Introduction

Imagine. You are on the dance floor, working up a sweat while moving your hands and feet. Your mind and body are in sync with the beat, and you are feeling the rhythmic grooves over and over. Suddenly, the beat stops. Only a bass line remains, and without the drums it is harder to make sense of the rhythm. Soon the sound becomes distorted, and new rhythms are added. It feels like new sounds are surrounding you. Your body stops dancing as your mind tries to comprehend the new aural information.

This is a common experience when listening to electronic dance music (EDM), and especially house music, which is one of the broadest and most popular genres heard at EDM festivals.Footnote 1 Moments of disorientation are important counterpoints to the usual repetition that dancers experience. Repetition as an ‘aesthetic strategy’ is desired most of the time in EDM,Footnote 2 with mechanistic drum patterns and other rhythmic grooves clearly establishing metre and listeners entraining to it. In most house tracks and performances, however, there are sections when the repetition is broken and significant changes occur.

For example, on the track ‘Everything Before’ from the album Everything is Complicated by deadmau5 (aka Joel Zimmerman), the drums and other percussion sounds suddenly stop at 4:00, leaving only low-pitched loops in the texture (see Example 1).Footnote 3 Some of these sound layers are carried over from the previous section, but others are new or transformed. At first it is easy for dancers to maintain a clear sense of metre, despite some syncopation and the absence of the drums. However, with each subsequent two-bar repetition, the echo effect creates more and more different rhythms using the upper two notes (F♯ and C). The composite rhythm of the synth part soon becomes constant semiquavers. Then more layers are added, creating more metrical dissonance and confusion. Some fade in and crescendo, and one enters (at 4:15, about halfway through this section) with a sharp timbre on an offbeat, articulating a three-semiquaver pulse that is dissonant with the beat.

Example 1 Transcription of the start of the breakdown (4:00) in ‘Everything Before’ by deadmau5 (2007).

The right and left speakers are also used differently for the synth layer in Example 1, as is evidenced by listening to the section with only one speaker or the other. The right speaker mostly projects quavers throughout, although the timbre seems to change so that the attack gets more muddled. In the left speaker, more complicated cross-rhythms are introduced, in addition to the initial rhythm.Footnote 4

By the end of the section, it is difficult to mentally retain which one (if any) of the many sound layers is articulating the initial pattern, and in my own experience it is easy to lose the beat. This is also partially because the layer called bass 1 in Example 1 – which had helped retain some sense of hypermetre and where the downbeats are by repeating its motive every two bars – does not repeat for the last two bars in the section. Therefore, at the end of the section (4:23–4:30) four bars of metrically dissonant sounds in the synth layer predominate and overwhelm the texture.

A continuous noise sweep at the end provides a sense of anacrusis to the next section, but this cue is hard to interpret without clear rhythmic pulses.Footnote 5 When the next section starts, the re-introduction of the drums engenders a sense of relief. This example from ‘Everything Before’ demonstrates an important part of house-music aesthetics: disorientation followed by clarification.Footnote 6

Disorientation as an aesthetic strategy is most commonly used in one particular sectional type within a house track or performance: the breakdown. This article discusses how and why disorientation is used in breakdown sections of house tracks and performances, from the perspective of both producers and dancers. Through my analyses of several pieces and performances by contemporary house artists, and interviews with producers of various EDM genres, I show how the techniques used in breakdown sections play an important role in the understanding of musical narratives for this repertoire.

I have chosen to focus on artists primarily known in the ‘festival-house’ scene rather than ‘underground’ house artists because I am interested in how these musical techniques are employed when performing for large audiences and because I have significant experience attending festival concerts that can help reveal tendencies in these performances. House music started as a localized scene in Chicago, led by queer African-American DJs such as Frankie Knuckles, and there are still many local house scenes that are thriving facets of queer nightlife.Footnote 7 However, over the last decade or so, there has been worldwide growth in the EDM-festival scene, which often features superstar artists playing house music.Footnote 8 Some people say this type of music is not real ‘house’ because of its mainstream, commercialized settings, but popular terms associated with EDM festivals include ‘progressive house’, ‘electro house’, and ‘big-room house’.Footnote 9

Breakdowns and EDM genres

This section contextualizes the meaning of the term ‘breakdown’ in EDM generally, focusing particularly on the formal structures of festival-house music and comparing them with other EDM styles or scenes. As a starting point, it is important to understand that breakdowns are different than ‘breaks’. The latter term has a long history within African-American musical traditions, but is often associated with solo drum sections of funk tracks.Footnote 10 In the 1970s, drum breaks were sampled by early hip-hop artists to create ‘breakbeats’ that were often used for ‘breakdancing’.Footnote 11 Later, breakbeats were sped up by many EDM producers and they became the foundation for some EDM genres such as hardcore, jungle, drum & bass, and big beat.Footnote 12 The EDM ‘breakdown’ is also distinct from ‘breakdowns’ in other popular music genres such as metal, punk, and bluegrass.Footnote 13

In EDM, breakdowns are defined by their thin texture and relatively quiet volume. Most tracks have one or two breakdowns that are generally in the middle area, just before buildups and then climactic drops. Producer Rick Snoman says that breakdowns are defined by ‘removing most of the instrumentation from the mix’.Footnote 14 There are many ways to do this, and different emphases in breakdown sections are one of the many factors involved in genre distinctions within the EDM umbrella.Footnote 15

One important consideration is how much of the drumbeat remains in the breakdown. Some EDM genres usually keep the drums in, such as drum ’n’ bass and dubstep, which fall within the category of ‘bass music’. Producer Tyler Marenyi (aka NGHTMRE) works primarily in these genres, and he told me that breakdowns have less drums or quieter drums, as opposed to climactic sections when ‘the drums are my loudest element’.Footnote 16 Trance, on the other hand, is known for long breakdown sections when drums are completely absent, as producer Db Mokk told me.Footnote 17 House music provides an interesting case study because the presence of drums in house breakdowns is more variable. The kick drum (which is the primary marker of house's four-on-the-floor beat) is often removed or ‘withheld’,Footnote 18 but sometimes, as producer Joe Smooth told me, the kick is one of the only elements left in, and it is just ‘EQ'ed a little lighter’.Footnote 19 Other times, all or almost all of the drums are absent in house breakdowns, reminiscent of trance.

Another consideration is what comes to the fore in the mix during breakdowns. For bass music, Marenyi says breakdowns are a time to highlight something that has previously taken more of a ‘back seat’ such as a vocal line or any melody.Footnote 20 In house and trance music, breakdowns often introduce a new and unique sound layer, which stands out in the thin texture and is usually foregrounded in the mix.Footnote 21 Sometimes it is a new melody that will be a countermelody in the next main section with all the primary sound layers of the track.

In most types of house music, breakdowns are also known for their high concentration of electronic ‘effects’ such as filtering and echo/delay, which is different from other genres that use effects prominently throughout. Producer Man Parrish described breakdowns as the ‘producer's playground’: ‘Now the effects come in, now you're going down that rabbit hole, now the aliens come down with a spaceship and you have all those star fields and special effects.’Footnote 22 Many of these effects can be considered ‘continuous processes’ (musical gestures that feature continuous movement as opposed to discrete movement), which can fulfil musical roles of ornamentation, orientation, or disorientation.Footnote 23

For dancers, the aesthetic effects of breakdowns differ depending on the genre and the live setting. In bass-heavy EDM, breakdowns provide brief moments of ‘easy listening’ for dancers, when the sub-bass frequencies are temporarily lifted off in a way that can be felt physically.Footnote 24 Long trance breakdowns allow dancers to settle in to the new ‘dreamy’ elements such as harmonic progressions and to get comfortable with the lack of drums.Footnote 25 In house breakdowns, electronic effects often combine with highly syncopated or metrically dissonant riffs, and when the kick drum is absent, this can disorient dancers from the primary beat of the track. Joe Smooth told me some dancers move significantly less during breakdowns, while others try and keep moving to the previously established beat: ‘Sometimes it drops out and you're like OK what? Where am I? What's going on? Then you can take pictures or check your email. But then when the snare rolls and stuff come back in, the rhythm comes back in, [and] it brings you back into the build.’Footnote 26 This description implies that for dancers the disorientation in breakdown sections can be physical and/or psychological, which correlates with the results from an empirical study on the body movements and cognitive perceptions of dancers during a simulated house-club environment.Footnote 27 Dancers also influence each other. Different festivals, scenes, and crowds each have their own cultural histories and expectations for how to react to breakdowns.

From the performer's or producer's perspective, having an aesthetic of disorientation in the middle of a track can serve multiple purposes, such as providing contrast that makes upcoming musical climaxes more exciting and allowing an opportunity for dancers to physically rest. As subsequent analyses show, it also encourages visual interaction between the performer and the dancers and allows the performer to communicate a narrative with the audience through musical or lyrical meaning. This is similar to how middle sections of many pop and rock songs have an aesthetic of intimacy.Footnote 28

Most of the analyses in this article are of published tracks as fixed ‘texts’, as opposed to live performances.Footnote 29 This is not ideal given the claims I make about the effects of disorientation in live settings. However, most festival EDM performances keep the formal structure of tracks recognizable from their published versions and only include small tweaks or embellishments to imbue the performance with a sense of liveness.Footnote 30 This is a significant change in performance practice compared with that from the early decades of EDM and has to do with the increased commercialization of EDM.Footnote 31 It is also important to keep in mind that many people listen to EDM in non-live contexts too; for example, while cooking at home, walking on the streets, or working out at the gym.

Before proceeding with analytical case studies of breakdowns, it is important to clarify that not all moments of aesthetic disorientation occur in breakdown sections. Some occur in other sections such as the intro or outro.Footnote 32 However, I argue that all breakdown sections in house music are disorienting for dancers to at least some degree. Some are much more disorienting than others though, particularly metrically. In the uncommon scenario when breakdown sections only feature the kick drum or a simple drum pattern, listeners can easily maintain metric entrainment, but may be disoriented through the absence of melodic or rhythmic grooves they were used to. Some breakdown sections remove many sound layers and have a significant decrease in volume, while others feature just a small decrease in volume or the number of layers. Therefore, it is useful to think of a continuum for the degree of disorientation in breakdown sections.

A final important clarification is that the breakdown does not always have a clear ending point. Usually, there is a clearly marked buildup section following the breakdown, with the buildup then leading to the drop. Some scholars use the term ‘break routine’ to refer to this tripartite schema that is particularly associated with festival EDM.Footnote 33 Buildup sections are characterized by an increase in sonic intensity typically created through the gradual addition of sound layers, filter sweeps, crescendos, and ascending pitch gestures known as risers.Footnote 34 Sometimes, however, the breakdown leads fluidly into a buildup, so that only one formal section is perceived, similar to a bridge section in a standard pop/rock song form. In such cases, the term ‘breakdown-buildup’ is preferred, and some scholars only use the term ‘breakdown’ for the section encompassing both.Footnote 35 It is rarer for breakdown sections to not have a clear starting point, at least in house music. Other genres such as techno are more subtle or ambiguous in terms of formal sections, featuring less obvious buildups and drops.Footnote 36

The remainder of this article examines tracks by three different artists (Chunda Munki, Cassy, and Walker & Royce) before concluding with more discussion about various roles of breakdown sections in festival-house performances. The tracks chosen for analysis are case studies that exemplify the techniques and creative philosophy outlined in this section.

‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki (Reference Munki2017)

One track that has an aesthetic of disorientation in its breakdown sections is ‘Interferance’ (sic) by the South African artist Chunda Munki (aka Blayze Saunders). As a self-proclaimed autodidact, Saunders learned techniques for making electronic music from a young age.Footnote 37 Now his bio pages proudly declare him as a house artist that tours internationally and performs at many festivals.Footnote 38 He has three LP albums released to date: Just Woke Up (2022), Strange Things (2019), and Interference (2017). The latter album features ‘Interferance’, which will be discussed here. A form chart of the track is shown in Table 1, using the term ‘core’ instead of ‘drop’ for the climactic sections.Footnote 39 This track is unusual in that it has three breakdown sections, instead of the usual one or two, and each of them is significantly different from the others.

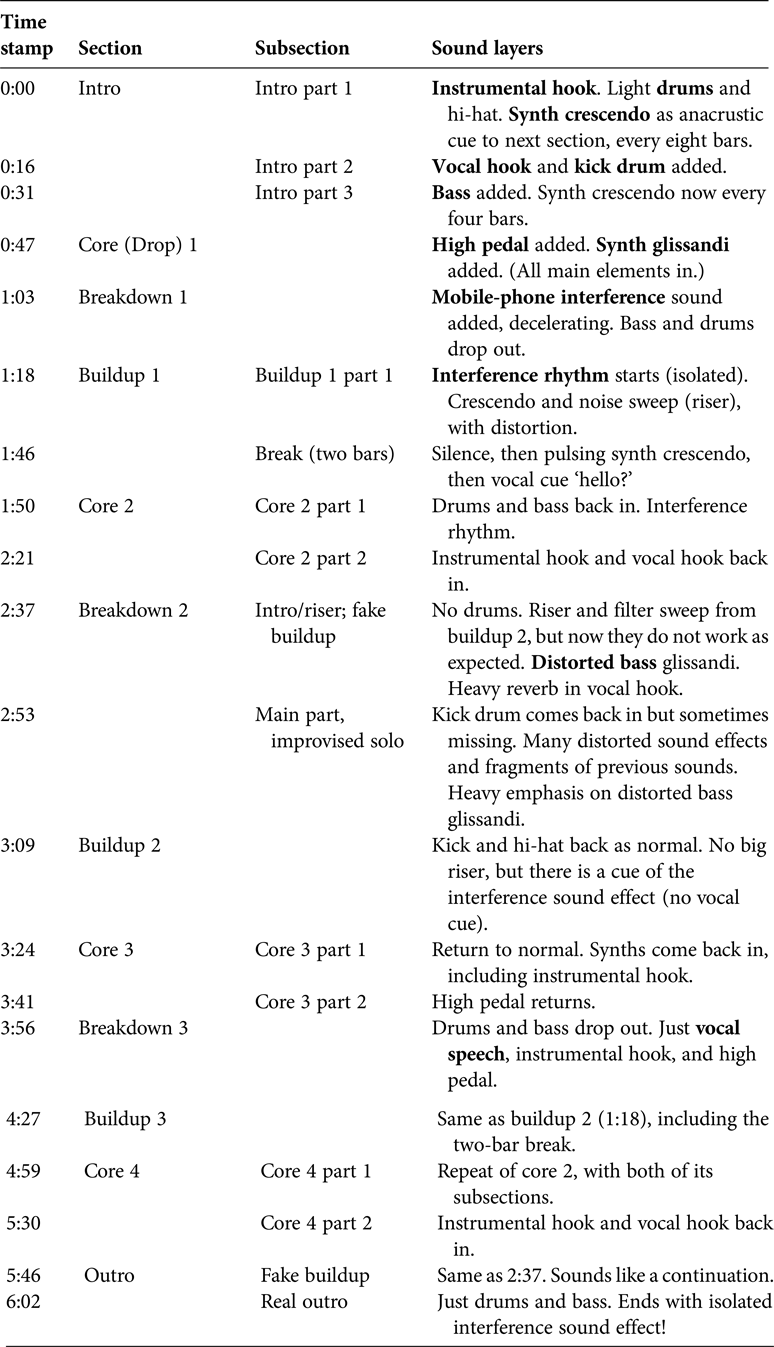

Table 1 Form chart of ‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki (Reference Munki2017)

Note: Bold font indicates the initial appearance of a sound layer.

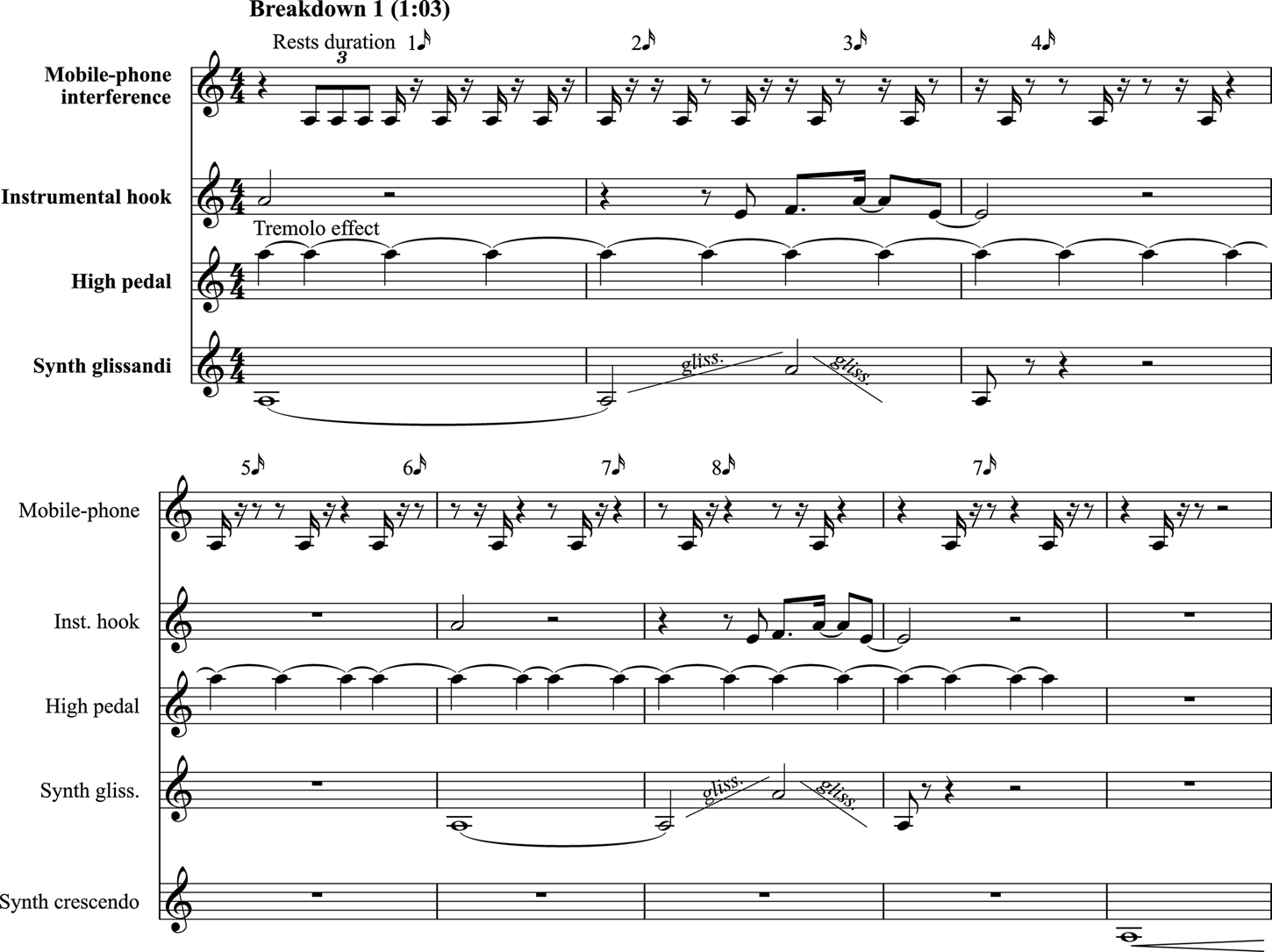

A transcription of breakdown 1 is shown in Example 2. This section uses many of the previously mentioned techniques of disorientation. For instance, although the sound layers I labelled as instrumental hook, high pedal, and synth glissandi continue their patterns from the previous section, the drums and bass are removed. Without the drums explicitly presenting each beat, the metre is less obvious. Though the pitched layers do clearly maintain hypermetre, they do not clearly articulate the tactus pulse. Instead, the beat is only suggested through continuous volume changes (with the tremolo effect) in the high pedal point. Other continuous processes are heard in the lower synth's glissandi. This is significant because continuous processes are inherently unstable, with constant change, and they contribute to an overall sense of instability in this breakdown section.

Example 2 Transcription of breakdown 1 in ‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki (Reference Munki2017).

Additionally, this section introduces a new, distinctive sound that I interpret as representative of mobile-phone interference. This interpretation is partially informed by the lyrical narrative in breakdown 3 and partially informed by my identification of the sound as a common one in internet sound banks, listed as a mobile-phone interference sound effect.Footnote 40 When this sound is first introduced in breakdown 1, it quickly decelerates, with its articulations becoming farther and farther apart as shown above the staff in Example 2.Footnote 41 It is as if the sound is ‘breaking up’. This process and the distinctive, new timbre associated with it, help disorient dancers from the metre. Even if listeners use ‘virtual reference structures’ to internally maintain a sense of the beat,Footnote 42 it is hard to keep track of the rhythm in the interference sound because of the increasing space between notes. After eight bars of deceleration, the sound re-establishes itself at the start of the following buildup section with what will become its characteristic rhythmic pattern in the track (‘interference rhythm’ in Table 1).

After a clear buildup and drop sequence, breakdown 2 starts at 2:37. This breakdown section is unusual in that there is not a prolonged lull in sonic intensity. However, there are some other signifiers of breakdown sections here. The drums drop out entirely for the first eight bars (first subsection), while the vocal and instrumental hooks continue. A new timbre is introduced, which is a harsh, distorted bass that slides up an octave every two bars. Additionally, there is a riser, which sounds like the revving up of an engine, and this leads into a high hissing sound. The riser signifies a buildup section, especially since it has been heard before at 1:36 during buildup 1. On the other hand, the absent drums and new timbre signify a breakdown section, so there are conflicting musical messages here.

The reason why I have decided to label this section breakdown 2, despite the mixed messages, is that the aesthetic of disorientation continues in the second subsection, starting at 2:53, which is the main part of breakdown 2. A transcription of this subsection is shown in Example 3. Now, instead of a lack of sonic intensity and unclear metric pulses, the disorientation is primarily caused by unpredictability, in what sounds like an improvised DJ solo, as if Chunda Munki were ‘playing around’ during a live performance. Although the drums do return here, they are sometimes missing, such as on the expected downbeat at 2:53 (see Example 3). The late drum entrance probably puts many dancers out of step in live situations. Drums are also absent for entire bars at 2:55 and 3:07 (bb. 2 and 8 in Example 3). There is emphasis on the loud, ‘distorted bass’, and the syncopation in the ‘fat bass’ conflicts with the metric pulse. Both bass sounds have short fragmented lines that contribute to the improvisatory feel.

Example 3 Transcription of the main part of breakdown 2 (starting at 2:53) in ‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki (Reference Munki2017).

Next comes another buildup section leading into core 3, although it is not as clear or obvious as the buildup leading into core 2. The third drop is not as intense as the second and fourth ones because its preceding buildup section has no significant riser and therefore less tension. The fourth and final drop is the climax of the track though, and it comes after the most obviously disorienting breakdown in the piece.

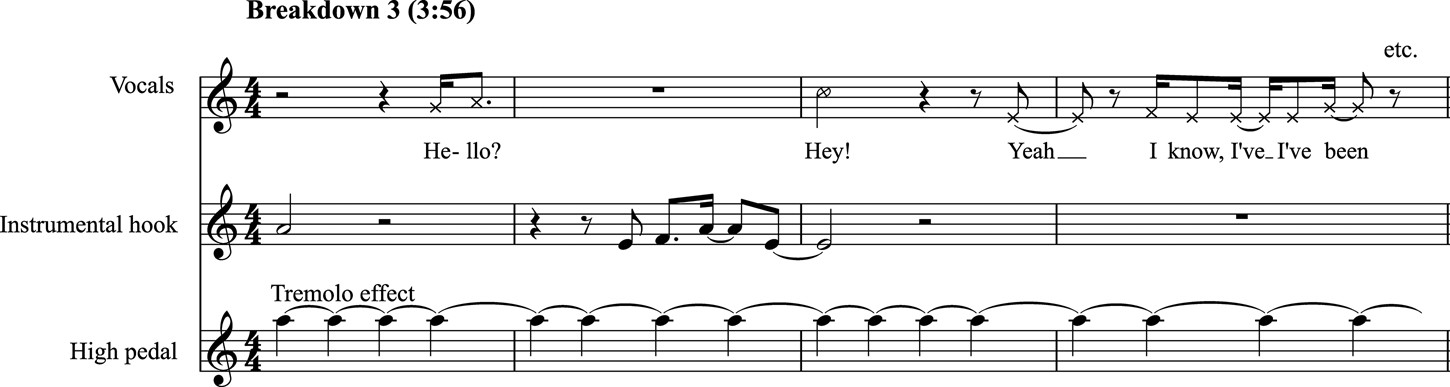

Breakdown 1 featured the new mobile-phone interference sound, then breakdown 2 featured two bass sounds, and breakdown 3 features a speaking voice. The sound of this voice has been heard before, but now it is foregrounded in a stripped-down texture. As shown in Example 4, there are only three perceived sound layers: the instrumental hook, the high pedal, and the vocal part, which has the echo effect applied to it.

Example 4 Transcription of the first part of breakdown 3 in ‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki (Reference Munki2017).

Previously, the only vocal words spoken in the track were ‘just something I got’, with a repeated rhythm. This is the vocal hook that is by now familiar to listeners, and it was used effectively as a cue to the second drop. In this final breakdown section, however, the speaking voice puts the words ‘just something I got’ into a larger context, providing a narrative that is central to the hermeneutics of the piece. The one-sided speech is presumably from a phone call when one person ‘breaks up’ with a romantic partner.

There are both musical and narrative associations between breakdown 1 and breakdown 3. In both sections, the foregrounded sound layer is accompanied by the instrumental hook and the high pedal point with tremolo effect. Narratively, the interference sound itself breaks up in breakdown 1, and the relationship breaks up (through vocal speech) in breakdown 3. The interference sound effect being used for a repetitive ‘interference rhythm’ throughout much of the track could be interpreted as sonic interference in most of the couple's communications. This would allow the partner who is being broken up with to remain in denial. It would also mean that the deceleration of the interference sound in breakdown 1 signals clearer phone reception and an impending forced confrontation with the troubles of the relationship. The relationship troubles are only fully clear in breakdown 3, when there is no interference sound.

This track demonstrates that breakdown sections are times within the structure of an EDM track or performance that can be useful for performers in communicating meaning to the audience. The usual lack of drums and other instruments associated with high-energy levels disorients listeners from a focus on the beat and their bodies. In this case, that allows Chunda Munki to present a story that gives emotional meaning to the piece. However, other musicians can take tracks and remix them to create different narratives.

For example, the remix of ‘Interferance’ by Brazilian DJ Rrotik (released by Chunda Munki on the 2017 album Interference: The Remixes) makes much less use of the interference sound effect. It does feature the vocal speech about breaking up the relationship, but only the first part of it is heard during the short breakdown section. The second half of the speech is harder to hear because other sounds crescendo as part of a buildup section. These other sounds eventually overtake the voice, which is muffled and fragmented as it says the crucial words: ‘I love him.’ This is followed by a break with a descending chromatic scale and an ascending wind-whistle sound, before the cue word ‘goodbye’ and the final drop.Footnote 43 One interpretation of this remix would be that the words of the vocal speech are not clearly understood because they are drowned out by other thoughts of the person receiving them. In this version, it seems as if the cause of interference in the couple's communications is not mobile-phone coverage, but the mental state of the one receiving the speech.

Breakdowns in one of Chunda Munki's live performances

So far this article has focused on the aesthetic of disorientation in published EDM tracks. However, the aesthetic of disorientation in breakdown sections is an important part of live performances too, perhaps even more acutely than on polished tracks. One good example is Chunda Munki's live performance at the 2019 ‘Get Real’ festival in Cape Town, South Africa.Footnote 44

During a performance of the track ‘Vibrate’ by Morelia (feat. DANI), Chunda Munki breaks the track down to nothing but a two-word speech sample (‘make you’ from ‘gonna make you vibrate’) and repeats this over and over. At first the sample fits within the prevailing metre of the track, since the rhythm is two beat divisions (quavers) that stay within the tempo. The disorientation level is relatively low, even though there are no other sound layers such as drums that can help dancers keep a beat. Soon Chunda Munki accelerates the sample. The pronunciation of the words seems to change, then the words become indistinguishable, and eventually the sound transforms into an ascending pitch. This gradual acceleration takes place from 0:15 to 0:41 in the linked video of the performance. It creates an aesthetic of tension since it is not clear when the regular elements of the track will come back, and there is disorientation since there are no reference structures that maintain the metre or the tonal centre. Chunda Munki then holds the audience in a heightened state of tension by playing with the transformed sample sound, soon decelerating it and then finally adding the finishing word ‘vibrate’ before adding the track's bass line, then drums back into the mix.

The body language of the audience, and of Chunda Munki himself, shows the importance of this section that provides a break from the typical dance beats. At 0:19, Chunda Munki is shown mimicking the music with his body language and looking out towards the audience. In festival settings, breakdown sections provide a good chance for a performer to communicate with their audience, since audience members generally notice that the beat is unclear or has been taken away, and one thing they can do is look up to the stage. In this portion of the performance some audience members are shown not moving, while others try to keep up with the musical acceleration in their body movements. When the acceleration stops, there is not much movement among audience members. They have been disoriented from the metre and other regular elements of the track. When the bass comes back (at 0:52), and especially when the drums re-enter and the beat becomes clear again (at 0:56), there is much more body movement. The dancers appreciate the clear beat and bass line returning, and the aesthetic of disorientation in the breakdown section plays an important role in this musical process of tension and release.

Throughout the performance, Chunda Munki does similar musical moves in breakdown sections, with absent drums and continuous processes in pitch, rhythm, volume, and/or timbre, creating an aesthetic of disorientation. For example, at 16:44 the drums drop out, then there are continuous changes in pitch and timbre before a drop at 17:15. In this case, the breakdown section of the performance is also a transition between recognizable tracks. Another breakdown section soon follows at 18:01. This one features many more continuous changes, before a few seconds of silence, then a brass cue, then a drop at 18:55. Chunda Munki is seen communicating with the audience during the cue and at the drop, demonstrating how to dance.

The video analysed in this section demonstrates the role of breakdown sections for at least one live performance at an EDM festival. It also provides an indication of the aesthetics of breakdown sections generally, even if they are more frequent and obvious in this performance than many others.Footnote 45

‘Move’ by Cassy (Reference Cassy2016)

For another analytical case study, this section discusses the track ‘Move’ by Cassy (aka Catherine Britton). She is a British-born, Austrian-raised performer who has held residencies at prestigious clubs throughout Europe.Footnote 46 Although she is more associated with the underground club scene than the mainstream festival circuit, she does perform at festivals too.Footnote 47 Her original music is known for blending elements of house and techno, as well as incorporating rhythms and timbres from jazz or funk music. Therefore, much of her music can be described as ‘tech house’ or ‘deep house’.Footnote 48 As a child in Austria, she was exposed to a wide variety of music from a young age, and she has cited interactions with jazz musicians as being highly influential to her musical style.Footnote 49 Today she is still performing and touring, while also being a proud mother and managing the label she founded, Kwench Records.Footnote 50 Given Cassy's musical style of fusion, it is noteworthy that the label focuses on collaborations and that it was created by Cassy ‘to blur the lines between commercial and underground, house and techno, fun and top-notch quality’.Footnote 51

Cassy has released three main albums featuring her music so far: Donna (Reference Cassy2016), Cbm 1, and Cbm 2 (both released in 2021). Many of their tracks do not have clearly demarcated breakdown sections, but one track that does is ‘Move’ from Donna. This first album of Cassy's was produced alongside King Britt, who is well known for his work in trip hop. The album mostly consists of tracks that are house, techno, or somewhere in between, but many lack the clear breakdown→buildup→drop sequences that characterize festival types of house and trance music.Footnote 52 There are also some tracks that are slower and more ambient, as well as some that are best described as Latin jazz with an electronic twist. It is noteworthy that Cassy's singing voice is prominent in most of the tracks. She has said that the album is about emotions and relationships and that most men she knows in the EDM world would shy away from such open emotional expression.Footnote 53 One track on the album that exemplifies this is her cover of Prince's ‘Strange Relationship’.

The track that will be analysed here is ‘Move’, which is in the genre of deep house and features a strongly disorienting breakdown section. A form chart for the track is shown in Table 2. Although the formal structure of the track is fairly clear, some aspects of it are less obvious than they would typically be in most festival-house tracks. Specifically, the drops at the beginnings of the core sections have less intense climaxes. Another thing that makes this track different from most festival EDM is how frequent the subtle textural changes are, particularly in core 1.

Table 2 Form chart for ‘Move’ by Cassy (Reference Cassy2016)

Note: Bold font indicates the initial appearance of a sound layer.

As shown in Table 2, the breakdown section starts with a thin texture of only a high string pedal and a synthesized voice. Although both have been heard previously in the track, this is the first time that they are isolated and sounded prominently. At this point, the removal of now familiar elements (such as the bass line, syncopated synth, and ‘I like to move’ riff) creates a sense of instability.

The complete absence of the drums, combined with a static string note and unclear articulation in the voice, make any sense of rhythm and metre hard to discern in the first part of the breakdown. This likely causes dancers to stop moving their bodies when listening, since there are no metrical or hypermetrical cues given. The situation is like the one Joe Smooth described to me (mentioned earlier) when people can stop and take pictures or check their messages.

Additionally, the string pedal and synthesized voice do not create clear tonal stability. The voice loop has unclear rhythm and continuous pitch movements, sliding between members of a second-inversion tonic triad (in the key of D♯ or E♭ minor). Meanwhile, the string pedal holds scale degree 5. Although the constant presence of one note is stable, the use of scale degree 5 produces a sense of openness compared with scale degree 1.

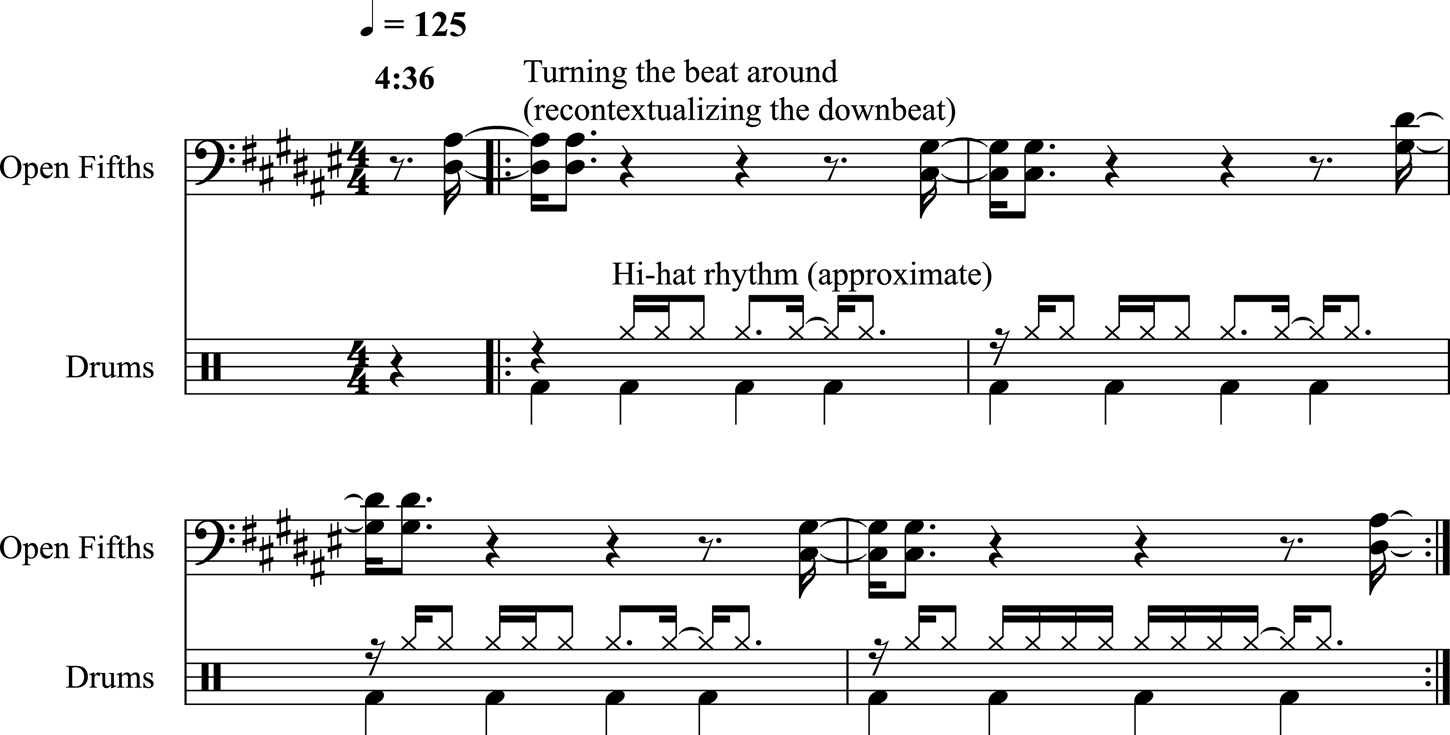

The second part of the breakdown (4:13–4:35) introduces a new element not previously heard in the track. As discussed earlier, this is a common technique in house breakdown sections, and the unfamiliarity of the sound layer helps contribute to the aesthetic of disorientation crucial to this part of the track's structure. In this case, the newly introduced sound layer is a four-bar pattern of ‘open fifths’. Both the rhythm and the timbre of this sound layer are new to the track, although the timbre is seemingly a mellower version of the ‘syncopated synth’ sound.

When the open-fifths loop first comes in it reintroduces some metrical stability to the track, in the absence of drums. This is shown in Example 5, which demonstrates the rhythm of the open-fifths loop as it will likely be perceived.Footnote 54 It sounds like quavers on the downbeat of each bar. Even though reverb makes the notes last longer than is written here, the articulation and rhythm are still clear, and this generates a clear metre for listeners.

Example 5 The perceived metre of the ‘open fifths’ element when it first comes in at 4:13 (the second part of the breakdown) in ‘Move’ by Cassy (Reference Cassy2016).

However, when the kick drum and hi-hat finally re-enter the texture at 4:36, this metric interpretation of the open-fifths loop is revealed to be false. Or, to put it another way, the metric interpretation of the open fifths changes at 4:36, from the way it is written in Example 5 to the way it is written in Example 6. This is an instance of what Mark Butler calls ‘turning the beat around’Footnote 55 and it is only possible here because of how the breakdown section worked. Specifically, the metric switch could only be accomplished because the two other elements in the breakdown (the high string pedal and synthesized voice) were not metrically stable enough to keep the beat from the first core going.

Example 6 The ‘open fifths’ element and drums at the start of buildup 2 (4:36) in ‘Move’ by Cassy (Reference Cassy2016).

If one were to have a metronome on during core 1 and into the breakdown, the open fifths would sound syncopated, as they are written in Example 6. In other words, they are likely written as syncopated in the composer's DAW file, but only interpreted as syncopated by listeners when the kick drum comes back at the start of buildup 2. This means that the breakdown section disorients listeners from the ‘true’ or prevailing metre of the piece.

As the track continues, the open-fifths loop stays as one of the more prominent elements in the mix. This is typical for new elements that were introduced in breakdown sections, especially in house music. The now-clear syncopated nature of the open fifths contributes to the deep-house groove as it combines with other syncopated elements such as the hi-hat, syncopated synth, and bass line. These syncopated sounds work well in counterpoint with the kick drum and with the ‘I like to move’ riff that has a simple rhythm, emphasizing beats one and three.

Even though ‘Move’ is not a typical festival-house track, the breakdown plays a crucial role in the aesthetic experience of the piece. It disorients listeners from what they have heard previously and encourages dancers to physically rest. The newly introduced open-fifths loop gives listeners something else to focus on, and in the context of a thin texture with some unstable elements, disorients them from the prevailing metre of the piece. When the open fifths later fit into their ‘proper place’ within a fuller texture, they can be appreciated more fully as part of the track's groove.

‘Need2Freek’ by Walker & Royce (2020)

For a final primary case study, this section analyses another track that has a clear aesthetic of disorientation in its breakdown: ‘Need2Freek’ by Walker & Royce. They are an American duo (Samuel Walker and Gavin Royce) currently based out of Los Angeles.Footnote 56 They are known for their deep-house music, but ‘Need2Freek’ is a tech-house track, released as a single in December 2020. As with ‘Interferance’ by Chunda Munki, the breakdown section is important to the narrative meaning of the piece. In this case, my interpretation is that the speaking voices represent android characters that dance incessantly and (as the title says) ‘need to freak’.

The word ‘freak’ has several different meanings and connotations. It can be used as a noun to mean something or someone unusual and strange, usually with a negative connotation. As a verb, it can be used to indicate someone being scared, shocked, or losing control of themselves, as in ‘I'm freaking out.’ It could also mean having sex, doing drugs, hallucinating, or dancing, in ways that are wild and associated with losing control. According to the OED, the phrase ‘get your freak on’ could mean engaging in sexual activity or dancing, but in both cases in a way that is uninhibited.Footnote 57 One particular song that has helped establish a connection between the word ‘freak’ and dancing is ‘Le Freak’ by Chic (1978). It is noteworthy that when ‘Need2Freek’ was released in late 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made many social activities difficult and risky, which could be why the song expresses such strong desire. This same desire to move more freely during the pandemic was expressed by Beyoncé regarding the making of her album Renaissance (2022), which is a tribute to early Chicago house music and its importance in Black and Queer culture.Footnote 58

The cover art for ‘Need2Freek’ (Figure 1) shows a group of humanoid characters that have been mutated or deformed in a variety of ways, chasing one more normal-looking human. Presumably the group of mutants are ‘freaks’ and perhaps they are chasing down the human to get them to dance. In addition to the cover art, the musical structure of the breakdown section and its aesthetic of disorientation lead me to an interpretation of the track that includes android or cyborg characters.

Figure 1 (Colour online) Cover art for the single ‘Need2Freek’ by Walker & Royce (2020).

A form chart for the track is shown in Table 3. It has three cores, each preceded by anacrustic filter sweeps and drum fills. There are only thirty seconds before the first core section starts, and fifteen seconds between the end of core 1 and the beginning of core 2, but there is a full minute between the end of core 2 and the beginning of core 3. This minute includes a two-part breakdown section as well as a buildup.

Table 3 Form chart for ‘Need2Freek’ by Walker & Royce (2020)

Note: Bold font indicates the initial appearance of a sound layer.

The first part of the breakdown participates in an aesthetic of disorientation in two ways. First, multiple sound layers that have been important throughout the track so far drop out for the first time. These include the kick drum, bass line, and synth chords. Second, this breakdown does not introduce any new distinct sound layers, but rather it transforms ones previously heard in the track. Specifically in this first part of the breakdown, the vocal 2 speech sample is highlighted and transformed.

My interpretation of the vocal 2 layer is that it represents something that is not human (either an android or a cyborg). Just before and during core 2 it says: ‘I will never stop dancing, never, ‘cause I come from the other side’. In the first part of the breakdown section, it has a different rhythm from its previous renditions; now the words ‘I will never’ are slower and more quantized. Also, on the word ‘stop’ it accelerates for the first time, to a speed that is beyond the capabilities of a human voice. This can be seen in the spectrogram in Figure 2. By the end of the acceleration, the voice sounds like a mere (non-human) instrument.

Figure 2 (Colour online) Spectrogram of the first part of the breakdown (2:32–2:47) in ‘Need2Freek’ by Walker & Royce (2020). The acceleration in vocal 2 is shown by the low white lines getting closer and closer together during 2:34–2:39 and 2:42–2:47.

The glitch sound effects throughout much of this track and particularly the breakdown also contribute to an aesthetic of mechanization. They seem as if they were randomly generated by a computer. Furthermore, in the first part of the breakdown there is a sharp riser sound that was probably generated with a sawtooth wave. Like the other elements in this subsection, it has a timbre that is associated with robotics and computers.

The second part of the breakdown continues to have clear metre and hypermetre, but it starts with a very thin texture, only featuring vocals and synth chords. Again, a vocal 2 sample that was previously heard returns, but in a transformed way. This time it features the words ‘In my flat. In my class. With my friend. Around the world.’ The vocal speech sample is now two octaves lower than it was originally, and it has a distorted, seemingly unnatural timbre. These changes, combined with the sudden texture change, contribute to a disorienting aesthetic.

As the second part of the breakdown section continues, the vocal hook of the piece (‘I need to freak’) fades in, along with snare-claps on the backbeats.Footnote 59 In the second half of this subsection, the instrumental sounds also play a part in the aesthetic of disorientation with their continuous, unpredictable changes in pitch and timbre. The pitch and timbre changes are subtle, like variations in tuning, and were probably controlled with a wheel, knob, or slider. They occur during dissonant chords that are held for several beats at a time. The instability of the continuous processes and the dissonance in the harmonies both contribute to the disorienting aesthetic. At 3:18, the track subtly slips into a buildup section, which leads into the final drop.

Throughout this track there is tension between human and non-human representations of the voices, specifically the vocal 2 sound layer that represents a speaking character. On the one hand, we can relate to the voice talking about dancing ‘In my flat, in my class, with my friend, around the world.’ On the other hand, the voice sounds very robotic, and it declares ‘I will never stop dancing, ’cause I come from the other side’. Acceleration communicates that this character can move incessantly and it has no need to breathe. Additionally, the vocal 1 part repeats its pattern many times throughout the track, simply stating ‘I need to freak.’ These techniques play into the multiple meanings of the word ‘freak’ and a common trope of androids wanting or needing to have sex incessantly.

Even though there is tension between human and machine ideas throughout the track, it is the breakdown section that presents narrative meanings and extra-musical associations most clearly. As we have seen, this is a common feature of breakdown sections in festival-house music. The music video for this track also imbues the breakdown section with special meaning.Footnote 60 The entire video uses images and colours associated with psychedelic hallucinations, but the breakdown section (2:03–2:49 in the video) has visuals that are particularly disorienting. In the first part of the breakdown (2:03–2:18), a collage of images comes at the viewer, including hands that reach out as if to say stop, despite the lyrics saying ‘I will never stop.’ The acceleration in the voice part on ‘stop’ is paralleled by a sharp increase in visual changes before the screen cuts to plain black at 2:19. For the second part of the breakdown at 2:21, the characters on screen resume their dancing but the visuals are less busy than they were before in the track, reflecting the thin texture of the music.

To further emphasize how the breakdown section is associated with disorientation from the prevailing dance beat of the piece, it is interesting to consider the body language of Royce in a live performance of ‘Need2Freek’.Footnote 61 This performance was at the end of a short set for a virtual ‘rave-a-thon’ on 31 October 2020 (just over a month before the track was officially released). It was part of a Halloween-themed event that featured a virtual audience because of the pandemic. There are other performers on stage, but no in-person audience that is reacting spontaneously to the music.Footnote 62

The track starts around 34:53 in the video of the entire set, and the breakdown begins at 38:26. The breakdown is longer in this live version. Specifically, the first subsection is twice as long as it is in the official track, and it features more manipulative ‘tweaks’ to the sounds such as a clear use of the echo effect. It starts with the kick drum remaining in the texture, but there is still a drop-off in energy because the higher drums cut out, and the texture only features the kick drum with vocal 2. At first Royce continues moving to the beat of the kick drum, but then his body moves with the metrical dissonance of the voice on the repeated word ‘stop’, and finally his body stops moving to any kind of beat. This visually shows how the breakdown disorients listeners from the metre of the track. Royce also stops moving to the beat when he alters the sounds with effects processors and adds glitch sound effects (38:47–38:57).

At the start of the second subsection of the breakdown (38:57), Royce puts his hands out to the side, palms down, indicating the sudden change in texture that leaves only the synth chords in the mix. His hands move with the rhythm of the synth chords. In the last part of the breakdown (39:27), the kick drum is still out of the texture, but the snare-claps have returned on the backbeats, and Royce is once again moving to the clear beat, in anticipation for the final drop at 39:58. The body movements of dancers in a live audience would presumably be similar to his movements in this performance, especially since, as previously discussed, dancers often look up to the stage when the beat stops in breakdown sections.

Conclusion

This article has discussed several examples of breakdown sections in contemporary house tracks often used at EDM festivals, noting how they have an aesthetic of disorientation that contrasts with the growth in buildup sections and the repetition in core sections. Common techniques used in breakdown sections are the removal of the kick drum and perhaps all clear references to the beat, the introduction of a new element in the track or new sound effects, the use of metrical dissonance, a lack of clearly articulated notes, and the use of continuous processes such as glissandi. This concluding section of the article will further discuss why producers and performers might use these techniques to create an aesthetic of disorientation in breakdowns, and what purposes they serve from the perspective of performers as well as dancers.

Earlier in the article it was said that the disorientation in breakdown sections can be both physical and psychological for dancers. This means that the changes in a breakdown section can make dancers ‘lose their place’ in terms of their psychological perception of the metre and their bodily representation of or connection with the metre. In breakdown sections, often the metre is unclear or less clear than it previously was, and in live situations this can cause listeners to stop dancing or dance in different ways that are usually less energetic, as described by the producers I interviewed. When the rhythm and metre are unclear and there are new or transformed sounds to focus on, it is hard for dancers to physically engage with the music. Also, there are often unstable continuous processes that can create a sense of confusion for dancers.

The breakdown provides a natural point of rest for tired bodies and allows them to rejuvenate before moving more fervently in buildup and core sections. Throughout a long set, these points of rest can help people maintain stamina so they can stay out for an entire night. Tyler Marenyi told me he thinks about this when designing concert sets, and for sets that are longer than an hour he consciously adds more breakdown sections.Footnote 63 If someone were in need of a prolonged break, a breakdown section would be a clear time when they could leave and do something else. For those that stay on the dance floor, breakdowns also allow opportunities for social interaction with other dancers, who often communicate with body language.

Musically, one purpose of breakdown sections is to provide a necessary contrast with other sections that precede and follow them when the energy level of the track is high. Producers Armin van Buuren and Rick Snoman have both described experiencing EDM as like riding emotional waves, and the lull in energy during breakdown sections as an important part of that.Footnote 64 Empirical studies such as the one by Solberg and Jensenius mentioned earlier show that dancers experience EDM with psychological ups-and-downs, finding more pleasure in buildup-drop sequences, and responding with more body movement during those sections, as opposed to breakdowns.Footnote 65 Emotional waves happen when listening to festival EDM in particular not only because of the intense climaxes but also because of the disorienting, low-energy parts that precede them. The joys of stability, of being firmly grounded, and of being synchronized with the beat and with other bodies are amplified after moments of disorientation, tension, and instability.

One track that is uniquely well suited to discussing the purposes of breakdown sections is ‘This is the Hook’ by BSOD, released as a promo single in 2006 and later on deadmau5's album At Play (2008).Footnote 66 This self-referential track has lyrics that narrate the different formal sections and musical components of the track by describing them as they happen. The first breakdown has the following lyrics: ‘Now it is time for the breakdown. The breakdown allows the track to breathe and break the repetition. Let's filter the hi-hat. Let's filter the chords. Let's filter the bass. I like the filters. I like the grooves, but I digress.’

As the lyrics state, the breakdown provides a necessary contrast from the other sections, allowing the track to ‘breathe’ and have some time with less intensity, so that the high energy of the core sections can be appreciated more.

The second breakdown of ‘This is the Hook’ references another purpose of breakdown sections, from the perspective of a performer. As Mark Butler has noted, in live settings breakdowns encourage interaction between the performer and the dancers.Footnote 67 The lyrics describing the second breakdown of ‘This is the Hook’ from the DJ's point of view say: ‘Now for the quiet part. Let's break it down to a kick drum. Now you should notice the dance floor is reacting. Look up from your decks. Look at the audience. It is important to show that you are alive.’Footnote 68

When an EDM festival audience is disoriented from the primary beat and/or grooves of a track, they can look up at the stage, focusing on something other than their own bodies. This also means that if there is a message or theme that the performer wants to communicate, the breakdown is a good time to do it. For example, the way in which the words were spoken in the breakdown sections of ‘Interferance’ and ‘Need2Freek’ is crucial to the hermeneutics of those pieces. In this respect the disorientation is a tool, since it can stop dancers from moving and break their entrainment, inviting them to think about what has changed in the music. Often, climactic drops are preceded by ‘one-liners’ as cues that communicate the primary meaning of a track, but sometimes more explanation of the one-liner is given in breakdown sections. If an EDM piece has lyrics, it is likely they will be mostly heard in the breakdown section(s), so as not to distract from the beat and instrumental grooves in other sections. Even in ‘This is the Hook’, most of the lyrics are in the breakdown sections and the other sections only have short, repeated lines.

Further study of breakdowns and the techniques they frequently use would be valuable for exploring how an aesthetic of disorientation is communicated, and to what degree it is, in various tracks and performances. It would also be useful to do further comparisons between breakdown sections in different EDM genres, such as dubstep or drum & bass, and to study how breakdowns have evolved over time in more detail. Further research on the reactions of dancers to breakdown sections in different settings would be another useful way to continue the discourse on this topic.

This article has discussed some aspects of how and why disorientation is used as an aesthetic strategy in breakdown sections of festival-house tracks and performances. Through my analysis of interviews and musical examples, I hope to have shown that breakdown sections, and their aesthetic of disorientation, are crucially important to the experience of this repertoire.