Introduction

Hong Kong was a British colony from 1842, when the Qing Empire ceded Hong Kong Island to the United Kingdom, until 1997, when it was returned to China. During the first century of British rule, triad societies developed into an essential non-state urban power affecting not only the daily lives of lower-class citizens but also the stability and prosperity of the city. Since the creation of the Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC) in 1974, triad society power has declined, because under effective law enforcement senior triad members turned from running illegal businesses to mostly legitimate individual businesses in Hong Kong and mainland China. However, patriotic triad members came to public attention in the 2010s because of their involvement in repressing pro-democracy social movements and supporting the social and political status quo. This article examines the rise, fall and resurrection of triad societies in Hong Kong, paying special attention to how changes in the city's social and political life affected the evolution of triad societies and how triad societies interacted with politics in the past 180 years.

This article is structured as follows. First, it proposes a novel concept of ‘the urban criminal polity’, which defines urban criminal organizations as a non-state power in the city; it also explains the state's role in the emergence of organized crime groups and discusses a conceptual typology of organized crime–state relations. Second, it discusses our data collection methods and their limitations. Third, it outlines the origin of triads in mainland China. Fourth, it examines the rise of triad societies during Hong Kong's colonial era through the relationship between the criminalization of immigration and the development of triad societies and through triad societies’ relationship with the colonial government. Fifth, it explores the alliance between patriotic triad societies and the Chinese government in the post-colonial period, especially triad societies’ role in suppressing pro-democracy protests. It then summarizes the key analysis and concludes.

Criminal politics as an analytical framework

‘Polities’ consist not only of states, cities and state-sponsored political organizations but also of non-state, private, civil powers and authorities such as corporations, criminal organizations and families. A polity is a group of people who possess a shared belief system and a collective identity and who have the ability to mobilize resources and persons for shared objectives.Footnote 1 Hierarchy is a common way to structure such groups, using different levels of authority and developing institutional rules to regulate members’ activities and co-ordinate vertical and horizontal relationships. To enhance understanding of how a city is plundered by organized crime, researchers can view organized crime groups in cities as criminal authorities, or urban criminal polities, and examine their interactions with the state from a historical perspective.Footnote 2

The examination of the relationship of organized crime to the state requires researchers to pay special attention to the role played by the state in the emergence and development of organized crime groups. When the state is unable to protect private property rights and safeguard market transactions, alternative enforcement and protection mechanisms, such as mafia groups, emerge to fill the vacuum.Footnote 3 For example, in transitional countries such as China and Russia, a mafia – defined as a type of organized crime group specializing in the provision of protection and quasi-law enforcement – will emerge to protect property, enforce loan repayments and secure social transactions.Footnote 4 If a government imposes prohibition, which is ‘an extreme measure directed at the production, distribution and consumption of a good and service’,Footnote 5 this will give rise to the formation of illegal markets in which criminal organizations act as producers, distributors and consumers of illegal goods and services.Footnote 6 To maximize security and minimize the risk of capture, organized crime groups develop strategies such as recruiting trustworthy new members from pre-existing networks.Footnote 7 Risk forces criminals to use constitutions (i.e. written rules) to create common knowledge among members, co-ordinate rule-enforcement and prevent behaviour that harms organizational interests.Footnote 8 Risk also encourages criminals to employ rituals to create collective identity among group members, establish common knowledge about internal rules and solve asymmetric information problems.Footnote 9

Barnes suggests a ‘criminal politics’ analytical framework and proposes a conceptual typology of organized crime–state relations.Footnote 10 He distinguishes ‘between four crime–state arrangements that vary from confrontation (high competition), enforcement–evasion (low competition), alliance (low collaboration), to integration (high collaboration)’ (emphasis in the original).Footnote 11 On the competitive side of the spectrum, in confrontation, organized crime groups target the state and its agents while the state uses harsh repression to eradicate criminal organizations.Footnote 12 In enforcement–evasion, the state employs the criminal justice system to arrest and prosecute criminals while criminal organizations use (1) legal fronts to hide their illegal businesses,Footnote 13 (2) non-violent means to avoid state attentionFootnote 14 and (3) the corruption of police officers, prosecutors, politicians and bureaucrats to avoid enforcement and punishment.Footnote 15

On the collaborative end of the spectrum, alliance is where criminal organizations and the state establish mutually beneficial networks: pro-government or patriotic criminal groups reduce or conceal their violence and supplement state control and authority. The state reciprocates by limiting enforcement. Alliance is a proper strategy in which the state is ‘incapable or unwilling to take a more active role’ in combating non-state armed groups, regulating markets, curtailing violence and offering protection to citizens.Footnote 16 Integration, the highest form of collaboration, occurs when members of criminal organizations are incorporated into state agencies, enabling criminal organizations to engage in criminal activities with impunity,Footnote 17 and/or when state agencies get involved in illegal businesses to generate state revenue.Footnote 18 Barnes’ conceptual framework of organized crime–state relations offers insights into how criminal organizations such as Hong Kong triads interact with the state.

Methods and data

This article is based on a review of official documents, media analysis and relevant literature in both English and Chinese as well as interviews with triad members. Chinese-language books and articles written by leading Chinese historians such as Cai Shaoqing and Qin Baoqi are the main sources of data on the origin of Chinese triads. Colonial Office records, such as the Great Britain Colonial Office – Hong Kong: Original Correspondence (CO 129 series), are used to analyse the rise of triad societies and the government response to triad activities during the early years of British rule. The discussions on the development of triad societies and their interactions with politics in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are based on extensive literature and newspaper articles.

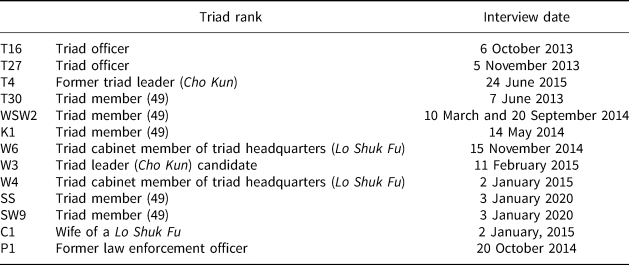

Interview data collected from 11 triad members, some of whom have since passed away, greatly assisted the understanding of how triad societies have responded to changing socio-political circumstances since the 1960s. The interview data is drawn from a series of ethnographic research projects, including the second author's doctoral research project on local triads (the research was done between 2013 and 2016) and her projects on the role of triads in the Umbrella Movement (data collected between September 2014 and March 2016) and the Anti-Extradition Movement (data collected between December 2019 and January 2020) (Table 1).

Table 1. List of interviews

Purposive sampling was used: participants were ordinary triad members and senior triad members including top-level officers, for example Lo Shuk Fu (cabinet members of the triad headquarters) and Cho Kun candidates (senior members who compete for triad faction leadership). For the purpose of triangulation, a law enforcement officer and the wife of a Lo Shuk Fu were interviewed to verify the data mentioned by the triad samples in the Umbrella Movement research.

To ensure that the participants were genuine triad members, only formally initiated triad members were selected. To select participants for in-depth interview, the legal definition of triad membership was used to screen suitable participants. The screening questions included (A) What is your triad rank and what triad society do you belong to? (B) Have you attended a triad initiation ceremony? (C) Have you pledged loyalty to any formal initiated triad member as your protector? These screening questions were set based on the criteria for defining triad membership in current legal practice.Footnote 19 Supplementary questions were asked about the basic structure of triad society and the form of the initiation ceremony in order to check participants’ knowledge about triads and reconfirm their triad membership. These questions were asked before audio recording of the interview commenced. The researcher also sought assistance from fieldwork gatekeepers to verify participants’ triad identity.

Empirical data was collected by the second author of this article in three ways: face-to-face semi-structured in-depth interviews, telephone conversations with triad members and fieldwork conversations. Informed consent from participants was sought beforehand for all forms of interview. For the face-to-face interviews, audiotape recording was used.

Empirical data collected through fieldwork conversations and telephone conversations presented a problem due to the difficulty of using professional audio-recording devices. Instead, these interviews were recorded by the researcher on her mobile phone, so that she could ensure the accuracy of the collected information, or recorded with voice notes when there were breaks during the interview. Research participants had the right to halt or delete the recording if they did not want any or part of the information to be recorded. If the researcher needed to quote the participants’ conversation in her research, she would seek their consent on the spot, asking them whether they would permit her to quote it in her research and ensuring that their identities would be kept in strict confidence. When the recorded interviews were transcribed, she not only asked the participants to verify the accuracy of information they had given but also asked the key informants to check the accuracy of the information collected in the fieldwork (during which the identity of participants was protected).

Due to the criminalization of triad membership and the illicit nature of triad organizations and activities in Hong Kong, gaining access to the research field and interviewees was very challenging. This research only managed to interview a limited number of senior triad members with rich knowledge of triad history and triads’ relations with the government. This led to some difficulties when we sought to triangulate our findings, reduce bias and improve validity. Another limitation of this research is that interviewees came from different backgrounds, and their perception and understanding of triad societies varied according to their triad generation, rank and age. Because triad operations are quite territory-based and time-specific, the empirical data collected across different periods could only provide snapshots of the phenomenon from each participant's perspective at the time of interview.

The origin of the Chinese triads

Drawing on Qing Dynasty archives, Qin Baoqi, a leading authority on the history of secret societies, offers a widely accepted explanation of the origin of the Tiandihui.Footnote 20 According to Qin, the Tiandihui was a mutual-aid and self-protection association of lower-class people founded in Fujian province in 1761 or 1762.Footnote 21 The Tiandihui and other secret societies emerged as quasi-governmental organizations because lower-class people's demands for protection and living necessities had been largely ignored by the Qing government.Footnote 22 The Tiandihui was intended to secure members’ survival in a hostile environment rather than the political aspiration of ‘overthrowing the alien Qing government and restoring the native Chinese Ming dynasty’.Footnote 23

During the great eras of Kangxi and Qianlong (1681–1796), the government's incentivizing policies of developing uncultivated land and improving farming methods led to an increase in agricultural output and rapid population growth.Footnote 24 According to Tian,Footnote 25 the total population quadrupled, from 102 million to 413 million, between 1685 and 1849. The negative impact of this rapid growth was enormous, however. Population growth far outpaced agricultural output, resulting in too little agricultural land per person, a complex system of multiple ownership and tenancy and an increasing number of landless and unemployed people. Inhabitants in Fujian province also suffered economic hardship caused by land scarcity. As Murray and Qin note, ‘whereas in 1571, the average landholding in Zhangzhou was estimated at 5.0 mu per person (6.6 mu = 1 acre), by 1812 the figure had shrunk to 0.93, well below the 4.0 mu needed for bare subsistence’.Footnote 26

Land scarcity compelled many to migrate to coastal cities to earn their livelihood, but these cities were unable to accommodate the migrants. The migrants faced starvation because they were socially isolated and unable to draw on support from their families, so they formed self-help and mutual protection groups – that is, secret societies.Footnote 27 Members of these secret societies were recruited into criminal activity, such as smuggling, extortion, robbery and trafficking, all of which threatened the safety of other lower-class residents. As the Qing government did not protect its citizens by repressing these secret societies, a large number of lower-class people had no choice but to join these societies.Footnote 28

Land scarcity also led to serious social conflict and violent incidents among sub-ethnic groups. According to the Gongzhongdang Yongzhengchao zouzhe (the Palace Memorial Archive of the Yongzheng reign), social conflict and violent incidents among different clan or lineage groups in Fujian province were a major concern.Footnote 29 In order to resist attacks from powerful lineage groups and protect property boundaries, members of smaller, weaker lineage groups became sworn-brothers and formed cross-clan or cross-lineage alliances. These groups developed into secret societies, including the Tiandihui. Taking advantage of the ever-increasing population, social disorder and severe economic hardship, the Tiandihui recruited many new members and established a power base in most cities in China, including Hong Kong.

Hong Kong triads during the British colonial era (1842–1997)

To understand the rise and fall of triad societies, as well as their relationship with politics during colonial rule, this section concentrates on two significant aspects: the rise and criminalization of Hong Kong triads and the dynamic relationship between triad societies and politics.

Criminalization and the rise of Hong Kong triads

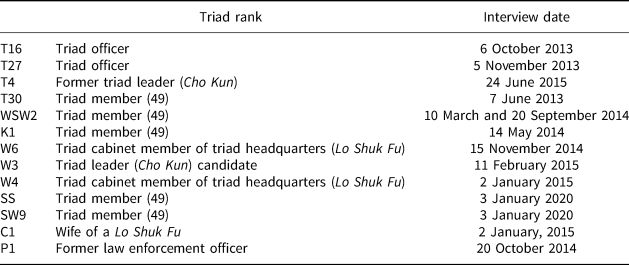

The Triad Society had established branches in Hong Kong before the Qing Dynasty ceded Hong Kong Island to the British empire in 1842. Soon after, the colonial government adopted European cities as a model to develop the northern coast of Hong Kong Island, which became the City of Victoria, the centre of the colony (see Figure 1). In order to solve the city's lack of human resources in its development, the colonial government ‘never implemented any policy that would prohibit the Chinese from entering Hong Kong’.Footnote 30 China's radical political and religious upheavals, such as the Taiping Rebellion (1851–64), compelled large numbers of people in Guangdong and Guangxi to migrate to Hong Kong. The colonial government focused on the city's commercial construction and largely ignored ‘the livelihood of the city's people, such as public order, food, housing and health’.Footnote 31 The absence of measures to address the Chinese population's social needs gave people no choice but to form and join mutual-aid associations.

Figure 1. Hong Kong – City of Victoria, 1932. Government Records Service, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, www.grs.gov.hk/en/index.html.

The colonial government noticed that ‘Triads made up a significant portion of early Hong Kong inhabitants’Footnote 32 and that triad societies harmed the good order of the colony and the security of life and property.Footnote 33 But the government faced significant difficulties, such as language and cultural barriers; most inhabitants were fishermen, peasants, cooliesFootnote 34 and stonemasons who distrusted the government and preferred to ‘cling more closely together and submit their problems and disputes to their elected head-men [most of whom were triad members] rather than the established authorities’.Footnote 35 The colonial government showed little interest in communicating with Hong Kong inhabitants and building trust. Instead, in January 1845, it enacted the ‘Ordinance for the Suppression of the Triad and Other Secret Societies within the Island of Hong Kong and its Dependencies’,Footnote 36 prohibiting membership and attendance at meetings of triads and other societies.Footnote 37

Criminalization of triad membership did little to repress the Triad Society. According to Carroll, the colonial government was determined to rule its Chinese inhabitants on the cheap. Chinese people therefore ‘had to rely on themselves and personal networks and to foster their own leadership to represent their needs and interests’.Footnote 38 As a consequence, lower-class people either joined existing triad societies or established new mutual assistance and labour associations that adopted the triad oath and ritual to bind their members more closely. The expansion of the Triad Society in Hong Kong was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it worked as a substitutive institution, supplying its members with what the colonial government declined to provide: protection, social welfare and basic living necessities. On the other hand, it empowered its members to earn money by extortion, robbery and other criminal activity, including brothels and gambling dens. As Colonial Office records show, many coolies were triad members who were ready to take advantage of any disturbance or opportunity.Footnote 39 Coolies who were triad members frequently extorted coolies who were not. For example, the official records of 1886 state that, after receiving their daily wage, every coolie at the Aberdeen Dock, one of nine harbours in Hong Kong, had to deposit 4 cents – ostensibly for a mutual-aid fund – in a box brandished by a Triad Society member.Footnote 40

In May 1886, the colonial government appointed a committee of three justices of the peace to assess the power and influence of triad societies in the colony.Footnote 41 The committee found that the number of triad members in the colony was between 15,000 and 20,000 (i.e. one tenth of the population) and that triad societies exerted enormous influence over the lower class.Footnote 42 Government tactics to suppress the secret societies included banishing headmen and active members, warning all law-abiding persons to leave these societies and offering a reward of $50 to any person who provided information about a person who returned from banishment.Footnote 43 Despite this, triad societies remained very attractive to lower-class Chinese.

Triad societies’ increasing role as an urban criminal polity in the colony also benefited from several waves of immigration. Carroll mentioned that ‘Hong Kong served as a haven for Chinese refugees: during the Taiping Rebellion (1851–64), after the republican revolution of 1911 and throughout the turbulent 1920s, after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, and after the Communist revolution of 1949.’Footnote 44 The population of Hong Kong grew from 90,000 in 1841 to 2,138,000 in 1951.Footnote 45 Despite the growing number of immigrants, the colonial government avoided spending on social welfare, worried that it would attract more immigrants fleeing China's wars, social disorder and unemployment.Footnote 46 Consequently, Chinese immigrants enduring sickness, poverty, unemployment and overcrowding received little official support in colonial Hong Kong.Footnote 47

Denied government support, Chinese immigrants banded together. As Chu noted, immigrants from the same district or region in mainland China ‘grouped together to form clan and district organizations for mutual aid’.Footnote 48 Most immigrants came from southern China, where many were members of the triads and other secret societies. Immigrants who joined the triads before their immigration favoured triad constitutions and rituals to regulate their organizations. One example was Fok Yee Hing, one of the oldest triad societies in Hong Kong. This was a sub-branch of the Tiandihui (Hong League), which migrated to Hong Kong in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 49 However, not all triad societies in Hong Kong were associated with secret societies on the mainland. For instance, Yee On, the predecessor of Sun Yee On,Footnote 50 was a trade association established by workers who came from Chiu ChowFootnote 51 but had no links with secret societies on the mainland; they formed the association in order to resolve conflict between entrepreneurs and workers, and adopted triad rituals for cohesion and internal control.Footnote 52

Between 1914 and 1939, seven main triad societiesFootnote 53 significantly affected the daily lives of the Chinese population. Each had ‘a headquarters branch and a number of sub-branches operating in their respective areas’.Footnote 54 These societies were no longer strictly associations. They developed into powerful criminal organizations, using legal fronts such as ‘trade guilds, benevolent associations, or sports clubs’ to hide illegal businesses, including extortion, illicit drugs, gambling, smuggling, prostitution and loan sharking.Footnote 55 They exerted enormous control over Hong Kong's labour markets, including the coolie industry, hawking, construction and public services. Labour associations not incorporated into the main triad groups either obtained protection from one of the groups or established their own triad-type association to resist takeovers.Footnote 56

Since the 1940s, a number of new societies showing no loyalty to any of the main triad groups have emerged to challenge the power of the older groups. Leaders of the old triad societies were unwilling to curb the development of new groups because to do so would require the use of open violence, which would attract police attention and increase the risk of being banished from Hong Kong.Footnote 57 The power of triad societies continued to grow until the establishment of the ICAC in 1974. This enabled the colonial government to solve the problem of corruption in the public sector and cut links between corrupt police officers and triad members.Footnote 58

The triads and politics

Drawing on interview data and the existing literature, this article finds that interactions between the colonial Hong Kong government and triad societies were primarily characterized by enforcement–evasion. Confrontation between the colonial government and triad societies occurred on only a few occasions, for example in 1884–85, 1925–26 and 1956 respectively, when triad societies in Hong Kong were mobilized by the Chinese government to resist colonial rule. During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong (1941–45), the Imperial Japanese government recruited pro-Japanese triad factions to maintain social order, collect intelligence and regulate illegal businesses. The recruitment of some triad factions by the Imperial Japanese government can be described as integration between the Imperial Japanese and these triad factions.

Enforcement–evasion

Throughout most of the colonial period, interactions between the government and triad societies followed the enforcement–evasion model: triad groups evaded law enforcement primarily by infiltrating the police force and bribing police officers.Footnote 59 These strategies did not lead to a collaborative arrangement between triad societies and the government at organizational level, however. Triad societies only managed to create alliances with individual police officers who were corruptible or were triad members.

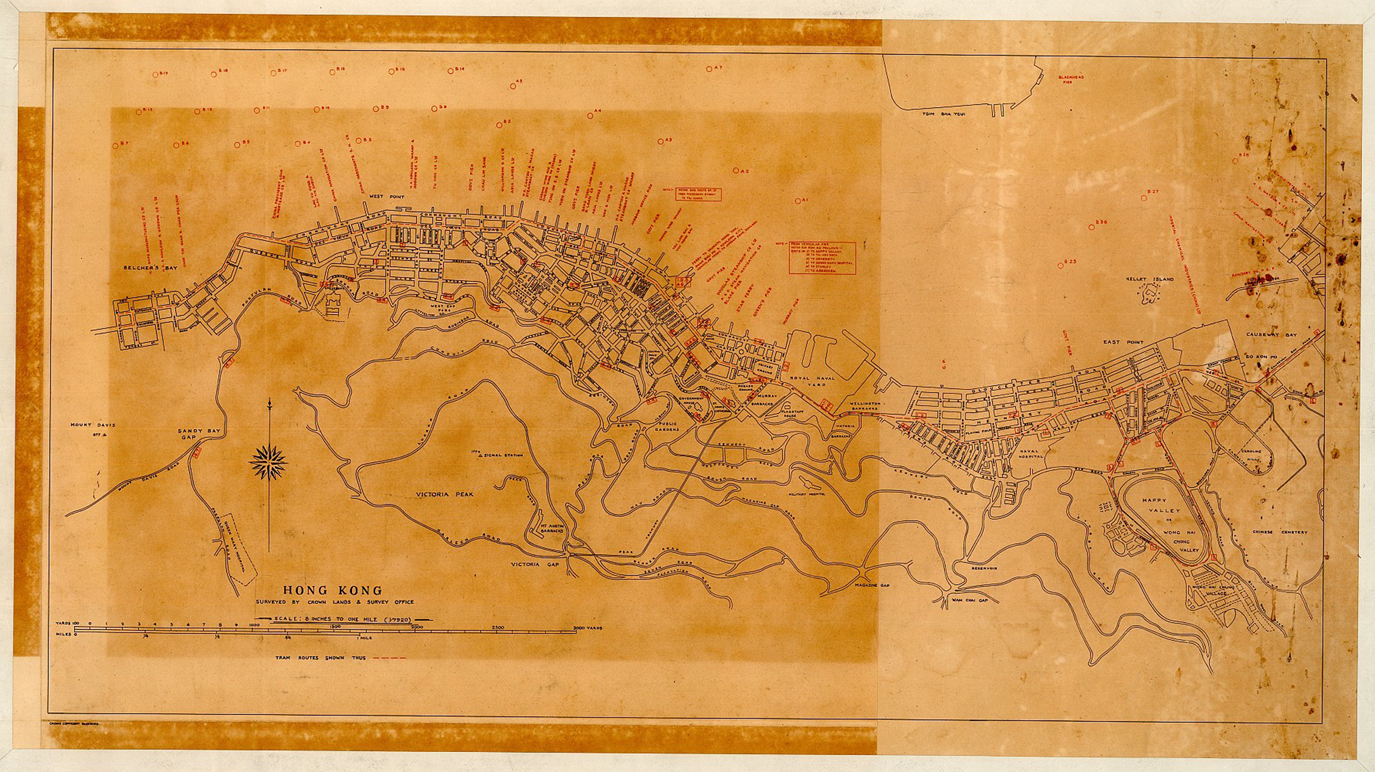

For the first century of the colony's history, the colonial government established its police force as a paramilitary force that resembled the police in other British colonies at the time, but its recruitment policy was different from all the other colonies: ‘a majority of the force [were] recruited overseas because it [was] believed that the security of the colony could not be safely entrusted to locally recruited Chinese policemen’.Footnote 60 The development of the police force in Hong Kong did not go smoothly. Early governors of colonial Hong Kong did not reach a consensus with the European merchants on the raising of revenue to establish a system of law and order. The European merchants perceived the creation and running of a system of law and order to be expensive and ineffective, and they argued that ‘the British parliament and British taxpayer ought to fund the cost of protecting and developing Hong Kong, since it was British trade along the entire China coast that benefited from the colony’.Footnote 61 As a result, the police force was founded and run with insufficient funding.

In 1845, the first police force in Hong Kong had ‘three London Metropolitan officers and 168 men (71 Europeans, 46 Indians, 51 Chinese)’.Footnote 62 In 1874, the land police in Hong Kong was composed of ‘110 Europeans (22 per cent), 177 Indians (36 per cent) and 204 Chinese (42 per cent)’, and this pattern of recruitment was maintained, with minor variations, until the Japanese invasion in the early 1940s.Footnote 63 The colonial government did recruit some officers locally, for linguistic and cultural reasons, but only to the lower ranks (see Figure 2). They were perceived by the government as being untrustworthy and having ties with triad societies.Footnote 64 In 1886, the owner of an illegal gambling house who was annoyed with continued extortion attempts made by the Chinese police reported police extortions to the colonial authorities, resulting in the prosecution and dismissal of 53 Chinese police officers, a quarter of the Chinese contingent.Footnote 65 In the same year, the captain superintendent of police forwarded the names of 10 persons whom he had reason to believe were prominent members of the Triad Society, including two Chinese constables and an interpreter in the Police Court.Footnote 66 In a meeting, the police captain offered this by way of explanation:

As head of the Police I am satisfied that the persons herein named are dangerous to the peace and good order of the Colony…I have no reason to doubt that they are members of the Triad Society. I have personal knowledge of the two constables and the Magistracy Interpreter. Information about Police Constable Li Fan is contained in the report of the Board to enquire into the working of the Triad Society. I have known for some time that he was connected with the Society. I have no doubt about him.Footnote 67

Figure 2. Indian police and Chinese constables in the compound of the Central Police Station, Hollywood Road, 1906. Government Records Service, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, www.grs.gov.hk/en/index.html.

The police force could not effectively control the criminal element. There were several reasons for this. First, police officers recruited from overseasFootnote 68 had little knowledge of the Chinese community (which was rapidly expanding due to a continuous mass influx of migrants from mainland China), so they were unable to effectively detect crime or earn the support of the local community.Footnote 69 Second, both local and overseas police employees were very corrupt. For example, in 1897, a fifth of the entire police force on land, consisting of 14 Europeans, 38 Indians and 65 Chinese, were dismissed because they were convicted of accepting regular bribes from a gambling house.Footnote 70

The colonial government routinely banished any public servant who was a triad member but did not prevent its disciplinary forces being infiltrated by triad societies. From 1842 until the early 1970s, the government paid more attention to maintaining public order than controlling crime.Footnote 71 The corrupt nexus between triad societies and police officers thus became firmly established, enabling the triad-operated vice trade to flourish. Police corruption reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s. For example, an officer of the King Yee, a local triad group, told the second author that ‘my younger brother used to be a police officer working for the Serious Crime Bureau [in the 1960s]. With his protection, the King Yee managed to expand its territory to Tsim Sha Tsui.Footnote 72 He [the younger brother] worked for the Bureau during the daytime, while he worked for triad societies during the night.’Footnote 73 Another senior triad member emphasized the importance of establishing mutually beneficial relationships in their gambling dens:

During the 1960s, I followed CH [a senior triad member] to expand our gambling business to Mongkok.Footnote 74 In order to seek protection from police officers, we of course had to give money to them. In fact, many customers in our gambling dens were police officers…a police superintendent and his younger brother were regular customers [in our gambling dens], this was why we were able to create a very good relationship with police officers. The relationship is mutually beneficial: they truly enjoyed gambling while we were happy to make money. After gaining profits from the gambling business, we paid protection fees to police officers at different ranks…If we chose not to pay them, there was no way for us to run our business.Footnote 75

Interview data suggested that corrupt dealings between police officers and triad members were embedded in power-imbalanced relations, in which police officers were able to enrich triad members through abusing power while triad members were dependent on police officers to survive. By the 1970s, corruption in the Hong Kong police force reached its apogee. At that time, colonial police officers were not professional due to insufficient training and lack of proper supervision; most rank-and-file officers were from lower-class families and poorly educated. As triad members were embedded in lower-class communities and were neighbours or childhood friends of rank-and-file officers, it was not difficult for triad members to establish mutually beneficial networks with police officers. Moreover, some police officers joined triad societies during their teenage years and therefore had long-term connections with triad societies. The lack of professionalization and the embeddedness of rank-and-file police officers and triad members in lower-class communities gave rise to widespread police–triad symbiosis. This was used by corrupt police officers to collectively gain illicit profits, as Scott argued:

The police hierarchy was captured and subverted for the purpose of distributing corruptly-obtained money which was received by constables on the beat who then passed the proceeds on to more senior officers. The way in which ‘tea money’ was extracted from prostitutes, mini-bus and taxi drivers, and small businesses was highly organized…senior officers kept detailed records of which establishments had paid and which had not.Footnote 76

In 1973, there was a public outcry when Peter Godber, a chief superintendent accused of corruption, evaded prosecution by leaving the colony. The Godber scandal ‘led to street demonstrations with the war cry of “Fight Corruption, Catch Godber” and showed only too painfully how ingrained inside the Hong Kong police force had become the practice of requiring kickbacks’.Footnote 77 This made the colonial government realize that corruption challenged the legitimacy of colonial rule. In response, the government shifted its strategy to anti-corruption and crime control. It set up the ICACFootnote 78 to combat systemic corruption in the public sector, particularly the police–triad symbiosis.Footnote 79 In an interview, a triad member discussed the impact of the ICAC:

After the establishment of the ICAC, all triad members realized that there would be great uncertainties if they continued to earn income from illegal businesses and that they had to face a much higher risk of arrest. The booming businesses of prostitution, gambling and drugs experienced a sharp decline…many police friends with whom I used to work decided to cut all their contacts with triad members because they did not want to risk being dismissed…the ICAC encouraged police officers to adopt a much tougher attitude towards triad societies; such a change was also due to their desire to maintain a positive public image…a senior triad member, who openly claimed in front of police officers that he could do whatever he wanted after 12am (midnight), was soon arrested.Footnote 80

The ICAC and the gradual empowerment of law enforcement agencies rendered the traditional triad methods of ‘evading enforcement through bribing police officers and infiltrating the police’ ineffective. Triad societies were compelled to adopt new counter-measures in order to avoid punishment. Since the 1980s, their most important counter-measure has been the exploitation of new markets in mainland China.Footnote 81 As Lo and Kwok argued, ‘prosperity in China caused a process of mainlandization of triad activities because of an ever-increasing demand [for] licit and illicit services in Chinese communities’.Footnote 82 Mainlandization means that triad societies become more reliant on markets in mainland China, and they obtain business opportunities through establishing relationships with those in power on the mainland.Footnote 83 As a triad officer told the second author,

Sun Yee On was one of the first triad societies entering China's market. It managed to establish a great deal of business in the 1990s. Its success was attributed to the fact that senior members of Sun Yee On had built close ties with government officials. Many large-scale entertainment establishments (e.g. karaoke bars and nightclubs) in the city of Shenzhen were owned by Sun Yee On. Latecomers were not so lucky, however. The triad society I belonged to also invested in entertainment businesses in Shenzhen, but local police officers frequently raided our entertainment premises. My boss eventually decided to exit the business.Footnote 84

Confrontation

Despite the fact that interactions between the triads and the colonial government were usually of an enforcement–evasion nature, these low-competition relationships sometimes became high-competition through confrontation. This occurred on several occasions when triad societies were mobilized by the Chinese government to rebel against colonial rule and thus damage Hong Kong society. For example, the CantonFootnote 85 government mobilized the triads and other Hong Kong secret societies to lead the anti-French strike in September–October 1884.Footnote 86 The strike occurred as a response to the Sino-French War, a conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885, during which the colonial government ‘permitted French naval vessels to use Hong Kong's harbour for supplies and repairs’ and ‘made the situation worse by fining workers who refused to work for the French and prosecuting editors of local Chinese newspapers for publishing the anti-French proclamations from Chinese authorities’.Footnote 87 Dissatisfaction among workers and Chinese merchants led to the strike expanding to include the colonial government. Workers reluctant to strike were intimidated by triad members until they joined in. This strike prompted the rapid enactment of the ‘Peace Preservation Ordinance of 1884’, under which the colonial government banished any person who carried arms and harmed the peace and good order of the colony.

Triad societies also played a leading role in mobilizing workers to join the anti-imperialist general strike of 1925–26 (also known as the Canton–Hong Kong Strike).Footnote 88 The strike was sparked by an incident on 30 May 1925, when police officers under British command opened fire on Chinese anti-imperialist protesters in the International Settlement of Shanghai.Footnote 89 To facilitate a general strike against British imperial rule, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) employed their links with triad members who enjoyed an enormously powerful position among Hong Kong workers. Many leaders of triad societies were also leaders of labour unions and utilized their influence to mobilize workers. These leaders were also employed by CCP activists to generate an atmosphere of chaos and fear among the Hong Kong population.Footnote 90 After the worst of the strike was over, the colonial government formed the Emergency Unit and the Anti-Communist Squad to help it deal with strikes organized by CCP activists. In 1927, the Illegal Strike and Lockout Ordinance enabled the colonial government to criminalize any strikes that attempted to coerce the government.Footnote 91 All unions involved in the 1925–26 strike were banned by the colonial government, weakening the power of triad societies in labour unions.

Triad societies also confronted the colonial government during the 1956 riots (known as the Double Ten Riots). The riots, which started on 10 October and lasted for three days, were caused by tension between pro-Communist and pro-Nationalist factions in Hong Kong.Footnote 92 Triad societies were not key players in initiating the riots, but these societies, especially the 14K, led by Lieutenant-General Kot Siu Wong of the Nationalist Army, were ‘hastily mobilised and sent out to whip up the emotions of the crowd to cover looting activities of society members’.Footnote 93 The riots resulted in 60 deaths and 443 hospitalizations. The colonial government quickly passed emergency legislation and arrested over 10,000 14K members, 600 of whom were deported to Taiwan. The government also formed the Triad Societies Bureau to help the police collect intelligence on triad-related activities.Footnote 94

Integration

Some triad societies established a collaborative relationship with the Imperial Japanese government when Japanese troops occupied Hong Kong (1941–45).Footnote 95 During that period, local triad societies were divided into three camps. As Morgan argues, one camp consisting of triad societies working for the Nationalist Government of China decided to fight the Japanese, another camp chose to help the Japanese take over and govern Hong Kong and the third camp ‘was prepared to sit on the fence and join whichever side emerged victorious’.Footnote 96 ‘Integration’ is an appropriate term to describe the direct incorporation of pro-Japanese triad members into the Imperial Japanese government. The Japanese adopted the colonial policy of ‘using Chinese to rule Chinese’ (yi hua zhi hua) and therefore were ‘willing to use triad societies to assist them in their task of maintaining order’ and collect intelligence relating to anti-Japanese activities.Footnote 97 Triad societies were eager to collaborate with the Japanese because triad members were suddenly given control of ordinary citizens, and the Japanese ‘favoured and shared in the open organisation of prostitution, narcotics and gambling, which were the main sources of Triad revenue’.Footnote 98 Despite the fact that triad societies assisting the Japanese were accused by the public of ‘completely losing their conscience’, these triads benefited greatly from collaboration; it enabled them to expand their power by weakening their competitors (e.g. triad members who were against the Japanese) and control the vice trade and labour unions during and after the occupation.

Hong Kong triads in the post-colonial period (1997 to the present)

The establishment of the ICAC and the gradual empowerment of the police to tackle organized crime all but eradicated the police–triad alliance in Hong Kong. As Chu pointed out, the creation of the ICAC ‘gave the triads a severe blow as their illegal and criminal enterprises were no longer protected and tolerated by the Hong Kong police’.Footnote 99 Obligations of blood brotherhood and mutual aid were no longer important for triad societies; individual members capable of making money became new leaders responsible only to their independent units.Footnote 100 In the 1990s, researchers generated two competing hypotheses about the future of Hong Kong triads: first, transnationalization, suggesting that triad societies would establish branches in major cities all over the world and become increasingly globally significant; second, mainlandization, ‘the process of making Hong Kong triad societies more reliant on mainland China for financial gain through social networking with Chinese officials, enterprises and criminal syndicates and taking advantage of legitimate and illegitimate business opportunities resulting from China's economic growth and rising demand for goods and services’.Footnote 101 Triad societies encountered enormous obstacles when they transcended national boundaries.Footnote 102 For example, members’ criminal histories and low socio-economic status made it extremely difficult to migrate to western countries, and they were unable to compete with criminal groups in other countries because of language and cultural barriers and the lack of social networks.Footnote 103 The best option for triad societies was therefore mainland China.

China's central government adopted the ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement to ensure Hong Kong's long-term prosperity and stability. This guaranteed that Hong Kong's judicial, financial and political systems would remain unaltered until 2047. In order to address ‘the evolving contradictions in Hong Kong's post-handover period’, the Chinese government made great efforts not only to unite local political and business elites but also to unite ‘three types of “mass societies”: local federations, hometown associations and service-oriented NGOs’.Footnote 104 It included triad societies in its ‘united front’ work to co-opt and neutralize potential opposition before and after the handover. For example, Tao Siju, minister of public security, stated at a press conference in 1993: ‘As for organizations like the triads in Hong Kong, as long as these people are patriotic, as long as they are concerned with Hong Kong's prosperity and stability, we should unite with them.’Footnote 105

Since the handover, a patron–client relationship between the Chinese government and Hong Kong triads has been established: the triads have become patriotic and follow orders from mainland security authorities, and in return the Chinese government has given triad bosses business opportunities. As Michael Wai-man Chan, a Hong Kong actor and retired triad boss, explained, ‘All the existing triad groups in Hong Kong are patriotic and follow the country's orders…There is a public security ministry…they are not talking about cooperating with triads…No Hong Kong triad group dares to confront China's public security ministry…Whoever tries to do so will not be able to operate anymore.’Footnote 106

Chan also mentioned that in the post-colonial period the major change made by triad societies was that they regarded harmony, rather than conflict, as a golden rule.Footnote 107 In other words, triad members shifted their businesses from illegal to legal: some wealthy triad bosses operated gambling dens in Macau, where gambling was legal, while others invested in restaurants and tea houses. Although triad societies have become a declining urban criminal polity since 1997, this collaborative relationship with the Chinese government should not be ignored, because triad societies can employ covert immoral or illegal methods to help the government maintain prosperity and stability in Hong Kong.

The role of Hong Kong triads in repressing anti-government protests has increasingly come to public attention. During the Occupy Central Movement (see Figure 3), a large-scale pro-democracy movement that started on 28 September 2014 and lasted for 79 days, up to 200 gangsters from two main triad groups (Wo Shing Wo and Sun Yee On) were mobilized to discredit the movement.Footnote 108 As Lo noted, triad members disguised themselves ‘as not only blue-ribbon [government] supporters to beat up pro-democracy protesters [yellow-ribbon activists] but also [as] yellow-ribbon activists who plunged into police lines so that the police would be forced to clear up the roadblocks’.Footnote 109 Based on interviews with triad members, businesspeople and activists, Varese and Wong concluded that ‘Triad members mobilized because they were paid by powerful business interests connected to the Hong Kong government. We cannot rule out completely that these in turn were instructed by the Chinese government.’Footnote 110

Figure 3. The 2014 Occupy Central Movement (author's photo).

Interview data collected during the Occupy Central Movement also shows that, to facilitate police clearance of protest sites, triad members were paid for both ‘protecting’ and attacking protesters.Footnote 111 First, our interviewees (two triad members and a police officer) noted that some triad members were paid to protect the protesters.Footnote 112 Unfortunately, the interviewees refused to disclose who made these payments. Triad members stayed overnight in protest sites as ‘genuine protesters’ but acted aggressively and distributed money to their followers in front of journalists. This was to discredit the movement and cultivate a negative public perception of protesters.Footnote 113 Second, both a triad member and a senior triad member's wife mentioned that senior triad members were instructed to send their followers to attack protesters.Footnote 114 Attacking protesters created chaos in protest sites, provoking the police to conduct clearance operations.

Triad societies also helped the government attack pro-democracy protesters during the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill protests. These were a series of protest actions against the Hong Kong government's attempt to introduce the Fugitive Offenders (Amendment) Bill, which allowed extradition to jurisdictions like mainland China and Taiwan. On 21 and 22 July 2019, hundreds of people dressed in white T-shirts, including many triad members, attacked black-clad protesters and civilians who happened to be at the Yuen Long MTR station. The attack led to the hospitalization of 45 people. Police officers did not arrive until 35 minutes after the attack started and made no arrests.Footnote 115 The Yuen Long attack ‘raised public suspicion of police collusion with local gangs’ and was ‘a turning point of the 2019 anti-extradition protests in that it was at this moment that the police themselves became central targets of the movement as a whole’.Footnote 116

Our empirical data reveals that a majority of triad members in Hong Kong support the government and only a few triad members voluntarily joined or supported the social movement.Footnote 117 According to Kwok's unpublished ethnographic study of 18 triad members’ political attitudes, over 60 per cent claimed to be pro-government while only 18 per cent claimed to be pro-protesters.Footnote 118 There are several reasons for this. Triad members’ businesses in Hong Kong were threatened by the social instability caused by the social movement, for example during the prolonged occupation in Mongkok, a triad hotspot.Footnote 119 During the anti-extradition protests in 2019, the negative impact of protests on triad businesses was enormous. A series of protests significantly affected triad members’ minibus and taxi businesses, because many roads were blocked by protesters. Income generated from commercial rents and protection fees also decreased due to fewer local customers and tourists from the mainland. Most night-time entertainment premises were forced to close for lack of customers.Footnote 120 It was therefore sensible for triad members to support the government to end protests.

Social stability is crucial to mafia-type criminal groups. As Zhang and Chin suggest, a cosy operational environment and stable income streams are crucial to their sustainability.Footnote 121 From the triads’ perspective, social stability is more important than democracy, because they believe that only a stable society can lead to economic prosperity. Social change would only lead to unpredictability, threatening their vested interests. As a triad participant notes:

triads like us always hope for a stable society and economy. Only a stable society can secure our income and future development; this applies to both our legitimate and illegal businesses. Who knows what will happen if the political situation changes? Democracy only gives us an unpredictable future, so why bother to change? What if democracy will lead to chaos just like now: everyone is jobless and out of business…We agree with the government, only stability can bring us fortune.Footnote 122

Mainlandization is another reason for triads supporting the government. Mainlandization is a process of acculturation in Hong Kong that attempts to bring Hong Kongers into social, political and economic convergence with the mainland.Footnote 123 This strategy aims to cultivate economic reliance and political dependence on mainland China.Footnote 124 Many Hong Kongers have already benefited from mainland China's economic growth and are thus dependent on mainland China.Footnote 125 Triads, an integral part of Hong Kong, are no exception. For instance, prolonged protests reduced the number of mainland tourists,Footnote 126 which seriously affected triad businesses. In addition, many triad members, especially senior members, had invested in mainland China. If they supported the protests, their businesses in mainland China would be at risk. As a triad member noted:

As long as triad [members] have ‘businesses’ in Hong Kong and mainland China, I would say 99% of them are ‘blue’ [pro-government]. Like my Dai Lo [protector] and his senior triad brothers like XX [a former triad leader, name removed] and YY [another former triad leader, name removed], they are all ‘blue’. That's because their major source of customers is mainlanders and they also have legitimate businesses in mainland China. If they support those cockroaches [protesters], they will not be allowed to go to mainland China, and all of their businesses will be gone. Do you think that the Chinese government will allow them to earn their money [in the mainland] while tolerating their betrayal?Footnote 127

Both the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019 Anti-Extradition Movement are regarded by the government as part of the western-instigated Colour Revolution and a significant threat to China's sovereignty over Hong Kong.Footnote 128 Patriotic triads therefore have obligations to support the government, get involved in suppressing social protests and discredit the pro-democracy movement.

Conclusion

This article develops the concept of ‘urban criminal polity’ to explain how Hong Kong's political and social contexts affected the formation and development of criminal organizations and how criminal organizations interacted with politics over time. Criminal organizations as non-state polities generate a collective identity for their members and mobilize people and resources for shared objectives, such as self-protection and economic gain. The article uses the analytical framework of criminal politics (the relationship between organized crime and the state) to examine the historical and political origins of Hong Kong triads from two angles. First, it investigated the relationship between the colonial government's policy of ‘ruling the Chinese on the cheap’ and the rise of Hong Kong triads as self-protection and mutual-aid associations during the first hundred years of British rule. The government's unwillingness to provide social support to Chinese immigrants made the formation of triad-type organizations both attractive and inevitable.

Second, it examined the relationship between triad societies and politics under colonial rule and in the post-colonial era. Under British rule, interaction between the Hong Kong government and triad societies was characterized by enforcement–evasion arrangements: triad societies avoided police crackdowns by infiltrating the police and bribing police officers. On several occasions, triad societies were mobilized by Chinese organizations, such as the Nationalist Party and the CCP, to confront the colonial government. The government responded by empowering its anti-crime agencies and arresting and deporting triad members. The establishment of the ICAC in 1974 rendered traditional ways of avoiding law enforcement ineffective and triad societies avoided arrest by exploiting China's new markets.

Since the handover, an alliance (or patron–client relationship) has been established between the government and triad societies. In order to survive, triad societies have had to become patriotic, working for the Beijing and Hong Kong governments to maintain the stability and prosperity of Hong Kong. In return, the Chinese government offers protection and business opportunities. The involvement of triad gangsters in repressing anti-government protests, such as Occupy Central and the Anti-Extradition Movement, generated public suspicion of government collusion with triad gangsters, which has led to declining regime legitimacy and increasing public anger towards the police. Nevertheless, interactions between the government and patriotic triads are embedded in a power-imbalanced relationship. Triad societies have never been granted political power by the government and are therefore not able to challenge the state. This is not what happens in long-standing mafia organizations in other countries or regions. For instance, mafia groups in Italy (e.g. Ndrangheta families and Cosa Nostra) are able to influence electoral results and get their favoured politicians elected,Footnote 129 which tends to even out the balance of power between these mafia groups and politicians.

The historical and political investigation of Hong Kong triads contributes to the study of the relationship between organized crime and the state while also offering an important perspective on Hong Kong society. Now that Hong Kong is becoming a battlefield between authoritarian China and democratic states, Hong Kong studies and related topics (e.g. triad societies) will doubtless expand into a key field in area studies in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Baris Caily, Hilary Wright and Jingyi Wang for their valuable comments on this article. The Referees' suggestions helped us improve the article. All errors remain our own.