So writes “M.T.” upon witnessing Anna Renzi (ca. 1620–after 1661) perform cross-dressed as the character Ergindo in the 1644 Venetian opera La Deidamia at the Teatro Novissimo. Indeed, “M.T.” was so captivated by Renzi's voice and presence on the stage that, he proclaims, “if as Ergindo she sighs, a celestial aura breathes, so that everyone here is blessed and nourished by the nectar from above, and her beautiful face opens, a delicate face, almost a bright flame, and with a clear flash inflames souls.”Footnote 2 This poem is one of several in Le glorie della signora Anna Renzi romana (1644), a booklet of poems dedicated to Renzi and expressing the power she exercised over spectators through her performance. Following Claudio Sartori, Ellen Rosand avers that Renzi was “the first ‘prima donna’ in operatic history” which is a status for which she achieved universal acclamation.Footnote 3 This acclaim was both a product of the critical response elicited by Renzi's luminous stage persona and a negotiation of gender in the marketplace. As such, Renzi pioneered the profession, and her performances inaugurated several of the first opera houses in Italian-speaking lands and beyond. As I demonstrate, the extraordinary sound of skilled singing granted her the privilege of autonomous decision making and movement within the city and beyond its borders. Due to her personal autonomy and professional performance, I posit that Renzi challenged societal norms and influenced perceptions of women and their agency in the early seventeenth century.

My analysis follows the theoretical framework of Judith Pascoe, who created an initial road map for accessing and examining the sound emissions of Sarah Siddons's (1755–1830) dramatic roles through audience accounts. Attempting to experience Siddons's voice directly, Pascoe combines contemporary descriptions with auditors’ testimony. In this, she unites “old-school archival work with new-school performance theory,” respecting “both material specificity and epistemological uncertainty,” to resurrect Siddons's voice using critical theoretical frameworks by media theorists and sound historians.Footnote 5 While Pascoe's study remains speculative, her approach to the indelible impact of Siddon's spoken voice applies to the reception of Renzi's virtuosic singing sound. Like Siddons, whose sound made her “seem so staggeringly original,” Renzi had a highly developed and specialized delivery.Footnote 6 Her body in performance transmitted the repertoire of Roman singing technique and contemporaneous acting priorities. Descriptions of her performance and person offer ways to reconstruct her impact within the social milieu upon which I elaborate.

Much of my theorizing based in speech-act theory is informed by the invaluable work of Judith Butler, from whose work I have gained so much. However, I diverge from Butler's stance that cross-dressed stage performance does not qualify as a social force able to impact gender performativity beyond theatrical performance, as Butler has written about cross-dressed and drag performance when such “parodic repetitions . . . become domesticated and recirculated as instruments of cultural hegemony.”Footnote 7 I specifically do so in the case of Anna Renzi. This is because I characterize Renzi's cross-dressed stage performance as part of an assemblage of identity that included her prototypical embodiment of female agency and virtuosic mastery as a professional singer in commercial theatres. On at least three levels her performance of gender represented an exemplary, and discernable, synthesis:

1. as one of the very first operatic female performers to perform cross-dressed, thereby undermining concepts of gender fixity;

2. as an independent woman forging the new status of professional operatic female artist on commercial stages; and

3. in her everyday performance of self as an independent woman with agency in a rigidly patriarchal culture.

All these aspects enacted a notable social force when perceived in as a performative totality whereby, in her time, Renzi's very existence as a social being was subversive.

Commercial theatres first developed in Venice, where they were established circa 1580.Footnote 8 On one hand, while performance in commercial spaces rendered their resonant bodies sexualized objects for purchase, mercantilism also offered prima donnas the opportunity to pursue careers that normalized their professional status. Within the urban complex, performance spaces involve an interrelationship of participants at the event, including audience members, performers, and workers such as stagehands. As Antonio Cascelli posits, “places allow a reconciliation between ourselves and the world, which is ritualised in the theatre (both as architecture and as performance),” the results of which are carried out into the city.Footnote 9

The new dramatic form emerged amid a burst of inter-European trade, mass communication, and commercial industry. Venice, furthermore, was a travel destination for Europeans during carnival, where the lively exchange of cultural ideologies was a feature. Chris Rojek links “taste cultures” to the rise of industrial capital and urban populations during the shift from royal court culture to urban popular culture.Footnote 10 New technologies, like Giacomo Torelli's (1608–78) arsenal and stage machines arose, and new groups like the Incogniti literati, whom I discuss in the next section, formed as part of this shift. The paradigmatic transition from feudal to mercantile socioeconomic systems destabilized the ideal of the patriarchal state along with the essential fixity of masculine and feminine identities.

The involvement of women who self-sufficiently conducted their economic and personal affairs in traditionally male spheres, like publishing and public performance, was anomalous. The rise of published women writers as well as professional women stage actors and singers, moreover, introduced a new social type. The performance of gender as a professional woman singer in city life evokes Erving Goffman's performance of social roles in everyday life.Footnote 11 I suggest that, over time, the professional women's performances generated theatre that changed conceptions about gender onstage, as their movements through Venice's cultural milieux foresaw transmutation in the performance of gender in everyday life, thereby altering normative attitudes based in the concept of the inherent inferiority of women to men in Venice's ancient patriarchy.

Renzi first appeared in the cross-dressed servant role of Lucinda/Armindo in Chi soffre speri (1639) for a private audience at the French Embassy in Rome.Footnote 12 This early opera was labeled a “comedia” and included characters with commedia dell'arte names like Zanni and Coviello. However, a papal ban on women performing on public stages in Rome, despite their having received exceptional training, compelled them to travel to Venice to pursue professional careers.Footnote 13 As Nino Pirrotta substantiates, most early opera companies originated in Rome.Footnote 14 Venice's San Cassiano theatre, established originally in the 1580s to showcase commedia dell'arte troupes, hosted the first public opera, L'Andromeda (1637), for a paying audience. The popular success of Venice's newly establishing opera industry, with its virtuosic singing stars, soon rocketed. As it communicated ideas about Venice's “political culture,” Rosand conveys, opera “parodied its mores (for example, in manner of dress and carnival behavior) and its characters (courtesans, procuresses, gondoliers, etc.).”Footnote 15

Renzi benefited with the timing of her arrival on the commercial stage, and her debut performance in the lead role of La finta pazza (The Feigned Madwoman) in 1641, just four years after L'Andromeda, inaugurated the opening of Teatro Novissimo, the first commercial theatre custom-built for and dedicated to operatic production. Word of the astounding production traveled swiftly. A subsequent publication titled “Il cannocchiale per La finta pazza” [The opera glasses for La finta pazza] by Incognito member Maiolino Bisaccioni (1583–1653) characterized Renzi as “a young woman . . . brave in action and as excellent in music . . . cheerful in pretending insanity but wise in knowing how to imitate while being modest in all other ways.”Footnote 16 When Florentine Prince Mattias de’ Medici (1613–67) heard about these novel Venetian productions, he traveled there during the 1641 season to work on a production personally.Footnote 17 On 5 March 1645, Mattias attended a performance of La finta pazza. (I outline Renzi's influential journey to Florence to introduce the new form in the later section “Sound and Vision Travel On.”)

The experimental genre was replete with hybrid interlocking elements like polyphonic madrigals and monadic recitative/aria, where recitative as recited text was interrupted by embryonic arialike musical forms like ariosi all set into a continuous musical and dramatic whole, where acting was equally as important as singing. The music fluctuated in a liminal sonic space between modal and tonal paradigms. Comedy was mixed with heroic and tragic elements, and improvisation intermingled within musical and dramatic structures.

Despite a stipulation in the original contract for Teatro Novissimo that it should produce “only heroic works in music and not comedies,”Footnote 18 in practice, the operas produced there featured both comic and heroic elements. Stock characters and other overlapping commedia dell'arte elements in La finta pazza, for instance, included the Nurse, the Captain of the Guard, and Buffoons, all employed with libidinal humor and scatological allusions. Stock comic and lower-class characters, furthermore, such as “princely gardeners,” servants, warriors, old men, the comic old woman, as well as the hermaphrodite were all present in early Venetian operas.Footnote 19 Such genre morphology encompasses a fluid drift at the borders where styles mix and borrow—in this case, at the interstice of commedia dell'arte and dramma per musica, as opera was called in the period. Nevertheless, the differentiation between the older commedia dell'arte and the new opera genres precipitated a shift in cultural status whereby the all-sung operas rapidly took priority. By the eighteenth-century comedic aspects had been abolished from heroic opera seria.

Chris Rojek argues that in reading societies, galleries, coffeehouses, assembly rooms, debating clubs, and concert halls, new “taste cultures” arose that replaced royal patronage and within which celebrity culture was born.Footnote 20 From the 1660s to the 1670s, due to power shifts between royal societies and court systems, clarifies Rojek, “taste cultures multiplied in European society,” producing greater demand for specialized and expensive cultural products as “lucrative, objects of commerce.”Footnote 21 I nudge Rojek's date back from the 1660s to at least the 1640s, with the burgeoning popular success of public theatre in Venice and especially with the newly forming commercial opera industry. This nodal time frame, in the transition from Renaissance to baroque taste cultures, occurred just as Renzi was performing. As the face of a new movement, Renzi in her stage work synthesized a betweenness indicative of the shifting cultural taste, her presence as a celebrated prima donna presenting a new set of meanings for audiences to unpack.

Renzi embodied sexually ambiguous characters onstage while subverting conventional gender codes within the cityscape to fashion a new social identity. She was a prototypical stage performer in her performance of very early operatic roles written specifically for her. Offstage, she modeled how a professional woman singer could successfully comport herself in society to avoid social condemnation as a woman of ill repute. Her travels and success proved her ability to steer her career and business dealings deftly while pioneering a new profession for women.

The commercial theatre provided a liminal stage upon which to experiment with expressions of sexuality and gender for a plurality of economic classes and genders. Transvestite performance offered a specter of freedom of choice to performers and attendees constrained by regulated gender norms. Performing typicality and singularity in transvestite performance, embodying the juxtaposed aspects of vulnerability and strength, experience and innocence, constitutes what Joseph Roach calls an “ontological subversion” of gender.Footnote 22 (Later, I delve into how cross-dressing was linked to seventeenth-century ideas of hermaphroditism, especially when women engaged in it.)

When Renzi performed virtuosic feats, she called a new social subject into being. As Beth and Jonathan Glixon impart, “The role of women singers themselves . . . was particularly critical: it was through their voices (rather than those of the castrati) that many notions about gender and sexuality were disseminated to Venetian audiences.”Footnote 23 Renzi proved gender norms for women transposable by exceeding them. Her celebrity status wrought her an influential position as a role model for women as her performance of gender and identity in everyday life helped to reformulate how women could live. She accomplished this by balancing a paradox: acting as a reserved and virtuous woman adhering to the imperatives of female silence and submission to male control, even as the gender she performed onstage and her agency in everyday life contested them.

Significantly, “[o]pera also changed the lives of the women who chose to perform it, perhaps even more than for male singers of this time: a select few, through their special appeal to the public, earned enormous sums and achieved the status of ‘diva,’” write the Glixons.Footnote 24 As I demonstrate, male authority allowed Renzi's performance. But she also won public approval from a diverse crowd, garnering broad public exposure beyond hegemonic control. By arousing unfulfilled desires, divas embodied what Rosalind Kerr terms “commodity fetishism.”Footnote 25

Even as opera producers commodified women performers and their sexual allure, the possibility of commodification itself provided women with a new profession to pursue. Certainly, the cross-dressed diva's demonstration of gender variability meant that what was said (or sung) passed through her performing body to betray its understood “truth” by breaking the constative promise of biologically determined gender. In performance, the physical and psychological force of her somatic resonance burgeoned extralingually as an illocutionary force beyond the logic of the text: learned but done differently by the performer. This is so, even if learned gestural conventions and the librettist's text constituted the promise of female subjugation. In this way, the text as expressed by the compelling singer in performance offered diverse meanings to the receiver. As a professionally trained and sonically potent performer, and as a self-reliant businesswoman, Renzi performatively reworked gender norms to become something new in readable ways: a liminal surface on which to contemplate compelling possibilities.

The Accademia degli Incogniti

Teatro Novissimo was promoted and funded by young libertine patricians who formed a literary salon called the Accademia degli Incogniti (Academy of the Unknowns), which during the 1630s and 1640s constituted the leading Venetian salon. Members included more than a hundred eminent poets, librettists, and historians all interested in influencing city politics and affecting social norms.Footnote 26 They also included foreigners as far-flung as Copenhagen and Greece and many from major Italian-speaking cities, forming a “cosmopolitan Italian network,” as Edward Muir refers to it.Footnote 27 Three other theatres—San Giovanni e Paolo, San Moisé, and San Cassiano—were owned by single noble families and produced operas in the city, but only Novissimo was built and operated by a consorted partnership of several patricians, including three Incogniti.

Despite proclaiming faithful adherence to the Venetian state, the group still tested accepted social and artistic parameters. Dissimulation, for the young libertines, was the necessary means by which one should resist restrictions to their freedoms without revealing personal dissatisfaction with the powers that be.Footnote 28 In the seventeenth-century, dissimulation was a tactic employed to obscure underlying meanings. Counter-Reformatory repression of individual expression necessitated such camouflage.Footnote 29 Therefore, it was the literary artist's duty to employ “active” dissimulation, perhaps publishing under a pseudonym, as an intervention against social strictures regardless of threats to life and liberty exemplified by Galileo's demise.Footnote 30 The Incogniti moreover advocated deception as a tool to subvert “all preconstituted authority,” as Lorenzo Bianconi asserts.Footnote 31 The published works of the Incogniti were well known to literati across Europe. Marco Arnaudo credits Venice's thriving commercial publishing market with facilitating the agenda to reform sociopolitical ideologies cloaked in linguistic devices like metaphor, omission, allusion, and emblematic images.Footnote 32

The Incogniti opposed strictures on sexuality and promoted the fulfillment of male desire in sexual pleasure as something intrinsic to male health.Footnote 33 Their thinking was influenced by scientific discoveries at the University of Padua revealing stark differences in male and female anatomy that contradicted the common belief that women's reproductive organs were simply inverted male genitalia.Footnote 34 For the Incogniti, newly discovered male and female biological distinctions, like the presence of fallopian tubes in women, justified gender discrimination but also underpinned challenges to accepted gender norms. Their push for male sexual freedom was straightforward, but their views on women were paradoxical. For instance, while they thought women inferior, they allowed them to attend their debates. They thought women innately corrupt and licentious, yet powerful in their sexual hold over men. Thus, as they distracted men from their patriotic duty to the Republic, women should be controlled and taught how to conduct themselves virtuously in chastity and silence. Conversely, they actively supported the careers of women singers in opera while championing both the novel operatic form and the Teatro Novissimo as the first theatre devoted solely to the production of opera. The new dramatic form was the perfect conduit for testing and broadcasting their brand of male sexual liberation. It was also a perfect genre for presenting a kind of musical drama that diverged from the aesthetic agenda set by the sixteenth-century humanist Florentine Camerata, whose members theorized on the function music had played in Greek drama. Regardless of what the ancients did, for the Incogniti music should appeal to popular tastes—whereby, as Muir purports, opera became Venice's “paramount contemporary art form.”Footnote 35

Members of the Incogniti contributed to and published Le glorie della signora Anna Renzi, and Renzi performed in several operas based on their libretti. The agitation of the Incogniti pushed the boundaries of gender performance in contradictory ways, and their celebration of Renzi proved intrinsic to her career. Clearly, if, as Fred Inglis declares, “Celebrity . . . is the product of culture and technology,”Footnote 36 then Venice's flourishing printing and publishing industry made Renzi's celebrity fame possible by advertising her performance, amid Torelli's technologically sophisticated stage wonders, to a European-wide readership. I also analyze the tributes to Renzi's performance genius and how, as a new kind of celebrity figure, she forged a new social status that helped usher in early celebrity culture, the intertextuality of which I work to elucidate.

As the first fully realized career operatic prima donna, Renzi demonstrated how operatic heroines were to be interpreted and performed. Such work garnered her, and the operatic form, a popular following and widespread renown. Renzi's body in live performance, moreover, was a social text that embodied and sounded forth something beyond the composer's written configuration of pitches, or the librettist's dramatic text, to loosen the grip of a textual narrative configured to reinforce essentialist views on women. Her voice, corporeal enactments, and the fame she won also endowed her with what Joseph Roach terms the “illusion of availability,”Footnote 37 especially in Novissimo's intimate performance space, built to host four to five hundred spectators.Footnote 38 (To theorize her social impact, the following section attends to the embodiment of celebrity status based in audience reception as reflected in contemporaneous accounts of Renzi performing in the opera La Deidamia in 1644.)

Indeed, Renzi performed a “radical textuality” and performative polyvalence, as Elin Diamond terms it,Footnote 39 inducing audiences to translate the epistemological text of her remarkable, radiant body. Her presence constituted a major force in the nascent arenas of commercial celebrity culture and operatic performance. Perhaps intended only to create a powerful aesthetic effect, I hypothesize furthermore that the diva's performative force, as a visceral affective force, “misfire[d]” to resist cultural restrictions on women's agency in Italian-speaking society as it reverberated politically in audience's thoughts.Footnote 40

La Deidamia

The opera that “M.T.” wrote about so fervently, in the poem at the opening of this article, was produced at Novissimo in 1645. Venetian publishers Leni e Vecellio printed a scenario for La Deidamia, sold before the production, while the libretto was sold on performance nights.Footnote 41 The opera was written and composed specially for Renzi by librettist Scipione Herrico (1592–1670). It contains seventeen characters, three of them mythological, is in three acts and twenty-nine scenes, and features prominently the plot device of disguise. The action occurs on Rhodes in its fifth-century bce republican period, with the opening scene depicting the Colossus of Rhodes (Fig. 1). The plot is typical of opera of the time. Prince Demetrius, who has sworn to marry Deidamia, is called away by his father to war and then betrothed to a woman named Antigona. Deidamia, determined to stop the marriage, fakes her own death, and disguises herself as a man named Ergindo so she can travel to retrieve Demetrius. Gender-bending in this opera takes primary focus and, for most of the opera, Renzi was costumed as a male hunter.

Figure 1. Giacomo Torelli (design), Marco Boschin (painter), “Il Porto di Rodi,” Deidamia, Prologue. Palazzo Malatestiano. Photo: Pinoteca Civica di Fano, Fano, Italy / Bridgeman Images.

Cross-gendered disguise in the opera leads to several homoerotic scenes. The female characters Eufrine and Astrilla, for example, are both infatuated with Ergindo, and in act I, scene 2 the two share a breathless exchange after encountering the beautiful “Ergindo” in which Eufrine asks, “So, you liked him?” Astrilla replies: “And how! / In his golden tresses, / Love pumps like honey. . . . / The two loving cheeks are a / Beautiful garden of lilies and roses.”Footnote 42 The homoerotic subtext is charged with double entendre as the audience hears one woman swooning over the other's “beautiful garden of lilies and roses.” Alternatively, in act II, scene 1, Demetrius remarks on the effect the beautiful “Ergindo” stirs in him, saying: “Here, see the mild appearance / Of Ergindo the boy, . . . / His gentle voice and his good looks” (50). In act II, scene 2, Eufrine happens upon the sleeping “Ergindo,” overhears him exclaim his love for Demetrius, and realizes that this is a “completely different” kind of love. Coming closer to him she declares: “Oh, what sweet ivory skin!” (55). But, as she touches it, she discovers “Ergindo's” breasts, questioning to herself, “How can this be, oh Heavens, oh Stars? / Do males have breasts? / . . . as far as one can see /. . . Ergindo is a young woman” (55) (Fig. 2). Later on, Astrilla finds “Ergindo” sleeping and cannot help but reveal her attraction to him, saying, “Wake up beautiful Ergindo, / Oh, how mild, and slim, / This gentle young man, / For whom there is no comparison in beauty” (58). At this, Ergindo awakens and condemns Astrilla's forwardness but, realizing her infatuation, tries not to blow his cover while fending her off. When Astrilla declares she wants “Ergindo” to love her and to “have if not the fruit, at least the flower” (59), he replies: “Of these flowers and fruits, / My field is sterile; / Devoid of the plant, / I cannot satisfy your desire” (59).

Figure 2. Giacomo Torelli (design), Marco Boschin (painter), “Cortile con Villa,” Deidamia, act I, scenes 1–3. Palazzo Malatestiano. Photo: © NPL–DeA Picture Library / Bridgeman Images.

Later, Deidamia, as Ergindo, insinuates to Demetrius that he shallowly fell in love with another woman just after the last one died. Demetrius retorts by claiming there was nothing he could do after Death took her. Eventually, as “Ergindo's” presence becomes too tempting, the conversation proves too disturbing, and Demetrius bids him to leave, saying, “Either talk about something else or depart. / Do not disturb my chest, / With the sweet flame of affection” (69). Deidamia presses him to explain himself until Demetrius insists: “But you graceful Ergindo, / Do not awaken new ghosts in my heart. / You are ill-suited to serve me, go elsewhere” (69). Deidamia, like the ghost in his heart, reminds him of their love and disturbs his commitment to Antigona. But her disguise as a boy most disturbingly makes him forget himself and makes his “cravings shine” (68). The conflicting themes of deception, homoerotic desire, temptation, self-control, and revelation lead the audience through turbulent emotional terrains, from identifying with Demetrius’ upsetting confusion to questioning Deidamia's unwise machinations. After seeming to want to kill Demetrius with a sword intended for herself, in act III Ergindo is put on trial for treason. However, Eufrine reveals Deidamia's true identity, Demetrius forgives her, declares his love, and all ends happily with the “rightful” return of sexual status to Demetrius as Deidamia's husband in marriage. Renzi's performance disguised as Ergindo demonstrated sturdy “male” courage in facing danger, vulnerability as a prisoner on trial, innocence in her belief in love, and experience in handling Eufrine and Astrilla's advances.

On the surface, the opera seems to reify the patriarchal order. The audience is instructed in the primacy and restoration of heterosexual marriage, while same-sex desire is contained, and the danger of dissembling women is brought under patriarchal control. Alternatively, same-sex desire and deception are seductively performed. Furthermore, when Deidamia, who uses sexual deception for personal interest, was embodied by the beautiful young Renzi, whose voice and performed sexuality were correspondingly overpowering, the conundrum for men in the audience was magnified. Renzi seemed to be the perfect vehicle to embody librettists’ messages on the dangers of female sexuality to men. Cross-dressed performance, both male-to-female and female-to-male, was considered erotic, was very popular in Venetian drama, and brought the public flocking to Novissimo. Rojek posits that subconscious and unconscious fantasies and desires surrounding the veracity of other people's true selves attracted early audiences, who were quite familiar with Machiavelli's widely published thoughts on dissimulation.Footnote 43

Disguise and cross-dressing in their “deception of the senses” was an integral dramatic device.Footnote 44 The gender reversals at carnival, where, as James Johnson maintains, “men in dresses act[ ] coyly, women in trousers act[ ] mannishly,” likely encouraged women to “rebuke priests,” confront “local administrators,” to chastise their husbands, and to step out of line in “more serious moments.”Footnote 45 The cognitive dissonance of witnessing, or even hearing about, highly paid and popular women singer-actors could embolden women in the city to rethink their everyday social status, perhaps even to dream of alternatives. However, Sandy Thorburn posits that there was enough surveillance by the Inquisitori di Stato (city police) over the opera industry to deduce it operated “simultaneously [as] part of the social fabric and the instrument that could tear it.”Footnote 46 This brings to mind Roach's assertion that transvestite performance routinely raised authority figures’ suspicions “on grounds of ontological subversion,” where the audience who “clamors for It” could also punish it.Footnote 47

Le glorie contains a confusion of terms involving nymphs, Sirens, swans, angels, hermaphrodites, and, most notably, monsters. The varying appellations indicate how Renzi's male receivers scrambled to reconcile her “natural femaleness” with her metamorphosis in staged embodiments, and its “monstrous” effect on them. Francesco Marie Gigante's tribute is titled “To the Monstrous Siren of Theatre.”Footnote 48 Another, anonymous author remarked that she had the power to “subjugate . . . the pride of those who already believed [her] valor to be equal” (44). In another, G.Z. effervesces, “ANNA in Ergindo . . . of whom no one else looks alike; / . . . Know . . . in truth, that you are a monster” (77). Another signed F.M. reads, “From Sirens arise, singing monsters,” whose “soft song makes rock stiff” (13). Her power to subjugate male pride forced an acknowledgment of female valor equal to their own. It was not only her characters, then, who tricked and manipulated the male characters; the real woman Renzi held real men in her thrall to efface their memories, stiffen rock, and cause them to “languish” out of control as she monstrously held power over them. It was something fearful but brought them streaming back for more. Throngs returned, as Incognito librettist Giulio Strozzi (1583–1652) attests, with “an unceasing desire to rediscover every evening this first of the Muse's sisters” even at the risk of being turned away from the door of a full theatre (6).

Strozzi published Le glorie della Signora Anna Renzi as a marketing strategy. As mentioned, M.T. exalts Renzi's luminous performance of Deidamia cross-dressed as Ergindo, in which she transgressed normative gender prescriptions while presenting a tantalizing diversion involving homoerotic scenes. The encomiast Gigante claims that “in full wonder, / And in amazement, those who hear lift their eyelashes,” but after committing this first mistake, “languishing in her force he is despondent” (88). Seeing her, he loses his male virility to languish, or “hang” as F.M.G. claims, limply in the pleasure of her potent resonance. Moreover, F.B. proclaims: “Your Music takes away Death / Strength, and reason” (58). Here, the penetrating force of the diva's sound caused one to forget everything else in its captivating appeal. Author F.B. asserts, “Beautiful Mermaid / Cause of my punishment . . . The auras fall in love with [your] sweet accents / And the winds are suspended in the air” so that “Love itself in love / hangs on your voice and ignites himself” (66). If she can cause Love to burst into flame, then imagine what she can cause mere mortal men to do. All this destructive potential was bound up in exceedingly erotic, sexual tension, and delivered through her voice.

About her performance as Ergindo, G.B. proclaims she is a “Rare monster of love / . . . in the guise of an earthly Angel” (70). This echoes Incogniti favorite Giambattista Marino's (1569–1625) poem where he wonders if a beautiful singer is more a “heavenly” or an “earthly Siren” whose “perfect beauty” encloses “an angel” rather than “a soul.”Footnote 49 The diva's sound and vision are otherworldly, but men's attraction to her is very much an earthly, sexual matter. The confusion lies in what is virtuous and heavenly versus what is lecherous and earthly, and the diva seems to manifest both simultaneously in ways that could not be ignored and that made her irresistible. The intelligent “‘manly’” powers of temperance should prevent men from falling into her trap.Footnote 50 In this, the virtuosa's attractiveness aligns her with the “predatory” prostitute.Footnote 51 M.T.'s description of Renzi as a magical “Hermaphrodite Beauty” reveals ambivalent attitudes toward displays of cross-gendered performance.

The diva presented a densely layered resonant system of sound, vision, and meaning for audiences to unpack to which they were compelled to attend but at whom men dared not look. This is because, if one did so, he was enraptured by the “Divine, charming face” and the “harmony in your voice,” as one writer attests.Footnote 52 Writer Filippo Picinelli (1604–ca. 1667) warns in his Mondo simbolico of 1658 that the listener must be doubly careful not to get caught up in “the force and effective energy of a beautiful female singer.”Footnote 53 The idea of the Siren able to entrap men with her singing and gaze, stems back at least to Homer's Odyssey. Elena Calogero discusses the fear that, like Homer's Sirens, the virtuosa could cause the “loss of rational [male] [self] control” and even “death.” Wendy Heller likewise quotes the founder of the Incogniti, Francesco Loredano (1607–61), who wrote that when a beautiful woman gazes on her lover it is like “poison darting from” her eyes that “takes away the lover's life,” blackening his face, suggesting that black depicted the destruction of his soul.Footnote 54 Reactions like those contained in Le glorie are nowhere more apparent than in the writings of the Incogniti.

The sexual agenda that the Incogniti promoted was reflected in their publication of homo- and heterosexual erotica in books forbidden by the Catholic Church. Here, they claimed they were exercising “Republican freedoms.”Footnote 55 As the foremost Venetian literary salon, their disregard for social norms was important. In Incognito member Ferrante Pallavicino's (1615–44) 1641 novella The Post-boy Robbed of His Bag, he claims that the only rational capacity women possess is will, but that it is “so submerged by the passions that . . . woman is without judgment. Whether her lust is boundless or her rages out of control, she knows no moderation,” and is therefore not human.Footnote 56 In his The Whores’ Rhetoric of 1642, a terribly poor girl comes to an old woman's home begging for help. The woman teaches her how to be a courtesan and, in the end, a client rapes the girl anally and disfigures the old woman.Footnote 57 Here, Pallavicino claims that prostitutes are “like shitholes and urinals exposed to the common benefit of whomever wants to discharge excessive semen.”Footnote 58 According to Paolo Fasoli, what mattered to Pallavicino's readers most was learning about “the tricks, mechanisms, and deceptions of whorish rhetoric.”Footnote 59 In Giuseppi Passi's (1569–1620) marriage manual of 1599, he claimed that women possess traits of pride, lust, envy, ambition, avarice, and especially a “desire for power” but that their most egregious fault was deceptiveness, counseling young men to learn about women's “deceits” in his book.Footnote 60

A major preoccupation of Incognito debate and publication concerned women's sexual power that was linked, as Heller attests, to the irresistible pull of music, both of which could lead men to abandon “masculine” self-control. Loredano warns readers about women's potent sexuality, their penchant for deception, and the intractable hold that they wield over men writing, “If she speaks, she lies, if she laughs, she deceives, and if she weeps, she betrays. . . . With her eyes she enchants, with her arms enchains, with kisses stupefies, and with the other delights robs the intellect and reason, and changes men into beasts.”Footnote 61 In the experiment of Venetian opera, the theme of women's sexual prowess is repeatedly pitted against men's obligation to dominate and subjugate them—even to the point of rape—to male sexual will.Footnote 62 In her deceptive disguise, the character Deidamia, especially embodied by the mesmerizing Renzi, actualized some of the fears about which Loredano raves. In the final opera produced at Novissimo with a libretto by Bisaccioni and music by Giovanni Rovetta (1595/97–1668), Ercole in Lidia of 1645, Renzi played the male role of Alceo, who cross-dresses as a lady-in-waiting named “Rodopea.” Alceo cross-dresses in order to be near his love interest, Onfale. At one point, Onfale reciprocates “Rodopea's” love before she learns that Alceo is a man. Carlo Bosi, following Rosand, again ties such homoerotic subject matter to the Incognito fascination with gender play as dissimulation.Footnote 63

In the aftermath of the performance, Renzi departed Novissimo into the nocturnal city where the sovereignty of celebrity played out in the autonomy of her public persona. To place Renzi's activities into the broader gendered social configuration, I offer some salient information on the status of women in Venice. Upper-class women were particularly restricted from going out into publicly designated “male” spaces, especially in the early seventeenth century. This is, as Anne Jacobson Schutte imparts, fears about protecting women's chastity caused, “political authorities and patriarchs” to restrict all women's movements to “their homes and one or two adjacent contrade” or parishes.Footnote 64 When they did venture out in public, the elite women, who were under even stricter constraints on their movements in the city, teetered about on platform shoes called chopine or pianelle and had to be supported by their servants to stay upright.Footnote 65 After midcentury, women of the patrician class attended salotti (or salons) and ridotti (gambling halls), along with plays and operas.Footnote 66 No matter where they went in public, they had to be accompanied by a man of their own class, known as a cisisbeo. Footnote 67

Nonelite or working-class women had more freedom of movement in the city to and from notaries’ offices, places of business, charitable institutions, homes of friends and family, and their places of employment.Footnote 68 While women's dowries in all class levels financed much of the family expenditures and investments, women were delegated to the sidelines when it came to the management of businesses, as men were meant to conduct business in the public realm.Footnote 69 Women workers, according to James E. Shaw, were cheaper to employ and, as they were not allowed guild membership, and so lacked protection, they were “easily exploited by male-controlled merchant capital.”Footnote 70 Male heads of households, as Schutte explains, held the responsibility and the right to “govern” their servants, children, and wives, often “with an iron fist.”Footnote 71 Neither elite nor working-class, the independent Renzi traveled to Venice to launch and sustain much of her career as a professional performer.

Ostensibly, whether Renzi intended to liberate women from oppression, the force of her sounding image held the promise of it. Even if the promise of independence and freedom to attain personal potential and self-fulfillment remained elusive for most Venetian women confined to the domestic sphere, sexual servitude, or to a convent, the diva's very existence onstage and in the city countered patriarchal authority. This is not to say that professional women performers were free from detractors and accusers, however.

Performing Virtuosity Virtuously

In Le glorie, Strozzi noted Renzi's method of studying and then replicating human behaviors onstage, explaining that she silently observed peoples’ behaviors and applied the “spirit and valor” learned from those observations in performance.Footnote 72 Strozzi praised her intelligent expertise, writing that Renzi possessed “the sublime genius one seeks, that is, great intellect, much imagination, and beautiful memory, as if these three things were not contrary, and yet in this same person no natural contradiction exists. All the gifts of a courteous nature that knows how to unite these three attributes.”Footnote 73 Strozzi described Renzi's vocal technique, the eloquence of her delivery, and her “tour de force” stamina singing night after night. The following description is unusual in its detail and reflects Strozzi's status as a practitioner well versed in the accepted performance practice of the time:

She masters the scene, intends what she utters, and utters it clearly . . . with a suave pronunciation, not affected, [without] . . . full voice, but sings sonorously, not harsh, not hoarse, nor offending you with overwhelming subtlety. . . . [S]he has a happy passaggio, a daring double and reinforcing trill, and all is interwoven with her, who twenty-six times, carried all the weight of the opera that was replicated almost every evening one after the other.Footnote 74

On her elocutionary style, Renzi seems to have conformed to performance practices described by an anonymous author of the manuscript treatise Il corago [The artistic director] (ca. 1630). In it, the author advises aspiring dramma per musica practitioners that though elocution is the basis for good acting, a good actor should also be a good musician:

Above all, to be a good reciting singer, one should also be a good reciting speaker, because we have seen that someone who has particular grace in acting can do wonders when they also know how to sing. About this, some question arises whether to select a bad musician who is a perfect narrator, or an excellent musician with little or no acting talent. Some very few music connoisseurs prefer excellent singers who are cold in recitation, while common theatregoers get greater satisfaction from actors with perfect instincts but who have mediocre voices and musical expertise.Footnote 75

Renzi's acting was well received, and she was likely aware of the priorities expressed in Il corago. This is in part because she sang in recitative form meant to carry dramatic action but not in still moments of single “affects” that the aria soon came to signify. Her superb singing made her the perfect vehicle to introduce operatic virtuosity, beyond what audiences had experienced before, to a public who expected great acting—and she delivered both.

Renzi's acting abilities in turn helped to establish the operatic form as a valid dramatic form in Venice's thriving theatrical life. In Le glorie, Strozzi wrote, “Our Lady Anna comes alive with expression, it seems like her speeches are not learned from memory but are born in the moment. In sum she changes to become the person she represents.”Footnote 76 Her ability to transform herself seamlessly in performance is known in Italian as sprezzatura. Baldassare Castiglione (1478–1529), as Natalie Crohn Schmitt submits, defined sprezzatura as a kind of dissimulation, as “an art to . . . make whatever is done or said appear to be without effort” so it becomes art “which does not seem to be art.”Footnote 77 Renzi mastered performative dissimulation onstage with sprezzatura.

Strozzi's laudatory volume is one way that Renzi's fame spread beyond Venice. I contend moreover that it was a device that helped to construct, consolidate, and define the newly forming social persona of the independent professional woman performer. Without Renzi's ability to personify convincingly the everyday role of a constrained and virtuous woman this might not have been possible. Strozzi praised Renzi for her calm and steady nature and her “melancholy temperament,” stating that she was a woman of few words but when she spoke, it was with “shrewd, sensible, and worthy” words and “beautiful sayings,” praising her for her reserved and chaste personal and private behavior.Footnote 78 She performed virtuosity onstage and virtuousness in her everyday performance of self. This matters because, while forging the new social role, she faced a prevailing attitude, expressed by the Jesuit Giovan Domenico Ottonelli (1581–1670), contending that women performing in public endangered not only their own morality but, most egregiously, also that of the men in the audience.Footnote 79 By broadcasting Renzi's reserved personal deportment in everyday life, Strozzi's approbation diluted the threat of Deidamia's fictitious power over Demetrius, as it did the moral threat of Renzi's public performance to men. Indeed, with male authority, Strozzi legitimated her position as a consummate professional by publicizing her reputation as a virtuous woman in everyday life, thereby lending her protection from public censure. Her public persona camouflaged a radical threat to patriarchal control exemplified by her ability to conduct her career autonomously.

Renzi's performance of virtuosic verbal, physical, and sonic feats in cross-dressed roles called a new social subject into being. Her performance of gender in everyday life helped to reformulate how women could live by revealing a new type of womanhood. Her celebrity status wrought her an influential position as a new role model for women even within the newly regularizing practices of operatic performance conceived of and authorized by male figures. Male authority allowed her performance in venues where she enacted regulated practices of the habitus just as her embodiments resisted the norm. In these ways, she helped to reconfigure gender norms through the masterful dissimulation of gestural codes with which the public concurred. Such public approval countered accepted tenets propounded by misogynist pronouncements on women's limitations, resulting in entrenched and hegemonic social doctrines that kept women in subservient positions. With her commanding public presence, display of artistic acumen, and personal autonomy the diva materialized an alternative to the misogynist lie about women's inferiority.

While audiences arrived already informed by ideological social norms in what Pierre Bourdieu calls the “social field,”Footnote 80 they departed the theatre changed to transmit their experience of the diva back into the city. The librettists’ female characters, cross-dressed and acting with masculine autonomy, were subjugated to male control. This was a powerful tool for educating audiences on how to contain women's agency. Even though court operas had been performed for exclusive aristocratic audiences (mostly by all-male casts) for many years before the first public opera, there was a wild unpredictability about performances in the commercial theatres for a popular audience. Hence, the energetic dynamism of Renzi's soniferous body formed a nodal point—an ideal liminal space—of transgressive gender performance before a paying plurality consisting of tourists, diplomats, aristocrats, and Venetian citizenry. Such diverse assemblies ensured that word spread about Renzi and Venetian opera across broad social networks and political borders.

Achieving Celebrity

I turn now to Renzi's actualization of commodified celebrity. Word of her celebrity status spilled out into the world with the throngs of journeying tourists and tradespeople, as well as through diplomatic missives, published documents, iconography, and letters. The explosive impetus of the Incogniti advertising blitz conveyed to the Western world the impression of the Novissimo theatrical space and the unique performance dynamic it housed. Together, the entrepreneurial marketing strategy, the new operatic venue, and its great independent performers generated unbeatable celebrity force.

One surviving image of Renzi, used to advertise her performance in Novissimo, contains this sentence: “Intimacy if sung soothes the heart” (Fig. 3). Elizabeth Belgrano highlights androgynous attributes in the portrait, including Renzi donning a “male” military vest and paned sleeves beneath a doublet, and although her curly hair falls about her shoulders, it is in a short, fringe style fashionable for men in that time.Footnote 81 She also wears “female” earrings, hairpins, a brooch, and a necklace, all of which, argues Belgrano, epitomize her protean ability to transform from male to female characters in performance.Footnote 82 Belgrano's description of the androgynous rendering epitomizes Roach's idea of the “role-icon.”Footnote 83 The portrait also invokes differing perspectives on its subject. There is the performer known as Anna Renzi. There is the private person about whom little is known. Then there is the public persona of the professional virtuosa out in the city.

Figure 3. Jacobus Pecinus Venetus, Romana Anna Renzi. From the house program for La Didone, Teatro la Fenice, Venice, 13 September 2006.

Roach quotes romance novelist Elinor Glyn (1864–1943): “To have ‘It,’ the fortunate possessor must have that strange magnetism which attracts both sexes” (4). While there is no concrete evidence of Renzi attracting women sexually, the possibility is undoubtedly high, as women constituted a portion of her audiences. Nevertheless, early audiences became aware of her movements and performances through documents that recorded and advertised them, causing patrons to look forward to experiencing her as a role-icon. Roach insists that with broadly distributed print publicity, expectations were raised in anticipation of such exceptional interpreters and their “auratic presence” at the performance event, increasing box-office intake (40). Her portrait, moreover, helped Renzi to achieve the “It-Effect”: her image circulated as a portable yet “unobtainable” celebrity that indelibly engraved itself into the desiring consumer's mind (76).

Roach defines role-icons as being “abnormally interesting personae” whose images spread with mass publishing and publicity to transform general “preconceptions” about them into “more specialized” or “standardized . . . role-icons,” like “‘femme fatale,’ ‘rake,’ ‘fop’ and ‘pirate,’” made so through “novel iterations by exceptional interpreters” (12). On transvestite performance, he purports that when the charismatic performer assumes the typical gender markers of the opposite sex, “the uncanny allure of It intensifies,” assuring transvestism a prominent place in great theatrical traditions (11). In baroque operatic roles, female characters usually cross-dress as men in order to move freely through male spaces. Fictional depictions, or any woman cross-dressed (en travesti) involved the transgression of women into the male power scheme. Whether she dressed in designated male attire or just embodied “maleness” by virtue of her eloquence in virtuosic rhetorical skill, she was thought by male commentators to “become” male. The effect is amplified when the performer is a consummate performer. Within Novissimo's intimate auditorium, Renzi in performance, I argue, cast a doubly potent spell as she embodied the “epitome of a type or prototype” of influential, even emulatable, celebrity that witnesses recognized (6).

Difference is perceived and awareness of difference permeates the social network as part of the “socio-temporal dynamics” of the public sphere.Footnote 84 This reality is more obvious in a lagoon city like Venice, with its watery boundaries and restricted space channeling peoples’ movements through narrow passageways, and canals placing pedestrians and those in boats into close contact. Proximity increases the likelihood that individuals encounter each other along the way whether they interact personally or not.Footnote 85 Venice's private residences, with their balconies, doorways, and windows open to public view, likewise afforded residents’ scrutiny of the walkways, canals, and public spaces, including interconnected piazzas clustered together and filled with people.Footnote 86 Indeed, people of varying socioeconomic classes lived together in the same neighborhoods, where men and women of all classes by necessity passed one another in public spaces.Footnote 87 Within the tightly packed architectural complex,Footnote 88 citizens were undoubtedly aware of the diva's unique status.

The connectivity of performer and audience is bidirectional. On this, Sharon Marcus contends that “celebrities ranged between exemplarity and impudence.”Footnote 89 When the diva performed virtuosic feats, she was an exemplar, but when she performed en travesti onstage, and independence in everyday life, she was impudent. In the aftermath of performance, the exemplary performer's somatic presence reverberated indelibly in people's minds, generating celebrity power as the iconography served as indexical representation to the world. If, as Rosand contends, Renzi was partly “created” by the print publicity successfully generated by the Incogniti, what else “created” her?Footnote 90 Renzi wisely separated her private and public lives by maintaining a reserved offstage demeanor that protected her reputation and kept her admirers guessing as to her private thoughts.

Renzi's professionalism, self-possession, and perspicuity marked her out as a role-icon matching Glyn's definition, whereby “To have ‘It’ . . . [h]e or she must be entirely unselfconscious and full of self-confidence, indifferent to the effect he or she is producing, and uninfluenced by others.”Footnote 91 The early operatic diva confronted her audience with her difference as a powerful singer, able to realize and embody believably what were thought strictly “male” characteristics, and her abilities to defy regulated gender norms. Such transgression is impudent, but fascinating. Her celebrity status lent her performance a multilayered citationality, presenting a great deal to contemplate. While she embodied the historians’ and librettists’ character constructions, she also effectuated a personal interpretation of the character. Audiences beheld a stunning presence able to execute virtuosic intelligence. In the flux and flow of becoming, Merleau-Ponty emphasizes, “the presence of the world is precisely the presence of its flesh to my flesh,” and the diva's presence infiltrated her audiences’ flesh to arouse amazement and desire, and to move emotions while influencing thought.Footnote 92 The diva's extratextual energy force generated a sonorous afterimage that reverberated out through audiences into society.

On an economic and political level, I argue that performances in Novissimo exemplified a new mixture of Old World patronage and the commercial economy. For Rojek, celebrity culture constitutes a redistribution of social power, where celebrities who come from the “mass and form of the people” create “staged celebrity” as opposed to royally “ascribed celebrity.”Footnote 93 Furthermore, “[s]taged celebrity refers to the calculated technologies and strategies of performance and self projection designed to achieve a status of monumentality in public culture.”Footnote 94 With technologies like Torelli's magnificent machines, the commercial publishing industry, and the phenomenon of virtuosic performance, “achieved celebrity” acquires “enduring iconic significance.”Footnote 95 Within this formidable mix Renzi, a woman of middling social status who came from “the people,” achieved iconic and enduring significance.

In the following, John Evelyn, in his published travel diary, offers a slice-of-life description of an encounter with Renzi:

The diversions which chiefly took was three noble operas, where were excellent voices and music, the most celebrated of which was the famous Anna Rencia, whom we invited to a fish-dinner after four days in Lent, when they had given over at the theatre. Accompanied with a eunuch whom she brought with her, she entertained us with rare music, both of them singing to a harpsichord. It growing late, a gentleman of Venice came for her, to show her the galleys, now ready to sail for Candia. This entertainment produced a second, given us by the English consul of the merchants, inviting us to his house. . . . This diversion held us so late at night, that, conveying a gentlewoman who had supped with us to her gondola at the usual place of landing, we were shot at by two carbines from anther gondola, in which were a noble Venetian and his courtezan [sic] unwilling to be disturbed, which made us run in and fetch other weapons, not knowing what the matter was, till we were informed of the danger we might incur by pursuing it farther.Footnote 96

This intriguing excerpt describes Renzi's celebrity status but also offers a glimpse into the Venetian nightlife at carnival and the unruly dangers at play. Renzi was out this night performing at a private gathering, went off then to see the galleys with a Venetian “gentleman” to whom she was presumably not married, and later met with a foreign ambassador. This is a level of free movement to which most “honest” Venetian women, confined to their houses and cloistered rooms, had no access. If courtesans and prostitutes enjoyed such a privilege, Renzi was not known to be either; so what social status allowed her this freedom of movement? I postulate that, even as she was accompanied by men, she also forged a new and different status from women who sold their bodies for sex. She achieved a status somewhere between an aristocratic woman, who might also have been out with her husband or other appropriate man, and that of a courtesan. Here, Renzi performed a kind of in-betweenness while pioneering a new celebrity status for women artists. Because her social background was not privileged, the status she won enabled her to exercise, and publicly demonstrate, personal autonomy in new ways for women. This achieved celebrity worked to democratize the diva's social status in the commercial marketplace and other public spaces.

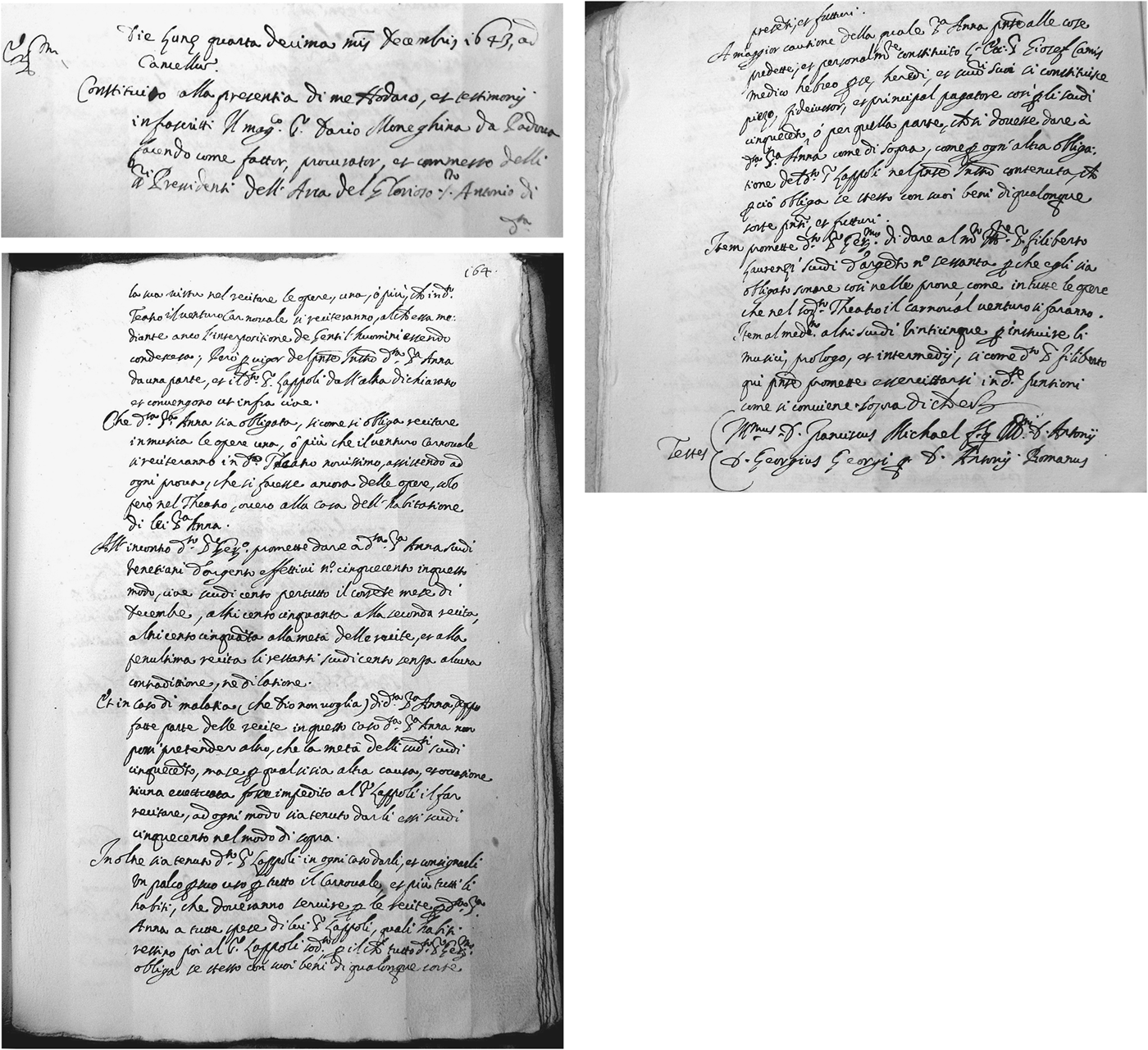

Sound and Vision Travel On

Renzi's financial independence further challenged societal norms. Added to Renzi's onstage virtuosity was her transaction of business, as a “mercenary” artist, in daily life.Footnote 97 She was not only an object for commodification; she also negotiated her own singing contracts. In her contract of 1643 (Fig. 4) for Novissimo, she is referred to as “S[ignor]a Anna,” and the physician Giosef Camis is listed as guarantor for her salary. On 17 June 1645, Renzi's supporter, nobleman Alvise Michiel, created a wedding contract registered with a notary for Renzi and Roberto Sabbatini.Footnote 98 The document contains several remarkable elements. It stipulates that Roberto will “promise now for the time being to marry her” and that Renzi would give everything she owned in Venice and Rome to Roberto, including the earnings gained from her Venetian performances, but all would be invested into a “dowry fund” (515–16). Roberto was “obliged to support his wife, her mother, [and] servants . . .” (516). As Beth Glixon points out, there is no evidence that a wedding ceremony ever took place, nor is there subsequent mention of Renzi being married (516). Perhaps she used this document to fake a marital status that would legitimize her as a so-called honest wife and present herself as above reproach to thwart public criticism and enable her also to travel unmolested. On this Glixon states that the document “patently reflects the life of a working professional woman” (516).

Figure 4. (facing and above) Anna Renzi contract of 1643. Busta 658; Beaziano (aka Beatian), Francesco, 1643 II; Archivio di Stato Venetia, Venice. Author's reproduction.

Renzi's contract with businessman and impresario Girolamo Lappoli employed her to sing the title role in La Deidamia and stipulated that, in case of illness, Lappoli would be obliged to pay only half of her normal pay. He would be “obliged to give and consign to her an opera box . . . for the entire Carnival and in addition, all the costumes she will need for her performances,” which would, however, remain Lappoli's property (513). In all these transactions, Renzi relied on men of the professional class to legitimize her business dealings. In July 1645, Renzi and several other singers sued Lappoli for unpaid wages.Footnote 99 Luckily, as Renzi utilized notaries to conduct her business affairs, a fair amount of evidence remains regarding her activities and movements to and from cities like Innsbruck, Rome, Florence, and Venice.

From 1645 until 1648, heightened activity in the Fifth Ottoman–Venetian war saw the closing of theatres and a halt to carnival entertainments in Venice. The closure prompted troupes of newly unemployed singers and other theatre practitioners to band together and search elsewhere for performance venues. By virtue of this precarity, the form was carried throughout northern Italy and beyond, and La finta pazza was one of the very first to travel out as part of the new itinerant operatic cycle with the Febiarmonici singing troupe, as Lorenzo Bianconi informs us.Footnote 100 By 1650 choreographer Giovan Battista Balbi's (1616–57) troupe performed in Florence with La Deidamia starring Renzi as prima donna and coproducer. Her contract “stipulated that Renzi was required to go to Florence at her own expense to perform an opera of Balbi's choice.”Footnote 101

While the commercial operatic form was in this nascent phase, troupes like the Febiarmonici and the Discordati participated in the process of displacing the older commedia dell'arte form. On this transitional stage, Nicola Michelassi points to Pirrotta's assertion that, as audiences were used to the improvisational modules of commedia dell'arte performance, operatic troupes adjusted their performance structure to accommodate their expectations.Footnote 102 Performers were expected to add prepared improvisational moments to their performances. Acting abilities, then, should equal musical skill. In addition, as a consequence of close proximity—with similar traveling routes, cities, and performance spaces and similarities in performance and rehearsal processes—commedia dell'arte and operatic troupes were essentially “of the same society,” conceiving of and implementing their performances in the same ways.Footnote 103 Michelassi also believes that it was with the touring of La finta pazza to Florence and the changes to the music and libretto for it that “the osmotic contact” between “mercenary” operatic troupes and “ordinary” commedia dell'arte troupes began.Footnote 104 Renzi played an integral part in these freelance collectives spreading the new cultural and economic paradigm in commercial exchange. By October 1652, Renzi was back in Venice, where she had the notary Francesco Beatian (aka Beaziano) draft her will.Footnote 105 There is no mention of children or a husband in that will.Footnote 106

In 1653, Ferdinand Charles, Archduke of Austria, requested that composer Antonio Cesti (1623–69) bring Renzi to sing for his court in Innsbruck. There, in 1654, Renzi sang the title role in Cesti's La Cleopatra at Innsbruck. At Innsbruck, she also sang in Cesti's opera L'Argia (1655) and performed for the cross-dressing Queen Christina, who was on her way to Rome after abdicating her throne.Footnote 107 She did not, however, remain at Innsbruck to become a court musician but returned to Venice to sing in its commercial theatres.

An exceptional element of her story is that, whereas earlier court singers like singer-composer Adriana Basile (ca. 1580–ca. 1640) had aristocratic patrons connected to specific courts, Renzi worked freelance. Commedia dell'arte diva Isabella Andreini's (1562–1604) international performances and widely circulated iconography, traveling with her family in the Gelosi troupe, worked powerfully on a social level, as she was one of the first professional women performers depicted in this way. In professionalizing the female performer in public theatres, commedia dell'arte women were forerunners to the operatic divas. Again, although Renzi may have utilized noble patrons or protectors along the way, she moved independently of any court or traveling troupe. Therefore, if Roach is right that “enacting the public intimacy of one role-icon, ‘the professional woman,’ . . . in some respects descends genealogically from another, ‘the actress,’”Footnote 108 then these performers, who very intimately affected their audiences, personified social change in a powerful way. Renzi inherited this unique position, and her personal status as an independent artist also expanded it.

The Monstrous Hermaphrodite

The language in Le glorie's encomium poems exalt Renzi's powerful singing and presence but also call her a “monster,” like the boy Ergindo, able to lure men into irrational thoughts and behaviors. On the contemporaneous use of the term mostruoso or monstrous, Matteo Fadini presents the case of a “monstrous birth” consisting of a stillborn fetus with two heads found in Trent in 1620.Footnote 109 Beyond that example, Stella Carella discusses the writing of seventeenth-century Dominican philosopher Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639), whose Del senso delle cose e della magia naturale was published in 1620. In the work, Campanella presents his theory on “monsters,” based in the writings of Galen and Bernardino Telesio, positing that the fetal environment causes malformations like hermaphroditism. “Hermaphroditic morphology,” claimed Campanella, is caused by a deformed uterus and the preponderance of semen in the genital area of the fetus.Footnote 110 Other factors like astrological influences—and even the effect of the mother's imagination if, for instance, she sees a monster—can also contribute to the malformation of the fetus, a woman being organically inferior and “weak bodied.”Footnote 111 Campanella groups “human monsters” with “hybrids” like half-human “half-beasts,” suggesting that adult women may actually become men but that men could become women only in fantasy.Footnote 112

In this period, it was assumed that when a woman cross-dressed, she embodied the baffling but fascinating figure of the hermaphrodite. Ruth Gilbert discusses how during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the figure of the hermaphrodite excited great interest and was the subject of much publication. She differentiates between the Platonic ideal of the perfect completion of male and female into one being and the Ovidian notion of the hermaphrodite as a “grotesque fusion” corresponding with Campanella's conceptions on monstrous hybridity.Footnote 113 Gilbert suggests that, in the paradigmatic economic and cultural shifts of the period and the unstable cultural transformation it wrought, the hermaphrodite figure was used to reconcile transitioning constructs of gender.Footnote 114 In The Anatomie of Abuses of 1583, for instance, the British Puritan Philip Stubbes (ca. 1555–ca. 1610) claimed that cross-dressing women were properly called hermaphrodites because they are half men and half women, and so were “monsters of both kindes.”Footnote 115 For Stubbes it was not that transvestite women were biological hermaphrodites, but more that they “enacted . . . hermaphroditism” as a cultural construct.Footnote 116

In the Greek myth of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis (Fig. 5) an adolescent boy wandering through the forest of Caria comes upon the nymph Salmacis at a pool. Salmacis automatically desires him, but he rejects her advances. When she leaves, the boy undresses and starts to bathe, but she returns and wraps herself around him, praying to the gods to keep them forever entwined (Fig. 6). Her wish is granted, so the two became one being of two sexes (Fig. 7). In Giovanni Boccaccio's (1313–75) rendition of the story, Salmacis’ seductive language is characterized as “thoughtless or lascivious” and so “‘female,’” as opposed to “‘manly’” male speech anchored in “the principles of logic” and thus “factual, appropriate, sober, well structured.”Footnote 117 But the female Salmacis, whose approach to seducing Hermaphroditus is inappropriately “aggressive,” indulges in vice and sin, and is morally corrupt like a prostitute or the allegorical Lascivia.Footnote 118 The allegorical figure (Fig. 8) is personified in the 1627 painting by Paulus Moreelse (1571–1638). In it, a woman is shown with one exposed breast, indicating that she is a prostitute or courtesan who represents Lascivia. She points to her own reflection, suggesting female vanity, as her direct gaze tells us she is shamelessly open to our advances. Before her lie gold chains and jewelry, suggesting female luxury. Behind her hangs a painting of Salmacis attempting to rape Hermaphroditus, representing a reversal of assumed male prerogative. A small book on the table reveals the following text: “Lascivia does not live for herself, but for Venus only. / To her she dedicates gold and jewels and all riches,” alluding to sexual favors as commerce.Footnote 119 Ultimately, the “strong” cross-dressed diva and the “weak” male audience member who fell prey to her powerful, lascivious charms, doubly threatened the equilibrium of the patriarchal order.

Figure 5. The Nymph Salmacis and the Hermaphrodite, Francesco Albani (1578–1660). Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany / Bridgeman Images.

Figure 6. George Sandys, Ovid's “Metamorphosis” Englished, Mythologiz'd, and Represented in Figures (Oxford: John Lichfield, 1632), Book IV; detail showing the merger of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (left).

Figure 7. Vecchio Satiro ed Ermafrodito, Pompeii, National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8. A Girl with a Mirror (Lascivia), Paulus Moreelse (1571–1638), signed and dated 1627. Oil on canvas, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Photo: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

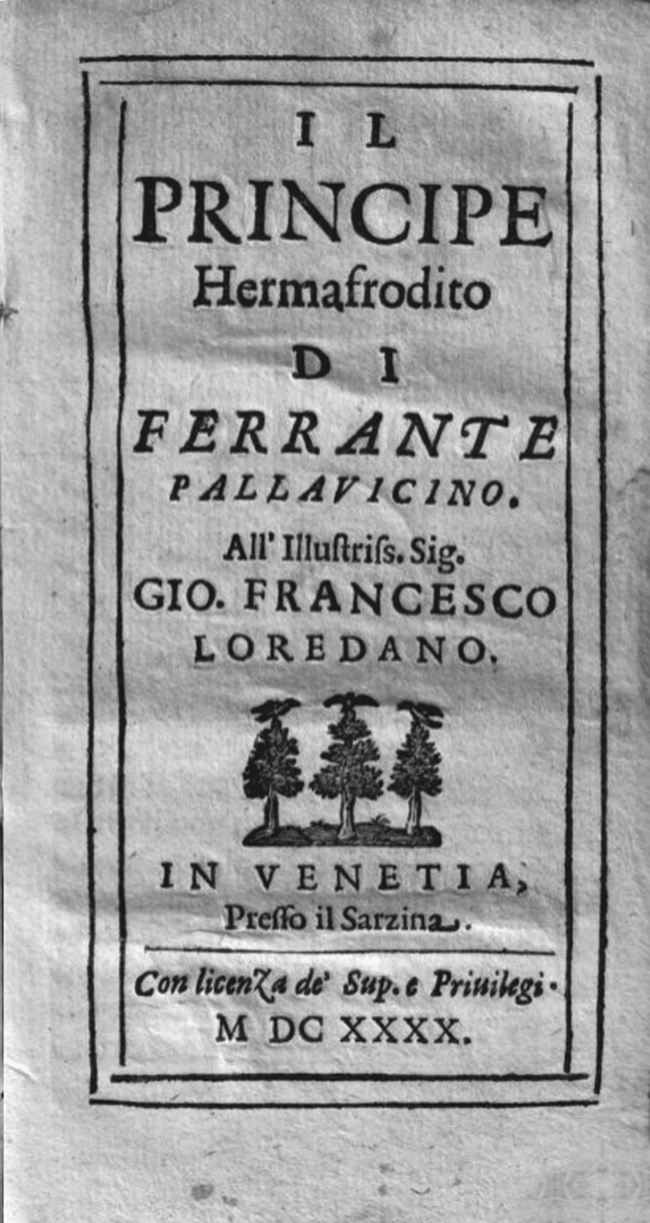

Contradictory attitudes regarding women are demonstrated in Pallavicino's 1640 novella The Hermaphrodite Prince (Fig. 9). In it, because Salic law has prohibited women from inheriting, and to keep the kingdom in the family, a Sicilian king raises his daughter as Prince Hermaphroditus. Hermaphroditus has no idea that he is a girl until a portrait of him is painted. On viewing it, he sees the likeness of a “Goddess” and questions the artist about this false depiction. The artist retorts, “I condemn the temerity of him, daring to contradict the . . . apparent signs of a virile body.”Footnote 120 When the king arrives, he worries that the prince has discovered his deception, where “the limping of lies easily turns into a fall” (10). The king then declares to Hermaphroditus, “Who does not know how to lie, does not know how to reign. . . . So in you my daughter I also made sex lie, to enable you to inherit this Kingdom,” adding, “you alone can cause its abortion”—though if she does so, she will lose the kingdom (10–11). There are several instances of cross-dressing, both male to female and visa versa, along with hetero- and homoeroticism in the story. At one point, Prince Alonso, cross-dressed as a woman, finds himself attracted to Hermaphroditus. When she understands this she tells him she has a twin sister, and that they share “the uniform similarity of two bodies, distinct only in sex” (36). Cross-dressed Alonso finds himself equally attracted to the sister, who is Prince Hermaphroditus cross-dressed, who tells him that, although a man alone carries “the scepter, to which every woman obeys” (49), they cannot be “knotted with a close union of affection” with “bodies whose surface is equally flat” (50). Here, Pallavicino, as narrator, asserts that although same-sex desire is a “disorder not accepted in nature,” Hermaphroditus was nevertheless a true hermaphrodite able to simulate appearances of both a man and of a woman (96). In the end, Alfonso and Hermaphroditus divulge to each other, and to the court, the reality of their biological sexes. Hermaphroditus abolishes the law against women inheriting, and they marry so that the family fortune is retained. Hetero normalcy is thus restored, though the hermaphroditic performance contains the promise to change patriarchal law.

Figure 9. Title page of the first edition of Ferrante Pallavicino, Il principe Hermafrodito (Venice: Sarzina, 1640).

In the experimental novella form, Pallavicino followed the libertine literary strategy of radically criticizing existing ethical and political ideologies by refuting tradition and accepted morality. The Inquisition's actions against Galileo, and their beheading of Pallavicino at age 28, were concrete examples of why subversive ideas had to be concealed by dissimulation. Roberta Colombi suggests moreover that the masking and disguise in The Hermaphrodite Prince reflects the impetus to resist the oppressive social order as necessary to civil life, just as the order itself caused subjects to deceive through dissimulation.Footnote 121 The gender play, sexuality, and transvestism in The Hermaphrodite Prince, Ercole in Lidia, and La Deidamia, reflect the new thinking on sexual difference at the University of Padua that brought “natural” laws on gender and sexuality into question.Footnote 122 By extension, the naturalness of the Venetian noble family structure, where only one son per generation and only daughters with large enough dowries could marry (resulting in an abundance of patrician bachelors, courtesans, and nuns in the city), was also questioned.Footnote 123

In assuming masculine gender traits, Gilbert remarks that cross-dressed women became “monstrous hybrids,” whose deviance distorted their “‘womanly’” essence.”Footnote 124 This led to the concept that gender could easily be performed and transferred between the sexes regardless of genitalia.Footnote 125 If a woman regularly cross-dressed in public, to gain access to spaces normally prohibited to them, it was thought false and deceptive behavior that threatened the moral and political fabric of the community. To reconcile such disorder, and rectify the “natural” hegemonic order, Venetian librettists subjected female heroines to patriarchal norms and priorities by rendering their “unnatural” personal and political gains to male characters. By dressing in designated male attire, either onstage or off, a woman crossed into the male sphere to access male power. In dressing as a man, she became a man to enjoy the privilege of free movement as other men did. Onstage, Renzi could dress and act as a fictional male, and in everyday life, as an independent individual conducting business in the public realm, she exercised freedoms normally reserved to male privilege.

Conclusion

The diva tested the limits of rules and laws governing women's freedom of movement and decision in Venetian society. However briefly, Renzi occupied a powerful social position. Her own merits as a great singer-actor were embellished and broadcast by the Incognito marketing strategy. Her image as a star was, as Rojek puts it, “inflected and modified by the mass-media and the productive assimilation of the audience” so that “a dispersed view of power [was] articulated in which celebrity [was] examined as a developing field of intertextual representation in which meaning [was] variously assembled.”Footnote 126 It was left to audience members to decipher and interpret the various meanings presented to them in Renzi's performance. Performances transmit a sense of identity, social knowledge, and memory where embodied practices are part of broader cultural discourses sometimes offering new ways to be. As part of the cultural discourse, Renzi's performance of difference offered new and alternative ways of being to contemplate.

As the diva took command of the stage, her body, sound, and the presence of her intelligent sprezzatura exceeded the speech act it performed in a way inconceivable to other women in Venice. In everyday life a migration of gestural codes occurs in the learned gestures of class status and gender performance in public spaces in ways that should prove recognizable and acceptable. But Renzi's everyday aspect as a celebrity figure and independent businesswoman was extraordinary in its performance of gendered self. So, despite the prejudice against women performers, her pioneering activity up to the 1660s (her exact whereabouts and date of death after 1660 remain unknown)Footnote 127 is a legacy that highlights her importance to the story of women's liberation from oppressive patriarchy. A lasting trace that women like Renzi, and Isabella Andreini before her, left behind is their uncompromising insistence on living extraordinary lives, on their own terms, as forerunners for professional women of the future working in any roles they choose. Their celebrity status likewise marked the great divas out as phenomenal artists working on the cusp of modernity as they worked to usher it in.

Early operatic divas, imparts Daniel Freeman, enjoyed the first professional musical careers for women in public theatres in Italian-speaking lands, which enabled them to gain a level of independence and fame unavailable to other nonnoble women and to transcend class status.Footnote 128 On the operatic stage, women of low birth could portray goddesses and royalty. Moreover, when they sang cross-dressed as men, it caused them to “project a public image of indomitability or independence that few other women of their times were able to do,”Footnote 129 and the operatic profession facilitated a degree of public approval and adulation to woman singers that most women of low social class could not likely attain. On the other hand, their exalted status was tempered by the social reality that wealthy male “admirers” saw them as objects subject to “seduction and ‘possession’” and as little more than cultured courtesans.Footnote 130 In any case, Federica Ambrosini posits that the early women performers embodied “a new public role that may well have awakened the self-awareness of their female contemporaries.”Footnote 131 Women always comprised part of Renzi's audience in public theatres.