In general adult mental health services in England, there has been a recent shift from a sector model, in which the consultant psychiatrist cares for both in-patients and out-patients from one geographical area, to a model of in-patient consultants and community consultants (the functional model). Reference Dratcu, Grandison and Adkin1,Reference Khandaker, Cherukuru, Dibben and Ray2 This has provoked some debate among psychiatrists and mental health leaders. Reference Burns3 The sector model has the advantage of continuity of care in that the same consultant cares for the patient in and out of hospital. The functional in-patient/out-patient model has the advantage of avoiding many consultants feeding into an in-patient unit, with potentially better consultant leadership on wards.

Despite the heated debate, there is limited evidence to base judgements on which model might be better for patients and staff. A qualitative study identified perceived strengths and weaknesses of the in-patient/out-patient consultant model after a change from the sector model. Reference Khandaker, Cherukuru, Dibben and Ray2 In another study, Singhal et al Reference Singhal, Garg, Rana and Naheed4 asked service users and providers what they felt about a change from a sector model to an in-patient/out-patient one. Most service users and general practitioners were unaware of the change. Service providers felt that continuity of care, patient/carer satisfaction and clinical skills would be adversely affected, whereas length of stay in hospital would be reduced.

We sought to answer the following research question: is there a difference in in-patient satisfaction with psychiatrists between mental health trusts with dedicated in-patient consultants and trusts with sector consultants?

Method

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) reported on an in-patient survey of all mental health trusts in England in 2009. 5 This was a survey of people who had had an in-patient stay in acute mental health units, and had responses from over 7500 individuals. The survey asked people all about their experiences of acute in-patient mental health services along the pathway, from admission to leaving hospital, including the care and treatment they received, day-to-day activities, and relationships with staff. We used scores on the four satisfaction questions concerning psychiatrists.

-

1 Did the psychiatrist listen carefully to you?

-

2 Were you given enough time to discuss your treatment?

-

3 Do you have confidence and trust in the psychiatrist?

-

4 Did the psychiatrist treat you with respect and dignity?

The report gave a score for each trust between 0 and 100 for each question reflecting the responses of patients in that trust.

We contacted the medical directors of these trusts via email and asked whether their trust had a dedicated in-patient consultant model or a sector consultant model at the time of the CQC survey (July to December 2008). We divided the trusts into two groups (sector or in-patient/out-patient consultants) and compared the average scores on the four questions on satisfaction with psychiatrists. The average scores in each group were compared using SPSS version 13 for Windows by an independent statistician. Unpaired t-tests were used for comparisons of means.

Results

Overall, 64 mental health National Health Service (NHS) trusts had CQC survey reports on acute in-patient services; 34 trusts responded to the email query, but 3 did not want to share information on which of the consultant models they operated. Out of the 31 NHS trusts who did provide this information, 26 had a clear model of either a dedicated in-patient consultant (n = 10) or a sector consultant model (n = 16) at the time of the survey. The other 5 trusts either had a mixed model or had changed their model during the period of the survey. Only the 26 trusts that had a clear dedicated in-patient consultant or a sector consultant model at the time of the survey were included.

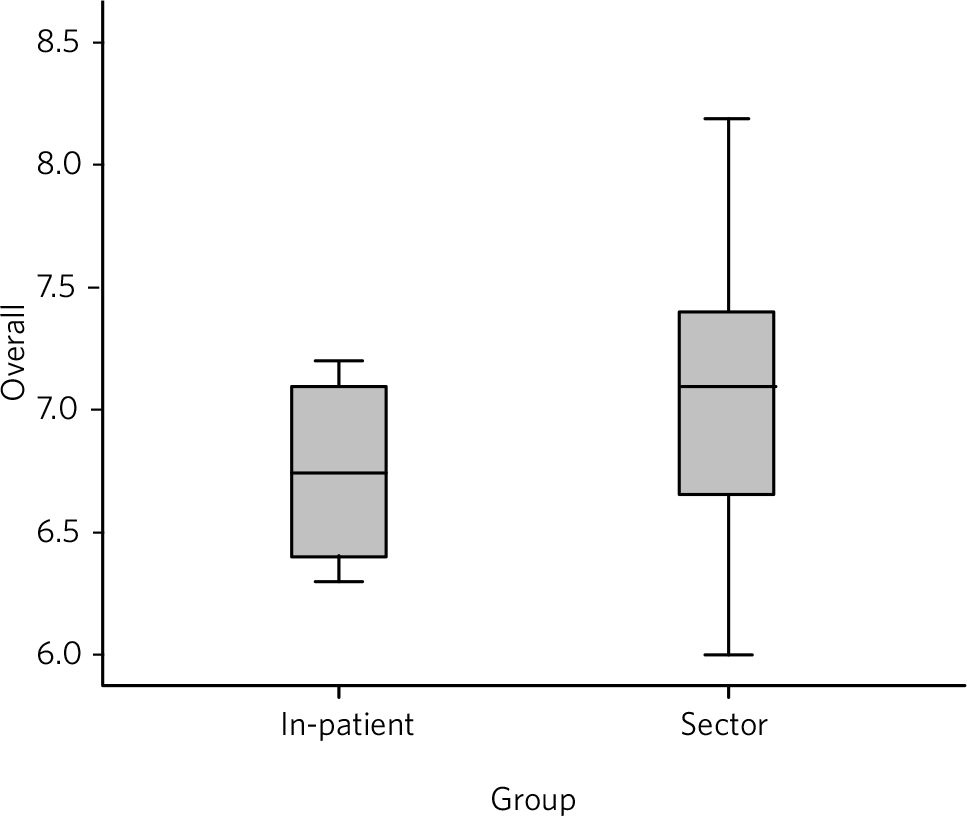

The results of the survey are presented in Table 1. The mean satisfaction scores for each question oscillated around 6-8 (where 0 was the worst possible score and 10 was the best). On only one question (number 4) did the difference between the two models of service reach the 5% significance level at 0.011. When calculating the mean score for all four questions for the two groups (Fig. 1; 0 – worst possible score, 10 – best possible score), the difference reached near significance at 0.06 (two-tailed t-test, equal variance not assumed).

FIG 1 Plot for mean scores on all four questions, comparing trust with sector consultants and those with in-patient consultants.

TABLE 1 Statistical results of the 4-question survey on patient perception of psychiatrists in 26 National Health Service trusts in England and Wales

| In-patient/community model n=10 |

Sector-based model n=16 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Mean (s.d.) | s.e.m. | Mean (s.d.) | s.e.m. | P Footnote a |

| 1 Did the psychiatrist listen carefully to you? | 6.96 (0.40) | 0.129 | 7.23 (0.62) | 0.155 | 0.193 |

| 2 Were you given enough time to discuss your treatment? | 6.26 (0.353) | 0.111 | 6.64 (0.857) | 0.214 | 0.127 |

| 3 Do you have confidence and trust in the psychiatrist? | 6.17 (0.665) | 0.210 | 6.49 (0.669) | 0.167 | 0.243 |

| 4 Did the psychiatrist treat you with respect and dignity? | 7.67 (0.316) | 0.100 | 8.06 (0.399) | 0.099 | 0.011 |

| Overall for all four questions | 6.73 (0.359) | 0.114 | 7.11 (0.614) | 0.153 | 0.06 |

a. Two-tailed t-test, equal variance not assumed.

It is interesting to observe that the standard deviations are higher for the sector model, which may suggest that the sector model might lead to a greater variability in performance of consultants.

Discussion

These findings suggest a trend towards in-patient satisfaction for consultant psychiatrists working in a sector model rather than the functional in-patient/community split model. Only one question reached a statistically significant difference at a 5% level, but the trend was consistently in favour of the sector model (Table 1).

There are clear limitations to this study. The research used secondary data from a national survey, and the limitations in this survey must be taken into account along with the limitations in our own method. The performance of the psychiatrists was not necessarily directly related to the model of consultant care, and there may be confounding factors influencing the levels of satisfaction in psychiatrists. For example, more rural areas may have kept the sector model for reasons of distances travelled in the community (as we have in Cornwall) and patient satisfaction may be greater in rural areas as morbidity tends to be less severe. The model may be more appropriate for urban areas, where distances are small and the pressure on wards can be higher. These results are from 26 out of 64 NHS trusts in England, although there is no reason to believe the other trusts would be different to those that responded. The trend to better patient satisfaction for the sector model did not reach statistical significance in four of the five calculations. This may be a type-two error due to the small sample size.

The study presents some implications for practice. It is possible that the sector model encourages better communication with patients. We can hypothesise that sector consultants know in-patients and their families well from their contact in the community, and so trust and respect are often well established and a therapeutic relationship does not have to be built from scratch. It is also possible that the continuity of care encourages consultants to treat patients better and invest more time in the therapeutic relationship, as they will be seeing them in the future in the community. In-patient consultants may have less motivation to establish rapport if they are not responsible for future care in the short to medium term. In primary care, having a longer relationship with a physician is related to a greater therapeutic quality in the relationship. Reference Noyes, Kukoyi, Longley, Longbehn and Stuart6

The implication for policy is that pushing ahead with a change from sector consultants to the in-patient/community consultant split may not be in the best interests of patients in respect of in-patient satisfaction. A change in service delivery, which always costs money in professional time, should be expected to improve a service in some way. There may be other advantages, such as better consultant leadership on wards, but this claim would need to be backed by evidence. Ideology-based health policy is fraught with dangers.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jo Palmer for statistical advice and help.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.