The clinical dashboard is a tool set of visual displays developed to provide clinicians with the relevant and timely information they need to inform daily decisions that improve the quality of patient care. It enables easy access to multiple sources of data being captured locally, in a visual, concise and usable format.

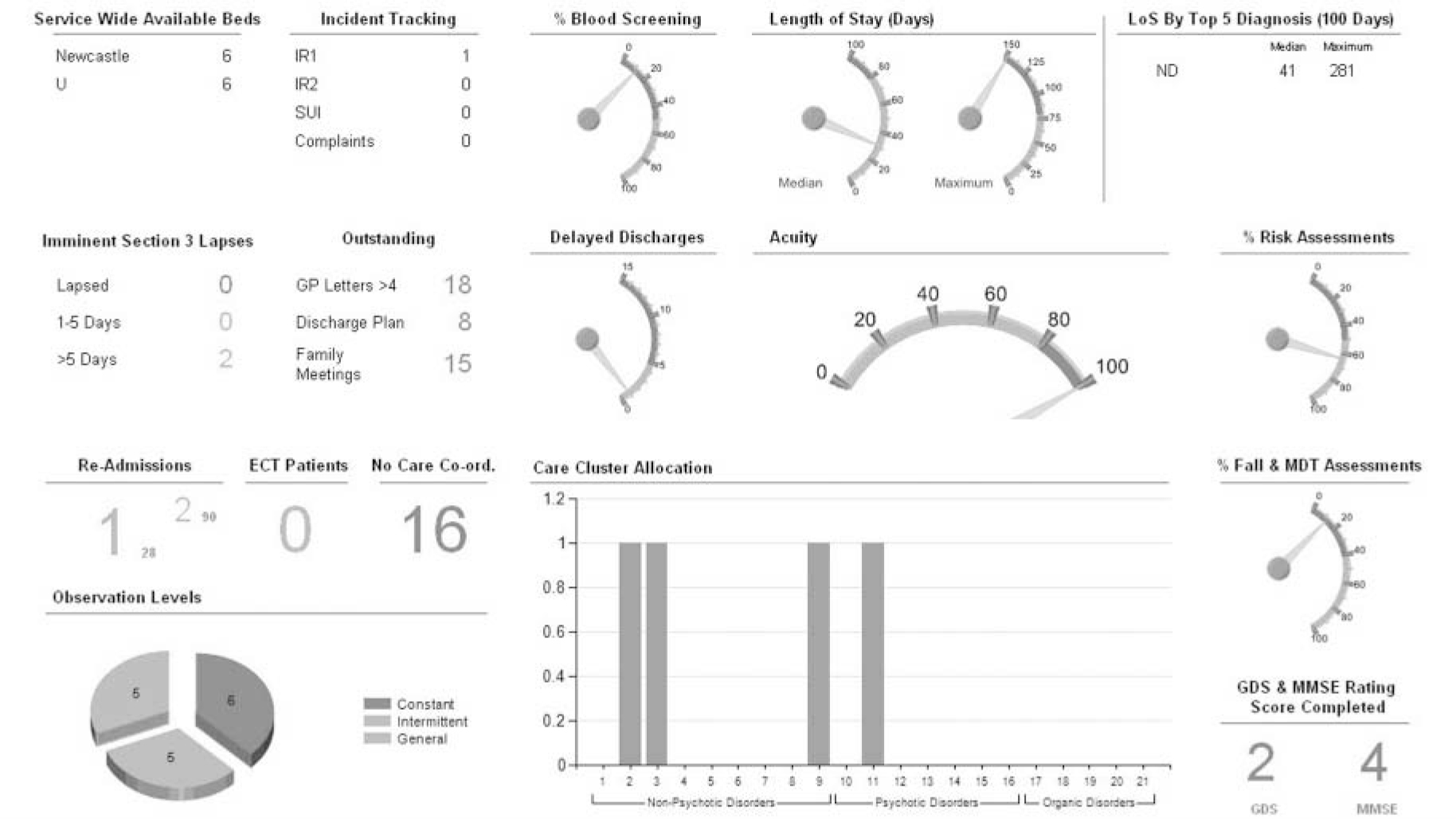

The development of the dashboard was a key recommendation from Lord Darzi’s Next Stage Review. 1 Its aim is to enable clinical teams to identify and track key areas of their daily work to facilitate improvements in efficiency, effectiveness and most importantly, to improve overall quality of patient care. It pulls together existing electronic information into a visual format, using innovative technology to help clinicians make well-informed, timely decisions (Fig. 1). Some examples of the type of information covered by the dashboard include bed occupancy, length of stay, number of completed assessments and number of incidents. 1

Fig 1 The in-patient clinical dashboard.

A number of papers have been published looking at the implementation of electronic patient records and the impact this has on individuals and services. Reference Greenhalgh, Stramer, Bratan, Byrne, Russell and Potts2,Reference Greenhalgh, Wood, Bratan, Stramer and Hinder3 The UK government has also released a White Paper for consultation on the use of information, which will have a major impact on how we use information within health services. The Department of Health hailed it ‘the information revolution’ that is ‘part of the Government’s agenda to create a revolution for patients - “putting patients first” - giving people more information and control and greater choice about their care. The information revolution is about transforming the way information is accessed, collected, analysed and used so that people are at the heart of health and adult social care services’. 4

Previous studies looking at staff perceptions of electronic patient records in mental health have highlighted a number of difficulties; still, findings suggest that clinicians do not want to go back to paper records. Reference Mistry and Sauer5 To date, there have been no studies published which evaluate the dashboard concept in an older persons mental health service.

Following the success of the first clinical dashboard prototypes, NHS Connecting for Health established a pilot clinical dashboard programme, aiming to extend the dashboard across the 12 strategic health authorities, covering a range of clinical specialties. Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust were one of the 12 pilot sites, and the only mental health trust involved in the pilot. 6 Within the Trust, the dashboard was implemented in three old age psychiatry multidisciplinary services: in-patient wards, a community mental health team and the memory assessment and management service.

The aim of this study was to explore staff perceptions relating to the introduction and use of the clinical dashboard following its implementation within old age psychiatric services in one National Health Service (NHS) mental health trust. Specifically, the study focused on the assessment of any benefits, the difficulties encountered and potential value of the tool in a mental health setting.

Method

A questionnaire was developed to obtain hard statistical data, comprising a series of closed questions to promote better data analysis (see online supplement to this paper). Reference Boynton7 Open questions were also included to enable respondents to relay their individual thoughts and feelings on specific issues.

To encourage questionnaire completion and facilitation of an open and honest response, the questionnaire was anonymised. It asked staff about their experiences of using the dashboard, both in terms of the benefits and difficulties encountered, and called for suggestions for how it could be improved. To gauge the opinions of as many disciplines as possible, the questionnaire was given to staff working within the pilot sites to complete over a 1-week period. The sampling technique targeted team meetings.

Results

During the sample period there were 40 permanent staff working in the pilot areas and these were targeted by the study. They had been trained to use the dashboard. After 1 week, 24 questionnaires were returned (a 60% response rate), of which 3 were incomplete and excluded from further analysis. The 21 completed responses came from the community mental health team (n = 12), the memory service (n = 2) and the in-patient unit (n = 7). The respondents were: 8 qualified nurses, 6 medical staff, 6 allied health professionals, and 1 administrative and clerical staff. Those who returned their questionnaires incomplete felt that they had insufficient experience with the dashboard to comment, which may have been due to the fact that the survey took place only 3 months after implementation.

All dichotomous data were coded and all qualitative data were accessed thematically. Responses judged to be within the same theme were summed (the judgements were made collaboratively by K.D. and J.R.).

Of the completed questionnaires, 8 people (38%) reported to have found the dashboard helpful thus far; 15 (71%) found it easy to use, and 18 (86%) thought the format was easy to understand. Of those who responded, 15 (71%) were able to cite at least one benefit they had derived from the dashboard (Table 1) and 11 (52%) cited at least one difficulty (Table 2).

Table 1 The most commonly cited benefits of the clinical dashboard

| Benefits | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Timely access to information | 13 (62) |

| Increased communication and information-sharing | 10 (48) |

| Increased staff awareness of information | 9 (43) |

| Data quality | 7 (33) |

Table 2 Difficulties experienced with the clinical dashboard

| Difficulties | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Accessing the dashboard | 11 (52) |

| Service disruption | 4 (19) |

| Duplication of information | 2 (10) |

In terms of the content of the dashboard, 48% of respondents (n = 10) perceived the current metrics to be useful. The metrics were locally defined and dependent on data that were available electronically within the organisation at that point in time. Additional metrics that staff proposed as useful to include were:

-

• waiting times

-

• number of patients on antipsychotics/date medication last reviewed

-

• number of patients on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

-

• percentage of clinicians adherent to National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance for dementia

-

• number of patients with their payment by results mental health cluster completed

-

• patient satisfaction.

Two members of staff suggested that the current metrics were more useful for managers and audit purposes, noting that the above additions would make the dashboard more pertinent to clinicians.

Suggestions were also given on how to improve the dashboard system overall:

-

• to include more multidisciplinary team meeting information within the dashboard

-

• to make it more clinically oriented

-

• to improve access to live system and investigate any technical difficulties

-

• to look into using the dashboard with patients and/or relatives (57% of people felt that patients/relatives would find this helpful)

-

• to draw on the experiences of successful implementation sites to enable the dashboard to become successfully embedded into all services.

No additional comments or suggestions were made outside of the above.

Discussion

This study explored staff perceptions of the clinical dashboard 3 months after it had been introduced. The dashboard was shown to have been successfully implemented in this setting; it was received well by the majority of staff, and the early benefits were evidenced.

A number of quantitative measures have also been tracked which also support the staff’s perceptions. In addition to improving access to information and increasing communication, the recording, on the Trust’s electronic patient record, of two of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Accreditation for Inpatient Mental Health Services - Older People (AIMS-OP) metrics improved: a recorded multidisciplinary team meeting and recorded falls assessment.

The AIMS-OP is an accredited system for standards of care within an older persons mental health ward. The numbers of recorded multidisciplinary team meetings increased from 54% at baseline to 94% at 6 months. The numbers of recorded falls assessments increased from 0% completed at baseline to 82% at 6 months.

The dashboards were reviewed in the team handover meetings, with detailed drill-down facilities being used to access the underlying information that was available and to provide support for continual improvement.

Despite the benefits of the dashboard, there were some difficulties encountered, namely staff access, inaccurate data and increased workload. It is suggested that to some extent these difficulties are a reflection of the piloting process; nevertheless, they should not be discounted. As the dashboard was rolled out, it brought together data that had not been previously used by staff, and as a result highlighted data gaps. This resulted in an initial increase in workload, as the data required to support the metrics identified had to be gathered and entered into the electronic patient record within the Trust. It is envisaged that as the dashboard becomes more embedded in services, and the use of electronic systems becomes routine, these issues will reduce, and the process will become less labour intensive and data more accurate.

Within the study, changes to the dashboard’s content (e.g. the metrics) were also suggested by staff. Even as the local teams were defining the first metrics, there was a recognition that the dashboard would need to evolve in line with experiences of what works, what does not work and changing needs over time. This feedback will be a key driver for future development and refining of the dashboard system, ensuring it is more relevant to clinicians and responsive to local needs.

Limitations and further comments

One key limitation of this study was the response rate. This may reflect the nature of the sampling technique which targeted team meetings and which occurred over a 1-week period. Many staff felt unable to comment on the dashboard owing to limited experience, which is possibly due to the stage at which the study was carried out.

It would be useful to revisit this again in 12 months, when the dashboard has become more embedded into services. A further evaluation of whether the benefits brought by the system outweigh the perceived costs and whether these were linked to a sustained increase in quality of care would be useful.

What became evident even at the pilot stage is that the clinical dashboard is able to support quality improvement programmes, such as the AIMS-OP from the Royal College of Psychiatrists. It enables problem areas to be identified and tracked, which could in turn improve service efficiency and overall quality of care.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.