Measurement of the quality of services and especially the satisfaction with the individual clinician has for a long time been an elusive discipline fraught with misconceptions and conclusions based on the most tenuous evidence. Reference Shipley, Hilborn, Hansell, Tyrer and Tyrer1 There is, nevertheless, a general consensus that satisfaction, as well as dissatisfaction, Reference Barker, Shergill, Higginson and Orrell2 with the therapeutic relationship between clinician and patient is of pivotal importance in the outcome not only in the psychiatric services, but also in other branches of medicine. Reference McGuire, McCabe and Priebe3 As Western governments over the past decade increasingly have attempted to rate the quality of the individual practitioner's performance, 4 a number of non-validated scales have been used to support practitioners in their appraisals. In this way, politicians and managers can claim that service users have been included in the evaluation of the health service. Reference Andersen5 This practice is at best flawed and at worst directly misleading, Reference McGuire, McCabe and Priebe3,Reference Horgan and Casey6 and does not serve the interest of the employer, practitioner or patients.

Feedback from satisfaction surveys is an important component of performance evaluation and a tool for improving care. Patient feedback can help the practitioner to identify problems in the process of care - not necessarily directly attributable to the practitioner - and stimulate review and improvements of practice behaviour. Reference Haig-Smith and Armstrong7,Reference Rosenheck, Stroup, Keefe, McEvoy, Swartz and Perkins8 This is particularly relevant at a time when ‘consumer choice’ is high on the agenda in the debate about health issues. Reference Barker, Shergill, Higginson and Orrell2,Reference Haig-Smith and Armstrong7 Although Barker and colleagues have developed a satisfaction scale for the use in psychiatric patients that has been applied in a number of studies, Reference Barker, Shergill, Higginson and Orrell2 there still appears to be an urgent need for an easily accessible and validated scale that can be used not only to review practitioners' performance but also to collate the results of the wider services in order to improve standards.

Considering the absence of a validated scale for the use in clinical settings, the aim of this study was to produce a patient satisfaction scale that is sensitive to the individual clinician's performance, and that is easily understood and completed within a minimum time by the service user.

Method

The questionnaire was developed in a rural and inner city area of southern England, with individuals attending psychiatric out-patient clinics. All patients were informed about the purpose of the study.

Phase 1

A total of 119 patients were asked to write down an unlimited number of factors that they found important in the encounter between practitioner and patient based on their personal experience; 100 responded. They were given written information about the study and asked to leave their comments with the secretary at the local mental health unit. The patients were recruited systematically from a general, adult out-patient clinic in January and February 2006. No selection was made in order to make the scale useful for the widest possible range of attendees to psychiatric out-patient services. The participating patients' diagnoses covered a wide spectrum of psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance misuse and anxiety disorders, but these were not systematically collected. On average, each patient identified six key elements of satisfaction.

Scale development

The comments were analysed and divided into categories according to content. A literature search was also carried out and relevant literature critically assessed using criteria for evidence-based medicine with the purpose of finding key elements for the scale. Medical, nursing, social workers and patients' organisations were contacted to ascertain their views on the items identified; they gave consistent support for their use of this scale.

Phase 2

From the statements obtained from the patients in phase 1 we produced 40 questions, depending on the number of times an issue was raised. The information gathered from other agencies acted only as comparison. If an issue was mentioned by 15 or more patients, it was turned into a question. This was thought to result in a manageable number of questions for the next phase and allow us to obtain key questions that concerned a significant number of the patients involved. The consistency of the statements between the 100 patients was remarkable - only 9% of the statements could not be placed into one of the subcategories. The statements from phase 1 placed themselves into the six subcategories and therefore the 40 questions were also divided into the same categories:

-

1 trust

-

2 communication

-

3 exploration of ideas

-

4 body language

-

5 active listening

-

6 miscellaneous.

We then asked 30 new patients (March 2006) to rate the relevance of the 40 questions on a 5-point Likert scale.

Two questions were deemed difficult to understand or ambiguous by the patients. The remaining 38 questions were then cut down to 19 items depending on the total score of relevance they had received from the patients. The higher the total score, the more likely the question was to ‘survive’ into the final 19 items. We felt that those 19 items still covered most of the original statements from phase 1 without duplication. The items remained divided into the six categories and could be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, do not know, disagree, strongly disagree). This approach has been used in similar studies, for example by Rider & Perrin. Reference Rider and Perrin9 In addition to the 19 items, age and gender were included in the scale to look for age- and gender-based variations in satisfaction. Finally, an open question (‘How do you feel the practitioner could improve?’) was added at the end to give the patient an opportunity for additional comments (the patient satisfaction form is available as an online supplement to this paper).

Phase 3

In May 2006, another 44 patients were asked to complete the final patient satisfaction (PatSat) scale and the subscale of the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (VSSS) Reference Ruggeri, Lasalvia, Dall'agnola, Tansella, Van Wijngaarden and Knudsen10 after seeing one of seven psychiatrists in the out-patient clinic. The score sheets were handed out by a secretary at reception to make the procedure less intimidating. The subscale of VSSS that was used to correlate with PatSat was the ‘Professionals’ skills and behaviour' subscale. The VSSS is the overall service satisfaction scale that contains six subscales. Patients were asked how long it took them to fill in the forms. The scales were not scored in any particular order. Care was taken to ensure that the patients participating in phase 3 had not taken part earlier on in the study. Patients were not informed about the origin of the scales to avoid bias.

Analysis

Mean and standard deviation for the total scores were calculated for the VSSS and final PatSat scale. Principal component analysis was done for the 19 items of PatSat to look for dimensions in the scale. Cronbach's alpha was estimated for subscales of PatSat to assess internal reliability. Validity of PatSat was tested by performing Spearman's rank order correlation with VSSS subscale scores. The sample size to detect a correlation of 0.5 as against no correlation with double-sided alpha of 0.05 and power of 90% was 37. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 13 for Windows.

A test-retest analysis was carried out on 18 new patients to measure correlation over a 2-week period.

Results

Both scales were completed by 44 patients, 43.2% females and 56.8% males; 25% were less than 30 years old, 56.8% were aged between 31 and 50 years and 15.9% were aged over 50 years. There was a high ceiling effect in the ratings for both scales with minimal variance. The mean scores were 44.9 (s.d.=6.9) for the VSSS subscale and 84.43 (s.d.=13.9) for PatSat.

Principal component analysis of the 19 items of the PatSat scale extracted a single component of eigenvalue >1 explaining 84.2% of total variance, indicating that the scale is homogeneous and all items measured a single dimension (i.e. satisfaction).

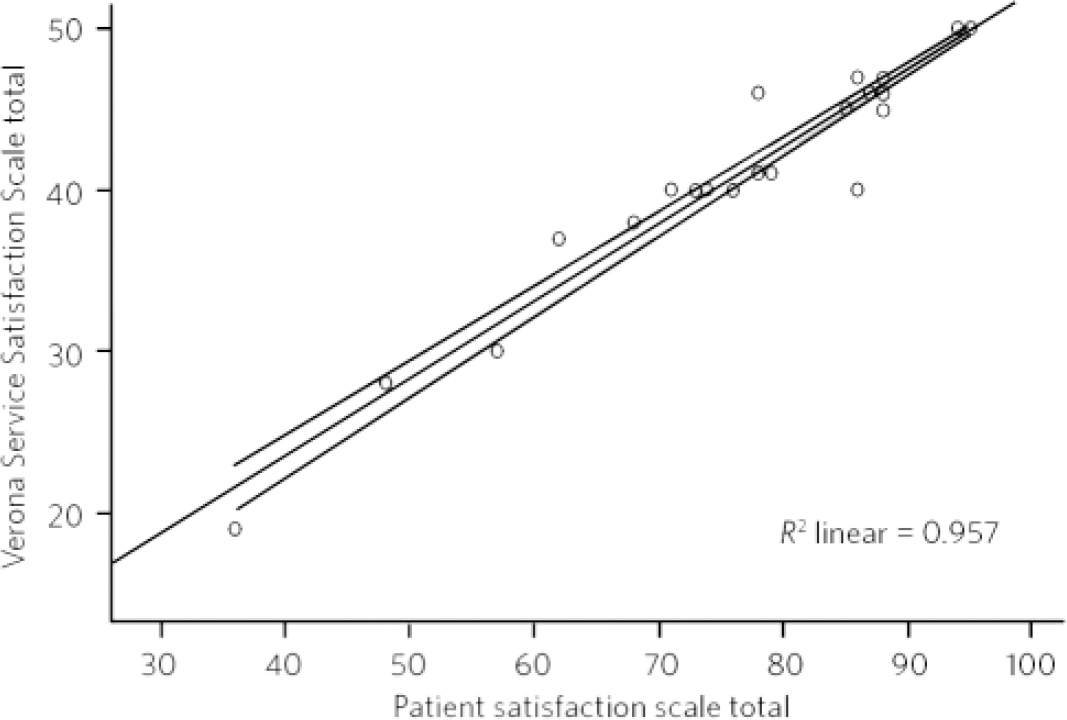

Cronbach's alpha for internal reliability of PatSat subscales was 0.98, which indicates a very high internal consistency. Spearman's rank order correlation between the VSSS and the PatSat scale was 0.97 (two-tailed P=0.001) and hence the two scales are highly correlated (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Spearman's rank order correlation comparing Verona scale and PatSat scale.

The final open question, ‘How do you feel the psychiatrist may improve?’, was answered in just over half of the surveys (53%).

Filling in the questionnaires was measured. On average, the PatSat took under 1 minute and the VSSS took 2 minutes and 20 seconds. Out of 44 patients in phase 3, 42 stated that they preferred the PatSat scale.

The test-retest procedure of the rating scale using Bland-Altman analysis showed that there was a difference of 1.2 points between the total scores at time point 1 and time point 2, with a 95% range of the difference of 5.50 and 7.83. A Spearman's analysis between the two time points shows a Spearman's rank correlation coefficient of 0.953, which is highly significant (P<0.001).

The Flesch Reference Flesch11 reading ease calculation was carried out. The score of 59.4 found in the PatSat indicates that 8th grade student can easily understand the text. Similarly, the Flesch-Kincaid Reference Kincaid, Fishburne, Rogers and Chissom12 grade was 6.1, further supporting the easy readability of the PatSat.

Discussion

A highly significant correlation was found between the PatSat scale and the VSSS. The relationship between practitioner and patient has over the past years been pushed up the agenda in many Western societies. 4 This, unfortunately, has not been followed by a surge in the number of measurement tools that patients find acceptable and understandable. There are few measurement tools that convey a valid picture of the patient's level of satisfaction with the practitioner. Reference Barker, Shergill, Higginson and Orrell2 The PatSat scale appears to live up to these standards. Furthermore, PatSat was indicated as the preferred scale by 42 out of the 44 patients in phase 3 mainly due to the simplicity and a general feeling that it covered the areas they felt were important. Filling in the form took on average less than 1 minute, unlike the VSSS which took more than double the time. The test-retest analysis provided acceptable evidence for consistency over time. The Flesch scores indicate that the PatSat is easily readable and understandable even for people with few years of education.

Some clinicians perceive satisfaction profiles as a threat to their sense of judgement, competence and autonomy. Practitioners often focus on technical ability and appropriateness of the care, whereas it has repeatedly been shown that what most highly correlates with patient satisfaction are the clinician's interpersonal skills. Reference Andersen5 The patients' choice of items (phase 1) in this study was to a very high degree in line with previous literature on the subject. Reference Barker, Shergill, Higginson and Orrell2,Reference Horgan and Casey6,Reference Maffari, Shea and Stewart13-Reference Burns, Auerback and Salskovski16 These statements were furthermore strikingly similar between the different patients, which underlines the communality in patients' hopes and expectations across the diagnostic spectrum. Communication has especially been singled out as key to avoid complaints and malpractice claims. Reference Haig-Smith and Armstrong7,Reference Richards14 It was nevertheless remarkable that not a single of the initial statements (in phase 1) mentioned the practitioner's technical abilities. Consequently, no such item was put on the PatSat scale, unlike the VSSS. It is possible that patients take the practitioner's qualification for granted but the finding opens the discussion about re-prioritising medical training, with more emphasis on communication skills.

Levels of satisfaction should not necessarily be confused with the wider concept of quality of the services; satisfaction is first of all just one of several factors that together constitute quality of the overall service on offer. Reference Andersen5 Second, satisfaction is much dependent on the patient's expectation at the outset, which in turn is dependent on the sociodemographic and diagnostic mix (especially chronicity of symptoms) of patients. Reference Rosenheck, Stroup, Keefe, McEvoy, Swartz and Perkins8 Many service users are unaware of the potential alternatives to the service they are experiencing.

However, without acceptable levels of patient satisfaction the quality of services would collapse. Reference Richards14 It is possible that measuring and responding to patient satisfaction can become a therapeutic process in itself as it indicates respect and a willingness to listen to patients' needs. Reference Ruggeri, Lasalvia, Dall'agnola, Tansella, Van Wijngaarden and Knudsen10 Patient satisfaction is an area that we as clinicians and health providers ignore at our peril.

Limitations

Limitations to the study are general reluctance to give negative evaluations of the practitioner, especially if this is your own doctor. Reference Steine, Finset and Laerum15 This is relevant here as the majority of the phase 3 results were very positive, the so-called high ceiling effect. Geographical bias must also be considered as all the patients were recruited in a rural and inner city area in southern England. Diagnoses were not specifically collected to make the scales as widely applicable as possible, but the out-patient clinic used was typical of those in such areas. Very few patients refused to participate at any of the three phases but it is possible that important information was missed out in phase 1 from the patients refusing to give their statements. These patients were likely to have held different views from the rest of the patient population. Refusal to participate is likely to be one of the main factors that make accurate patient satisfaction measurement problematic. It is possibly also the reason for the high ceiling effect that is seen in this study as well as in most other patient satisfaction studies.

This new, brief satisfaction scale enables us to quantify the complex and multidimensional relationship between the clinician and the patient seen from the patient's perspective. A highly significant correlation was found between the VSSS and the PatSat scale. The PatSat scale can be used without prior training for the practitioner and with a minimum of instructions to the patients. There was a high degree of satisfaction between the patients with the PatSat scale. So far the scale has only been validated for out-patient use but future research should be looking into validating the scale in other psychiatric settings and possibly also in other branches of medicine.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.