Introduction

What makes a job candidate in the food service industry the right fit? This paper examines the generative process through which schema of candidate appropriateness in an important low-wage and nominally low-skill industry is constructed. Our qualitative research examines the extent to which race, country of origin, immigration status, and gender inform employment decisions. What we ask is two-fold: (a) What makes a worker the right ‘fit’ in the food service industry? and (b) to what extent is this ideal a gendered, racialised, and status-oriented construct? Our intersectional qualitative analysis reveals that employment opportunities and outcomes are conditioned by converging factors, such as gender, race and citizenship status (see Collins Reference Collins2019). Broader forces of socialisation that might stream gendered and racialised applicants into particular roles, along with employer discrimination, play a role in shaping these outcomes. This, we argue, is part of the structural conditions of racism and sexism expressed at the hiring stage that are produced within a particular socio-economic milieu; simple organisational responses that hinge upon convenient equity, diversity, and inclusivity (EDI) narratives are inadequate when attempting explain how labour market opportunities and systems of marginalisation arise. Established labour market data illustrate this point by measure of unemployment and participation rates, as well as the share of food service workers broken down by gender and race (Statistics Canada 2022b, 2023a, 2023d). High unemployment rates for Indigenous workers in Canada, and widely divergent unemployment rates across ethnicity and race, illustrate the importance of this line of inquiry (Statistics Canada 2023b, 2023c).Footnote 1 This study further asks, to what extent might discrimination in the recruitment process contribute to racialised and gendered employment outcomes in the food service industry?

What makes this line of inquiry significant is the fact that food service work is widely considered to be a training ground for future employment, wherein entry-level jobs provide future opportunities (Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association 2010). An inability to secure work in this and otherwise lower-skilled ‘entry’ type service positions could affect short- and long-term employment prospects, compounding existing labour market inequalities. But labour market discrimination is not experienced uniformly across race and citizenship status (Hum and Simpson Reference Hum and Simpson2000), indicating that biases resulting in discrimination against ethnicities or newcomers from certain countries are contextual. This industry is also important to study because of its problematic work-life balance, high levels of stress, long hours, and shift schedules that dissuade younger workers from making a career in food services (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, McAdams, Gibbs and D’Angelo2022). A young worker’s experiences in their first job affect their attitudes and beliefs for the rest of their career (Loughlin and Barling Reference Loughlin and Barling2001).

The study looks at the attitudes held by food service employers and workers, because of the important role they play in shaping the experiences of employees and job applicants, and their respective roles in generating the mechanisms of exclusion and opportunity otherwise known as ‘fit’. Interview coding allowed us to refine this mechanism further and uncovered that managers prioritise a perceived willingness to work in a precarious employment setting, cultural competencies, communication skills, personal networks that supersede established credentials and experience, and customer service aptitude. Fit, we find, helps us to advance an understanding of industry-specific divisions of labour defined by income and occupational outcomes. For women, a gendered construction of fit might provide some specific employment opportunities, whereas for Indigenous job seekers, an employer’s explicit or unconscious biases produce and reproduce obstacles to securing work. But while racism ‘circulates through individual attitudes and behaviours, sometimes unconsciously’, its origin and capacity to be sustained and reproduced requires a structural explanation (Kundnani Reference Kundnani2023, 4). Socially constructed notions of fit might also uncover opportunities for certain ethnicities who are perceived as inherently hard-working. All are outcomes of constructed ‘soft skill’ requirements deployed by food service employers. Our analysis of interviews gives shape to these conclusions.

Accounts generated from interviews with frontline workers and managers assist in establishing findings that help to understand how employment exclusion and opportunity manifest through a process of generating fit. Such a form of structural discrimination is maintained by the vetting of applicants and potential employees, resulting in the creation of a precarious, ‘ideal’ workforce based on gender, race, country of origin, and immigration status.

Literature review

There are inherent difficulties in measuring hiring discrimination, because employers are unlikely to admit to this form of exclusion, and more objective data, such as wage inequality figures, fail to establish causality between demographic characteristics and uneven labour market outcomes. Unfortunately, anti-discrimination legislation, by itself, is not enough to prevent this exercise of exclusion or to mitigate the effects of existing practices and biases that might be perpetuated within organisations despite these important policy advances (Beattie and Johnson Reference Beattie and Johnson2012). Similar conclusions can be drawn about EDI initiatives within organisations. Our study characterises how labour market opportunities and disadvantages are created through the production of what constitutes a fit employee through a process that involves challenging assumptions that connect educational attainment and credentials with social and economic mobility (Lang and Manove Reference Lang and Manove2011; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2004). Human capital theory, for instance, suggests that educational advancement, networking, labour market experience, and the search for new sources of employment enable economic success (Becker Reference Becker1964). Poverty and poor economic outcomes can be eliminated, according to this account, by investments into appropriate education and training as self-interested actors pursue objectives in a self-equilibrating labour market (Marsden Reference Marsden1986). And where classic human capital theories account for the effects of discrimination and prejudice on economic outcomes (Becker Reference Becker1957), our study extends that analysis by examining the utility of fit in manufacturing an ideal food service worker. The neo-liberal economic theories advanced by Becker, and others are themselves rooted in racist discourses that situate achievement prospects on the backs of individuals, and where the biases of employers can be mitigated through education and knowledge attainment (Kundnani Reference Kundnani2023). Labour segmentation theory assists in countering the assumptions rooted in human capital models of employment attainment.

The segmentation model maintains that labour markets are complex, and institutional structures and social spaces are divided into submarkets with different sets of rules governing the behaviour of labour market actors within (Michon Reference Michon and Tarling1987). First-generation segmentation theories hold that certain groups are excluded from internal labour markets, thus creating ‘balkanised’ labour markets (Dunlop Reference Dunlop1964) constituted by primary and secondary sectors. Vulnerable workers can become trapped in lower segments of the market due to institutional barriers that prohibit certain demographics from benefitting equally from education and human capital attributes (Leontaridi Reference Leontaridi1998). Researchers on immigrant economic integration find that foreign credentials and experiences might work against job seekers, negatively affecting their labour market or upward mobility (Ertorer et al Reference Ertorer, Long, Fellin and Esses2022).

In the second-generation segmentation theory, the literature suggests that workers develop traits that deem them unsuitable for primary sector employment, thus reaffirming the social nature of labour power (Peck Reference Peck, Stephen Ackroyd and Fleetwood2000). This dualist model tends to focus on the characteristics of the jobs themselves, not just workers. Streaming into one or another sector might be conditioned by demographic variables such as sex or status – enabling the economic marginalisation of women and newcomers for example – which then constructs and maintains gendered or status-based divisions of labour. These forms of segmentation might also exist within primary or secondary sectors, or even within particular organisations (Bernard-Oettel et al Reference Bernard-Oettel, Leineweber and Westerlun2019). Employer acceptance grants entry into primary labour markets, while discrimination diverts workers into secondary markets. Cultural attributes, Bauder (Reference Bauder2001) suggests, also plays a role in constructing desirability (or marginalisation) in the eyes of capital. This aligns with Willis’ (Reference Willis1981) canonical examination of how working-class cultures are developed.

‘Third-generation’ segmentation models build upon this understanding, wherein social forces play a central determining role in forming the structure and organisation of employment (Peck Reference Peck, Stephen Ackroyd and Fleetwood2000). Divisions between economic and institutional structures are eroded in this political-economical system shaped by state-labour relations. Migrants, for instance, are streamed into particular sectors that are commonly defined by a level of precarious work that matches their precarious status in hierarchically defined employment relations (Adham Reference Adham2023). National migration schemes facilitate this segmentation (Almeida and Fernando Reference Almeida and Fernando2017). Globalisation is such that foreign-born labour might be overrepresented in the least desirable labour market positions (Lusis and Bauder Reference Lusis and Bauder2010), pooled collectively in ‘3D’ employment: dirty, dangerous, and degrading (Stalker Reference Stalker2000). Migrants are then relied upon to fill labour market shortages caused by expansive opportunities for local workers in primary sectors (Piore Reference Piore1979). Research also suggests that women receive lower returns from human capital investments, like education and experience than men, which contributes to ongoing pay inequities and their respective diversion into secondary markets or occupations (Peetz Reference Peetz, Peetz and Murray2017). This approach accounts for how workers with similar levels of productivity are paid differently because of diminished bargaining power emerging from socio-economic factors.

The stereotype content model crafted by Fiske et al (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002, 899) helps to recognise qualitative differences in stereotypes and prejudices, whereby biases can create advantages and disadvantages along intersectional axes of class, race, sexuality, gender, age, employment status, among other demographic factors. This aligns with Patricia Hill Collins’ (Reference Collins2019, 37) assertion that intersecting ‘power relations produce social divisions of race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, age, country of origin, and citizenship status are unlikely to be adequately understood in isolation from one another’. Seemingly innocuous soft skill requirements in this regard can function to discriminate against people of colour, individuals from lower economic positions, people with disabilities, and other groups that fail to measure up to an idealised appearance (Canton et al Reference Canton, Hedley and Spoor2022; Durante et al Reference Durante, Tablante and Fiske2017; Lindsay et al Reference Lindsay, Adams, Sanford, McDougall, Kingsnorth and Menna-Dack2014). Perceptions of warmth and other stereotypes, like competence, can also be associated with a particular country or origin (Motsi and Park Reference Motsi and Park2020), shaping the attitudes of employers and other workers when making decisions about hiring immigrants in the service industry based on the sending nation (Waldinger Reference Waldinger1997). There is also evidence that resume quality increases the rate of employer callbacks more for whites than racialised minorities, demonstrating the limits of credentials in overcoming structural forms of discrimination (Neumark Reference Neumark2012).

The available research literature on what constitutes fit in the food service industry also merits consideration given the social construction of skill and the associated rewards that accompany these requirements (Steinberg Reference Steinberg1990). Ostensibly low-skill food service jobs are recognised as needing nebulously-defined ‘soft skills’ that extend beyond what is prescribed in formal occupational classification systems. Here, ‘skill’ is influenced by cultural perceptions, social context, and worker characteristics where hiring decisions can be shaped through biases held by employers (Lindsay et al Reference Lindsay, Adams, Sanford, McDougall, Kingsnorth and Menna-Dack2014). In some instances, the legitimate need for specific qualifications and experiences (i.e., effective communication skills) might be difficult to discern from those premised on implicit prejudices held by employers (Almeida and Fernando Reference Almeida and Fernando2017). For Zamudio and Lichter (Reference Zamudio and Lichter2008, 577), soft skill requirements can render more sophisticated ‘discriminatory race talk’ as these requirements overshadow the limited formal skills required to perform frontline food service duties. These are emergent features of intersectionally defined socio-economic realities. Some soft skills are then valued or devalued based on the conviction of managers tasked with vetting resumes and applications. Possessing an ability to maintain professionalism under difficult working conditions might be paired with an ability to ‘look good’, emphasising the need to manage emotions and aesthetics, in addition to the limited hard skills curated in the job description (Nickson et al Reference Nickson, Warhurst and Dutton2005). Soft skills, such as managing one’s appearance and attitude, rank highly as desired traits by employers in this industry (Martin and Groves Reference Martin and Groves2002) in the interest of conforming to an employer’s brand image (Williams and Connell Reference Williams and Connell2010).

Building on these findings, researchers in the United States find that qualities identified by employers as to what constitutes a good hire could be construed as racialised code words, such as ‘good attitudes’, ‘work ethic’, ‘drive’, ‘presentable’, among others (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United 2015, 23). Racialised job seekers might then respond to this reality by ‘whitening’ their resumes to avoid projecting a racialised identity (Kang et al Reference Kang, DeCelles, Tilcsik and Jun2016), implying a pattern of resistance against presumed racist attitudes and biases. Interview questions that are consciously or unconsciously discriminatory can also negatively affect the propensity of minority candidates to accept employment if they perceive the organisation itself to exclusionary (Saks and McCarthy Reference Saks and McCarthy2006). This vector of analysis is germane when employers vet resumes for food service positions, as findings from our examination of interviews conclude.

Some employers voice apprehension about hiring foreign-born workers, although it is common in this industry hire low-skilled foreign labour through federal and provincial nominee programmes and temporary foreign worker programmes (Stevens Reference Stevens2022). One ethnic group, for instance, can be idealised for their work ethic and ability to succeed in low-wage, routinised forms of employment, whereas another is deemed to be unreliable (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Lin and Neuberg2018). This form of stereotyping can stem from judgements connected to the embodied cultural capital possessed by newcomers and racialised labour (Bauder Reference Bauder2006). Workers with specific ethnicities might then be streamed into lower- or higher-paid occupations within the industry as a result of these biases (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United 2015) which reflects the function of labour market segmentation. Incomes and mobility are affected as a result. These challenges are particularly acute for Indigenous peoples in Canada, who experience endemic unemployment and poverty rates which are above national and provincial averages. Indigenous peoples also less likely to possess secondary or post-secondary levels of education, along with lower labour market participation rates than other demographics (Government of Saskatchewan nd; Layton Reference Layton2023; Stevens and Poirier Reference Stevens and Poirier2023).

Precarious work if you can get it

Food service employment is typically precarious labour. In this industry, fit is another means of favouring pliable, non-problematic workers, who look a specific way and who possess particular communication skills (Lindsay et al Reference Lindsay, Adams, Sanford, McDougall, Kingsnorth and Menna-Dack2014). Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu2003, 29) describes precarity as a ‘mode of domination’, while other scholars define this type of work as ‘uncertain, unstable, and insecure’ (Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg2018, 3). The literature also positions precarious employment as being characterised by stress, exhaustion, overwork, anxiety, and ill health, even in skill-intensive knowledge work (Gill Reference Gill2014). Vosko (Reference Vosko and Vosko2006) has further outlined precarity as shaped by employment status, form of employment, occupation, industry, and social location (race, gender). Established research aligns these conditions with the lived realities of work in the food service industry (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, McAdams, Gibbs and D’Angelo2022). Studies of Canada’s migrant labour regime similarly outline foreign workers as occupying an inherently precarious living conditions given the tethering of employment with legal status (Connelly Reference Connelly2023; Woolfson et al Reference Woolfson, Fudge and Thörnqvist2014). Newcomer status merits further analysis in the context of generating an understanding of ‘fit’. Human resource practices in a labour-intensive sector, such as food services, amplify the problem and contribute to turnover and failed recruitment campaigns (Kusluvan et al Reference Kusluvan, Kusluvan, Ilhan and Buyruk2010; Martin and Groves Reference Martin and Groves2002; Park et al Reference Park, Song and Lee2017).

Sexual violence and toxic workplaces further play a role in creating a disenchantment with food service work, especially following a wave of #metoo allegations levied against specific businesses and managers (McAdams and Gordon Reference McAdams and Gordon2021). Businesses, meanwhile, continue to cite fit as an issue, without further elaboration. ‘We’re not struggling to find people’, a Regina-based business owner remarked. ‘We’re just struggling to find the right people’ (Sciarpelletti Reference Sciarpelletti2021). Older, more experienced workers left the industry, meaning that younger employees were relied upon to fill vacancies. Ultimately, employers have made clear that they require an experienced workforce that is willing to work for low pay under worsening circumstances. A failure to provide decent work, some scholars suggest, has exacerbated the problem (McAdams and Gordon Reference McAdams and Gordon2021). COVID offered the precariously employed both an incentive and a window through which to exit the industry as half of unemployed food service workers found employment in other industries during the pandemic (Janzen and Billy-Ochieng Reference Janzen and Billy-Ochieng2021). These findings align with studies showing that hours of work, shift schedules, and work-life balance realities deter prospective workers from wanting to enter the industry (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, McAdams, Gibbs and D’Angelo2022). The right fit, we argue, means a workforce conditioned to labour under these conditions, in what Willis (Reference Willis1981) articulates as the production and reproduction of working-class subjects.

Methods

Between 2021 and 2022, 92 semi-structured interviews were conducted with business owners, employment agency representatives, union representatives, hiring managers, and individuals who had been employed as food service workers (Frontline non-managerial food service workers = 62; Managers and supervisors = 28; union representative = 1; employment agency representative = 1) about hiring practices, working conditions (COVID-specific and general), racial and gendered biases, and discrimination along the axes of Indigeneity, race, immigration status, and gender. We asked managerial and supervisory participants additional questions about hiring foreign labour, newcomers, and prospective Indigenous workers. The semi-structured nature of our interviews allowed follow-up inquiries with participants that allowed for an exploration of additional themes and examples. Interviews were then recorded, transcribed, and coded using NVivo software along five principal themes: discrimination, what constitutes fit, hiring practices, resistance, and stated reasons for hiring. Participant recruitment was facilitated through word of mouth, university email list-servs, personal networks, and cold calls in the provinces of Saskatchewan and Ontario, representing a mix of urban, semi-urban, and rural employees.

Together, these two jurisdictions provide a snapshot of what are broadly Canada-wide issues related to food service employment, a growing reliance on newcomers to compensate for domestic labour market shortages, higher-than-average Indigenous unemployment rates, and the prevalence of women in their respective food service industries. The food services industry was also chosen with care; low-skill food service occupations such as servers and line cooks dominate job postings, yet receive the lowest number of applications across Canada and the United States (see also 7shifts 2021; Bouchard Reference Bouchard2021; Statistics Canada 2022c).

Our study uses a grounded theory generative approach to analyse interview data. Specifically, we employ the Gioia Methodology (GM) (Magnani and Gioia Reference Magnani and Gioia2023) to construct a qualitative, evidence-based narrative and an aggregate understanding of participant statement using first-order quotations and second-order themes (Gioia et al Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). GM was crafted in the late 1980s as response to a critique of research models by quantitative scholars who questioned the rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative analysis (Corley and Gioia Reference Corley and Gioia2011; Gioia Reference Gioia2021; Gioia et al Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Constructionist epistemologies emphasise the inductive nature of theory building by unpacking the socially constructed nature of reality (Berger and Luckmann Reference Berger and Luckmann1967); human agents therefore engage with the creation of social structures and, in turn, empower or hinder actions by these very same agents. Coding followed an iterative process informed by multiple researchers who constructed codes and associated meanings. GM was then applied to this rendering of worker and manager understandings of the intersections of race, gender, status, and class when determining the fit criteria creating possibilities for securing work in the food service industry. For GM scholars, ‘in our way of thinking, concepts are precursors to constructs in making sense of organisational world’ (Gioia et al Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013, 15); direct engagement with interview findings provides richness to the process, as well as helping to explain phenomena under investigation.

Interview demographics

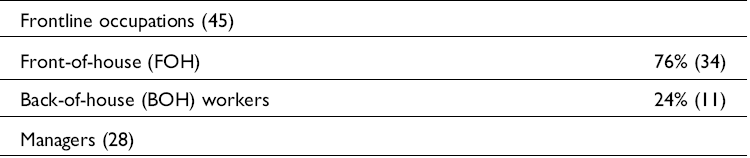

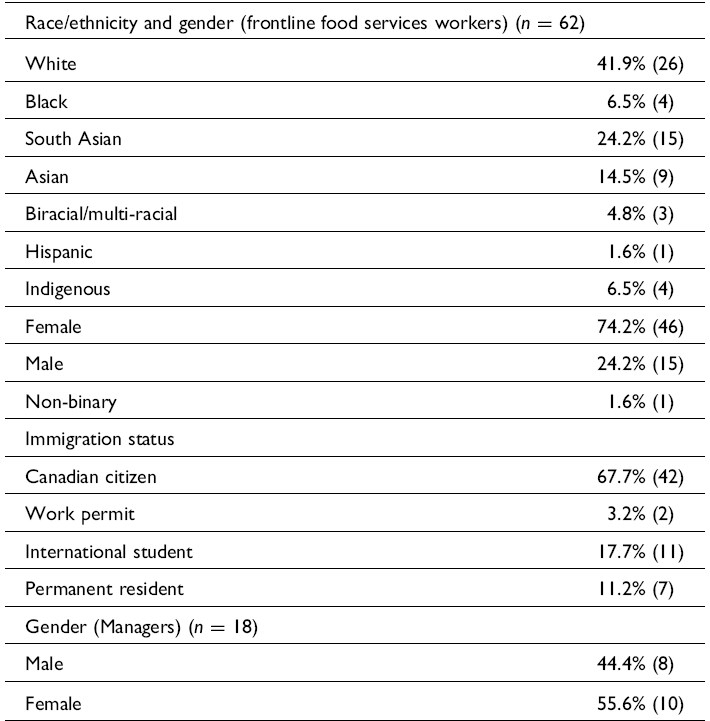

Most of the interview participants who provided occupational information identified as front-of-house (FOH) workers who are customer-facing, like servers and bar tenders; 24% of frontline participants are back-of-house (BOH) and employed in occupations such as cook or dishwasher (see Table 1). Participants were representative of the food service workforce: young, white, and female (see Table 2). The average age of interview participants was 25.5 years (SK = 25.8, ON = 25.2), and most were women (74.2%). This is consistent with the food service and accommodation labour force across Canada: 56.4% of those with income who work in this sector are female (ON = 56.4%, SK = 58.2%), and in Canada, 61.5% of the industry are not visible minorities (ON = 56.6%; SK = 58.1%) (Statistics Canada 2022a; data obtained by special request and calculations performed by research team).

Table 1. Interview participant occupations

***The percentages and numbers are representative of the interview participants who divulged occupational and demographic information. In total, there were 93 interview participants. FOH occupations include bartenders, servers, hosts, supervisors, servers, and baristas. Some of these occupations might occupy more than one role, such as supervisors who also hold server positions. BOH occupations include cooks and dishwashers. Managers might serve and provide frontline servers, but their principal role is managerial in nature.

Table 2. Interview participant demographics

***The percentages and numbers are representative of the interview participants who divulged occupational and demographic information. In total, there were 93 interview participants. ‘Frontline’ food service workers include FOH and BOH non-managerial occupations.

How businesses manufacture ‘fit’

Fit at first emerges in our interview analysis as a common sense understanding of the ideal food service worker: competent, hard-working, and flexible, all of which are requirements that have appeared in industry-focused literature attentive to human resource practices (Warhurst and Nickson Reference Warhurst and Nickson2007). And like soft skill requirements, fit is notably subjective and linked in the research to employer discrimination against particular races and ethnicities (Zamudio and Lichter Reference Zamudio and Lichter2008). As in every industry, expectations and requirements fluctuate across enterprise and occupational classifications. We find that communication skills and personal attributes shape the gendered, racialised, and status-based hiring preferences based on real and perceived notions of what constitutes cultural competency and aptitude for work in this industry (Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich Reference Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich2011; Delgado and Stefancic Reference Delgado and Stefancic2017). Fit is in many ways a performance meant to appeal to employers and customers alike. Our findings also suggest that race and gender do not always affect hiring decisions identically. Put succinctly, ‘not all stereotypes are alike’ (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002, 878). Occupational demands, position within the establishment (i.e., FOH or BOH), and individual biases shape recruitment decision-making. Data also point to racism and race-based discrimination manifesting in the relationships between co-workers, between managers and frontline staff, and between workers and customers (Brewster and Nowak Reference Brewster and Nowak2019). As Stanley (Reference Stanley, Gebhard, McLean and St. Denis2022, 129) insists, a structural explanation of racism ‘departs from common sense views of racism as only involving prejudiced, ignorant or badly intentioned individuals’, with these structures producing negative consequences for those being excluded. ‘Fit’, then, is understood as the characteristics associated with the ideal candidate, capable of enduring precarious working conditions that involves a form of exploitation and discrimination (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, McAdams, Gibbs and D’Angelo2022). More than work experience and other credentials, employers appear to seek nebulous qualities that invite exclusion (or invitation) based on what biases determine the appropriate fit.

Findings from our study conclude that resume credentials can be undermined by less definitive and highly subjective cultural attributes and social networks that are sought after by employers in their review of job applications. ‘Whiteness’, scholars argue, can be expressed as a dominant social norm that constructs particular racial attributes as either ideal or pejorative (McLean Reference McLean, Gebhard, McLean and St. Denis2022) – or, as Dar et al. (Reference Dar, Helena, Martinez Dy and Brewis2021, 696) advance, a ‘regime of power that normalises white dominance’. Who is considered a ‘legitimate’ candidate in the food service industry is both gendered and racialised (Mirchandani Reference Mirchandani2003). A willingness to conform to low wages, uncertain schedules, and otherwise precarious circumstances populates the list of characteristics that define the ideal food service worker, which aligns with research on why migrant workers constitute an ‘ideal’ work force in Canada (Polanco Reference Polanco, Choudry and Smith2016). Fit, one interviewee insisted, transcends sex and race in a tight labour market where good workers are seen as difficult to attract and retain. Work ethic is more important than anything for one ten-year food service industry veteran, who stated simply: ‘If you’re the right fit, you’re the right fit’ (SK Hiring Manager 6). Frontline workers and employers shared this perspective, adding that this specification existed along an intersectional axis. Racialised workers might be hired, but only for BOH duties.

I just know because a lot of the front of house, it’s not multicultural at all, but the back of house is. You have a bunch of different races and stuff. They’re all amazing, great, I don’t know, I know there’s a couple people who wanted to be servers and weren’t allowed to. (SK Frontline Worker 11)

Managers made it clear that good employers face fewer challenges when looking for good workers. This speaks to the value of reputation, of providing a good working environment, and offering entry-level positions close to what might be considered a living wage at the time of the interview. Job interviews were conducted with the intent of securing an understanding of the applicant’s personality, and whether or not they could work successfully in a team. Employers privileged face-to-face introductory meetings and interviews for the same reason (Martin and Groves Reference Martin and Groves2002). However, that preference also positioned employers to ascertain fit and cultural affinity during the hiring process, introducing another vector of exclusion. Or, as one food service worker put it, an opportunity to wield ‘pretty privilege’.

‘Pretty privilege’ and the appeal of aesthetic labour

Labour force data make clear that women are overrepresented yet underpaid compared to men in the food service industry (Statistics Canada 2021). Gendered traits, research finds, provide female applicants with advantages in securing employment in this industry due to traits that employers deem as desirable (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002). However, women are also likely to suffer from wage inequity due to the very stereotypes and occupational segregation that provide these advantages (Cave and Kilic Reference Cave and Kilic2010; Skalpe Reference Skalpe2007; Zhong et al Reference Zhong, Couch and Blum2011). ‘Sexy women’, as a subgroup, has appeared in previous research as being recognised as ‘warm’ and thus possessing certain competencies in particular circumstances (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002, 898). Our findings suggest that employer biases towards particular physical characteristics and other social attributes as affecting hiring decisions more than the experiences outlined in resumes, women who are deemed attractive by male managers are seen as sexual subjects that render advantages to the business that hires them (Warhurst and Nickson Reference Warhurst and Nickson2007). Sexualisation, interviewees suggest, is normalised. The same can be said about race as a determinant of being considered for a position in food services.

Frontline workers generally assumed that women have a better chance of being hired for FOH positions because they are perceived as being more polite, organised, and provide better customer service (Hochschild Reference Hochschild1983) in a sexualised and segmented intra-industry labour market (Bernard-Oettel et al Reference Bernard-Oettel, Leineweber and Westerlun2019). For Mirchandani (Reference Mirchandani2003) and their work on small-business owners in Canada, emotional labour also possesses a racialised dimension, emphasising the importance of an intersectional lens when unpacking the lived realities of service sector employment. More recent literature has drawn parallel conclusions about the intersectional sociality of affective labour in the hospitality industry as a whole (Farrugia et al Reference Farrugia, Coffey, Threadgold, Adkins, Gill, Sharp and Cook2022). Labour market data demonstrate the industry’s preference for women, but why? Interviewees maintained that attractive servers bring in more customers in full-service restaurants, leading one participant to label this trend ‘pretty privilege’ (SK Food Worker 11) – a particular aesthetic that is both managed and commodified. In the service industry, ‘bodies become the target of discipline’ (Oluyadi and Dai Reference Oluyadi and Dai2022, 714) and uphold the image of what embodiment of what fit must look like. An interviewee’s recollection of a restaurant owner’s comments about female employees is telling: ‘If you don’t feel like you should be Instagram ready, like taking an Instagram picture, then you shouldn’t come to work’ (SK Food Worker 14). Additional personal expenses came with these expectations, as a food service worker in Ontario recalled: ‘It sounds so silly, but it was like an expense of working (at the restaurant), I would get my nails done all the time’ (ON Food Worker 16).

Men, on the other hand, are seen as less friendly, less nurturing, less patient, and less physically attractive, and thus less likely to be hired for FOH server positions (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United 2015). This has a consequence for earning potential and advancement potential (Labour Force Survey 2022). But BOH working conditions are also defined by masculinity and the sexism that permeate male-dominated workplaces (Connell Reference Connell1987; Sachs et al Reference Sachs, Allen, Terman, Hayden and Hatcher2014). When asked why men typically occupy these roles, and women do not, one interviewee remarked, ‘I think when you have a kitchen staff that is mostly male, for the two female kitchen staff we had, I think that there was definitely some probably-not-great workplace environment situations in the BOH, which I think would probably maybe deter if any females wanted to work in the kitchen, just because it is so male-dominated’ (SK Food Worker 15). The distribution of men and women across BOH and FOH food service occupations aligns with these interview findings (Loyser Reference Loyser2018). Physical capabilities and limitations associated with a worker’s sex also condition what employers conceive as a natural division of labour in the workplace – part of what scholars have labelled hegemonic masculinity (Moreo et al Reference Moreo, Pan, Cain, Kitterlin-Lynch and Williams2022). Processes of socialisation and the gendering of particular occupations is as much a consideration here as explicit forms of discrimination. ‘I think experience for sure, first would be the experience, and the second would be – it depends, like if the position requires lifting or if it requires a lot of manual work, they would prefer hiring a guy, and if it’s light work, I think it’s going to be female’, said one Ontario food service worker (ON Food Worker 19).

While managers interviewed for the study were split on their gendered hiring preferences, employment outcomes suggest that women experience an advantage when looking for work in food services (Douwere and Lu Reference Douwere and Lu2021). But this was not without some contradiction and a poignant caveat: depending on the type of restaurant and clientele, gender diversity (i.e., men working in the establishment alongside women) helps to maintain a safe workplace, particularly if customers are seen as a challenge, according to hiring managers. ‘If you’re working at a super rowdy bar or maybe a club’, said a hiring manager in a response to a question about why they might prefer certain genders, ‘it’s… always nice to have a … large male present in certain scenarios and just for safety reasons’ (SK Hiring Manager 10). This manner of paternalism might steer hiring decisions under certain industry conditions. Managers’ preferences hinged on assumptions that women are more competent with multi-tasking – a soft skillset that is required in table service restaurants (Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association 2010; Lindsay et al Reference Lindsay, Adams, Sanford, McDougall, Kingsnorth and Menna-Dack2014; Restaurants Canada 2021). These conventions work to shape managers’ biases that are reflected in hiring decision and thus shape the gendered wage gap that permeates the industry.

Some participants concluded that these hiring decisions affect pay, as servers typically make more money due to tips than BOH workers – managerial roles excluded. Others offered contradictory statements. Men, this group of respondents argue, are more likely to secure BOH positions that receive higher rates of pay, such as supervisory roles, and that males are taken more seriously in the workplace. ‘They are hiring for management positions, they are hiring men’, said one manager (SK Manager 8). And, as one frontline food service worker commented, ‘I would say if a restaurant is looking for servers, ideally they’re probably looking for females’ due to the industry’s preference for attractive workers (SK Food Worker 13). Sexism – or rather, sexualisation – played a role in these hiring and staffing decisions (Kübler et al Reference Kübler, Schmid and Stüber2018; Petersen and Togstad Reference Petersen and Togstad2006). Not only are hiring decisions informed by gendered assumptions and sexual inequality but so too are the experiences of women employed in food services.

Examples of discrimination featured prominently in interviews with food service workers in both provinces. These actions were intersected along racial, status, sexual identity, and gender lines. Sexual harassment, in particular, was referenced at length by participants. Dealing with this lived reality prompted some interviewees to rationalise decisions to exit the industry altogether – particularly when COVID rendered these workers unemployed due to pandemic restrictions. High-profile incidents related to an emergent #metoo movement were referenced at length by Saskatchewan frontline workers (Latimer Reference Latimer2020). Sexism and sexual stereotypes permeated both the hiring practices observed by supervisors and managers, as well as the day-to-day work experiences, leading some researchers to conclude that a combination of individual employers and industry culture ‘create an environment which can encourage inappropriate attitudes, crude language, and egregious behaviour’ (Moreo et al Reference Moreo, Pan, Cain, Kitterlin-Lynch and Williams2022). The notion of hegemonic masculinity helps to explain the normalisation of gender inequality and male dominance over women in the employment setting (Connell Reference Connell1987, Reference Connell2005). ‘Pretty privilege’ might provide an advantage when seeking employment, but it comes with a cost. ‘You have an advantage for being a girl’, said one interview participant, ‘but then there is that disadvantage that you’re always being objectified no matter what you do, and threatened with “There goes your tip”’ (SK Food Worker 12).

When race doesn’t fit

Race and racial stereotypes similarly generate contradictory outcomes in food services. That the industry is the site of nearly a quarter of all workplace discrimination human rights cases in Canada’s most populated province between 2014 and 2022 is telling in this regard (Ontario Human Rights Commission 2022).Footnote 2 Labour market data do make clear that race and ethnicity condition employment and income outcomes. Interview responses account for why. ‘If you don’t look a specific way, you don’t get promoted into the lounge’, (SK Food Worker 14) as one worker said about racism that permeates the industry. This is of significance for racialised newcomers and Indigenous workers. Part of these opportunities and experiences of marginalisation are prefigured by biases that are constructed by employers and rank-and-file workers about the perceived competencies of these demographics. New and existing workers might be streamed into particular roles according to fit, not accomplished human capital attributes.

Interview participants reflected on the anxiety experienced by racialised applicants, and the reality that resumes submitted by non-white applicants might be discarded without much consideration by employers. Decades of audit studies in numerous national contexts have identified similar outcomes in the resume-vetting process (Bertrand and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004; Oreopoulos and Dechief Reference Oreopoulos and Dechief2012; Riach and Rich Reference Riach and Rich2002). ‘I know actually multiple people who dreaded going to an interview because on paper, their name was, let’s say for instance, Paul Stevenson, it sounds white passing, but they were actually of Indian heritage’, said a food service worker in Saskatchewan (SK Food Worker 12). ‘Resume whitening’ is deployed as a conscious strategy aimed at rendering the applicant more acceptable to employers in response to real or perceived biases, and ultimately to amplify their fit and desirability in the labour market (Kang et al Reference Kang, DeCelles, Tilcsik and Jun2016). Accomplishments or awards that might signal the racial or ethnic identity of an applicant could compromise their chances of securing an interview, even when these credentials boost their human capital potential.

There’s certain awards I receive, like I receive the (scholarship name) Harry Jerome Scholarship; the Black Business Association certificate of achievement. I put those kind of things on my resume so they stand out, but at the same time, it’s also revealing my ethnicity. I wonder if that’s a hindrance sometimes. (ON Food Worker 11)

‘Resume whitening’ also functions as act of subversion aimed at building acceptance and signal fit, like Anglicising a name ‘just to be more accepted’ (ON Food Worker 19), or to make it easier for employers to pronounce. In the context of critical race theory, it can be seen as a means for highlighting important human capital characteristics like experience and credentials, while at the same time concealing resume features that disclose a race or ethnicity that could be deemed undesirable by employers. ‘(My) one friend doesn’t use her real name, she’s Vietnamese and it’s like, Hoi, but she uses Joy because it’s easier for people to read’ (SK Food Worker 27). White and racialised participants reflected on why these and other means of subverting discrimination might be deployed. For neo-liberal economists like Becker (Reference Becker1957), this represents a missed opportunity for employers that overlook the true economic potential of qualified workers – a shortfall that he argues can be overcome with information.

But race might also be mobilised as an asset for employers, where racialised workers are ‘exoticised’ and offered a selling point for the businesses due to their inviting, and attractive difference. Their utility is one of commodification and desirability in the eyes of employers (Bauder Reference Bauder2001), not to empower racial inclusion in the workplace. Indeed, as Kundnani (Reference Kundnani2023) observes, racism can be a profitable enterprise for capitalist regimes. Discrimination itself can be mobilised to service political-economic objectives. Aesthetic labour, Warhurst and Nickson (Reference Warhurst and Nickson2009) argue, is the corporeality of workers that is appropriated for commercial benefit. We recognise this as the racial equivalent of ‘pretty privilege’, where race can function as an advantage in the hiring process, albeit a double-edged benefit. On the one hand, employers are keen to hire racialised workers who might then bring acclaim to their establishment for being ‘diverse’, while at the same time demonstrating that stereotypes and racial biases have indeed penetrated hiring decisions ‘“Oh, you’re the Spanish girl.” As soon as you say that, you’re immediately the Spanish girl. You’re no longer (personal name), you’re the Spanish girl. I think it deters them from hiring other minorities when they already have one that’s like you said, the token minority’, said a Saskatchewan worker (SK Food Worker 12). Diversity is seen as a favourable business decision when desirable hiring racialised workers who fit, as economic value is assigned to the Other in a process of commodification (Evans Reference Evans2020) advanced by a white majority (Leong Reference Leong2013). Employers build up and maintain this aesthetic image in what bell hooks (1992) describes as the commodification of otherness by dictating how racialised workers should look and act. Tokenism provided an advantage that some racialised workers struggled to accept.

The only advantage you have is tokenism because it can be an advantage that you have a higher chance of getting hired at a place that doesn’t have visible minorities working there because they want to hire someone to be their token face. That can happen sometimes. I think that’s the only advantage we have. The disadvantage is the prejudice. People don’t wanna hire you because you’re a visible minority. People may not want you around certain guests that come in. (SK Food Worker 9)

Such conclusions of tokenism or advantage cannot be generalised to include Indigenous workers.

Indigenous labour: Overlooked and excluded

Governments have historically used paternalistic and coercive measures to mobilise Indigenous labour into particular sectors of employment through a process Laliberte and Satzewich (Reference Laliberte and Satzewich1998) describe as ‘Native proletarianisation’. Racism and human capital factors continue to perpetuate labour market discrimination and the marginalisation of Indigenous peoples (Bleakney et al Reference Bleakney, Khanam and Kumar2024; Howard et al Reference Howard, Edge and Watt2012; Mills and Clarke Reference Mills and Clarke2009). Research also points to structural forms of discrimination in knowledge-based and skill-intensive organisations like post-secondary institutions, where marginalisation is in part facilitated by the exclusion of Indigenous knowledge systems and worldviews through colonial hegemonic philosophical systems (Bastien et al Reference Bastien, Coraiola and Foster2023). These outcomes cannot be disentangled from colonial political-economic relations that define the Canadian state (Anderson Reference Anderson1997; Bourgeault Reference Bourgeault1983; Satzewich and Wotherspoon Reference Satzewich and Wotherspoon2000). Available policy and academic literature, however, focuses on determinants of labour market participation – from housing and health to education (Wannell and Currie Reference Wannell and Currie2016). What is not accounted for in these analyses are biases that might refuse Indigenous people access to employment even when their human capital criteria are met and possess equal standing with non-Indigenous applicants.

Anti-Indigenous discrimination was a centrepiece of our interviews, which is informed by Cannon and Sunseri’s (Reference Cannon and Sunseri2011, 234) claim that ‘structural racism sustains “the toxic gulf” between Aboriginal and settler communities’. Participants largely believed that Indigenous job seekers were treated differently by prospective employers (SK = 75%, ON = 66%) and that Indigenous candidates experience discrimination during hiring. Some interviewees, however, were simply unaware of special treatment or recognition either way. Workers commented broadly on the visual absence of Indigenous peoples in the industry as a whole, which is consistent with available labour market data (Anderson Reference Anderson2019). Some of this is attributable to the fact that not all Indigenous peoples are easily discernible as ‘racialised’ by other workers (Anderson Reference Anderson2019). And while Indigenous workers were not seen by all as being treated any differently than other racialised groups, biases were certainly present.

A lot of people that I have worked with… Literally a lot of people, minus Indigenous people, no matter their race, they are racist towards Aboriginal people, I’ve noticed. And I know that people sometimes, like an Aboriginal couple will come in, and a girl will be like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to serve them’, or ‘I feel like they’re not going to tip me’ … These racist stereotypes that they would form about Indigenous people would come from instances that we’ve had with Caucasian people, you know? (SK Food Worker 13)

Some participants concurred that racism plays a factor in why they do not see many Indigenous people working in the industry, even without having witnessed or experienced this kind of discrimination. Attributes like drug and alcohol addiction generate stereotypes that are not easily overcome, confirming that historical ‘facts’ presented about Indigenous peoples are both inaccurate and degrading (Reading Reference Reading2014). ‘Indigenous people’, said a food service worker, ‘are definitely given an unfair first impression a lot of the time … Actually in school, we are learning about intergenerational trauma and how that has really affected them and people don’t understand that necessarily and they will be really quick to judge and push them away and say no’ (SK Food Worker 6).

Indigenous people, one manager answered, were stigmatised by stereotypes that characterise them as prone to criminal behaviour and substance use in major urban centres. Such observations can then lead to more entrenched biases against a particular community (Wall Reference Wall2018), which is attributable to ‘relations of inclusion and exclusion’ tethered to holders of what might be deemed to be appropriate (or inappropriate) forms of cultural capital (Swartz Reference Swartz2013). Others maintained that they are indifferent to Indigeneity when reviewing resumes. Racism was, however, recognised as a reality in their respective communities. A Toronto-based food service business owner believed that the perception of Indigenous people suffering from addictions and social problems was enough for them to make a conscious decision to never hire Indigenous applicants. ‘They come from wherever it is they come and there’s nothing but crime’ (ON Hiring Manager 3). As Brewster and Nowak (Reference Brewster and Nowak2019, 160) write in their study of anti-Black racism in the food service industry, the prejudiced person rationalises or excuses their biases as the ‘outcome of anything but race (e.g., market forces, crime, work ethic, individual choices, culture)’. These biases also existed among frontline workers, and it speaks to the prevalence of racism as a whole in Western Canada (Kiprop Reference Kiprop2017). ‘The prairies, they’re a hot bed for anti-Indigenous racism’, a Saskatchewan-based manager reflected (SK Manager 9), pointing to the general acceptance of negative stereotypes haunting Indigenous peoples in the region.

Frontline workers who identified as Indigenous spoke about strategies deployed to cope with these attitudes. As a food service worker commented, ‘I try to turn a blind eye at it, and I know that’s not necessarily the right thing to do because it’s alive and well and what am I going to teach my daughter when she grows up?’ (SK Food Worker 28) Another Indigenous worker spoke of the need to endure: ‘there’s always one dick and it doesn’t matter if it’s the racism or whatever it is, there’s always something with some individual, and you have to find a way to work with them’ (SK Food Worker 24). Indigenous food service workers who fit, in this regard, are the ones who develop coping mechanisms to survive discrimination in the workplace, or who successfully disguise their Indigeneity.

The foreign worker (dis)advantage?

Foreign-born workers – temporary and permanent – play an important role in Canada’s service sector. The country’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) was even adjusted in the early 2000s to accommodate a shortage of low-wage food service labour in oil-extractive regions (Stevens Reference Stevens2022). Special migrant streams similarly exist at the provincial level to facilitate the production of workers destined for jobs in the industry. Demand for foreign workers even persisted throughout the pandemic, when unemployment reached double digits (Employment and Social Development Canada 2022). Labour market data reveal that the employment of newcomers in food services and accommodations differs across provinces, but also that immigrants are an important source of workers for this industry by measure of their contribution as a percentage of the food service labour force (Labour Force Survey 2022; Stevens Reference Stevens2022). Immigrants and migrant workers alike have certainly become fixtures of this industry in helping to fill short and long-term labour market shortages and even constitute a pillar of the country’s economic development strategy. But are newcomers uniformly welcomed by food service employers?

The reasoning for rejecting newcomer applicants takes several forms. Outcomes, we argue, are conditioned by the type of food service establishment and the associated role (FOH and BOH) within the industry and therefore inconsistent. Some employers assume that newcomers require additional time and training and thus forgo the opportunity to hire applicants they perceive to be non-Canadian due to their race or ethnicity (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2004). A frontline food worker in Ontario commented on this intersectional vector of labour market exclusion as follows:

Depending on the owner, obviously, but definitely there’s also other cases where there’s disadvantages, they don’t want to go through that training period with new immigrants and things like that, so it’s very dependent on who owns that business and who takes care of that store. (ON Food Worker 13)

Interview respondents indicate that the perception of cultural differences manifests as the understanding that newcomers struggle with acclimatising themselves to work in Canadian restaurants. ‘Some international workers, they come from different backgrounds, cultures, they have very little communication with other Canadian workers’ (ON Food Worker 14). Language and communication barriers – real and perceived – were recognised by managers and frontline food service workers as the principal reason why newcomers might struggle to secure employment in this industry. Disadvantages, where they exist, are generated by a notion that resumes and other employment-related documents could be falsified by newcomers – or what Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2019) describes as an expression of cultural racism, where discrimination is justified due to cultural differences or behaviours. This is tethered to the construction of fit.

Attitudes about newcomers are complex. In one establishment, managers were said to harbour biases against foreign labour, but, at the same time, the company would sponsor migrants from other countries and help them secure visas to extend their stay in Saskatchewan. On the other hand, English language competency was cited as a source of bias against immigrant workers. I think a lot of assumptions are made about newcomers about ‘is English their first language? What country did they come from? What were the standards like in their country of origin?’ (ON Food Worker 33) Some countries of origins and ethnicity were assigned value based on their perceived ‘work ethic’, thus constructing a migrant division of labour in the food service industry (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Lin and Neuberg2018). These workers possessed the required fit despite an employer’s apprehension about hiring newcomers.

I think that there’s you know, you can categorise people by race or however you want to do that, but I think that overall, it tends to be pretty positive…. (We) had a couple of very strong cooks that had a Filipino background that come from the Philippines that had been sponsored over by families, were incredibly great people and were incredibly hard workers and we went to them and said you know do you got any brothers, sisters, friends, relatives, uncles, and it just really opened up a door to lots of great workers. (SK Manager 1)

Frontline interview participants suggested that newcomers have an advantage when seeking employment in restaurants that align with their ethnicity and country of origin (i.e. an Indian newcomer working in an Indian restaurant). Interviewees further indicated that racialised managers were more likely to hire racialised workers of the same heritage, which implicitly provides an opportunity for this demographic (ON Food Worker 29). Foreign workers, however, are not necessarily treated well by employers who share their ethnic, cultural, or national origins – contrary to these workers’ expectations (Connelly Reference Connelly2023). There was also recognition that newcomers may possess skills and credentials that are overlooked or not valued by Canadian employers. Workers end up with precarious jobs in food service or retail, as a consequence.

Conclusion

Merit and hard-skill credentials, we find, are only part of what constitutes successful food service workers. Our interviews suggest that employers and frontline workers alike construct a notion of ‘fit’ that might advantage or exclude applicants based on racialised or gendered biases of what constitute aesthetically pleasing and hard-working employees. Stereotypes are hardly uniform (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Lin and Neuberg2018), however, and may create opportunities for some and serious disadvantages for others despite the prevalence of comparable human capital attributes. Applicants and existing employment might then be streamed into particular ‘balkanised’ segments of the food service industry (i.e., BOH, lounge, etc.) premised on what is recognised as socially determined aspects of fit (Bauder Reference Bauder2001; Peck Reference Peck, Stephen Ackroyd and Fleetwood2000).

For a nominally low-skilled occupation, employers put greater emphasis on soft skills and aptitudes that are required to succeed in the industry – or even to secure entry-level employment. Frontline workers share these attitudes in some instances, while resisting or criticising such beliefs at other junctures. What our interview findings suggest, however, is that fit exemplifies an ideal type composed of racial, gendered, and status-oriented features necessary to advance the interests of businesses that depend on precarious labour. Workers must be capable and willing to endure precarity as a soft skill attribute (Williams and Connell Reference Williams and Connell2010). And where employers are quick to confirm their willingness to hiring anyone regardless of ethnicity and gender, labour market outcomes tell another story, as does the catalogue of callback audit studies (Riach and Rich Reference Riach and Rich2002). We find that fit can be used to stream applicants into roles that align with preconceived gendered and racialised biases. In some instances vulnerable populations are advantaged with employment opportunities; in other cases, racialised workers find themselves on the margins of the labour market and compartmentalised into FOH or BOH ghettos due to the functionality of stereotypes (Fiske et al Reference Fiske, Lin and Neuberg2018). Indeed, the construction of ‘fit’ represents the vector of an intersectional space where gender, race, status, and ethnicity construct an ideal food service candidate in what is defined as precarious work.

Our analysis further suggests that Indigenous peoples are acutely impacted by this notion of fit in Canada. Although immigrants and migrants might engender a spectrum of qualities and credentials that appeal to employers who are seeking strong employees premised on their affability and work ethic, responses specific to Indigenous workers indicate that stereotypes are almost exclusively negative, or at best neutral. This ‘neutrality’ is premised on the notable invisibility of Indigenous food service workers within the sector. And while studies of food services speak to the immaturity of the industry’s HR practices (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, McAdams, Gibbs and D’Angelo2022), this paradigm fails to account for the structural conditions under which racism and discrimination are produced and reproduced within the labour market – or within the ranks of employers specifically. Unconscious bias training then falls short of addressing the fundamental problems embedded deep within a particular socio-economic context (Asare Reference Asare2019).

Equally significant is the ‘colour blind’ attitude held by some employers, who insist that they hire solely based on the qualities of the candidate’s experience. Fit, meanwhile, is widely held as a social construct informed by the intersectionality of race, status, ethnicity, and gender (Collins Reference Collins2019). Change, scholars argue, requires a focused anti-racist programming, not an allegiance to diversity or general anti-discrimination campaigns (Gebhard et al Reference Gebhard, Novotna, Carter and Oba2022). For these reasons, Kundnani (Reference Kundnani2023) reminds us, liberal anti-discrimination efforts necessarily reach an impasse. Nor can labour market advancement be reduced to the achievement of credentials and other resume criteria established by employers if the very lens through which resumes are examined is determined by other considerations. ‘Unconscious bias’ training and initiatives fall short of affecting meaningful change in this regard if the broader system goes unexamined (Asare Reference Asare2019).

Our analysis suggests that the constructed notion of fit functions as a gatekeeper that provides opportunity for some, but exclusion for others. Labour markets, segmentation theory concludes, are indeed defined by an institutional and social terrain that streams workers into a dual system even within particular (low-wage) industries. For marginalised populations, like Canada’s Indigenous people, the hope that education and experience might lift individuals out of poverty and underemployment is betrayed by culturally-defined notions of fit that are difficult for some to disguise.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank research assistants Jaya Mallu, Angele Poirier, and Siham Hagi for contribution to the interview, transcription, and coding phase of the research.

Funding statement

This projected was supported with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council in Canada.

Andrew Stevens, PhD, is an Associate Professor in Hill and Levene Schools of Business at the University of Regina. His research focuses on migrant labour policy, “just transition” and the political economy of the fossil fuel economy, the sociology of work, and collective action.

Catherine E. Connelly, PhD, is the Distinguished Business Research Professor of Organizational Behaviour at the DeGroote School of Business at McMaster University. Her interests include contingent work (e.g., temporary foreign workers), workers with disabilities, middle managers, and knowledge hiding in organisations.