Medical practice has, in the modern era, steadily moved away from a paternalistic model of doctor-directed care towards a model of information sharing and autonomous decision making by patients. Most doctors and patients view this as both positive and progressive, ideally optimising the well-being of the patient. Within psychiatry this has been a factor in many of the changes in care from, for example, the asylum to the provision of predominantly community-based care and the introduction of mental health legislation in many jurisdictions to protect both patients and the public. Despite this ‘progress’, many patients managed by psychiatrists continue to feel coerced into a course of action they may, in fact ultimately prefer to decline, leading some to consider coercion as a necessary, if unfortunate, reality of modern community-based psychiatry.

Initiation of Mental Health Act legislation to require admission to hospital, Reference Katsakou and Priebe1 locked psychiatric wards Reference Haglund and Von Essen2 and the use of community treatment orders that require community patients to accept treatment Reference Monahan, Bonnie, Appelbaum, Hyde, Steadman and Swartz3 are examples of interventions that can be seen to reduce an individual's liberty and coerce them into accepting psychiatric management. Increasingly so, the reach of these powers in psychiatry is stretching past the hospitals' doors as community treatments become more ubiquitous. This raises the importance of a reconsideration of coercion in psychiatric care: what it is, how prevalent it is, if it is supported by evidence and what, if anything, clinicians can do to reduce its sway.

What is coercion?

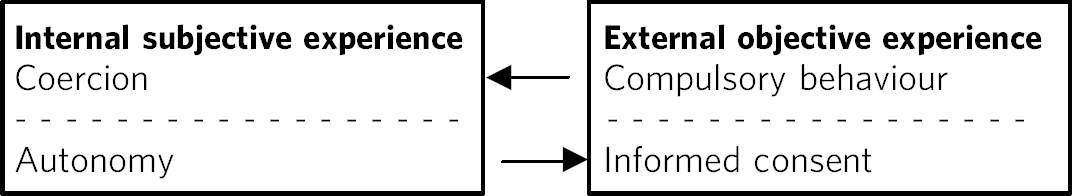

Any consideration of coercion requires a clear understanding of what coercion is, a consideration not always made in the empirical literature and debated in medical ethics. The most robust appraisal conceptualises coercion as a subjective state, within a patient, that is reached after consideration of their environment and situation. Reference Rhodes4,Reference Szmulker and Applebaum5 As such, coercion can be considered as a ‘necessary’ subjective state that arises from compulsory actions in a similar way that autonomy is the internal subjective state that is necessary to allow objective informed consent (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 The relationship between coercion and compulsion, autonomy and informed consent.

In the empirical literature this construct is often called ‘perceived coercion’ in order to mark it as separate from objective interventions that may potentially increase or decrease the prevalence of coercion. This distinction is important as there is a so-called ‘grey zone’ that exists between interventions that may force an individual to undertake a course of action and the subjective experience of being forced or threatened into such action. Reference Eriksson and Westrin6 For example, not all legally detained patients experience coercion in the action of detention, describing the process in very positive terms as making them feel safe and increasing their access to care. Reference Gibbs, Dawson and Mullen7 It is difficult to see how these individuals can be considered to be coerced into treatment.

Historical philosophical considerations

The concept of coercion and compulsion are not the focus of in-depth philosophical debate outside their sociopolitical ramifications in Western philosophy. Nonetheless, classical philosophers set out the necessary conditions for coercion and its potential moral implications in society. Although these arguments are not made considering medical scenarios (and some even exclude the ‘mentally infirm’ from their reasoning), their implications in how we conceptualise coercion and implement compulsive acts is clear.

Hobbes clarifies the necessary conditions for coercion to occur, namely one person or group in having power over another individual or group. In this environment coercion can exist. Reference Hobbes8 This view is developed by Emmanuel Kant who views coercion as philosophically in opposition to freedom. Actions that increase coercion are, however, morally acceptable when such coercion acts in the good of society as a whole. Reference Kant and Gregor9 This position is challenged by J. S. Mill who, in his text On Liberty purports:

[An individual] cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise. Reference Mill10

In essence, Mill is opposed to any limitation on self-governance; however, he does make exception in certain cases such as children and the mentally infirm on the basis that others are in a better position to ensure their good.

The importance of these historical philosophical views can be seen reflected in individual and societal practice today. In Mills' perspective the doctor fulfils the role of the person both in power and care, and the patient is potentially subject to it, whereas Kant's views are, in some respects, directly translated into most mental health legislation where the use of compulsion is morally justified on the basis of its presumed good to both the patient and society as a whole.

The modern bioethical approach

These historical concepts act as the basis for much of modern bioethics. All psychiatric interventions are designed to improve the well-being of patients who are by right considered to be able to give consent and be fully informed. This is underpinned by the ethical principle of autonomy. Reference Beauchamp and Childress11 As the practice of medicine has evolved, the principle of autonomy has become one of the essential guidelines of practice, not the doctor providing the facts and figures but engaging in a dialogue that allows a patient to make an informed choice. Reference Quill and Brody12

By definition, coercion and compulsion sit in opposition to autonomy and informed choice 13 (Fig. 1) by forcing a patient to undertake a course of action over which they have little or no control. If this is the effect of a compulsory action, the question of whether such intervention may lead to immediate harm, in opposition the principle of non-malfience Reference North14 also becomes relevant. When considering the ‘harms’ of coercion and compulsion it is the requirement to do ‘good’ that acts as a counterpoise to these bioethical concerns. In other words the consideration of any short-term coercive ‘loss’ is outweighed by the potential for ‘good’ to come in the intermediate to long term. This acts as justification for compulsory intervention that increases the likelihood of coercion. As the ability to discuss options has been put to one side and the doctor is, essentially, deciding for their patient, there is an increased burden on the professionals involved to be clear what that good is. This requires a clear understanding of the evidence both as to who might feel the effects of coercion most forcefully when a compulsory course of action is embarked on, but also the likelihood of benefit and what can be done to minimise the impact of coercion on this.

Is coercion common?

The prevalence of coercion allows us to consider whether it is rare or common and, by implication, the extent it needs to be considered by psychiatrists and policy makers. Point-prevalence rates vary considerably from as little as 10% in an American state in-patient sample Reference Hoge, Lidz, Eissenberg, Gardner, Monahan and Mulvey15 to 100% in a small Icelandic sample. Reference Kjellin, Hoyer, Engberg, Kaltiala-Heino and Sigurjonsdottirl16 Systematic review provides raw prevalence rates approximating 50%, primarily in psychiatric in-patient samples (unpublished data from 18 papers; details available from the author on request). The out-patient samples that provide dichotomous prevalence data in the community are of American mandated community treatment and have similar rates. Reference Link, Castille and Stuber17,Reference Swartz, Wagner, Swanson, Hiday and Burns18 Meta-regression modelling confirms that legal detention is the intervention most commonly associated with the experience of lived coercion in patients, although a quarter of all patients admitted informally to hospital also experience coercive treatment (unpublished data; details available from the author on request). Cultural influences play an important role with the experience of coercion eight times as common in Nordic countries compared with the USA, with other high-income Western countries between these two extremes. The causes for this intercountry variation is unclear, however it offers the opportunity for further research to uncover which variables impact on its prevalence. What is clear from this is that coercion is commonly associated with psychiatric interventions and, although legal detention is closely associated with coercion, compulsion and coercion are empirically, as well as deductively, different constructs.

Who experiences coercion most?

If coercion is common, identification of who is most likely to experience coercion allows clinicians to focus their attention on reducing coercion in target populations. Other than legal compulsion, it is not immediately obvious who is most at risk of coercion in psychiatric care.

Basic demographic data is contradictory. For example, Bindman and colleagues found positive correlations between increasing age and Black and minority ethnicity, suggesting in England at least elderly Black and ethnic minority individuals were potentially at greatest risk of being coerced. Reference Bindman, Reid, Szmukler, Tiller, Thornicroft and Leese19 Two Nordic studies, however, found contradictory correlations regarding age and gender, Reference Poulsen20,Reference Iversen, Hoyer and Sexton21 with a major American study Reference Lidz, Hoge, Gardner, Bennett, Monahan and Mulvey22 and a New Zealand study Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale23 finding Black and minority ethnicity to be protective. Similarly, contradictory evidence exists for psychopathology, Reference Monahan, Bonnie, Appelbaum, Hyde, Steadman and Swartz3,Reference Link, Castille and Stuber17,Reference Poulsen20,Reference Iversen, Hoyer, Sexton and Gronli24 satisfaction with care Reference Iversen, Hoyer and Sexton21,Reference Svensson and Hansson25 and global functioning. Reference Svensson and Hansson25,Reference Nicholson, Ekenstam and Norwood26

Social adjustment gives a better guide, with those functioning well in society most unhappy with a loss of autonomy. It is perhaps unsurprising that those who are better adjusted to living in the community feel it to be particularly intrusive to be admitted to hospital Reference Iversen, Hoyer, Sexton and Gronli24 or required to be mandated to out-patient treatment, Reference Link, Castille and Stuber17 although this insight does not reflect outcomes if such coercive interventions were not implemented.

If demographic, symptom and functioning data provide only weak associative data to identify those most likely to experience psychiatric interventions' as coercive, what other measure might help to guide clinical practice? Four studies have identified interactive processes, broadly related to ‘being heard’ that are important in the patients' experience of coercion. Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale23,Reference Lidz, Mulvey, Hoge, Kirsch, Monahan and Eisenberg27-Reference Shannon29 Using different measures, these studies all show that patients' who experienced professional staff as listening to their views as feeling less coerced, even if involved in legally mandated treatment. Qualitative research mirrors this finding. These studies highlight that loss of a voice, Reference Sorgaard30 disrespect by professional staff Reference Olofsson and Norberg31 and violation of integrity Reference Olofessen and Jacobsson32 lead to feelings of coercion. These papers are interesting as they do not focus on a particular intervention, rather the patients' experience. It would seem as if the experience of coercion is at least as related to the interpersonal experience of the patient in their relationship with those delivering care rather as it is to particular psychiatric interventions.

Do ‘coercive interventions’ work?

If the experience of coercion is common, as it appears to be, and we are unable to reliably assess who is most coerced, positive outcomes become the justification for compulsory actions leading to coercion. These outcome data are, unfortunately, scarce and too heterogeneous to combine in any meaningful way.

The authors of the two randomised controlled trials of community treatment orders, both in the USA, suggest such interventions, clearly associated with coercion, improve outcomes in multiple domains Reference Swartz, Wagner, Swanson, Hiday and Burns18,Reference Haglund, Von Knorring and Von Essen33-Reference Rain, Steadman and Robbins35 although a comprehensive Cochrane review of essentially the same data was less optimistic. Reference Steadman, Gounis, Dennis, Hopper, Roche and Swartz36 It suggests that these same trials showed little improvement in readmissions, social functioning, mental state or quality of life. From a risk perspective the Cochrane review suggests 238 people would need to be under mandated community treatment to prevent a single arrest - hardly an effective intervention.

It is equally difficult to find evidence that compulsory hospital admission, also associated with coercion, leads to improved outcomes. In a large British sample, followed for 12 months, Priebe and colleagues did not find any relationship between outcomes and coercion, although satisfaction with the admission process did appear to be predictive of readmission. Reference Swartz, Swanson, Wagner, Burns, Hiday and Borum37 This finding mirrors the quantitative and qualitative findings of the importance of the interpersonal experience during compulsory interventions.

Implications and limitations

What does all this mean? From a sociopolitical perspective, interventions that increase coercion such as court-mandated treatment appear to be becoming more prevalent despite philosophical and ethical concerns and a lack of evidence that support their use. Major structural change to psychiatric care without any evidence to support its implementation is, unfortunately, not uncommon. Reference Kisley, Campbell and Preston38 Nor does it seem likely that interventions such as mandated community treatments and detention in hospital will disappear overnight. From a pragmatic perspective the question is then how to practice and research psychiatry within the current social and legal framework.

The evidence to date emphasises the importance of the attitudes of mental health workers towards their patients as a key factor that may be amenable to change. A combination of listening and respecting the patient's view is likely to minimise any experience of coercion, even if the outcome is compulsory treatment. Although mental health professionals have worked hard to minimise the negative attitudes towards mental health in the community, Reference Priebe, Katasakou, Amos, Leese, Morriss and Rose39,Reference Malone, Marriott, Newton-Howes, Simmonds and Tyrer40 these negative attitudes remain present even within services, Reference Crisp, Cowan and Hart41 suggesting a need to remain focused on the interactions of all clinicians. The importance of this approach is supported by the work of the MacArthur Foundation who coined the phrase ‘procedural justice’ 42 to express a similar view. For inpatients, the fact that one in four voluntary patients experience coercion suggests consideration of the consent process for intervention in hospital needs to be reviewed, and implied consent in this patient group may not be sufficient. The clear correlation between legal compulsion and coercion, without comparable evidence of improved outcome (or improved community safety) would recommend any course of action that reduces compulsory status as beneficial to individual patients.

The key factors for psychiatric practice when considering coercion include the following:

-

• the philosophical and ethic basis for compulsory treatments leading to coercion is the improved freedoms to the patient and beneficence;

-

• half of all in-patients experience coercion and the rates are probably similar in the community;

-

• consent to voluntary admission to hospital does not imply consent to all procedures in hospital;

-

• legal detention increases coercion with mixed evidence of it improving outcomes;

-

• there is very limited evidence that legally mandated community treatment improves patient outcomes or the safety of the public.

On a broader scale the need to continue to understand coercion, separate from compulsory actions, remains important and peer-reviewed tools are available to improve the methodological robustness of research. Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer and Weaver43 The social impact of coercion needs to be considered by public policy and law makers to ensure interventions are not developed that work against the destigmatisation of mental health and do not further alienate a vulnerable group of people. When potentially coercive cultural interventions are implemented, examination of their impact is essential.

Finally, all mental health workers need to bear in mind the difficulties struggling with a mental illness can bring and be reflective about how they can work with individuals to maximise the chances of a positive outcome from a patient perspective, and to this end minimise the threat of coercion in day-to-day care.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.