In June 2022, after a two-and-a-half-year COVID-19 hiatus, I joyfully returned to Europe for a research trip. My purpose was to develop further my next monograph on queering animal symbols, specifically investigating the history of the Dalecarlian (Dala) horse [Dalahäst]. Dala horses are brightly painted wooden toys that were carved and decorated by farmers through the long Swedish winters as early as the seventeenth century. Thereafter, Dala horses became a national icon and symbol of Sweden at the 1939 World's Fair in New York City. Scheduling also allowed me to attend Midsommar (Midsummer) celebrations in Dalarna (Dalecarlia) County,Footnote 1 Sweden (Fig. 1). This is the region not only where Dala horses first appeared, but also where many of the traditions surrounding the folkloric, highly theatrical, and now de facto Swedish national holiday of Midsommar most likely originated.

Figure 1. A Midsommar celebration around an immense pole on Lake Siljan in Tällberg, Dalarna County, Sweden. Photo: author.

Attending festive Midsommar events for three days in the picturesque region where the solstice sun barely sets, I was struck by the powerful symbolic divergence of the highly theatrical celebrations.Footnote 2 Symbolic divergence occurs when individuals or groups with different interests, values, or perspectives code and assign different or even contradictory semiotic meanings to, and ascribe power to, the same polysemic event or object, reading the same cultural event/object as text to serve their own ideological views. At Midsommar in Leksand, Sweden, attendees could read the dazzling pageantry as a communal and inclusive celebration of Swedish progressive politics grounded in the Scandinavian socialist welfare state; or, to the contrary, attendees could see the public event as harboring an exclusive, right-wing, nationalist ritual that grounds the beliefs of the neofascist Sweden Democrats Party (first founded in 1988 by a group of Nazi sympathizers) in folk tradition employed as propaganda.Footnote 3 Alternatively, some may even see Midsommar as an ambivalent merging of both.

My understanding of symbolic divergence borrows from Vicki Ann Cremona's theory of “cultural transformation vs. cultural continuity.”Footnote 4 I suggest that Cremona's binary construct allows for a mode of active ambivalence—making space for transformation and/or continuity of the same object of study (in this case, contemporary Midsommar celebration in Sweden and particularly Leksand). This ambivalent approach allows for the movement of the symbolic from the denotative (Midsommar represents Swedish culture) to connotative (Midsommar represents particular and/or politicized notions of Swedish national identity as a microcosm of its culture), and moves the manipulated object of study (whether Midsommar's lore, its performance, or its aesthetics) toward public dissemination, reception, and interpretation.

Cultural transformation is a practice where rituals and traditions are assigned original meaning to reframe preexisting cultural performances toward new purposes in contemporary contexts rather than discarding or replacing them. Cultural continuity, on the other hand, maintains cultural practice, not only through annual, prescribed traditions and rituals, but also through the continued propagation of histories that may be factually uncorroborated yet speak to the desired communal identity of the group (in this case, the Swedish people). I argue that both cultural transformation and cultural continuity can be engaged toward political ends, whether paving the way for inclusion, diversity, or representation into established, precedented practices, or attempting to reclaim or even weaponize historic traditions through the lens of an embodied nativist authority, promoting marginalization and intolerance, as thrust forward by the long-reaching arm of late nineteenth-century nationalism. Although historian Joe Perry has demonstrated how radical regimes have historically manipulated festive celebrations toward revolutionary ends (French Jacobins, Russian Bolsheviks, and Germanic Nazis), this study focuses on Swedish Midsommar, a holiday with murky origins whose traditions have mostly been reformed over the past 150 years, but that largely remains politically neutral (at least on its surface), fit for weaving divergent symbolism into its fabric by those with a particular political agenda.Footnote 5

Following a thick description of my experience attending Midsommar in Leksand, where I observed such symbolic divergence in practice, I present a brief critical exploration of the highly educated, socially mobile intellectuals that transformed Midsommar from a localized, regionally specific celebration to a national one, including artists Anders Zorn and Carl and Karin Larsson, curator-historian Artur Hazelius, and author-playwright August Strindberg. Next, I consider the practice of invented heritage that continues to cloud contemporary celebrations of Midsommar and its winter counterpart, Luciadagen [Saint Lucy's Day], with apocryphal pagan origins. Thereafter, I focus on how Cremona's interlaced cultural phenomena can be read through the performative wearing of traditional folk costumes [referred to locally as folkdräkt or sockendräkt], which are central to Midsommar celebrations in Dalarna County and beyond. Finally, I posit that Midsommar celebrations can be read as a divergent symbol that can be claimed and manipulated for opposing political ends.

Symbolic Divergence and Pluralism in Sweden

Before describing my personal experience as an attendee of Midsommar in Leksand, it is essential to unpack briefly the distinct role of symbolic divergence as it informs the uniqueness of Swedish politics and cultural practice. Cremona's model of cultural transformation versus cultural continuity provides scaffolding for a better understanding of the complexities surrounding contemporary Sweden's celebration of Midsommar, but the holiday's role as a performed national symbol is more nuanced and specific. Sociologist Barbro Klein and architect Mats Widbom suggest that all Swedish cultural traditions are based as much on a spirit of “change” as on preservation, though not necessarily employing change as a harbinger of social progress.Footnote 6 Relying on Sigurd Erixon's notion of “cultural fixation” (cultures that remain “fixed” in an unfixed state that deviates between longevity and change), Klein and Widbom further argue that Sweden's historic geographic remoteness and history of an often insular peasant culture led to a necessity for constant adaptation. This approach gave birth to a curated if not invented kind of heritage that ignored the limitations of class boundaries to forge an ongoing national aesthetic “mixture” that was codified and disseminated by intellectuals and artists in the early twentieth century.Footnote 7 The recipe for creating this “mixture” was imagined to yield a new aesthetic that could be easily identified on the world stage as distinctly Swedish, with the intention of branding the nation as both forward-thinking and equally proud of its ancient roots, its agrarian past, and its rapidly industrializing future.

The concept of intentionality remains central to Sweden's understanding of its cultural pluralism as it relates directly to national performances of Swedishness. In a special issue of the Scandinavian Journal of History dedicated to “Images of Sweden,” historians Jenny Andersson and Mary Hilson suggest that Sweden's contemporary identity was forged in the twentieth century when it was deemed a model utopian society in political discourse—“the most modern country in the world.”Footnote 8 While this adulatory label may reference Sweden's established history for progressive social politics and a secular, denationalizing commitment to legislating for widespread civil rights, this interpretation is based on an intentionally limited definition of “modernity” as it connects to national identity. Sociologist Andreas Johansson Heinö argues that although the “values of anti-nationalism and individualism have been successfully incorporated into Swedish national discourse, it does not necessarily reflect a denationalisation or individualisation of Swedish identity” and subsequently its formulation through public events and official nationalized celebrations.Footnote 9 Heinö's clear demarcation between Sweden's denationalization of politics and national identity is couched in Benedict Anderson's foundational theory of “imagined communities” as both a direct influence and product of nation making.Footnote 10 Anderson suggests that communities are distinguished “by the style in which they are imagined.”Footnote 11 Invoking Ernest Gellner's idea that nations are always an “‘invention’” rather than an “‘awakening . . . to self-consciousness,’” Anderson further posits that nation-states should always be considered as multivalent and driven by agenda(s).Footnote 12 Sweden, like all nations, is complex, but with its own particularities of unique cultural identity and nation-making desires.

In contrast to an imagined denationalized Sweden that endorses individualism as a protected civil right, Andersson and Hilson remind us that, for some in contemporary Sweden, visions of a modern, model utopia are driven by conservative and even oppressive actions taken as a response to and propagandizing of “perceptions of threats to the nation state.”Footnote 13 This hidebound purview has set in motion attempts to imagine a collective national ideology through exclusions and intolerance (including racism, sexism, gender inequality, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigration, and ableism) set by a false nativist authority rather than the more stereotypical understanding of a Sweden (and its national symbols) as grounded in inclusive solidarity.Footnote 14 This alternative understanding of pluralism in contemporary Sweden connects to political intentionality as it takes shape in ubiquitous, historically rooted national performances of Midsommar. Furthermore, this approach to a national pluralism corroborates symbolic divergence as a critical lens with which to expand our understanding of performative traditions and rituals, like Midsommar, that have been codified as part of the cultural fabric of Swedish identity while also remaining subject to interpretation, adaptation, change, or manipulation.

Glad Midsommar: 24 June 2022

Upon planning my research trip to Sweden in June 2022, I decided to visit Dalarna County for Midsommar celebrations, in part because it is widely publicized that many of the iconic traditions of the holiday (the raising of the Midsommar pole, dancing, feasting, and the donning of distinct folk costumes or folkdräkt) originated there.Footnote 15 Admittedly, in my initial stages of planning this trip, I had not yet realized that in participating and thereafter researching these performative traditions, the theory of symbolic divergence would clearly take shape in the pageantry presented as a kind of invented, malleable history/historicizing of Sweden's national past, simultaneously ancient and contemporary. In relating my own experience herein, I attempt to uncover how Dalarna, sometimes referred to as Sweden's patriotic “heartland”Footnote 16 and the “province with old and living traditions,”Footnote 17 became so central to Midsommar practices that have been taken up across Sweden. In offering an admittedly affective account of the festivities at Leksand, I corroborate how my own participatory observation gives light to an event that can be claimed as a public embodiment of either cultural transformation or cultural continuity.

Although Dalarna's human history can be traced to the Mesolithic period—originating because of the immense richness of Lake Siljan's life-supporting waters—it was in the sixteenth century that mines rich with copper and acres of fertile farmland supported the rise of cities and towns around the lake's shore, solidifying a rich working class with distinct rituals, folk customs, festive traditions, public pageantry, and unique regional aesthetics that continue to be reflected in Midsommar celebrations today. The Nordic Museum (Nordiska Museet) in Stockholm suggests that the first Midsommar celebrations took place in Dalarna as a palimpsest of the feast day of Saint John the Baptist on 24 June, potentially layered over more ancient, pagan solstice celebrations.Footnote 18 Midsommar was not solidified as a celebration of Swedish identity, however, until the rise of nationalism that swept Europe at the end of the nineteenth century.

Today, the cities, towns, and villages in the bucolic, wooded countryside surrounding Lake Siljan are a destination for primarily Swedish tourists who want to escape to the country for more “traditional” Midsommar celebrations. In the towns of Mora, Orsa, Boda, Rättvik, and Tällberg, each community has its own distinct take on the civic holiday that takes place on the Friday that falls between 19 and 25 June each year. Largely the same rituals and schedules are followed on Midsommar's Eve throughout Dalarna (and to some degree most of the country): after a languorous, boozy lunch of pickled herring, gravlax, new potatoes, strawberry cake, and aquavit (always consumed with choreographed drinking songs), wildflower crowns are plaited and donned, and the pole is decorated, ritually processed, and raised before dancing commences (Fig. 2). All this pageantry is led by local Swedes wearing the colorful, handmade folk costumes unique to each parish.Footnote 19 It is in Leksand, at the southeastern tip of Lake Siljan, that the largest Midsommar gathering in the world takes place, swelling the population from less than six thousand to more than twenty thousand revelers. This is the celebration I attended.

Figure 2. The Midsommar pole in Leksand as it is raised during the celebration, June 2022. Photo: author.

While it is impossible to trace the exact origins of the rituals that unfold on Midsommar's Eve at Leksand each June, it is quite easy to (mis)read them as a romantic, historical pageant reaching into the pre-Christian (if unsubstantiated) past. Around 5 p.m., with the sun shining brightly in the sky, a crowd begins to grow at Sammilsdal, a natural bowl in the land that serves as an amphitheatre, and the center of the celebration. One can almost imagine this as a site for a torchlit Viking assembly [or ting], though historical and archeological records don't exist to prove this.

Within an hour, the area is packed with people on colorful blankets, many wearing variations of Swedish folk dress in richly saturated reds, blues, and yellows, and even more attendees sporting wild, homemade crowns of flowers sourced from the lush meadows and forests of the region. (Farmers allow the public to roam their meadows freely to collect the floral materials necessary to construct the lush headwear.) Likewise, the entrances to the park are decorated with natural arches made of the silvery birches that carpet the countryside. The feeling is festive and fun, with a carnival atmosphere lent by food trucks parked at the upper rim of Sammilsdal. While people are generally joyous and well behaved, a few rowdy Swedish teenagers have clearly imbibed in an afternoon of too much drinking in the hot sun.

At the center of Gropen (“the pit,” the colloquial nickname for Sammilsdal), lies the naked Midsommar pole [midsommarstång or majstång] in wait. Tall, white, and slender, the pole looks like the mast of a great sailing ship sunken in the depths, coral bleached of pigment. Leksand's pole is the largest in the world, standing at eighty-two feet and weighing an immense 880 pounds.Footnote 20 At around 7 p.m. the ritual begins as a young woman sporting the Leksand parish costume (with a damask bodice and embroidered shawl, a handwoven festival apron over striped wool skirts, and a white, beribboned floral cap), performs a kulning, a traditional Scandinavian herding call which uses head tones to communicate across great distances. At Leksand, the kulning is a hauntingly dramatic start to the Midsommar proceedings, while also inviting the procession to begin: simultaneously stretching into the twilight of the Nordic past and projecting into the highly anticipated celebration that is about to unfold.

Meanwhile, on the shores of Lake Siljan, a flotilla of eighteenth-century-style church boats (once used to row their ancestors to Sunday services) appear, filled with dozens of men and women in folk costume, either carrying immense wreaths and garlands of flowers and bright green foliage or playing traditional folk songs on the fiddle. Around the time of kulning performance, the boats begin to land, and the performers climb ashore and begin processing down the main street of the town, where another, smaller Midsommar pole stands decorated. The procession is led by dozens of fiddlers (spelmän), playing the joyful folk song “Gärdebylåten” [The Gärdeby song] in unison. The mesmeric tune, which was composed more than a century ago in the region, has become the ubiquitous opening anthem of Midsommar throughout the entirety of Sweden and in Swedish settlements outside of the country.Footnote 21 Following the fiddlers are dozens more Leksanders, sprightly carrying the natural decorations (called maja) for the Midsommar pole, never revealing how heavy and cumbersome they must be, particularly in layers upon layers of embroidered wool and homespun on an unseasonably hot summer day.

As the procession snakes down the picturesque streets of Leksand, lined with historic buildings painted Falu red, ocher, and white, the excitement builds at Sammilsdal, where a variety of foreign guests are welcoming attendees in various languages (French, German, English, Japanese, Arabic, and Ukrainian, among others). While the crowd is primarily white, looking around I spot several women in hijabs (some adorned with flower crowns) and a group of bubbly, preadolescent Black girls sporting Sweden's blue, yellow, and white new national costume, with bare legs and flashy sneakers. Furthermore, the most widely watched recording of this 2022 celebration on YouTube comes from SwedishPaki Mom, a Pakistani immigrant and content creator whose channel is dedicated to recording Pakistani–Swedish cultural fusions, from celebrations to cuisine.Footnote 22 Although Dalarna has a reputation for political conservatism because of its voting record, the participation of these diverse attendees suggests that Leksand's Midsommar creates a sense of cultural transformation. This mode of openness reimagines regional traditions into a gathering of inclusion, elevating citizenship (whether through birth or naturalization) as a form of national identity rather than defining nationalism as an exclusive and entitled legacy of white, Nordic, nativist genealogy and an authenticating factor of Swedishness. Though Midsommar is certainly Sweden at its most Swedish, this gathering feels more like a celebration of casual kinship than the national patriotism that so often inundates public celebrations of the Fourth of July in the United States.

Soon enough, the rippling echo of the fiddles is heard just outside of the arena, and a wave of excitement passes through the crowd. As the procession enters “the pit,” the acoustics of the bowl magnify the folk music so that it seems to surround you. It is beautiful to the point of being almost overwhelming.

Following a series of folk ring dances to variations on “Gärdebylåten” (the fiddlers are tireless!), the most important moment of the evening arrives: the decoration and raising of the Midsommar pole. After hanging the garlands and wreaths carried from the lake, a group of a dozen or so men in Leksand folk costume (easily recognizable by their beautifully embroidered navy coats [blåtröjan] and broad-brimmed wool hats decorated with pom-poms) begin the ritual. For over an hour, using a set of long, scissors-shaped, forked sticks and brute strength, the pole inches up little by little, with the participants taking much-needed breaks throughout the process. An emcee oversees the process and engages the crowd, announcing each subsequent raising of the pole with an extended call of “Ohhhhhhhhhhh,” to which the crowd responds with a unanimous “Hej!” as the cumbersome, flowery mast is thrust upward and stabilized into each new position on its ascent. As you can probably imagine, when the pole finally reaches its vertical position and is locked into place, almost an hour later, the crowd erupts in a cheer that is certainly heard in the surrounding villages as it echoes across the lake. Summer has returned to once wintery Dalarna, and thousands of people rise and head to the base of the pole to dance, joyfully, as one.

While the Leksand celebration feels deeply tied to the past, it seems (particularly to a visiting American with a penchant for folk heritage, and a childhood spent engaging in some diasporic Swedish traditions in Northern Maine) more performative than it is historical. Although my experience of this Midsommar event, which was purely observational/participatory rather than ethnographic, felt inclusive, diverse, and in line with Sweden's progressive politics, there is a divergent symbolism that renders the national pageant and its components more conservative, and with darker, alt-right inclinations. Prior to unpacking the cultural transformation/continuity inherent in Leksand's Midsommar further, it is necessary to place this event in context by briefly visiting its admittedly murky cultural history as it connects to Swedish identity, to style, and to the rise of populist nationalism.

Midsommar and Romantic Nationalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Sweden

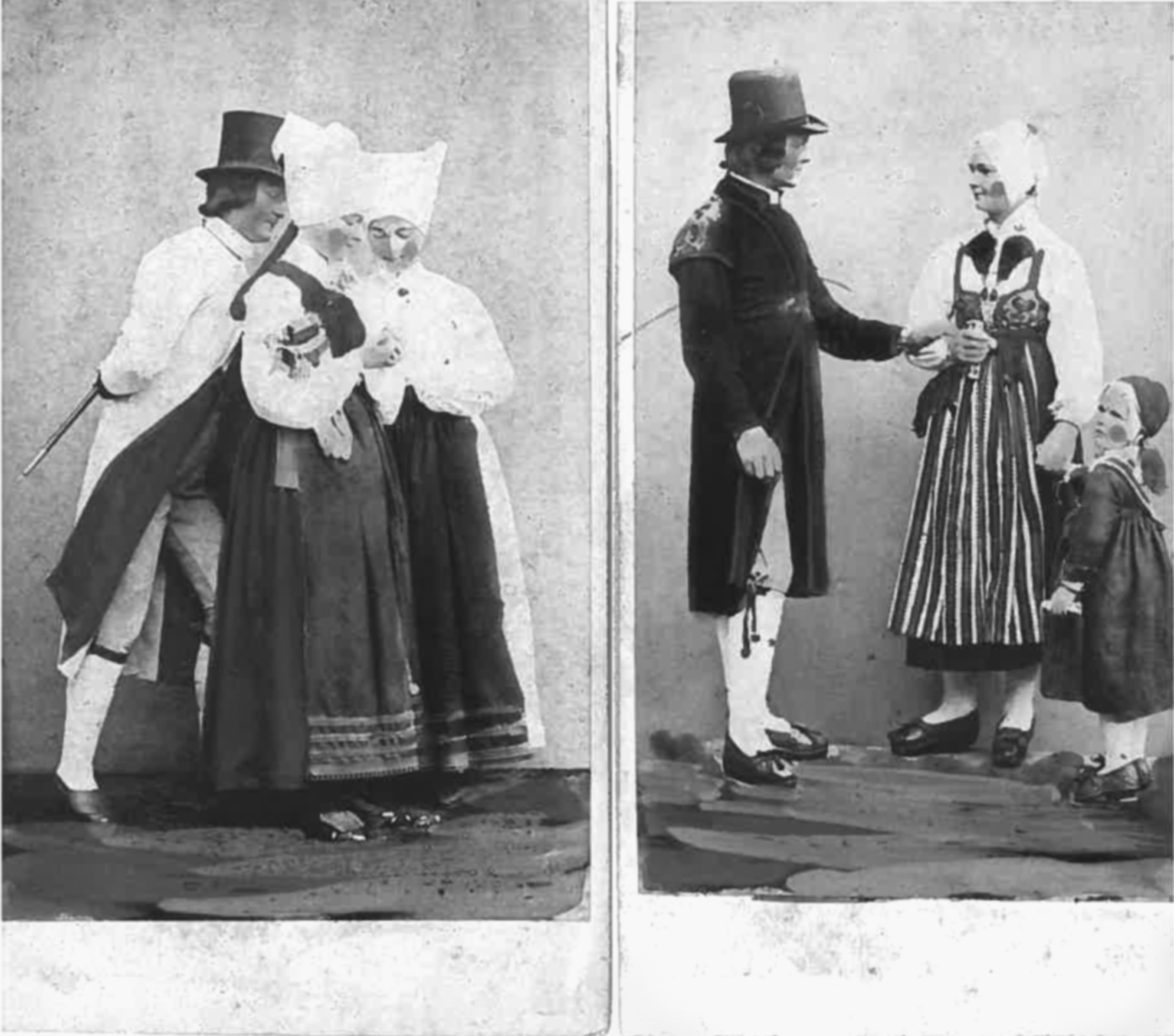

In his work linking folklore to nationalism, David Hopkin argues that in nineteenth-century Europe, folklore was typically “generalised” or “particular” rather than “national, or even regional.”Footnote 23 It was only through the artistic interpretation of the intelligentsia, often in the form of urban artists and writers (Fig. 3), that Dalarna's folkloric aesthetics and celebrations, like Midsommar, became codified, disseminated, and politicized toward national identity as something that could be seen, copied, and engaged. This movement from an aesthetic reframing of folk traditions into an invented continuous, even if flattened and homogenized, Swedish cultural history is rooted in the period when tourist artists began to descend on picturesque Dalarna in the mid-nineteenth century.

Figure 3. A nineteenth-century aquatint engraving featuring a Romanticized view by Elis Chiewitz of a Midsommar pole, cut from an 1827 edition of Carl Michael Bellman's Fredmans Epistlar. Photo: author's collection.

For example, in 1850 Danish painter Wilhelm Marstrand journeyed to Dalarna for a honeymoon with his new wife, Margrethe Christine Weidemann. Coming from the more cosmopolitan, continental city of Copenhagen, Marstrand was enamored to observe locals being rowed across to Leksand's baroque, butter-yellow church in long boats (kyrkbátar), reminiscent in shape of the seafaring vessels used by their Norse ancestors. In 1853 Marstrand painted his immense work Church-Goers Arriving by Boat at the Parish Church of Leksand on Siljan Lake, Sweden (Fig. 4), which shows the arrival of locals on the sandy shore near the church (the same spot where the Midsommar procession begins today), dressed in a rainbow array of distinct, folkloric costumes. Of the event that inspired the painting Hans Christian Andersen noted:

Twelve or fourteen long boats . . . were already drawn up on the flat strand, which here is covered with large stones. These stones served the persons who landed, as bridges; the boats were laid alongside them, and the people clambered up, and went and bore each other on land. There certainly were at least a thousand persons on the strand; and far out on the lake, one could see ten or twelve boats more coming, some with sixteen oars, others with twenty, nay, even with four-and-twenty, rowed by men and women, and every boat decked out with green branches. These, and the varied clothes, gave to the whole an appearance of something so festal, so fantastically rich, as one would hardly think the north possessed.Footnote 24

Figure 4. Wilhelm Marstrand, Church-Goers Arriving by Boat at the Parish Church of Leksand on Siljan Lake, Sweden, 1853. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark. ID: 267218.

Although most Swedes had stopped wearing the colorful variations of local dress that Marstrand recorded as daily costume by 1850, in the Siljan region this practice would continue as late as 1984 and become a staple of Midsommar and other festive or liturgical gatherings.Footnote 25 In an 1852 painting by Swedish artist Kilian Zoll, titled Midsummer Dance at Rättvik (Fig. 5), the artist illustrated how central such folk dress was to the celebration of Midsommar in Dalarna, showing a lively celebration of locals dancing around the Midsommar pole, in a village just up the shore from Leksand (and wearing holiday versions of the costumes unique to their parish, differing in style from those painted by Marstrand).

Figure 5. Killian Zoll, Midsummer Dance at Rättvik, 1852. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. ID: 19489. Photo: Nationalmuseum.

It was the renowned artists Ander Zorn and Carl Larsson, who both moved to the Siljan region a few decades after Marstrand's visit and Zoll's painterly depiction of Midsommar, who assisted in converting the regional customs of the parishes in Lake Siljan to a pattern for the fabric of Swedish nationalism. From his highly eclectic, Viking-revival-cum-baroque stuga (cabin) in Mora, Zorn painted Midsummer Dance in 1897 (Fig. 6), a lively composition, supposedly executed at the stroke of midnight and showing Zorn's local neighbors caught up in the frenzy of a Midsommar celebration, the silhouette of the Midsommar pole erected nobly in the background. When exhibited in Stockholm (where the painting remains today in the National Museum), city dwellers could get a taste of the romantic, “ancient” culture that persisted only a day's train ride to the north of the industrializing urban center. Painted in an energetic, quick, contemporary style, Zorn's canvas made Marstrand and Zoll's earlier, realistic depictions of the Siljan people seem old-fashioned.

Figure 6. Anders Zorn, Midsummer Dance, 1897. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. ID: 18607. Photo: Erik Cornelius / Nationalmuseum.

Around the same time, Larsson and his wife, Karin, made their home, a Falu-red cottage deemed Lilla Hyttnäs [Little cottage on the slag heap], in the charming village of Sundborn. Both trained artists, the Larssons redesigned a humble, worker's cottage into a fantastical collage of Swedish styles, from Norse carvings, Gustavian symmetry, folkloric fabrics, and decorative wall paintings (bonad) paired with an early twentieth-century sensibility toward modern amenities, like electricity and indoor plumbing. Perhaps on an even larger scale than Zorn, the Larssons deeply contributed to the recording and dissemination of “traditional” Swedish culture as they subsumed it into their daily lives. While the Larssons’ embrace of regional culture in Dalarna masquerades as continuity, preservation, and caretaking, their approach as unfettered creators of art that reflected their interpretation of this culture lies closer to Cremona's notion of transformation in the form of a highly theatricalized, folkloric revivalism. The Larssons’ revivalist concept was inspired by preexisting cultural artifacts and traditions that were reformed rather than conserved in original form.

Carl Larsson's dedication to the folkloric is reflected in his distinct watercolor paintings, which were devoted primarily to his family and house, and charmingly illustrated how the family celebrated their version of Swedish identity throughout the year. These works included paintings dedicated to name-day celebrations, Saint Lucy's Day, Christmas [Jul], Walpurgis Night [Valborgsmässoafton] (30 April, when Swedes gather to build immense bonfires and sing out winter), crayfish parties in August and, of course, Midsommar, the jewel in the crown of all Swedish holidays.Footnote 26 As Larsson's paintings were widely exhibited throughout Scandinavia, his personal style became synonymous with a Swedish national aesthetic, and the husband and wife team continue to be credited as the “creators of the Swedish style.”Footnote 27 This style, however, was always anachronistic: an unapologetic palimpsest of their own fine art and craftwork, layering the elegant Gustavian furniture of the upper class, the naïve folk art of rural Swedish peasants and farmers, and scattered antiquities and Asian art all filtered through an Arts and Crafts / Art Nouveau [Jugendstil or “youth style”] perspective that was in vogue at the close of the nineteenth century. Fascinatingly, the Larssons’ house still inspires furniture designs for Swedish giant IKEA, who fund annual research retreats to Lilla Hyttnäs for inspiration.Footnote 28

As Zorn and the Larssons were finding creative inspiration in Dalarna's landscape and folk traditions, back in Stockholm, their friend, historian Artur Hazelius, was engaging a different form of Swedish cultural performance when he founded both the Nordic Museum (which opened in 1907 but had originated as the Scandinavian Ethnographic Collection in 1873) and Skansen, among the world's first open-air museums (1891), to bring a historically imagined version of the Swedish countryside to the city. For more than a decade Hazelius traveled throughout Sweden, buying historic properties including houses, outbuildings, and businesses, and collecting furniture, decorative arts, folk costumes (which were preserved for display, but also copied and worn by park employees), and regional traditions.

On the island of Djurgården in the middle of Stockholm, Hazelius planned Skansen as a village of Sweden in miniature, which currently contains more than 150 buildings from all counties. Hazelius made a place where the regional Swedish past was reorganized as a holistic national saga and could be accessed in that late nineteenth-century present. Literary historian Nicola Humble suggests that in Hazelius's era of ever-advancing technologies and rapid urbanization, “The concern to identify the character of past ages was intimately connected to the desire to pin down and anatomize the present.”Footnote 29 Just as the Larssons and Zorn had borrowed from the past to define their own revivalist mode of Swedish modernity, at Skansen, Hazelius curated a sanitized and romanticized view of a national rurality that glossed over poverty and elevated the festive, via performed nostalgia (in dance, pageantry, handicraft, and costume), over the quotidian banality of farm labor.

In fact, within its first three years of opening, Skansen hosted celebrations introducing Midsommar and Luciadagen, which assisted not only in preserving and disseminating those traditions, but also in transforming them from regional festivals into national and urban celebrations that continue to embody a sense of Swedish national pride in the present day. In fact, Skansen's annual Midsommar is only second to Leksand's in size within Sweden today, and while it pastiches different Midsommar traditions from throughout the country (including a representation of diverse folk costumes), the overall aesthetic, pole, and traditions have been pulled heavily from the Lake Siljan region. Midsommar poles in the southernmost county of Skåne, for example, are smaller, are completely covered with flowers, differ in shape, and do not necessarily follow the same interactive process of raising as in Leksand and other villages in Dalarna.Footnote 30 Many of the same songs and dances, however, are shared nationally (particularly “Små grodorna” [“The Little Frogs”], where participants circle the pole, pretending to be frogs, after it has been decorated, raised, and secured).Footnote 31 As traditions such as the Midsommar pole and its pageantry have spread across Sweden, even to regions where Midsommar was more subdued or celebrated differently, they have helped to codify the various elements of Midsommar into a comprehensive symbol of Swedish national identity.

Scholars Matthew G. Henry and Lawrence D. Berg argue for nationalism as a mode of agency with performative potential, writing “nationalism [is] an ongoing discourse . . . which . . . has a significant effect on the production and reproduction of its citizens’ subjectivities . . . [and] the textual practices of imagination and pointing through which ‘the nation’ is simultaneously remembered and forgotten.”Footnote 32 Hazelius's Skansen acts as a space of historical preservation and imagined heritage and a place that introduced Swedish folk practice to urban Stockholmers, simultaneously performing regional culture while allowing city dwellers and tourists alike to immerse themselves (and even participate) in a kind of monocultural Swedish national identity. This dynamic is an excellent example of a divergent symbol actualized. Skansen can be lauded for its accessibility and inclusion, allowing anyone from any background to participate in cultural production/reproduction—my husband and I had our queer wedding at Skansen in a historic church in 2019—while also providing a more economically affordable opportunity for immersive engagement that does not require travel. In counterpoint, Skansen can also be read as an institution that centers white/Nordic cultural history and customs as the most authentically Swedish. Though Skansen has included exhibits on Indigenous Sámi culture since its beginnings, it largely had excluded the story of immigrants to Sweden, as well as intercultural fusions.

Within the social milieu of elite intelligentsia in late nineteenth-century Sweden, author, playwright, painter (and undeniable anti-Semite) August Strindberg was also close friends with Hazelius when Skansen was being planned and constructed. While Hazelius was working on his museum of living history, Strindberg published Svenska folket (1881–2), a history of Sweden that focuses on its common citizens rather than monarchal influence and legacies of sovereign power. Although Hazelius saw himself as a cultural historian, he was less concerned with the “political reform” that guided Strindberg's work.Footnote 33

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Larssons, Hazelius, and Zorn all ran in the same circle along with Strindberg, and he corresponded with all of them, even asking Larsson to provide the illustrations for Svenska folket. While I cannot corroborate that Strindberg ever visited Dalarna at Midsommar, he certainly would have been familiar with the traditions through the work and correspondence of his artist friends, and I imagine he would have gained such knowledge through conversations about Skansen's festive schedule, with Midsommar as the living museum's three-day main event each June. Because Skansen is open to the public, today attendees can interpret the celebration however they wish. However, preexisting assumptions about the origins of the holiday and the Midsommar pole as pagan could lead to an unsubstantiated theory that the pageantry is rooted in cultural continuity, when in fact the celebration is contingent on practices that include both preservation and change. This epitomizes the complex and manifold possibility for interpretation inherent in a divergent symbol.

Midsommar and Pagan Misinterpretation

Contemporarily, the Sweden Democrats Party has taken to politicizing Swedish festive celebrations, like Midsommar, by dubiously linking them to pagan origins and whiteness.Footnote 34 This fabrication has its roots in the cultural production of the nineteenth-century Nordic Renaissance.Footnote 35 In his play Miss Julie, Strindberg sets the action of the play on Midsommar's Eve on a country estate in rural Sweden. Critics often link Strindberg's Midsommar setting of Miss Julie to “pagan” revelry as a symbol of fertility, sexual celebration, and the overwhelming lust of the main characters, Julie and the valet, Jean.Footnote 36 One translation even adds the apocryphal note, “The action takes place on Saint John's night, the mid-summer festival surviving from pagan times.”Footnote 37 While the origins of Midsommar in Sweden are impossible to trace with exact certainty, it is most likely that the celebrations developed as a collage of local customs paired with traditions imported from the Continent, specifically Germany in the Middle Ages. For example, the Midsommar pole is a cultural reframing of the German Maypole (der Maibaum), which although of pagan origin (with unsubstantiated claims as a symbol of the phallus/fertility),Footnote 38 had certainly taken on Christian connotations by the time it was first raised in Sweden.

A 1689 record of Midsommar celebrations in the Swedish town of Björksäter relates that Midsommar poles were banned because the symbol was associated with the heightened sexual revelry and debauchery of the town's youthful population.Footnote 39 While according to a 2015 study, it is true that more babies are conceived on Midsommar's Eve than at any other time in Sweden, historical origins of the holiday in pagan solstice revelry, sexual debauchery, and sacrifice, as have been portrayed in recent films including Ari Aster's Midsommar (2019) and Robert Eggers's The Northman (2022), remain unproven. In fact, official, public celebrations remain wholesome family affairs that simultaneously celebrate both the liturgical and agrarian calendars and a performance of folk life as a national ethos of Sweden—even if more intimate celebrations may maintain an air of romance, hedonism, and carnal desire.Footnote 40

The Midsommar pole celebration was moved from May Day to the end of June not only because of Saint John's Day and the solstice, but also because Sweden was still too cold and barren to celebrate in early May as with their southern, Teutonic neighbors.Footnote 41 In the ongoing performances of Midsommar at Skansen and in Leksand, however, this history is pushed aside, if not intentionally displaced (performing a kind of cultural continuation that was formed only through a cultural transformation of scant factual evidence), demonstrating how the rise to national identity in the late nineteenth century allowed for a curation of symbols that maintained their purpose and power as distinctly Swedish, rather than as records of migration or intercultural influence. Likely, though hard to pin down concretely, a keen interest in pagan Sweden in the nineteenth century is a possible origin of false Norse/Viking associations with the Midsommar pole, which continue to this day (an incorrect assumption that, admittedly, I myself held previously).

The Nordic Museum suggests that even though the celebration of Midsommar is recorded in the Icelandic sagas (among the extremely limited written records of the Viking Age to be passed down), such sources must be approached with the caution that “pre-Christian connections [to Midsommar] are highly speculative.” One of the first documented descriptions of Swedish Midsommar appears in Olaus Magnus's Historien om de Nordiska folken (1555), which describes the festive events of Saint John's Day Eve, when crowds gathered “in the squares of the cities or out in the open field, to dance merrily there by the glow of numerous fires, which are lit everywhere.”Footnote 42 While bonfires are typically less central to official Midsommar celebrations today, such as in Leksand or at Skansen (reserved instead for Valborgsmässoafton on the last day of April), it is not uncommon for them to be built at more intimate, private gatherings. (Strindberg describes such a bonfire party in his short story.) One can imagine, however, how descriptions such as Magnus's invoke if not promote apocryphal pagan origins.

Leksand's annual Midsommar pageant is visceral and truly feels ancient—an embodiment of cultural continuity—when in fact its current form is one of cultural transformation, taking place at Sammilsdal and in this form only since 1939 (when it was moved from the center of town, where the other Midsommar pole marks the start of the procession). While national pageants that embraced folkloric customs, music, and costumes were ubiquitous on both sides of the Atlantic in the first half of the twentieth century (often converging in the form of world's fairs and exhibitions), one cannot help but notice that the schematic establishment of Leksand's celebration took hold only three years after the Nazi's grand Thingspiele pageant at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. This performance, entitled “Olympic Youth” and envisioned by Adolf Hitler's propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, relied upon classical and Norse symbolism to promote white supremacy, even inventing the torch relay from Olympia in Greece to Berlin, performing a dubious link from Hellenic Aryanism to the pagan tribes of Northern Europe.Footnote 43 While I have yet to uncover a direct link between the Nazi Thingspiele (named after ting, the Norse and medieval ritual gatherings of Scandinavia) and the pageant at Leksand, when read in geographic, cultural, and temporal contexts, it is important to consider how events such as Midsommar have been acculturated for autocratic and jingoistic manipulations of white nativist nationalism, in the past and the present.

Lucia: Paganism/Nationalism/Imagined Histories

Much as with Midsommar, it was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that a trend for making false pagan connections to other Christian celebrations, like Luciadagen, took hold. This was in an effort to invent native, identity-making histories that stretched into the ancient past as wars saw Europe split and reform into different nation-states and a “nationalization of the masses” swept the Continent.Footnote 44 In Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, the construction and curation of these national folk histories as a form of cultural continuation and resuscitation became of particular interest in scholarly circles that had been almost singularly dominated by the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean and Near East. Norse myths and the Viking pantheon were not rediscovered until the end of the eighteenth century, but soon after resulted in a flowering of the so-called Nordic Renaissance, where these distinctly Scandinavian stories provided a counterpoint to the neoclassicism driven by Greco-Roman aesthetics and ideals that had been sweeping Europe since the 1760s.Footnote 45 Authors and artists alike were inspired by the tales of the Aesir (the principal Norse gods) and their Viking ancestors, and soon the ancient landscapes of Sweden and its Scandinavian neighbors were reanimated with these colorful stories.

For example, eleventh-century historian Adam of Bremen chronicled the site of a major Viking temple at Gamla Uppsala (south of Dalarna), decorated with an immense golden chain and dedicated to the divine triad of Odin, Freyr, and Thor. According to Bremen, pagan sacrifices were held every nine years in a sacred grove of trees adjacent to the sacred building.Footnote 46 Though the site is certainly ancient, played host to medieval ting, and held a larger wooden building, whose foundations were uncovered by recent archaeological work, beneath its early medieval Christian church, there is no corroborative evidence to prove that the temple existed or that such gruesome sacrifices occurred. In fact, historian Anders Hultgård suggests that rituals such as those described would never have taken place as a public spectacle at Uppsala.Footnote 47 Folklorist Hilda Ellis Davidson cautions scholars of Old Norse history to refrain from “bas[ing] wild assumptions on isolated details.”Footnote 48 Nonetheless, in 1915 Carl Larsson unveiled his large-scale painting Midvinterblot (Midwinter Sacrifice) as a permanent decoration in the central staircase of Stockholm's National Museum. The megalographic painting interprets the great temple of Uppsala with its golden chain and a nude king preparing himself for a ritual sacrifice. Although poorly received for its anachronistic, almost orientalist aesthetics, Midvinterblot is the perfect example of a national symbol that blurs Sweden's murky history and mythology as an allegory for a modernist approach to nationalism and a national aesthetic as driven by a reinterpreted past. By taking center stage in a building dedicated to Sweden's national story as represented through visual art, Larsson's immense painting is far more affectively performative than it is a document of imagined Norse history.

Midsommar (and its customs) can be read similarly to Larsson's painting as a palimpsestic symbol of Swedishness, though its hazy origins and late nineteenth-century codification (by people like Hazelius) make it almost impossible to trace. Luciadagen, however, which is celebrated each 13 December (purported to be the darkest night of the year in the Julian calendar) as a counterpoint to Midsommar's celebration of the sun, provides a more recent example of a Swedish Christian holiday that has sometimes been co-opted by the romance of Norse mythology and ritual culture and transformed into yet another imagined history.

Lucia processions are held throughout Sweden in churches, schools, and community centers, in addition to a national television broadcast with an official Lucia, and takes place in the early morning hours of 13 December, before the sunrise.Footnote 49 Lucia, patron saint of the blind and “bearer of light,” wears a crown of candles on her head and is attended by maids in white robes, often by stjärngossarna (“star boys” or Epiphany singers) in conical caps, and sometimes by a group of jultomtar, the woodland gnomes who traditionally bring Swedish children Christmas presents on 24 December.Footnote 50 Legend tells us that the martyred saint's crown is a recreation of the “historical” moment when Lucia wore candles on her head to deliver food to persecuted Christians who were hiding in Rome's catacombs in the third century ce.Footnote 51 In Sweden, Lucia's coronet of live flame is reminiscent in shape to traditional bridal crowns (brudkronor), which are owned by local parish churches and loaned to young women for ceremonies, probably originating as early as the medieval period. The wearing of a crown thus symbolizes not only Lucia's saintly divinity as a halo, but also her bridelike virginity, additionally emblematized by her long, white gown.

While it is entirely unclear how an Italian saint was migrated to Scandinavia as a cultural symbol, one can imagine that she may have been a creative adaptation of sacral art observed on the Grand Tour, since Lucia first appeared in the homes of the wealthy and noble. The first recorded Lucia procession in Sweden took place in the eighteenth century, but in 1893 public processions at Skansen spread the popularity of the holiday, and by 1927 the first public contest was hosted in Stockholm to select a Lucia (Fig. 7).Footnote 52

Figure 7. A group of young Swedes dressed in the costumes of Lucia and her attendants in Gothenburg, Sweden, ca. 1900. Photo: author's collection.

Whereas the symbolic Lucia is an import of the baroque south (though medieval cathedrals and churches throughout Sweden bear the vestiges of pre-Lutheran, Roman Catholic aesthetics), the mystical quality of the processions—a performed embodiment of light defeating the darkness—has been linked to Norse mythology. Terje Birkedal writes:

Some [. . .] believe that the celebration of Saint Lucia Day may have its origins in Norse pagan conceptions of the struggle between light and darkness. One 19th-century Lutheran pastor suggested that Saint Lucia was really Freya, the Norse goddess “dressed up” as a Christian saint. . . . Freya was known as the “shining bride of the gods.” Others link the Saint Lucia celebration to the ancient worship of Frigg, the wife of Odin, who . . . gave birth to Balder, . . . the Norse god of light.Footnote 53

Although this historical linking of Lucia to the Aesir is most likely more of a Romantic Wagnerian-style fantasy than fact, Birkedal points to the nineteenth-century desire to connect contemporary Swedish identity with the recently uncovered past, setting the nation and Scandinavia apart from the rest of the Continent at the dawn of the Nordic Renaissance.

In 1930s Germany, Hans Strobel, a historian who worked for the SS-sponsored Working Collective for German Folklore, began transforming Christian Christmas customs for the Third Reich. Strobel and his colleagues attempted to secularize the festive season by introducing “‘Nordic’ Christmas customs and clarif[ying] the links between pagan solstice festivities and the ‘return to light’ rituals.”Footnote 54 Fascinatingly, it was just before this period that Lucia became a day of national importance in Sweden, with Stockholm proclaiming its first official Lucia in 1927, an event that would only grow in popularity with an annual parade in Stockholm by the 1930s; Lucia was transformed from a festive, regional figure into a national icon (Fig. 8).Footnote 55 Though it is impossible to trace a distinct link between the genesis of Stockholm's celebration and Strobel's fascist appropriation of Nordic cultural history, a decade later in Denmark, Lucia became the embodiment of symbolic divergence when in 1944 the Danish resistance imported Lucia and held its first procession as a sign of “light and hope” during the nation's Nazi occupation.Footnote 56

Figure 8. A frenetic photo of the large public, official Lucia procession parade in Stockholm, ca. 1932. Photo: author's collection.

Although Luciadagen originated as a Christian religious festival, today it is primarily a secular celebration of the winter solstice and Christmas, resulting in a profusion of Lucia-themed decorations and products for purchase. In fact, in Sweden, Lucia represents a period of holiday festivities and consumerism as much as Santa Claus does in the United States.Footnote 57 In 2016 the Swedish department store chain Åhléns capitalized on Lucia with an online advertisement featuring a young Black boy sporting the traditional crown of candles and a white robe. At first, this contemporary reinterpretation of such a traditional symbol may seem in line with Sweden's reputation as a progressive, social welfare state, with a commitment to inclusion and representation and one of the best track records for legal immigration. Annually, Sweden welcomes an average of 247,806 refugees each year, making it the country with the fourth highest number, after Germany, France, and the United States, but with a markedly smaller population of only about ten and a half million.Footnote 58 Unfortunately, Sweden's openness to immigration does not always equal universal acceptance, and the advertisement for Åhléns was met online with racist and homophobic comments that led the marketing department to pull the ad altogether. Exponentially more Swedes reached out to support the boy, and a campaign with the hashtag #jagärhär [“Jag är här,” I am here (for you)] gained traction.Footnote 59 Across Sweden, children of color, both citizens and immigrants, participate in Lucia processions each year, but it was the push against the iconic blonde, blue-eyed girl as Lucia, as first widely represented by Carl Larsson and his contemporaries, that was the last straw for those who espouse xenophobic tactics and racist rhetoric to police Swedish cultural traditions and claim them as exclusively white and Nordic.

The shameful incident surrounding Åhléns's Lucia campaign is an example of Sweden's complex political climate, demonstrating how its global reputation for social progress, inclusion, and diversity can be clouded by a history of remote isolationism, both in terms of its geographical position in the world and the agrarian, rural economy that dominated most of its history. Lucia is, in fact, a relatively new celebration born of cultural migration, if not appropriation, but it was only through the Viking revivalism of the 1830s, followed by the Romantic cultural reframing and dissemination by the likes of the Larssons, Hazelius, and Zorn, that such regional traditions were given weight, transforming them into public archetypes of Swedish nationalist pride.Footnote 60

Though the origins of Midsommar are older than those of Luciadagen, both holidays were nationalized in roughly the period discussed in this essay. As Sweden has grown and changed over the past century, both holidays have endured as divergent symbols, depending upon the political views of the participant/critic. Regardless of their relatively recent transformations, together Midsommar and Luciadagen retain an air of old folk culture, splitting the calendar year in half, using specific, ingrained aesthetic and practices. Just as the illuminated crown, white robe, and red sash are essential to the visual vocabulary of Lucia, regional folk costumes invent heritage through an imagined history of Midsommar.

Wearing Midsommar: Folkdräkt and Symbolic Divergence

Midsommar's machinations as a divergent symbol, whether as a form of inclusive cultural transformation or as an exclusive appropriation of cultural continuity, depend on independent symbolic elements that are essential to a codified whole of the celebration's pageantry. Though the Midsommar pole may be the best known of these “historic” symbols, folk costumes have perhaps played an even larger role in defining the national role of the holiday—and even Swedish identity as something that can be identified, claimed, and worn both individually and collectively. Whereas the first representation of regional Swedish folk costumes were probably in the form of naive bonad paintings from the eighteenth century, it was not until the Romantic period that Zorn and his contemporaries began recording them in a realistic, contemporary style.Footnote 61 So committed were Zorn and the Larssons to the quickly developing new image of old Sweden that they collaborated with Gustaf Ankarcrona and Märta Palme Jörgensen (founder of the Swedish Women's National Costume Association, who had relocated from Stockholm to Dalarna) in 1902 to design a “new” national folk costume, in blue and yellow with embroidered daisies (worn with a white blouse), inspired by the Swedish Jugendstil that was in vogue at the time.Footnote 62 The intention of the costume was to provide not only a stylish reinvention of the past, but also an option for Swedish women in provinces where traditional folk dress had not been passed down through the generations, as it had been in the villages and towns surrounding Lake Siljan.Footnote 63

In the Introduction to Svenska folket, Strindberg argued that folk costumes were not “primitive” garments that had been preserved and passed down, but rather a process that developed and changed through the ages, depending upon technology, functionality, and style.Footnote 64 In fact, in his short story “In Midsummer Days” (1913), Strindberg describes a poor young woman stitching an apron on Midsommar's Eve for her daughter to wear the next day. The story, set on an “island,” is likely inspired by Kymmendö, an island in Stockholm's archipelago where Strindberg spent time in his youth. “In Midsummer Days” not only corroborates Midsommar as a regional celebration about to take place, but also situates the making of the folk apron as an ongoing cultural practice reflective of contemporary technology, as the mother employs “a sewing machine.”Footnote 65 This clash of the old and the new, a simultaneous looking back while moving forward, epitomizes the power of folk costumes in Sweden as divergent symbols of social performance (Figs. 9, 10).

Figure 9. A large group of women wearing variations of Swedish folkdräkt representing various parishes, late nineteenth century. Photo: author's collection.

Figure 10. Leksanders in the traditional dress of their parish, second half of the nineteenth century. Photo: author's collection.

Folklorist and Scandinavian fashion historian Carrie Hertz argues that “dress [is] a form of daily artistic communication that is realized in moments of social performance.”Footnote 66 In Sweden, Midsommar epitomizes one of these “moments.” While the folk costumes of Dalarna certainly exist outside of Midsommar and may be worn for other festive occasions throughout the year—traditionally the costumes varied depending on the season and the holidays of the Lutheran liturgical calendarFootnote 67—it is hard to imagine Midsommar in Leksand (or Skansen, or numerous other public celebrations throughout Sweden) without the presence of folkdräkt.

The collaborative design process among the Larssons, Zorn, Ankarcrona, and Jörgensen is a case study that actualizes scholar Henry Glassie's definition of tradition as a “creation of the future out of the past . . . in a process of cultural construction.”Footnote 68 By the mid-twentieth century their new blue and yellow costume had almost been forgotten, in part because Jörgensen's dogmatic perspective had linked national dress to the fascist New Swedish Movement, even as the nation remained neutral during the First and Second World Wars.Footnote 69

Decades later, in 1983, Queen Silvia of Sweden wore a custom version of their original costume on Sweden's National Day, ushering in a new period for the costume to be produced, worn, and celebrated (a tradition continued annually on 6 June by the women in the royal household). Queen Silvia had married into the Swedish royal family seven years earlier (née Silvia Renate Sommerlath), having grown up in Germany, the child of a German father and a Brazilian mother. Silvia's decision to revive the costume (whether personal or political) is yet another example of a divergent symbol. On one hand, as a new Swedish citizen and one-time immigrant, the queen's sartorial choice personified a welcoming access to Swedish cultural identity. The costume is made available to everyone who can afford it, and from Stockholm to Uppsala to Mora, I saw different versions of varying quality and cost readily available in shops. This was the very costume that I observed many young women of color sporting at Leksand's Midsommar. On the other hand, the exclusionary and nativist origin of the costume as a result of Jörgensen's politics renders it troublesome, though arguably salvageable through its cultural reorientation. Moreover, the contemporary neofascist Sweden Democrats have taken to wearing the national costume along with regional folkdräkt as a sartorial symbol of their right-wing, populist politics. In 2010 the leader of this controversial party, Jimmie Åkkeson, opened Parliament in a folk costume from Blekinge, accompanied by his girlfriend in a version of the 1902 tricolor national costume. The Sweden Democrats’ party platform is defined as “social conservative with a nationalist foundation” and criticizes immigration and multiculturalism as detrimental to the preservation of national heritage.Footnote 70

In counterpoint, in 2009 a group of Stockholm artists, Fuldesign, reinvented the national costume to include a hijab, making the costume culturally equitable for the modern population of Muslim Swedes and expanding the notion of cultural heritage. In her notable work on Nordic folk costume, Lizette Gradén invokes folklorist Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett to unpack heritage as a practice, writing: “When understood as a situated embodied heritage practice—a mode of contemporary cultural production with recourse to the past and a more or less articulated wish to influence how history is shaped in the future—folk costumes become avenues to understanding racial and class issues and tools for negotiating identities, diversity, and the (re)creation of place.”Footnote 71 Heritage practice aligns with a cultural product that allows for continuance and transformation, creating adapted folk costumes, like Fuldesign's, as cultural objects that ignite new, more inclusive traditions for the future while maintaining a respectful acknowledgment of the past as a font of inspiration rather than a limitation.

The performance of wearing folkdräkt allows people to feel they are part of the distinctly Swedish fabric of Midsommar, to engage in a historical masquerade both as a part of the group and as an individual. Costume pieces are accessible to purchase at discounted prices in handicraft stores in the towns and villages around Lake Siljan, though families are also known to pass down handmade traditional garments through generations. Nonetheless, while I did observe people of various races and ethnic backgrounds in folkdräkt at Leksand (though admittedly a relatively small number; Fig. 11), there was no presence of folk costumes from the other cultures that richly diversify the Swedish state, such as Balkan or Middle Eastern. Yet Sweden prides itself on a constitutional Integration Policy (1997), celebrating difference, ethnocultural diversity, and a Diversity Charter (2010) that promotes “cultural, demographic and social inclusion.”Footnote 72

Figure 11. A family attends Leksand's public Midsommar celebration wearing traditional folkdräkt of that parish. Photo: author.

Conclusion

In his preface to Miss Julie (1888), Strindberg describes Julie and Jean as “modern characters, living in a period of transition . . . torn between the old and the new.”Footnote 73 This sentiment perfectly embodies the role of Midsommar at Leksand as a divergent symbol. For politically progressive Swedes, Midsommar has been adapted as a cultural gathering that celebrates a national communitas without pervasive patriotism. The pageantry is rich with tradition, even if it is not as ancient as it may first appear, and the spirit of the event is as much a celebration of the summer season as it is about national identity. On the other hand, political parties like the Sweden Democrats, alongside other white supremacist groups who employ Norse symbols as part of their hateful propaganda, may attempt to claim Midsommar and its components—folk music, dance, and costumes—as a performance of an imagined Nordic heritage rather than a historical performance that takes great liberties.

Alarmingly, during the general election for Swedish Parliament (Sveriges riksdag), in September 2022, citizens voted in the Sweden Democrats at 20.5 percent of the total body, making them the second largest party in the right-leaning government headed by the Moderate Party and led by Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson.Footnote 74 Following this rise in representation, SD head Åkkeson noted that the new government would be a “paradigm shift” and comprise “order, reason and common sense,” leaving the reader to understand the underlying inferences as a fascist vision of anti-immigration and the legalization of intolerance.Footnote 75 In response, the Nobel Foundation announced that Sweden Democrats’ leaders, including Åkkeson, were disinvited from its annual 2022 banquet in Stockholm—a celebration that epitomizes the links among Swedish politics, culture, and humanism on the global stage.Footnote 76 As this rift continues to unfold within Sweden, I am reminded of the complex and even violent contestations that lurk beneath the surface of cultural traditions—like the Nobel banquet or even Midsommar, that are, perhaps incorrectly, understood to be apolitically neutral celebrations of national importance—and the sanitized theatricalizing of a de facto Swedish identity.

Midsommar in Leksand invites an ambivalent reception of an imagined and performed text that fluidly conforms to the divergent, affective, and individual desires of the observers and participants alike. As demonstrated in this essay, Swedish Midsommar is not without a complex and still emerging history that is often clouded by its festive spirit; yet Leksand's pageantry felt joyous and inclusive nonetheless. Granted, as a white, queer American, my positionality and perspective allowed me to participate largely under the radar, but I felt safe; moreover, for a national celebration it lacked the anger, fanaticism, and threat of violence and jingoism that so often bubbles under the surface of patriotic gatherings in the United States.

Sweden's past is undoubtedly marked by oppression, injustice, and an ongoing intolerance for difference, just like any country's, but its older national history and turn to social welfare in the postmodern era makes it feel a world apart from the violent history of colonization, enslavement, genocide, cultural theft, and marginalization that systemically plagues the still relatively “young” United States (as opposed to Turtle Island and its ancient Indigenous culture and history). While both nations were informed by a fervor for national identity that swept the landscape of the late nineteenth century, Sweden seems to have settled into a place that largely favors a state value system based on the ecumenical value of life over global power. While attending Leksand's Midsommar I was nagged by the question of why our own national celebrations and symbols seem so fraught, but perhaps this is because the divergence in American culture has reached the point of catastrophe rather than dissent. The red, white, and blue of Old Glory on the Fourth of July are inherently a symbolic celebration of settler colonialism, bloodshed, and persecution as much as freedom. This American approach stands apart from the communal performance of Midsommar: the elation of watching yet another year pass, a victory over winter as the flower-bedecked pole is erected to the sky, reminding us that—in the midst of a global pandemic, the rise and fall of political regimes, an elevating recession, a planet in crisis and once again under the threat of nuclear war—we, like the turning of the seasons, still persevere.

Sean F. Edgecomb is an Associate Professor and Resident Director of Theatre at Fairfield University, Connecticut. His first book, Charles Ludlam Lives! was selected as part of the Big Ten Open Books collection to promote equity and inclusion. His edited collection, The Taylor Mac Book, was recently released by University of Michigan Press. He also creates original queer folk art under the sobriquet of Peter Kunt and curates The Gallery for Ghosts in the attic of his 1698 former-tavern home in Norwichtown, Connecticut..