A number of classic studies have shown that the risk of alcoholism runs in families (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Whitfield, Felitti, Chapman, Edwards, Dube and Williamson2002; Cotton, Reference Cotton1979; Schuckit & Smith, Reference Schuckit and Smith1996; Sher et al., Reference Sher, Walitzer, Wood and Brent1991). More recent studies have corroborated these findings and extended them to a range of patterns of drinking, including drinking and intoxication frequency and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores (Boden et al., Reference Boden, Newton-Howes, Foulds, Spittlehouse and Cook2019; Kendler, Ji et al., Reference Kendler, Ji, Edwards, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Sundquist2015; Mahedy et al., Reference Mahedy, MacArthur, Hammerton, Edwards, Kendler, Macleod, Hickman, Moore and Heron2018; McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Bogowicz, Meader, Kaner, Alderson, Craig, Geijer-Simpson, Jackson, Muir, Salonen, Smart and Newham2023; Rossow, Felix et al., Reference Rossow, Felix, Keating and McCambridge2016; Rossow, Keating et al., Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016;). However, the existing studies on the association of parental alcohol use with alcohol use of their children focus on adolescence and the early twenties, and whether these associations extend to later adulthood is uncertain (Mahedy et al., Reference Mahedy, MacArthur, Hammerton, Edwards, Kendler, Macleod, Hickman, Moore and Heron2018; Rossow, Felix et al., Reference Rossow, Felix, Keating and McCambridge2016; Rossow, Keating et al., Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016).

A previous study from the United States found that those who were on a high drinking trajectory from age 15 to 25 also had mothers and fathers who on average had a higher drinking frequency, with standardized difference in parental drinking frequency ranging from 0.28 (95% CI [0.02, 0.54]) to 0.55 (95% CI [0.26, 0.84]) (White et al., Reference White, Johnson and Buyske2000). Another study from the United States found that maternal drinking frequency was associated with heavy drinking of their 26-year old sons (odds ratio per unit increase in maternal drinking 1.75; 95% CI [1.11, 2.70]) (Englund et al., Reference Englund, Egeland, Oliva and Collins2008). Cohort studies from the Nordic countries support these findings. Parental alcohol consumption and binge drinking were associated with alcohol consumption and binge drinking in their children at age 28 (adjusted beta 0.09 [p < .001] for alcohol consumption and 0.13 [p < .001] for binge drinking; Pedersen & von Soest, Reference Pedersen and von Soest2013). Frequent paternal drinking was also associated with an increased risk of alcohol-related hospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio 1.73; 95% CI [1.47, 2.04]) and causes of death (adjusted hazard ratio 2.05; 95% CI [1.34, 3.13]) among their sons (Hemmingsson et al., Reference Hemmingsson, Danielsson and Falkstedt2017; Landberg et al., Reference Landberg, Danielsson, Falkstedt and Hemmingsson2018). By contrast, in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986, paternal and maternal drinking frequency had only weak correlations with offspring alcohol use disorder at age 28 (point biserial correlations .02–.05 of which only some were statistically significant; Parra et al., Reference Parra, Patwardhan, Mason, Chmelka, Savolainen, Miettunen and Järvelin2020). These studies have, however, assessed either alcohol consumption and binge drinking or alcohol-related diagnoses instead of a broader spectrum of alcohol-related problems. Yet, problem drinking affects many people, of which only a fraction receive an alcohol-related diagnosis (Connor et al., Reference Connor, Haber and Hall2016; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Goldstein, Saha, Chou, Jung, Zhang, Pickering, Ruan, Smith, Huang and Hasin2015; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Meader, Bird and Rizzo2012; Nyström et al., Reference Nyström, Peräsalo and Salaspuro1993).

To our knowledge, only two studies have assessed parental drinking in relation to offspring problem drinking in adulthood, and both had important limitations. In a Finnish study, parental drinking was associated with problem drinking of their 42-year-old sons (Pearson’s r .31 [p < .001]; Pitkänen et al., Reference Pitkänen, Kokko, Lyyra and Pulkkinen2008), but that study used a measure of problem drinking that had not been validated, and data on parental drinking were partly retrieved from offspring reports. A study from the United States found that heavy parental drinking was associated with symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence among their offspring at mid-thirties (Pearson’s r .12–.16; p < .001]; Merline et al., Reference Merline, Jager and Schulenberg2008), but this was based on attributions of parental drinking by the offspring, not parental self-assessments.

Many confounding factors may also be present. In their systematic review, Rossow, Keating et al. (Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016) proposed factors that could induce spurious associations between parental and offspring alcohol use. These included shared local environment, cultural and religious factors, and parental comorbidities and temperament. Related characteristics have also been associated with drinking behavior in earlier studies, supporting the idea that they might potentially confound the association between parental and offspring problem drinking (Edlund et al., Reference Edlund, Harris, Koenig, Han, Sullivan, Mattox and Tang2010; Gauffin et al., Reference Gauffin, Hemmingsson and Hjern2013; Kestilä et al., Reference Kestilä, Martelin, Rahkonen, Joutsenniemi, Pirkola, Poikolainen and Koskinen2008; Winter et al., Reference Winter, Karvonen and Rose2002). For example, local environment, availability of alcoholic beverages, and cultural and religious attitudes could influence the drinking of both parents and offspring, consequently creating associations between these two that are not related to parental drinking per se. Parental temperament could influence parental drinking and, through inheritance, also the temperament and drinking of the offspring.

To address limitations of earlier studies, we examined how paternal and maternal problem drinking are associated with lifetime problem drinking of their adult offspring, drawing on data from a population-based cohort study of Finnish twins and their parents. Problem drinking was prospectively individually reported by the different informants (parents and offspring) using comparable and validated measures. The offspring were assessed in their mid-twenties and mid-thirties, when they were approaching the age at which problem drinking of their parents was recorded, a time when most offspring had been living away from their childhood home for well over a decade. Our focus was on overall associations and not on potential mediating factors. However, we considered the confounding effects of several proposed confounders and the mediating effects of problem drinking in mid-twenties.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and the Study Cohort

The population-based FinnTwin16 cohort identified all twin births in Finland across five consecutive years (1975–1979) from the Finnish Population Information System (Kaidesoja et al., Reference Kaidesoja, Aaltonen, Bogl, Heikkilä, Kaartinen, Kujala, Kärkkäinen, Masip, Mustelin, Palviainen, Pietiläinen, Rottensteiner, Sipilä, Rose, Keski-Rahkonen and Kaprio2019). At baseline (wave 1), questionnaires were sent 10 times per year over 60 months to parents and twins such that the twins from the five successive birth cohorts received their questionnaires as close to their 16th birthday as possible. Follow-up waves were conducted at age 17 (wave 2), 18.5 (wave 3), 21–28 (wave 4, mid-twenties), and 31–37 (wave 5, mid-thirties).

In wave 1, 89.9% of the invited individual twins replied. Of those who had replied in wave 1, 85.4% replied also in wave 4 and 66.4% in both waves 4 and 5. In total, 5240 individuals (2415 men and 2825 women) returned a mailed questionnaire in wave 4 (mean age 24.5, range 21–28) and 4409 (1963 men and 2446 women) an electronic questionnaire in wave 5 (mean age 34.1, range 31–37) (Supplementary Figure 1). The main analyses of the present paper comprise lifetime drinking participants who had full data on relevant covariates, a total of 2696 participants (1235 men and 1461 women) in wave 4 and 2269 participants (991 men and 1278 women) in wave 5. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present an attrition analysis of study variables by inclusion versus exclusion to the study sample. Information on fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking and potential confounders was obtained with a mailed questionnaire administered at baseline, when the sons and daughters were aged 16 years.

The Ethics Committee of the Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki and the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University approved the data collection (waves 1–3) and analysis. Data collection for waves 4 and 5 was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Hospital Districts of Helsinki and Uusimaa and the Hospital District of Central Finland respectively.

Problem Drinking

We measured parental problem drinking with the Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Mm-MAST), which was designed for Nordic cultures. It consists of nine yes–no questions yielding scores ranging from 0 to 9 (Supplementary Table 3) (Kristenson & Trell, Reference Kristenson and Trell1982). High scores are a self-appraisal of drinking-related problems, and they are positively correlated with total alcohol consumption, intoxication frequency, and heavy drinking (Nyström et al., Reference Nyström, Peräsalo and Salaspuro1993; Seppä et al., Reference Seppä, Koivula and Sillanaukee1992; Seppä et al., Reference Seppä, Sillanaukee and Koivula1990). Fathers and mothers self-reported on their problem drinking in wave 1 when their sons and daughters were age 16. Because both fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST scores had highly skewed distributions, we categorized them by collapsing high scores into a single category (≥4). Suggested cut-offs to identify problem drinking vary from 2 to 4 (Kristenson & Trell, Reference Kristenson and Trell1982; Nyström et al., Reference Nyström, Peräsalo and Salaspuro1993; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Kaprio, Winter, Koskenvuo and Viken1999; Seppä et al., Reference Seppä, Koivula and Sillanaukee1992; Seppä et al., Reference Seppä, Sillanaukee and Koivula1990). Accordingly, we analysed both fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST in five categories comprising those who scored 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4.

The sons and daughters self-reported on their problem drinking in their mid-twenties (wave 4, age 21–28 years) and again in their mid-thirties (wave 5, age 31–37) with an extended, 11-item, lifetime version of Mm-MAST (Mm-MAST-11, Supplementary Table 3). The two additional items were added to make the scale a more sensitive measure of alcohol abuse and dependence (Kaprio et al., Reference Kaprio, Pulkkinen and Rose2002), and to increase its internal consistency (in our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .69 for fathers and .66 for mothers, for whom the original scale was used, but .78 and .75 for sons and daughters at mid-twenties and .78 and .77 for sons and daughters at mid-thirties, for whom the amended scale was used).

For both measures of problem drinking, Mm-MAST and Mm-MAST-11, we included all responses with no more than two missing items and substituted for the missing items the mean score of the available items of each included respondent. Substitutions were made for 6% of fathers and mothers and 1% of their adult children. Further, respondent parents (but not offspring) were instructed to skip the entire scale if they did not drink at all. Therefore, they received an Mm-MAST score of zero if all items were missing and they reported no alcohol drinks during the past year.

Heavy Drinking Occasions

We complemented our analyses of problem drinking with analyses of current heavy drinking occasions because they are an indicator of alcohol use disorder (Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Gmel, Gmel, Hasan, Imtiaz, Popova, Probst, Roerecke, Room, Samokhvalov, Shield and Shuper2017), mortality (Sipilä et al., Reference Sipilä, Rose and Kaprio2016), and high total alcohol consumption (Gmel et al., Reference Gmel, Kuntsche and Rehm2011). We defined heavy drinking occasions as consuming ‘within one occasion … more than five bottles of beer, or more than a bottle of wine, or more than half a bottle of hard liquor (or a corresponding amount of alcohol)’, which corresponds to consuming more than five standard drinks (>60 g of pure alcohol) on a single occasion. Fathers and mothers self-reported on their heavy drinking occasions in wave 1. We analysed their reports in five categories: (1) never, (2) once a year or less often, (3) a few times a year, (4) about once a month, and (5) about once a week or more often. From questionnaires administered to sons and daughters, we recorded current heavy drinking occasions at mid-twenties and mid-thirties in 10 categories, converting them to a continuous measure of heavy drinking occasions per year (range 0–365). The 10 categories and the corresponding numbers of yearly occasions were: I don’t use alcohol at all (0), never (0), once a year or less often (0.75), 3–4 times a year (3.5), about once in two months (6), about once a month (12), a couple of times a month (24), about once a week (52), about twice a week (104) and daily (365). As with problem drinking, lifetime abstainers were excluded.

Lifetime Abstinence

Because the determinants of abstinence are known to be different from the determinants of drinking habits among those who drink (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Woodard, Murrelle, Meyer, Silberg, Hewitt, Rutter, Simonoff, Pickles, Carbonneau, Neale and Eaves1999; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Dick, Viken and Kaprio2001; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Kaprio, Winter, Koskenvuo and Viken1999; Viken et al., Reference Viken, Kaprio and Rose2007), we excluded from our primary analyses those who reported themselves to be lifetime abstainers. Consequently, we excluded fathers of 317 adult children (7%), mothers of 617 adult children (12%), 215 adult children in their mid-twenties (4%), and 118 adult children in their mid-thirties (3%). To test the effects of these exclusions, we conducted sensitivity analyses with abstainers included.

Potential Confounders

We stratified all models by sex. Partial adjustment for age was inherent to data collection, which was done in waves at defined ages. As detailed below, we also adjusted the multivariate models for best available proxies for socioeconomic status of the family, family situation, and parental and family characteristics suggested to be potentially important in a systematic review by Rossow, Keating et al. (Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016). All covariates were measured in wave 1 when the twins were 16 years old. To avoid over-adjustment, we did not adjust for offspring characteristics, because they may mediate the associations between parental and offspring problem drinking.

Fathers and mothers self-reported their education in wave 1. This information was analysed as a dichotomy separately for fathers and mothers: academic (completed high school) vs. nonacademic (did not attend or complete high school).

Family structure was self-reported by the sons and daughters in adolescence (wave 1) and analysed as a dichotomy of whether (or not) they were living with both biological parents at age 16.

Area of residence reflected the local environment and cultural milieu. It was retrieved from the Finnish Population Information System in the last year of wave 1 and was classified according to the European Union’s Nomenclature of Territorial Units (Rose et al., Reference Rose, Kaprio, Winter, Koskenvuo and Viken1999; Statistics Finland, 1998). We analysed area of residence in three categories characterized by high, low, and intermediate average alcohol consumption (capital area, Mid-Finland and West coast, and the rest of Finland respectively; Simpura & Lahti, Reference Simpura and Lahti1988).

We measured fathers’ and mothers’ religiosity using the religious fundamentalism content scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) consisting of 12 yes–no items about religious practice and beliefs, with an emphasis on the tenets of Christianity, which is the majority religion in Finland (Sipilä et al., Reference Sipilä, Harrasova, Mustelin, Rose, Kaprio and Keski-Rahkonen2017; Wiggins, Reference Wiggins1966; Winter et al., Reference Winter, Karvonen and Rose2002). The observed scores spanned the entire theoretical range from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating higher religiosity. The scale was included in the parents’ questionnaire mailed to them at baseline (wave 1). We included those answering at least nine items, with the mean score of the available items substituted for missing items.

We assessed a risk-relevant dimension of fathers’ and mothers’ personality using a 50-item social deviance scale (the Pd or ‘Psychopathic deviate’ scale of the MMPI), a proxy for parental comorbidity and temperament. Although the theoretical range is from 0 to 50, the observed scores ranged from 5 to 42 for fathers and from 3 to 36 for mothers with higher scores reflecting higher social deviance. The scale is also associated with problem drinking (Mustanski et al., Reference Mustanski, Viken, Kaprio and Rose2003; Viken et al., Reference Viken, Kaprio and Rose2007) and captures part of the genetic risk for externalizing disorders in the family, as common genetic background contributes to the comorbidity of externalizing disorders (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Prescott, Myers and Neale2003). The scale was included in the parents’ questionnaire at baseline (wave 1). We included participants who had completed at least 40 items. Mean score of the available items was substituted for missing items. The proportion of respondents with data available for problem drinking, religiosity, and the Pd scale before and after the substitutions are reported in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated polychoric correlations between ordinal variables (Kolevnikov & Angeles, Reference Kolevnikov and Angeles2004), also treating sons’ and daughters’ reports on heavy drinking occasions as ordinal for the purpose of correlation analysis. We assessed the underlying bivariate normality assumption with Pearson’s chi-squared tests; significant p values warrant careful interpretation of the estimated polychoric correlations. For that reason, we also report Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rho) for comparison for correlations with evidence for violation of the underlying bivariate normality assumption. Because sons’ and daughters’ problem drinking was assessed continuously, we estimated polyserial correlations between them and ordinal variables (Kolevnikov & Angeles, Reference Kolevnikov and Angeles2004).

In multivariate analysis, we estimated sons’ and daughters’ problem drinking (mean Mm-MAST-11) using multiple linear regression analysis. In contrast, we used generalized linear models with log link and Poisson distribution to estimate sons’ and daughters’ mean heavy drinking occasions per year because the distribution of heavy drinking occasions was highly skewed. Further, we applied robust variance estimators to get unbiased confidence intervals despite heteroscedasticity and overdispersion (Cameron & Trivedi, Reference Cameron, Trivedi and Press2010; Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010). To allow for nonlinear relations, and thus, to reduce residual confounding, we modelled religiosity and personality with restricted cubic splines with three knots at 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles (Harrell, Reference Harrell2015). We tested for differences in associations of sons’ versus daughters’ problem drinking with fathers’ versus mothers’ problem drinking using Wald tests. We adjusted all confidence intervals for clustering within twin pairs (Williams, Reference Williams2000). All p values are two-sided; p < .05 was considered statistically significant. We analysed the data using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

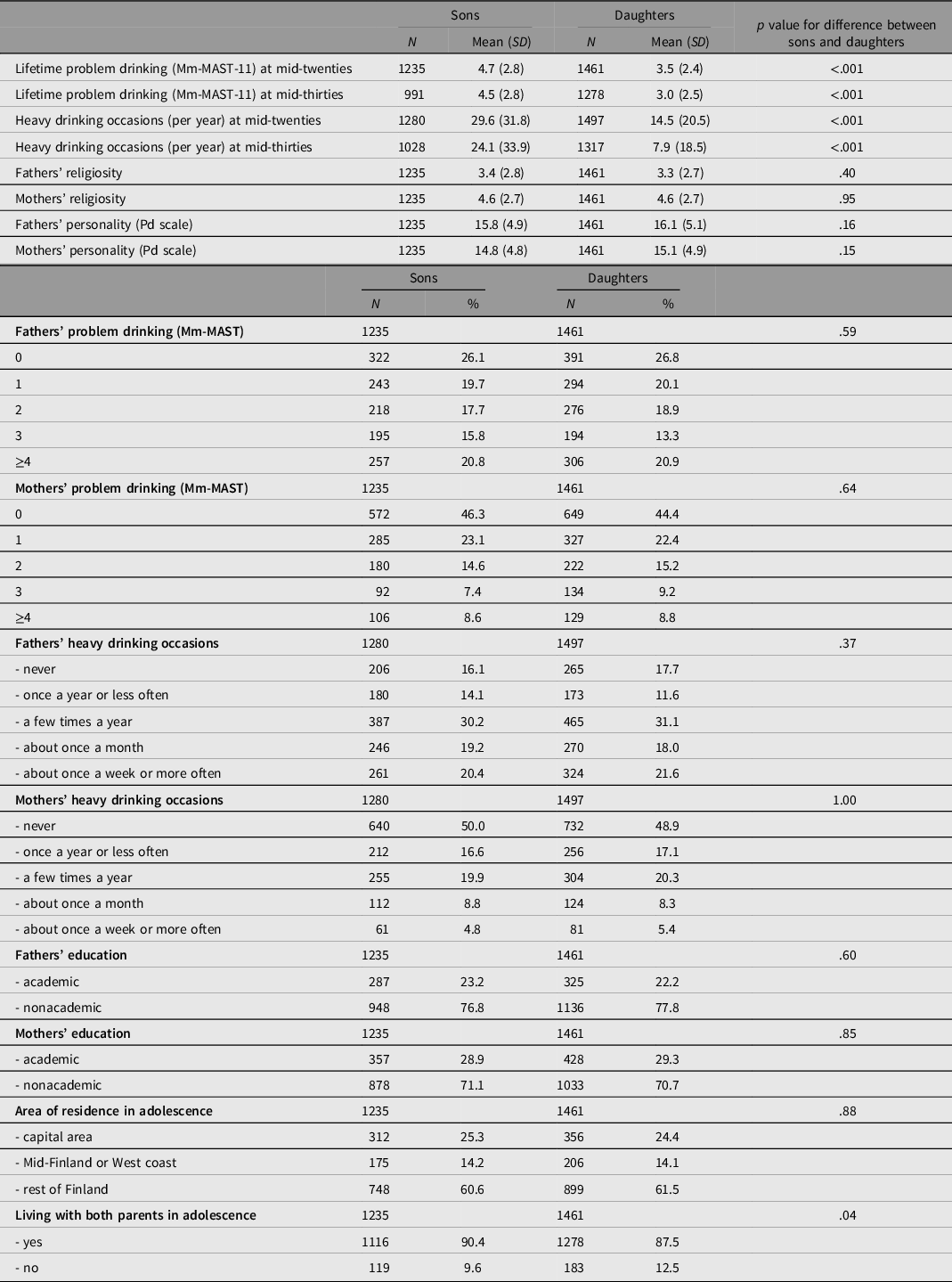

Table 1 summarizes problem drinking, heavy drinking occasions, and potential confounders among study participants who were not lifetime abstainers. Fathers reported more problem drinking than mothers: 20.9% of fathers (95% CI [18.8, 23.1]), but only 8.7% of mothers (95% CI [7.4, 10.3]) scored ≥4 on the Mm-MAST. Similarly, sons reported more problem drinking than did daughters (e.g., mean lifetime Mm-MAST-11 at mid-thirties was 4.5 for sons and 3.0 for daughters, p for difference <.001).

Table 1. Basic characteristics of lifetime drinkers in the study cohort

Note: The numbers represent those without missing information on the characteristic in question. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; Mm-MAST, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (original 9-item version); Mm-MAST-11, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (extended 11-item version); Pd scale, Pd or “Psychopatic deviate” scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.

Correlations

Table 2 presents polyserial and polychoric correlations between measures of problem drinking and heavy drinking occasions. The correlations of these measures of drinking with covariates are shown in Supplementary Table 4. Correlations between parents’ problem drinking and their children’s lifetime problem drinking were very modest (.09–.18). Correlations between parents’ and their children’s current heavy drinking occasions were similar (.12–.19). Correlation between fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking was .40 and between fathers’ and mothers’ heavy drinking occasions it was .46. The correlations remained similar when the analyses were restricted to those who were living with both biological parents at age 16 (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2. Correlations between measures of problem drinking and heavy drinking occasions

Note: *p < .01, **p < .001.

a Pearson’s chi-squared test indicates violation of the underlying bivariate normality assumption.

Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficients (rho) given for comparison in parentheses for those polychoric correlations for which there was evidence for violation of the underlying bivariate normality assumption. Lifetime abstainers were excluded from the analysis.

Mm-MAST, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (original 9-item version); Mm-MAST-11, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (extended 11-item version).

Multivariate Models of Problem Drinking

We included fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking simultaneously in the same model to assess their associations with offspring’s problem drinking independently from each other (Tables 3 and 4). Fathers’ high problem drinking was associated with higher lifetime problem drinking in their sons and daughters measured in their mid-twenties and mid-thirties, even after adjustment for mothers’ problem drinking. P values for linear trend were significant for all these comparisons. The associations of mothers’ problem drinking with lifetime problem drinking in offspring at both mid-twenties and mid-thirties showed similar patterns to fathers’ problem drinking, although the associations failed to reach statistical significance for many comparisons. P values for linear trend were significant for the associations of maternal problem drinking with sons’ lifetime problem drinking, but not with daughters’ lifetime problem drinking. Yet, the differences between the associations of paternal and maternal problem drinking with offspring lifetime problem drinking were not statistically significant and, as indicated by the highly overlapping confidence intervals, the associations of fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking with their sons’ versus daughters’ lifetime problem drinking were of comparable strength.

Table 3. Association of fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking with lifetime problem drinking of offspring at mid-twenties

Note: Model 1 includes simultaneously fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST. Model 2 includes simultaneously fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST + adjustments for fathers’ religiosity, mothers’ religiosity, fathers’ personality, mothers’ personality, fathers’ education, mothers’ education, area of residence, and family structure. Lifetime abstainers excluded. Offspring problem drinking measured using Mm-MAST-11.

a Reference category

b p value for difference with the reference category.

CI, confidence interval; Mm-MAST, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (original 9-item version); Mm-MAST-11, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (11-item version).

Table 4. Association of fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking with lifetime problem drinking of offspring at mid-thirties

Note: Model 1 includes simultaneously fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST. Model 2 includes simultaneously fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST + adjustments for fathers’ religiosity, mothers’ religiosity, fathers’ personality, mothers’ personality, fathers’ education, mothers’ education, area of residence, and family structure. Lifetime abstainers excluded. Offspring problem drinking measured using Mm-MAST-11.

a Reference category

b p value for a difference with the reference category.

CI, confidence interval; Mm-MAST, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (original 9-item version); Mm-MAST-11, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (11-item version).

We tested whether adjustments for area of residence, family structure, and fathers’ and mothers’ education, religiosity and personality would affect our results. The magnitude and direction of the associations remained the same (Model 1 vs. Model 2 in Tables 3 and 4). Further, the observed associations were slightly stronger when lifetime abstainers were included, suggesting that our approach of excluding lifetime abstainers was conservative (Supplementary Tables 6–8).

Mediating Role of Problem Drinking at Mid-Twenties

The association of fathers’ problem drinking with lifetime problem drinking of their offspring at mid-thirties was considerably attenuated when adjusted for lifetime problem drinking of their offspring at mid-twenties (Table 5). The associations of mothers’ problem drinking were attenuated even more.

Table 5. The contribution of offspring problem drinking at mid-twenties on the association of fathers’ and mothers’ problem drinking with lifetime problem drinking of offspring at mid-thirties

Note: Model 2 includes simultaneously fathers’ and mothers’ Mm-MAST + adjustments for fathers’ religiosity, mothers’ religiosity, fathers’ personality, mothers’ personality, fathers’ education, mothers’ education, area of residence, and family structure. Model 3 is as model 2 but additionally adjusted for offspring problem drinking (Mm-MAST-11) at mid-twenties. Lifetime abstainers excluded.

a Reference category

b p value for a difference with the reference category. CI, confidence interval; Mm-MAST, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (original 9-item version); Mm-MAST-11, Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (11-item version).

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, we observed a modest association between paternal problem drinking and lifetime problem drinking of their adult children. This association could be detected even when the children’s problem drinking was assessed at mid-thirties (i.e., almost two decades after the fathers had reported their problem drinking). And this association remained similar after controlling for family and individual parental characteristics. Maternal problem drinking showed a similar, but less statistically robust association with problem drinking of adult offspring.

Many studies have found associations between alcohol use of parents and their children in adolescence and in their twenties (Mahedy et al., Reference Mahedy, MacArthur, Hammerton, Edwards, Kendler, Macleod, Hickman, Moore and Heron2018; Rossow, Felix et al., Reference Rossow, Felix, Keating and McCambridge2016; Rossow, Keating et al., Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Cheong, Zaravinos-Tsakos, Lubman and Jorm2017). This study extends these findings into lifetime problem drinking measured during the third and fourth decades of life (mean age 24.5 and 34.1 years, respectively), when offspring have been living in adulthood for well over a decade and are approaching the age at which their parents’ problem drinking was assessed (fathers’ mean age 46.0 years, mothers’ mean age 44.0 years). However, the associations of parental problem drinking with offspring lifetime problem drinking at mid-thirties could be substantially explained by offspring lifetime problem drinking at mid-twenties, highlighting the importance of the third decade of life as a critical period for problem drinking.

Our results are compatible with the few earlier studies on the association between parental alcohol use and later alcohol use among adult offspring. In a cohort study from Norway, the correlations of combined parental alcohol consumption and binge drinking with alcohol consumption and binge drinking of their children ranged from .09 to .16 (Pedersen & von Soest, Reference Pedersen and von Soest2013). In our study, correlations ranged from .09 to .18. In other cohort studies from the United States, both mothers’ and fathers’ drinking frequency were associated with a higher probability of being on a heavy drinking trajectory from late adolescence to mid-twenties (White et al., Reference White, Johnson and Buyske2000), and parental heavy drinking was associated with heavy drinking and symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence of offspring at age 35 years (Pearson’s r .12–.16; Merline et al., Reference Merline, Jager and Schulenberg2008). In a Finnish cohort study, parental drinking was associated with problem drinking among their sons in their forties (Pearson’s r 0.31; Pitkänen et al., Reference Pitkänen, Kokko, Lyyra and Pulkkinen2008).

The correlations of .09–.18 observed in our study indicate that parental problem drinking might explain 1–3% of the variation in offspring problem drinking. This is relatively modest, but well consistent with previous estimates from observational (1–10%) and genetic studies (single-nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] heritability 4%; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Jiang, Wedow, Li, Brazel, Chen, Datta, Davila-Velderrain, McGuire, Tian, Zhan, Choquet, Docherty, Faul, Foerster, Fritsche, Gabrielsen and Vrieze2019; Merline et al., Reference Merline, Jager and Schulenberg2008; Pedersen & von Soest, Reference Pedersen and von Soest2013; Pitkänen et al., Reference Pitkänen, Kokko, Lyyra and Pulkkinen2008). These findings suggest that there is substantial variation in problem drinking that cannot be traced back to the problem drinking of previous generations. Consequently, although potentially very beneficial for the targeted individuals, interventions addressing problem drinking on the individual level can be expected to have only modest effects on the problem drinking of subsequent generations. This highlights the need for multigenerational approaches that pay adequate attention to the situation and needs of each individual generation.

In our study, maternal problem drinking showed weaker correlations with lifetime problem drinking of adult offspring than did paternal problem drinking. When both paternal and maternal problem drinking were simultaneously considered in the same model, maternal problem drinking had again weaker associations with offspring problem drinking than did paternal problem drinking. Although the difference was not statistically significant, it was consistent across several analyses. However, in earlier studies the findings have been inconsistent (Alati et al., Reference Alati, Baker, Betts, Connor, Little, Sanson and Olsson2014; Mahedy et al., Reference Mahedy, MacArthur, Hammerton, Edwards, Kendler, Macleod, Hickman, Moore and Heron2018; Mares et al., Reference Mares, van der Vorst, Engels and Lichtwarck-Aschoff2011; White et al., Reference White, Johnson and Buyske2000). Further studies are necessary to examine the differential associations of fathers’ versus mothers’ drinking with their offspring’s drinking.

Associations between parental and offspring alcohol use are at least partly explained by dispositional genetic factors inherited by the children (Hopfer et al., Reference Hopfer, Crowley and Hewitt2003; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Jiang, Wedow, Li, Brazel, Chen, Datta, Davila-Velderrain, McGuire, Tian, Zhan, Choquet, Docherty, Faul, Foerster, Fritsche, Gabrielsen and Vrieze2019; Verhulst et al., Reference Verhulst, Neale and Kendler2015; Walters et al., Reference Walters, Polimanti, Johnson, McClintick, Adams, Adkins, Aliev, Bacanu, Batzler, Bertelsen, Biernacka, Bigdeli, Chen, Clarke, Chou, Degenhardt, Docherty, Edwards and Fontanillas2018). Those could be further assessed using genetic data and co-twin designs. However, at least the familial aggregation of alcohol use disorder cannot be fully explained by shared genetic predisposition (Kendler, Ji et al., Reference Kendler, Ji, Edwards, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Sundquist2015; Kendler, Ohlsson et al., Reference Kendler, Ohlsson, Sundquist and Sundquist2015). Besides shared genetic dispositions, assortative mating can substantially contribute to parent–offspring similarities (Ruby et al., Reference Ruby, Wright, Rand, Kermany, Noto, Curtis, Varner, Garrigan, Slinkov, Dorfman, Granka, Byrnes, Myres and Ball2018). Consistent with significant assortative mating, paternal and maternal problem drinking were correlated at .40 in our data, although this correlation may also reflect changes in the drinking patterns of one or both of the parents during the time they have lived together.

Nongenetic familial mechanisms may also contribute to the associations between parental and offspring problem drinking. Parental problem drinking may influence parenting and increase stress in the family (Leonard & Eiden, Reference Leonard and Eiden2007), possibly activating a genetic predisposition to alcohol use in offspring (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Waterman, Heath, True, Bucholz, Haber, Scherrer and Fu2003; Rossow, Keating et al., Reference Rossow, Keating, Felix and McCambridge2016). Parental monitoring, discipline, and alcohol rules may mediate these effects (Latendresse et al., Reference Latendresse, Rose, Viken, Pulkkinen, Kaprio and Dick2008; Sharmin et al., Reference Sharmin, Kypri, Khanam, Wadolowski, Bruno, Attia, Holliday, Palazzi and Mattick2017). In addition, parents who drink may have more approving attitudes towards alcohol drinking, will probably have alcohol in the household, and may even be more inclined to supply alcohol to their children, which may increase the children’s problem drinking (Maggs & Staff, Reference Maggs and Staff2018; Mattick et al., Reference Mattick, Clare, Aiken, Wadolowski, Hutchinson, Najman, Slade, Bruno, McBride, Kypri, Vogl and Degenhardt2018; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Cheong, Zaravinos-Tsakos, Lubman and Jorm2017). Further, family structure (which we controlled for) and social networks may be both confounders and mediators (Delucchi et al., Reference Delucchi, Matzger and Weisner2008; Leonard & Rothbard, Reference Leonard and Rothbard1999). However, these proposed nongenetic familial mechanisms mainly operate when the parents and their children live together. Future studies are needed to assess whether their effects extend to the adulthood of the offspring.

This study had some limitations. Our measures were based on self-reports (with the exception of age, sex, and area of residence, which were retrieved from the Finnish Population Information System) and are subject to reporting error. Childhood characteristics were not assessed, because baseline assessments were in mid-adolescence. Data on offspring problem drinking using Mm-MAST were not collected at baseline at age 16, but the duration and quantity of drinking will have been quite limited for most children at that age. The measures of problem drinking administered to parents and offspring were not identical. The sons’ and daughters’ questionnaires assessed lifetime problem drinking and could not differentiate between current and past drinking problems. Nonetheless, when assessing current heavy drinking occasions reported by the sons and daughters in their mid-twenties and mid-thirties, we found similar correlations.

As with most longstanding studies, attrition and missing information on individual items was considerable and may cause bias; both abstainers and heavy drinkers may have been more prone to nonresponse (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Goldstein, Pickering and Grant2014). Heavy-drinking individuals may underreport their drinking (Northcote & Livingston, Reference Northcote and Livingston2011), and drinking may vary over time (Knott et al., Reference Knott, Bell and Britton2018). Further, parental questionnaires did not specifically enquire about past drinking problems, which may have led to misclassification of former problem drinkers and underestimation of true associations. Moreover, the determinants of problem drinking are complex (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Becker, Huber and Catalano2012). Some residual confounding due to unidentified or imprecisely measured covariates is likely present. Finally, lack of statistical significance in some comparisons cannot be interpreted as evidence for no association, as our confidence intervals are also compatible with modest associations.

The main strength of this study is its intergenerational design, with participants of each generation themselves reporting their alcohol use. We investigated a prospective population-based cohort with high response rates. We assessed both problem drinking and heavy drinking occasions across time with validated measures. In addition, both of the offspring assessments were completed 10 years apart in adulthood when patterns of alcohol use begin to stabilize (Knott et al., Reference Knott, Bell and Britton2018; Maggs & Schulenberg, Reference Maggs and Schulenberg2004).

In conclusion, in this population-based cohort study, parental problem drinking was modestly associated with lifetime problem drinking of their adult children. This association could be detected even when the children had reached the fourth decade of life.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2023.12

Acknowledgment

We thank statistician Paula Bergman for help with the supplementary figures and Dr Kateryna Golovina for insightful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Financial support

PNS has been supported by the Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, the Helsinki Institute of Life Science, and the Finnish Medical Foundation during the conduct of the study. JK has been supported by the Academy of Finland (grants 265240, 263278, 308248, and 312073). FinnTwin16 data collection has been supported by AA08315, AA00145, and AA12502 to RJR from USPHS/NIH and grants 100499, 205585, 118555, and 141054 from the Academy of Finland to JK. The funders had no role in the design or execution of the study, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

PNS has been supported by the Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.