No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2009

1. British Library, Ms. Egerton 2598, fol. 82r.

2. The Derby Household Books, ed. Raines, F. R. (Manchester: Chetham Society, 1853), p. 65.Google Scholar

3. Chambers, Edmund K., The Elizabethan Stage (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951 [1923]), II, 111.Google Scholar

Cf. also Chambers, ' William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930), I, p. 35Google Scholar: ‘Perhaps [the Queen's men] never visited Scotland, as a projected royal wedding was deferred.’ The question of the visit is of special interest in view of the possibility that Shakespeare was at that time a member of the Queen's company. For a recent discussion of the theory that the young Shakespeare belonged in December 1589 to the Earl of Pembroke's troupe, and that that organization was one of two companies into which the Queen's men had split in the late 1580s, see my paper on ‘The Origin and Personnel of the Pembroke Company’, Theatre Research International, V (1979), pp. 48–68.Google Scholar

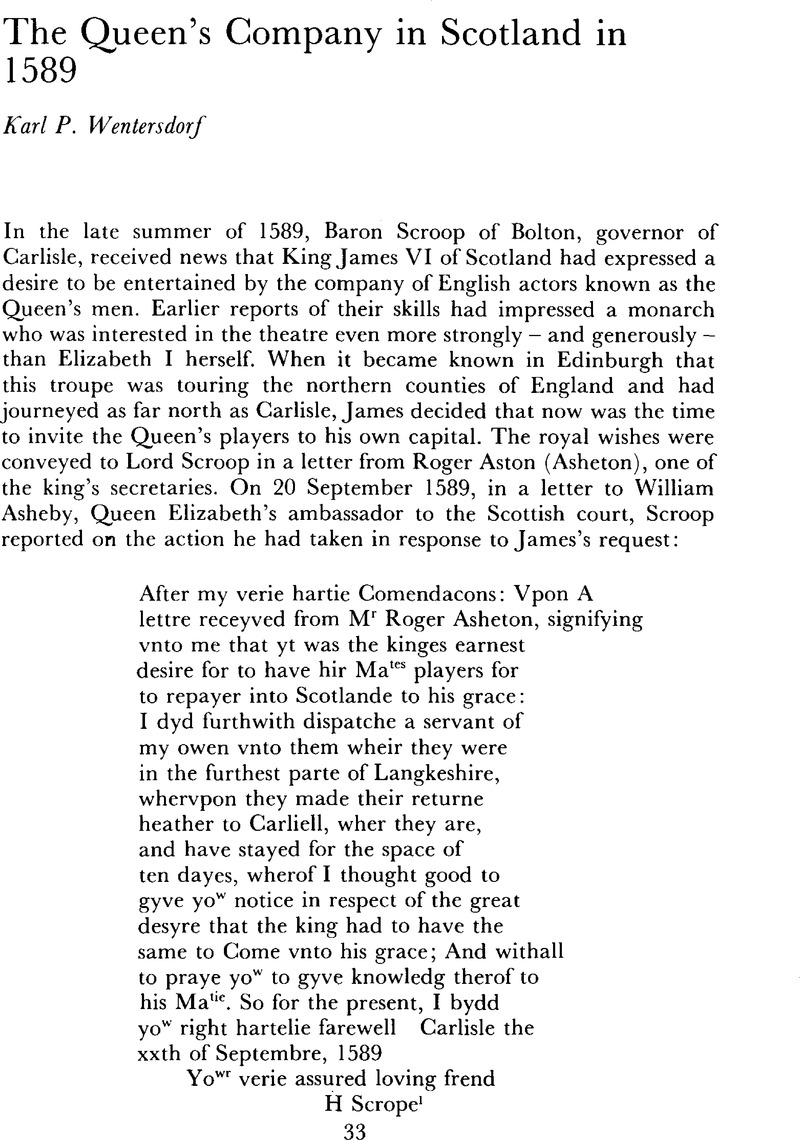

4. British Library, Ms. Cotton Caligula D. I. fol. 408r; the right-hand edge of the manuscript has been damaged by fire. An abbreviated modernized version of this paragraph appeared in The Calendar of the State Papers Relating to Scotland, ed. Boyd, W. K. (Edinburgh, 1898 + ), X, pp. 179–80.Google Scholar

5. Shortly after October, while James was abroad, Bothwell began plotting, with the aid of witchcraft, to procure the king's death; his machinations are described in the anonymous tract Newes from Scotland (London, 1591)Google Scholar and in King James's treatise on Daemonologie (Edinburgh, 1597)Google Scholar; both works were reprinted in one volume by G. B. Harrison (London: John Lane, 1924). For a discussion of the possible reflection of the Bothwell affair in Shakespeare's Scottish play, see my paper ‘Witchcraft and Politics in Macbeth’ in the forthcoming centenary volume of the Folklore Society.

6. Stowe, John, A Survey of London (1603), ed. Kingsford, C. L. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971 [1908]), I, p. 166.Google Scholar

7. See Withington, Robert, English Pageantry: An Historical Outline (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1918), I, pp. 182, 191, 202Google Scholar; Hayward, John, Annals of Queen ElizabethGoogle Scholar, cited by Jenkins, Elizabeth, Elizabeth the Great (New York: Coward-McCann, 1959), pp. 66–7Google Scholar. The royal canoneers were probably in Edinburgh again when Charles I was crowned there in 1633, since the king's progress along High Street was accompanied by peals of ordnance from the Castle (Withington, , Pageantry, p. 237).Google Scholar

8. See Pinciss, G. M., ‘The Queen's Men, 1583–92’, Theatre Survey, XI (1970), pp. 57–8Google Scholar: ‘It is doubtful that the actors ever performed before the man who was to become the next ruler of England, for his marriage festivities in Scotland were considerably delayed.’

9. The Queen's players performed before the English Court on 26 December 1589; see Chambers, , Eliz. Stage, IV, p. 163.Google Scholar