Introduction

This is Irish Nannie: out o’ jail again an’ lookin’ for throuble; let them send along their Baton Men, Nannie's got a pair o'mits that'll give them gib.Footnote 1

Eschewed by Irish audiences in part for its brevity but also for the perceived vulgarity of its content and main protagonist, Nannie's Night Out (1924) was consequently one of Seán O'Casey's lesser-known plays.Footnote 2 Critics judged the ‘comedy’ harshly, as it formed part of the continuum of his well-received ‘Dublin trilogy’: The Shadow of a Gunman (1923), Juno and the Paycock (1924) and The Plough and the Stars (1926).Footnote 3 Set in the Dublin tenements, Nannie existed in the margins of working-class life and often fell through the cracks of official documentation. As such she existed as a trope of othered women who were both intrinsic to the city's fabric and rejected in equal measure. During the course of the one-act play, we learn that she was recently released ‘out o’ the “Joy”’ (Mountjoy Prison).Footnote 4 Behind the drunken exterior lies a 30-year-old single mother, living precariously on the streets when not incarcerated. Common to those caught in the bind of arrest and release, her kinship supports appear frayed, and her life was marred by ill-health and misfortune: her son suffers from a spinal disease, and for two years she maintained her father, a dock worker who was not adequately compensated when he suffered life-altering injuries in a crane accident. An alcoholic, it is implied that Nannie is also a prostitute. The original play ends abruptly with her death, and in a subsequent version she is taken away by the police after smashing shop windows. In this play, O'Casey presents a vignette of the struggles of the most disadvantaged women in Dublin tenement life – using humour to highlight enduring social problems of poverty, alcoholism, reduced life expectancy and power imbalances.

Part of the aim of this work is to locate the plight of single and poor women like those presented in the play. It focuses on the official sources that record the lives and deaths of young adults (15–34 inclusive) in one north Dublin ward, North City 1 East (NC1E), in 1901 and 1911. NC1E was where O'Casey was from and where Dublin's red light district ‘Monto’ (derived from Montgomery Street) was located. Recognized as one of Europe's largest unregulated, commercial sex districts in the late Victorian era, brothels operated openly in Monto, and some contained shebeens selling alcohol without a licence.Footnote 5 Dublin city's high death rate led the Local Government Board to appoint a committee to inquire into the state of public health in 1900. Among its findings was that in the preceding decade the death rate was ‘considerably in excess’ of the 33 largest towns in England. In all age cohorts, Dublin city's mortality rates were higher than London's, but in the 15–34 age range the rate was double, and a matter of grave concern.Footnote 6 High infant and child mortality was a common feature of urban life, but cause of death data for young adults has not been examined despite contemporary concerns for ‘Irish Nannie's’ age cohort.

Data from death registrations and census returns are a treasure trove for the social history of poverty, class and medical history. A closer reading not only reveals gender and class-based assumptions in the acts of reporting, but also the levels of discretion afforded to the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), particularly when dealing with those on the margins, such as prostitutes. Judith Walkowitz has been critical of the way in which Olwen Hufton's makeshift economy framework has been applied by modern studies of prostitution. She notes its ‘conceptual limitations’ in revealing intimate lives, but concedes it is symptomatic of the paucity of primary sources.Footnote 7 Julia Laite found in her research on sex workers in London that their lived experience was difficult to uncover; Dublin is no different.Footnote 8 Thus, another aim of this work is to mine official sources further to locate that community in wider socio-economic contexts using digital humanities tools.

Methodologically, we draw on a digital humanities framework similar to those employed by the London Lives project.Footnote 9 The urban masses are generally difficult to track, but as this article shows, by linking and mapping the granular data of individual entries, more details of their community networks can be revealed and distinctions can be made between the poor, the desperate and the destitute. We devised an application to create datasets from civil registration of death records and used the outputs in tandem with census returns to re-examine occupations and household structures.Footnote 10 When these data were mapped in historical Geographical Information Systems (hGIS) it permitted us to view the city in new ways and helped to find those who were engaged in sex work on a more permanent footing.

Jeffery Weeks cites class differences as a key aspect of ‘sexual respectability’ which was reflected in statute and ‘expressed the aspirations and lives of the middle class’.Footnote 11 This research heeds the cautions of earlier scholarship and contends that prostitution as an occupational descriptor is an unstable entity, particularly in Dublin, where Westminster statutes were interpreted and adapted for a colonial context.Footnote 12 In that interpretative space, police discretion dictated when and if labels were applied, and if prosecutions would follow.Footnote 13 Our study of NC1E uncovers the financial vulnerability of single young women in Dublin city and how their social positioning was reframed by police discretion.

In an economy that has been pejoratively described as being heavily dependent on ‘beer and biscuits’, few households had income security.Footnote 14 A small proportion of working-class Dublin families fit the ‘male breadwinner’ model, where incomes afforded an ‘idle’ wife and school-going children.Footnote 15 Reliance on casual earnings from ‘women's work’ is a sensitive indicator of household-level economic buoyancy, and indicative of other problems in the labour market. By analysing and mapping various data, we show that not only is it possible to identify and decode the levels of discretion at play, an impression of the shadow economy can emerge. Many women kept lodgers or were ‘room-keepers’ and were legitimately returned as such in official sources. It was a casually applied label and, as this research shows, at times it was used euphemistically and as a cover for brothels. NC1E was the locus of commercial sex work and its reform and the boundaries between both worlds were fluid. Women used the Magdalen Asylum as a reprieve from the elements and as a way of keeping a low profile with the DMP. When women tired of the conditions, the world outside its front door offered ample opportunity to resume sex work.Footnote 16 This opened up the prospects of arrest for soliciting, accusations of larceny and general public disorder offences like drunkenness, and profane language usage.Footnote 17

Feminist historians from Walkowitz to Julia Laite have emphasized that the absence of a legal definition of prostitution is problematic.Footnote 18 In Ireland, the prostitution narrative was complicated by association with the British Imperial project. Outside of Unionist strongholds of Ulster, Irishmen who served as soldiers and sailors were increasingly seen as members of the occupying British crown forces and were othered in Irish society. As Joseph Valente has argued, they were caught in a ‘double bind’ of being both subjects and agents of colonialism.Footnote 19 Prostitution was othered by association; the Contagious Diseases Acts (1864–69) applied only to the garrisons of The Curragh (and some adjoining townlands), Cork (the borough) and Queenstown (town limits).Footnote 20 Despite problematic social-class biases, the acts were repealed in 1886 in a significant coup for women's rights and bodily autonomy. Other than those listed as patients of the Westmoreland Lock Hospital, thereafter the prevalence of venereal disease was not officially collated, because there was no regulatory instrument or oversight of sex workers.

Under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885, crimes associated with prostitution, such as brothel keeping and soliciting, became misdemeanours carrying fines or sentences of under two years.Footnote 21 Whether women were documented or prosecuted for crimes adjacent to prostitution hinged on their interpersonal relations with one another and the DMP. It was an entirely subjective process, which means that historians have to read between the lines and across several datasets to find them. Section 11 of the 1885 Act, or the Labouchere Amendment, referred specifically to male homosexual activity as a matter of ‘gross indecency’. Scant attention was paid by the police or moral reformers to male prostitutes despite or perhaps because of the ‘Dublin Castle’ scandal of 1884, involving high-ranking agents of British Administration in Ireland.Footnote 22 Male prostitution is harder to track than female. But if patterns uncovered in the 1884 scandal are indicative of how it operated, it was a well-kept if open secret.

Throughout this article, the problems with the ontological order of official data is emphasized. In particular, the culminative effects of the legacy of the patriarchal ‘breadwinner’ mentality that governed the collation of the 1891 census, the limitations of classification and the discretion afforded to DMP officers served to underestimate the contribution of poorer women and children to household economies. That women's work was devalued by design is a well-established fact, but the net result was that it hid other socio-economic problems that tended to locate in areas of systemic disadvantage. It is within the ‘economy of makeshifts’ that evidence of commercial sex work finds expression.

Focusing on the two types of official ‘big data’, this study provides an overview of cause of death among young adult cohorts and adopts a combination of case-study and prosopographical approaches to trace the lives of the ‘unfortunate’ classes. The next section provides an overview of the housing conditions in NC1E to contextualize the data, after which the main findings from these data and the methods employed to visualize them in hGIS are presented. The penultimate section discusses cause of death, to situate the concluding case-study on prostitution and its occupational hazards.

Housing

With the redrawing of polities and the shift of power to Westminster following the enactment of the Act of Union in 1801, Dublin's positioning as the second city of the empire was lost by the 1830s.Footnote 23 Socio-economic decline was accelerated by the movement of elite families from the city centre to London, and the flight to the more healthful suburbs, particularly in the post-Famine era. Even after the extension to the city boundary came into fruition in 1901, the borough comprised 7,911 statute acres. Although a significant increase on the previous 3,733 acres, Dublin remained a small city.Footnote 24 The river Liffey provided the midline boundary between the north and south city wards shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Dublin, North and South Wards, Dublin Metropolitan Police stations shown as points, c. 1900. Map based on information derived from the Dublin Metropolitan Police Committee of Inquiry 1883 [C.3576 C.3576-I], p. 25, and Statistical Tables of the Dublin Metropolitan Police for the Year 1901 [Cd. 1166], p. 33, drawn using OSi historic 25-inch basemap © Tailte Éireann/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 001023.

Figure 2. Extract from ‘Map of the city of Dublin and its environs’ (c. 1910) showing North Dock Ward, Mountjoy Ward, railways, tramways and the Royal Canal.

Source: https://collections.library.utoronto.ca/view/mdl:G5784_D7_F7_10_190---191--.

By 1901, NC1E included parts of three district electoral divisions (Inns Quay, Mountjoy and North Dock) and the entire ward was located in the DMP C (Rotunda) Division.Footnote 25 Wards and DMP divisions formed the basis for civil registration and census data collection respectively. From 1864, relatives or institutions were supposed to register births and deaths with the local registrar, who was a dispensary doctor. The ward included two dispensary districts and associated district medical officers of health. The main DMP stations were Summerhill and Store Street, and Mountjoy Prison was adjacent (Figure 1). The ward was intersected by the Royal Canal and the northbound tramlines, while North Wall and Amiens Street railway stations were busy commercial and passenger terminals respectively (Figure 2). Dublin's North Docks dominated the eastern part of NC1E, with its steamship companies, boat maintenance, cattle markets, timber and coal yards, stores and goods sheds. Cranes, lift bridges and turntables were part of the urban fabric of this area and, together with transportation occupations, they increased the level of occupational hazard in predominantly temporary jobs.Footnote 26 O'Casey personified this occupational risk through Irish Nannie's father, whose workplace injuries disabled him. While some locations such as Nottingham Street attracted middle-class merchants and brokers, most inhabitants of NC1E were working class. The western area of NC1E included Mabbot Street, Lower Tyrone Street, Cumberland Street, Birmingham Street and Gloucester Street, notable for their tenements and highly concentrated population.

Employers like Guinness’ Brewery and Jacob's (biscuit) factory provided steady ‘breadwinner’ incomes. But even those employees’ wives kept occasional lodgers to make ends meet until children reached working age.Footnote 27 For families with unsteady incomes, life was precarious and among the inevitable consequences was inferior housing offering rentals at the lowest costs. Cash incomes were spent within a few days, and most households resorted to pawnbrokers on a weekly basis.Footnote 28 Most families pooled their incomes, and child earnings were integral to household survival. Irrespective of the compulsory education age of 14 following the Education (Ireland) Act 1892, the 1902 Commission on Street Trading found 214 boys and 32 girls aged under 14 engaged in paid employment as messengers and in hawking newspapers, fish and fruit.Footnote 29 Girls, predominantly but not exclusively, aged under 14 were undoubtedly tasked with unpaid childcare of younger siblings to enable parents to engage in the workforce.Footnote 30 In the Dublin circuit, education inspectors cited reasons such as poverty and sickness for rates of absenteeism, both of which were enduring features of family life in NC1E.Footnote 31

Architecturally, Dublin's northside was dominated by the townhouses of the Gardiner estate, which was constructed in the late eighteenth century and housed some of the city's wealthiest denizens. Jacinta Prunty observes that during the nineteenth century, much of the Gardiner estate was sold to individual bidders on a piecemeal basis.Footnote 32 Unscrupulous landlords, seeking to maximize profits, subdivided these buildings which became overcrowded dwellings for multiple low-status families. The transition from Georgian townhouse to tenement was complete by 1900.

Apart from subdivided townhouses, rows of workers’ cottages were built on NC1E's smaller streets like Oriel and Emerald Street from the 1840s infilling the spaces between arterial roads such as Sherriff Street. By the late 1880s, the ‘semi-philanthropic’ Dublin Artisans' Dwellings Company (DADC) had constructed rows of workers’ cottages in the area around Seville Place,Footnote 33 but it was not enough to change the overall character of housing. Rental agreements with DADC were generally considered expensive. Appealing to what Murray Fraser described as ‘the elite of the working class’, they were beyond the means of ordinary households.Footnote 34

Exacerbating the sorry state of housing stock was a chronic shortage and relatively high costs: one-room flats in Dublin commanded rent of 3s per week, the same as a three-room house in Belfast.Footnote 35 This gave rise to a range of informal subletting practices. Socially, NC1E contained a highly mobile population of working-class poor who lived predominantly in overcrowded and unsafe tenements. Their mobility was in part prompted by the ad hoc nature of rental agreements, which were predominantly oral. Tenement owners rarely engaged in direct associations with tenants; instead, ‘house farmers’ divided properties into rooms.Footnote 36 For those who could not afford to set up their own households, several lodging and boarding houses of varying standards were in operation.Footnote 37 Single people were often internal migrants and even for those with steady employment, survival was difficult. They rented living space as lodgers or boarders, and if they fell on hard times they could not expect support from non-relatives.

A detailed analysis of death records along with census data suggests a blurred distinction between ‘housekeeper’ and ‘roomkeeper’. Housekeeper can mean women who performed unpaid domestic duties in their own or the homes of others, and roomkeeper indicates women who may have earned a living by keeping lodgers either in their own homes or in sublet rooms. ‘Roomkeeper’ was mentioned repeatedly in the 1878 Public Health Act, but not defined. The act permitted local dictates to assist in its operation, which caused further complications.Footnote 38 According to Dublin Corporation by-laws, a tenement was defined ‘as a house or part of a house…let in lodgings or occupied by members of more than one family’. Roomkeepers, as distinct from ‘lodging house proprietors’, were included in the provisions and defined as people who rented rooms and sublet them for occupational purposes.Footnote 39 Sir Charles Cameron described them as ‘house jobbers’, whom he believed were to blame for rental market fragmentation and price inflation.Footnote 40 Under the by-laws, sanitary officers were entitled to inspect housing and roomkeepers were obliged to permit them access.Footnote 41

Experienced medical officers like Dr Thomas Donnelly, 14 Rutland Square, and Dr John Crinion, 58 Amiens Street, worked together with the local authority sub-sanitary inspectors to try to take dilapidated housing out of usage. Militating against them was the arduous process of getting housing condemned. For example, in the third quarter of 1901 only 25 of 195 houses inspected were condemned and just one building, 19 Gloucester Street Lower. On census night it housed 13 adults.Footnote 42 Even after houses were condemned, squatters remained and the destitute poor continued to occupy them.Footnote 43 It was in this ad hoc rental market that commercial sex work proliferated out of public view and evaded prosecution; evidence of this use will be discussed in later sections.

Data and methodology

According to the Annual Reports of the Registrar General (ARRG) for 1901, NC1E contained 28,201 people, living on 674 statute acres, who registered 526 deaths and 694 births that year.Footnote 44 By 1911, the population had increased to 29,525 people, but slight decreases are noted in the number of births and deaths (470 and 646, respectively).Footnote 45 The nominal index data available on irishgenealogy.ie for deaths occurring in 1901 and 1911 were extracted to enumerate all registered deaths in this ward to examine causal factors. Masters’ level students transcribed the records into an application co-created by the project team.Footnote 46 Sorting the final dataset into quarters permitted the inclusion or exclusion of late registrations within their correct calendar year. There was a discrepancy of 10 entries per year for this district when indexed electronic data of the individual level returns were cross-referenced with the ARRG.

Both datasets (General Register Office (GRO)/NC1E/1901, GRO/NC1E/1911) of registered deaths were cleaned prior to analysis. They were sorted by primary cause of death and categorized at a high level in accordance with the prevailing nosology, which prioritized zymotic diseases, diseases of systems and organs and those of various seats.Footnote 47 Ontological limitations continue to beleaguer historical epidemiology and whether deaths are ‘of’ or ‘with’ a particular disease is a perennial problem. For example, William Duke, a railway guard, died in 1911 aged 23. The primary cause was exhaustion, but the secondary causes were pneumonia and phthisis.Footnote 48 We remained faithful to the record and counted this as exhaustion, but it means underlying conditions may have been under-represented in the aggregated ARRG.

Cause of death data for those who died aged 15–34 in NC1E in 1901 were entered into a spreadsheet with separate fields for names, surnames, house numbers and streets. Street names were standardized; as an extensive programme of renaming occurred post-Independence in 1922, a range of sources were used to match historical street names to their current identities.Footnote 49 The geographic co-ordinates of their centre-points were identified using open data from logainm.ie (an Irish government platform) for extant streets. The information was then uploaded to ArcGIS online and place of death data was represented by points. Pop-ups were configured on these points to include further information extracted from death records and links to the 1901 census.

With this approach, it was possible to discern a hierarchy of occupations and associated living conditions. Families occupying the lowest standards of housing were often reliant on supplementary income from boarders. This led to overcrowding and greater risks with respect to contagious diseases. Given the shortage of housing and the tendency towards overcrowding, single women as sole occupant households naturally emerged as unusual.

Cause of death, life stage, occupation and gender

Hyper-localized studies are often criticized as being unrepresentative of the whole. But detailed analyses of areas like Monto can cast light on alterity and how the economy of makeshifts affected life expectancy. Dublin had a comprehensive system of dispensaries and hospital care, and data for Dublin North Superintendent Registrar's District shows that 64 per cent of deaths occurred in a domestic setting.Footnote 50 All deaths registered in NC1E in 1901 took place at home, because the nearest workhouses, hospitals and asylums were located elsewhere. Of these registered domestic deaths, 90 per cent were certified by a local physician, 7 per cent were uncertified and 3 per cent related to inquests.

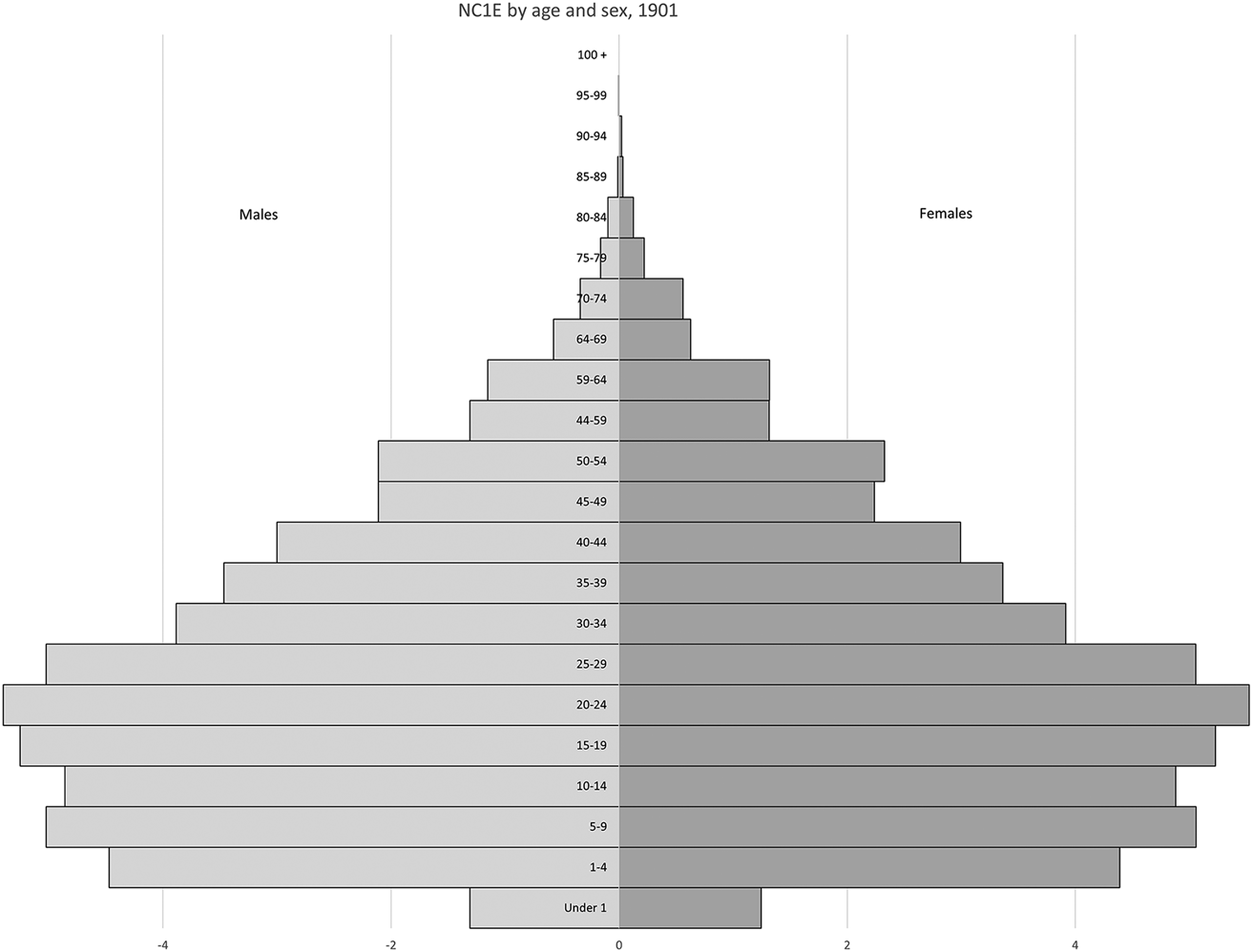

In 1901, the total population of NC1E was 28,201 individuals. This was a young population with limited life expectancy (Figure 3). Figure 4 indicates high infant and child mortality rates in NC1E with over 30 per cent of deaths in 1901 and 1911 relating to infants. The death rate declined significantly after the age of 5, so the number of young adults who died in the study years of 1901 and 1911 is relatively low (62 in 1901; 42 in 1911). In 1901, 5,516 males and 5,563 females aged 15 and under 35 were resident in NC1E (total 11,079); in 1911, similar figures of 5,413 females and 5,641 males (total 11,054) were returned.Footnote 51

Figure 3. Population of NC1E by age and sex, 1901

Source: Census of Ireland 1901, Part 1, Vol. 1, Province of Leinster (London, 1901), Table XV, Ages of persons in Poor Law Unions and Dispensary Districts in the city or county borough of Dublin, 31 March 1901, p. 13.

Figure 4. Age at death as a percentage of total deaths in NC1E, 1901 and 1911.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1901 and 1911.

Figure 5 breaks down cause of death data for the 15–34 cohort. Pulmonary tuberculosis was rampant, representing 86 per cent of all respiratory deaths (37 people) as compared to 56 per cent of all deaths in NC1E in 1901. This doubling coincides with what was considered a peak in Irish mortality from the disease, but it could equally reflect a more precise cause of death identification. Despite an increase in population, in 1911 a lower number of deaths (42) was reported and 45 per cent were from respiratory diseases. Among the 14 deaths from pulmonary tuberculosis was Cornelius Twohig, a 32-year-old accountant. Born in Cork, and married to a solicitor's daughter, he was a member of the professional classes living in Nottingham Street.Footnote 52 Infectious droplet diseases did not differentiate between social class, but mapping data allows patterns to be discerned. Individual deaths from Figure 4 were plotted as point data into a GIS and a heatmap was created for each year (Figures 6 and 7). In 1901, the density of deaths from respiratory diseases focused on three main areas: Sheriff Street and Mayor Street to the south of Figure 6, the Ballybough Road area to the north and a cluster of streets, namely Gloucester, Mabbot and Tyrone Streets, to the west. By 1911, the greatest density of respiratory deaths was focused on Ballybough Road, an area notorious for its poor tenement buildings.

Figure 5. Cause of death – men and women aged 15–34, NC1E, 1901 and 1911.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1901 and 1911.

Figure 6. Heatmap of deaths from respiratory disease, 15–34 age cohort, 1901.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1901. Map created using OSi historic 25-inch basemap © Tailte Éireann/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 001023.

Figure 7. Heatmap of deaths from respiratory disease, 15–34 age cohort, 1911.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1911. Map created using OSi historic 25-inch basemap © Tailte Éireann/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 001023.

Occupation

Where data from death records can be matched with census returns, the occupational information can provide insights into the socio-economic status of individuals and households. Many of the unskilled workers who lived in the NC1E community were precariously employed. Cross-referencing deaths occurring in 1901 and 1911 with census records from the same years clearly shows the temporary nature of this community's work. Despite the temporal proximity, it can be hard to match addresses in both datasets because people moved around so much. Descriptions of individual employment history often indicate a highly volatile labour market: 17-year-old Patrick Doherty, who died after suffering from phthisis for one year and influenza for three weeks, was unemployed at the time of the census,Footnote 53 but described as a labourer in his death record four months later.Footnote 54 Labourer was an umbrella term for the unskilled, and it is unlikely he was working in his final stage of illness. But his family along with the registrar noted his ‘usual’ occupation to articulate respectability in death.

The 1901 census divided occupations into six main classes: professional, domestic, commercial, agricultural, industrial and indefinite/non-productive.Footnote 55 Death data for the 15–34 cohort in NC1E in both 1901 and 1911 was extracted and organized into these classes (Table 1). A high proportion of deaths occurred among those of indefinite employment (27 per cent in 1901; 38 per cent in 1911). Most employed people came from the industrial class, both in 1901 (40 per cent) and 1911 (29 per cent), which included lodging house keepers, printworkers, factory girls, shop assistants and general labourers. The next largest category was the commercial class which lay at 27 per cent in 1901 and 19 per cent in 1911. This included office workers and those involved in the lower end of the transportation of goods, such as porters, drivers and sailors.

Table 1. Breakdown of NC1E death data of 15–34 age cohort by occupational class, 1901 and 1911

Source: Analysis of 1901 and 1911 census of Ireland, occupational tables.

The indefinite/non-productive category allowed enumerators much discretion and this is where the makeshift economy can be found. Married women with no occupation were included in this category, as well as children. All married women who died in NC1E in 1901 were described either in terms of their husband's occupation (‘wife of civil servant’) or as ‘housekeeper’, so were classified under indefinite/non-productive (class VI). Of the 11 married women who died in NC1E in 1911, all but 3 were described as ‘housekeeper’, the others being a ‘roomkeeper’, ‘wife of brushmaker’ and ‘tailoress’. Though sub-categories are included in census reports, the remaining data are still problematic and benefit from further breakdown. For example, keepers of board and lodging houses are categorized as Class V (industrial) but the occupational overlap with roomkeeping is undeniable (we include roomkeeping in Class V). Given its association with wives of men with steady incomes, housekeeping is more appropriately placed into indefinite Class VI. The census enumerators, who were members of the DMP, acted on their own discretion, and even a cursory feminist approach to the data shows it was skewed in favour of the male breadwinner model.Footnote 56 Household work, the care and keeping of lodgers (apart from roomkeepers) and part-time work were generally under-represented. Equally, the term ‘launderer/laundress’ is problematic, indicating both the self-employed and women within reform systems like Catherine Boothman and Anne Josephine Dunne who both died at the Magdalen Asylum on Gloucester Road in 1911.Footnote 57 Catherine was resident at the same Magdalen Asylum in 1901, aged 22. While she may not have been an inmate for the entire ten-year period, her reliance on that institution has a resonance of being from the ‘unfortunate’ class.Footnote 58

In 1901, 120 women aged between 15 and 93 died in NC1E, 14 were described in relation to their husbands’ occupation. Of the remaining 106 women, 48 per cent were described as ‘housekeeper’, 16 per cent as ‘roomkeeper’ and 11 per cent as ‘lady’. Most of the latter group died at St Joseph's, Portland Row, an asylum run by a Catholic religious order of women for ‘aged single females of unblemished character’.Footnote 59 In contrast with the 109 women residing in St Joseph's in 1901, 79 were enumerated in the nearby St Mary's Penitent's Retreat on 95 Lower Gloucester Street, as the Magdalen Asylum was then known.Footnote 60 Bridget Campion illustrates the fluidity between Monto and St Mary's. She was resident at St Mary's on census night, but a prostitute from 7 Faithful Place according to her GRO death certification in November 1901.Footnote 61 In 1911, 133 women from NC1E aged between 15 and 92 died; 41 per cent were described as ‘housekeeper’ and 19 per cent as ‘roomkeeper’. The proportion described as ‘lady’ remained stable at 11 per cent, 135 women were resident in St Mary's.Footnote 62 Kathleen Walsh who accidentally drowned after falling into the river Liffey was described as a ‘brushmaker's wife’.Footnote 63

Figure 8 shows all deaths within the 15–34 cohorts in NC1E in 1901. In line with the census reports, these are subdivided into five-year segments (15–19, 20–4, 25–9 and 30–4), each represented by a different shaped point. This enables the relationship between life stage, skills, occupational opportunities and progression through the labour market to be traced. Young people were expected to contribute to the household economy through paid and unpaid labour. In 1901, 15-year-old Mary Hennessy moved from Dundalk to live in the Upper Buckingham Street tenements. She had no occupation according to the 1901 census, but because both parents worked (father as a bell fitter and mother as a dressmaker) and had no family nearby, it is likely that Mary cared for her three younger siblings. She was found drowned in the Royal Canal. Although her inquest verdict was open, her father in evidence at the coroner's court stated his belief that it was a suicide case owing to melancholia surrounding her menstrual cycle.Footnote 64

Figure 8. Deaths in NC1E, 1901, by age cohort.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1901. Map created using OSi historic 25-inch basemap © Tailte Éireann/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 001023.

The progression from unpaid to paid employment is reflected in the use of ‘boy’, ‘girl’ and ‘apprentice’ in occupational titles of the 15–19 cohort. As a compositor's apprentice, 16-year-old Walter Carraher, who died from acute pulmonary tuberculosis, was learning typesetting skills in the printworks. In 1901, only one of the six NC1E women who died aged 25–9 years was married, reflecting the countrywide trend of later marriage age. Margaret Mansfield's husband was a civil servant and their household adhered to the middle-class breadwinner model where a wife's role was associated with domestic duties.Footnote 65 By contrast, all single women in the 25–9 cohort had an occupation, whether dressmaker, housekeeper, post office assistant, prostitute or shop assistant. In 1901, all but one of the 30–4 cohort were married or widowed. Four were described in relation to their husbands’ work: coach painter, insurance agent, policeman and carpenter. This suggests they did not work full time; their husbands would have been considered skilled and artisanal workers straddling the upper working and lower middle class.

‘Respectable’ single and Dublin-born women usually lived with their families while the linked data for NC1E shows prostitutes were more likely to be living as lodgers or boarders. In her analysis of Nannie's Night Out, José Lanters notes that absence of a ‘paternal or marital surname’ indicated Nannie's loose kinship bonds.Footnote 66 Co-residence with family of origin not only made financial sense, it offered young women respectability and a protective structure in accordance with prevailing morals: Anne Martin, a shop assistant, lived with her dairy proprietor father, her mother and three siblings;Footnote 67 Christina McDermott lived with her widowed father, sister and aunt; and Alice Gorman, a widowed dressmaker, lived with her widowed mother.Footnote 68

In the absence of immediate family, wider kinship bonds were important. Louisa Colhoun, a 29-year-old ‘roomkeeper’, died of pulmonary tuberculosis and a miscarriage at five months at her residence in Ballybough Road in February 1911. By April 1911, her mother, widower and three children had formed a household and were living as boarders in the home of a naturalist and his family, a distant relative of her mother's.Footnote 69 Women who resided in St Joseph's or the Magdalen Asylum were invariably without the comfort of relatives. Sex work was well beyond the realms of respectability for the middle classes, but in lower socio-economic groups, where it was very easy to slip down the ranks, judgment was reserved.

Prostitution in NC1E

Irish Nannie. ‘Two months I done…assault an’ batthery on a Polisman…me an’ him had a sthruggle…

Mrs Pender. Wasn't that th’ second time you were in Mountjoy Nannie?

Irish Nannie. Second time me neck! Th’ hundhred an’ second time…

Irish Nannie [coughing, sits down]. I'm dying on my feet…th’ spunk has me nearly done for…Th’ prison doctor told me th’ oul heart was crocked, an’ that I'd dhrop any minute…

Mrs Pender. She's full up of methylated spirits again. She'll start smashing windows any second.Footnote 70

Police were central to the labelling of women in lower socio-economic groups primarily in life but also in death. Women do not self-identify in the 1901 or the 1911 census as prostitutes, rather they are described as such by DMP officers, who were also instrumental in how they were categorized in the petty courts and the carceral system. DMP surveillance maintained a careful balance of policing by consent and good community relations.Footnote 71 It is unclear if police played a direct part in the city's commercial sex industry, as there is little evidence of extortion or bribery but complicity is implied as several prostitutes were allowed, as Walkovitz found, ‘to ply their trade as long as they were not public nuisances’.Footnote 72 Like the fictionalized ‘Irish Nannie’, those who fell foul of local DMP officers were caught in the arrest and release cycle, as the case of Henrietta Tully illustrates (Table 2).

Table 2. Henrietta Tully's imprisonment in Grangegorman and Mountjoy

Sources: National Archives of Ireland (NAI)/PRIS/1/9/36, General register, Grangegorman Female Prison (1892), no. 194; NAI/PRIS/1/9/39, General register, Grangegorman Female Prison (1896), no. 3,710 (1897) nos. 160, 672, 1695, 1948, 3363; NAI/PRIS/1/11/33, General register of female prisoners, Mountjoy, Dublin (1899), nos. 861, 2995; NAI/PRIS/1/44/01, General register of female prisoners, Mountjoy, Dublin (1899–1900), nos. 2,400, 3022, 5019, 5,425; NAI/PRIS/1/44/02, General register of female prisoners, Mountjoy, Dublin (1901–02), nos. 1,925, 3061, 5,182, 5438.

Were the manuscript census returns to be taken at face value, then, all but one (Maggie Maynes, the sole occupant and head of a household in County Antrim) of the 211 women returned as prostitutes in 1901, and all 160 returned in 1911, were incarcerated in prisons or asylums on census night.Footnote 73 Maria Luddy offers advice on euphemistic language use and argues that sex workers were betrayed by location.Footnote 74 She speculates that Catherine Gordon, listed in the 1901 census as a ‘housekeeper’ and living at 4 Elliot Place with three other housekeepers, was a prostitute.Footnote 75 Since the publication of Luddy's book, the manuscript census returns have been digitized and placed online, which allows for greater interrogation and cross-referencing with prison, workhouse and other datasets.

Key identifiers of prostitution in the census are households with female heads or sole occupancy, coupled with street name, age and certain occupations. Data from the census was sorted by relationship to head, sex and marital status in order to identify single women who were household heads. Sole occupants and women living with non-relatives (particularly other single women) were included in the analysis. Figure 9 shows the locations on Purdon Street of 18 households (in eight houses) headed by single women (their sex was omitted from the census, but all names were female). The figure includes women described as housekeepers or descriptors like ‘proprietor’ used to describe Lilly/Lillie O'Connor of 7.4 Purdon Street. Few single-occupancy male households exist in NC1E, suggesting that male prostitutes were located elsewhere in Dublin.

Figure 9. Households in Purdon Street tenements headed by single women, 1901.

Source: Analysis of 1901 census of Ireland.

When enumerating the census, some DMP officers offered female prostitutes a veneer of respectability by using known occupational euphemisms: Jane Halpin, and her five ‘lodgers’, were all described as ‘unfortunate’.Footnote 76 Two of her fellow housemates, Limerick-born Nellie Mitchell and Nellie Maher, are definitely labelled ‘prostitutes’ in the prison registers.Footnote 77 Equally implausible was the descriptor of ‘scholar’ for Emily Mack and the five other women aged between 23 and 32 she lodged with at 15 Elliott Place.Footnote 78

GRO returns sometimes offer ways of identifying women classified by the DMP as prostitutes, pinpointing their addresses so their networks can be mapped. They can be systematically matched with coronial court, petty session and prison records, which bring into focus the highly subjective way in which the term was employed. There is no mention of prostitute in the GRO/NC1E/1911 dataset but three women were returned as such in GRO/NC1E/1901; Mary Sweeney, Mary Barrett and Bridget Campion, aged 38, 21 and 25 respectively (Figure 10).Footnote 79 All three were coroner's cases and their lives were subjected to intense scrutiny.Footnote 80 The fact they were not recorded as prostitutes in the census raises the prospect that deaths of both male and female sex workers who died of certified natural causation may have been returned by the local registrar under different categories such as domestic service or room-keeping. Discussed in greater detail by Ciara Breathnach elsewhere, they merit a brief outline here: Barrett's death was accidental; she died at Jervis Street Hospital two days after receiving burns from pouring paraffin oil on a fire at 28 Lower Tyrone Street.Footnote 81 ‘Cardiac failure syncope’ was Sweeney's registered cause of death at 61 Montgomery Street in February 1901. The full verdict was that she died of ‘cardiac failure due to extensive tuberculosis with disease of the liver’.Footnote 82 Echoes of distrust in medico-legal authority permeate the testimony of witnesses: Sweeney had been ‘complaining of her chest’ for 18 months, but refused to see a doctor.

Figure 10. Location of the three women described as prostitutes in 1901 NC1E death records.

Source: Analysis of civil registration of death data 1901 and 1901 census of Ireland. Map created using OSi historic 25-inch basemap © Tailte Éireann/Government of Ireland Copyright Permit No. MP 001023.

That O'Casey's protagonist, 30-year-old Nannie, died because of excessive consumption of industrial alcohol was based on kernels of truth. Prosecutions for dealing ‘meths’ became a more publicized issue in the 1920s. But deaths arising from the consumption of spirits of unknown alcohol proof was certainly an issue in earlier decades.Footnote 83 Some clues to the consumption of industrial strength alcohol can be found in the coroner's records: for example, Bridget Campion's death due to ‘cardiac failure from excessive drinking’. It is not implausible that her death was caused by what she consumed.

Both Sweeney's and Campion's deaths concern aspects of what may be considered the occupational hazards of the spatial epidemiology of Monto and its heavy drinking culture. For example, in 1901, 247 cases of keeping or selling alcohol without a licence were brought against 49 men and 193 women, 50 of the 150 cases brought against licensed premises were in the DMP C (Rotunda) Division and 1,402 of the 4,829 cases in the ‘other than licensed premises’ category.Footnote 84 Finding crimes associated with illicit sale of porter is contingent on a newspaper report of the proceedings of Northern Police Court or a prosecution and imprisonment leading to an entry in the prison registers. Table 2 shows that 6 Faithful Place operated as a shebeen, as well as a brothel. Contradictory evidence was given at Campion's inquest: that she worked at 6 Faithful Place, a house ‘occupied’ by Henrietta Tully. Tully testified that she had been employed as a servant since 26 October and was previously employed in Miss Rice's Laundry, Blackhall Street. Further research shows that 6 Faithful Place was at the time an unoccupied house, and 7 Faithful Place was a private dwelling occupied by Ellen Walsh and her husband Patrick, but 2 Faithful Place was occupied by Henrietta Tully, who was also a prostitute (Table 2). The numbering system used in the census can be at variance with that used in other official records, so it is likely that this is a prostitute testifying for another prostitute. Servanthood in its occupational broadness was often used as a respectability indicator for unmarried women, and gave Tully an opportunity to afford Campion this dignity in death.

Conclusions

Combining the GRO and census data has great potential to reveal more about the lived experiences of marginalized people. But, as argued here, they must be viewed with a very critical eye. Not only have scholars to bear in mind the limitations of the original fields of inquiry, levels of discretion afforded to registrars and the DMP must be taken into account. This research exposes the layers, presuppositions and biases present within the creation and presentation of official statistics concerning the poor. It shows that mortality was linked to low income, lack of upward mobility, the urban penalty and intergenerational poverty. When civil registration of death is combined with census data, other discretionary powers come to the fore, which is why it is important to focus on location, to street level. In general, this research aimed to identify and examine mortality in young adult cohorts and the links to lower socio-economic status. It found a relationship between the absence of kinship networks and prostitution, which led to further risk factors. Mapping the death data brings into very sharp relief the level and localization of young adult mortality that was an accepted part of daily life in the poor city wards.

The overall findings of concern in the 1900 report for the 15–34 age cohorts are in evidence here. Despite high levels of mobility, NC1E sustained a closely knit community as neo-location was common, which explains why some prostitutes escape notice and others do not. Monto was a distinctly female-dominated commercial sex district; when the same search criteria regarding room-keeping and household formation patterns were applied to young men, they yielded no fruit. There was also a fluidity to the way women moved between sex work, low-paid work, and work that was paid in kind in the Magdalen Asylum. Census returns provide opportunities for self-fashioning, but known euphemisms in occupational terms, unusual household structures, the company people kept and the localization of commercial sex to a few streets provide avenues for historians to ascertain and map geographies of commercial sex work.

Funding statement

This research was generously funded by an Irish Research Council Laureate Award 2017/32.