Up to 5% of people attending accident and emergency (A&E) departments present with primary psychiatric problems, and another 20–30% have psychiatric symptoms in addition to physical disorders. Reference Ramirez and House1 The most common presenting psychiatric problem in A&E departments is usually self-harm, typically constituting a third of psychiatric presentations. Reference Bolton2 The national male and female rates of self-harm in Ireland in 2005 were 167 and 230 per 100 000 respectively. 3 The incidence of self-harm exhibits marked variation by geographical area: the highest rate has been observed in the Health Service Executive Dublin North East Region, 21% and 27% higher than the national rates for men and women respectively. 3 Beaumont Hospital is one of the hospitals in this region.

A psychosocial assessment can be defined as an assessment conducted by a member of a mental health team who has been trained in the process, and covers the assessment of such factors as the cause and degree of suicidal intent, current mental state and level of social support, psychiatric history, personal and social problems, future risk and need for follow-up. Reference Gunnell, Bennewith, Peters, House and Hawton4 It has been reported that a psychosocial assessment reduces the repetition rates of self-harm by up to 50%. Reference Kapur, House, Dodgson, May and Creed5 However, the provision of psychosocial assessment in many hospitals remains poor. Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie6 A psychosocial assessment was undertaken in only 54% of people attending four UK teaching hospitals following self-harm. Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie6

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines developed in 2004 recommend that:

-

• everyone presenting following self-harm should receive a psychosocial assessment;

-

• these individuals are treated with the same care, respect and dignity as other patients;

-

• appropriate training is provided to clinical and non-clinical staff who have contact with people who have self-harmed;

-

• a preliminary psychosocial assessment is offered to all self-harm patients at triage; this assessment should determine the person's mental capacity, willingness to remain for further (psychosocial) assessment, level of distress and the possible presence of mental illness;

-

• medical treatment is offered even if the person does not wish to receive a psychosocial or psychiatric assessment. 7

We sought to examine the self-harm attendances at Beaumont Hospital A&E department over a 12-month period with the aim of identifying the provision of psychosocial assessments in a socioeconomically deprived population and investigating whether the NICE guidelines were being complied with.

Method

The Beaumont Hospital A&E Register was studied to identify all patients who attended the A&E department with a presentation indicative of self-harm over a 12-month period between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2006. The Register records the name, address, date of birth and reason for attendance for every individual who presents to the department. The A&E case notes were located for each presentation indicative of self-harm. Cases were excluded if the presentation was found not to be due to self-harm. A total of 834 self-harm cases were identified over the 12-month period. From the case notes, data were collected on demographics, the triage assessment, whether medical treatment was offered and the provision of a psychosocial assessment. We also clarified with staff and management as to the training provided to staff who have contact with people presenting following self-harm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 15 for Windows. For dichotomous variables, chi-squared tests were used to determine differences in proportions. Binary logistic regression was used to investigate the factors influencing the likelihood of a psychosocial assessment being undertaken.

Results

Hospital characteristics

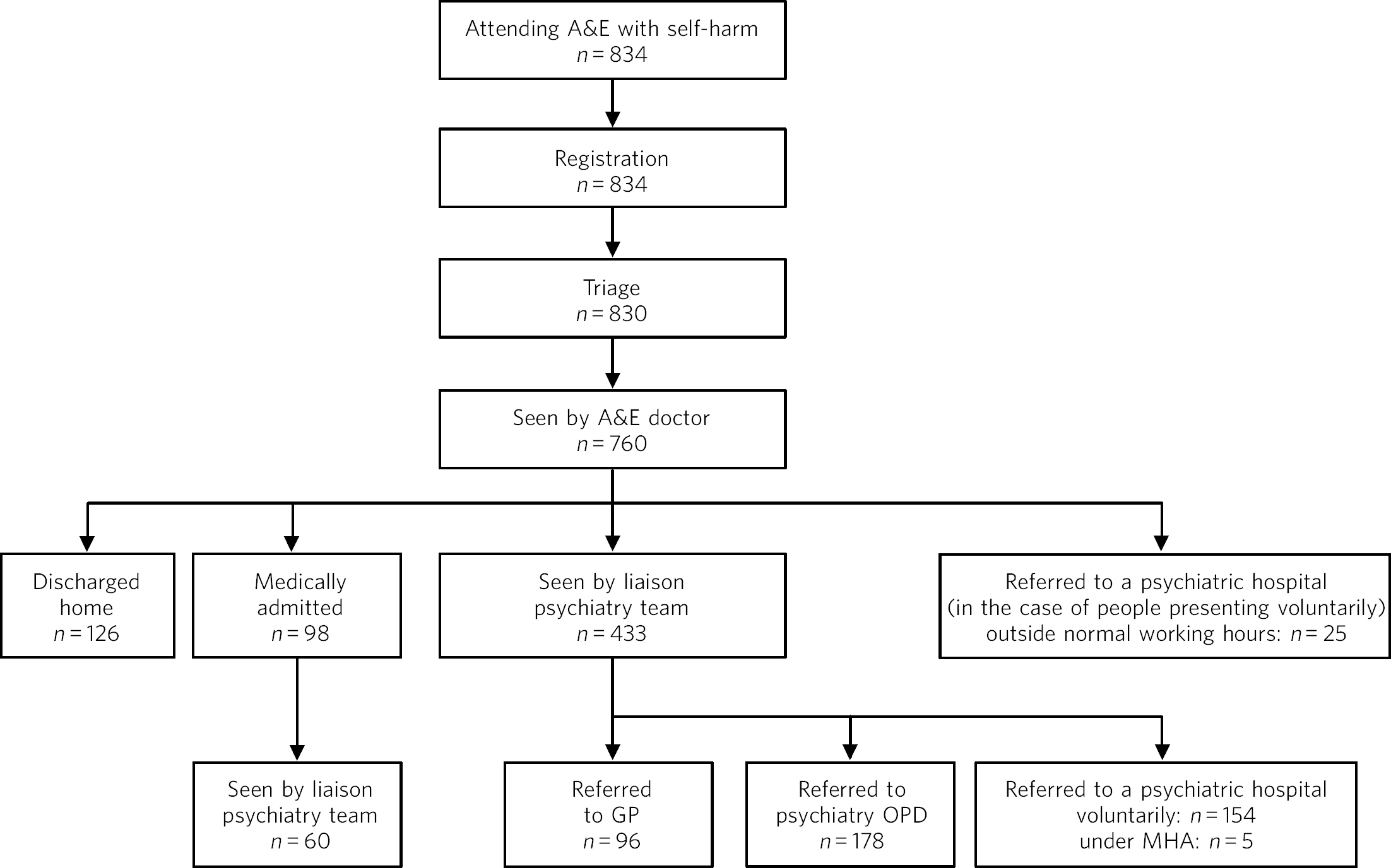

Beaumont Hospital has 720 beds and is one of the largest general hospitals in Ireland, providing acute hospital care for the north Dublin area, a region of significant socioeconomic deprivation. The A&E department has a catchment area of over 250 000 people. An average of 60 patients per day are admitted for trauma or elective treatment, making it one of the busiest general hospitals in Ireland. The department of psychiatry provides a consultation liaison psychiatry service for the A&E department and the general hospital. The hospital does not have an in-patient psychiatric unit. Psychiatry cover is provided for the A&E department and the general hospital between 09.00 h and 17.00 h Monday to Friday and from 10.00 h to 14.00 h at weekends. Figure 1 shows the sequence of events following presentation at A&E by people who had self-harmed (those who left are omitted from the figure).

Fig 1 Sequence of events occurring when people present to the accident and emergency department with self-harm. A&E, accident and emergency; GP, general practitioner; MHA, Mental Health Act; OPD, out-patient department.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

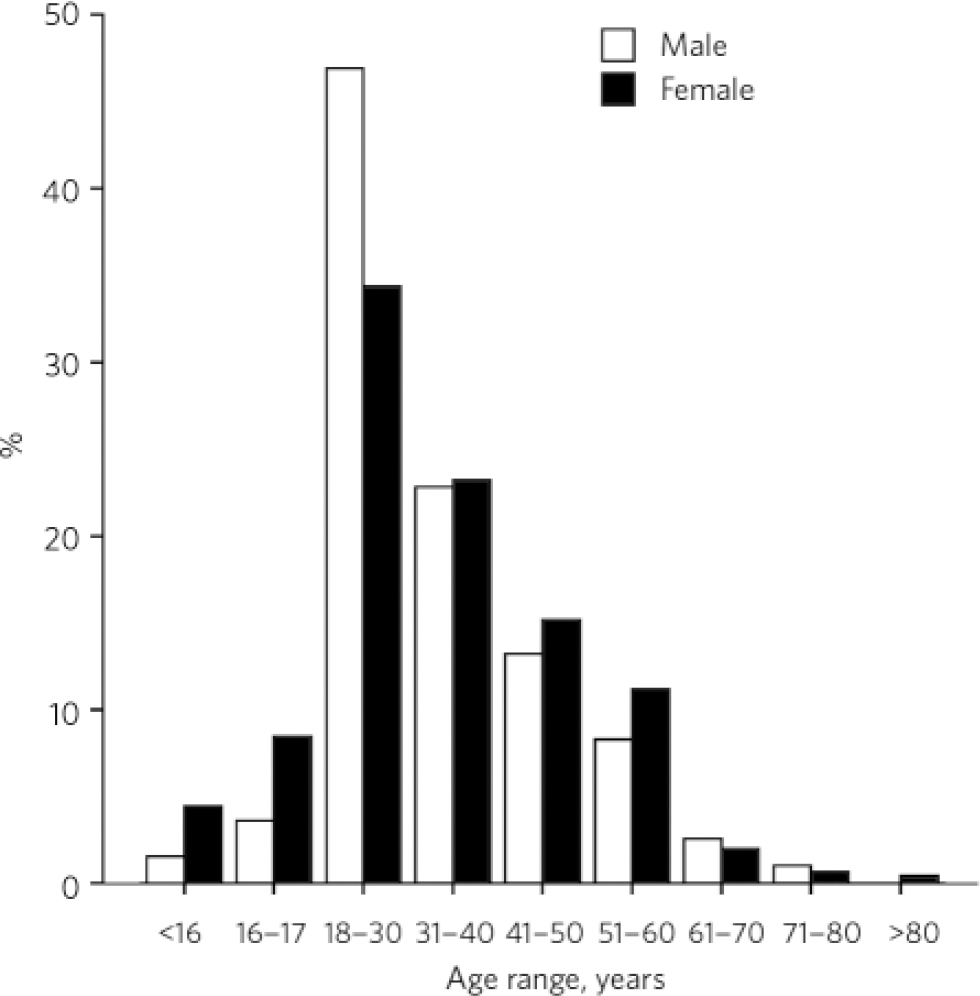

A total of 834 attendances for self-harm were made by 619 different individuals over the 12 months. More than half (54%) of those attending were male (n = 448). Of the 834 attendances, 589 (71%) were single, 159 (19%) were married and 86 (10%) were separated, divorced or widowed. The mean age was 33 years (range 14–79) for males and 34 years (range 13–89) for females. The age and gender distribution of the sample is shown in Fig. 2. The most common method of self-harm was an overdose, noted in 655 cases (78.5%).

Fig 2 Age and gender distribution of self-harm attendances.

Compliance with NICE guidelines

New medical staff receive training in the management of people presenting following self-harm as part of their first week induction programme led by the A&E consultants. The liaison psychiatry service then provides a further session within the weekly A&E medical training programme, which emphasises the importance of considering both the physical and psychological needs of these individuals. This includes recommending that people who present following self-harm are treated with the same care, respect and dignity as other service users, as well as offering them medical treatment regardless of whether or not they wish to receive a psychosocial or psychiatric assessment. Informal teaching centered around individual case discussion between liaison psychiatry and a range of A&E staff (medical and nursing) takes place on a daily basis.

The Manchester Triage System is employed by triage staff in Beaumont Hospital A&E. Reference Mackway-Jones8 In this system, highest priority is assigned not on the basis of diagnosis but rather on evaluation of the presenting complaints and symptoms using flowcharts to guide the triage nurse's approach. For individuals presenting following self-harm, their triage rating is determined predominantly by their physical needs rather than their mental state and level of distress; unless their clinical status is life-threatening, most are classified as low priority. The triage notes contained documentation of the reason for presentation to A&E (e.g. overdose, self-laceration) and whether or not the attenders expressed a desire to end their life at the time of interview by the triage nurse. The triage notes did not contain documentation of capacity or the willingness to remain for further (psychosocial) assessment. Medical treatment was offered at all 834 attendances (100%) even if the person did not wish to receive a psychosocial or psychiatric assessment. A psychosocial assessment was undertaken by a member of the liaison psychiatry team in 493 (59%) cases. Factors influencing the likelihood of a psychosocial assessment being undertaken are shown in Table 1. The proportion of episodes assessed by psychiatry was higher for female attenders (n = 274; 56%) than males and higher in those less than 45 years of age (n = 401; 81%) than in older individuals. Significantly more of those under 45 years old with a history of self-harm and who disclosed a past psychiatric history received a psychosocial assessment. The strongest association was for those who disclosed a past psychiatric history. There was no significant difference in the likelihood of receiving a psychosocial assessment between those who presented out of hours and those who presented during normal working hours. People presenting following self-laceration were 0.6 times less likely to be assessed by psychiatry than those who used other methods of self-harm (Pearson's χ2 = 6.72, P = 0.010).

Table 1 Factors influencing the likelihood of a psychosocial assessment being undertaken

| Factor | P | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female v. male) | 0.98 | 1.00 (0.74–1.34) |

| Age (<45 years v. ⩾45 years) | 0.03 | 1.53 (1.05–2.22) |

| Method (laceration v. other) | 0.01 | 0.60 (0.41–0.89) |

| Disclosure of past self-harm (yes v. no) | 0.02 | 1.44 (1.05–1.97) |

| Disclosure of a psychiatric history (yes v. no) | <0.001 | 3.01 (2.12–4.27) |

| Time of presentation (09.00–17.00 h Monday to Friday v. out of hours) | 0.32 | 1.22 (0.83–1.81) |

| Medical admission (yes v. no) | 0.67 | 1.10 (0.69–1.74) |

People who attended but did not receive a psychosocial assessment by a member of the psychiatry team in A&E are represented in Table 2. Of this group, 133 (39%) were single males under the age of 45 years, 202 (59%) had a history of psychiatric illness (Pearson χ2 = 4.82, P = 0.028) and 149 (44%) had a history of self-harm (Pearson χ2 = 21.10, P<0.001). Of those who did not receive a psychosocial assessment, 141 (41%) re-attended during the 12-month study period and 67 (48%) of these individuals received a psychosocial assessment at that time.

Table 2 People attending the accident and emergency department for self-harm who did not receive a psychosocial assessment by a member of the liaison psychiatry team

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Left after registration but before triage | 4 | 1 |

| Left after triage but before seeing an A&E doctor | 70 | 21 |

| Took their own discharge from A&E | 20 | 6 |

| Left after being seen by A&E doctor but prior to psychiatry assessment | 56 | 16 |

| Discharged home by an A&E doctor | 126 | 37 |

| Transferred to a psychiatric hospital by an A&E doctor (outside normal working hours) | 25 | 7 |

| Admitted medically | 38 | 11 |

| Left during psychiatry assessment | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 341 | 100 |

Table 3 summarises the overall level of compliance with the NICE guidelines.

Table 3 Level of compliance with the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommendations 7

| Guidelines | Compliance |

|---|---|

| Everyone presenting following self-harm should receive a psychosocial assessment | 59% |

| These individuals are treated with the same care, respect and dignity as other patients | Not measured but recommended in the training programme |

| Appropriate training is provided to clinical and non-clinical staff who have contact with people who have self-harmed | Medical staff received appropriate training as part of a training programme. However, no nursing or non-nursing staff received training as part of a structured programme |

| A preliminary psychosocial assessment is offered to all self-harm patients at triage | 100% – but this did not include documentation of capacity or willingness to remain in A&E for a further (psychosocial) assessment |

| Medical treatment is offered even if people do not wish to receive a psychosocial or psychiatric assessment | 100% |

Discussion

The provision of psychosocial assessments was noted to be significantly less than that recommended by the NICE guidelines, with 41% of those attending A&E leaving without a psychosocial assessment. This finding is in keeping with levels of 46% reported in a study of four teaching hospitals and with that of an 8-week audit of 31 general hospitals in England in which 44% did not receive a psychosocial assessment. Reference Gunnell, Bennewith, Peters, House and Hawton4,Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie6 An interesting finding in our study was that the time of presentation was not associated with the likelihood of receiving a psychosocial assessment. This could be due to that fact that people presenting out of hours with large overdoses are often very sedated and not suitable for immediate psychosocial assessment upon arrival. Hence they are seen by the liaison psychiatry team from 09.00 h the next morning. We will re-evaluate the provision of psychosocial assessment following the proposed introduction to Beaumont Hospital of a 24-hour psychiatric service available 7 days per week. Our aims include increasing the rates of psychosocial assessment, with an associated reduction in the repetition rate of self-harm. Reference Kapur, House, Dodgson, May and Creed5

As in previous research, Reference Horrocks, Price, House and Owens9 we found that people presenting following self-laceration are less likely to receive a psychosocial assessment than those who had presented following other forms of self-harm, perhaps reflecting the perceived or actual different intent behind self-inflicted cutting. This is an important issue to address in further training programmes, given the high rates of distress and repetition of self-harm.

Of the 41% who did not receive a psychosocial assessment, 39% were single males under the age of 45 years, 59% had a past psychiatric history and 44% had a history of self-harm. Each of these factors is separately associated with an increased risk of suicide.

Front-line staff in Beaumont Hospital A&E who have contact with people presenting following self-harm are provided with guidance to assist in their understanding and care of these individuals. The NICE guidelines were not met with regard to involving service users who have self-harmed in the training of A&E staff, or in the joint involvement of mental health and emergency department services in the development of psychosocial assessment training and early intervention for those who have self-harmed. Improvement of the A&E service could potentially be achieved by involving service users in A&E training as recommended by NICE and by developing a more coordinated approach between the mental health and emergency department services.

As noted earlier, the Manchester Triage System used prioritises patients' physical needs rather than their mental state and level of distress. Reference Mackway-Jones8 The use of mental health triage systems such as the Australian Mental Health Triage Scale recommended by NICE could be considered. 10 The mental health triage scale developed by Broadbent demonstrated that emergency department staff developed a greater understanding of the needs of service users with mental health difficulties and they tended to increase the priority of assessment and treatment for a number of those presenting with mental health problems. Reference Broadbent, Jarman and Berk11

The introduction of a mental health triage system could be advantageous in terms of increasing the awareness of staff with regard to the needs of service users with mental health problems, improving outcomes and decreasing waiting times. Triage staff would, however, require additional training in the assessment and initial management of service users presenting with mental health problems. The assessments undertaken by triage staff did not include documentation of patient capacity or willingness to remain in A&E. Recording of capacity and that an individual might be unwilling to remain in A&E could be important in terms of highlighting cases where the person might be a risk to themselves and where urgent psychiatric assessment might be required.

The strengths of the study include a relatively large sample size, comprising people who were clearly identified as having presented following self-harm. The study was undertaken over a 12-month period, and the same person extracted the data during this interval. Weaknesses of the study include the lack of objective data on whether or not individuals who had self-harmed were treated with the same care, respect and dignity as other patients, and that we did not access whether the guidance given to front-line A&E staff to assist in their understanding and care of people following self-harm actually increased their understanding and improved the level of care. Future studies will endeavour to evaluate these aspects more closely by providing patient satisfaction questionnaires to different groups of individuals presenting to A&E in order to determine if differences exist in the responses of people attending for self-harm in comparison with those attending for other reasons. The attitudes of A&E staff to those attending for self-harm v. other patient populations could also be studied by means of an anonymous staff questionnaire. Studies that have examined attitudes to self-harm among health professionals have highlighted that negative and ambivalent attitudes to self-harm exist among medical and nursing staff. Reference Sidley12–Reference Hemmings14

The NICE guidelines provide good practice recommendations for the management of people presenting following self-harm. This study shows that we have still some way to go to achieve these.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.