Doctor) demonstrates that he hunts the food his family eats. And although both paintings represent care for a sick child, the forms and agents of that care are tellingly different. In the rural cottage, the man holds the child in his lap, hugging her to his chest while the woman leans forward with a bowl and saucer, ready to spoon-feed her. In The Sick Boy, however, neither of the adults touches the child, a point of contrast that could be seen as perpetuating what Susan Casteras flags as commonplaces among Victorian genre paintings: “paternal affection and solicitude for children” among the rural poor and its contrasting counterpart, “the impression of upper-class remoteness” (Victorian Childhood 16).

Figure 14. Joseph Clark (1834-1926), The Sick Child. Artist's etching after his own painting, ca. 1858. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 15. Joseph Clark (1834-1926), The Sick Boy. Oil on canvas, 1857. Sunderland Museums & Winter Garden Collection, Tyne & Wear, UK.

But the difference also lends itself alternatively to a less invidious reading. For one thing, in The Sick Boy, the man's white-haired age contrasts with the more youthful figures conventionally represented as parents not only in The Sick Child but also in innumerable other genre paintings,Footnote 7 and departure from such an established convention seems significant in a medium that depends so heavily upon a “range of cues which audiences could be expected to identify,” to borrow Barlow's apt phrase again (66). So we are implicitly encouraged to regard the man as someone other than the boy's father; the woman behind the chair is likewise older than the conventional parent, and her simple black dress, white cap, submissive demeanor, and subjugation behind the chair suggest she might be a servant. Another unusual detail that draws attention to itself and demands decoding is a pair of men's house slippers lying prominently on the carpet in the lower left foreground. Why draw such attention to a pair of slippers, one might ask, only to show them as conspicuously unworn by a man we might expect to wear them were he a member of this domestic circle? One plausible answer is that the slippers are here to tell us specifically that this man is not a resident but a visitor. The man could be an older, non-resident family member, such as a grandfather, but in combination with the painting's titular subject matter, his physical disposition lends itself readily to a reading of him specifically as a doctor: leaning toward the sick boy and gazing intently at him without touching him, seeming to interpret data and impart wisdom (a suggestion seconded by the rapt and deferential attention of the woman behind the chair), he strikes a distinctive pose that can be seen as another of those cues audiences would readily recognize, in this case the characteristic stance of the examining doctor. Indeed Clark even attests to the gesture's formulaic legibility in another of his paintings, Playing Doctors (Figure 16), in which a child's imitation of a doctor is crystalized in the single telling detail of her likewise bending over a doll and staring intently at it without touching it.

Figure 16. Joseph Clark (1834–1926), Playing Doctors. Oil on panel, 1881. Private collection.

Such focused, hands-off examination was recognized not only in narrative painting but also in the culture at large as the characteristic “repertoire” of the physician. As Christopher Lawrence notes: “Practice, physicians agreed, consisted in the exercise of what they called skill, but skill was not a manual activity. It was constituted by the ability, as one physician put it in 1670, ‘to exercise. . .a piercing Judgement.’ This could be done, he said, only by having a ‘large Comprehension of. . .subtle and numerous natures and things’” (166). The apparent exercise of such piercing judgment, then, implicitly brands Clark's visitor as one of the university-educated physicians who occupied the uppermost rung of the medical-professional ladder before the Medical Act of 1858 softened such distinctions. Physicians' practice consisted solely of examining, giving advice, and writing prescriptions, so they were purveyors of knowledge and advice rather than material goods or services and so were farther from retail trade than apothecaries, who could charge only for medicines, or surgeons, who charged for physical treatments. Although some physicians also qualified as surgeons or apothecaries and could therefore practice generally, more of the growing ranks of general practitioners were surgeon-apothecaries without a physician's qualification; the pure physician's practice was necessarily confined to wealthier clients and more populous areas, where physicians would often have been elite consultants associated with the local hospitals that arose steadily from the late eighteenth century onward. Popular prejudices about health care then as now favored more tangible interventions, in the form of a surgeon's dramatic procedures or an apothecary's concrete medicines, over a physician's more abstract commodities of judgment and advice. But consulting a physician – rather than, for instance, buying medicines from an apothecary – would have implied that a patient was both enlightened and economically secure, whereas recourse to the “Physician in ordinary to the Masses,” as one contemporary dubbed the apothecary (Prendergast 392), might suggest that the patient was of more humble material means and education.Footnote 8 Although the boy's parents are not visible in the physical field and temporal moment The Sick Boy represents, then, their presence is nonetheless implied as the providers not only of the comfortable home and elegant clothing we do see, but also of the highest standard of professional medical care.

Just as the offstage presence of otherwise absent parents is implied in The Sick Boy, so is the presence of visibly absent medical practitioners implied in The Sick Child, in this case by the corked-and-tagged bottle of medicine that stands on the mantle high in the picture's center, an element that becomes another of those conventional visual cues upon which narrative paintings rely so heavily. Although it seems these parents lack the material wherewithal to bring a medical practitioner into their home, they do appear to have consulted an apothecary, perhaps in his own shop, and to have sacrificed some of their hard-earned money for this medicine. Clark's pair of paintings strongly suggests, then, at least a perception of a class-based differentiation among types of care for sick children, showing less affluent families providing the bulk of care themselves, with only incidental recourse to medicine probably bought from shops, and more affluent families bringing in medical professionals for consultation in home visits. Although in actual contemporary practice the differentiation would have been less stark, Clark's companion pictures set something of a precedent in representations of medical attendance with the contrasted attributes of their similar-but-separate worlds.

Another painting from just over a decade-and-a-half later depicts a scene implied as a past event in Clark's The Sick Child: a poor parent's purchase of medicine for an ailing child. The painting in question is Frank Holl's Doubtful Hope (1875) (Figure 17), which shows a mother of meager means (her poverty is indicated by her humble clothing and the ragged carrying basket at her feet) with a sick infant in an apothecary's shop. Unlike the contemplative physician of The Sick Boy, the two medical practitioners pictured here are physically active, one of them (an older and well-dressed man, implicitly the apothecary) dramatically mixing a potion held close before his brightly lit face while the other (a younger and more moderately dressed man, implicitly an apprentice or assistant) writes intently upon what is likely a label for the kind of bottle we saw on the mantel in The Sick Child. In yet another difference from Clark's intently gazing doctor, these medical men are far from engaged with their patient and his mother, who sits between and before them but with her back turned to them while their gazes are likewise turned away from her. Whereas Clark's doctor was a comforting friendly presence, these men seem merely to provide commodities for sale, as emphasized not only by the apothecary's detached manufacturing of his medicine with nary a glance toward the ailing child, but even more forcefully by the coin glinting in the despondent mother's right hand, ready to be passed over the counter upon which lies an open ledger in the foreground, further emphasizing the financial dimensions of the transaction. This implicitly negative visual take on the whole affair is seconded by the painting's title, which indicates that the process is not only dehumanized and dehumanizing but also of questionable value or efficacy. One available implication here is that the kind of medical care to which the poor have recourse is a matter not of ongoing intimate relationships and humane concern, but rather of impersonal supply-and-demand mercantilism.

Figure 17. Frank Holl (1845-1888), Doubtful Hope. 1875. Oil on canvas, 1875. Private collection.

An exactly contemporary painting by an exactly contemporary painter – Luke Fildes, who was later most famous for The Doctor – provides some illustrative points of comparison and contrast to Holl's, as well as a point of departure from which to backtrack and accrue some of the over-arching nuance that has been scanted in the discussion thus far. At the same time Holl exhibited Doubtful Hope, Fildes offered The Widower (1875) (Figure 18), in which a father leans over a deathly pale child in his lap, tearfully kissing its limp hand as four other children mill around him. The scene is again among the humble poor in a rustic cottage like that of Clark's The Sick Child, but there is no mother here to share the burden of sickroom care as there was in Clark's painting, and the child here is more gravely ill, if not already dead. The picture interestingly echoes, in many significant respects, a popular painting of half a decade earlier, Thomas Faed's Worn Out (1868) (Figure 19), in which another laboring father sits asleep at the bedside of a sick child.Footnote 9 Although dawn streams through the window of Faed's humble garret, a candle still burns at the foot of the bed, indicating that this has been the kind of through-the-night vigil associated with dire illness. In both Fildes's and Faed's paintings of poor nursing fathers, we see neither the attending doctor nor the bottle of medicine that indicated recourse to professional medical assistance in Clark's The Sick Child, suggesting that both Farmer and Fildes see the nursing of children through illness as the exclusive province of parents in poor rural families, who either cannot afford professional medical care or choose, for some other reason not clearly indicated in the pictures, to eschew it.

Figure 18. Luke Fildes (1844-1927), The Widower. Oil on canvas, 1875. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

Figure 19. Thomas Faed (1826-1900), Worn Out. Oil on canvas, 1868. Private collection.

But once again, this differentiation is not universal, for it is not only Clark who disagrees; so do some of Faed's and Fildes's other colleagues of the 1860s and '70s. Thomas Brooks, for instance, shows a mother in a rural cottage nursing a sick child in Charity (1860) (Figure 20),Footnote 10 and although the husband/father is not present in the scene, she is hardly without aid: in addition to the well-dressed mother and daughter carrying a charity basket and a bible through the cottage door (thus justifying the painting's title), there is also a tagged bottle of medicine beside the mother on the table, much like the one pictured in the similar rural sickroom of Clark's The Sick Child, suggesting she does have both the wherewithal and the desire to consult an apothecary. And lest the nexus of this painting, Clark's pairing of The Sick Child and The Sick Boy, and Holl's Doubtful Hope suggest that apothecaries are patronized only by the poor, another two paintings from the 1860s challenge that hypothesis as well. One of them is also by Brooks and joins Charity as one in a series of his pictures whose titles signpost the Christian feminine virtues they depict (other titles include Devotion, Relenting, and Consolation). The one in question here is Resignation (1863) (Figure 21), in which a mother sits at the bedside of a child who has apparently just died, as indicated by the deathly pale and inert little hand that seems to have just released the mother's lying beside it on the bedclothes. The scene is evidently a bedroom, indicating that this is the kind of multi-room house occupied by the middle classes, and the patterned rug and stately furniture join with the mother's spotless and elegant clothing in seconding that economic testimony. (The setting of the scene at a bedside emphasizes another dimension not yet seen in the previous paintings discussed here but soon to be seen in others: an illness more grave than those suffered by the children who wear clothes and sit upright in chairs.) There is a professional-looking man here too, but rather than treating or examining the child, he is holding out a bible at this moment of trial, thus combining with the religious theme of this series of paintings to cast him more readily as a minister than a doctor. Medical intervention is nonetheless clearly indicated, however, by the now-familiar icon of the tagged-and-corked bottle of medicine, appearing here on the bedside table at the frame's rightmost edge. In a similar contemporary painting, Alexander Farmer's An Anxious Hour (1865) (Figure 22), a bottle of medicine likewise appears along with a mother keeping vigil over her sick child. Like Farmer's and Fildes's nursing fathers, this mother is alone in caring for her sick child, but unlike them – though like both of Brooks's mothers – she has the aid of a bottle of medicine, which stands, like the one in Clark's painting, clearly visible on the mantle behind her. Her economic status seems similar to, perhaps just slightly below that of the family depicted in Brooks's Resignation: the setting appears to be a comfortably appointed bedroom in a multi-room home rather than a single-room rural cottage, and the mother's silk dress and colorful patterned shawl, as well as the orange on the bedside table, are luxury items suggesting at least a solid middle-class status.Footnote 11 The seemingly class-based differentiation between buying medicine or consulting practitioners that appeared rather stark in Clark's pair of paintings thus becomes murkier in paintings of the following decade-and-a-half.

Figure 20. Thomas Brooks (1818-1891), Charity. Oil on canvas, 1860. Private collection.

Figure 21. Thomas Brooks (1818-1891), Resignation. Oil on canvas, 1863. Private collection.

Figure 22. Alexander Farmer (1825-1869), An Anxious Hour. Oil on canvas, 1865. Victoria and Albert Museum.

At this point we can identify patterns among iconographic elements and their combinations, and there are two such patterns we might see as culminating in The Doctor. First, although the medicine bottle appears in both middle-class and laboring scenes as well as scenes in which parents are alone and ones in which they are not, it never appears in a home scene simultaneously with a medical professional before The Doctor. One might posit a qualified exception to that generalization in the case of Holl's Doubtful Hope, where medicine is shown along with the professionals preparing and selling it, but in addition to the fact that none of the medicine in Holl's painting appears in the familiar corked-and-tagged bottle, Holl's scene also does not take place in a home. So, for all the divisions that prove fluid from one set of paintings to another, two remain fixed across this group of paintings before The Doctor: never do a doctor and a bottle of medicine appear in a home scene at the same time, and never does a doctor appear in a laborer's cottage. At least two implications regarding the world represented by these paintings might be drawn from these patterns of division: first, that whereas apothecaries might be consulted by both laboring and middle-class families, home-visiting practitioners operate exclusively among the latter demographic, or second, that bottles of medicine in middle-class homes originate in prescriptions written by visiting practitioners rather than shop visits like the one represented in Doubtful Hope.

There is one painting, again by Thomas Faed, that initially appears to be a near exception to both of these patterns of division; initially titled Hush! Let Him Sleep (1889), it was retitled The Doctor's Visit in 1897 (Figure 23). In it, the door to what appears to be a one-room cottage stands open to the outside, where a professional-looking visitor waits just outside the door, face-to-face with a woman who stands athwart the threshold and holds the door from within, blocking his entry. In the foreground is a sickroom scene with another woman sitting beside the bed of an ailing man. The painting's revised title leaves no doubt that this visitor is a doctor, and we might assume the woman at the door is on the verge of welcoming him in, were it not for the original title's strong suggestion that she is actually turning him away – or at least requiring that he silence himself before entering. That Faed chooses to represent the titular subject of a doctor's visit with this inside/outside division is perhaps ironic, undercutting expectations of the visit's efficacy by emphasizing instead its disruption of an otherwise familiar domestic scene. It is as if the doctor of Clark's The Sick Boy has left his natural middle-class habitat and is attempting to invade the rural laboring scene of The Sick Child. Such a visit would encroach upon the norm of laboring families caring for one another and resorting to professional medical care only in the form of the bottled medicine we see again here in Faed's painting, standing on the cabinet above and behind the seated woman's head.

Figure 23. Thomas Faed (1826-1900), The Doctor's Visit (orig. Hush! Let Him Sleep). Oil on canvas, 1889. Queen's University, Belfast.

“The Sense of What We Ought to Be”

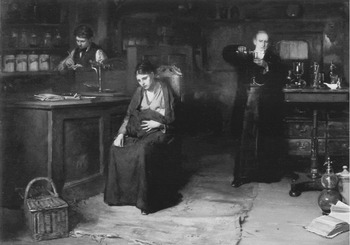

If Faed shows the doctor unsuccessfully attempting to cross what had theretofore seemed in paintings to be a sort of cordon sanitaire between the implicitly affluent, home-visiting medical practitioner and the rural cottage family, Fildes's The Doctor (Figure 24) shows not only that the boundary has been breached but that the doctor is even occupying and ruling the captured territory. The solicitous laboring parents who cared exclusively for the ailing children in The Sick Child, Worn Out, and Fildes's own The Widower have not only been superseded here but have also been relegated so deeply to the background shadows that many viewers fail even to notice them at first glance, and some printed reproductions obscure them altogether. As Fildes himself said of the eponymous doctor, “He should be the actor in the little drama I had conceived – father, mother, child should only help to show him to better advantage” (How 126). And the role the doctor plays in this prominent position looks, at first glance, very much like the role of nursing mothers and fathers in previous paintings, especially those of Worn Out and An Anxious Hour: like those concerned parents, the doctor keeps a through-the-night vigil at the bedside (dawn light peeps through the window to the right while a lamp still shines from the table to the left), and like Farmer's mother in particular he stares intently and hopefully at what seems to be a gravely ill child. One might ask, then, what this doctor provides that the parents cannot. There is more than one answer. First, the doctor does not merely stare hopefully; his gaze is the intense one of diagnostic inquiry we saw with Clark's doctor in The Sick Boy (and his pretend one in Playing Doctors). He also exhibits other specific doctorly attributes codified by longstanding convention in medical portraits. Sitting with chin in hand, he assumes what Ludmilla Jordanova describes as a sort of de rigueur pose in medical portraiture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: “a full-length or three-quarters seated position, next to a table, with head on hand. What this achieves is a pensive, contemplative quality, with its own form of denial. This is not a man of action, but a man of thought” (111). Fildes thus establishes the doctor as a learned and deep-thinking man, but counter-balances the accompanying connotations of inaction by combining the chin-in-hand pose with a straining forward posture suggesting action (or at least readiness for it), and setting the scene as one of medical attendance rather than the idealized library of the conventional portraits Jordanova describes. It is also significant that the doctor appears here in a setting that emphasizes manual labor: the fisherman's net, by means of which the anxious father presumably supports his family, hangs from the rafters, just barely visible in the background shadows. Thus not only does the doctor's care-giving implicitly supersede that of the child's parents; his intellectual/professional work also proves more pointedly efficacious in this life-or-death moment than does the superficially more active manual work of the laborer. The doctor's beard, too, is a significant detail that also emphasizes his assertively active and powerfully masculine nature: as Christopher Oldstone-Moore notes, the end of the century was a moment when “the man who embodied the ideal manliness of physical assertion and moral restraint was a bearded man” (28).Footnote 12

Figure 24. Luke Fildes (1844-1927), The Doctor. Oil on canvas, 1891. Tate Gallery.

This doctor is not passively hoping like Farmer's mother, then, but is instead actively scrutinizing and diagnosing his patient, watching for the appropriate moment for the appropriate action. What that action might be, however, is another question. The diagnostic pose suggests he is a physician, and the action resulting from the diagnosis – at least at times other than a moment of crisis such as this one – would presumably be to recommend a course of treatment or to write a prescription. With respect to these two possibilities, two other visual details emerge as significant, the first one new and somewhat enigmatic and the second one familiar by now. The new detail is on the floor in the foreground: two crumpled fragments of paper that at least one observer has assumed are “most probably a filled prescription” (Barilan 64). If the torn paper is indeed a prescription, that it lies crumpled and seemingly discarded on the floor suggests that prescribing has run its course and been left behind, perhaps even with a degree of frustration. The second, familiar detail stands in tension with the first: the now familiar bottle of medicine, which is positioned in a way that might make it seem either emphasized or downplayed: it stands in the foreground beneath the lamp that is the chief source of light in the picture, but it is also far to one side of the picture's frame and almost in the penumbra of the lamp's tilted shade. That it is here at all is significant, however, given that no painting we have seen before this one has placed a practitioner and a bottle of medicine together in any home. It might be that this doctor is a general practitioner, preparing and dispensing medicine as well as prescribing it, in which case we might see the medicine as a benefit the medical practitioner confers that parents cannot. Such a reading would run counter to the bottle's strong association in previous paintings with parents' ability to supplement their own active care, though, since in this instance it is implicitly not the parents who administer the medicine. The bottle sits firmly within the doctor's area of the composition, near a cup and saucer at his elbow that we might assume he has used to administer it, and which elements in turn contrast with the humble basin and ewer on the rustic bench near the child's head, away from the doctor and in the parents' side of the frame. Alternatively we might see the medicine as at least somewhat downplayed, cast to the side and almost into the shadows, standing not so much in apposition to the doctor as in contrast to him, the artifact of previous and failed attempts at medical intervention in the form of an apothecary's medicine now pushed aside by the physician's less tangible powers.

As noted, these powers of the physician had been long associated iconographically with the paradoxically inactive action of thinking and diagnosing, but by 1891 when Fildes produced the painting, a scene of practice such as this one would have lent itself readily to more concrete visual indices of the medical practitioner's power: the technological tools of scientific medicine that had become, as one medical textbook of the period called them, the “indispensable accompaniments of the physician”: “The hypodermic syringe. . .the stethoscope and thermometer” (Aitken 2: 115). The conspicuous absence of such technology here has consequently proven to be something of a watershed in one line of interpretation. Medical professionals in our own time tend to view the doctor's freedom from scientific apparatus in the painting as marking a moment just before medicine turned a corner toward what is now a deplored norm: “a style of practice that is heavily dependent on technology and that is so specialized that care is necessarily fragmented” (Verghese 124).Footnote 13 By polarized contrast, the eminent physician Benjamin Ward Richardson regarded the painting at the time of its debut as indicating that medicine was not yet technological enough:

[I]t suggests too faithfully a painful scene, which our art ought to be able to laugh to scorn, as too monstrous to be possible. . . .[B]y showing how weak we are, the scene recalls to us the sense of what we ought to be. This doctor is a type of healer waiting to be evolved into something far grander and more powerful in his vocation. . . .[H]e has not yet learned enough, albeit he is dubbed doctor. . . .[Fildes] marks for us, as it were, a new starting-point, from which we ought to set forth the more vigorously towards accession of power, with more certainty, more practical assurance of safe intervention, and more of the quality of positive skill, based on a scientific method, as exact as it should be triumphant. (Richardson 188–89)

Standing somewhere between these poles is another of Fildes's contemporaries, this time from outside the medical profession: the journalist Harry How. He sees the doctor as poised between scientific and homely means of treatment: “He is wondering how science can meet the little one's wants. Still he keeps the cup on the table close at hand” (117). The early twentieth-century art critic Roger Fry, like Verghese and other doctors of the early twenty-first century, also notes the absence of any conspicuously scientific apparatus or activity in the painting, but unlike Verghese et al., Fry regards this lack as a sign of the painting's specious sentimentalism: “In the doctor in particular,” he says, “there might be something of a purely professional scientific reason; he could not be, should not be, so purely, so nobly pitiful” (398).Footnote 14

Perhaps even more puzzling than technology's absence, however, is the doctor's presence. As others have noted, “the setting strongly suggests that the physician can expect relatively little monetary reward in exchange for his hours of lost sleep” (Brody 589),Footnote 15 so one might well ask why he is here at all. Perhaps the most ready explanation is in terms of a longstanding ideal expressed representatively by the novelist Ellen Wallace in 1849: “a medical man, who habitually gives his skill and labour to the poor, as so many do, without the slightest chance of remuneration, often without even the recompense of thanks, is fulfilling one of the divinest laws of our religion” (1: 277–78). Medical professionals themselves not only embraced this self-sacrificing role but preached it to newly matriculating medical students in introductory addresses, a “species of discourse [that] takes the sermonising form, and lectures ‘the young gentlemen we see assembled around us’ upon the conduct most proper to be pursued during their career,” as one mid-century observer characterized the increasingly formulaic genre (Hunt 138). As explicit conduct lessons, these addresses tell us much about the prescriptive if not descriptive self-conception of ideal medical professional identity at mid-century, and a number of them from the 1850s in particular give a composite picture of the model medical man as a self-sacrificing nurturer whose proper sphere is above the field of commerce and within the private home, not of his own family but of others.Footnote 16 The eminent physician Charles West, for instance, advises the entering class of 1850 at St. Bartholomew's Hospital that

you serve the state in a private capacity, and err if you expect public rewards. Your place is not in the busy mart, or the thronged arena, but in the silence and the solitude of the sick chamber; your heroism is not displayed before a crowd of spectators, nor are the fortunes of a nation dependent on its issue, – but you encounter disease, and expose yourselves to contagion, and run the risk of death, to save, if possible, a single life; and with no other witnesses than your patient, and the few friends who gather round his bed. But high as may be the intrinsic worth of deeds such as these, it must, I think, strike you, that their merit would be lost, if among the motives to them were admitted the expectation of large wealth, or the desire of worldly applause. . . .The benefits you confer are on the individual, and through the individual on the community; the honours you may attain to are not such as titles would enhance, they are the higher honours of personal respect, and gratitude, and affection. (27-28)

West's contrast of “private capacity” against “public rewards,” and parallel opposition of “the busy mart, or the thronged arena” to “the silence and the solitude of the sick chamber,” are strikingly similar to Sarah Stickney Ellis's oft-invoked opposition of “the mart, the exchange, or the public assembly” to “domestic life” (17). The parallels extend also to the rewards that supposedly accompany both women's and doctors' access to the domestic sanctum sanctorum: not “large wealth, or. . .worldly applause” but “the higher honours of personal respect, and gratitude, and affection.” West appeals here to a distinction noted also by Mary Poovey, who argues that during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “the segregation of the domestic ideal created the illusion of an alternative to competition” (10).Footnote 17 Thus the increasingly prominent ideology of the separate spheres both elided and highlighted rifts within the logic of medical care as an industry: Angel-in-the-House conceptions of caretaking as a feminine activity would place male medical professionals at a public-relations disadvantage, given that their role as caretakers would read more readily as feminine than as masculine, and their primary sphere of the domestic realm would distance them from familiar models of a publicly active masculinity that were more readily available to military officers, parliamentarians, captains of industry, etc.Footnote 18 But on the positive side, because men were by default expected to be focused upon economic competition, male doctors could appear to have selflessly renounced the more public glory and greater remuneration otherwise available to them in favor of the seeming ascetic martyrdom of medical practice, the ideal to which West points.

Despite these ready terms within which the doctor might be seen as an almost Christ-like representative of self-sacrifice, offering his professional services without a chance of even supporting himself materially, the reality was, predictably enough, more nuanced. Rather than making sacrifices to treat the poor, most medical practitioners actually depended upon a broad and economically diverse patient base rather than a narrow and well-to-do one. By 1834, as Parry and Parry note,

There were many persons with university degrees practicing in the provinces whose work was largely comprised of surgery, midwifery and even pharmacy. . . .These well-trained doctors could by no means secure an adequate livelihood simply by treating the wealthy. They began to enter general practice based principally on the market offered by the rising middle class, though they also gave their services to those rather less well off, through the mechanism of the differential fee. The better off patients were expected to pay higher fees than the poor, and for this purpose the doctor attempted to make some assessment of the ability of each patient or family to pay. (105–06)

So, far from representing a certain loss, practice among the poor was actually a potential asset for many doctors in at least two ways: it could both fill otherwise unbillable hours with work that at least paid something, and it could fuel word of mouth about the doctor's supposedly charitable nature along the lines traced by Wallace. The frequency with which doctors treating the poor were represented as self-sacrificing, then, attests to the power of that largely counter-factual notion.

“Something that Would Worthily Represent Me”

Fildes's presentation of a professional man who appears to blend masculine authority, material success, and heroism with a selfless humanitarianism was as much an expression of his personal ambitions as it was a projection of an ideal medical practitioner. Although his first big professional break came when he was commissioned to illustrate Dickens's last, incomplete novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), he secured his initial reputation as one of the mavericks (along with Herkomer and Holl) of a new social realism with both his illustrations for the reformist weekly newspaper the Graphic and his hugely successful painting Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward (1874). The considerable impact of Applicants arose largely from its jarring juxtaposition of public display (its subjects stand in a London thoroughfare beneath the glare of a gaslight) and private suffering (whole families, who by popular convention would ideally be basking round the hearth, instead huddle hungrily together against the harsh weather). When it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy it caused such a stir as to require police protection, as thousands of viewers thronged to scrutinize a scene many of them would have avoided in the streets (Thomson 24). In the '80s, Fildes gradually turned his critical success to more lucrative ends by producing popular idyllic scenes of Venetian life and accepting commissions for fashionable portraits, ultimately becoming one of the highest-paid portraitists in England and numbering members of the royal family among his subjects. As Fildes himself admitted, however much his social-realist paintings might have helped to establish his reputation, they were not as saleable as lighter subjects. Speaking later of his move to Venice he said, “people were beginning to chide me. Why were my pictures always so gloomy? How could I expect such subjects to go with the curtains in the drawing-room? So I thought I would paint a strong dramatic picture in pleasant places” (How 125).

The potentially negative implications of a shift from idealistic work that arose from humanitarian compassion to more lucrative endeavors that flattered the subject and lined the pockets of the artist were not lost on Fildes. Having been born in the hungry forties and shaped by the politics of the Lancashire Chartist grandmother who raised him, Fildes seems to have been plagued with guilt about his growing service to the rich and famous. And when, at the height of his fashionableness, Henry Tate commissioned him to provide one of the keystone pieces to inaugurate his new gallery of British art, Fildes jumped at the chance to redress the nagging imbalance and re-establish his credibility as a socially conscious professional. “Since you first spoke to me on this subject a few years ago,” Fildes wrote to Tate, “I have looked forward to the opportunity of producing something that would worthily represent me. . . .It is some time now since I painted an English subject of importance – a long time since The Casual Ward, The Widower and The Return of the Penitent series, and my strong desire is. . .to do it for reputation's sake.”Footnote 19 Fildes, then, regarded Tate's commission as an opportunity to return to his earlier social-realist ideals, thereby buffing up his tarnished image as an altruistic artist, even though he would be well paid for his renewed charitable efforts. Clearly sensing some contradictions, Fildes somewhat defensively downplayed the handsomeness of the commission, emphasizing at the time that The Doctor “quite prevents me from taking up anything else while it is in progress. I should probably make more money by portraits, which I have to entirely give up after making a success, to go on with this commission. So with one thing and another the price [£3000], from my point of view, is not excessive.”Footnote 20 Julian Treuherz has said The Doctor is “as much about the devotion of the professional man as about social injustice” (183), and Paula Gillett has sharpened the point, emphasizing the parallel between the professional artist and his professional subject: “[Fildes] was at once celebrating his own high professional status. . .and suggesting. . .that the upholding of professional ideals was for the painter, as well as the physician, a social service” (120). This move back toward a seemingly more socially conscious stance seems to have had its intended rehabilitative effect among Fildes's contemporaries as well: “The painter might have gone on with his facile and fascinating Venetian subjects – they never failed to please the public whom a painter must respect, the public who buy,” said a critic shortly after the painting debuted; “But Mr. Tate's commission enabled the artist to do work more worthy of his old reputation.”Footnote 21

The genesis of the painting's doctor figure reinforces this parallel between compassionate doctor and altruistic painter. Fildes did not rely exclusively on one model and even apportioned what was regarded as a privilege, sitting as a model for the saintly doctor, among a bevy of clamoring medical professional friends, “though for the principal figure, the Doctor himself,” says his son, “he acted the part and was photographed in the pose for the guidance of future models” (Fildes 118). Indeed, despite the fact that, as Fildes himself said, “‘The Doctor’ was painted practically from a model with a clean shaven face” and ultimately “. . .compiled, from five or six persons” (How 126), the bearded countenance of the finished figure looks strikingly like Fildes himself, as several contemporaries also noted (see Figure 25),Footnote 22 thus lending extra resonance to Fildes's wish that the painting would “worthily represent me” (qtd. Fildes 108). By casting himself as the heroic, self-sacrificing professional, attentive to the sufferings of even a single poor child and endowed with significant powers to mitigate them, Fildes was implicitly striving for “congruence between his past and present identities” (Gillett 120), trying to close the gap between the hungry social realist, championing the underdog while struggling to make ends meet, and the prosperous portrait painter, living comfortably off of commissions from the rich and famous while abandoning the voiceless poor he had previously championed. Fildes explicitly acknowledged this desire to return to his former glories, saying to David Croal Thomson while planning The Doctor, “Do you remember ‘The Casuals,’. . .and ‘The Widower’ and ‘The Return of the Penitent’? Well, to me, the new subject will be more pathetic than any, more terrible perhaps, but yet more beautiful” (Thomson 12).

Figure 25. Photograph of Luke Fildes (1844-1927).

It is especially telling, then, that Fildes chose a doctor as the persona best suited to this purpose. Why not cast himself, for instance, as a cleric ministering to the poor he had immortalized in Applicants? His choice of the doctor is, as he himself put it, an eloquent “record [of] the status of the doctor in our own time” (qtd. Wilson 90), testimony to the unique associations of the medical man in late-century culture with heroic self-sacrifice and relief from suffering. And these heroic implications are ingeniously reinforced by a physical attribute impossible to perceive from reproductions: at nearly five feet by eight feet, the canvas presents the intimate subject matter of a domestic genre scene in the enormous format of the epic historical tableau. This surprising amalgamation of genre subject and historical format resonantly reinforces contradictions in the doctor's otherwise jarring breach of the family circle, casting as heroic apotheosis what in cabinet dimensions might have seemed a mere lapse of decorum. It also reflects upon the status of the artist's own labor. As Tim Barringer notes, the work of the Victorian artist “could be understood not only as not respectable, because not related to approved forms of labour, but also not conforming to socially approved conceptions of the masculine, as effeminate” (154). This stigma, combined with the fact that “[a] combination of demand in the marketplace and social convention determined that women artists tended to produce small-scale paintings of domestic subjects” (Barringer 155), tended to associate cabinet-size genre paintings with a private and feminine rather than a public and masculine form of labor. Mid-Victorian artists such as Ford Madox Brown fought against these negative associations, argues Barringer, by placing renewed emphasis upon conspicuously accomplished brushwork, thus highlighting the actual physical labor of artistic work. But “[b]y the 1890s, artistic practice had come, in avant-garde circles, to be regarded as the polar opposite of work” and “[t]he Ruskinian and Carlylean moment, in which self-consciously manly artists labored after a hard-won realism and produced so many morally charged representations of labour, had passed” (Barringer 164–65). At this crucial turning point, then, Fildes innovatively spearheaded a new association of painting not with manual labor, as was the trend at mid-century, but instead with the heroic and selfless ideal of professional work. It is telling in this light that the visual reference point for manual labor in The Doctor is a nautical one, the fisherman's net hanging from the cottage ceiling, given that Fildes's father made his living as a mariner and shipping agent (Davis). Thus the painting simultaneously pays tribute to the artist's labor-based origins and silently attests to the distance the painter, implicitly allied with the doctor, has risen above them. “I come from a stock who knew very little about artists,” said Fildes in 1893, “whose only notion of an artist was the traveling portrait-painter who in those days put up at the local inn, drank and got into debt, and had a poor, long-suffering wife with a quiver full! So my grandmother was not impressed with the notion [of her grandson's being an artist]. She suggested something more substantial” (How 118). Fildes ultimately measured up to his grandmother's vocational expectations for him not by taking up a more substantial field than art, but by taking up art and making it a more substantial field.

At least as much as Fildes's painting reflected cultural associations of doctors with heroically selfless professionalism, it also perpetuated and strengthened them, even providing the subsequent yardstick for ideal medical professional identity as preached in the aforementioned garden-variety address to medical students. “What do we not owe to Mr. Fildes for showing to the world the typical doctor as we would all like him to be shown – an honest man and a gentle man, doing his best to relieve suffering?” asked the surgeon W. Mitchell Banks of an incoming class at the Liverpool Royal Infirmary in the year following the painting's hugely successful debut. “A library of books written in your honour,” he said, “would not do what this picture has done and will do for the medical profession in making the hearts of our fellow men warm to us with confidence and affection. . . .[W]hatever may be the rank in your profession to which you may attain, remember always to hold before you the ideal figure of Luke Fildes's picture, and be at once gentle men and gentle doctors” (Banks 787–88). Even Benjamin Ward Richardson, who (as noted above) regarded the painting as a painful reminder that medicine still had a long way to go toward scientific advancement, similarly praised the picture for showing “not a doctor, in the original sense of a learned man, but an earnest, sympathetic, and thoughtful attendant on the sick” (186). And it was not only medical professionals themselves who regarded Fildes's doctor as this kind of ideal practitioner, but also the lay public. “Many are the letters I have received asking for the name of ‘the doctor,’” said Fildes in 1893, “whilst one came from somebody who was ill, assuring me that she would be very thankful to have his address, for if she only had a doctor like him to attend her she felt sure she should soon get better!” (How 127).

As for the effect on Fildes's own subsequent career, his most popular painting seemingly enabled him to ascend into an almost non-material realm of ideally compassionate and selfless professionalism. As his son relates,

Years after The Doctor's appearance my father was up in town one day and he hailed a taxi to take him home to Melbury Road. Arrived there, he was about to pay the fare when the driver, who had been looking up at the house, asked:

The anecdote suggests that the cabman has driven a cognitive wedge between the painter of The Doctor and the world of commerce, but also that practitioners of other professions and trades (the non-charging cabbie himself in the anecdote) aspired to replicate The Doctor’s ideal of selfless, unpaid service. The legacy of Fildes's painting thus suggests that, unlike otherwise similar paintings by contemporaries, The Doctor enabled at least the impression that a delicate balance among commerce, nurturance, and professionalism was possible. Fildes thus drew power from the tension between domesticity and commercialism at the heart of medical professional duty and authority, but he also fed some back in. His resonant image of the compassionate doctor, who blends the public sphere of commerce and the private sphere of domestic nurturance in the hybrid figure of the heroic professional servant who is above pecuniary considerations, has served as a perhaps illusive but undoubtedly powerful memento of an imagined golden age in both his own cultural moment and in ones that have succeeded it, including our own.