Claire Hilton makes very valid points about the National Dementia Strategy, 1 and many practitioners will sympathise with them. However, we may need to adopt a long view of the potential of any current initiative, because the implementation of policy can have a long gestation. The polyclinics now appearing in England were first mooted in the Dawson Report of 1920. The National Health Service (NHS) - as a system of medical care free at the time of need - began to appear in 1911 with the creation of the ‘panel’ that gave men of working age free access to general practitioners. Free access to medical services extended gradually and in piecemeal ways so that two-thirds of the population was receiving generalist and some specialist care, free by 1939, when the outbreak of war prompted the nationalisation of the hospital network. The NHS Act of 1948 rationalised a system already brought into a messy kind of existence by cumulative public and professional pressures.

Apart from the rapid uptake of new medication and some technologies (such as ultrasound and day-case surgery), most change in the NHS is slow. Nevertheless it occurs, because of what practitioners do and what the public wants. Multiple changes in routines, customs, practices and ways of working accumulate (sometimes in unexpected ways) and break the framework of rules, funding arrangements and organisational structures that we take for granted. Reference Unger2 In this kind of policy development we have to live with the facts that outcomes cannot be predetermined with any accuracy, that unintended consequences can weigh more than intended ones, and that policy implementation is fuzzy and messy. So Claire Hilton may be right that the National Dementia Strategy is a damp squib, but equally it may be too soon to tell. Thinking through her concerns might give us some clues about what we can still do to turn the strategy into tactics.

Making progress

There are a number of starting points that most seem to agree about, each with implications for how professionals work. First, the standard of dementia care in England is in urgent need of improvement, with frequent failure to deliver services in a timely, integrated or cost-effective manner to support people with dementia and their families to live independently for as long as possible. 3 Putting this right demands a higher level of collaborative working across disciplines and agencies than hitherto, and a focus on creating integrated dementia care services, Reference Bullock, Passmore and Iliffe4 either in virtual form (through local agreements to work together) or in the shape of the joint clinical directorates as advocated by the National Service Framework for Long Term Conditions. 5

The steady fall in the number of long-term care places available for people with dementia, together with the rising numbers of older people, will lead to an increased demand for complex care packages for frail older people to allow them to live independently and to postpone or avoid altogether the move into institutional care. How these complex care packages are delivered is to be decided, but the limited resources available to older people's services in local government is forcing both health and social services to do some creative thinking, and accounting, notably around self-directed support.

The apparent tardiness in the diagnosis of dementia (especially in general practice), plus professional enthusiasm for early intervention (especially among old age psychiatrists) have put earlier diagnosis on the policy agenda. Diagnosis of dementia in general practice has been incentivised by the Quality and Outcomes Framework, although this has yet to produce any great change in diagnostic rates. This may not be surprising, given the multiple perceived disincentives to recognise and respond to dementia. Reference Iliffe and Manthorpe6 However, attitudes are changing and in my view timely diagnosis is likely to occur more often as specialist assessment and support services become more visible.

Dementia care requires skills rather than job descriptions. The National Dementia Strategy reflects this understanding by focusing on competencies, but service providers may still think in terms of jobs and roles. Wise commissioners will be looking to use the expertise in care-home staff and social work to make dementia care work more efficiently. Reference Iliffe and Wilcock7 Old age psychiatrists will be acting in their own interests if they plan to transfer diagnostic and management skills to general practitioners in their localities, in a way that is practically manageable, over a period of years. There is also a need (clearly identified in the strategy) for hospital in-reach to help hospital staff work more effectively with patients with dementia, although this may be a harder task.

Existing plans for reducing the community burden of heart and circulation disease may also help to protect brains. Cardiovascular risk factors predict the likelihood of developing dementia more than many professionals realise. Hypertension and type 2 diabetes increase the risk of developing dementia sixfold, and obesity is a risk factor for dementia independent of blood pressure and diabetes. Cognitive function changes are measurable in people with cardiovascular risk factors in middle age, making targeted primary prevention of both heart and brain disease imperative. There is the real possibility that vigorous control of cardiovascular risks at community level could postpone the onset of dementia syndrome, and there is already some evidence of this happening in the USA. Reference Langa, Larson, Karlawish, Cutler, Kabeto and Kim8 No similar pattern is obvious yet in the UK, Reference Langa, Llewellyn, Lang, Weir, Wallace and Kabeto9 but this may be a time-lag effect, and we may see the incidence of dementia fall.

Addressing these issues does not necessarily require substantial extra resources, if small changes can be encouraged and maintained over time. A great leap forward, on the other hand, would need investment on a large scale, which in the financially constrained NHS of the near future is likely to find expression as another round of pilot projects with limited resources - the familiar problem of ‘multiple pilotitis’. Taking the former approach may prove difficult; the NHS sometimes prefers speedy action without too much thought behind it, whereas implementing the strategy requires detailed discussion and debate, and local tailoring. One place to start that debate is around the unintended consequences of implementing new policies.

Unintended consequences

The demographic changes in the population will increase the prevalence of dementia, but the impact of this can be overstated, and there is a tendency to apocalyptic terminology as pressure groups and interests combine to raise the political profile of dementia for their own reasons. This becomes clearer if we consider, for example, the impact of the National Dementia Strategy on a real urban primary care trust in a formerly industrialised area. The trust covers a population of 215 000 people with average demography, mixed ethnicity and a prevalence of dementia of 1 in 14 in people aged 65 years and over, and 1 in 6 in people aged 80 years and over. About 250 people a year die with dementia in the trust's area, which has a higher than average proportion of older people living in residential care but relatively few ‘dementia home’ places. Uptake of home care services is high, but with relatively small packages and low unit costs.

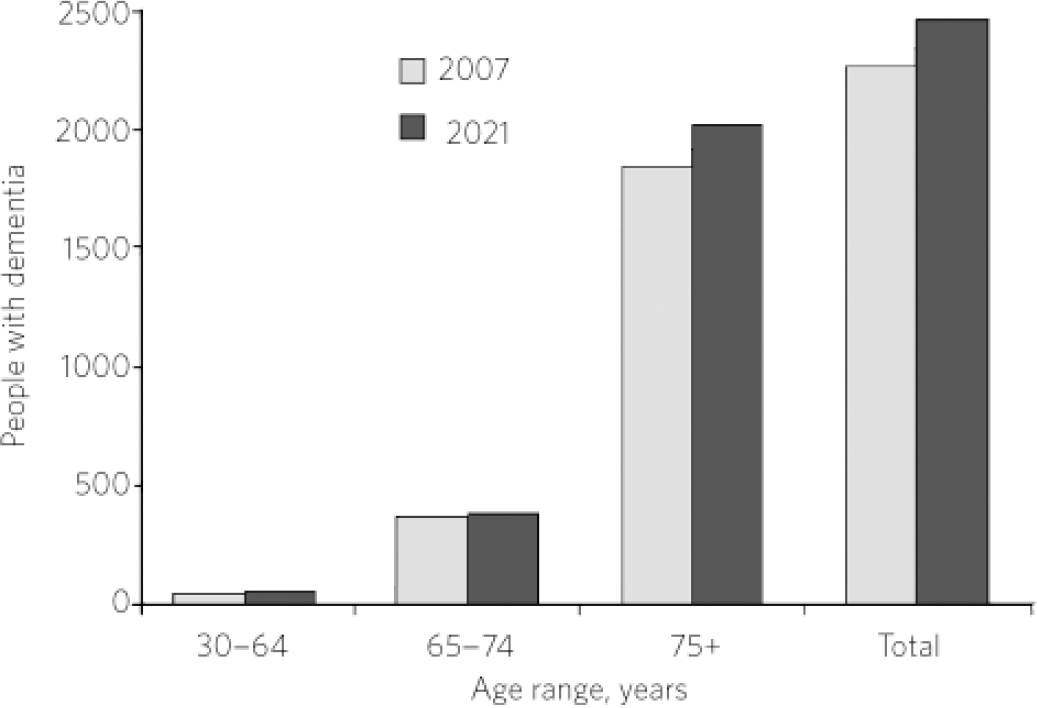

Figure 1 shows the likely increase in dementia prevalence in this area between 2007 and 2021. The absolute increase in numbers of people with dementia is about 200, which seems as if it should be manageable, possibly with no increase in resources if there is any slack in the system. This is an optimistic scenario, because the National Dementia Strategy is seeking earlier diagnosis, which would increase memory clinic activity and increase survival time and service use. Given that half of all people with dementia are not yet known to services, increasing the diagnostic efficiency of general practitioners and specialist clinics could reveal more people with dementia than the simple figures suggest. Instead of the numbers rising from 2200 to 2400, they might rise from the 1100 known to services to a much larger figure. This is the ‘worst case scenario’. Not all people with dementia are ‘known’ to services, for the good reason that their declining cognitive function does not yet produce significant dislocation of everyday life for them or their families. In the absence of any effective therapy that would modify the course of dementia there is no case for seeking them out. Although this limited therapeutic potential may change, given the number of drugs in development, Reference Kramp and Herrling10 there is no certainty that disease-modifying agents will become available in the next few years, and no sensible strategy can be built on their appearance. Similarly, there are perverse incentives not to ‘know’ that an older person has dementia. Octogenarians who are admitted to hospital in an emergency after falling and breaking a hip will have their postoperative confusion attributed to the trauma of surgery and the temporary disorienting effect of the anaesthetic, and this will allow them to proceed through rehabilitation, and if necessary into residential care, in ways not available to patients with dementia. Outcomes for the patient can be better if the diagnosis is tacitly avoided by all concerned, especially in our urban primary care trust with its limited number of dementia home places and its relatively sparse home care support. Again, this may change because in-reach of dementia services alters the culture of care in acute trusts, but this is also likely to be a long drawn-out process.

Fig 1 Number of people with dementia in an urban primary care trust: comparison of 2007 figures with projected numbers for 2021.

Care homes and palliative care

Implementing the dementia strategy at local level may require attention to care homes because of current concerns about their capacity. We know that diminishing care home availability will entail greater community provision, but also care home viability may be threatened by policies that enable more people to remain at home in situations that are not burdensome to themselves or their caregivers. The implications of the continual decline in care home places, especially among small-scale providers, could be considered as part of the process of managing the changes sought by the National Dementia Strategy. Will almost all care homes become homes for people with dementia, or with life-threatening conditions, or places where palliative care is delivered? What would be the implications of a having a residential and nursing home sector that was more oriented to palliative care for people with dementia?

Is there a case for linking care homes to primary care services so that the gap between primary care professionals and care-home staff does not continue to widen? One model that might be useful for commissioners to consider is whether or not there should be tighter agreements between care homes and joint commissioning services about what is expected and how this might operate over the medium term. Care homes may wish to provide services for local areas in different ways and we should not expect one size to fit all, but we should expect the engagement of dementia services with them.

Conclusion

The National Dementia Strategy embodies a political commitment made by the government to an ageing society, and is the result of a long period of agitation and lobbying. There is no guarantee that its proposals will be implemented, given the vagaries of economies and the frailty of political will, but all of them can be. We should aim for slow, cumulative changes that produce qualitative shifts in the standards of dementia care.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.