In 1960 Robert Brentano published his essay on “The Bishops’ Books of Città di Castello” in Traditio volume XVI. In it he wrote of the “lost treasure” he discovered on the upper reaches of the Tiber in the episcopal archives of “a pleasantly undisturbed provincial cathedral town in northern Umbria.” That treasure was the nine great codices containing the atti della curia vescovile.Footnote 1 Brentano's description was lyrical, evoking all the pleasures of discovery and of bemusement in leafing through miscellanies, for the bishops’ books of Città di Castello were bound only in the modern era and seemingly without much attention to chronology. Gatherings from the early thirteenth century rub up against ones from the fifteenth, and the acts of bishops who lived decades apart mingled together peaceably. Like many medieval volumes called “registers,” these originated as loose parchment booklets, usually comprised of four large sheets folded and nested together to form eight-folio gatherings. The notaries who drew them up called them quaterni, and some numbered them on the outer-front folio allowing the chronology-obsessed among us to try to reconstruct their medieval arrangement.Footnote 2 Brentano seemingly took their temporally chaotic organization in stride and proceeded to offer his readers not only an introduction to the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century bishops of the see, but also a rough finding aid to the collection that has guided researchers for decades.Footnote 3

Still more important were his subsequent observations about episcopal registers in his classic comparative history, Two Churches: England and Italy in the Thirteenth Century.Footnote 4 In the chapter entitled “The Written Church,” he contrasted the ubiquity of bishops’ registers in the thirteenth-century English church and their extreme rarity in the Italian church of the same period. He indicated, in fact, that the only Italian see for which bishops’ registers survive was that of the tiny Umbrian town of Città di Castello.Footnote 5 Brentano perhaps emphasized the uniqueness of this small Umbrian city's episcopal registers to ensure that Italian scholars from other cities would scour their archives and prove him wrong — which, of course, they did. Many of their discoveries were presented at a conference in 2000, the proceedings of which were subsequently published in the 2003 Italia Sacra volume I Registri vescovili dell'Italia settentrionale. Footnote 6 Directly responding to “The Written Church,” contributors described and analyzed important series of episcopal registers at Como, Mantua, Padua, Trent, Sabiona-Bressanone, and Aquileia. They also established useful distinctions between different types of episcopal registers: books of rights (libri iurium), registers of episcopal notaries, protocols of notarial imbreviature, fiscal records, chancery acts, and the Traditionsbücher (libri traditionum) peculiar to the regions of the Alto Adige and Bavaria.Footnote 7 Although Città di Castello, clearly, was not the only Italian see with surviving episcopal registers, my eminent predecessor's intuition that there was an important historical problem in the city's “bishops’ books” was prescient and the comparative approach he cultivated is still an essential methodology in understanding the significance of the archival evidence.

Brentano framed the historical significance of the bishops’ books of Città di Castello in terms of what they can tell us about ecclesiastical governance. They are definitely rich sources for this topic which continues to be relevant, especially within debates over lordship and changes in the exercise of power over the central and later Middle Ages.Footnote 8 But they are also important evidence for a broader set of changes in medieval documentary practices that Jean-Claude Maire Vigueur has dubbed the “documentary revolution.”Footnote 9 He articulated this concept in an appreciative review of Paolo Cammarosano's Italia medievale: Struttura e geografia delle fonti scritte.Footnote 10 Maire Vigueur rightly pointed out that Cammarosano accomplished much more in this volume than a simple guide to the sources of Italian medieval history: he in fact reconstructed the documentary landscape (paysage documentaire) of the peninsula and traced key changes in it across the central and later Middle Ages, highlighting the conditions driving the production and conservation of documents. In brief, Cammarosano sketched a long period of ecclesiastical hegemony in documentary production and conservation extending from late antiquity to the eleventh century and then, from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, a quantitative explosion in the number of documents produced and a rapid multiplication of new typologies and forms of documentation as the Norman-Hohenstaufen kingdom developed in the south and the communes emerged in the north. These new systems of power broke ecclesiastical textual dominance and initiated fundamental changes in the production and conservation of documents. Cammarosano himself acknowledged and discussed at length the continuing role of ecclesiastical institutions in documentary production and innovation, underscoring that “the change of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries was general, affecting the forms of private texts and of public documents, those of historical narrative and the same traditional forms of ecclesiastical institutions.”Footnote 11 In characterizing these changes as revolutionary, however, Maire Vigueur demoted the roles of both ecclesiastical institutions and the Norman-Hohenstaufen monarchy in the south in order to give the communal regimes of the north the “decisive” role in effecting the révolution documentaire. He highlighted in particular the emergence of the new executive office of podestà, which encouraged notaries to elaborate new types of documents and systems to conserve them, and the rise of the more radical solution to the violent power of the old consular nobility, the popolo, which developed systems of registers across the many proliferating offices, councils, and bureaus that solidified the dominance of this political movement. It is the rapid changes and exponential increase in written instruments under the popolo regimes of the second half of the thirteenth century that moved Maire Vigueur to declare a “revolution.”Footnote 12 And it is this framing of the “documentary revolution,” emphasizing the lay protagonists of the northern communes — communal officials, but especially the notaries who created the documents and new systems of organizing them — that has generated the greatest interest.Footnote 13

But were the communes the innovators? Did they first develop the registers that are the primary evidence of the “documentary revolution”? Or the systems of organized groupings of quaterni, of parchment booklets, that are bound together to form registers? Who first made the leap from single-sheet loose parchments to books or booklets? Città di Castello and its archives offer an ideal laboratory for answering these questions: multiple series of early registers survive here. In addition to the bishops’ books that enthralled Robert Brentano, there are registers surviving in the archives of both the cathedral chapter and the commune. In fact, if we look at the entire landscape of documentary change in this one city, the communal government appears to have been the last of these three institutions, not the first, to produce registers.

The Commune

The communal government's earliest documentation from 1163 consists of individual loose parchment documents, mostly privileges, donations, oaths of alliance, and judicial acts. From a fifteenth-century description, we know these parchments were kept “nella capsa de le quattro chiave,” the chest of the four keys, that is, a high-security lockbox requiring four different keys to open it.Footnote 14 The chest also contained the commune's earliest register: “uno libro nero el quale se chiama ‘el libro del Castello’” or the black book called the book of Castello. Two thirteenth-century codices actually survive, each called the black book or libro nero of the commune, but today denominated Libro Nero I and II. The careful scholarship of Claudia Carini has demonstrated that the second libro nero was more or less a copy made between 1274 and 1277, containing mostly material from the first earlier book with some additions.Footnote 15 That first Libro Nero, a codex of 157 folios, is dated 1205 on its opening page.Footnote 16 This label, however, is deceptive.

As the superb study of the present archivist, Lorenzo Arcaleni, convincingly demonstrates, the Libro Nero I (hereafter, LN1) that we have today is a complex artefact.Footnote 17 The large parchment volume, measuring 440 x 320 x 80 mm (17 x 12.5 x 3 inches), has an eighteenth-century leather binding. It consists of eighty-one large pieces of parchment, each folded at the center, and arranged in gatherings of varying numbers of folios (from two to eight), plus one smaller extraneous parchment (530 x 400 mm; roughly 21 x 16 inches) sewn in. The gatherings also vary in size: up to folio eighty-six, they are more or less the same measurements of the cover, but after that they are all more diminutive, the smallest measuring 330 x 235 mm (13 x 9 1/4 inches). With the exception of the penultimate gathering, only the flesh side of the parchment is written on and there are usually two documents on each flesh-side folio. All the documents concern communal lands, rights, and agreements: the acquisition of lands, payments of communal debts, the exercise of justice, treaties with other communities, acts affirming the submission of powerful elites and their castles, records regarding the collection of dues and other exactions. There are three numerations evident: one medieval in roman numerals centered at the top of the flesh-side folios in a fourteenth-century hand; another eighteenth-century hand in Arabic numerals at the top outer corners of the same folios; and then a recent numeration in the top right corners of each folio in pencil (as opposed to the ink used in the earlier numberings).Footnote 18 Although it is impossible here to relate in detail Arcaleni's careful and insightful analysis of LN1's codicological features, I concur entirely with his conclusions. First, LN1 did not originate as a codex, but as a collection of gatherings, some loose, others perhaps from preexistent volumes for some reason dismembered. Second, these gatherings were first brought together as a unit around 1350 when the medieval numeration was inscribed and, third, this unit underwent one or more subsequent re-managements resulting in the loss of thirteen of the folios from the mid-fourteenth-century organization and the addition of two others.Footnote 19 Technically, one could argue that the LN1 dates to 1350.

But what of the individual gatherings? Can we identify the earliest constituent quaterni in this mid-fourteenth-century collection? When did the commune move beyond single-sheet parchment documents and begin to create and keep records in parchment booklets? Arcaleni's analysis demonstrates that most of the documents collected in LN1 were written by notaries in 1239 (twelve documents), 1242 (twenty-nine documents), 1253 (fifteen documents), 1270 (twenty-five documents), and 1271 (twenty-eight documents). “Synthesizing this data,” Arcaleni concluded, “we can affirm that the most considerable part of the documentary production brought together in the Libro Nero I dates from the period 1221–72, with two peaks in the years 1239–42 and 1270–72, while the number of documents after 1297 is negligible.”Footnote 20 Moreover, he points out that there are within LN1 several “organic” booklets (fascicoli) written by one notary, in one discrete period, consistent in format and in content. The earliest of these booklets was compiled by the notary Iohannes and contains documents dating to 1227–42 recording accords reached with various rural communities defining what they owed to the urban commune. Other early booklets date from 1233–55 (forty-four documents by the notary Bonagratia Çanni recording the submission of rural lords and their castles), 1239–43 (documenting exchanges of houses between the commune and the inhabitants of the destroyed castle of Certalto), and 1242–56 (the opening eight folios of the LN1 redacted by the notary Hugolinus Petri de Canuscio containing varied instruments).Footnote 21 So, the commune of Città di Castello was definitely creating booklets from the late 1220s.

If the earliest “organic” booklet dates to 1227–42, are the earlier documents in the LN1 all later copies? Arcaleni compiled a chronological list of all the documents contained in the LN1 that allows us to answer this question, since he carefully distinguished originals from notary-authenticated copies.Footnote 22 From 1218 on, the documents are overwhelmingly originals with the occasional authenticated copy mixed in. Before 1218, the majority are copies: of the nineteen documents recording acts dated between 1179 and 1216, fifteen are clearly identified as copies by the notaries entering them. Should we take the date of the earliest original document in the LN1 as the date the commune abandoned single-sheet parchments for booklets? These four earliest original documents record two acts from January 1198, and one each from 10 September 1203 and August 1212, and they are concentrated in one section of the LN1, on folios 129v, 130r, and 132v. An analysis of this section of the volume calls into question whether the date of the act was actually the date on which it was written on the parchment folios of the Libro Nero. Indeed, it requires us to delve more deeply into what is meant by an “original” document, and into how the LN1 was compiled and for what purpose.

LN1 is a communal liber iurium, a collection of acts documenting the rights, privileges, treaties, and other things pertaining to the commune.Footnote 23 Generally, these “books” were the products of attempts, the earliest beginning in the twelfth century or in the opening decades of the thirteenth, to systematize the documentation that the commune needed to defend what it claimed as its rights (iura). Pacts with elites and communities in the countryside surrounding a city were typically included as well as treaties with neighboring cities and privileges from sovereigns, particularly the text of the Peace of Constance of 1183, which had granted rights of self-governance to the northern cities of the Lombard League after they had effectively resisted Frederick I Barbarossa's attempt to reimpose imperial rule.Footnote 24 More mundane, but still important, acts, such as purchases or exchanges of property, were also incorporated. Generally, the documents selected for inclusion in these books were not ordered chronologically but instead grouped topographically or thematically in quaterni dedicated to relations with a castle, a city, or an aristocratic lineage. And like Città di Castello's Libro Nero, they were given distinctive names: Reggio Emilia's was the Liber Grossus, Siena's the Caleffo Vecchio, Piacenza's the Registrum Magnum, and Vercelli's the Biscioni.Footnote 25

Generally, two sets of circumstances promoted these efforts at collecting and ordering the commune's important documents. First was the advent of the foreign chief executive known as the podestà.Footnote 26 The earliest of these were imposed by emperors as their representatives, first by Frederick Barbarossa during his mid-twelfth century attempt to reimpose imperial authority in the northern Italian cities, and then by his heirs.Footnote 27 The earliest podestà of Città di Castello appears in 1194–95 in the wake of Emperor Henry VI's successful intervention in 1194 to vindicate his wife Constance's claim to the Norman kingdom of Sicily. The first individual appearing that year in Città di Castello as podestà, Ugolinus de Carzano, is not explicitly identified as the emperor's representative. But in December of 1195 Iacobus Zani, podestà of Città di Castello, confirming an earlier ruling of Ugolinus de Carzano, quondam potestas Civitatis Castelli, declared that he acted “on behalf of the lord emperor and the city's commune.”Footnote 28 Iacobus, in fact, stated that he confirmed the cathedral chapter's rights “having seen the instrument (viso instrumento)” in which the previous podestà awarded possession to the canons. External figures, like this imperially-appointed podestà or the podestà from other Italian cities that communes summoned to act as impartial chief executives, demanded written documents.

Second, neither individuals nor institutions like the commune were paying to have notaries draw up documents on single sheets of parchment for every legal act to which they were a party. From the late twelfth century, notaries in Italy were keeping books of imbreviature, that is, registers of the abbreviated notes (called the imbreviatura or minuta) relating the key legal facts of a transaction or agreement. These notes had to be approved by the parties to the act, and once approved either of the parties could request a mundum, a fully written out version. Since notaries carefully preserved their registers of imbreviature, usually passing them on to their sons or other relatives who took over their business, clients frequently saved money by not having a mundum redacted for routine acts: they knew that if they ended up in litigation they could go back to the notary and pay him to produce the fully written out document. These fully written out munda are what we call “originals.” This system, moreover, allowed clients not only to commission a single mundum on a single piece of parchment, but also to commission notaries to copy out a series of originals relating to a specific issue, such as rights to particular lands. A notary so commissioned might have his own imbreviature for some of the acts in question from which he could draw up “originals,” and if the client had brought older, or simply other, documents redacted by other notaries the commissioned notary could copy these documents into the collection. Such a notary could simply state that he was making a faithful copy of another notary's work. We have an example of this from the LN1 on folio 9r where Guido Iohannis concludes his copy (exemplum) of a document redacted by Ambrosius Aghitione de Gaydaldis on 14 December 1242 by declaring,

I, Guido Iohannis notary, transcribed and signed the above instrument at the command of lord Citadinus, judge and vicar of lord Aldrovandus podestà of Città di Castello, following that old aforesaid [document] written by the notary Ambrosius, neither adding nor subtracting anything from it by which its meaning or substance could be changed or varied in anything, in the year 1242 on the twenty-seventh of December during the reign of the Roman Emperor Frederick, fifteenth indiction.Footnote 29

The notary might also have two to three other notaries authenticate the copy, certifying that it was a faithful and accurate copy by affixing statements to that effect and their signa.Footnote 30 Note that it was only when a notary was copying the instrument of another notary that there is any indication that the document is a copy; if he was drawing on his own imbreviature the document appears as, and technically is, an original.

The booklets of the LN1 incorporate copies throughout to provide evidence of the commune's earliest acquisition or possession of lands and rights.Footnote 31 Arcaleni's insightful study of the chronological distribution of copying in the LN1, in fact, shows that Città di Castello's government was not entering every act it effected in its black book. Not only are the documents not ordered in a chronological series, but there are also many lacunae, stretches of a year or several years without any documents.Footnote 32 The commune was commissioning booklets — some as simple as a bifolio, others true quaterni, still others consisting in multiple gatherings — for particular purposes on specific issues. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the commune most intensively had booklets created during periods of political crisis.Footnote 33

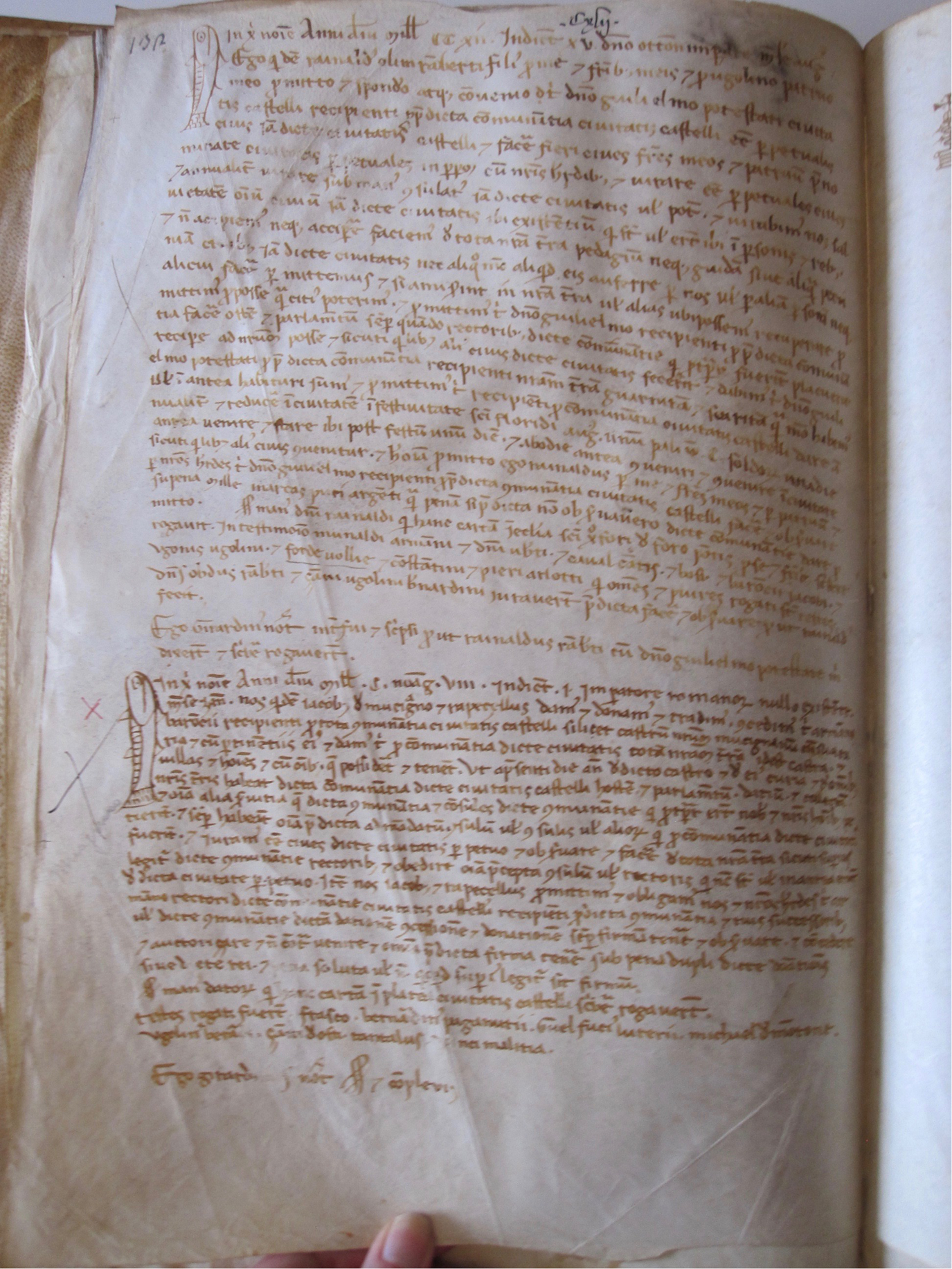

Now that the purpose of the LN1 as a liber iurium is clear, and the methods of its compilation as commissioned booklets on particular issues is evident, we can return to those four earliest “original” documents of January 1198, 10 September 1203, and August 1212. As I noted earlier, these four are concentrated in one section of the LN1, on folios 129v, 130r, and 132v. Three of the four were redacted by one notary: Girardinus, whose signum is a fish that dances next to the opening lines of each of his documents. The earliest “original” document in the LN1, dated January 1198, records the submission of two elites, Iacobus and Rapercellus of Muccignano, to the commune of Città di Castello. They give over their castle at Muccignano, its district or curia, and all their lands, promising to answer the consuls’ summons to serve in the city's military host, to attend the city's parlamentum, and to pay dues and fees. This document is on the same page, folio 132v, as another of Girardinus's dated August 1212 that records a similar submission to the commune of other rural elites: Rainaldus olim Ramberti, in his own name and in that of his brothers and their godfather (padrino) Ugolinus, promises the podestà that they will be citizens of Città di Castello in perpetuity, swearing the required oath of citizenship every year, serving in the host, attending the parlamentum, and exempting their fellow citizens from paying tolls (pedagium) to cross their lands (Figure 1). The clue that these are munda being written out by Girardinus at some time after the acts they record is their arrangement on this parchment page: the August 1212 document is written at the top and after it, fit into the remaining space, is the earlier document of January 1198. The other August 1212 document by Girardinus, written out on folio 130r, records another submission — of Petrus Arlotti, Magone, and Martinellus, on their own behalf and for other Tiberiis — enacted at the same place as the August 1212 document on 132v (in ecclesia sancti Christofori de Foro Pontis) and making the same promises to the podestà of Città di Castello. When might Girardinus have written these “originals”? This notary had a long and very active career from at least November 1196 through 4 November 1242, chiefly recording acts of the cathedral chapter. This gives us a rather ample window, from 1212 to 1242, when Girardinus could have written out these munda from the imbreviature in his own registers.

Figure 1. Città di Castello, Archivio Storico Comunale, Diplomatico, Libro Nero I, fol. 132v, document 1, dated August 1212, at top and below it document 2, dated January 1198, both redacted by the notary Girardinus.

The 10 September 1203 act is the sole document on folio 129v and it faces, on the same piece of folded parchment, Girardinus's August 1212 document on 130r (129–30 is a bifolio). It memorializes the submission of rural residents to the urban commune, but these individuals — described as “the consuls and leading men of the castrum of Monterchi” — constituted a self-governing community akin to the city's.Footnote 34 Like the groups in Girardinus's documents, they swore to be citizens in perpetuity, but here the meaning of this commitment is made more clear: they pledged to guard and protect the men of Città di Castello and their property in good faith and without deceit, collectively and individually. In particular, they swore to hold and maintain the castle of Monterchi ad honorem civitatis castellani and to obey the orders of its consuls and rectors. The document was redacted by the notary Iustinus and this is the only piece of his work in the Libro Nero. He does not appear in either Magherini-Graziani's or Giovanni Muzi's histories of the city, and both of these authors transcribed, in whole or in part, many documents in their annotation and appendices. Although I cannot say with absolute certainty at this stage in my research that he was not redacting for the cathedral chapter or see, he was not one of the notaries frequently working for these institutions in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century. He may have come from Monterchi with the consuls and leading men of the castrum. While it is possible that this document was written on this piece of parchment in 1203, this seems to me less likely since the other document sharing the bifolio could not have been written on the piece before 1212. The placement of these documents in the LN1 and the content of other documents in this section, moreover, suggest that these early “originals” were written out after 23 June 1223.

The folios with these early “originals” follow a quaternus that is the smallest within the LN1 (330 x 235 mm, or 13 x 9 1/4 inches). A distinct gathering (a quaternion missing the seventh leaf), it is made up entirely of documents dated from 1221 to 1223 relating to a political crisis that suddenly reoriented the commune's alliances. Since 1180, Città di Castello had been a subjugated ally of its larger and more powerful neighbor to the south, Perugia: in the treaty of that year, the city's consuls — with the consent of Città di Castello's bishop, clergy, and people — submitted the town to Perugia, promising always to support Perugia in war and peace and agreeing to maintain Perugian ambassadors in the city at their own expense.Footnote 35 After an attempt to break out of this subjection led to a resounding military defeat, the treaty was renewed and confirmed in 1219.Footnote 36 When still smarting from this defeat and recapitulation, fortune smiled on Città di Castello. In 1222, long simmering disputes between the popolo of Perugia — a sworn association of dissident elites — and the city's older ruling elites who styled themselves “knights” (milites) and who had long dominated its commune, came to a head. The popolo rose up, chased the milites out of town, and seized control of the city and its fortifications. A contingent of these Perugian milites sought refuge in Città di Castello, and the Castellani drove a hard bargain in negotiating the conditions of the hospitality they would offer. The Perugian exiles had to renounce control of areas within Città di Castello's territory that they claimed at the end of the 1219 war, effectively confirming the Castellani's possession of the castles of Citerna and Montone, and they had to promise to protect Città di Castello should the Perugian factions come to terms. The Castellani agreed not to respect the terms of their previous treaty with Perugia since the city was now held by the popolo, essentially allying themselves with the humbled exiles.Footnote 37

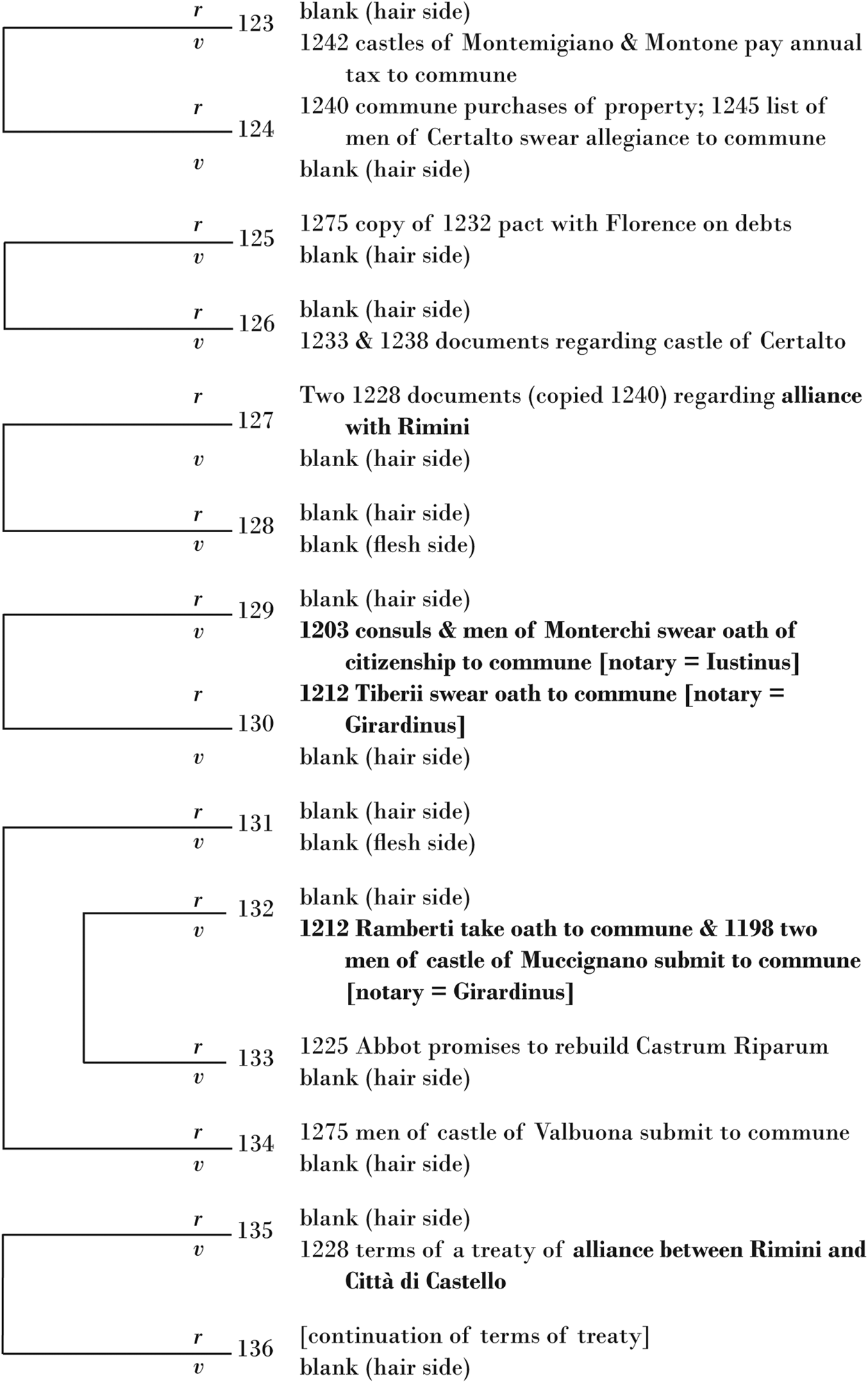

After this gathering in the LN1 regarding the Perugian exile crisis of 1222–23, and before a small “organic” gathering (fols. 137–40) that is entirely the work of one notary (Citadinus), there is a choppy section of individual bifolios from 123r to 136v (see the collation diagram in Figure 2) that treats the post-1223 solidification of the commune's southern border and then expansion to the northeast. The first two bifolios (123–26) document the commune's control of the castles of Montemigiano and Montone on its border with Perugia, and of Certalto on its border with Gubbio, as well as its 1232 pact with Florence to its northwest.Footnote 38 The rest (fols. 127–36) are bookended by two sets of documents related to an alliance between the communes of Città di Castello and Rimini. On folio 127r there are two documents related to the negotiation of this alliance, both redacted in Rimini: in the first one, dated 2 November 1228, Rimini's podestà, at a meeting of the commune's council, nominates two vicars (vicarii) to lead the commune, and in the second, dated 8 November 1228, these vicars nominate Gualterius Calliansi of Rimini as “actor, procurator, and syndic” charged with negotiating a compromise with the commune of Città di Castello relating to an alliance between the two cities. These are both authenticated copies made by the notary Bonagratia Çani on 30 December 1240. On folios 135v to 136r is the long document setting out the terms of the alliance, dated 13 November 1228 and enacted in the communal palace in Città di Castello. This is an original redacted by the notary Cato. All four of our earliest “originals” are in the section bookended by the Rimini treaty documents. The copying in 1240 of the two documents relating to the Riminese negotiator of the treaty suggests that this bookended collection of folios was initially organized in that year, but there was a later addition in 1275. One bifolio (fols. 131 and 134, a single sheet) containing one document dated 1 February 1275 (on 134r) was wrapped around the bifolio 132–33 sometime before the ca. 1350 numeration of the volume.Footnote 39

Figure 2. Collation and contents of Città di Castello, Archivio Storico Comunale, Diplomatico, Libro Nero I, fols. 123r-136v.

Between the two sets of acts relating to the alliance with Rimini are six documents: the four earliest originals, all recording submissions of rural communities and elites to the commune of Città di Castello and two others making related concessions. On 133r is a document of 18 September 1225 redacted in the same church, San Cristoforo de Ponte, where two of Girardinus's submissions took place. Now, in 1225, there is a monastery at the church, and in this document its abbot Ildebrandus promises the commune's treasurer (camerarius), Rainaldus Baldovini, that he will complete the rebuilding of Castrum Riparum, as the council of the commune wishes, and not allow the building of other edifices or towers without the consent of the city's podestà and council (under the penalty of a hundred marks of pure silver). And on 134r is that much later document of 1 February 1275 in which the men of the castle of Valbuona (or Valbona) in Massa Trabaria, gathered in council with their consuls, Piçone Corboli and Iacobus Iohannis, appoint a procurator (Ugo Ugolini de Fossato) to carry out on their behalf the task of submitting their castle, with its fortifications and men, to the dominion, rule, and jurisdiction of the commune of Città di Castello in exchange for the commune's promise of protection.

All these submissions are relevant to the alliance with Rimini, and geography is key to understanding the connections. Although the treaty established a broad military and diplomatic alliance, requiring Città di Castello “to hold the friends of the city of Rimini as friends and its enemies as enemies,” trade and safe conduct through Città di Castello's territory was the primary aim of the agreement. The first clause in the treaty exempts citizens of Rimini from paying tolls (pedagium), taxes on purchases (siliquaticum), or any other exactions and the second affords them safe conduct throughout Città di Castello's territory. All these submissions establish the commune's control of the roads and passes to the northwest (in the direction of Rimini), to the east (in the direction of Arezzo), and to the southeast (in the direction of Castiglion Fiorentino and Lake Trasimene). The castle of Muccignano (fol. 132v January 1198) overlooks the road running southeast through the Valle Nestore and the castle of Monterchi (fol. 129v 10 September 1203) in the northern Valtiberina is on the road to Arezzo. The remaining four acts all relate to families and fortifications on the northwest road along the Metauro river that connects the upper Valtiberina and Città di Castello to Urbino and then Pesaro and Rimini. The “Tiberii” (fol. 130r August 1212) and Rainaldus with his brothers and godfather (fol. 132v August 1212) were elites in the region called the Massa Trabaria, part of which was within the territory of Città di Castello and part in the territory of Urbino. Rainaldus appears to have had lands and interests around San Giustino where the northwest road enters the Valtiberina just north of Città di Castello as well as in the county of Urbino; his heirs were powerful enough to be named in the treaty with Rimini (filiis Rainaldi) as among citizens of Città di Castello beyond its borders who were included in the agreement about coming to the aid of citizens detained.Footnote 40 The “Tiberii” were citizens of Città di Castello living around that Castrum Riparum, or Castel delle Ripe, in Urbania just beyond the territory of Città di Castello in the county of Urbino. This fortified community was the one rebuilt by the monastery of San Cristoforo de Ponte (fol. 133r 18 September 1225) at the behest of the commune of Città di Castello. And, finally, the castle of Valbuona (fol. 134r 1 February 1275) was also along this northwest road between Castel delle Ripe and San Giustino.

In sum, the four earliest “originals” were most likely written out after the 1223 pact with the Perugian milites that settled the commune's southern borders and in the context of the negotiation of the 1228 treaty with Rimini. All of them document the commune's control of the roads allowing Riminese merchants and their goods to travel through Città di Castello's territory and all of them are sandwiched between the Rimini treaty instruments. Indeed, the 1221–23 gathering of documents relating to the Perugian exile crisis appears to be the earliest “booklet” in the LN1 and this accords with Arcaleni's conclusion that “the most considerable part of the documentary production brought together in the Libro Nero I dates from the period 1221–1272.” The earliest I think we can say that the commune of Città di Castello made the leap from single-sheet parchments to the booklets that ultimately became the constituent units of its first register is 1221.

Ecclesiastical Institutions

So much for the commune. When did the city's leading ecclesiastical institutions begin to produce books or booklets? The cathedral chapter, not the bishop, was the earliest innovator. Today the entire capitular archive is in the Archivio Storico Diocesano, which was established in the building of the old diocesan seminary in 1978. When Brentano visited in the 1960s, the “bishop's books” were still in the bishop's palace and the archives of the canons were, as Brentano wrote, “deposited in a room in the old capitular buildings attached to the Duomo.” His appraisal was that they

seem, at least from a superficial search, to be interesting but not in any way spectacular. In the main body of original medieval documents in this collection, individual documents date from as early as 1020 and as late as 1578. There seem to be about two hundred of them, a good, small collection, helpful in a scattered way.Footnote 41

Apparently, whoever gave him access to the collection only showed him the pergamene sciolte, the single-sheet parchments. And, it is true, this section, the Fondo Diplomatico of the capitular archives, is exactly as Brentano described it: a collection of 183 parchments dating from 1020 to 1578. There are, however, it turns out, two other medieval series of documents for the cathedral chapter: rolls and books. The latter, the Libri, are of several types: for the thirteenth century we have libri di istromenti, libri di straordinari, and libri delle entrate (income); in the fourteenth century the types proliferate further.

The opening of the first “Book of Instruments” places us at the origin of the chapter's new system of registers (Figure 3).Footnote 42 The notary Benencasa announces that he is creating this breviarium istrumentorum (an epitome or summary of documents) so that the canonry's documents “are able to be found in a dignified condition, found more easily, and [so that] those almost consumed by age may be restored, lest they be consigned to oblivion.”Footnote 43 He then attests that he is summarizing the old documents, not adding or subtracting anything, and begins with the roll (rotula/rotulus) marked with the letter “A.” The first six pages of the Liber contain his brief summaries of the sixty documents in roll A, the next five pages the summaries of the sixty documents in roll B, and then three more pages with the forty-three documents in roll C.Footnote 44 Note that Benencasa's prologue to his breviarium provides three reasons for abandoning single-sheet parchments in favor of registers. First is a need for the chapter's documents to be found graviter, in an impressive or dignified manner, with propriety or dignity. This suggests that internal administrative efficiency was not the primary motivating factor: someone who might need to see the chapter's documents needed to be impressed by the propriety and dignity of the community's record keeping. Second, the chapter's documents need to be found facilius, more easily. While this does indicate that the community's members or officials needed to be able to find individual documents more swiftly, it also seems to presume that demands to see particular documents were being made or were likely to be made. Finally, Benencasa invokes the oft repeated admonition that old and worn out texts be renewed, reformed, remade (reformantur) in order that their contents not be irretrievably lost. While the commune of Città di Castello left no rationale for the creation of its Libro Nero, this notary working for the cathedral chapter thought some explanation for its documentary innovation was needed. This is a significant fact to which we will return.

Figure 3. Città di Castello, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Archivio Capitolare, no. 132, fol. 1r, the opening of notary Benencasa's breviarium istrumentorum.

The rolls Benencasa summarized at the opening of the cathedral chapter's first register do not survive to allow us to assess for ourselves how uetustate pene consumpta, how ancient, nearly destroyed, they were or how undignified the documents comprising them appeared. But one can readily see from the summaries how difficult it would have been to find any single document in them. The parchments Benencasa was summarizing apparently were sewn together, end to end, in no consistent chronological order. The opening documents on roll A, for example, are dated 1078, 1099, 1078, 1084, 1082, 1140, 1100, 1105, and 1077. The individual parchments were redacted by different notaries and recorded different kinds of acts. Of the 163 documents Benencasa summarized from rolls A, B, and C, slightly over half (eighty-eight, or fifty-four percent) were donations of lands to the chapter, roughly a third (fifty-one, or thirty-one percent) were leases, and the remaining documents (twenty-four, or fifteen percent) recorded a mix of sales, exchanges, renunciations, and dispute settlements. If there was a system of property management in these rolls, it is difficult to discern. The chronologies of the rolls overlap: roll A contained documents from 1030 to 1168, roll B from 1037 to 1183, and C from 1076 to 1186. There is a vague geographical organization, but with myriad exceptions. Many of the lands identified in the parchments of roll A were in the northwestern part of the diocese: at Petriolo, Sansepolcro, and further north and west around the baptismal church of Santo Stefano.Footnote 45 Roll B contains a mix of documents, many about properties in the city of Città di Castello and then lands along the Tiber, some just south of the city at Canoscio and San Savino, most west (Teverina, Cagnono) and then in the same northwest quadrant (Sansepolcro, Santo Stefano) as in roll A.Footnote 46 Many of the properties on roll C are south of the city at Uppiano, San Savino, Canoscio, and Arcelle, but there are also lands north of the city at Castiglione, Selci, Pitigliano, and San Cassiano.Footnote 47

Some evidence suggests that in creating these rolls the canons were juxtaposing donations of lands and then leases relating to them. The opening document on roll A, for example, is a donation in 1078 by Dominicus Orsi of Pariolo and his wife Rocia of all their property (omnes res proprietatis) to Iohannes the provost of the cathedral chapter. The document just following it, dated 5 March 1099, records Iohannes, archpriest of the chapter, leasing to Dominicus and Berta of Petriolo “all the lands which Dominicus and Rocia gave to the canonry,” plus several others, for an annual rent of seven denarii, ten stara of grain, and fifteen of wine, due in August.Footnote 48 Another example on the same roll reverses the order: Benencasa's summary of parchment ten records the provost Iohannes in 1077 leasing to Berta daughter of Ranieri of Illazo, wife of the deceased Lambertus, lands “which the aforesaid Berta gave to the canonry” and then parchment eleven, dated July 1077, records Berta wife of Lambertus donating “all the goods which she had from Lamberto” to the chapter.Footnote 49 Roll C, however, provides an example of documents concerning the same lands not sewn directly together: summary thirteen reveals the prior of the chapter leasing in April of 1096 the property “that belonged to Teuzo of Toicano” and much later in the roll document forty-three records the sale in April of 1085 by Teuzo's son Ingizo of eighty tabulae of land to the canons.Footnote 50

Page fifteen marks a transition in the Liber: it opens with two original documents from 1191 redacted by Benencasa on the same day, both renunciations of lands held from the chapter on which back rent was owed. Below them Benencasa copied, from another roll (extera rotolum), an 1158 sale of land in Ortola by two brothers, Castelanus and Iohannes, sons of Ugobardus de Rufiano, to Guiducio Corbo and an 1133 lease of lands near the church in Piosina on the Tiber by Prior Gerardus to Ranucio Iohannis de Girardo. Finally, there is a copy of a lease of lands in Meltina dated April 1148 copied by a different notary, Rainerius, with two other notaries also signing off on the authenticated copy. There is no apparent relation between these five documents. The verso of this folio, page sixteen, is blank and then a new gathering begins on page seventeen. From this point in the codex on, the documents are original entries and are in a rough, although not entirely consistent, chronological ordering from the first dated 1193 through the last dated 1216. Benencasa does not give us the date when he made his summaries of the canonry's old and deteriorating documents kept in parchment rolls. In that the earliest documents in the subsequent gatherings are 1192–93 and the latest documents in this opening quaternus summarized by Benencasa are from 1191, however, it seems reasonable to date the innovation of the new register system, at the latest, to 1192.

Were the gatherings or booklets that now comprise this first volume in the chapter's series of books actually bound together in the Middle Ages? While the volume's current binding is modern there are two medieval numberings of the gatherings present. The medieval numbering in roman numerals on twenty-six of the twenty-eight quires, located on the first folio of each gathering in the upper right corner, accords with the arrangement of the quires surviving today. Gatherings two to twenty-seven are sequentially numbered ii to xxviiij with original quaterni viij and ix missing. The final gathering is not numbered and the opening quaternus is numbered one (j) on its final folio (page sixteen in the modern pagination), but “viiij quat(ernus)” on the opening folio in the upper right corner. The labeling of what is presently the first gathering — with Benencasa's prologue and summaries of rolls A, B, and C — as the ninth quaternus indicates that the arrangement of the gatherings we see today was preceding by another organization, probably including more pre-1192 documentation from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.Footnote 51 But the consistent sequence of medieval numbers of the gatherings indicates that they were arranged as we have them today in the Middle Ages, likely (from the script) before the mid-thirteenth century.

The new system recorded the same kinds of acts regarding real property as did the old, but in a different form. Most of the documents summarized by Benencasa were donations and leases, and those added thereafter were predominantly leases, particularly the long-term livello (or libellus) leases enduring three generations that ecclesiastical institutions tended to favor. Instead of these acts being recorded on separate parchments and then stitched together end to end and rolled, the new book form did give these documents a more dignified appearance. The size of the pages — measuring 368 x 254 mm (or 14 1/2 x 10 inches) — and the rendering of the text in two columns treated these collected land management records like liturgical or literary texts.Footnote 52 Bound like such texts too, the chapter's new registers definitely achieved the first rationale offered by Benencasa: the documents of the cathedral canons could be found graviter, in an impressive or dignified manner. The general chronological ordering of the documents seems likely also to have made the canons’ instruments easier to find. This change in form, moreover, was enduring. Nine of these books of instruments survive down to 1407, but the gaps in chronological coverage suggest there were more. Most are the work predominantly of one or two notaries: the first book, covering down to 1216, was the work of Benencasa and Mercator; the next surviving one, covering 1233 to 1248, was just about entirely Girardinus.

Most valuable in the archive of the cathedral chapter is its preservation of all three forms of record-keeping in its medieval documentation. Rolls A, B, and C seem to have been discarded once Benencasa summarized their contents, but two twelfth-century rolls and three thirteenth-century rolls survive. The twelfth-century rolls are both entirely the work of one notary, Wilielmus, one containing a series of leases from 1161–63, the other a more miscellaneous collection of documents (leases, gifts to the chapter, and a refutation) all from 1163. There is no overlap between the documents here and the summarized instruments Benencasa recorded (which is probably why they were preserved), but they are similar in character to the contents of the summarized rolls. The rolls of the thirteenth century, however, have a different character, suggesting a conscious change in record-keeping. Instead of recording documents relating to the regular, ongoing administration of the chapter's lands, each of these three rolls was drawn up in relation to a conflict. One dated 1204 contains a series of documents recording agreements between the bishop and chapter of Città di Castello, on one side, and various parties in Borgo San Sepolcro, on the other, regarding discordia arising from the “translation” of the area's baptismal church from Bocognano into Borgo San Sepolcro.Footnote 53 Roll four dated 1238 is a series of witness testimonies concerning lands and rents in Centoia while roll five contains documents and witness testimony concerning an acrid 1292 dispute over the cadaver of Benvenuta, a sister of the Order of Penitence, which both the Franciscans and the cathedral canons claimed the right to bury.Footnote 54 In sum, rolls seem to have continued to be used for documentation relating to litigation while the new registers or “books” were for the day to day administration of the chapter's landed patrimony. Why might the chapter have continued to use the roll form for litigation? Probably because rolls were more portable and, in fact, the documents comprising them were redacted in different locations related to the disputes they documented.

The chapter continued to preserve single-sheet documents but the number and character of these parchments change. Generally, the eleventh- and twelfth-century documents are mainly donations and privileges with a few leases, whereas the substantial collection of thirteenth-century parchments contains thirty-seven leases, only five donations, and the rest a mix of documents relating to legal cases, clerical appointments, sales, and wills. And then the number of single-sheet parchments drops off sharply in the fourteenth century, most documents related to legal cases or leases.Footnote 55 The thirteenth century was clearly one of transition where the status of the centuries-old custom of drawing up documents on single pieces of parchment lost ground to the new model of entering them in booklets and books.

Fifteen years after the chapter created its first register, the bishops of Città di Castello began their “books.” The oldest gatherings in the great nine-volume collection of episcopal acts surviving today in the Archivio Storico Diocesano are in volume two, folios 82–136. The section consists of a folio (82) connected to a stub in a previous gathering and then eight other quires, all comprised of smaller format parchment leaves of 320–40 x 220–30 mm (roughly 12 1/2–13 x 8 1/2–9 inches) in comparison to the 430 x 320 mm (17 x 12 1/2 inch) pages of the rest of the volume (Figure 4). It is the product of a concerted program of copying older documents and redacting new ones begun in 1207–8 by the notary Martinus. A total of forty-five earlier documents, with dates ranging from 1089 to 1198, were copied with the great majority (thirty-five) of these copies carefully dated, another four undated but with a notarial indication of the copying,Footnote 56 and only six ambiguous. Five of these are in Martinus's hand and one in that of the notary Albertus who had authenticated Martinus's copy of an 1164 document on the same page.Footnote 57 The copies of earlier documents are spread over six of the gatherings with 94r–103v entirely comprised of copies.Footnote 58 The two quires comprising folios 110r–23v contain all new redactions dating from 1207–11. This series of booklets continues in the first eight quires of CCASD, AVC, Reg. 1: 1v–58v.Footnote 59

Figure 4. Città di Castello, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Archivio Vescovile Cancelleria, Reg. 2, opened to fols. 81v-82r, with the smaller format booklet (comprised of fols. 82-132) that is the earliest in the entire series of episcopal registers at right.

Why Change?

Martinus's copying in 1207–8 coincided with the beginning of the episcopate of Iohannes II (1207–26) who came out of the cathedral chapter. Until 1204 Iohannes was camerarius of the chapter, so obviously intimately familiar with the administration of its patrimony, and late in 1204 he became the chapter's prior. In 1205 the episcopal see was vacant, but it was Iohannes who vice episcopi laid the first stone of a new monastery at the behest of its abbot, and by 5 February 1207 Bishop Iohannes was the recipient of a privilege of Innocent III confirming the see's patrimony.Footnote 60 There would seem, therefore, to have been a direct transfer of administrative methods from the chapter to the see through the person of Iohannes.Footnote 61

The reasons for the change in documentary practices are explained in a document that gives an account of a supplication to the pope that Iohannes made in person during a provincial synod at Viterbo that Innocent III presided over on 21–23 September 1207. Indeed, the document is in the small gathering (fols. 104r–9v) which begins the section of original new documents after the quire (fols. 94r–103v) that is entirely copies of twelfth-century documents made in 1207–8. Tearfully imploring the pope to relieve the great misfortune of his see, Bishop Iohannes lamented its temporal and spiritual poverty, the fault of past bishops, but also of clerics and laymen who deprived it of tithes and bequests and alienated its lands. Bishop Iohannes's remedy for the dire state of the see, for which he begged Innocent's aid, presumably financial, was the scribal project we see in the notary Martinus's quaterni. Iohannes got right to the point in his brief peroration before the pontiff. It opened, “By those agreements among men strengthened by the witness of written instruments … we are taught to cease immediately from past evils, to beware present ones, and to drive away future ills. For that reason, we are striving so that the state and property of the see of Castello be restored in scriptis,” in its writings, its documents, “so that in the future its bishops may avoid their predecessor's inertia and sloth, with the attendant losses [of property], and avoid evil and abominable contracts lest they commit under the pretense of piety an impious crime by alienating the goods of the see.”Footnote 62

The bishop's plea calls our attention to the cost of implementing new documentary systems as well as the costs of failing to maintain the kinds of written records apparently increasingly necessary in the changing cultural, political, and legal climate of late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century Italy. While the chapter appears to have had the resources to implement its new administrative system of registers in 1192, it seems that some infusion of papal support was pivotal in the origins of the see's registers in 1207–8. This papal funding was likely not the result of Innocent III's compassion for the new bishop alone: the diocese was directly dependent upon the Holy See and it bordered the pro-Imperial Tuscan see of Arezzo making it a frontier of the papal state.Footnote 63 Aiding the see of Città di Castello was an investment in retaining lordship over it.

While Bishop Iohannes clearly indicated that he saw the reform of the see's documentary practices as necessary to address its fiscal crisis, the impetus behind the chapter's initial innovation of registers is only hinted at in the notary Benencasa's preface to his breviarium of rolls. Benencasa did invoke the need for the chapter's documents to be found graviter, in an impressive or dignified manner. This raises the question: who were the canons preparing to impress? The date of the chapter's initiation of its first register, no later than 1192, suggests it was likely Henry VI. The canons had received imperial protection from his father, Frederick I Barbarossa, in a diploma of 1163.Footnote 64 Frederick died on 6 October 1190 while on crusade and with Henry VI's accession to the throne the canons rightly surmised that the new king would soon come to Italy to be crowned emperor. He crossed the Alps, entered Lombardy in January 1191, and was crowned in Rome on 15 April.Footnote 65 Emperor Henry VI proceeded south to vindicate his wife Constance's claim to the crown of the Norman Kingdom, but his brother Philip, now duke of Tuscany, did issue a diploma to the canons of Città di Castello in 1196. It not only took the chapter under his protection but ordered that it be held immune from all illicit exactions and that any properties unjustly alienated be restored. The duke, moreover, explicitly declared it illicit for the city's consuls, rectors, or citizens to disturb the canons with exactions, to detain or invade its lands or goods.Footnote 66 Sadly for the episcopal see, the emperor in the same year established relations with the city's commune. Although he demanded a substantial annual payment of thirty marks of pure silver, he took the city, its citizens, and goods under his protection and granted judicial authority within the city to the consuls.Footnote 67 This opened the way for the (unprotected) episcopal patrimony to begin to be absorbed by the urban commune, thus contributing to the financially desperate situation Iohannes II found when he finally acceded to becoming the city's bishop in 1207.

The commune's position of strength relative to the bishop probably delayed its own documentary revolution until the early 1220s. The spur to change seems to have been the political crisis brought on by the arrival in Città di Castello of that band of knights (milites) forced out of Perugia by the popolo's seizure of power in that city in 1222.Footnote 68 The earliest booklet in the Libro Nero, and the smallest, is the 1221–23 quaternus containing a series of oaths and agreements in which the commune sides with these exiled elites, renouncing the city's longstanding alliance with and submission to Perugia of 1180, confirmed as recently as 1219–20. This began a period of escalating hostilities between the commune of Città di Castello and the city's bishop as the commune even more aggressively laid claim to episcopal castles and rights.Footnote 69

Clearly, the “early adopters” of new information systems in this thirteenth-century Italian city were ecclesiastical institutions, not the lay commune, and the early dates of innovation in Città di Castello help clarify causation. As noted at the outset, there has been some resistance to crediting ecclesiastical leaders with innovating registers. If not attributed directly to the influence of the commune, changes in episcopal administration and documentary practices are explained by either a general increase in recourse to notaries or the tendency of notaries to work both for the commune and ecclesiastical clients.Footnote 70 Notarial promiscuity, so to speak, is definitely evident in Città di Castello: the notary Girardinus, to take just one example, redacted documents for the chapter, the bishop, and the commune.Footnote 71 While notaries were definitely key partners in creating these new systems, no notary innovated on his own without an explicit request or order to do so from the elite leaders of these institutions who exercised seigneurial and spiritual powers in the city and countryside and were responsible for their institution's patrimonies. The financial outlay to begin these registers was considerable, involving not only the labor of copying older documents but also the book size (if not quality) of parchment sheets used (rather than the narrow leg-pieces usually reserved for leases, etc.). Even the limited information we have about the social composition of the commune of Città di Castello suggests that notaries were its servants, not leaders: none of the individuals listed as consuls identified themselves as notaries and many were called “lords,” leading Magherini-Graziani to conclude a “prevalenza dei nobili nel governo del Comune.”Footnote 72

When ecclesiastical leaders are acknowledged, the tendency has been to credit the papacy, particularly the reform efforts of Innocent III (1198–1216) and, more specifically, the Fourth Lateran Council (1215).Footnote 73 Attilio Bartoli Langeli explicitly linked the phenomenon of episcopal registers to Pope Innocent III in his review of Federica Barni's study of Bishop Iohannes II of Città di Castello and Giuseppe Gardoni saw the roots of Mantua's episcopal registers in papal pressure and the Fourth Lateran Council's canon eight. Obviously, the fact that Città di Castello's cathedral chapter was compiling its first register no later than 1192 undercuts crediting Pope Innocent III with advising the compilation of registers and none of the Fourth Lateran Council's canons sets out anything like this requirement.Footnote 74 The origins of the bishop's books in 1207–8 also eliminates this great ecumenical council and its legislation as a cause.Footnote 75

It was local ecclesiastical leaders in Città di Castello who initiated its documentary revolution. They did so not to conform with papal or conciliar mandates but to protect the economic resources upon which their spiritual mission and enterprises depended. Those resources were threatened not only by the political uncertainty and strife that characterized the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries throughout Italy, but by the rising power of communal governments and their tendency to try to tax or absorb ecclesiastical properties. While none of the individuals threatening the lands of Città di Castello's cathedral chapter are named, the 1196 diploma of Duke Philip of Tuscany that the canons’ new registers likely helped gain does explicitly offer protection from the consuls, rectors, and citizens of the city — that is, its communal government. Those seizing episcopal properties during Iohannes II's episcopate, and those of his successors over the rest of the thirteenth century, were definitely leaders and supporters of the commune.Footnote 76 In sum, the chronology of documentary innovation in this one Umbrian town shows that ecclesiastical institutions deserve credit in the making of the “documentary revolution.” They may have been acting defensively, but their response was creative and highly influential.